Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Drama Classics

- Sprache: Englisch

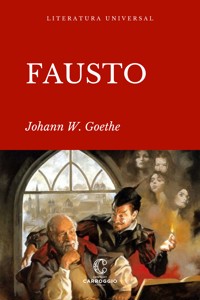

Drama Classics: The World's Great Plays at a Great Little Price A fresh, performable version by John Clifford of Goethe's 'unstageable' masterpiece. God and Mephistopheles vie for the mortal soul of Dr Faust. Signing a pact with the nihilistic spirit, Faust is privy to knowledge unbound and sensual delights of which most men can only dream. But before long, the Doctor comes to realise that you should always be very careful what you wish for. Goethe began working on Faust in about 1772-5. He published a first fragment of it in 1790, then the whole of Part One in 1808. He saw the first performance of Part One in Brunswick in 1829, and was still making minor revisions to Part Two shortly before his death in March 1832. This two-part English version by John Clifford, in the Nick Hern Books Drama Classics series, was first performed at the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh, in February 2006.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 173

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DRAMA CLASSICS

FAUST

Parts One and Two

by

Goethe

translated and introduced by John Clifford

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

Further Reading

Characters

Faust Part One

Faust Part Two

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Introduction

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)

1749

Born in Frankfurt as the eldest son of Johann Caspar Goethe, a lawyer and Imperial Councillor, and Katharina Elisabeth. In later life he was to attribute to his father his sense of the seriousness of living; and to his mother his creative and artistic gifts.

1765

Sent away to Leipzig to study law, where he meets the influential scholar and critic Johann Christoph Gottsched, who argued that seventeenth-century French theatre should be the model for German theatre: plays should be written in alexandrines, follow a classical structure, and observe the proprieties.

1768

Falls seriously ill and returns to Frankfurt. The Faust play is performed in Frankfurt by travelling players.

1770

Resumes his studies in Strassburg, where he encounters the critic Johann Gottfried Herder, a fierce exponent of the need to explore and celebrate the German in theatre and literature. Herder also introduces Goethe to Shakespeare. Goethe allies himself to other young writers in the birth of the Romantic movement: the so-called Sturm und Drang (‘Storm and Stress’). He also falls passionately in love with Frederike Brion. The Faust play is performed in Strassburg by travelling players.

1771

Returns to Frankfurt where he practises, rather lacklustrely, as a lawyer.

Susanna Brandt, a servant girl accused and then condemned to death for the killing of her illegitimate child, is publicly beheaded. Members of Goethe’s family are professionally involved in the case. He writes the first version of his play, Götz von Berlichingen, in which he takes a German subject, disregards the unities, writes in prose, and flouts all rules of decorum, giving his hero one of the most famous lines in German literature as he invites his opponent to ‘mich im Arsch lecken’ (‘lick my arse’).

?1772-5

Begins writing Faust.

1774

Götz von Berlichingen premieres in Berlin. Goethe’s epistolary novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther, creates a sensation, and establishes him as a major writer.

1775

Moves to Weimar at the invitation of its prince, and becomes a member of its government. Among the papers in his luggage is original Faust material which he reads aloud and circulates among literary circles in Weimar. A member of this circle, Fräulein von Göchhausen, makes a copy of this material, which will disappear from view after Goethe destroys his manuscript and will only become known when it is discovered by chance in 1887 and published under the title Urfaust. Begins to devote himself to ministerial duties. Develops an interest in the natural sciences.

1786-8

Travels in Italy.

1787

Publication of two plays: the final (iambic) version of Iphigenia in Tauris, and the historical epic, Egmont.

1788

Resumes work on Faust. Returns to Weimar and begins a relationship with Christiane Vulpius, whom he marries in 1816.

1790

Publication of Faust. A Fragment, and of the play, Torquato Tasso.

1794

Beginning of friendship between Goethe and the playwright Schiller. Over eleven years, they exchange over 1000 letters, a correspondence which is crucial to the artistic development of both writers.

1797

Schiller encourages Goethe to resume work on Faust. He decides to divide the work into two parts. Writes the dedication and the preludes.

1805

Death of Schiller.

1808

Publication of Faust, the First Part of the Tragedy.

1816

Death of Christiane Vulpius. Early version of fragments of Part Two of Faust. Goethe begins to be fascinated by large-scale engineering works, and by the prospect of a Suez Canal.

1825-6

Continues work on Part Two.

1827

Act Three of Part Two published as Helena, an intermezzo for Faust in Goethe’s last edition of his Collected Works.

1829

First performance of Faust Part One, in Brunswick.

1831

The whole work completed on 22 July. Goethe seals the manuscript.

1832

January: Manuscript opened. Possibly a few minor revisions. Reads some of the manuscript to friends.

March 22: Dies.

December: posthumous publication of Faust: the Second Part of the Tragedy.

Doctor Faust

The story goes that there really was a Doctor Faust.

His name was Johann, or possibly Georg, and he was active in the German lands in the early 1500s. It was told of him that he could perform magic, real magic of the forbidden and powerful kind, that he could summon Helen of Troy, the most beautiful woman ever known in the world, that he had a familiar in the shape of a terrifying black dog. That he had made a pact with the Devil: that to obtain his magical powers he had bargained away his soul. So the mysterious circumstances of his fearful death, round about 1540, were the result of the Devil coming to claim the soul that was his due and carrying it off to hell.

Something about this story captured the popular imagination; in alliance with the mysterious new technology of printing, it began to be circulated in cheaply printed, anonymously written and illustrated storybooks, one of which was translated into English in the 1590s. It fell into the hands of the heretic dramatist Christopher Marlowe, whose Tragicall Historie of Doctor Faustus was the hit of the London stage in the years following its first recorded performance in 1594. From there, it passed into the repertoire of the English travelling players who toured the German lands in the 1600s, was translated back into German and regularly performed by the first German actors and puppeteers as the German theatre began to emerge from the ravages of the Thirty Years’ War.

And it was probably either as a puppet show or as a travelling melodrama that Goethe first encountered the story as a boy. Or perhaps it came as a printed scenario included with the puppet theatre his grandmother gave him as a present. Perhaps he manipulated the puppet Faust, the puppet Helen that Faust summoned from the dead, and the puppet Mephistopheles dragging his creature down to hell. However it happened, it was the beginning of an obsession that possessed Goethe at frequent intervals in the sixty long years of his creative life.

When Goethe was a boy, he lived in the pre-industrial lands of the Holy Roman Empire; when he was a young man, the absolute monarch of France was dragged onto the street like a common criminal and guillotined; when he was old, Germany was becoming a modern industrialised state. To say he lived in a period of the profoundest social and technological change is something of an understatement; and it is no coincidence that the story which so fascinated him was itself the product of other profound historical changes: of the painful and protracted death throes of the medieval world.

And so of course it is equally no coincidence that the story should so fascinate us now, in the death throes of the modern world: as we contemplate with shock and with awe the powers of the computer, the atomic age and the emerging biotechnologies, and as we wonder, with deep terror in our hearts, what price we will have to pay for them.

Goethe and Faust

As we try to come to grips with this amazing work, it is important to remember that its creation occupied Goethe during the whole of his amazingly long creative life. So the whole lengthy, and immensely fraught, process of creation encompasses the profoundest changes in Goethe’s personal circumstances, his views on art, outlook on life and political beliefs, as well as huge changes in the social, political and physical landscape of Europe as a whole.

He didn’t work on the project consistently, or in any kind of normal order, but in fits and starts, frequently abandoning the work altogether when the emotional and technical problems it caused him became simply too great for him to tackle at the time. And yet Faust never wholly left him alone. He was compelled to return to it again and again, rewriting, revising, creating new material until, only a few months before his death, it was finally completed. He rarely took the time or trouble to reconcile the new material with the old; as a result, the whole work rather resembles the archaeological site of one of those ancient cities in which remains from entirely different eras lie side by side, sometimes incongruously, cheek by jowl with each other.

To try to make sense of it all, it is helpful to remember one of Goethe’s descriptions of his work as ‘fragments of a great confession’ (in his autobiography, Poetry and Truth, Book VII). Perhaps it also helps to see the work as some kind of gigantic self-portrait that somehow encompasses the whole of a human being in all his multiplicity, nobility, superficiality, vanity, humility, utter complexity and contrariness. Certainly there is a kind of sprawling human generosity to it that I love, cherish, and profoundly admire.

In a letter he wrote on 20 July 1831, eight months before his death, Goethe said that he had carried the material for Part Two in his imagination for years and years ‘as an inner fable’ (‘inneres Märchen’). Märchen is a word I would define as ‘fairy tale’ in the sense that Bruno Bettelheim understands it in his Uses of Enchantment: a story that expresses a profound truth, or truths, about the world that cannot be expressed in any other way; a story that explores truth, or truths in particular that relate to the collective unconscious of a people or a culture; a story that possesses something of the simplicity, directness, and utterly unfathomable complexity of a kind of collective dream. This, too, helps us come to grips with the work; it certainly describes something of the quality I have tried to retain in my adaptation of it.

As to the form this collective dream, or fable, took, the key to it can be found in the correspondence between Goethe and Schiller. It was Schiller who encouraged Goethe to resume work on Faust at a time when he seems to have decisively abandoned it; and their discussion on aesthetics seems to have had a decisive effect on Goethe’s approach to the work. This discussion (in 1797) is summarised by David Luke in the introduction to his translation of Part Two:

Drama as such is characterised by logical consistency and economy, the precipitation of the action towards the dénouement, the subordination of the parts to a single purpose that the end will bring to fulfilment. In the epic style, on the other hand, ‘sensuous breadth’ is of the essence: certain discursive lingering over pleasing detail and episode for its own sake, a tendency of the parts to pursue their own enjoyable autonomy rather than remain functions of a tightly controlled, end-directed whole.

(p. xiv)

Translate this into artistic action, and you get Schiller’s Mary Stuart on the one hand, and Goethe’s Faust on the other. So the aspects of Faust that most trouble me as a playwright – the meanderings, inconsistencies, abrupt discontinuities, contradictions, apparent utter lack of dramatic direction – do not trouble Goethe at all.

We are confronted with the profound paradox of a work written in dialogue form by a practising playwright that is essentially not a play at all. A play written by a writer with the profoundest practical knowledge of the theatre, a man who, besides writing plays, acted in them, enjoyed performing his work to friends, ran both an amateur and a professional theatre for many years, reflected deeply on theatrical processes, wrote an eminently sensible set of precepts for actors, and yet who came to the final conclusion that his most personal and important work had to free itself from the constraints of theatrical form.

To be sure, he never made any serious attempt to stage it, though he was certainly in a position to do so had he truly wished. Instead, it seemed utterly reasonable to publish Faust. A Fragment in 1790, and Helena, an intermezzo for Faust in 1827 as completely self-sufficient works. Needless to say, as a practising playwright, I find this insouciance utterly maddening. And I am fascinated and appalled by Goethe’s sealing of the manuscript of Part Two so that no one could read it, still less perform it, until after his death. To deny a work its exposure to its audience is, in my terms, to condemn it to death. But for Goethe, this must have been something utterly liberating: something that enabled him to give his conception the form it demanded without any concern or anxiety about the response of his readers or audience. He does seem to have been a little concerned about the controversy his ending (with the Devil discovering love with an Angel) might have aroused; but the overriding impression I am left with is that he needed to free himself completely of any anxiety or consideration for what his readers and his audience may have felt about the work. The work needed to take the form it needed to take. That and no more.

What Happens in Goethe’s Faust

PART ONE

Dedication Goethe reflects on past friends, and on how this long-neglected and now resumed work, belongs to a past he thought he had forgotten long ago.

Prelude on the Stage Poet, Director and Comedian reflect on their different perspectives on the current theatre scene.

Prelude in Heaven God and the Devil make a bet on the future of Faust. The Devil bets he can destroy him.

Night Faust is disillusioned with all conventional knowledge and summons up the Earth Spirit by magic. But he cannot bear the sight of it. Wagner, a pedant, interrupts him. Faust, in despair, is about to poison himself but is interrupted by a chorus of Angels who announce the arrival of Easter.

Outside the Town Wall A whole group of different people leave the town walls to set out on country walks. Faust is out walking with Wagner. He reflects on the significance of spring. Villagers are dancing: one of them remembers with gratitude how they were helped by Faust and his father in a time of plague. Faust seeks out a solitary spot: his memories of the falsity of his father’s profession torment him. In the distance they see a black dog: they discuss whether its appearance is natural or unnatural.

Faust’s Study (I) Faust has brought the dog into his study and begins to translate St John’s Gospel. Convinced there is something uncanny about the creature, he conjures it to appear in its true form. It appears as Mephistopheles. He defines himself as a spirit of destruction. He brings spirits to entertain Faust, who falls asleep. Then he summons mice and rats to gnaw away at the pentagram Faust has written on the floor that prevents him leaving. Faust awakes to find the Devil gone.

Faust’s Study (II) The Devil returns. Faust admits he longs for death: and he curses faith and hope. They make a pact, whose terms are not made altogether explicit. Faust withdraws to prepare himself for his new life. A new student appears, and the Devil disguises himself as Faust to give him misleading advice. The student goes, Faust reappears, and they set off on their journey together.

Auerbach’s Tavern in Leipzig Their first port of call is a student tavern. The Devil plays practical jokes on the merry-makers.

A Witch’s Kitchen The Devil takes Faust here to give him a spell to make him young.

A Street Faust sees Gretchen, falls in love with her, and commands the Devil to attain her for him.

Evening – in Gretchen’s Room After she has left, the Devil brings Faust into the room. He is entranced by the innocence of it. The Devil leaves a case of jewels as a present, and they leave. Gretchen discovers the jewels and tries them on.

A Promenade The Devil is furious: a priest has ended up in possession of the jewels. Faust commands him to obtain another present.

The Neighbour’s House Gretchen has come through to see her friend Martha with a second case of jewels that has been left her. The Devil appears, and pretends to know about the circumstances of Martha’s soldier husband’s death. He promises to bring back a companion who can testify to the details.

A Street The Devil persuades a reluctant Faust to sign a document swearing Martha’s husband’s body is buried in Padua, where he was a mercenary.

A Garden Martha and Mephistopheles, Faust and Gretchen court each other.

A Summerhouse Faust and Gretchen declare their love for each other.

A Forest Cavern Faust has withdrawn to the natural world, where the Devil finds him and takes him back into the fray.

Gretchen’s Room Gretchen sits and spins and sings a sad song of her love for Faust.

Martha’s Garden Gretchen and Faust are reunited. Gretchen’s love for Faust, who she calls Heinrich, is so intense she is completely in his power.

At the Well Lieschen tells Gretchen of a girl they know who has become pregnant by a man who has deserted her. On her own, Gretchen confesses the same has happened to her.

By a Shrine inside the Town Wall Gretchen prays to the Virgin for forgiveness.

Night – the Street outside Gretchen’s Door Gretchen’s brother, Valentine, a soldier, bemoans the loss of Gretchen’s reputation. The Devil helps Faust knife him. The dying Valentine pronounces a terrible curse on his sister in the street in front of all her neighbours.

A Cathedral An Evil Spirit tells Gretchen she is doomed to go to hell. She faints.

Walpurgis Night Mephistopheles and Faust travel up the Harz mountains to a gathering of witches. They meet some on the way: Faust has a vision of Gretchen suffering.

A Walpurgis Night’s Dream An amateur show, loosely based on Shakespeare, in which Goethe pokes fun at certain literary figures in his day.

A Gloomy Day – Open Country Faust learns Gretchen is imprisoned for having killed her baby and is awaiting execution. He is furious with Mephistopheles over Gretchen’s suffering and decides to rescue her.

Night – in Open Country On their magic horses they ride past some witches doing something unspeakable to a corpse.

A Prison Faust tries and fails to rescue Gretchen from prison. Her sufferings have driven her mad and she will not come with him. The Devil says she is doomed; the Angels say she is saved; she is left calling out for ‘Heinrich’.

PART TWO: ACT ONE

Prologue – a Beautiful Landscape Ariel and other nature spirits help Faust rest, recover and forget his previous ordeals.

An Imperial Palace – the Throne Room Mephistopheles has inveigled himself into the Emperor’s suite by taking the place of his Fool. He promises to help the Emperor overcome his troubles. He invents paper money.

The Carnival Masque A seemingly endless parade of allegorical figures culminates in the Emperor almost being burnt alive.

A Pleasure Garden Faust is now in the Emperor’s court. The success of paper money means he and Mephistopheles are in the Emperor’s favour.

A Dark Gallery Faust has promised to make Helen appear to the court. Mephistopheles explains that to do that he must go underground and find the Mothers. Faust sets off on the adventure.

Brightly Lit Halls Mephistopheles harassed by officials eager for the show to start and by girls who want love potions.

The Great Hall Paris and Helen appear. Faust falls in love with Helen, tries to touch her, and falls unconscious.

PART TWO: ACT TWO

A High-Vaulted Narrow Gothic Room Back in Faust’s old study, Mephistopheles puts on Faust’s old professor’s gown and learns from an aged Famulus that Wagner is involved in deep scientific and alchemical studies. The Devil asks to be brought to him. He is visited by the young student of Part One, now a brash and arrogant graduate.

A Laboratory Wagner is creating an artificial human, the Homunculus. He succeeds in bringing him to life. The Devil asks for his help in curing Faust. The Homunculus recommends a trip down to the Classical Walpurgis Night, in ancient Greece. The three of them set off, leaving Wagner behind.

Classical Walpurgis Night Mephistopheles, the Homunculus, and Faust split up and each have a series of fantastical encounters. Eventually, Mephistopheles encounters the Phorcyads, and becomes one of them. Faust encounters the Centaur Chiron, who helps him find a passage to the Underworld, where he will be prepared to see Helen. The Homunculus meets the sea God Nereus, and plunges into the infinite vastness of the ocean deep.

PART TWO: ACT THREE

In Front of the Palace of Menelaus in Sparta Helen and a Chorus of captive Trojan women have returned from the Trojan war. Helen has been told to return home and prepare for sacrifice. They are disturbed by the presence of Phorcyas (Mephistopheles) who they see as a hideously ugly woman at the gate of the palace. He/She tells them they are to be the sacrifice and persuades them to come to a nearby fortress where they will be rescued.

The Inner Courtyard of a Castle The rescuer turns out to be Faust in the shape of a medieval knight. His watchman, Lyncaeus, has failed to tell him of Helen’s arrival. Faust offers to have him killed for her sake. Helen refuses, and agrees to stay with Faust.

Arcadia