1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

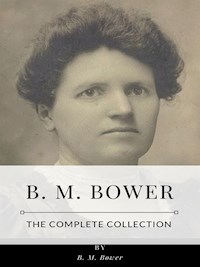

In "Where Stillwater Runs Deep," B. M. Bower intricately weaves a tale that navigates the rugged sensations of the American West, capturing both the stark beauty of its landscapes and the complexities of human emotion. The novel unfolds with vivid descriptions and richly drawn characters, employing a narrative style that blends realism with the poignant lyricism characteristic of early 20th-century literature. Bower deftly immerses readers in the themes of isolation, longing, and the search for belonging, inviting a deeply empathetic engagement with the lives of those who inhabit the fictional Stillwater. B. M. Bower, a pioneering figure in Western fiction, was profoundly shaped by her experiences living in Montana. Her firsthand knowledge of the region lends authenticity to her characters and setting, inspiring a narrative that resonates with the challenges and triumphs of frontier life. Through her writing, Bower sought to illuminate the often overlooked perspectives of women in the West, solidifying her role as a crucial voice in American literature. I highly recommend "Where Stillwater Runs Deep" to readers who appreciate evocative storytelling and nuanced character development. Bower's ability to capture the essence of the human spirit against the backdrop of a sprawling, untamed landscape makes this novel an enduring contribution to the canon of American literature.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Where Stillwater Runs Deep

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I. READY FOR BUSINESS.

At the moment, Ed Murray, supervisor of the Absarokee Division of the Yellowstone National Forest, was peeved. “Read that!” he snorted, shoving a letter from his particular higher-ups in Washington into the hands of his stolid secretary who, by the way, comprised the entire office force of the Absarokee Division.

The secretary obediently began reading in a slightly singsong tone:

“Under separate cover we are mailing you blank township maps. As a measure of economy you are instructed to have some member of your office force sketch in the necessary data, using the inclosed legends which have been made official for all forest-service maps. We——”

“That’s all—never mind the official trimmings,” Murray curtly interrupted. “Point is this: You’re the office force. What’re you going to do about it? Think you can fill in the maps?”

While the secretary calmly ruminated upon the subject of map making, Murray watched her with a twinkle of amusement, though that did not in the least degree soften his resentment against Washington.

“I could do anything on the typewriter if it would fit in the machine,” Christine at length decided. “If they are big maps, I could fold them lengthwise without carbon, but they might slip on the roller, which is too slick. If it is figures, I do not mind so much, but if it is those funny signs for surveying I must copy them with a pen, and that is no joke if I am in a hurry. I think if it is much work, Mr. Murray, I should get more wages.”

“Huh! Well, as you say, making maps on a typewriter is no joke, and I guess you’d earn your money all right!” Her employer noted the clearing of Christine’s placid blue eyes, gave another inarticulate snort and returned to his own problem, knowing that Christine was unlikely to repeat his words.

“Seems like I’ve got troubles enough in this district, fighting every cowman, sheepman, timberman and nester in the State. I’m always short-handed, always got a row on my hands with some one who thinks I ought to turn the reserve over to him just because we used to punch cows together! When I don’t, they think I’m trying to ride them on account of some little argument over brands that might have come up when I was stock inspector.

“Some member of the office force!” he growled, remembering the letter. “Huh! They must think I’m runnin’ two wagons and a regular round-up crew in this office! Far as that goes, I could take my rangers and work the reserve quicker than these darned cow outfits—picked ’em off the range myself, most of them. But when it comes to making maps——They’re like you, Christine. You could do it on the typewriter, you think; they might tackle it with a branding iron! Some member of my office force! My gosh! Take this letter, Christine. I’ll tell them poker-faced politicians in Washington what——”

“Do you want that in the letter?” Christine lifted her plump white hand to pluck the pencil from her silky blond hair.

“Lord, no! Dog-gone that June 11th Act and its maps and pamphlets and systems and all that bunk! What I’m going to need is a crew of civil engineers and an addition on this office. Washington must think all forest rangers are merely desk men! Why——”

“Should that be incorporated in the body of the letter, Mr. Murray?” Christine was patiently waiting with pencil point on her pad. “I could make a note and beg to inform them in a polite way that you have no office force and your secretary works until six o’clock sometimes——”

“No!” shouted Murray. “What does Washington care how long my secretary works? Take this—verbatim. None of your business-college trimmings—I want it typed the way I say it! I’ll tell them——”

The office door opened, admitting six feet of husky young manhood who saluted Murray and snapped into attention while he took in the entire office force with flicking glances of blue eyes that twinkled habitually. It may go on record that the entire office force instinctively patted its blond hair and modestly cast down its eyes of blue—with sundry furtive inspections when it thought the military visitor was not looking.

“Are you the forest supervisor, sir?” Somehow the habitual twinkle in the stranger’s eyes seemed to match a certain rollicky Irish tone of his voice, as if he had a joke on the tip of his tongue and needed scant encouragement to tell it.

“I am. What can I do for you?”

“You might read these letters of Recommendation, sir, and if they suit you, then you might give me a job.” He grinned as he handed Murray two letters and stepped back.

The first letter came from the national forest service and was signed by the chief. It stated that the bearer, Patrick R. O’Neill, had at his own request been transferred from Arizona to Montana, and was competent to perform all duties pertaining to the forest service. The other was from the supervisor of the Black Mesa National Forest, Arizona, and spoke in highest terms of the qualifications of this same Patrick O’Neill. Murray read both with care before he so much as glanced again at the man. When he did, he saw Patrick O’Neill still standing at attention, still with the twinkle in his eyes.

“Huh! Seen army service, too, haven’t you?”

“Yes, sir. Two years and a half at West Point.”

“Holy mackerel! Two years and a half—you learned how to make maps, didn’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Lock the door, Christine! Quick, before he gets away! Damn it, man, you’re needed in this office! Sit down and let’s talk. Christine, can’t you tell a joke unless it’s labeled? Unlock that door!”

“I was taught obedience to my employer by the business college. You say I am to lock the door and I lock it. I should not read your mind or some day I lose my job.” Christine unlocked the door which she had obediently locked, sat down at her desk and began wiping the speckless old typewriter before her, while she still patiently waited for the letter her boss was going to write.

“Tell me first why you quit West Point,” Murray was saying. “I’d have given my left arm for such a chance when I was a young man.”

“Technically speaking, I quit, Mr. Murray, but it was merely a strategic move on my part. I’d rather walk out than be kicked out.”

“Huh?”

“Insubordination, sir. We had a major—an old woman he was, Mr. Murray. Always putting us through our paces in civil engineering. One day he called on me in class to explain just how I would go about raising a hundred-and-fifty-foot flagpole. I said, ‘I would call a sergeant, sir, and I would say to the sergeant, “Sergeant, take a detail of men and raise that hundred-and-fifty-foot flagpole which you see lying there.”’

“The major lost his temper, sir. He accused me of being facetious. I replied that no one ever heard of an officer of the United States army so violating the traditions of his rank as to perform the menial task of raising flagpoles, and that I had clearly stated the method by which I would go about it, just as he had requested me to do. The major further forgot himself, sir. He called me an impudent young puppy. I thereupon saluted and walked out of the classroom. My sojourn at West Point ended shortly thereafter, sir.” Grin and twinkle combined to give Patrick O’Neill a look of personified good humor.

Murray roared with laughter; a circumstance unusual in that office where worry perched like a raven on his file case.

“How about making forest-service maps? Would you call upon the office force and tell them to fill in the blank township maps with the proper data—using a typewriter?”

Patrick O’Neill laughed. “No, I think I’d prefer to make the maps myself. It would be child’s play after the map making at West Point, and help me to familiarize myself with forest boundaries before you assign me to a district. If I can get hold of a couple of surfaced boards and a two-by-four, Mr. Murray, I’ll just knock together a table and set it beside that north window and go to work, sir.”

“Huh! Christine, phone the lumber yard and tell them to let Pat O’Neill have whatever material he wants to pick out, and send it up here immediately. Say it’s for the forest service.”

So this is how Patrick O’Neill, some time of West Point and lately of Black Mesa, Arizona, came into the service of the Yellowstone National Forest.