Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

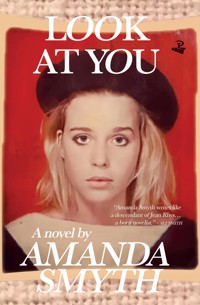

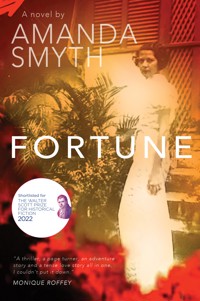

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Eddie Wade has recently returned from the US oilfields. He is determined to sink his own well and make his fortune in the 1920s Trinidad oil-rush. His sights are set on Sonny Chatterjee's failing cocoa estate, Kushi, where the ground is so full of oil you can put a stick in the ground and see it bubble up. When a fortuitous meeting with businessman Tito Fernandez brings Eddie the investor he desperately needs, the three men enter into a partnership. A friendship between Tito and Eddie begins that will change their lives forever, not least when the oil starts gushing. But their partnership also brings Eddie into contact with Ada, Tito's beautiful wife, and as much as they try, they cannot avoid the attraction they feel for each other. Fortune, based on true events, catches Trinidad at a moment of historical change whose consequences reverberate down to present concerns with climate change and environmental destruction. As a story of love and ambition, its focus is on individuals so enmeshed in their desires that they blindly enter the territory of classic Greek tragedy where actions always have consequences.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AMANDA SMYTH

FORTUNE

In memory of Kim Robinson

ONE

Somewhere between Gasparillo and Chaguanas on the Southern Main Road, Eddie felt the engine slipping and gasping as if catching its breath and every now and then he heard a pop-pop and he hoped it would hold out, at least until he got to Strong Man. But there it was, broken down with smoke gushing out of it. He knew it wasn’t gasoline and he knew he had water. The fan belt, maybe, or even the piston rings. No point looking under the bonnet until it cooled down.

He lit a cigarette, wondered how he could get a message to his uncle. A white sun punctured the sky, and there was a hard glare; some clouds low over the central hills. Not a good time to be stranded. No matter, somebody would come along at some point. He’d passed at least two cars heading this way, a buffalo cart full of coconuts and he’d almost stopped the old Indian man because his mouth was claggy, and then thought better of it. The cart would catch up eventually, unless the man had turned off the road already.

Glad of his hat, Eddie rolled down his sleeves and walked a little up the bank. A samaan tree offered some shade and from here he could see the direction he’d come from and think what to do. The land around was crispy and dry, hills scarred with black marks and drifts of pale smoke. He’d seen it too often, a bottle thrown, a careless cigarette, and next thing the whole hill was roasting like a side of meat. He spotted a brown dog with its belly bloated poking out of the grass. Just yesterday he’d hit a stray when it ran out into Coffee Street. He got out to check the bumper – surprised to find it there and hollering, its back leg jerking uncontrollably. Two children were playing marbles on the side of the road so he gave them each five cents for a soda and when they’d gone, not wanting it to suffer, he drove over the dog and crushed its head.

Eddie finished up his cigarette, and went back to the truck. He lifted up the bonnet and peered inside; nothing looked out of the ordinary. He checked the sky and saw vultures floating high like black stars. It occurred to him, it could actually be hours before anyone came by; he might as well set off on foot. He made his way down the other side and the road was blurred. From his hip flask he took a gulp of warm rum and it swooshed easily down his parched throat. He put his bag on his back, checked his watch and set out towards the capital. He’d be there by nightfall if he was lucky.

As he walked along the edge of the cane fields, his face poured with sweat, his feet were hot and swollen in his cracked boots. Cicadas were clacking and droning, a loud, unnatural, mechanical sound, as if something mighty was about to explode. And the thought came to him: none of this mattered, the heat, his thirst, the broken-down truck; what mattered was his meeting this morning with Sonny Chatterjee. He could hardly believe what he’d seen.

Over the years, rumours of black puddles appearing on the land had drawn oil men to Sonny Chatterjee’s estate. Buried deep in South Trinidad, Kushi was a cocoa plantation of fifty acres; it had belonged in the Chatterjee family since 1905. Seen pooling at the foot of a tree, swirling on the skin of the Godineau river, there was talk of oil running free like honey along the path to Sonny’s door. But Sonny Chatterjee had a reputation as a difficult and ignorant man. So far, no one had persuaded him to let them test the land, let alone drill on it.

Eddie had been watching it for a while now. The first time he turned up, Chatterjee shooed him away.

A week later, Eddie came back with a crate of pineapples.

‘You again?’

Chatterjee’s eyes were bleary from sleep.

‘Yes sir, there are things to talk about.’

‘I just wake up. You can’t see that?’

‘It won’t take long. But if you’d prefer, I’ll come back another time.’ Eddie left the crate on the ground, and went back to his truck.

A couple weeks later he returned. ‘I knew your father, Madoo,’ Eddie said, as he walked towards Chatterjee, sitting outside the house in his white dhoti. It was late afternoon. ‘My uncle owns Mon Repos.’

Chatterjee narrowed his eyes. ‘Which Madoo?’

‘Old man Madoo with the short foot.’

Eddie hadn’t forgotten the sight of Madoo’s crooked figure on horseback; one leg longer than the other, a birth defect. Some years ago, Eddie had heard that Madoo was electrocuted by a falling cable outside a pharmacy in San Fernando.

‘Your uncle own Mon Repos?’

‘I used to see your father when I was a boy, riding through fields of citrus shouting orders.’

‘That’s him,’ Chatterjee said. ‘He like to play boss,’ and he told Eddie how his father sailed from Calcutta to Trinidad on the Golden Fleece, then after years of working at Mon Repos, traded his return passage to India for $5, and a piece of land. He planted cocoa trees. He’d offered loans to the villagers with high interest rates. He’d made a small fortune.

Chatterjee put out his arms, ‘Bhap come here with nothing; he make all this.’

Eddie told Chatterjee how, like him, he’d lost his father; how it turned him quickly into a man.

‘When your father pass, you can’t stand in the shade.’

‘Yes,’ Chatterjee said. ‘You must walk in the hot sun.’

Eddie called in to see Chatterjee every couple of weeks. He made the excuse that he was visiting his uncle nearby. He brought oranges, or mangoes, or bananas; whatever was falling off the trees. Chatterjee didn’t thank him but he took what he brought. At first they stood by the truck and smoked a cigarette. Then after he had visited a few times, Eddie was invited to sit in the porch with the broken-down wall, where a warm breeze blew. They never ventured beyond here; the rest of the estate was out of bounds. Eddie was desperate to see it.

While they talked, Sita brought tea or juice, and she looked at Eddie from the sides of her eyes. She wore her hair in a plait, and her face was set, as if she had eaten something sour.

Eddie was sure that Chatterjee knew why he was there. Once he said, ‘If you come for oil, you may as well leave right now.’

Eddie kept quiet.

Chatterjee seemed exhausted; dark rings under his bloodshot eyes. He was only thirty-seven, but he looked twenty years older. Everything at Kushi looked tired. Walls needed paint, the yard was full of junk and there were buckets everywhere ready to catch rain when it fell.

Eddie asked, ‘You have water?’

‘We have tanks but no pump.’

Then Chatterjee told Eddie about the strange mushrooms he’d found clinging to the branches of his cocoa trees. He’d lopped off the diseased branches, cut away the rotten pods.

‘From Brazil to these islands, millions of cocoa trees are dying. It’s not just Kushi, Sonny. The whole of Trinidad is the same thing.’

‘They say put oil, sprinkle flour. Scorch the trunk until it black and they fall off. I try all that. I get on my knees and pray.’

Eddie wanted to tell Chatterjee: forget cocoa, it’s finished, but he figured Chatterjee wasn’t ready to hear it. He’d wait.

Then the moment came when Chatterjee asked Eddie what was inside the bag he always carried. Eddie opened up the cowhide satchel. He brought out a folder with papers, documents, photographs.

‘This, sir,’ Eddie said, picking through them, ‘is Beaumont, Texas. And this is where I once leased a piece of land, this land here with nothing on it.’ The photograph showed about an acre of grass and a small shed. Eddie was standing next to it alongside another man, their eyes squinting in the sun. ‘My partner, Michael Callaghan.’ There was another photograph of this same land with a tall structure, and a metal pick.

‘This cable tool, here, goes into the ground.’ Then, ‘This is what happened.’ Eddie held up the photograph.

Chatterjee leaned in, pointed to the black mark on the image.

‘That’s oil coming out of the ground. It’s called a gusher.’

Eddie had cuttings of newspapers showing pictures of cars, trucks.

‘It’s the future, Sonny.’

Chatterjee looked away at the early blue light sifting through the leaves of the immortelle. Mist hung in the bush giving the place a dreamy look.

‘Cocoa’s in serious trouble,’ Eddie told him. ‘You might save some of these trees, but chances are they’ll take years to produce. You have something much more valuable and you’re sitting right on it.’

‘So they tell me,’ Chatterjee said, lolling his head. ‘Apex, Texaco, Leaseholds, all of them. They say I could make a few dollars.’

‘I’m not talking about a few dollars. I’m talking plenty money.’ Eddie held his hand high from the ground.

‘Money to send your children abroad to study, buy yourself a new car; fix up your house. Buy your wife a diamond ring or a herd of cows. Pay a doctor when you need one. Apex won’t tell you how much money is under your feet because they want it for themselves.’

All the while Chatterjee looked into the darkness.

‘You understand? You’re not dealing with a person; you’re talking to a corporation. They don’t care about the small man. Believe me, Sonny, they’ll try to convince you that you’re a small man.’

He didn’t tell Chatterjee that just last week he’d been to see Charles Macleod – Apex’s senior operations manager, to talk about employment. Macleod had spoken of oil on Chatterjee’s estate. He’d called Chatterjee a ‘coolie fool’.

The pay was as good as anything else Eddie might find in Trinidad, but there was something about Macleod that made his skin bristle, the strange force of the man, his bloodless complexion, eyes twitchy like fleas. Could you dislike someone because his eyes twitched? It would seem so.

And while Eddie kept quiet about Macleod, Chatterjee didn’t tell Eddie that Charles Macleod had been to see him two days ago, and offered him a holding fee of $1000.

Eddie said, ‘I’ve learned something, Sonny, we must set our sights on the future. There’s no point looking back; we’re not going that way. Sometimes you have to destroy the old to make way for the new. If you want me to help you I can.’

Then, this morning, after months of visiting, Chatterjee took Eddie by surprise.

‘You have money to get started here at Kushi?’

Eddie looked at him. ‘I need to speak to some people. But yes, there’s money around. We can do some tests, take a look at what’s there.’

‘Why not see what you can do.’

Chatterjee walked Eddie back to his truck, where his boys were sitting in front, twisting the wheel, thin as sticks. He clapped his hands.

‘Sons, show Mister Eddie what you find.’

They jumped down and ran off towards the forest. For the first time, Eddie was taken deeper into the estate. He followed the boys along a trail through semi darkness.

Eddie saw how the cocoa trees were bowed and wilted and rotting. He could see their spores, the marble patterning on their trunks; there was a smell of rot. Parts of the estate were overgrown, evidence that Chatterjee had long since given up. They climbed through ferns; high silver shrubs stalked up; dangling vines low like trip wires. They picked their way through until they found a clearing.

One of the boys found a thin pipe, and taking a heavy stone, hammered the pipe into the ground. Eddie watched a spurt of black liquid spit up and make a puddle right there at his boots.

He bent down, rubbed it between his fingers and held it to his nose: Mary, mother of God, he said to himself. The land was saturated. He wanted to jump in the air, wash his face with it, hold Chatterjee and shake him. Instead, Eddie said, and his voice was calm, ‘Let me see what I can do. Give me a few days.’

‘Doh take too long,’ Chatterjee said, and for the first time in weeks, Eddie saw him smile, though there was a tightness around the man’s mouth that made smiling look painful. ‘I might change my mind.’

Eddie was thinking of all of this, and he pictured Chatterjee as he sat in his porch with his hands around his belly, looking out at the dark yard. And while fixing his eyes on the hazy road ahead, black and lumpy with new pitch, he felt in his bones and in his blood that his life was about to change. For months he’d been trying to figure out where he should be, looking for a direction. He’d found it this morning: yes, his fortune was no doubt buried right there in Siparia on Sonny Chatterjee’s estate. This was what he had been waiting for, and he was so lost in this thought with the brutal sun hitting his face that he didn’t hear Tito Fernandes’ horn hooting until he was right there beside him, the Ford Model T car gleaming like a Christmas bauble.

‘Hey,’ Tito said. ‘That was your truck?’ He pointed behind him. ‘They give a lot of trouble; I had one myself and got rid of it.’ Then he said, ‘Get in,’ reached over and pushed open the door.

‘Could be the belt,’ Eddie said, ‘I’ve felt it for a while, like a dog slipping a leash. If you could get me to a mechanic, I’ll be grateful. This place is like a desert.’

Tito smiled. ‘Everyone’s in church and those who aren’t probably should be.’ Then he put out his hand and they introduced themselves.

Eddie climbed in, ran his eyes over the leather interior.

‘Don’t ask,’ Tito rolled his eyes, ‘If you made me choose right now – my dear wife or my car, I’m not sure which I’d pick. I know which is less trouble.’

Eddie stuck a cigarette in his mouth, cradled a small flame. He tried to figure out if he’d seen Tito before; his face was familiar.

‘It’s the future,’ Eddie said. ‘One day the roads will be full of them. And they probably won’t look like this.’

‘You’ve seen the Tourer?’

‘Oh yes,’ Tito nodded, ‘in pictures. And the Bugatti. The Mercedes – a pretty, pretty car.’

On the left were rice fields and coconut trees. Tito accelerated along the Southern Main Road towards the Northern Range and the needle on the dial hit 46 miles an hour and it stayed and trembled there for five miles or so. The car rattled and shook; it felt like it was going fast because it was going fast. Eddie envied its thrust and power, especially after his slow drive that morning in Uncle Clyde’s truck. Not bad at all. He could do with something like this. Yes, when he had some money, he’d buy himself a new car.

‘Where you from, Eddie?’

Tito slowed down.

‘I was born here. But I’ve been living in America a few years now. California, Houston. All over, in fact. You can make things happen there. Chances are they’ve been done before. In Trinidad you can be the first, a pioneer. It’s hard to get things done. But you can make your mark.’

‘Is that what you want to do? Be a pioneer? Make your mark?’

‘Yes,’ Eddie said, and glanced at Tito, ‘in some ways. Don’t we all?’

‘Trinidad’s changed. There’s money, sure, but drive around at night, and people half-naked sleeping on the streets of Port of Spain. They say trouble coming again.’

‘Strikes?’

‘Push people down long enough and they come back harder. The British ’fraid the blacks, they ’fraid Indians, now, too. They tell the government, send troops! Send marines!’ Tito put his fist in the air. ‘People done with poor wages, long hours. You can’t blame them. But Cipriani changing things.’

‘You like him?’

‘Yes, I like how he’s a racehorse trainer, a Captain in the army and he’s a champion of the barefoot man! They love him because he speaks for the poor. If they don’t listen to him, there’ll be much more radical leaders coming up. But who knows, he’s a colonial, they might turn on him, too. Trinidad not easy.’ Then Tito said, ‘My wife talks about emigrating. I tell her yes, sure, let’s go to America, give it a try. But Trinidad is home; I never leaving here.’

Tito winked at Eddie, and accelerated towards the south quay where the sun was low and yellow as a yolk. A cruise ship was sailing into the wharf, Benediction, in silver letters along the starboard, probably from New York, taking a tour of the islands. By the gate, a small crowd of locals waited. A young black woman posed with a macaw on each shoulder: something for the tourists. As the ship docked, passengers would drop dimes in the water and watch the local boys dive down to find them. Eddie had seen it time and time again – all up the islands, and he didn’t much like it.

The sky was softening now above the new railway station with its arched windows and impressive pavilions. Trains ran regularly from here to San Fernando, out to Sangre Grande, too. He’d heard complaints – the building was a colossal waste of money, unnecessarily ostentatious, especially now trams and automobiles were proving more efficient and cost effective. Good news for oil; good news for Eddie.

‘You have a wife, Eddie?

‘Not yet, I want to make my fortune first.’

‘Don’t wait ’til you’re an old man like me. I was lucky to find Ada.’

‘Love at first sight?’

‘Yes, for one of us at least. We’re a team. Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks.’

‘What’s the secret?’

‘Twice a week we go out for a candlelight dinner. Ada goes Tuesdays and I go on Fridays.’

Eddie grinned.

‘You don’t fight?’

‘Yes we fight. About where we go on holiday. I say I want to go to Paris, and she says she wants to come with me.’

Tito was feeling better, thanks to his new companion.

Around the savannah horses were cantering, their bodies shining in the dipping sunlight; clouds of dust, red as cinnamon, puffed out behind their legs.

Eddie thought about his uncle. He should get a message to him.

Tito rolled into the driveway at the Queens Park Hotel.

‘Let’s get something to drink before we both pass out. Something strong. I’ve had a long day. Maybe I’ll tell you about it some time.’

‘You sure I’m dressed right? I have another shirt in my bag, though it’s creased up.’

‘Don’t worry, you’re with me. I have shares in this place.’

They parked and walked through the lobby to a long bar: wooden shutters leaned out into a garden, sprigs of bougainvillea on the tables; a woman in a long gown was playing the piano. Behind the bar, a young black man stood to attention in a bow tie and flashed his china-white teeth.

‘Mister Fernandes. How are you?’

‘Thirsty like a donkey in the desert, but apart from that I’m alive.’

‘Glad to hear it,’ the man said, and he nodded at Eddie.

Tito ordered a half bottle of gin and a jug of coconut water. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘we’ll drink a little, and then head back and sort out your vehicle. A man needs refreshments in this heat. I keep telling my wife, you worry about vitamins but you must never forget to hydrate. Especially in this hell hole.’

He smiled and his fleshy cheeks dimpled like doughnuts.

They found a table by the window and away from the bar. There was a kind of splendour here that Eddie had forgotten about – the polished wooden floor, modern overhead fans and starched tablecloths. This was a place for wealthy white Trinidadians, French Creoles, and American tourists. Eddie knew of the hotel, but he’d never had a reason to step inside. He should wash his hands.

Tito said, ‘So what’s your business?’ Then, ‘Let me guess, you’re a planter.’

‘Not quite,’ Eddie said, ‘I get bored; agriculture’s not for me. Everything takes too long. I like to move around.’

‘Construction?’

‘Closer. I’m a driller.’

Tito cocked his head. ‘Okay. That fits. You can’t be short of work.’

‘There’s plenty to choose from.’

While the light changed and hotel guests came and went, Eddie and Tito emptied the bottle of gin and jug of coconut water and when it ran out, Tito called for more. The cook sent slices of pork and peppered shrimps, and hot bread. Eddie hadn’t realised how hungry he was until he started eating. While they ate and drank, Eddie told Tito about his Uncle Clyde, and how he’d come back to Trinidad to help him up at Mon Repos Estate.

He spoke about his good friend Michael Callaghan and their search for oil in New Mexico. Their near success in Beaumont, and how they were scuppered by the owner of the land who turned out to be the biggest crook since Al Capone. He explained how he’d got caught up in the Teapot Dome in Wyoming, found the site on the edge of a football pitch and drilled down with a cable tool, and a pump. He and Callaghan had drilled the patch for five weeks. The well came in at 550 feet, one of the largest wells in history. Meanwhile, in New York, the owner was subpoenaed on four counts of bribery and corruption. He had no choice but to walk away without a cent. His nose was keen; he’d been unlucky. He’d learned his lessons. He wouldn’t make the same mistake twice.

Eddie found himself telling Tito about his father, who had died in a volcano in St Vincent.

‘They tell me he was on the mountainside when a stone fell next to him. Then the stones fell thicker, one or two were big, too big to be thrown by anyone’s hands. Then he must have seen it was the mountain – pitching stones at him. He ran towards the sea bawling for help, ash and steam pouring out. Lava trickled down and buried the crops and houses. The volcano came like that, and no one knew. It spewed for days.’

He explained how his mother died soon after because her big heart was torn right out of her and there was nothing inside to keep her alive. At fifty-five years old, she fell asleep one evening and didn’t wake up.

It occurred to Eddie that he was talking to Tito like he hadn’t talked to anyone in years. It felt good, like putting down a heavy suitcase he’d been carrying.

‘Mother was full of tears. Nothing worse than dying when you’re alive. I’m glad in some ways she’s gone.’

As he said it, Eddie knew it wasn’t true. A day didn’t pass when he didn’t think about his mother.

Tito listened and nodded. ‘Dying while you’re alive is a terrible thing. A lot of people live like that.’ He told Eddie he was brave. ‘You’re a fighter, you’ll do okay. Most people live their lives like a sentence; you know what you want. I’m sure you’ll get it.’

‘I know what I want – I died twice.’

‘You died how?’

‘Malaria when I was eight. Then my plane crashed in Carcassonne. I saw angels come around.’

‘Angels?’

‘I don’t know what they were but I figured they were angels by the light they brought. I thought that was the end. Everyone was dying. It was the war.’

‘Were you afraid?’

‘Of what, angels?’ Eddie laughed. He took out another cigarette and lit it. ‘I’m still here; there’s no time to be afraid.’

‘I like to think I have time.’ Tito leaned back in his chair. ‘There’s nothing wrong with a little self-denial. I’d rather glance at things from the sidelines.’

‘Sure, each to his own. It’s just a different view.’

Tito raised his glass. ‘To the angels.’

By now the air was thick and still. The waiter pushed back the shutters and there was a little breeze and Eddie saw that evening had come. Fireflies glittered in the darkness; he had never seen so many at once. His head was tight, and he felt good in himself. He felt a new charge and it wasn’t just the liquor. He called through a message to his uncle; he would try to be there by lunchtime. He didn’t mention the truck; he would pick that up tomorrow. Tonight he would stay in Rattan’s hotel – it was cheap, familiar, a little on the rough side.

‘I know Rattans. My low-life brother used to stay there; it’s where all his friends hang out. He’s another story altogether. I’ll save that for next time.’

Tito apologised, he hadn’t meant to keep him back. ‘We could go and get my mechanic right now, he’s there in Belmont.’

‘No sir,’ Eddie said, ‘it can wait.’

Music started up. The song was a familiar, lively tune and a couple got up and started to dance, a slow, quick-quick step. They probably imagined they looked like film stars; their eyes never left each other.

‘Love like dove,’ Tito said.

Then, heady with liquor, Eddie was saying, ‘There’s a man called Chatterjee, he owns a big cocoa estate down in Siparia. It’s full of oil.’

‘All down there has oil – Fyzabad, Brighton, Point Fortin.’

‘This is different. Chatterjee’s place is floating on it. You can smell it in the air.’

‘It’s one thing to have it on your land; getting it out is another thing altogether.’

‘No sir, not at all. Look at those twin brothers in Los Angeles – the Applegates; they drilled on the corner of Glendale Boulevard and Harman Drive using the sharp end of a eucalyptus tree. Two years later they have eighty wells and they’re millionaires.’ Eddie leaned in, ‘Chatterjee’s oil is so near the surface you could suck it up with a straw.’

‘Then why doesn’t he?’

‘Because he doesn’t know how. He only knows how to farm and his cocoa trees are dying.’

Eddie pulled on his cigarette, swirled the smoke around his mouth and blew it out.

‘So how come Apex not in there?’

‘Apex come and hassle Chatterjee to lease the land. Chatterjee says no.’

‘Why?’

‘Who knows? Macleod, the manager, has the charm of a cockroach. Maybe Chatterjee can’t stand colonials. He doesn’t want them on his land. Maybe he’s honouring his father. He came on a boat from Calcutta fifty years ago and made something of himself. Chatterjee might not have any business sense, but he doesn’t want foreigners. He prefers dealing with the ordinary man.’

‘An ordinary man like you.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘So you want him to let you drill?”

‘Of course.’

‘And why would he let you but not Apex?’

‘Because I give a better rate. They only want to lease the land for a small fixed fee. I offer a percentage. I wouldn’t need more than a dozen men. I’d treat his land with respect and keep costs low. I’ll make money – money for me, money for him. I’ll turn us into millionaires.’

Tito nodded. He looked impressed. ‘Have you spoken to him?’

‘When you picked me up, I was on my way back from his house.’

‘In Siparia?’

‘I drove down there last night and met with him.’

‘And what did he say?’

‘If I can get the money, he’ll consider it.’

‘Then you can buy your Bugatti.’

‘And find me a wife.’

Eddie laughed and Tito laughed, a deep huwah-huwah that came from low in his belly. They drained their glasses and Tito called for brandy.

‘I should go. I don’t want to get you in trouble.’

‘Yes,’ Tito said, ‘but I’m already in trouble. She knows where I am. I haven’t laughed like this in a while. I’ve had a tough day, another time I might tell you about it.’

By now the girl on the piano had left, and the bar was filling up with a new crowd: visitors from the cruise ship, Americans, the beautiful people. They looked like they were enjoying themselves, as was Eddie. It had been a long time since he’d kicked back and spent time in a place like this. Not since he was in New York with Callaghan. He could get used to it.

‘So how much do you need?’ Tito leaned in, looked straight at Eddie. ‘Name a figure.’

‘Around ten thousand dollars, I guess, initially, to clear the forest, bring in water, build roads, equipment. It doesn’t have to be new. I can make do.’

‘Maybe I can help.’ Tito’s eyes held steady. ‘Maybe I could find some money for you. Enough to get you started. We should talk.’

Tito got up and went to the bar to pay the bill; short and blocky from behind; a solid little man. Eddie wondered how drunk he was. They’d been here since after four and it was gone midnight. The last couple hours they’d slowed down, and Eddie was tired now, not drunk. But then he could take his liquor. He barely knew Tito Fernandes but he, too, seemed sober enough.

‘Look,’ Tito said, putting on his hat, feeling that he needed to lie down. ‘We’re having a party at my house on Saturday, why don’t you come? You can meet my wife. There’ll be music; the great and good will be there. We can talk some more if you wish.’

‘Sure,’ Eddie said. ‘I’d like that.’

‘Come as you are. You’ll be a novelty with the ladies. Now, if you don’t mind, you can drop me home and bring my car back on Saturday. In the meantime I can walk to the office.’ He patted his chest. ‘My wife tells me it’s good for my ticker.’

Outside, the moon was low and full. Eddie drove Tito back to his home in Broom Street, and took in the pale, brightly lit house, with a curved driveway in front and on either side of the gateposts two large sculptures that reminded him of figures he had seen in the Tuileries, in Paris. The front door was open, and he watched Tito walk slowly up the steps to the entrance where a woman appeared in a white dressing gown, and put her arm around him.

The woman was striking, with dark hair pinned up, and in the strange moonlight her face took the shape of a locket, oval, shining. Her mouth was wide like a singer’s, dark eyes reaching – trying to see who he was.

‘See you Saturday!’ Tito bellowed above the engine. ‘8 pm.’

Eddie caught himself, waved goodbye, and drove off into the night.

TWO

‘Why is that man taking our car?’

‘That man, my beloved, is Eddie Wade and we’re going to do business together. You will like him.’

‘Eddie who? Why does he have our car? How can you let him take it?’

They watched the car disappear into the night, then Tito and Ada went inside. They climbed the dark stairs to the top of the landing and a long corridor. She could now see that Tito was drunk. More stairs. He complained the house was full of stairs. Outside their bedroom, he caught his breath before a painting of his mother. Her collar was high around her throat, eyes like two holes.

‘She looks sour, don’t you think? I don’t like sour women. I’m so glad you’re not sour.’

‘Not yet,’ Ada said. ‘I’m getting more sour by the day.’

Tito wasn’t listening. He hummed to himself while he shuffled into the bedroom and started to unbutton his shirt; his fingers were too thick. A lamp threw soft light around the walls; the shutters were still open, the fan whirring and blowing out the lace drapes. Ada was wearing a white nightdress with embroidery on the cuffs and collar. Tito narrowed his eyes to bring her into focus. She looked young – a girl, with too much beauty.

‘Don’t break my heart, Ada.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Break my bones instead. I have 206 of them.’

Ada shook her head, knowing it was pointless to argue.

‘You have all your years ahead of you. Not like me.’

Now he sat on the side of the bed and tugged at his shoes, apparently glued to his feet. He pulled at his tie until it came loose and then rolled back on the mattress. He patted the little hill of his stomach. It had been giving him trouble of late, and he had a sour taste in his mouth. He groaned like an old man.

‘Help me, darling. This damn shirt.’

Irritable, Ada reached over and popped the buttons.

‘How’s my Flora?’

‘Sleeping. Don’t wake her.’

Tito got up and hefted himself out into the corridor, across the passageway into Flora’s room where her light was still on. She had never liked the dark. Just last week, she said she’d seen a skeleton leaning over her, half covered by a cloak and carrying a cutlass. She had run to her parent’s room and jumped in bed between them. She had seen death. Death was coming to them. It had taken them the best part of an hour to get her back to sleep.

Now she was curled up on her bed with her hair over her face. Tito plucked away the dark strands from her sticky mouth. She was breathing deeply, her cheek round and smooth like a gold peach.

‘Tito, how much you drank?’ Ada stood in the doorway, her face pale. ‘I don’t know what’s happening to you.’ She steered him back to their bedroom. ‘These days you disappear into your own world. You don’t care about anyone but yourself. You’re drinking too much. You reek of liquor. It was rum you drank?’

He fell back on the bed.

‘Gin. But not so much darling; not so much.’

‘You were at the hotel? Who’s this Eddie?’

‘Our lucky star. All will be revealed.’

‘My god, Tito! Why do you have to be so mysterious?’

She told him that she was not his mother, that she was tired of his late night gallivanting. If he thought he could wake her in the night like his father used to wake his mother at some ungodly hour, he could think again. Didn’t he realise she was worried? Flora was worried; Aunt Bessie was worried.

‘Remember how your father used to come home at all hours, wake your mother and tell her to find a chicken in the yard, slit its throat and cook it for him? You’re turning into your father.’

Ada pulled at his trousers, eventually giving up and flopping down on the bed beside him with a loud, exasperated sigh.

Tito closed his eyes, relieved the day was over.

That same Sunday morning, after he’d said goodbye to Ada and Flora, he had driven out of town towards the east, passed the turning to St Joseph – where he’d told Ada he had urgent business. He’d made his way along the empty road feeling wretched. As the land rushed by – the cane fields and rice fields and the beautiful hills with their black scars and the lilac sky above them – he wondered how he was going to dig himself out of the hole he was in.

He had lost half of the family fortune in the New York stock market. He had more than $50,000 saved in a high interest account in the Bank of the United States, which, according to the press, was preparing to announce its closure. The Hoover administration and The Federal Reserve were doing nothing to slow the rate of bank failures all over America and Alfie Mendes, his accountant, had warned Tito not to invest any more. He’d never foreseen the fall of Caldwell. How could he? But worse, he had taken a loan against his business to invest in a bank in Tennessee that had collapsed last week. The family stores were in jeopardy. He couldn’t face telling Ada.

Alfie told him he’d been lucky. There were men in New York who’d lost everything in one afternoon, hurling themselves from the tops of buildings.

‘But what do I tell Ada?’

‘Tell her the truth. Talk to her.’

‘She’ll be furious.’

‘Not as furious as if she hears it from someone else.’

While Tito drove along the road lined with coconut trees, their branches tossing like hair in the wind, he wondered if he might have done better elsewhere? England? America? Europe? Perhaps. But with a lump in his throat, he thought of how much he loved this island. He could never have lived anywhere else.

He remembered with some sadness how at five years old he’d cried when he saw a skin of a tiger stretched out on the wooden floor of a house in Surrey, England. The lady of the house asked, ‘Are you crying because of the tiger?’

Yes, he said, not because it was dead, but because it looked like a map of Trinidad. She took pity on him, went to the library and pulled down an atlas and she found the page featuring the British West Indies; the islands were scattered there in pastels against the blue of sea.

She said, ‘I see what you mean. A tiger skin. Be glad that you love your country so.’

As he’d headed towards Manzanilla, Tito imagined himself driving along the tiger’s belly, and as he felt the hot breeze blowing through the window he remembered how, in England, he’d never felt warm. No matter how many vests and sweaters he wore and how he positioned himself by the open fire in the great hall, his bones were always trembling. He traded baths with other boys, so he could soak in hot water three or four times a week. He lost weight. School meals made him sick; he survived on tins of mandarin oranges, slurps of condensed milk. Every morning, longing for the crabby hand of his mother’s writing, he looked for letters from home, watched for a coral stamp showing Blue Basin and an airmail sticker. He waited for summer to come, not realising his mother had other plans for him: seven years at The Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin.

Tito hadn’t cared for anatomical lectures, the minutiae of the human body and its illnesses. Clinical investigations and post mortems held no interest for him. He learned that to tug off the top of someone’s skull you needed a bone saw and some force; tearing through the thin layers of tissue covering the muscles and internal organs wasn’t always easy. He had learned how to make a button hole in the skin to hook your finger through and peel it away. The skin on the back peels beautifully, his lecturer said, because of glutinous fat beneath the surface.

Tito was mostly bored, his interest held only by the cardiology lectures. He’d found himself enthralled by the heart and its workings, its 100, 000 beats a day, the effortless pumping of blood around the body. He liked the idea of chambers, like rooms in a house and the blood’s journey through capillaries, arteries, returning through veins and venules, like rivers, streams and roads and tracks. The heart was the centre of man, where his soul’s fire burned. It needed to be tended. If its pathways were stretched and laid out, they would travel the earth twice. The enormous world of the heart! He’d asked his lecturer, was it possible the heart could actually be broken? Why yes, of course. Heartbreak could inflict damage like the blow of an axe. The heart can become diseased, rotten, an overworked thing of hardened muscle, a rock. He’d felt one in his hands – the enlarged grey heart of a woman brought from the psychiatric unit, who’d killed herself after more than fifty attempts.

Finally when he’d sailed home to Trinidad – his studies cut short by a bronchial infection in an appalling winter when Dublin’s little houses on the outskirts vanished beneath drifts of snow – Tito was twenty-five years old. As the steamer approached the Dragon’s Mouth, he watched the sea narrow itself between the four islands, like stepping stones along the twelve mile passage, and when he saw the tall black and copper cliffs and young palms along them blowing in the warm breeze, he felt his heart open. At Scotland Bay the sea was tourmaline and it seemed to him the pointed hills were awash with gold and he began to cry with joy.

His mother and father met him at the port, his father in his familiar white suit, his mother as tidy and neat as a new doll. At once, he saw the disappointment in his mother’s face, and he knew that he had failed her. Long before they reached home she was asking what was he going to do? If he thought he could come home and lie around the place, he could think again.

It had been, Tito believed, the right time to come back. Recent trouble in Port of Spain over the installation of proposed water meters had caused unrest. Protesters had gathered outside the Red House and pelted it with stones and rioters poured inside and set fire to stacks of papers. The governor had to be rushed to safety at police headquarters. A young woman, Eva Carvalho, was shot at point-blank range by a policeman who was said to be her estranged lover, while twelve-year-old Eliza Bunting was bayoneted through the chest. Victor Fernandes had been caught up in this fray on his way home. He was left badly shaken, a deep gash to his head from a broken bottle. Tito had told himself, now more than ever, his family needed him.

Victor Fernandes had given his son an apron and set him to work in the store. Fernandes Bazaar was 600 square feet with floor to ceiling windows, a room at the back where cocoa growers brought beans in exchange for goods. Tito was assigned to the storeroom upstairs to count stock. He took it upon himself to thoroughly clean the room and reorganise stock in a way that made it possible to see their quantities at once. He grouped goods by their type rather than use. He labelled every shelf and noted every item. He quickly understood how inefficient inventory led to financial loss; time spent looking for this or that was wasted time. All unusable items – out of date, or broken – were removed. Seasonal decorations were taken away and stored off site. Victor was astonished by his son’s initiative.

Tito was popular with customers, his dark eyes warm and brown as brandy. He’d say, Is there anything else I can do for you? Have a wonderful day, Do come back and see us soon. He remembered names, ‘Yes, Mrs Tibbits, can I put your bags behind the counter while you carry on shopping.’ ‘Hello Mrs Robinson, and how is your son today?’ ‘Red suits you very well, Mrs Davies.’ He persuaded his father to offer refreshments to thirsty shoppers.

‘We must make them feel cared for,’ he said. ‘Water the plants and watch them grow.’

He had filed, collated, and chased ledgers, often until late at night. In his lunch hour, he’d visited other department stores for ideas, or scoured the financial pages of the Daily Star. He encouraged his father to discount goods, and enable customers to purchase on high interest instalment plans. In those early days, Victor Fernandes imported goods mainly from Madeira – onions, the most succulent and nutritious beans, peas, garlic, wine, lace, tiles, biscuits. Tito persuaded his father to broaden their range. Why not bring in clothes? Or sell shoes? The same ladies who shopped for cookies needed to buy shoes and dresses and toys for their children. Don’t send them to Bata or Millers. Couldn’t his father see how Port of Spain was changing?

Tito found a supplier of fine leather ladies and gents shoes in New York. He told his father, ‘The secret was that they must fit the shoe to the foot not the foot to the shoe.’ He sought out fabrics through an old school friend in England, whose father and mother now lived in Bandra, Bombay. With their help, he imported silks and linens, silver and brass ornaments. Spices and herbs came from Europe, along with champagne and fine wines. He’d brought ice machines into the city to sell to restaurants and bars. He’d purchased a stainless steel industrial pasta machine, and with Canadian flour, made the best spaghetti in Trinidad. He’d set up a five star hotel – right there in Marine Square. Now there was scarcely any important city in the world that Fernandes and Co did not import goods from.

Tito had located a large warehouse in the west of Port of Spain and refurbished the stockroom to make a second shop floor and installed a lift. His father complained when he saw the accounts: they were spending money as fast as it was coming in. But for all his complaining, it seemed to Tito that his father’s protestations were half-hearted. The store was the busiest in Frederick Street: a new sign went up: Fernandes and Co – Something for Everyone.

Throughout these years, Tito had never grown tired of Trinidad, of the low skies, the dust or the choking heat, or rains when they came. Every morning, after he parked his car, he walked to his office in Frederick Street, stopped for coffee at the Hotel de Paris on Abercrombie, while puffing on his Anchor cigarettes. People would say, ‘Good morning Mister Fernandes,’ or ‘Good day, Tito!’ He’d watched friends emigrate to America or Europe. Tito would say, ‘Where you running to? There’s nowhere like Trinidad. You’ll only go to come back.’

In the evenings, on his way home, he’d drive around the Savannah, looking out at the lights and it seemed the grassland was a lake and he could almost imagine boats upon it. He glanced at the hills behind, dense with trees and bush, and he felt a rightness about his life, as if where he had meant to go was exactly where he had been. And it often came upon him, like a fact, as it did now, that this was the country where he would live and where he would die. This dense green land with its woodland and rivers and mountains and sprawling beaches was his home.

That Sunday morning, after driving for more than two hours, Tito had pulled into the grassy lay-by, then swerved onto a narrow trail that he knew took him to the beach. He saw the tide was out and sand was pale as flour. There was no one there. It wasn’t the time of year for holidaymakers. Just as well. He parked in the shade of an almond tree, turned off the engine, and found a driftwood log to sit on. He looked out at the foamy frills on the waves, and stared far out where the sea met the sky and found it difficult to see a separation between the two. Blue and more blue. The sun was not yet high. He loosened his tie, undid the top button of his shirt, and took a deep breath. He felt a little shudder in his body, as if he was letting go of something. There was a slight breeze and he could smell the sea’s salty breath. He thought about Flora and Ada and felt his heart lift with love for them. They were a part of his heart walking around in the world. He loved them more than anything; he knew he had a tendency for heaviness, and Ada could always raise his spirits. But these days he couldn’t find it in himself to make love to her. She deserved better; she deserved more.

He thought of the woman he’d almost married before Ada; she came to him like a photograph – Matilda Mendonca, daughter of a friend of his father’s, a devoted Catholic. She had jilted him two weeks before their wedding for Carlos Acevedo, a younger man, an overseer on a sugar estate. He’d been beside himself. He’d known the cost of this emotional pain to the heart: a high risk of arterial fibrillation, erratic blood flow leading to an early, and often, sudden death.

For a year, Tito kept their wedding cake in an icebox and cut himself a slice every day to eat with his afternoon coffee. Some days he ate two wedges of the fruity, layered cake encrusted with marzipan and a delicious citrus icing. Eating the cake was a comfort. This was how he started putting on weight. It was because of Matilda and Carlos. Over that year, he convinced himself that Matilda Mendonca and Carlos Acevedo had ruined his life forever.

His brother told him he should do something, teach Carlos a little lesson, rough him up. It would make him feel better; help to quell the pain. Raul knew people who could help. Why should you suffer, he said. Let them suffer instead.

Eventually, Tito gave Raul $500 and told him to take care of it. Six weeks later, Carlos Acevedo was found beaten to death outside a rum shop on the road to Roseau, Dominica.

Then he’d met Ada – at the Country Club Old Year’s ball – grown up and dazzling, dressed as the Queen of Diamonds. He had known her as a child but now she was different. He was struck by her brightness, her humour, all of the fifty-two moles he counted on her creamy skin. He courted her over a period of months. She swore to him that she would honour and cherish him; he knew that he could trust her. His beloved Ada.

To the beach, to the trees, to the vast sky, Tito had spoken her name aloud, ‘Ada.’ For the first time since his father died, Tito allowed himself to cry; big heaving sobs from his guts. He wondered in that moment if his financial loss was punishment from God for what he’d done to Carlos. Yes, perhaps, God was punishing him. He deserved it. He deserved to suffer. This thought made him cry more.

By then the sun was high, the sea a hard silver strip. He could fill his pockets with stones, and walk out into the water. Swim as far as he could. He would soon tire, hope for a rip tide to carry him out. The Atlantic was agitated at this time of year and it would quickly pull him down. What was he waiting for? He deserved to die; he had killed a man. Not with his own hands, but by his might.

Then he saw something. At first he couldn’t figure it out. A buffalo? A cow? No, this was something else. A horse, as pale as a ghost was standing at the water’s edge dipping its head. It was unusual to see a horse here on the beach. Still for a moment, it started to walk in his direction. Its mane was white, the pale legs lanky and young, a palomino. A palomino at Manzanilla. The horse had raised its nose as if smelling something in the air, smelling him, perhaps. Tito had always loved horses. He remembered from school: The air of heaven is that which blows between a horse’s ears.

He walked towards it, sand falling over his leather shoes, the sun burning his watery eyes.

‘Come,’ he said, through his tears, and he put out his hand.

The horse approached him, moving quicker now, swishing its tail of white ribbons, flicking its long mane, its hooves quiet and quick on the soft beach. It stopped in front of him, shoved its soggy nose into his palm and he ran his fingers along its golden forehead; stroked the curve of cheek. Its dark eyes were shiny and seemed to hold the world inside them. Had it escaped from a nearby farm? To whom did it belong? It was well looked after. He remembered peppermints in his cotton jacket, and the horse crunched through them. ‘You like that; you like sweets, eh.’ After a few minutes, the horse glanced back alert to something further down the bay. Then it flicked its head and turned from him. Tito watched it trot back along the beach until it became small. Just before it disappeared into the hazy light, it glanced back at him, then carried on. He felt something inside him shift. What was the horse doing here? Had it come to tell him something? He wondered for a moment if it was real. A vision. A symbol of hope.

He looked up to the sky. ‘God, if this is a sign, then help me climb out of the disaster I have made for myself.’

He’d got back in his car, and started for home, his mind strangely clear, blank as a fresh sheet of paper. He drove through the village of Mayaro, and through the streets of Princess Town and back along the Southern Main Road towards Port of Spain. About an hour later he saw a truck broken down on the side of the road next to a huge samaan tree. Further along this same road, a man was walking alone. That man was Eddie Wade.