1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

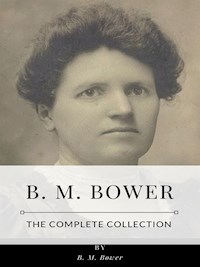

In "The Eagle's Wing," B. M. Bower crafts a captivating narrative set against the majestic backdrop of the American West, deftly intertwining themes of adventure, self-discovery, and the intricacies of human relationships. Bower's prose is characterized by vivid descriptions and a keen attention to detail, allowing readers to immerse themselves in the rugged landscapes and the spirited lives of the characters. This work not only reflects the stylistic hallmarks of early 20th-century American literature but also balances romanticism with a realistic portrayal of frontier life, firmly situating it within the broader context of Western fiction that explores both mythic heroism and the pitfalls of idealism. B. M. Bower, an influential figure in the realm of Western literature, was profoundly influenced by her experiences in the West, which shaped her understanding of the regional culture and landscapes. Her passion for storytelling flourished as she drew upon her own adventures and observations, bringing authenticity to her characters and narratives. Bower'Äôs commitment to portraying the spirit of the West, infused with her unique voice as a female author in a predominantly male genre, adds depth to her work and resonates with readers seeking representation beyond conventional narratives. I highly recommend "The Eagle's Wing" to those who appreciate richly woven tales that highlight the interplay between human nature and the challenges of untamed landscapes. This novel not only serves as a poignant exploration of personal growth and resilience but also as a nostalgic homage to the enduring allure of the American frontier. Readers will find themselves captivated by Bower's engaging storytelling and profound insights into the complexity of life in the West.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

The eagle's wing

Table of Contents

THE EAGLE’S WINGCHAPTER ONEKING, OF THE MOUNTED

On the wide south porch of the house where he had been born, Rawley King sat smoking his pipe in the dusk heavy with the scent of a thousand roses. The fragrant serenity of the great, laurel-hedged yard of the King homestead was charming after the hot, empty spaces of the desert. Even the somber west wing of the brooding old house seemed wrapped in the peace that enfolds lives moving gently through long, uneventful months and years. The smoke of his pipe billowed lazily upward in the perfumed air; incense burned by the prodigal son upon the home altar after his wanderings.

The old Indian, Johnny Buffalo, came walking straight as an arrow across the strip of grass beside the syringa bushes that banked the west wing. Rawley straightened and stared, the bowl of his pipe sagging to the palm of his hand. As far back as he could remember, none had ever crossed that space of clipped grass to hold speech with the Kings. But now Johnny Buffalo walked steadily forward and halted beside the porch.

“Your grandfather say you come,” he announced calmly and turned back to the somber west wing.

Sheer amazement held Rawley motionless for a moment. Until the Indian spoke to him he had almost forgotten the strangeness of that hidden, remote life of his grandfather. From the time he could toddle, Rawley had been taught that he must not go near the west wing of the house or approach the brooding old man in the wheel chair. As for the Indian who served his grandfather, Rawley had been too much afraid of him to attempt any friendly overtures. There had been vague hints that Grandfather King was not quite right in his mind; that a brooding melancholy held him, and that he would suffer no one but his Indian servant near him. Now, after nearly thirty years of studied aloofness, his grandfather had summoned him.

The Indian was waiting in the shadowed west porch when Rawley tardily arrived at the steps. He turned without speaking and opened the door, waiting for Rawley to pass. Still dumb with astonishment, a bit awed, Rawley crossed the threshold and for the first time in his life stood in the presence of his grandfather.

A powerful figure the old man must have been in his youth. Old age had shrunk him, had sagged his shoulders and dried the flesh upon his bones; but years could not hide the breadth of those shoulders or change the length of those arms. His eyes were piercingly blue and his lips were firm under the drooping white mustache. His snow-white hair was heavy and lay upon his shoulders in natural waves that made it seem heavier than it really was,—just so he had probably worn it in the old, old days on the frontier. His eyebrows were domineering and jet black, and the whole rugged countenance betrayed the savage strength of the spirit that dwelt back of his eyes. But the great, gaunt body stopped short at the knees, and the gray blanket smoothed over his lap could not hide the tragic mutilation; nor could the great mustache conceal the bitter lines around his mouth.

“Back from Arizona, hey?” he launched abruptly at Rawley, and his voice was grim as his face.

Rawley started. Perhaps he expected a cracked, senile tone; it would have fitted better the tradition of the old man’s mental weakness.

“Just got back to-day, Grandfather.” Instinctively Rawley swung to a matter-of-fact manner, warding off his embarrassment over the amazing interview.

“Mining expert, hey? Know your business?”

“Well enough to be paid for working at it,” grinned Rawley, trying unsuccessfully to keep his eyes from straying curiously around the room filled with ancient trophies of a soldier’s life half a century before.

“Not much like your father! I’ll bet he couldn’t have told you the meaning of the words. Damned milksop. Bank clerk! Not a drop of King blood in his body—far as looks and actions went. Guess he thought gold grew on bushes, stamped with the date of the harvest!”

“I remember him vaguely. He never seemed well or strong,” Rawley defended his dead father.

“Never had the King make-up. Only weakling the Kings ever produced—and he had to be my son! Take a look at that picture on the bureau. That’s what I mean by King blood. Johnny, give him the picture.”

The Indian moved silently to a high chest of drawers against the farther wall and lifted from it an enlarged, framed photograph, evidently copied from an earlier crude effort of some pioneer in the art. He placed it reverently in Rawley’s hands and retreated to a respectful distance.

“Taken before I started out with Moorehead’s expedition in ’59. Six feet two in my bare feet, and not an ounce of soft flesh in my body. Not a man in the company I couldn’t throw. Johnny could tell you.” A note of pride had crept into the old man’s voice.

“I can see it, Grandfather. I—I’d give anything to have been with you in those days. Lord, what a physique!”

The fierce old eyes sparkled. The bony fingers gripped the arms of the wheel chair like steel claws.

“That’s the King blood. Give me two legs and I’d be a King yet, old as I am—instead of a hunk of meat in a wheel chair.”

“It’s the spirit that counts, Grandfather,” Rawley observed hearteningly, his eyes still on the picture but lifting now to the old man’s face. “The picture’s like you yet.”

The old man grunted doubtfully, his eyes fixed sharply upon Rawley’s face. His fingers drummed restlessly upon the arm of his chair, as if he were seeing in the young man his own care-free youth, and was yearning over it in secret. Indeed, as he stood there in the light of the old-fashioned lamp, Rawley King might have been mistaken for the original of the picture with the costume set fifty years ahead.

“Johnny, get the box.” Grandfather King spoke without taking his eyes off Rawley.

The old Indian slipped away. In a moment he returned with a square metal box which he placed on the old man’s knees. Rawley found himself wondering what his mother would say when he told her that Grandfather King had sent for him, was actually talking to him, giving him a glimpse of that sealed past of his. He watched his grandfather fit a key into the lock of the metal box.

“You’re a King, thank God. I’ve watched you grow. Six feet and over, and no water in your blood, by the looks. You’re like I was at your age. Johnny knows. He can remember how I looked when I had two legs. Here. You take these—they’re yours, and all the good you can get out of them. Read ’em both. Read ’em till you get the good that’s in ’em. If you’re a King, you’ll do it.”

He held out two worn little books. Rawley took them, eyeing them queerly. One was a Bible, the old-fashioned, leather-bound pocket size edition, with a metal clasp. The other book was smaller; a diary, evidently, with a leather band going around, the end slipping under a flap to hold it secure.

“I will—you bet!” Rawley made his voice as hearty as his puzzlement would permit. “Thanks, Grandfather.”

“I meant ’em for your father—but he wasn’t the man to get anything out of ’em worth while. A milksop—wore spectacles before he wore pants! His idea of success was to shove money out to other people through a grated window. Paugh! When he told me that was his ambition, I came near burning the books. Johnny could tell you. He stopped me—only time in his life he ever stuck his foot through the wheel of my chair and anchored me out of reach of the fire. Out of reach of my guns, too, or I’d have killed him maybe! Johnny said, ‘You wait. Maybe more Kings come—like Grandfather.’

“So I did wait, and after a while I could watch you grow—all King. I could tell by the set of your shoulders and the tone of your voice and the way you went straight at anything you wanted. So there’s your legacy, boy, from King, of the Mounted. Ask any of the old veterans who King, of the Mounted, was! You read those books.” He lifted a bony finger and pointed. “There’s a lot in that Bible—if you read it careful.”

“You bet, Grandfather!” Rawley undid the clasp and opened the book politely. The old man twisted his lips into a sardonic smile. His eyes gleamed, indigo blue, under his shaggy black brows. Then, as if reminded of something forgotten, he dipped into the box, fumbled a bit and held out his hand to Rawley.

“You’re a mining expert; maybe you can tell me where I picked them up.” His eyes bored into Rawley’s face.

Rawley bent his head over the three nuggets of gold. He weighed them in his hand, turned them to the light of the lamp which Johnny Buffalo had lifted from the table and held close.

“Greenhorns think that gold is gold,” Rawley grinned at last. “And so it is—but you left a little rock sticking to this one, Grandfather. So I’ll guess Nevada.”

“Hunh!” The old man’s eyes sparkled. “What part?”

Rawley glanced up at him with the endearing King smile. “Say, I’m liable to fall down on that! But I reckon King, of the Mounted, will put me flat against the wall before he quits, anyway. So—well, how about Searchlight?”

“Hunh! I guess you know your job.” The old man smiled back at him, a glimmer of that same endearing quality in the smile and the eyes. He waved back the gold when Rawley would have returned it. “Keep it—you’ve earned it. No use to me any more.” He settled deeper into the chair and gave a great sigh as his head dropped back against the cushions. “Fifty years ago I picked ’em up—and I’ve lived to see a King turn them over twice in his hand and tell me within a few miles of where I got them. That shows what I mean by King blood. Fifty years ago! It’s a long time to live like a hunk of meat. I’m seventy-nine—”

“Get out! You’d have to prove it, Grandfather. That’s a good ten years more than you look.”

“Don’t lie to me, boy.” But King, of the Mounted, failed to look censorious. “You read that Bible. Remember, that’s the legacy old King, of the Mounted, leaves to the next King in line. It don’t lie, boy. Read it faithful and heed what it says, and some day you’ll say the old man wasn’t so crazy after all.”

“Why, Grandfather,—”

But the old man waved him away with a peremptory gesture. Johnny Buffalo glided to the door, opened it and held it so, waiting with the inscrutable calm of his race.

“Well, good night, Grandfather. I’m—glad to have had this little talk. And I hope it won’t be the last. I always wanted to pioneer, and I’ve always felt as if I’d like to talk over those times—”

Rawley was finding it rather difficult even yet to bridge the silence of a lifetime.

“You grew up thinking I was crazy, most likely. Easy to say the old man’s touched in the head—when they don’t want to bother with a cripple. You’re a King. Maybe you can guess what it means to be a hulk in a wheel chair. And the Kings never ran after anybody; nor the Rawlinses, your grandmother’s people. Two good names—glad you carry ’em both. If you live up to ’em both you’ll go far. Take care of those two books, boy. Remember what I said—they’re your legacy from King, of the Mounted. Good night.”

The old man snapped out the last two words in a tone of finality and reached for his pipe. Johnny Buffalo opened the door an inch wider. Rawley obeyed the unspoken hint and straightway found himself outside, with the door closed behind him. He waited, listening, loth to go. Now that the feud was broken, he tingled with the desire to know more about his grandfather, more about those wonderful old fighting frontier days, more about King, of the Mounted.

“Crazy? I should say not!” Rawley muttered as he made his way slowly across the strip of grass by the syringas. “I only hope my brain will be as keen as Grandfather’s when I am his age.”

He stood for a few minutes breathing deep the night air saturated with perfume. Then, with the spell of his grandfather’s vivid personality strong upon him, he went in to where his mother sat gently rocking beside a rose-shaded lamp, looking over a late magazine.

“I’ve just been having a talk with Grandfather,” Rawley announced bluntly, sitting down opposite his mother and studying her as if she were a stranger to him. Indeed, those few minutes spent in the west wing had dealt a sharp blow to his unquestioning faith in his mother. Mrs. King dropped the magazine and opened her lips—artificially red—and gave a faint gasp.

“Grandfather’s mind is as clear as yours or mine,” Rawley stated challengingly. “A bit old-fashioned, maybe—a man couldn’t live in a wheel chair for fifty years or so, shut away from all companionship as he has been, and keep his ideas right up to the minute. If you ask me, I’ll say he’d make a corking old pal. Full of pep—or would be if he weren’t crippled. It’s a darned shame I never busted through the feud before. Why, fifty years ago he was all through Nevada—think of that! I’d give ten years of my life to have lived when he did, right at his elbow.”

He felt the sag in his pockets then and brought out the two little books.

“I always thought, Mother, that Grandfather King was a particularly wicked old party. Well, that’s all wrong—same as the idea that he’s weak in the head. He gave me this Bible, and made me promise to read it. He said—”

“Bible?” Rawley’s mother sat up sharply, and her mouth remained open, ready for further words which her mind seemed unable to formulate.

“You bet. He said if I read it faithfully and got all the good out of it there is in it, I’d thank him the rest of my life—or something like that. He meant it, too.”

“Why, Rawley King! Your grandfather has always been an atheist of the worst type! I’ve heard your father tell how he used to hear your grandfather blaspheme and curse God by the hour for making him a cripple. When he was a little boy—your father, I mean—he was deeply impressed by your grandmother asking every prayer-meeting night for the prayers of the church to soften her husband’s heart and turn his thoughts toward God. Your father has told me how he used to go home afterwards and watch to see if your grandfather’s heart was softened. But it never was—he got wickeder, if possible, and swore horribly at everything, nearly. Your father said he nearly lost faith in prayer. But he believed that the congregation never prayed as it should. I wouldn’t believe, Rawley, that your grandfather would have a Bible near him. Are you sure?”

“Here it is,” Rawley assured her, grinning. “He said it was my legacy from him.”

“Well, that proves to my mind he’s crazy,” his mother said grimly. “Your father always felt that Grandfather King had sinned against the Holy Ghost and couldn’t repent. Anyway,” she added resentfully, “that’s about all you’ll ever get from him. When he deeded this place to your father for a wedding present—that was a little while after your grandmother died—he reserved the west wing for himself as long as he lived. It’s in the deed that he’s not to be interfered with or molested. When he dies, the west wing becomes a part of this property—which is mine, of course. He lives on his pension, which just about keeps him and that awful old Indian. Of course the pension stops when he dies. So he was right about the legacy, at least. But I’ll bet he put a curse on the Bible before he gave it to you. It would be just like him.”

Rawley shook his head dissentingly. “It’s darned hard to sit in a wheel chair for fifty years,” he remarked somewhat irrelevantly. “I’d cuss things some, myself, I reckon.” And he added abruptly, “Say, Grandfather’s got the bluest eyes, Mother, I ever saw in a man’s head. I thought eyes faded with old age. Did you ever notice his eyes, Mother?”

His mother laughed unpleasantly. “Your Grandfather King never gave me any inducement to get close enough to see his eyes. Seeing him on the porch of the west wing is enough for me.”

“He laid a good deal of stress upon his past,” said Rawley. “I suppose because he hasn’t any present—and darned little future, I’m afraid. He gave me some nuggets. Would you like a nugget ring, Mother?”

His mother glanced at the nuggets and pushed away Rawley’s hand that held them cupped in the palm.

“No, I wouldn’t. Not if your Grandfather King had anything to do with it. He’s been like a poison plant in the yard ever since I came here, Rawley; like poison ivy, that you’re careful not to go near. I don’t want to touch anything belonging to him—and I hope I’m not a vindictive woman, either.”

Rawley was rolling the nuggets in his hand, staring at them abstractedly.

“It’s queer—the whole thing,” he said finally. “I feel a sort of leaning toward Grandfather. It was something in his eyes. You know, Mother, it must be darned tough to have both legs chopped off at the knees when you’re a young husky over six feet in your socks and full of pep. I—believe I can understand Grandfather King. ‘A hunk of meat in a wheel chair’—that’s what he called himself. And those amazing blue eyes of his—”

His mother glanced curiously into his face. “They can’t be any bluer than yours, Rawley,” she observed.

Rawley looked up from the nuggets, his forehead wrinkled with surprise.

“Oh, do you think that, Mother?” He stood up suddenly, still shaking the nuggets with a dull clink in his hand. “Well, I hope Grandfather’s passed on a few more of his traits to me. There’s a few of them I’m going to need,” he said drily and kissed his mother good night.

CHAPTER TWOJOHNNY BUFFALO BEARS ANOTHER MESSAGE

In his room, Rawley switched on the light and slid into the big chair by the table. Not to his mother could he confess how deeply those few minutes with Grandfather King had stirred him. In spite of her attitude toward the silent feud that had endured for nearly thirty years, he was conscious of the dull ache of remorse. Without meaning to judge his parents or to criticize their manner of handling a difficult situation, Rawley felt that night that he had been guilty of a great wrong toward his grandfather. He at least should have ignored the invisible wall that stood between the west wing and the rest of the house. He was a King; he should not have permitted that reasonless silence to endure through all these years.

As a matter of fact, Rawley’s life since he was twelve had been spent mostly away from home. First, a military academy in the suburbs of St. Louis, with the long hiking trips featured by the school through the summer vacations; after that, college,—with a special course in mineralogy. Since then, field work had claimed most of his time. Home had therefore been merely a place pleasantly tucked away in his memory, with a visit to his mother now and then between jobs.

The first twelve years of his life had thoroughly accustomed Rawley to the sight of the fierce old man with long hair and his legs cut off at his knees, who sometimes appeared in a wheel chair on a porch of the west wing, attended by an Indian who looked savage enough to scalp a little boy if he ventured too close; a ferocious Indian who scowled and wore his hair parted from forehead to neck and braided in two long braids over his shoulder, and who padded stealthily about the place in beautifully beaded moccasins and fringed buckskin leggings.

Nevertheless, there had been times, as he grew older, when Rawley had been tempted to invade the west wing and find out for himself just how bitterly his grandfather clung to the feud. It hurt him to think now of the old man’s isolation and of the interesting companionship he had cheated himself out of enjoying.

He pulled the two old books from his pocket, handling them as if they were the precious things his grandfather seemed to consider them. The Bible he opened first, undoing the old-fashioned clasp with his thumb and opening the book at the flyleaf. The inscription there was faded yet distinct on the yellowed paper. The sloping, careful handwriting of Rawley’s great-grandmother sending King, of the Mounted, forth upon his dangerous missions armed with the Word of God,—and hoping prayerfully, no doubt, that he would read and heed its precepts.

The date thrilled Rawley, aged twenty-six: 1858 was the year his great-grandmother had inscribed in the book. To Rawley it seemed almost as remote as the Stamp Act or the Mexican War. The thought that Grandfather King, away back in 1858, had been old enough to join the Missouri Mounted Volunteers—even to have been made a sergeant in his company and to make for himself a reputation as an Indian fighter—gave the old man a new dignity in the eyes of his grandson. It seemed strange that Grandfather King was still alive and could talk of those days.

The book itself was strangely contradictory in appearance. While the outside was worn and scuffed as if with much usage, the inside crackled faintly a protest against unaccustomed handling. The yellowed leaves clung together in layers which Rawley must carefully separate. Now and then a line or two showed faint penciled underscores; otherwise the book did not look as if it had been opened for many, many years. Nowhere was it thumbed and soiled by the frequent reading of a man living under canvas or the open sky.

“Looks to me like the old boy has simply passed the buck,” Rawley grinned. “Maybe he felt as if some one in the family ought to read it. His mother had it all marked for him, too; wanted to give him a good start-off, maybe. No, sir, the old book itself is pinning it onto King, of the Mounted! Mother must be right, after all, and Grandfather never had enough religion to talk about. But he sure gave me a Sunday-school talk; funny how a book can stand up and call you a liar.”

He smiled as he closed the book, whimsically shaking his head over the joke. Then, just to make sure that his guess was correct, Rawley opened the Bible again. No, there could be no mistake. Crackly new on the inside—though yellowed with age—badly worn on the outside, the book itself proclaimed the story of long carrying and little reading. The evidence against the sincerity of the old man’s pious admonitions was conclusive. Rawley laid the Bible down for a further consideration and took up the worn old diary.

Here, too, Grandfather King had betrayed a certain lack of sincerity. Reading the faded entries, Rawley decided that King, of the Mounted, must have been an impetuous youth who had learned caution with the years. Dates, arrivals, departures,—these remained. Incidents, however, had for the most part been neatly sliced out with a knife. And with a stubborn disregard for the opinion of later readers the stubs of the pages elided had been left to tell of the deliberate mutilation of the record. So Rawley read perfunctorily the dry record of obscure scouting trips, and the names of commanders long since dead and remembered only in the records.

Rawley learned that his grandfather had taken part in the making of much frontier history. He spoke of Captain Hunt in a matter-of-fact way and mentioned the date on which a certain Captain Hendley had been killed by Indians somewhere near Las Vegas, in Nevada. On the next page Rawley found this gruesome paragraph:

From a young Indian captured in the battle of last week, I learned the secret of the devilish poisoned arrows, which are black. The black arrows are poisoned in this manner, he tells me, and since I have befriended him in many small ways I do not doubt his word. To procure the poison, an animal is slain and the liver removed. A captured rattlesnake is then induced to strike the liver again and again, injecting all of its poison into the meat. The arrow-points are afterwards rubbed in the putrid mass and left to dry. Needless to say, a wound touched by this poison and decayed meat surely causes death. The young Indian tells me that a certain desert plant has been successfully used as an antidote, but he did not tell me the name of the plant. He declared that he did not know, that only the doctors of his tribe know that secret.

I think he lied. He was willing to tell me the horrid means of making the poison. But is too cunning to let me know the antidote. So the tobacco I’ve given him is after all wasted. The information merely increases my dread of the black arrows. Rattlesnake venom and putrid liver—paugh! I shall—

A page was missing. Followed several pages of brief entries, with long lapses of time between. Then came a page which gave a glimpse into that colorful life:

June, 1866. On board the “Esmeralda.” Arrived at El Dorado (Deuteronomy, 2:36) to-day. This is the first boat up the river.

The Scriptural reference had been inserted in very small writing above the name of the place. Evidently Grandfather King had been reading some Bible, if not the one his mother had given him.

A town has sprung up in the wilderness since I was here last, cursing the heat and stinging gnats in ’59. A stamp mill stands at the river’s edge and houses are scattered all up and down the river, while a ferry crosses to the other shore. A crowd came down to the landing for their mail and to see what strangers were on the boat. As yet I do not know whether our company will be stationed here or at Fort Callville, a few miles up the canyon. The Indians are quiet, they say. Too quiet, some of the miners think. On the edge of the crowd I saw a young squaw—or perhaps she is Spanish. She has the velvet eyes and the dark rose blooming in her cheeks, which speaks of Spanish blood. By God, she’s beautiful! Not more than sixteen and graceful as a fairy. I leaned over the rail—

Several pages were cut from the book just there, and Rawley swore to himself. When one is twenty-six one resents any interruption in a romance. The next entry read:

July 4th. Great doings at the fort to-day, with barbeque, wrestling, target practice and gambling. Miners and Indians came out of the hills to celebrate the holiday. In the wrestling matches I easily held my own, as in the sharp-shooting. Anita received my message and was here—el gusto de mi corazon. What a damned pity she’s not white! But she’s more Spanish than Indian, with her proud little ways and her light heart. Jess Cramer tried again to come between us, and there was a fight not down on the program. They carried him to the hospital. A little more and I’d have broken his back, the surgeon said. If he looks at her again—

More elision just when the interest was keenest. Rawley wanted to know more about Anita—“the joy of my heart”, as Grandfather had set it down in Spanish. The next page, however, whetted Rawley’s curiosity a bit more:

July 15th. To-morrow we march to Las Vegas to meet a party of emigrants and guard them to San Bernardino. The Indians are unsettled and traveling is not safe. A miner was murdered and scalped within ten miles of the fort the other day. No mi alebro—Anita wept and clung to me when I told her we had marching orders. Dulce corazon—God, how I wish she was white! But in any case I could not take her with me. I shall return in a month’s time—

August. In hospital, after a hellish trip in a wagon with other wounded. Mohave Indians attacked our wagon train, one hundred miles northeast of here, on the desert. While leading a charge afoot against the Indians I was shot through both legs. Gangrene set in before we could reach this place, and the doctor will not promise the speedy recovery I desire.

My Indian boy, Johnny Buffalo, refuses to leave my side. He hates all other whites. On the desert I picked him up half dead with thirst, and set him before me on the saddle because he feared the wagons. I judge him to be about ten. If I live, I shall keep the boy with me and train him for my body-servant. A faithful Indian is better than a watch-dog—

A lapse of several months intervened before the next entry. Then a brief record, which told of the closing of one romance and the beginning of another:

November 15th. This day I married Mary Jane Rawlins. Was able to stand during the ceremony, supported by two crutches. My Indian boy slipped away from the others and stood close behind me during the service, one hand clutching tightly my coat-tail. Mary has courage, to wish to marry a man likely to be a cripple the rest of his days.

Nothing further was recorded for several years; four, to be exact. Then:

Returned to-day from hospital. After all this suffering, both legs were taken off above the knee. The poison had spread to the joints. What a pity it was not my neck.

On the next page was one grim line:

December 4th, 1889. My wife, Mary Rawlins King, was buried to-day.

That ended the diary. In a memorandum pocket just inside the cover, a folded paper lay snug and flat. Rawley drew it forth eagerly and held it close to the lamp. His face clouded then with disappointment, for nothing was written on the paper save a list of Bible references.

So that was the legacy. An old diary just interesting enough to be tantalizing, with half the pages cut out; Bible references probably given to King, of the Mounted, by his mother. And a worn old Bible that had never been read. Rawley stacked the books one upon the other and leaned back in his chair, staring at them meditatively while he filled his pipe. He took three puffs before he laughed silently.

“He was a speedy old bird, I’ll say that much for him,” he told himself. “I’ll bet those pages he cut out fairly sizzled. And I’ll bet he cut them out about the time he married Grandmother. Also, I think he left one or two pages by mistake. Well, I’ll say he lived! As long as he had two good legs under him he was up and coming. I don’t suppose there’s a chance in the world of getting him to talk about Anita. ‘El gusto de mi corazon—’ There’s nothing like the Spanish for love-making words. And that was in July—and he married Grandmother in November. Poor little half-breed girl who should have been white! But then, I reckon he’d have gone back to her if he could. But they sent him home—crippled for life. You can’t blame Grandfather, after all. And I notice he mentioned the fact that Grandmother wanted to marry him. Sorry for the handsome young soldier on crutches, but it’s darned hard on Anita, just the same. And I don’t suppose he could even get word to her.”

He smoked the pipe out, his thoughts gone a-questing into the long ago, where the black arrows were dipped in loathsome poison, and young Indian girls had the fire and grace of the Spaniards.

“She’d be old, too, by now—if she’s alive,” he thought, as he knocked the ashes from his pipe and yawned. “I wonder if she ever forgot. And I wonder if Grandfather ever thinks of her now. He does, I’ll bet. Those terrible, blue eyes! They couldn’t forget.”

He went to bed, his imagination still held to the days of the fighting old frontier; still building adventures and romances for the dashing, blue-eyed King, of the Mounted.

He was dreaming of an Indian fight when a sharp tapping on his window woke him to gray dawn. He sprang out of bed, still knuckling the sleep out of his eyes, and saw Johnny Buffalo standing close to the open screen. The Indian raised a hand.

“You come quick. Your grandfather is dead.”

CHAPTER THREE“MY HEART IS DEAD”

It was the evening after the funeral, and Rawley was sitting again on the porch, staring out gloomily over a cold pipe into the yard. His grandfather’s death had hit him a harder blow than he would have thought possible. The shock of it, coming close on the heels of his first keen realization that Grandfather King was a vivid personality, left him numbed with a sense of loss.

His mother’s evident relief at the removal of an unpleasant problem chilled and irritated him. Her calm assumption that the Indian must also be removed from the place, now that his master was gone, seemed to Rawley almost like sacrilege. The place belonged to his mother only by right of his grandfather’s generosity. To rob the Indian of a home he had enjoyed since boyhood was unthinkable.