Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IVP Formatio

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

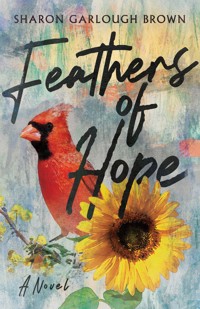

- Serie: Shades of Light Series

- Sprache: Englisch

"We fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen." (2 Corinthians 4:18) In a season of loss and change, Wren Crawford and her great-aunt, Katherine Rhodes, share the journey as companions in sorrow and hope. As Katherine prepares to retire as the director of the New Hope Retreat Center, she faces both personal and professional challenges—especially after the arrival of the board's candidate to replace her. Not only must she confront more unresolved grief from her past, but she's invited to embrace painful and unsettling insights about her own blind spots. How might disruption become a gift that opens the way to new growth?Wren's world is shifting and expanding as she presses forward in recovery from a period of deep depression. Still processing open questions around the death of her best friend, Casey, Wren stewards her grief by offering compassionate care to the residents of the nursing home where she now works. But the shedding of her old life is exhausting—especially as she doesn't yet see what new life will emerge. How might art continue to provide a pathway for deepening her awareness of God's presence with her?In this sequel to Shades of Light and Remember Me, fans of the Sensible Shoes series will not only be able to attend Katherine's final retreat sessions at New Hope but also encounter old and new friends along the way.Also available: Feathers of Hope Study Guide

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 551

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For — and with — my beloved son, who generously poured out his wisdom, insights, and creativity on every page of this book. David, you inspire me with your courage, kindness, and gentleness. I am so honored and proud to be your mom.

The LORD bless you and keep you; the LORD make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you; the LORD lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace.

Contents

1

When the cardinal landed at their bird feeder early that morning, its eyes bulging, its head stripped of red crest feathers, leaving it black and bald, Wren Crawford was sure the poor creature was either sick or wounded. She set her second cup of coffee on the kitchen table and watched him through the glass slider. If he didn’t drop dead on the patio now, she would likely find him in the yard later. She hoped she would find him before the neighbor’s cat did.

She checked the cupboard beneath the sink for spare gloves. She would get a garden trowel, too, in case she needed to carry him to the woods for a burial.

Just as she was picturing the scene, her great-aunt, Katherine Rhodes, sidled up beside her, wrapped in her terrycloth robe and holding a striped journal. She followed Wren’s gaze to the yard. “Molting season,” Kit said. “That guy lost all his feathers at once.”

Wren felt her shoulders relax. “So, he’s not sick?”

“No, he’s fine. Just not too handsome right now.” Kit’s gentle smile indicated she not only perceived where Wren’s racing thoughts had landed but understood how they’d arrived there. “Most birds molt gradually,” she said, “but every once in a while, you see one that’s experienced a more sudden, dramatic shedding of the old.”

After living under Kit’s roof for nine months, Wren had grown accustomed to her speaking in metaphor. But instead of offering any further insights, Kit patted her arm and said, “He’d make an interesting painting, don’t you think?”

Yes. Someday. When she had energy for creative work again. She grabbed her phone off the kitchen table and snapped a photo before the bird flew away.

Vincent would have painted him, she thought later that morning as she loaded her housekeeping cart with supplies from the nursing home storage room. The man who had painted peasant workers and starry nights, sunflowers and kingfishers, would have painted that molting bird with such tenderness, it would have made her weep.

Because he knew how molting felt.

She pushed her cart down the first of three resident hallways she was responsible for cleaning, noting the shadow boxes along the way. Fastened on the wall outside each door were miniature museums filled with curated items to remind staff and visitors of the lives the residents had enjoyed before the loss of occupations, hobbies, health, or loved ones.

As she dusted Mr. Kennedy’s box, with its slightly stained Titleist golf ball, a packet of heirloom tomato seeds, and a photo of him as a robust young man in a military uniform, she prayed for him. Molting was a good metaphor, not just for herself but also for the people she served. And not just for the residents but also for the people who loved them. The spouses. The children. The grandchildren. The friends. They were all shedding in different ways. Some more dramatically than others.

“Good morning, Mr. Kennedy,” Wren said as she placed her hands beneath the sanitizer dispenser on the wall.

He was seated in a faded armchair beside the bed, his thin hair not yet combed, a white towel tucked like a bib into his gray-checkered pajama top. At the sound of her voice, he glanced up from his breakfast tray, where he was trying unsuccessfully to spear a sausage with his fork. The tremor was bad this morning.

Leaning her head back, she scanned the hallway. No nurses or aides in sight. “How about if I help you with that?” She walked over to the tray table and guided the fork to his mouth. He took the bite and chewed slowly. “Is it good?”

He swallowed, then opened his mouth like a little bird. Gently, she loosened his grip on the fork, loaded it with another bite, and held it to his lips. He took it, chewed, and swallowed. Then he sputtered with a cough.

“Are you okay?”

He coughed again.

She reached for the plastic two-handled sippy cup on his tray. “This looks like apple juice. Is that all right? Or would you like me to get you some water?”

With a thin, weary rasp, he replied, “Juice is okay.”

She guided his fingers to each handle. “Got it?”

“Yep.” His tremor caused the juice to splatter onto his face as he maneuvered the spout to his lips. She waited for him to finish drinking, then helped him set the cup on the tray. Just as she was about to dab his chin and cheeks with a napkin, one of the nurses entered, carrying a small container of applesauce, a glass of water, and a plastic cup with pills. Greta eyed Wren but said nothing. “I’ve got your morning medications, Pete.”

Wren slipped out of her way.

“Whoops,” Greta said, “looks like you had a shower.” She wiped him off with a corner of his towel bib.

As Wren disinfected her hands again, she surveyed the small memento collection in the room: a golfing statue engraved with his name, a picture of Mr. Kennedy beaming beside his wife on a sailboat, and a few framed photos of his son and grandchildren, who lived in California. Mr. Kennedy said they came to visit sometimes, but he also said his wife came to visit sometimes, and she had died seven years ago.

Greta spooned out a bit of applesauce and placed a pill on top. “Okay, first one, Pete. Open the chute. A little wider. Got it? Good.” She watched him swallow. “You need water to wash it down?” When he did not reply, she put a hand to her hip. “Is that a ‘no, thank you’ or a ‘yes, please’?”

He swallowed again and said, “No, thank you.”

She loaded up another pill. “Okay, next one coming. You know the drill. Good job. One more, okay? Almost done.”

When Mr. Kennedy spluttered and coughed, Greta handed him a cup. “You’re scheduled for a bath today. We’ll get you smelling nice and fresh.”

He murmured something Wren couldn’t hear.

“You need help getting to the bathroom?” Greta asked.

“I’m okay,” he said.

“Don’t wait until I leave and then ring your call button. I’m here now. You sure you don’t need to go?”

“I’m sure.”

“Okay. Chelsea will be here soon to help bathe you and get you dressed.” She turned toward Wren. “You might want to wait to clean until they’re finished.”

“All right,” Wren said. After Greta left, she approached his chair. “Do you want me to turn on the Golf Channel for you, Mr. Kennedy? It’s Thursday. I bet there’s a tournament somewhere.”

He nodded. Wren picked up the remote control from his tray and turned on the television, which was already set to the right channel.

“You want to watch with me?” he asked, his voice not much louder than a whisper.

“I’d love to, but I’ve got more cleaning to do. Would it be okay if I join you after I’m done?”

He cleared his throat and paused, as if uncertain whether he could project loudly enough to be heard again. “Sure thing.”

Wren smiled at him. Sometimes speaking even two syllables was heroic. “I’ll be back after your bath to clean, okay?”

“Okay.”

She set the remote control down again, close enough for him to reach it. “Is there anything else you need right now?”

He stared at her. “My wallet.”

Wren tucked a strand of her dark hair behind her ear. She’d had this conversation with him many times. “Your wallet’s in a safe place. You don’t need it today.”

“You need a tip for cleaning my room.”

She patted his shoulder. “It’s okay, Mr. Kennedy. Everything’s already been taken care of.”

“I already paid you?”

“Yes.” That was the simplest answer. “Would you like to keep working on your breakfast?”

“Sure.” In the three months she had known him, she had never once heard him complain about his sausages or eggs getting cold.

“Okay, I’ll see you later.” From the doorway, she silently cheered him on as he tried to load his fork. He had probably once been as fiercely determined to sink a long putt. She straightened a few bottles on her cart and waited until he had successfully conveyed his food to his mouth before she proceeded to her next room, celebrating one inconspicuous, monumental victory.

“Wren, can you come help me with this?”

She looked up from the carpet, where she was kneeling to pick up staples that had fallen off a bulletin board the activities director was redesigning. Having removed the Uncle Sam, Liberty Bell, and fireworks pictures, Peyton, who was a few years younger than Wren and working her first job out of college, was now decorating for a tropical beach party.

Wren joined her at a table covered with cutouts of pineapples, palm trees, and surfboards.

“Hold these, will you?” Peyton handed her two streamer rolls, then started unrolling and twisting the red and yellow strands together. “I hope we get a good turnout this time,” she said. “I scheduled it for a Sunday afternoon, thinking we might get more grandkids that way.”

Wren nodded. Only a few kids had shown up for the Fourth of July barbecue. But more families might be in town mid-August. “Have you done this theme before?”

“Yeah, right after I started working here last summer. But most of these guys won’t remember. And we’ve got lots of new people.”

Wren flinched. Given how casually she’d said it, Peyton probably wasn’t thinking about the reasons for the high turnover. Becoming immune to death or decline seemed to be an occupational hazard at Willow Springs.

Peyton finished winding the streamers, taped off her end, and motioned for Wren to tear off her side. “Thanks,” she said as Wren handed it to her. “Want to help with the bulletin board, or are you still cleaning rooms?”

Wren set the rest of the crepe paper on the table. “I’m done with rooms. I’ve just got to vacuum the hallways.” Since it didn’t make sense to vacuum before Peyton finished decorating, she reached for the stack of pudgy letters. “What do you want it to say?”

“I sketched the whole thing there.” She gestured to a sheet of paper.

While Wren pinned letters for “Aloha Friends” and “So Happy to Sea You,” Peyton described her plans for themed decor, food, and crafts. Kayla, one of the certified nursing assistants, had grown up in Hawaii and was willing to demonstrate a hula dance. “People will love that,” Peyton said. “She can teach all of us some simple moves.” Wren wondered how Mr. Kennedy would feel, battling to control his arms and hands.

The elevator doors swished open, and she looked over her shoulder. Mrs. Whitlock’s daughter Teri, who rarely missed a day of visiting, removed a visitor badge from the basket, then rolled her shoulders and took a deep breath before she realized she’d been observed. When Wren waved to her, she put on a smile and glanced at the bulletin board. “You girls always make it look so festive in here.”

Peyton swished her long blonde ponytail and made a mock curtsy. “Thanks. I try.”

Wren faced the board again.

“So sorry to interrupt,” Kayla said as she strode into the lounge, “but there’s a bit of a mess to clean up in Miss Daisy’s bathroom.”

“I’ll be right there,” Wren said, and retrieved her cart from the hall.

2

Katherine Rhodes was revising notes for Saturday’s retreat when her cell phone buzzed on her office desk with a text from Wren: Hi, Kit! Staying late to watch golf with Mr. Kennedy. Go ahead and have dinner without me.

In that case, Kit thought, she might as well stay late too. She typed, Sounds good. Enjoy! Then she leaned back in her chair and stretched. With only a few weeks left in her tenure as the director of Kingsbury’s New Hope Retreat Center, plenty of work remained.

Nearly four months had passed since she submitted her resignation letter, and the board had planned to complete their candidate search by the end of July. But she could see August from her window, and they hadn’t found her replacement.

Or perhaps they had, and she didn’t know it yet. The search process had been far more confidential than she’d expected—which was, she frequently reminded herself, the board’s prerogative. Though she had provided them with names of people she considered gifted for the role, the job description the board subsequently developed indicated a desire to move in a different direction.

From her desk she withdrew the file folder labeled “Transition” and pulled out the single-page document she’d printed from the website. Her resignation had freed them to re-envision what they wanted and needed. And what they wanted was someone with strong leadership gifts and an entrepreneurial spirit, a digitally savvy marketer with fundraising experience. They wanted someone who could increase the donor base, oversee a building renovation project, develop an active social media presence, and expand New Hope’s outreach in West Michigan and beyond.

She had often seen it happen in ministry, how the search team would pursue someone with gifts that addressed perceived or actual deficits in the predecessor. She tried not to take it personally. In all her years of serving at New Hope, she had never pretended to be anything other than a spiritual director and retreat facilitator.

She considered the threadbare carpet in her office. The building was tired. So was she. Ever since she first discerned the need to let go and say yes to whatever next chapter might unfold, her weariness had deepened and accelerated. Though the board had granted her permission to lead a final Sacred Journey retreat after she retired, she had decided it was best to step away completely. Let the new leader have room to establish a presence and vision distinct from hers.

“Knock knock!” a familiar voice called from the doorway.

“Mara!” she exclaimed. Had she forgotten to write down a spiritual direction appointment? She skimmed her open calendar. Nothing listed for four o’clock. “Come on in. Welcome!” She tucked the job description back into her file folder and pushed herself up from her desk. She would need to quickly shift gears to be prayerfully present.

Mara embraced her with a bear hug, then set her beaded bag on the floor. She wore her usual bright colors—a turquoise tunic with orange bracelets and a matching necklace—and her ivory skin beneath her auburn hair showed a hint of sun along her nose and brow.

Kit was about to collect the Christ candle and a box of matches when Mara said, “Sorry to interrupt, but I was talking with Gayle about the catering details for your party, and when I saw your door was open, I thought I’d come say hi. Hope that’s okay.”

“Of course!” It was more than okay. A casual conversation would require far less mental and emotional energy than a spiritual direction session. “I was just thinking I’d make myself a cup of tea. Would you like one?”

“Sure! Ginger peach if you’ve got it.”

“I keep some here just for you.” From her shelf she retrieved two Vincent van Gogh mugs Wren had given her and dropped a teabag in each. “I’ll go boil water and be right back.”

“I’ll come with you,” Mara said. “Let me carry those.”

Together, they made their way down the hall to the kitchenette, Mara’s bangles clinking against the porcelain. “Guess it’s been a few months since I was here.” She gestured toward the walls. “I like what you’ve done with all the art. Is it all Van Gogh stuff?”

“Yes. Wren has done all the curating.” The corridor was lined with paintings of sowers and reapers, wheat fields, olive groves, and sunflowers in various stages of bloom and decay. If the new director didn’t want to keep the art gallery for prayer, he or she could remove all the prints and have the walls painted.

“What’s this one?” Mara pointed with her chin to a sketch of an elderly bald man bent forward in a chair, elbows clamped to his thighs, fingers clenched into fists and fastened to his face.

“Worn Out,” Kit said. She had meditated frequently on that one. She emptied stale water from the kettle and filled it again.

“Poor guy,” Mara said. “Don’t you just want to kiss him on the forehead and tell him to hang in there?”

Or pull up a chair next to him, Kit thought, and share the silence.

Mara set the mugs down and leaned against the sink. “Is Wren working here today?”

“No, she’s at the nursing home.”

“Is she working more hours there now? I haven’t talked to her lately.”

“No, her hours are the same. But she spends a lot of extra time there, keeping the residents company.”

“Good for her,” Mara said. “I couldn’t do it. Way too sad. Strange that she can, though, with her depression and everything.” As soon as she said the words, she grimaced. “Sorry, that came out wrong. What I mean is, I’m surprised it doesn’t drag her down, being around sickness and death all the time.”

Kit had made the same observation herself, how, rather than being weighed down by the sadness in a place like that, Wren seemed comforted by it. Enlarged by it, even. Companions in sorrow, she often said. A whole community of them.

“I’m glad she’s doing okay,” Mara went on. “But I keep telling her that her gifts are wasted scrubbing toilets and mopping floors. She needs to do art therapy somewhere. Not with battered women and kids like she did before. I get how that was too much for her. But someplace where she can paint and draw with people. If I had money in the budget at Crossroads, I’d hire her in a heartbeat to work with our people. They could use some art to brighten their world.”

She sounded like Jamie, who often expressed similar concerns and longings for her daughter. Wren might have an easier time hearing it from Mara, though, than from her mom.

When the water finished boiling, Kit held up the mugs. “Starry Night or Irises?”

“Starry Night.”

She poured Mara’s cup first, then handed her a spoon. “I’ll let you decide how strong you want it.”

“Ah, just leave it in today. The stronger, the better.”

“That kind of day, huh?”

“That kind of season,” Mara said. “I’ll spare you the details until we meet for spiritual direction. For now, I want to talk about your party.”

Kit stirred her tea. “I’m afraid that party’s getting a bit unwieldy.” She squeezed out the bag and tossed it into a trashcan that needed to be emptied. She would have to remind Wren to keep an eye on that sort of thing. The new director might not be as lenient.

“Wren told me you’d be happier retiring without any fuss. Not gonna happen, Katherine. You’re being celebrated, like it or not. You spend all these years, helping other people know how much God loves and treasures them, you’re not leaving here without us reminding you. Orders from Jesus. You can talk to your own spiritual director about your resistance.”

Kit laughed. “I’ve trained you too well, Mara.”

“Ha! At sixty, I’m glad I’ve learned a few things along the way.” She linked her arm with Kit’s. “Let’s go talk about this shindig, shall we?”

She didn’t have any special requests for the menu, Kit said as they chatted in her office, but she hadn’t expected the affair to include a full dinner. She had assumed they would have light appetizers and cake.

“We’re not just gonna do chips and dip from Costco, Katherine. If you’ve got a problem with that, talk to your daughter. I’m under direct orders from her too.”

“Ah,” Kit said, throwing up a hand in mock surrender, “it’s done, then. Who am I to argue with Jesus or Sarah?”

Mara grinned. “Now we’re trackin’.”

Kit took a slow sip of tea. New Hope didn’t have money in the budget for a party like this. If Sarah had insisted on a sit-down meal, then she and Zach were likely footing the bill. Just receive it, Mom, Sarah would say. And celebrate the love and appreciation the gift conveyed.

Mara scanned the office, her expression wistful. “I can’t believe you’re retiring. We’re gonna miss you around here.”

“I’m not going far,” Kit said.

“You better not. I’ll hunt you down, show up on your doorstep.”

“And I’ll welcome you in.”

Mara pressed her hand to her heart. “You always have. And I’ll always be grateful you hunted me down when I was ready to ditch my first retreat.” She patted the couch cushion. “I’ve logged an awful lot of miles here with you since then. And I’m sorry I won’t be able to come to your last retreat. I wanted to, but I’ve been leading Saturday morning training sessions for volunteers, and I can’t turn that over to anyone else right now.”

“No worries at all,” Kit said. “You’re doing important kingdom work.” She couldn’t remember how long Mara had served as one of the directors at the homeless shelter, but the job made perfect use of her passions, gifts, and personal experience of having once been a resident there with her oldest son. Hers was one of many beautiful stories of redemption Kit had been privileged to watch unfold.

She wrapped both hands around her mug.

That part of her work wasn’t over, she told herself. She could continue meeting with any directees who still desired her companionship as they traveled deeper into God’s love and grace—if the Lord continued to empower her for that work. During the past few months, she had been acutely aware of his strength being perfected in her weakness. Which was its own gift of grace.

“Keep reminding me about the kingdom work part,” Mara said, “because I’ll tell you what. Maybe I’m getting cranky in my old age, but I just don’t have a whole lot of patience these days for people who refuse to grow.”

“Sounds like there’s a story here,” Kit said.

“Have you got a few more minutes?”

“Sure.”

Mara set her mug on the coffee table. “God knows I’m not pointing a finger at people who say stupid things. I’m the queen of inserting my foot into my mouth. But when you say something stupid that hurts somebody else and then you get angry and defensive when they tell you it hurt . . . when you double-down and blame them for being overly sensitive instead of being open to the possibility that you’re blind or ignorant . . .” She pushed her lips to the side and puffed out a long breath, blowing her bangs back. “I know all about that MO, put up with it for way too long in my marriage. So I guess my radar is ultra tuned in when I hear somebody do that to someone else. And it’s been happening a lot at Crossroads lately. I’m tired of it. So I’ve been calling it out and ticking off some of the volunteers. At this rate, we may not have many people left to help.”

“I’m so sorry,” Kit said, setting her mug down as well. “Is there a certain theme or issue that’s surfacing, or is it short fuses in general?”

Mara rested her sandaled feet against the rim of the table. “Seems like no matter where you turn these days, people are ready to explode—the whole ‘I’m right and you’re evil’ mentality—but I’m talking about attitudes and comments some of the White volunteers have made about some of the Black residents and volunteers. Not just about, but to.”

Kit felt her shoulders tighten. She hadn’t expected this kind of conversation and didn’t feel at all prepared to navigate it well. Help.

“All the blatant racism stuff is easy to call out and name,” Mara continued. “It’s the more subtle forms we’ve been trying to educate our staff and volunteers about. But when you point out why something they said or did is a problem, you get the whole ‘Why are you making everything about race?’ reaction. And then that shuts down conversation.”

Kit sincerely hoped this wasn’t the prelude to something political. She was so tired of the divisiveness and didn’t feel like asking her usual reframing questions of “What are God’s invitations to you in the midst of this?” and “What does the agitation you’re feeling reveal about what you need from God?” Those could wait for a spiritual direction session. For now, she needed the grace to listen well and not react, whatever Mara offered. She opened her hands on her lap. Release. Receive.

Mara leaned forward and scraped at some chipped orange toenail polish before planting her feet on the floor again. “So, here’s an example, okay? Last week one of our longtime volunteers—a Christian guy—comes in to help serve lunch. The kids love it whenever he comes. He’s like a grandpa to them, plays with them, jokes with them. But I’ve had to talk to Larry in the past about some of the comments he’s made—things like telling some of the Black boys they need to study and work hard so they don’t end up in gangs or grow up to be crackheads.”

Kit raised her eyebrows.

“Yeah,” Mara said. “So last week he comes into the kitchen while a couple of us are in there making sandwiches and getting everything ready, and there’s a new volunteer helping out—an older Black woman named Ruth. He’s friendly to her, wants to make her feel welcome, part of the family. All good. But after talking to her awhile, he looks at her like she’s from a different planet and says, ‘Wow! You’re really articulate.’ Ruth cocks her head, sizes him up and down, and gives him this look as if to say, ‘Not worth my time answering that.’ Then she goes on chatting to Debra, who’s next to her, slicing up carrots, and Larry grabs a cookie and strolls out into the dining room to wait for the kids to arrive. And I’m thinking to myself, I don’t want to let this go. This is too important. Because this is exactly what we’ve been trying to train the volunteers to notice, you know? These comments and attitudes we’re not even aware of, things that cause hurt and harm. It’s all part of trying to be more like Jesus to one another. That’s what we want to do. That’s who we’re called to be.”

Kit nodded her agreement with that declaration and desire.

“So I was standing there near the oven, listening to Ruth and Debra chatting, and I didn’t want to interrupt and make Ruth uncomfortable by asking how she was feeling—I figured I’d wait until we could have a private conversation—so I followed Larry out into the dining hall. Nobody else was in there, so I sat down with him at one of the tables and pointed out—as firmly and calmly as I could—that even if he meant for his comment to Ruth to be a compliment, what he’d said to her was an example of a racial stereotype. A microaggression, just like we’d talked about before. He exploded. Threw up his hands and told me he was done being accused of being a racist when all he’d ever wanted to do was—and I quote—‘help those people make something of their lives.’”

Kit stared at her, unsure how to respond. Not only had she never visited Crossroads, but she had never considered how racial prejudice might affect the community Mara served. She could own that as ignorance. But the truth was, she had always worked hard not to see or call attention to race, and hearing Mara speak so bluntly about color made her uncomfortable. Thankfully, she was so practiced in concealing her thoughts and reactions that Mara probably wouldn’t have noticed—even if she had been watching carefully.

“I tried having a conversation with him. I told him we loved having him at Crossroads and said how important he’s been to the kids but that I needed him to be open to seeing his blind spots, and that I wanted all of us to keep learning together. But when I told him he would need to do some more training with us about race and justice, he quit right there. Said he was sick and tired of all the political correctness crap and stormed out of the building just before the kids arrived. No reply to any of my emails either. So, I’ve got to let him walk away, along with a couple of other volunteers he obviously contacted and ranted to. They were so mad about what I said to him and how I’d” —she signed air quotes—“‘judged him,’ they quit too.”

“I’m so sorry,” Kit said after a moment. “That all sounds very hard.”

“Yeah,” Mara said, “but it’s not about me. I keep reminding myself of that.” She folded her hands in her lap. “I talked with Ruth about it afterward—she and Debra both saw him storm out—and she said she was more concerned about the kids’ reaction once they find out Larry probably isn’t coming back, even to say goodbye. With all the disruption they’ve already gone through, now they’ve lost one more person who meant something to them. And she’s right—that’s heartbreaking. If he’d just been open to the possibility of seeing something new, we could have moved forward together, as messy and hard and frustrating as it might have been. We could have worked to find a way.”

“I know you would have,” Kit said. “I admire your commitment to all the people you serve, even the ones who make it challenging for you. That’s a powerful expression of love. Especially in times like these.”

Mara leaned her head back and closed her eyes. “It’s just so loud right now, you know? Everything’s so loud. We’re not listening to each other. It’s constant fighting, constant labeling and condemning. And when did ‘justice’ become a bad word? When did some Christians decide that working for justice and standing up for people who live life on the margins is a political issue instead of a kingdom one? I don’t get it.”

“No, neither do I. But I’m so glad you’re there, doing what you’re doing. That’s faithful stewardship of your own experiences.”

Mara looked at her again. “Sometimes I wonder, though, if I’d be so passionate about the issues if they weren’t personal to me. Like, would I care so much about racism if one of my kids hadn’t been the victim of it? I’m not saying that everything Jeremy has struggled with is because of the color of his skin, but being biracial with a racist bully for a stepfather didn’t help things. And I guess part of me still regrets all the times I didn’t stand up to Tom and tell him to stop. Even though I understand why I didn’t, why I didn’t feel like I could. But if I can stand up now and advocate for kids who aren’t mine or find ways to help empower people who feel beaten down or left out or made to feel ‘less than’ because of race or poverty or lack of education opportunities or whatever, then I’ll give it every breath I’ve got. Even if it makes some people mad.”

Kit wished she could have shown Mara a tape of herself sitting on that same cushion years ago, bound up in shame and guilt and fear and condemnation, convinced she would never make any progress in knowing Jesus’ love for her or responding to his love. What a testimony to the grace and power of God. And what an honor, she thought after Mara left her office to go to another meeting, what a joy to have had a front row seat in watching God’s work of setting captives free and sending them out into the world, redeemed.

The creaking of the front door to her house later that night startled Kit awake on the couch. Her Bible, which was still open on her lap, slid to the floor. “Hi there,” she said as Wren entered, a backpack slung over her shoulder.

“Hey. Sorry, did I wake you?”

“No, it’s okay. Must have just nodded off.” She straightened her glasses. “What time is it?”

“Almost nine.” Wren slipped off her sneakers.

“Good day?”

“Yeah, okay. Pretty quiet, except for Miss Daisy.”

Kit picked up her Bible from the floor and set it on the coffee table. Over the past few months, she had heard many stories about the poor woman who clutched her baby doll and hollered for her father and mother to come and take her home.

“She slept most of the morning but then couldn’t get settled down this afternoon. Mr. Kennedy kept asking if someone was hurting her. I don’t know if he remembers that she has bad episodes almost every day.” Wren unzipped her bag and pulled out her housekeeping uniform. “One of the CNAs sang this ‘Daisy, Daisy’ song to her, and then they must have given her a sedative or something because she was fast asleep when I left.”

“That’s an old song,” Kit said. “My grandmother used to sing that one to me. ‘Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do.’ Something something about a carriage and a bicycle built for two.” She pictured Mom-Mom leaning in close, her face beaming as she crooned, her body swaying to the music, her breath smelling of licorice. “I used to make her change the words to ‘Kitty, Kitty.’ Didn’t work quite as well. But I always wanted a bicycle built for two because of that song.”

Still clutching her uniform, Wren sat down on the armrest of the couch. “Did you get one?”

“No. Never did. Robert wasn’t one for riding, and it’s not much use having a tandem if you don’t have anyone to pedal with you.”

“We should get one.”

Kit chuckled. “I’m a little old for something like that now.”

“You’re not old-old, Kit.”

She chuckled again. “Thank you, I think.” Wren’s soft brown eyes had a hint of sparkle—a more regular occurrence lately. Still not something to take for granted, though. Not when she had to work so hard to be well. Kit wished she didn’t have to work so hard.

“What I mean is, you’re a youthful, healthy seventy-five. Not like some of the people at Willow Springs.”

Kit didn’t take that for granted either.

“What color bike did you want?” Wren asked.

“Oh, I don’t know. I don’t think it would have mattered.”

“But if you could choose.”

“Don’t get any ideas, Wren.”

“I won’t. I’m just asking.”

Kit ran her fingers along one of the throw pillows. “Blue, I guess.”

“Light or dark?”

“Light. Like your uniform.”

Wren looked down at her scrubs. “Speaking of, I need to do laundry tonight. All three of my uniforms are now officially dirty.” She pointed to a large stain on the front of the shirt. “Tomato sauce. I ordered pasta from the cafeteria so I could eat with Mr. Kennedy while we were watching golf. I hope I can get one of them dried in time for tomorrow.”

“Are you there again tomorrow?”

“They need me in the morning because one of the other housekeepers is sick. Then I’ll come to New Hope and clean after lunch.” She paused. “If that’s okay. Sorry, I should have checked with you first.”

“No, it’s fine. You know the hours are flexible. As long as you clean before the group comes in on Saturday, it’s all right.”

“Okay, thanks.” Wren walked to the patio door and gazed into the twilight. “No cardinals lying about?”

“No, I don’t think so.”

“That’s good. I’ve been thinking about that metaphor all day.”

“What’s that?”

Wren turned to face her. “What you said about the bald cardinal and molting. I’ve been pondering that image.”

“Have you? I’d love to hear more.”

“Okay, cool. I’ll get a load started in the washer first. Have you already had your prayer time?”

Most nights she and Wren tried to pray together, whether that was meditating on a Scripture passage, or reading liturgical prayers, or praying with art or collage, or reviewing their day with the examen. “I’ll wait for you,” Kit said, and stifled a yawn.

When she returned, Wren was scrolling on her phone. “While I was thinking today about the image of molting, I remembered that Vincent used it to describe the losses in his life.” She sat beside Kit on the couch and handed her the phone. “Here. You can read it. It’s from one of his letters to Theo.”

Kit adjusted her glasses to view what Vincent had written to his brother: “What molting is to birds, the time when they change their feathers, that’s adversity or misfortune, hard times, for us human beings. One may remain in this period of molting, one may also come out of it renewed, but it’s not to be done in public, however. It’s scarcely entertaining; it’s not cheerful. So it’s a matter of making oneself scarce.”

“I hear his vulnerability in this,” Kit said. “Maybe even shame.”

Wren nodded. “I get it. I’ve felt the same impulse to hide so I don’t have to give explanations to anyone. It’s easier that way.” When Kit handed the phone back to her, she set it on the coffee table. “Dawn told me at our last appointment that she’d love to see me try to make new friends and spend time with people my own age. But I told her it takes way too much energy. I was thinking about it today, how exhausting molting can be. I feel like I need to concentrate just on doing my work until my feathers grow back.”

Kit wasn’t going to contradict her, but she was glad her counselor had started nudging her out of her comfort zone. “‘Until’ is a good word,” she said. “I hear expectant hope in that word, like you’ve turned a corner toward something new.” When Wren looked confused, Kit said, “I heard you say, ‘until my feathers grow back.’”

“Oh!” Wren smiled slightly. “Thanks for catching that. I guess that’s progress.”

“Great progress. And if Dawn thinks you’re ready for a new challenge, take that as a word of hope too.”

“Yeah, I guess,” Wren replied, but she didn’t sound convinced.

Kit decided not to push. “Thinking of birds and molting,” she said, “my grandmother—the same one who sang the ‘Daisy, Daisy’ song—had a parakeet named Socrates. Smart little thing. She used to take him out of his cage when I visited, and he’d do somersaults right in my hand. He could say my name too. ‘Kitty-kitty-kitty,’ he’d say, and we’d laugh.”

Wren drew her knees to her chest and rested her chin on them, her gaze fixed on Kit.

“Whenever he molted, he’d get these sharp little stubs poking up through his skin—pinfeathers, they’re called—and they were itchy and uncomfortable for him, like little spikes. Pinfeathers are really delicate. They have sheaths on them—kind of like a toenail—to protect all the new growth. But eventually, that protective cover has to chip off so the feather can expand and unfurl. So little Socrates would preen and preen and try to chip it away, but he couldn’t preen the top of his head. So as those pinfeathers grew strong, my grandmother would gently stroke them so the new growth could emerge.”

Kit hadn’t thought about that in years, how Mom-Mom would sing to him while she stroked him, and that little bird would nuzzle against her hand as if he knew she was doing something important to help care for him.

“What you said about molting, Wren—how exhausting it is—that’s what Mom-Mom used to say too. She always said Socrates needed extra-loving care while he molted and rested. So I would sometimes sit beside his cage and read to him while he sat on his perch, and I’d watch for those little spikes to turn into feathers.” She paused. “They always did.”

In the silence, Kit listened to the hum and slosh of the washing machine, her thoughts wandering to New Hope and the board and her retirement. After a while, Wren leaned forward and kissed her on the cheek. “Thanks for giving me a safe space where my pinfeathers can emerge. And for being patient with me in the process.”

Kit slowly rubbed her short white hair. “I’m going through my own molting process these days, so thanks for being patient with me too.”

As a breeze strummed melodic broken chords on a wind chime suspended from the eaves, Kit gazed out the patio door into the darkness, thinking of the bald cardinal and Wren and the Willow Springs residents and Mara and the Crossroads staff and residents and volunteers and all the vulnerable, prickly places of discomfort, loss, and change. And she stroked the top of her head again.

3

As soon as she finished her shift at Willow Springs on Friday afternoon, Wren biked to New Hope. “People are sending in donations for a retirement gift, right?” she asked Gayle, the part-time receptionist, after greeting her in the office.

Nodding, Gayle removed a manila folder from her desk drawer. “I’m keeping track of everything in here. Almost everyone has RSVPed yes, so the chapel will be completely full.”

“That’s great,” Wren said. She hoped Kit would think it was great too. “So, is the board planning to give her a check, or are they also buying gifts?”

“Not sure. Why?”

“I had an idea.” Wren peered into the lobby to make sure Kit wasn’t nearby. “I found out last night that she’s always wanted a bicycle built for two.”

“Seriously? Do they still make those?”

“I already went online and found a couple different options.” She had even managed to find the right color.

“Does Sarah know?”

“That she wants one?”

“That you want to get her one.”

“No.”

“Oh.” Gayle slid her palm across the file folder. “I don’t know, Wren. I mean, if she were my mom . . .”

“Lots of older people ride bikes. I see them all the time. And it’s not like we’re talking about a mountain or racing bike. I’ve ridden tandems before. I could take the lead. They’re not hard once you get the hang of it.”

“But if she fell and broke a hip or—”

“Okay.” Wren held up her hand. She didn’t need someone planting that kind of anxiety in her. “Never mind. Forget I mentioned it.”

“I just worry that—”

“It’s fine.”

Gayle tucked the folder back into the drawer. “I’m sorry to squash your enthusiasm, Wren.”

“No big deal.” She picked up her backpack. “I’ve got to start cleaning. Don’t mention the bike idea to Kit, okay?”

Gayle mimed zipping her lips.

If the bicycle couldn’t be a gift from the group, Wren thought as she rounded the corner to the hallway, it could be a gift from her. And only she and Kit would need to know about it.

That’s the spirit, Wrinkle, Casey replied.

She stopped so fast, she nearly tripped.

Seven months after his death, he could still startle her with a voice that sounded so clear, she could have sworn he was right beside her.

Or behind her.

That was where Casey would often sit when they rented a tandem bike in Muskegon on a Saturday afternoon and cycled along the lakeshore. Though he would joke about taking the backseat so she could chauffeur him for a change, he also knew how to encourage her to take the lead. When he was well, Casey was her champion.

Smiling to herself, she imagined how the two of them might have appeared to anyone watching them ride together, him towering over her with his six-foot-three lanky frame, his wavy red hair flowing behind him, while she directed all her five-foot-two strength into pedaling. It had taken them a few tries to find their rhythm on their first ride—and a fair share of their typical sibling-style bickering—but once they learned how to synchronize their feet, they were off and away.

Dawn was right, Wren thought as she gathered her cleaning supplies from the closet. There came a day in the grief process when memories of a loved one brought a smile before a tear. Maybe she was making progress after all.

She inserted her earbuds, found Don McLean’s “Vincent” on her phone, and hit repeat. Then she began dusting his paintings, watching to see which one would catch her attention for prayer.

But the one that edged into her thoughts didn’t hang on these walls: La Berceuse, Vincent’s portrait of his friend Augustine Roulin rocking a cradle. That was the one that had provoked Casey the last day she saw him alive.

She glanced at the closed door of her painting studio, a classroom Kit had given her permission to use. Last December, she and Casey had stood at her worktable, studying the various portraits of Augustine in her art book and arguing about Vincent’s style until he muttered something about mothers being impossible to please and fatherhood being “overrated.” She hadn’t understood then what he meant. She hardly understood now, not with all the mysteries still swirling around his life and death. Casey had died with secrets. And as Kit had reminded her multiple times, both in letters and conversations, sometimes you had to bury and relinquish your unknowing so you could move forward with grief.

“Why does that lady make you sad?” Phoebe had asked her last spring when they saw one of Vincent’s portraits of Augustine in Chicago. While the rest of their family toured a potential college for Olivia, she and Phoebe spent a few hours at the Art Institute.

Wren was so taken aback by her little sister’s gifts of perception that she wasn’t sure how to answer. So she deflected the question. “Does she make you feel sad?”

“Yep.” Phoebe gripped Wren’s hand. “Because she looks mad.”

“Does she?”

“Yep.” She stood on her tiptoes for a closer look. “Maybe the baby’s crying too much.”

“Maybe,” Wren had replied. “Babies do cry a lot sometimes.”

She wiped a smudge from the frame around Two Cut Sunflowers. Casey wouldn’t have had much patience for a crying baby. But even a colicky newborn couldn’t have been the reason why he had abandoned Brooke and their daughter, Estelle. Casey had often been selfish, but he wasn’t cruel. Something had pushed him over the edge. Something had triggered a bipolar episode. Maybe Brooke was abusive, just as he’d claimed. Far easier to believe the worst about someone she had never met—and would likely never meet—than to believe the worst about the very first friend she had made after moving from Australia to America when she was eleven. The best friend who had been like a brother.

Except, a best friend wouldn’t have concealed the fact that he had become a dad.

A wave of anger swept over her.

Betrayed. That was still the best word to describe how she felt, even all these months later. In May, when she knelt beside Kit in the New Hope courtyard garden to bury her “I forgive you” letter to Casey and to plant the seeds she had plucked from his memorial sunflowers, she thought she was also burying her anger and bewilderment. How naive she had been.

“Forgiveness is a process,” Dawn often reminded her. Like grief. And her capacity to feel anger and sorrow without being consumed by them was evidence of her movement forward.

But if she knew precisely what she was forgiving him for—if she could only know the truth about what he did and why—she might truly release him.

Cloth and spray bottle in hand, she opened her studio door and walked to the window overlooking the courtyard. She had hoped the sunflowers would be in full bloom for Kit’s retirement party, and the timing seemed about right.

She removed her earbuds and listened to a full-crested cardinal singing on the rose arbor. Maybe she could paint two versions: the bald and the full. Shedding and renewal. Loss and hope. In fact . . .

She thought about Vincent and his plans to flank Augustine with his sunflower paintings: a triptych showing an ordinary saint poised between flaming flowers that brightly blazed, all three paintings gleaming with the radiance of God.

She could paint a triptych of cardinals. Life before molting. Life during molting. Life after molting. The cardinal before the loss would not be identical to the one after. How could it be? Struggle left its mark. Even if new feathers emerged.

Even when, she reminded herself. She needed to keep practicing hope. The evidence of things unseen.

“There you are!” Kit called from the doorway.

Startled, Wren spun around. “Yep, I’m here.”

Kit gestured at the spray bottle. “Maybe you can clean your studio later. There’s quite a lot to be done before the retreat tomorrow.”

Wren’s face flushed. “I know, I wasn’t going to clean in here. I just came in to look outside for a second.”

“Ah, okay. I noticed the trashcans are full, so—”

“I know. I’ll empty them.” Like I always do, she added silently.

“Thank you, Wren.”

Wren waited until she heard her footsteps recede before stepping into the hallway to resume her slow dusting of Vincent’s art.

That’ll do for now, Kit told herself later that afternoon. She saved the retreat document on her office computer and looked at the open Bible on her desk.

When she had prayed about good last words to offer the community, the theme of stewardship had come to mind: stewarding love, stewarding affliction, stewarding grace. As you have been loved, love. As you have been comforted, comfort. As you have been forgiven, forgive. That was what she would present on the next three Saturday mornings. Unless the Lord redirected her, which he was always free to do.

Love is patient, she read from 1 Corinthians 13 again. Kind. Not envious or boastful, arrogant or rude, self-seeking or irritable or resentful. Each description from Paul merited a lifetime of pondering. During one of the personal reflection breaks, she would invite the group to meditate on each word and consider how God had loved them in those ways, to practice receiving that kind of generous love from him before considering what it meant to extend that kind of love to others. Especially to those who were impatient and unkind, envious and boastful, arrogant and rude, self-seeking, irritable, and resentful.

She rubbed her temples slowly. Long-tempered. That was the meaning of the Greek word Paul used for “patient,” the opposite of short-tempered flares of anger and passion. Long-suffering fortitude extended a long way and a long time over a long haul. She would emphasize to the group that this kind of steadfast perseverance in loving others was a gift of the Spirit and a fruit of abiding in God’s extravagant love. She would remind them what Jesus had said: “As the Father has loved me, so I have loved you. Abide in my love.” Savoring that kind of divine love took practice. And time.

“I’m heading home, Katherine,” Gayle called from the doorway. “Unless there’s anything else you need from me.”

Looking up from her Bible, she mentally ticked off the to-do list. “Prayer handouts are printed? Registration list is complete?”

“It’s all on my desk, ready to go.”

“That’s great, Gayle. Thank you.” She would call it a day too.

After Gayle left, she went to find Wren, whose cart was parked outside the women’s bathroom. Not wanting to startle her, Kit called her name from the hall.

Wren appeared, her forearms concealed in yellow rubber gloves. “Heading home?”

“Yes. I’ll pick up something quick and easy for dinner on my way. Do you have much left to do?”

“A bit. What time is it?”

“Just after four.”

“Okay,” Wren said. “I’ll see you there.”

On her way back to her office to collect her purse, Kit paused in front of one of Vincent’s sowers. She might as well take an unhurried moment for the kind of prayer that had become so life-giving to her over the past few months.

Folding her hands, she let her gaze rove over the painting until it landed on the man’s large open hand scattering the seeds from his satchel. An abundance of them.

She leaned in for a closer look.

How differently she had approached planting the sunflower seeds with Wren, depositing each one in soil she had amended so they would have the best chance for growth. That kind of deliberate care had felt like faithful, responsible stewardship of what had been entrusted to her.

But this sower seemed blissfully unconcerned about where the seeds might land.

She pictured herself in the painting, trailing behind him with her own satchel, stooping to cover up with earth the seeds he had carelessly flung. She imagined herself kneeling in the dirt, then reaching into her pouch to remove a solitary grain. After carefully burying it, she patted the ground in satisfaction and offered a prayer for its growth.

But the sower tossed seed by the handful and laughed when the wind caught and swirled it, depositing it in places where she was certain it would never take root. The birds were bound to find those seeds and swallow them. And what about the rocky soil or the thorns that would rise up and choke vulnerable seedlings?

“Don’t you care about the harvest?” she asked him.

In reply, he gently pried open her fist and poured a mound of seed into her palm, some of it falling to the dirt. Then he blew on her hand, and the seeds floated on his breath to scatter to places unseen, to land on soil that may or may not be prepared. “Listen,” he said with mirth in his voice, “a sower went out to sow.”

4

When Sarah Kersten entered the New Hope office at eight fifteen on Saturday morning, her mother was muttering at the printer, hands on her hips.

“Misbehaving?” Sarah asked.

Her mom grimaced. “Me? Or the printer?”

Sarah laughed and set her purse on Gayle’s tidy desk. “Either. Both.” She kissed her mom on the cheek, then shooed her out of the way. “What’s the problem with it?”

“It won’t do what I want it to do.”

What a succinct summary of the human dilemma, Sarah thought. “What do you want it to do?”

“Print, just print. It’s a simple Word document, no different from what I’ve printed hundreds of times.”

Sarah examined the printer, then pushed the power button. The machine hummed.

“Good grief,” her mother said. “I’m sorry.”

“No problem.” Sarah checked the paper tray to make sure it was loaded. “Gayle must have switched it off.”

“I don’t know why she would have done that, no reason to do that.”

Sarah stared at the large blue light on the machine. “No harm done, Mom.”

“You’re right. No harm done.” As the printer spat out pages, Kit gathered them one by one, her wrinkled, age-spotted hands trembling ever so slightly.

“I’ll get those,” Sarah said. “Sit down a minute and take a deep breath.”

Obeying, she sank into a chair with a sigh.

Sarah monitored the printer’s progress. “Gayle’s not helping today?”

“No. She’s got a bridal shower. Her son’s getting married in a couple of weeks.”

“What about Wren?”

“She’s going to the nursing home today.”

“She works on Saturdays?”

“No, she visits with the residents. Watches golf, plays checkers, that sort of thing.”

After all Mom had done for her, Wren might have offered to help with an event like this. But she didn’t say that. This was not the time for another round in that conversation. “Put me to work, then. What else needs to be done?”

“Nothing. Wren cleaned yesterday, and Gayle already printed out the handouts and registration list.”

Sarah collected the remaining pages and tapped them against the table to straighten the stack. “I’ll do the welcome desk. You go sit in your office awhile and re-center yourself.” She glanced into the lobby. “Where’s the registration table?”

Her mom craned her neck to peer through the office door. “It should be right near the entrance. It’s not there?”

“Nope.”

She pushed herself up from the chair. “I didn’t even notice when I came in. I guess Wren forgot that part. I’ll go get it.”

“No, you won’t. I’ll take care of it. You go to your office.”

She paused, then gave Sarah a mock salute. “When you use your bossy teacher voice, I know better than to argue with you.”

Sarah blew on her fist and brushed off her blouse to simulate an easy victory. “It’s my superpower. Works for middle schoolers, mothers, and husbands.”

Mom grinned. “Not for teenage daughters?”

“No, less and less, I’m afraid. I’m working on developing different strategies.”

She patted Sarah on the arm. “Good luck to you, my dear girl. Seems to me that strong wills run in our family.”

Sarah was going to quip, “From your side or Dad’s?” but thought better of it. No matter how many years had passed since her parents’ divorce or her father’s death, he remained a potentially tender topic.

Especially the past few months. While her mother insisted that Wren’s presence in her home had led to deeper and fruitful processing of her own grief and losses, Sarah wasn’t convinced that ruminating on the past had benefited her.

“Have you got the registration list, Mom?”

“Yes, here. Thank you for helping with this.”

“No problem.” As Sarah scanned the list of names, she recognized many of them. Over the years her mom had certainly developed a loyal fan base, though she would firmly object to any mention of such a thing. “Go rest and get ready.” Sarah kissed her again. “Love you, Mom.”

“Love you too, honey. Thanks for being here.”

No hint of reproach colored her expression of gratitude, no “Nice of you to come to one of my retreats again, now that I’m retiring.” Just sincere appreciation.

In the lounge Sarah found a small round table, which she carried to the lobby. Just as she was setting out pens and name tags, Hannah and Nathan Allen arrived, sporting matching Wayfarer Church T-shirts.

“Hey, stranger!” Nathan called.

“Hey, yourself! They let you come to these?”

“Check your list. Should be right at the top.”

Sarah eyed the sheet. “Nope. Hannah is.”

“Ah, well, as it should be,” he said with a grin. “Bet I’m the only guy, though.”

“Nope. There are two of you. Russell’s coming.”

“Oh, good! Someone to sit with.”

Hannah elbowed him. “Don’t mind this one. He’s had way too much sugar this morning.” She swept her hand across the front of her shirt. “Pancake breakfast fundraiser for the food pantry.”