Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

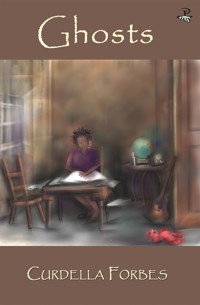

The circumstances of their brother's violent death inflicts such a wound on his family that its four oldest sisters feel compelled to come together to write, tell or imagine what led up to it, to unravel conflicting versions for the benefit of the younger generation of the huge Pointy-Morris clan. From the richly distinctive voices of the writer Micheline (Mitch), who could never tell a straight truth, the self-contained and sceptical Beatrice (B), the visionary and prophetic Evangeline (Vangie), and the severely practical Cynthia (Peaches), the novel builds a haunting sequence of narratives around the obsessive love of their brother, Pete, for his dazzling cousin, Tramadol, and its tragic aftermath. Set on the Caribbean island of Jacaranda at different points in a disturbing future, Ghosts weaves a counterpoint between the family wound and a world caught between amazing technological progress and the wounds global warming inflicts on an agitated planet. In a lyrical flow between English and Jamaican Creole, Ghosts catches the ear and gently invades the heart. Love enriches and heals, but its thwarting is revealed as the most painful of emotions. Yet if deep sadness is at the core of the novel, there are also moments of exuberant humour. Curdella Forbes is the critically-acclaimed Jamaican author of Songs of Silence (2002); a collection for younger readers, Flying with Icarus and Other Stories (2003); and more recently A Permanent Freedom (Peepal Tree, 2008). She is currently Professor of Caribbean Literature at Howard University, and lives in Takoma Park, Maryland.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 290

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CURDELLA FORBES

GHOSTS

A MEMOIR

In memory of my brother, Anthony Jehudi Forbes (Tony), October 18, 1958 – July 31, 2000

CONTENTS

Root

I. The Change of Life

II. Death

III. Birth

Fragment

IV. Song

V. Seed

Coda (Afterword)

Acknowledgements

ROOT

My family was born with a wound. Whether it was a private wound, peculiar to us and our generations, or the wound of history, or Adam’s wound, the wound of the world, I do not know. My father’s family was Morris, and my mother’s Pointy. We were born on the Caribbean island of Jacaranda, and though we travelled a great deal and were restless, often even living in other parts of the world, this was where we grew up and this was where, in a manner of speaking, we lived for all of our lives. Our country was colonized by the English for centuries, and so we had these two names, Morris, Pointy, that made it sound as though we were white people, from England, or Scotland, or Ireland, or Wales, though we were black people. In the beginning, when we became curious about our names, we were told that Morris came from the Irish side, because our great great grandfather on my father’s side was Irish. At the time, because we were children, and brought up in an anachronistic, back-o-time household where we knew nothing about sexual intercourse except that sometimes young couples were found giggling in corners, and sometimes adults sent us away, out of hearing or out of the room, so that they could whisper, it did not occur to us to wonder how my great great grandfather came to be an Irishman, or whether someone, a woman, a girl, had been taken advantage of, which was how in those days in such remote districts as ours, our people spoke about the act of rape.

Pointy, we were told, though I don’t know by whom, came from the French side, a corruption of Ponteau, a name meaning ‘bridge’, after a French Huguenot who escaped to the island in the seventeenth century and impregnated a wandering slave woman who became our ancestor.

A French and an Irish side, divided by a channel of water, for which a bridge was needed for crossing over.

The only person I ever heard speak about the African side, the side that showed in our skins and our faces, was our mother. She did not speak of this side as though it was a part of our name. Not because she was ashamed, but because she took it for granted that we were black, and to show this, no name was necessary. To be a person, my mother said, was just to be. You asked questions about who you were, only when you were unsure. But we lived above the banks of a river in a behind-God-back district in a far far country, and every morning when the mists rose above the water, my mother saw processions of slave women with washpans on their heads, passing along the riverbank on their way to somewhere that caused them to sing – whether in repudiation or celebration, my mother could not tell, because the murmur of their voices was one with the sound of the river water washing over the stones. She told us about these daily sightings, and I thought these women whom she saw might be our long ago relatives, since other generations of us had lived there before. But so had the generations of the rest of the district, so who was to say? Our family was so huge and sprawling, and as children growing up we were so happy, our lives so full (of adventure, of quarrelling, of dreaming, of laughing, of chaos), that we never worried about these things; limbs missing from family trees were neither things we cared about, nor wounds that we even knew we had.

My aunt had a vague memory that we had some Indian blood, which has left no mark except in the wideness of the kinks in our hair, which could as well have been on account of the Irish. Our Indian forbear, she said, was a coolie-royal boy (a boy of mixed Indian and African blood, which in our country was royalty, not disgrace, not dougla) who turned up at the gate of our great grandmother on the Morris side when she was barely sixteen, and she loved him so fiercely and so well because of the glow in the wide black curls of his hair, that she walked out of her father’s gate with her clothes tied up in one bundle, took his hand in hers and left her district forever, to settle with him, her perfect prince, in the district that became our home. But her father never spoke to her again, and wrote in his will that she was to get only a Willix penny, ‘on account of inappropriate behaviour’. People in the district and everywhere I have travelled, say that the slant in my eyes is Chinese, but we have no knowledge of this, and moreover we have seen Africans with slanted eyes.

It is easy to make much of these things, but they are not the real story of our wound. I mention them only to give a little background about us. Our wound was not a wound we knew about from the beginning. We knew it was there only because of the strange deformities it produced in us: double limbs, replicated organs, superstitions, dreams, uncanny affections, genius, peculiar retardations, quarrels, guilt, an abiding desire to rescue and be rescued, and the most implacable tendency to obsession. The brief, half-told story that follows in these pages is the story of how these wounds manifested in one small node, in one capsule of time, in the lives of the elder four of us, over a period of years. You could say it is the story of how my brother died, and when, and where, and why, and the story of the various ways in which, because of this, all of us died, and lived.

Because we lived in a district that was small and isolated, yet constantly open to global traffic in any number of ways (journeys – to and fro –, internets, remittances, telephones, cables, books, an obsession with looking out over mountains to where there was another sea) a great many rumours circulated about me and my siblings, and it was said that our family was mad. Truth to tell, I believe my family is mad. But this rumour was not the story that I wanted our grandchildren and grandnieces and grandnephews to hear, when their time came to ask the questions they would inevitably ask about the family and its scars. So I said to my siblings, let us make an album, a family album telling our part in what happened to our brother, and I will put it together for our children.

I gave my word that I would play no part except the part of putting it together, because I knew I did not have their trust. My sister Beatrice spoke for the others when she said my lying tongue would get in the way of everybody’s truth. I have made my living as a writer, and so my siblings have never trusted me. When I close a book and later reopen it, I find that the words have slipped out of joint, out of their assigned places, as if print is written in water. And I find myself mending the story, trying to fix it in its place. A futile and heartsick undertaking, not to mention a perverse one, since a story already deformed is incapable of staying in its place, and will fight very hard to lead you by the nose, and it will win, always it will win, once I try to tamper, because the taint in the story that made it slip out of joint in the first place was not in the story but in me. If you gave me a thousand and one days, it would still be marred forever.

So I tried very hard to keep out of this one, which is a memoir, in which the facts must have their day, a family memoir, in which each of us must have room to speak. Still, only three of my siblings were willing to take the risk of handing over their stories to me, even for posterity’s sake. This, and the family wound, which still longs to shield itself, is the reason this album is a fragment, a brief stitching of fragments torn from a claw, the claw of memory, of forgetting.

I humbly thank my sister Beatrice and my sister Evangeline for their trust in me. Their stories are here faithfully set down, as they gave them to me. I thank also my mother Seraphine for the family histories she told us on the front step, shelling peas, or in the kitchen, stirring pone. These histories helped me to stitch together the parts that happened before I was born.

I pay homage to my brother Pete, from whose diaries the story of his relationship with our cousin Tramadol is pieced together. For the most part I have set down his exact narrative as set out in the diaries. It is only at the end, where I have imagined Tram’s long struggle with the change of life, based on her telephone conversations with Beatrice, that I have allowed my own words to intervene. The decision to use Pete’s diaries, when he was not there to give us permission, was a very hard one indeed, but I think it was the right decision because it reveals the beauty of my brother and the integrity of my cousin, which are contrary to the rumours circulating. I think Pete wanted me to do this, because of the way he left the diaries, in the secret compartment of the strong box to which, in his will, he left me the key.

I thank especially my elder sister Evangeline, who did not write her story herself but gave me permission to write it for her. It is characteristic of the grace of this sister, whom we call the seer, that she did not ask to see the script before I placed it in the album. It is also characteristic that in this album she takes up more space than everyone else, even when she is self-effacing, as she always, truly, is. The humblest ones loom largest in our eyes. I tell myself this is the reason there is more from my keyboard than from the others’, this and not the fact that I may have gone overboard, chasing after the words that again unlodged themselves, when it was my turn to speak. If there is too much of me in this album, forgive.

My final word to our generations is this: I do not know how you will interpret this album. I have not tried to link it to any history except the immediate history of our private, familial, psychic wounds, but it may be that you will find other linkages, other cleavages, in the history we share with others in our country and the rest of the world. It is not for me to say. There is one thing though, a set of facts, that I discovered about our family after this album was put together, that might actually help you to make sense of it all. This I placed in the Afterword (which I have entitled ‘Coda’) so as not to detract from your freedom in drawing your own conclusions.

And finally. (In my country, we conclude twice, and say goodnight many times, going out the door). In the Global Museum of Printed Books, of which a branch is located in the Institute of Jacaranda at this time, there is a book of tales in which is to be found one entitled ‘The Six Swans’. There were six brothers and one sister, and because of a wickedness (not theirs) over which they had no control, the brothers were changed into swans, and sent away, and could only be made human and to return again, if their sister sewed for them magic shirts, over seven years, without speaking. And this she did succeed in doing, except that before the sixth shirt could be finished, she spoke prematurely, out of necessity, and the youngest brother got a shirt without a sleeve, and thus received back intact only one arm, remaining forever winged. I imagine that with one arm and one wing, this maiming and freedom on both sides, this boy, like his sister who invented without speaking, and then spoke and could no longer invent (she, like him, maimed and free in both instances), would always be struggling to put things back in their places, a place of perfection, to put back together flying and grounding, speech and silence, both and each together in a balance of timing as exquisite as the timing of the spheres. And yet it may be that if they are doomed to this struggle forever, never reaching fulfilment, it is because the taint is not in either of these two sets of things but in the heart inside of them, which they were given from their father, and their mother, cleaved in the middle, with ventricles carrying blood, one thicker than the other.

And it’s the same thing all over, you know. Not just in our family. So don’t break your heart with bad feeling. By the time you are reading this, the world will have changed beyond recognition. In my own short lifetime so much has happened. We now have computers cleaning our houses and taking our children to school, piloting driverless cars. In another twenty-four months, China and the USA are thinking, construction will begin on their joint-colony on the moon. We have killed out AIDS (though not the common cold; a cure for that eludes us, just to curb our hubris). Now blind people can see as well as seeing-eyed people, and even in Jacaranda, thanks to the Global Electrical Grid, there are some children who don’t know what an electricity pole looks like since the cities have gone wireless. By the time you are reading this, China might have sunk into the sea and Trinidad become the new superpower. Any number can call, don’t fret. But the thing that strikes you is how we still dreaming, still hungering, still hoping, still having faith, still getting fat or maaga or slim; and how we still destroying, with every move of progress we make: look how many diseases replacing AIDS; how many people hungry all the time; how much war fight; and as I put this album together I can’t help wondering if any of you, my children’s children, my nieces’ children, my nephews’ children, will be here to read it, seeing-eye or no seeing eye, if the sea don’t stop caving in on us from greenhouse gas or that big hole in the ozone don’t stop turning our skin blue. For no matter what change, the heart don’t change. And is out of heart all these things come, one ventricle thicker than the other.

But your grand- aunt, or your ancestor, Evangeline, says we live by God’s grace.

May you by grace be holding in your hands this flutter of pieces, this frazzle of flight, after we done put it away.

I

THE CHANGE OF LIFE

On October 24, 2014, Tramadol Pointy suddenly became beautiful. That is to say, after years (two to be exact) of watching, heartbroken, the easy-walking lilt of girls with wire waists, dutchpot derrières and upstanding, ripe-naseberry breasts, girls bright-eyed and flush with the knowingness of their beauty and irresistibly tinkling feet, Tramadol looked into the suddenly shining mirror on her wall and saw in her own eyes and lips grown violet and lush with promise, her pert breasts and come-out-of-nowhere hips rounding like plump pears above now impossibly long legs, something that she knew would change the shape the world had taken up to that present time. Beyond the discomfiture of thirsty schoolboys clamouring at the fountain of her love, Tramadol looked into the future and saw a place of fire and ice where her feet were now set, towards a destiny that had been marked out for her, without her collaboration or will. It was as devastating as if she had looked into the mirror and found she had become a beetle.

This sudden revelation came at a price. Tramadol was my cousin. And she inherited the family curse like the rest of us. Straight after her transformation she developed three obsessions: a deep hunger for love, that is to say, the expectation of a prince, fiercer than fire or time, who would show her the meaning and origin of the stars; a desire for faraway places, places struck deep, like newly minted coin, with desert fire or the ice of fjords, mountains of frost breaking apart the face of oceans; and, at the last, an obsession with antique timepieces, among which she numbered an hourglass full of mercury. If she had been forced to give an account of these passions, Tramadol would have denied that they had anything to do with the hold reading had on her. That is to say, even though to escape the taunts of schoolmates who mocked her for lacking breasts and hips and the bursting facial pustules that announced the onset of womanhood; scorned her for wearing shoes that her grandfather had patched with his own hands using thread that showed grey against the dark brown of the shoes; giggled when she missed so many days at school that the English mistress scarcely raised her head to remark, ‘I see you are with us today, Inspector’; mimicked her for being unable to speak, her tongue tied with the perpetual anguish of her outsiderness – even though to escape the pain of all this, Tramadol had for many years buried herself in the cool forests of certain kinds of books, with angry deserts, ice mountains, and romances that flared between princes and princesses on cobalt seas*, she would have said her passions had nothing to do with bookish romance, but something else altogether. That something else I leave to you to discern. But be patient for the story of this love. It unfolds slowly, it going tek time.

With the coming of her beauty Tramadol raided heart closets and killed dragons. Boys at school fell like ninepins. It wasn’t Tramadol’s desire to slay any: her sole aim and driving thirst was to find the one man worthy of loving her, her prince of away places, her man of fire and uncareful feet, and ice. Tram was one of those girls who treated men badly because she was beautiful and she knew that made us stupid. At the same time, she behaved towards her beauty like a deprived child let loose in a toy shop; like any young girl in her position, she flirted lavishly, and with a fine and prodigal cruelty. Yet she was exceedingly vulnerable to the idea of love, and on three distinct occasions my cousin fell briefly, violently, and with a storm of tears, in love.

As each of the three would-be princes failed the test, my cousin blamed herself for setting her sights too low. The thing that you have to understood about my cousin – the thing that few people knew, for very few, if any, knew her at all (even I who was closest to her, knew her less through intimacy than through the cage of a haunted imagination) – is that she gave her total allegiance to love; for her, love was the highest value, and to offer or ask less than the best from love was the worst form of apostasy. If she had been religious you could have called her a visionary. As it was, I used to think she had been born in the wrong place and time. I imagined her against a backdrop of olive groves, in ancient Greece, a votary at Aphrodite’s shrine, or a virgin in calm desert tents, feeding pomegranate seeds to princes. The names that people used to call her as a heartless heartbreaker – Sketel, Boy Crazy, Man Crazy, Tek Too Much Man, Iron Front, Gi Man Bun, Tram-Car (Everybody ride pon har) – she didn’t deserve, first because my cousin was very chaste, and second, because with every failure you saw in her eyes a desolation that said her grief was even greater than her suitor’s. But beauty such as Tramadol’s is the stuff of which legends are made, and these nicknames, denoting a gargantuan sexual appetite, served the cause of legend as well as the need of expiation (for extreme beauty has always to be atoned for).

Each time she called off an assay into a new relationship (for you couldn’t call these knot-up ropes actual relationships), my cousin retreated to her room and lay on her bed for many days, not moving, staring up at the invisible ceiling above the concrete one, like a self-abnegating prophetess waiting for a sign. Nothing I did could bring her out of these trances. That is to say, sometimes, if I beat the door long and hard enough, she opened it, let me in, and went back to her speechless vigil, ignoring both my words and my silence, offered in what (vainly, with self-acknowledged hubris) I hoped was close companionship; at other times, after she let me in, she answered my questions in riddles, mystical sayings and bookish quotations that were as strong a wall as when she didn’t say anything. My cousin had lived inside her own head for so long that she made up a language of her own, the kind that twins make up when they want to keep everyone else out.

Most of the time she wouldn’t open the door.

During these crises my cousin again underwent strange transformations. Her face and body would pass through a series of grotesques, huge serpentine twistings that I, the only witness, never dreamed of divulging to the family. First, who would believe me? And second, they invoked in me a deep superstition, the fear that if I spoke them, the words would become flesh and either my cousin would be doomed to encounter them forever, or I too would be taken over and become forever the bodily cage of writhing lamias, higues and ancient soucouyants. I cried out in my sleep with the burden and secret of them. Sometimes, even now, as if it’s happening again, I relive the terror I felt whenever in the midst of one of these seizures my mother stopped at the door to demand, ‘What’s going on in there? What the two of you lock up inside there doing?’ They made my cousin exceedingly ugly, with the ugliness that one finds at the roots of cotton trees guarding skulls that rain has washed out from the soil, long after the graves have sunk – graves made in the old days before people were buried in concrete vaults and were instead put direct into the ground in cedar boxes. Tramadol’s face had the same stark ugliness of beauty stretched to its uttermost extreme, the ghastly, naked skull of confrontation and the black roots of nether substance that sheltered it. After each terrific convulsion, her face smoothed out like a sheet of brown paper, beautiful and pure once more, the tortured limbs slowly following suit, curving sweet like the lilt of songs. I could not begin to guess what horrors, or ecstasies my cousin encountered in the grip of these dread trances.

‘But what yu really want, Tram?’ I asked on one of the rare occasions when she opened the door. ‘Yu confuse me same as how yu confuse the yout-dem dat checking yu. Yu vex wid dis one because him don’t open the door for yu, ladies before gentlemen, him catch up himself, yu run him. Yu say t’idda one too mean, yu hate man dat come to visit yu wid nutten in him hand an first ting him do is open yu fridge. Well, mi understand dat. But yu talk to him bout it, him repent, him half kill yu wid flowers an poetry an apology, the yout tun yu slave, yu seh him too conceited. If me was a woman an yout change like dat fi mi, mi heng on pon him. An what about Charlie? Granted mi nuh like di bredda, but Charlie is the gentleman’s gentleman, mi see di bredda walk pon water fi yu. So what’s the score?’

‘Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels,’ Tram said obscurely.

‘What?’

‘First Corinthians 13. Hymn to love. It tell yu what is real love.’

‘Tram, don’t gimmi dat for yu don’t even believe inna Bible. Yu hate church like how puss hate water. Yu not Evangeline. So where dis coming from?’

‘Yes, but dem don’t offer love,’ my cousin said, by way of translation. ‘Those are just trivialities. Is what they point to you must look at.’

‘But Tram, not opening the door can be just upbringing, you know. First of all how many guys you know who know anything bout dem kinda ting from dem yard? And furthermore, these days it so confusing – the way some o oonu woman go on, it mek man think opening door an dem kinda ting dere is anti-feminist, like thinking of the woman as the weaker vessel. Yu remember when Aunt Rita sprain her back and had to travel from Birmingham to London to catch the plane from Heathrow to come home, and she couldn’t lift her suitcase in the train and the whole heap a man pass her there, none o dem offer to help?’

Tram sucked her teeth. ‘Cheups. Dat nuh feminism, dat a racism. So nuh bring no white man into dis conversation. Tell mi something: dese boys dat brukking dem neck to get into mi underclothes, dem don’t go to school? Dem might born a backabush, but dem go to school, dem suppose to learn something. An if dem nuh learn it, dem damn dunce so mi wussar don’t want dem. Is not just the opening of the door – yu never notice how di boy always expec mi fi walk backa him? Him always a lead di way, always out in front. Is a personality defect dat.’ After a silence she added in the prim voice that told you she didn’t want to cry, ‘It points to a certain lack of emotional intelligence.’

It was a long speech for her, exceedingly rare.

‘Can a man change?’

I asked this hopelessly, because even then I knew she didn’t think of me as a man. The price I paid was her confidence. Even then, I knew I would love her forever. Even if even second cousins could not marry, could not boil good soup, except in the sly proverb that said cousins sometimes did, in secret. Cousin an cousin boil good soup. Hee hee. It was the main reason my mother would tear off the door, metaphorically speaking, to get us to open up so she could see or smell what we had been doing. My mother had no idea that I was the safest person in the whole wide world to Tram, because Tram thought of me as a sister. Six feet by the time I was fourteen and my cousin thought I was a girl.

‘Hog mout nuh grow long overnight.’

I understood the cryptogram. This was my cousin’s way of saying, sure, a man can change, in so far as he grows into the person he is going to become, but nobody changes at the fundament. Pretty much, the apparatus you start out with is what you carry to your grave.

‘But suppose what yu seeing now is di –’ I struggled for a word, ‘you know, di – call it then di excess – di excess dat show dat the man don’t grow into him full self as yet? Like cane trash – yu know, how cane trash can cover good cane an yu haffi tear it off to see the real juicy cane underneath?’

‘Boss man, if yu see a snake a-run pon top o di cane, chances are, one nest underneath there.’

‘So yu nuh see no potential dat yu can work with, in any man so far?’

‘Boy pickini, hear dis. I don’t want no man potential. Dat is like eating air pie an breeze pudding. Yu see me offering any man my potential? Fixing up myself is my responsibility. Dem, ditto.’

I never knew anyone as exigent as Tram. Most girls – and later, women – I knew were willing to forgive a man many things. Probably most things. Even my sisters, who were strong, independent women, had forged forms of compromise they could live with. Beatrice, the fiercest of them, said the one thing she could never forgive was physical abuse. ‘Dat kind of man never change,’ according to B. ‘It in dem DNA. Psychiatrist might mask it for a while, but sooner or later it front up again, just like how the sea going come back one day an reclaim all dem dump-up land where they put house and call it city. Water find its own level. Man like that, nuh fi go near no woman, mus stay by himself.’

I agreed with B; we had grown up in a district where two well known women, married to two brothers, were constantly at the receiving end of domestic assault and battery; my mother, the district’s unofficial lawyer, on occasion took it upon herself to gather posses of villagers to go and drag these men off their wives, on whom they’d be sitting wielding cricket bats and once even a knife. And when we were young together, before I got introduced to the pleasures of sexual intercourse and found that it had nothing to do with commitment, I agreed with B and Peaches that infidelity was also serious cause for concern and in certain cases would have to be fatal. I know I could not have been unfaithful to Tram, even if I had wanted to. My cousin made no exceptions, gave no quarter.

Tramadol’s pronouncements on the subject of men are responsible for my bachelorhood. Either I seem to have spent my life looking for her in other women’s faces, or she instilled in me such an absolute terror of falling short, that I make tracks as soon as a woman I’m involved with starts asking the kind of questions that mean she wants to ‘get to know me better’ – code for checking me out as potential husband material.

Tram was probably the brightest of us, but she didn’t do well in school. For one thing, the crises of broken love drained her strength. But she was also convinced that you shouldn’t waste time on irrelevancies, including those your parents prescribed for your own good. And so once she knew what her own destiny was, she pursued it with fierce and single-minded concentration so that her schoolwork suffered, and her tendency to retreat into the world made by words, that is to say, the words of others that made new worlds out of thin air (for she herself hardly spoke) became morbid. At intervals she could not bear to be inside a building, otherwise she became feverish, once catching pneumonia. Her only relief at such times was to take walks, over and over again, by the river that ran below my grandparents’ house. Indian kale used to grow there, and she would look deeply into their roots, like someone reading runes. She read as well birds, flowers, canes, the shape of rose-apples – the little golden fruit smelling of perfume that also grew by the water – and the strange figures that whirled in the pools. She was fascinated by the upside down world under the surface of river water. For my cousin, all of these things posed parables, hieroglyphs of meaning that were the key to what the universe meant, a parallel world which was the real image of the one we saw when we opened our eyes in the morning. In all of this, Tramadol was looking for ways to recognize her prince, so when he came she would know him. (Be patient for the story of this love. It unfolds slowly, like roses in cool places).

Over the years, at various stages of hindsight, I have tried to work out why my cousin chained me so completely to herself, even though I was obviously not the prince. I think that because I was myself so ordinary, I fell profoundly in love with my cousin’s way of saving herself. Tram knew that life poses itself as a riddle – that it offered more than anyone could see with the naked eye, but most people didn’t know that, or if they knew, the terror of the price to be paid made them willing to settle for a little (or a great deal) less. Tram was the only person I knew who refused to compromise on the promise of life. She was going to seize it by the throat and make it give up everything it had hidden in its marrow, perversely stashed away for the violent. Here again my cousin quoted the Bible, in which she had no religious interest.

‘Only the violent take it by force, boss boy,’ she said in one of her rare moments, eyes glistening with a desire for the fray that I found sexually exciting. ‘To go in and out without hindrance at all the gates of the Duat.’ That was from the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

I didn’t think of what I came to call Tram’s way as possibly a form of perversity, maybe because I was too obsessed with her, with the obsession of the ordinary for the spectacular. That is to say, I didn’t wonder whether what I saw in her as integrity was in fact a deep selfishness, or whether her absolute certainty about what she wanted was more accurately a profound cynicism, frightening in one so young. It was Tramadol who, constantly self tortured, asked those questions of herself, over and over again in Gordian knots like a lamia’s tail, or a rolling calf’s chain. My cousin was both tortured and free. I thought her brave and splendid, like the full round moon. Yet I constantly struggled with her, out of a conviction that at the centre of the world there was a bridge, called Compromise, which everyone crossed over to get to the other side, but no one could go on unless someone on the opposite bank came to meet them halfway, and then the two returned together.

In contrast, what Tram saw at the centre of the world was the lake of fire and ice, which was to be won only by many passages of death, and which, once one dipped one’s body in it, would open one’s eyes to reveal the one twin soul, who had also come all the way, not halfway, on this journey, and with whom one would return across the freezing, burning steppes, one’s body also transformed.