1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

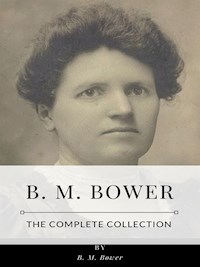

In "Fool's Goal," B.M. Bower intricately weaves a tale set against the rugged backdrop of the American West, masterfully capturing the spirit and challenges faced by its inhabitants. Through a compelling narrative style that blends vivid descriptions with realistic dialogue, Bower explores themes of ambition, love, and the quest for identity in a rapidly changing landscape. The novel engages with the literary context of early 20th-century American literature, reflecting both the hardships of frontier life and the romantic idealism associated with it. Bower's adept characterization of both rugged individualists and their unexpected vulnerabilities serves to illuminate the complexities of human relationships within this setting. B.M. Bower, a significant figure in Western fiction, drew inspiration from her own experiences in the West, which informed her nuanced understanding of frontier life and culture. Her background as a pioneering female author in a predominantly male genre allowed her to present diverse perspectives and showcase the strength of her characters, particularly those who navigate societal norms and personal aspirations. Bower's personal connections to the themes she explores add authenticity to her storytelling, enriching the reading experience. "Fool's Goal" is a must-read for enthusiasts of Western literature and those interested in character-driven narratives that explore the intricate ties between aspiration and reality. Bower's insightful prose not only immerses readers in a vivid historical setting but also invites them to reflect on their own life ambitions. This novel stands as a testament to Bower's skill, offering a compelling invitation to explore the human condition against the vast, untamed expanse of the West.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Fool's Goal

Table of Contents

I. — MONEY WILL TALK

THE hoarse bellow of noon whistles shattered the cloistered quiet of the vice-president's office in a certain bank down near the stockyards. Mr. Kittridge cleared his throat and lifted his eye-glasses from his thin nose, the other hand going out to finger certain papers lying before him on the desk.

"If you want to put your money into land and cattle," he said, "that is your own affair. I can doubtless arrange the matter through some of our Western correspondents. I suppose there isn't a bank out there that hasn't been obliged to take in such a property as you apparently want, on foreclosures. I haven't a doubt that, given the locality you desire, we can find you what you want."

"But that isn't the way I want it, Mr. Kittridge. I didn't want any cut-and-dried arrangement through the banks. I want to knock around through the West and get my information first-hand, through actual personal contact with the conditions I shall have to meet. I want to be in a position to snap up any bargain I might happen to run across, so I'll take cash—"

"And risk your life doing it," snapped Mr. Kittridge, stung out of his calm. "You certainly must realize what will happen if you carry a large sum of money around with you."

"Don't you think I'm able to take care of it?"

"I certainly do not, Mr. Emery. I do not think any man is safe with a large sum of money on his person. It is absolutely unnecessary to take the risk. Any bank will forward a draft on us, in the event of your making an investment of any kind. We shall be glad to wire payment if you desire. Currency is dangerous, not only to you but to the man who is paid in cash. Murder and robbery follow on the heels of cash money, as you must know, Mr. Emery. Your father, I am sure, never dreamed of such a move as this, or he would have made some provision against it."

"Yes, I guess he would, all right. Dad thought he dealt in cattle, but he didn't, really. He dealt in dollars. He sat in an office and juggled train-loads of steers on paper. Everything was done on paper. Why, he never had twenty-five dollars in his pocket at one time in his life, so far as I know. Checks—checks—bank balances—well, I'm going to carry on from a little different angle, Mr. Kittridge.

"I want to see and feel and know the West. All my life I've watched trains of cattle unloaded here at the yards; now I'm going to see where they all come from. I know quite a few Westerners too; men that have come in with the cattle. They're different from any one here, but I don't know why they should be—barring certain colloquialisms born of their trade. It was all right for Dad to sit in an office and count cattle by car-loads, but I've got to watch 'em grow. And money will talk, when I'm ready to have it speak. It isn't such a wild notion, when you consider the kind of men I'll be dealing with. A few thousands in cash will look a heap bigger than a check for the same amount. I—why, I'd take gold coin if I could carry it!"

"There's really no reason for such a course, and I cannot advise—"

"Well, I didn't expect you to approve or to advise it," Dale replied easily. "I realize that there's no reason on earth for what I'm doing except that I want to do it. I couldn't expect a banker to see my point of view. You've got your burglar-proof vaults and you always see money kept inside those vaults or behind your steelgrilled windows. You like to push it through, a few dollars at a time, and if a man asks for a lot you wonder why. You folks are like Dad; you juggle millions on paper, most of the time, and the cash you want to see locked safely away. You think dollars are dangerous—" He laughed suddenly and silently, his eyes opening wide and then half closing upon the light of mirth within. "Well, I've decided that I'm a gambler at heart," he chuckled. "I've studied psychology in books till I'm pretty well fed up on it. I'm going to take a course of what you might call field work. I'm in the mood to gamble a little with life; with danger, if you want to put it that way."

Again he laughed that silent laugh with the sudden flash of his eyes, and Mr. Kittridge, who had seen the trick in Dale's father and knew what it meant, gave up all idea of argument; and to prove it he closed his lips in a thin, straight line.

"So many bright young men go West to find their fortune," Dale added. "It will be interesting to reverse the process and take mine with me."

He had no expectation of being taken literally, but Mr. Kittridge adjusted his glasses again upon his high, thin nose and picked up a paper.

"Your real estate can hardly be carried off in your pocket, so we will leave that aside, having already disposed of the matter for the present. You have to your credit with us fifty-five thousand, seven hundred dollars. In what denomination do you wish to have the money, Mr. Emery?"

Dale stared for a moment, then laughed and got up.

"Oh, as large as you conveniently can," he said carelessly. "I'll call in to-morrow, if you like, Mr. Kittridge. Oh, by the way, give me two or three hundred in small bills, will you? Expense money, you know. See you to-morrow. Good-by."

Outside the bank he stopped and stood in the shelter of the deep doorway out of the wind while he lighted a cigarette, and his shoulders lifted themselves impatiently.

"Darn fool! Or maybe not, either. Maybe he thought he could scare me out with that bluff. Shot the whole pile at me, and what will I do with all that money?" Dale shrugged again. He had meant to take five thousand, or maybe ten at most. But Kittridge had taken him at his word. "Mad, maybe, because the bank isn't going to get its usual percentage if I do deal for a ranch. Yes, Kittridge certainly was sore. Threw the whole thing at me when he found he couldn't run the show!"

His cigarette going to his satisfaction, Dale stepped out into the throng and walked briskly northward. Kittridge had challenged his nerve and his intelligence, and he probably expected Dale to back water and accept a book or two of traveler's checks and go ambling from town to town like any tourist. Well, Dale didn't intend to do anything of the sort, though he felt pretty much a fool now that he was away from the presence of the man who had unconsciously egged him into so fantastic a decision. Kittridge was so blamed conservative; that was probably what had started it all. For Dale had been trained to conservatism all his life and he was sick of it. Business conventions had been the breath of life to his dad, but they certainly were not going to be saddled upon the son. Dale had walked a block when of a sudden he laughed.

"All right, we'll let it ride that way," he said to himself. "I guess I can handle it—but it sure is a queer way to start out—handicapped with money, instead of with the lack of it. I wonder, now, just how—"

His thoughts broke there when he whistled a yellow cab to the curb. The address he gave was somewhere near the middle of the Loop, and as the cab speeded up, he settled back to smoke and think. It was going to be something of a problem, as he realized now that he faced it squarely. He hardly knew whether to resent Kittridge's unimaginative interpretation of his little declaration of independence or whether to laugh at the joke on himself. His mood alternated between the two but it is interesting to note that not once did he consider going back and telling Kittridge that he had not meant to be quite so radical in his ranch hunting. Instead of that, he dismissed the cab in front of Brentano's and started a round of purposeful shopping. He did not intend to take a great deal of luggage with him, but he did mean to take plenty of time in selecting exactly what he wanted.

II. — THE CHLOROFORM MYSTERY

DALE lifted heavy eyelids and stared stupidly around the room, blinking a good deal over the effect to orientate himself. His lips felt stiff and sore, though for the life of him he could not think why they should. He raised a hand to investigate and felt dully amazed that his whole arm should feel heavy, his fingers awkward. A vile taste was in his mouth—something he ought to recognize, though his inert brain could not at once grasp the elusive quality of familiarity. Sluggishly he pondered, his eyes closing again while he did so, his tongue moving questioningly along his smarting lips.

"Chloroform!" Though he did not make a sound, his brain formed the word with the abrupt clarity of speech. He struggled to an elbow, hung there groggily with his eyes shut, then swung his bare feet out upon the Brussels carpet of the hotel room he occupied. For a full minute he sat slumped upon the side of the bed, staring owlishly, head between pressed palms, elbows propped insecurely upon his knees. Chloroform! He could taste it now to his very toes, and the flavor nauseated him almost past endurance. Once more his fingers passed gently across his lips and a fuller understanding seeped in upon him. He had not lived all his life in a city to be puzzled now by his condition, nor did he need to glance around the room to confirm his suspicion.

He got up presently and tottered to the dresser, leaning against it while he inspected his mouth. Lips seared and swollen with the stuff used upon him, eyes bloodshot and hair tousled, he presented so unlovely a sight that he turned away in disgust, languidly flapping a hand back at his reflection. On the bed again, with the covers pulled over him to shut out the chill of a crisp Wyoming morning, he battled with the aftermath of the anæsthetic and in time overcame it sufficiently to do a little coherent thinking.

Of course he had been robbed. He wondered how the thieves had managed to get in, then decided that they had entered by way of the window. He remembered that he had lowered the upper sash a foot or so for ventilation and had left the lower sash closed, and now the flapping curtains proclaimed the fact that the lower sash had been pushed up as far as it would go and the upper sash was closed. Perfectly simple, and very fortunate for him; that breeze blowing in had probably done much to call him back from the final sleep. They had used enough chloroform to kill an elephant, it seemed to him. His system was clogged with it. He could smell it on every breath he exhaled; the sweetish taste of it was in his mouth.

"Made a good job of it," his brain said distinctly, and somehow the sentence removed the obligation of immediate action. He pulled the covers higher over his shoulder, closed his eyes and let himself slide back into oblivion.

When he woke again, the breeze was still and the room was warm. From the way the sun was shining full across the foot of his bed he knew it must be nearly noon, and though the sweet, furry taste of chloroform was still in his mouth, it was not so pronounced and his body did not feel quite so heavy. But his head ached and his lips still felt puffed and sore, and altogether he was in no happy frame of mind as he sat up in bed, glowering at the room.

Everything he possessed had been ransacked. His clothes lay just where they had been dropped from the hands of the thieves. Though it was only a guess, Dale had no doubt there had been more than two men in his room; he did not believe one man alone would have tackled the job. His wallet he had pushed down between the sheets when he got in last night, and now he turned the sheet back over the foot of the bed for a complete search. From the look of the room he at first thought they must have missed the wallet, but they had been more thorough than he would have believed possible. The wallet was gone.

He leaned and picked up the coat he had worn the day before—a gray shadow-plaid with a thread of lavender. It lay on the chair beside the bed, though he had hung it in the closet with the rest of his suits which he had unpacked, thinking he would probably spend some days in Cheyenne. The lining of the coat had been slit down each under-arm seam, and the interlining on the shoulders and under the arms had been pulled loose. Dale frowned when he saw that, and got out of bed to make a more systematic examination of his other garments.

Every coat he had was cut in exactly the same fashion, and so were his vests, which he seldom wore. Even the one dinner coat he had brought with him had been searched. His suit case and big Gladstone bag showed slitted linings, his steamer trunk had been likewise examined. His few books sprawled open on the floor, where they had been flung in spite.

Dale picked them up one by one, straightened the creased leaves with careful fingers and laid them on the dresser. Shelley, three volumes of Shakespeare, Browning and two books of Kipling's poems. The assortment was not what one would expect a young fellow like Dale Emery to be carrying, and a somewhat unusual feature of the little collection was that they were uniformly bound in red morocco with his name stamped in gold in the lower righthand corner; a booklover's indulgence, one knew at a glance. As Dale recovered them one by one, his face brightened a little. His books, at least, had escaped the general mutilation.

With Browning held absently in his hand, he sat down on the bed to consider the situation. They couldn't have been hunting his wallet in the lining of his luggage, even granting that they had not looked in the bed until after they had searched the room. They had taken his watch and his tie pin, a fire opal of exceptional beauty, but it was undoubtedly his money they were after, and not only the money he carried in the wallet, though it had contained a couple of hundred or so; enough to justify the chloroform, perhaps, but not enough to account for the painstaking search they had made.

No, they had wanted more. They wanted all of it—all he had drawn from the bank. But how had they known about that? His bank in Chicago surely would not peddle the news, and he doubted whether any one save Kittridge and the assistant cashier who had given him the money would know about it. On second thought he decided that the paying out of so much cash would probably show on the books, but if any one in that conservative institution had wanted to rob him he wouldn't have waited all this while, surely. Dale hadn't left Chicago for some days after he got the money, and for two days he had kept it at home in one of his grips, just as if it weren't money at all but a package of little value. It had worried him so little that he had decided that since no one knew he had it, there was no reason whatever for being afraid of it. Now he was faced with the fact that some one had known.

Before leaving home he had disposed of the money in the safest way he could think of. Looking at the garment-strewn room he thought of the exact manner of its concealment and grinned. No, it was certain that while they must have known he was carrying it, they did not know how he had hidden it. No one, not even Kittridge, would ever guess that. On the way out to Cheyenne he had talked with one or two of the passengers casually, as men do while smoking, but he had not discussed his own affairs, or given his name, or told any one his business. He was very certain of that. Most of the time he had read, or looked out at the reeling landscape and dreamed of the cattle ranch he would one day own.

It was the Pullman conductor who had recommended this hotel, the Rocky Mountain, when he had arrived in Cheyenne yesterday. He had wandered around the town a bit, had eaten a good dinner and had sat in the lobby until bedtime talking with a tall, lean, handsome old fellow with a soft voice and a pleasant manner and the inimitable vernacular which proclaimed him range-bred. They had talked of the early days in Wyoming, and of the men who had flourished for a time in the West and died as they had lived. They had discussed cattle and range conditions, and the old fellow had seemed a gold mine of information. Dale had regretted that he was not a story writer so that he could use some of the stuff.

Had he mentioned to this man—Quincy Burnett was his name—that he had come prepared to invest in a cattle ranch? Dale tried to remember just what he had said; surely not that he had a large sum of money with him. He was not that big a fool. He had asked about the chance of getting hold of a good place, and Burnett had told him it ought to be easy, and had explained in great detail just why. Cattle raising wasn't what it used to be, he had said. Although cattle were "up", most of the ranchers were poor and saddled with debt. Some had gone broke and had to quit, because they had not been able to weather the black time when cattle had suddenly "dropped." Dale knew something of that too, from hearing his father talk prices.

No, he did not believe Burnett had anything to do with the robbery. If he had, then Dale did not know anything at all about human nature. Yet Burnett was the only man with whom he had talked in Cheyenne.

His thoughts swung back to Kittridge and the bank that handled his inheritance. He didn't believe they had anything to do with it either, and yet they were the only ones who had known about the money. No bystander could have seen him receive it, for he had gone into the cashier's office and the assistant cashier had brought the money in a neat package, had counted it there on the desk and had received Dale's check for the amount. Why, for all the people outside knew, he might have been in there borrowing or paying back a loan. He had carried a brief case; so far as appearances went he might even have been an agent for something.

Kittridge—had old Kittridge wanted to scare him out? Had he framed a practical joke just to show him what a fool he was? Dale felt his sore lips and shook his head. He couldn't imagine Kittridge doing anything of the kind; he was too old-fashioned, too conservative. It was a mystery, and he couldn't solve it sitting there in his pajamas thinking about it.

He got up and called the office on the phone, and said that he wanted to see the manager at once. Then he sat down on the edge of the bed again and held his head while he waited. When the manager tapped on the door, Dale let him in and went back to bed.

The manager, a neat little man with a round, boyish face and blond hair parted just off center and combed back in two little waves, glanced surprisedly around the room and approached the bed warily, one hand clasping the other.

"Well, you see what happened, don't you?" Dale demanded, with mild reproach. "I've been robbed. They pickled me in chloroform and gutted the room."

"I'd better get the police," said the manager, eyeing the disorder. "Did you lose anything of value, Mr. Emery?"

"Oh, no!" Dale snorted. "Didn't I tell you they cleaned me out? Something over two hundred dollars in my wallet, to say nothing of—what else they took."

"Papers?" the manager was staring at the suit case and empty trunk.

"Yes—something like that. I feel like the devil. Can you get a doctor that'll fix me up and keep his mouth shut? I don't want this peddled all over the place. And take my clothes to a tailor and have them fixed, will you? Never mind the police—"

"We'll have to mind," the manager told him. "I can't let burglary happen in my house and do nothing about it. We'll keep it as quiet as possible, of course, but we must take some action." He went to the house phone, called for a number, and talked crisply with some one whom he addressed as Chief.

"Varney himself is coming over, Mr. Emery," he said, when the one-sided conversation was ended. "He was just leaving for lunch when I caught him. He asked if we needed a doctor and I told him we did, so he'll attend to that. It's lucky we can have the Chief himself, since you want to keep it quiet." He stood in the middle of the room, looking around at the confusion, his lips pursed. "The Chief will want to see this just as it is," he said. "When he's through, I'll have things put in order for you. It's fortunate you are alive, Mr. Emery."

At that moment Dale rather doubted the statement, but he didn't care enough about it to dispute with the manager, who went on talking and surmising until the chief of police came in, a doctor at his heels. They seemed capable men, both of them, and Dale was glad enough to place himself in their hands, for the time being, at least. He did not need the doctor to tell him what a close call he had had, nor the chief of police to declare that the thieves must have been terribly intent on getting something they believed Dale had in his possession. The wallet alone would not account for the intensity of their search, Varney said over and over. They were after something else, and he was inclined to agree with the hotel manager that the robbers must have known of some valuable papers which they were determined to get hold of.

"Oh, yes, the deed to the old homestead!" growled Dale, and turned his back upon the room and the mystery.

"If I knew what they were after, I'd know what to look for," Varney persisted, standing over the bed.

"How do I know what they wanted? I didn't ask them; didn't get a chance." Dale closed his eyes. "I feel rotten," he grumbled. "For the Lord's sake, let me alone!"

Varney grunted something under his breath and with another comprehensive glance around the room went off to take what measures he could to apprehend the thieves.

III. — A FOOL AND HIS MONEY

WITH a muttered phrase which epitomized his opinion of all reporters, Dale threw down the newspapers he had been reading and reached for a package of cigarettes, since the burglars had taken his monogrammed silver case along with the rest of their harvest. Some one near by chuckled, and Dale's scowling glance turned belligerently that way, coming to rest upon a tall, good-natured young fellow with a wide, smiling mouth and hair of that rich auburn which is just a shade too dark to be called red. Dale's resentfully questioning look was met by eyes blue and disarmingly straightforward.

"Tough luck, all right," the fellow said, still smiling. "Bad enough to be robbed, without being spread-eagled all over the front page." He was standing beside a slot machine where for a nickel one guessed card combinations, and now he turned toward it, chose his cards, slipped his nickel into the slot and got a package of gum for reward. He was peeling off the wrapper to extract a stick when Dale decided to be human.

"What I can't understand is how they could reel off a string of numbers like they have here and claim they're the numbers of banknotes I lost," he complained. "I never gave the police any numbers."

"You didn't see last night's papers, I guess. No, that's right—you hadn't got over the chloroform, they said. Varney wired back to Chicago—you registered from there, didn't you? Well, the bank where you got your cash wired out the numbers of the bills. My brother works in a bank here," he exclaimed. "But it was in the paper too. I read it before I asked Jim."

"The bank in Chicago wired the numbers?" Dale bit his lip. "Sure a snappy piece of work," he commented dryly.

"The sooner the numbers are out, the better chance there is to get hold of the crooks," the other pointed out. "Publicity is the one thing they can't stand. It sews them up in a sack. All the banks and stores are on the lookout now for bills with those numbers. The crooks oughta know that by this time, though. They'll lay low."

While Dale morosely watched him, the young man fed another nickel to the slot machine, this time without avail. Chewing two sticks of the gum he had won the first try, he sauntered over to the big window with its row of padded leather chairs, chose one, and was just settling himself into it when his attention was attracted to a man walking past the window.

"Hey, Bill!" he called eagerly, tapping on the plate glass with his fingers. "What's the grand rush?" The man outside stopped and turned, grinning.

"Why, hello, Hugh!" he called exuberantly. The two met in the doorway, shook hands and stood there for a minute before they walked away, still talking.

Dale looked after them with a twinge of envy. They knew each other, they had things of mutual interest to talk about, they could walk into places together and greet other friends. For the first time since leaving home he was conscious of feeling lonesome. He couldn't talk to any one with that freedom which only long acquaintance can give, and yet he felt the need of discussing this mystery of his with some one he knew he could trust.

For instance, the banks must know the exact amount of money he had drawn from his account in Chicago and presumably brought to Cheyenne with him. This young fellow must also know, since his brother worked in one of the banks here. And while the paper had contented itself with vague phrases calculated to whet any man's curiosity, "Chicago Man Loses Fortune" was the headline they had used, what followed did not minimize the caption. The banks certainly must know the denomination of every bill. Dale had withdrawn only fifty thousand, two hundred dollars from his account in Kittridge's bank, at the last minute deciding to leave a balance there, and the chief of police undoubtedly knew how much the thieves must have taken. There was no telling how far the startling news had seeped into the town, but gossip probably was already naming figures.

But how did any one know before the robbery? The question struck sharply across Dale's thoughts, to return again and again. Even if Kittridge did have the numbers wired out here, that didn't clear the thing up. Somebody knew before that. Varney must have guessed that the thieves knew exactly what to look for, and so would every one who stopped to think a minute. Even the tailor who mended Dale's clothes must see the significance of the slit linings in all the coats.

Dale smoked meditatively, staring at the passers-by who came and went in the thin, intermittent stream of small affairs; big-hatted men with the peculiar, bow-legged walk that betrays the range man used to riding and to stiff leather chaps; preoccupied business men, women hurrying by with the intent look of shoppers; loitering time-killers staring into windows; clucking wagons and trucks. Occasional horsemen jogged past the hotel, and his eyes followed these with interest, longing to be riding with them. Then his attention was diverted from the street as snatches of conversation floated in to him from the pool room just off the lobby as some one passed through and left the door open.

"Damn' chump—packin' a wad like that in the first place." (Kittridge would certainly agree with that fellow!)

"These rich young squirts—" and the click of balls as the speaker interrupted himself.

Some one laughed. "A fool and his money!" he chortled.

"Well, a fool's gold'll buy as much as if he had good sense," another made trite comment.

"But not for him it won't," retorted the voice that had laughed. "Cleaned him to the bone. Serves him damn right too. Anybody that'll pack fifty thousand dollars around with him had ought to be robbed."

So the story was complete and gossip had the exact sum! Dale dropped his half-smoked cigarette into the nearest ash tray and walked out into the street, glanced this way and that until he discovered the place he was looking for, crossed to the other side and walked into a bank. At the Notes and Exchange window a man came forward to serve him, his ready smile bringing to his face a likeness to the tawny-haired young fellow Dale had seen at the hotel. Dale smiled back and felt almost acquainted.

"And get it here by wire, will you, please?" he said, as he pushed a draft under the grating. "You doubtless know why."

The man looked at the modest amount on the face of the draft and smiled again at Dale.

"I can cash this for you now, if you like, Mr. Emery. We've been in communication with your bank concerning you—in fact, we're their Cheyenne correspondent. If you'll wait just a minute I'll give you the money."

"You know, this is mighty decent of you." Dale flushed a little as he took the money. "Folks must think I'm the prize fool—"

"Or braver than most of us," the other supplemented with a pleasant little nod, glancing over Dale's shoulder as those behind grilled windows are wont to do when the next in line is waiting. "Please call on us if we can serve you in any way."

Dale thanked him and turned away, feeling a little glow of gratitude for the friendly offer. While other clients of the bank glanced at him as if they knew who he was and were naturally curious, he stopped by a desk long enough to single out a ten-dollar bill for immediate use and to tuck the other ninety dollars into an inside pocket before he went out to look for a store where they sold bill folds. He glanced back at the grilled window and saw that J. D. Mowerby was the name of the obliging young man who had served him. J. for James, of course—the young fellow with the gum had called his brother Jim. Jim and Hugh Mowerby; already he was beginning to learn something about the people here.

At the leather-goods store the clerk scanned the ten-dollar bill and wanted to talk of the robbery, but Dale was unresponsive. How had the thieves learned of the fortune in cash he was carrying to Cheyenne? He would give a good deal to know that, for therein lay the clue to their identity, if only he could find it. And find that clue he must, somehow. It was absolutely vital that he should know. But he felt that he dared not tell even Varney, nor Kittridge himself, just why. His one chance, it seemed to him, lay in keeping his own counsel and in waiting until the thieves betrayed themselves; which they would do, he felt sure. They must, in the light of what he knew. He would only have to bide his time.

Burnett was in the lobby when he returned, and his thin, handsome face was unsmiling and full of concern as he spoke to Dale.

"I just saw Varney down the street a piece," he began, without much prelude. "He says they haven't got a line on them fellows yet. Course, I don't s'pose you got a sight of 'em, did you? Got at you while you was asleep, as I heard it. Wonder is, they didn't kill you with that stuff. Varney told me they'd soaked a bath towel and there was enough on it when he got there to put most anybody to sleep. Sit down, Mr. Emery. I want to talk to you about this. Maybe you think it ain't my put-in, but I've been a peace officer myself a good many years, though I ain't working at it now. Resigned last summer to let in Burke, the sheriff. You talked with him yet? He's a good man; better than Varney, according to my notion."

"No, I haven't talked with any one, much. Not officially, I mean." Dale sat down beside Burnett, glad of the old man's friendliness. "I felt rotten yesterday, and to-day—well, the town thinks I'm crazy or a fool, to have all that money. It's a wonder they let me run loose!"

"Well, it was yours," Burnett observed dryly. "Varney made sure of that, soon as he found out how much it really was. He's kinda peeved that you didn't tell him yourself, Mr. Emery. No, you had a right to carry it, I guess, but it sure was taking a big risk." He stopped and canted one graying eyebrow upwards as he looked at Dale, his eyes a keen, cold blue that seemed to read a man's most secret thoughts. "Who all knew you had that amount of money on you?" he asked suddenly.

"Nobody out here," Dale said, returning the old man's stare. "My bankers, of course."

"And who else?" Burnett's gaze never shifted a hair's breadth. He seemed to be gauging Dale with some mental measurement of his own. "Somebody knew."

"One man," Dale admitted, flushing. "A friend—a fraternity brother. I'd trust him with my soul."

"Sometimes we trust friends to our sorrow," said Burnett, sighing without being conscious of the fact. "You trust him, but do you know he didn't tell?"

"Well—yes, I know."