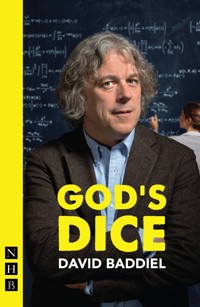

13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Science and religion go head to head in David Baddiel's debut play: a ferociously funny battle for power, fame and followers. When physics student Edie seems to prove, scientifically, the existence of God, it has far-reaching effects. Not least for her lecturer, Henry Brook, his marriage to celebrity atheist author Virginia – and his entire universe. God's Dice is an electric tragicomedy about the power of belief and our quest for truth in a fractured world. It premiered at Soho Theatre, London, in October 2019, starring Alan Davies as Henry, and directed by James Grieve.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

GOD’S DICE

David Baddiel

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Original Production

Introduction

Characters

God’s Dice

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

God’s Dice was first performed on 24 October 2019 at Soho Theatre, London, presented by Soho Theatre and Avalon. The cast was as follows:

HENRY

Alan Davies

EDIE

Leila Mimmack

VIRGINIA

Alexandra Gilbreath

TIM

Nitin Ganatra

INTERLOCUTER and BILLY

Adam Strawford

Director

James Grieve

Set and Costume Designer

Lucy Osborne

Lighting Designer

Ric Mountjoy

Sound Designer

Dominic Kennedy

Video Designer

Ash J Woodward

Casting Director

Nadine Rennie CDG

Costume Supervisor

Jackie Orton

Assistant Director

Sophie Drake

Production Manager

Seb Cannings for Gary

Production Manager

Seb Cannings for Gary

Beestone Events & Theatre

Company Stage Manager

Anna Hunscott

Assistant Stage Manager

Amber Reece-Greenhalgh

Wardrobe Assistant

Clementine Curry

Produced by

Soho Theatre and Avalon

Producer

Emma Brünjes for Avalon

Producer

Alex Turner for Soho Theatre

Assistant Producer

Holly De Angelis

Marketing

JHI Marketing

Press and PR

Jo Allan PR

Introduction

My dad was a scientist – still is, even through the fog of dementia (if you ask him what the chemical formula for salt is, he’ll still shout NACKL!, a my-dad word for NaCl, or sodium chloride). I’m not. I was going to be – I had chosen Chemistry, Physics and Maths A levels – but that was because, in our family, because of my dad, science was King: no other form of intellectual endeavor was considered of any value. Luckily for me, and the scientific world, I realised at the last minute that regularly getting Ds and Es in science subjects, whilst doing considerably better in arts and humanities, meant that I should focus on those. When I, with some trepidation, told my dad, he said: ‘It’s a waste of a brain.’ Hmm. But then anyone who saw my last theatrical outing, my one-man show My Family: Not the Sitcom will know that what we would now call ‘parenting’ was not his strong point.

Anyway: unlike Luke Skywalker, I am not my father’s son. I think watching, or indeed writing, books and plays and films is not a waste of a brain. But something must have stuck, or some return of the repressed is happening. Because as I get older I’ve found myself reading, amongst all the novels and plays, a lot of science books. Not proper ones, obviously, the sort that students have to plough through at university, but the popular kind – by Brian Cox and Carlo Rovelli and Brian Greene. Ones that do their best, for those of us who can hardly add up the price of their weekly shop, to explain the mysteries of modern physics without mathematics.

The correct equation is probably my father plus mortality. As you get older, you see your time left to understand what the universe is truly about narrowing, and a part of me – my father – suspects that the only real understanding lies in science. Specifically, quantum physics: because there is something about looking deep into the microscopic heart of things that surely – almost banally – will give you that answer. We are visual animals, and we think if we peer deep enough, we will always crack mystery.

Wrong, of course. I noticed that, however much I read, I never quite understood. Sometimes I would get close only for the sliver of understanding to vanish with a turn of the page and a new analogy involving clocks or ripples in a pond. Richard Feynman, one of those who looked very deeply into this mystery, said ‘I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.’ Even a smattering of knowledge of quantum physics will very quickly lead you to the conclusion that, the more you look, the less you understand. At the microscopic heart of things, mystery is not cracked: there is just more mystery. In fact, there is more than mystery, there is stuff that feels completely strange and weird and… well, miraculous. Which means that when scientists tell us: ‘Sorry, that IS the way things are – we can’t really explain it, you’re just going to have to accept it – you’re simply going to have to believe us’ – it rang, for me, a familiar bell: a church one.

Or a mosque/synagogue/Zoroastrian Fire Temple one (yes I know they probably don’t have bells…). In the realm of quantum physics, scientists seem to me to be like medieval priests. They have the obscure difficult language that only they understand – maths – and they are tasked with conveying the fundamental truths of the universe this language reveals to them back to the rest of us, using analogies and stories and reassurance. We have to have faith in this science, that tells us that everything we think we apprehend is something else entirely; that all we see is as through a glass, darkly, even if that glass is the lens of an electron microscope. Or at least that’s how it felt to me, reading these books. Without a deep understanding of mathematics, there comes a point where you have to trust the wise ones. There comes a point, in other words, where you have to make a leap of faith.

The realisation that these two great shards of thought cross over in a Venn diagram involving faith, mystery, the miraculous, and a questioning of apparent reality brought me to thinking about the world we live in now, how much we seem to be in a time of desperate believing, but with less and less sense that what is believed is necessarily true. Truth has got very mixed up, it seems, with desire… so, anyway, I decided to try and write a play about all this, in which all those big concerns bang up against some more mundane faiths, the ones that sustain us from day to day: in love and marriage and friendship and the value of teaching and knowing one’s place in the world. I hope you enjoy it. And that you close these pages thinking that I haven’t, in the end, completely wasted my brain.

David Baddiel

October 2019

Characters

HENRY, fifties

EDIE, twenties

VIRGINIA, forties

TIM, fifties

BILLY, twenties

This ebook was created before the end of rehearsals and so may differ slightly from the play as performed.

ACT ONE

Darkness: Music. The guitar chords of a slow acoustic version of ‘Do Anything You Wanna Do’ by Eddie & The Hot Rods.Bring up slowly the sounds of students arriving at a lecture hall.

Lights up. A lecture hall at a redbrick university. It is Exeter, but it could be any.

Behind a lectern, surveying his students (who figure here as the audience) is a lecturer, with a friendly demeanour: HENRY BROOK, fifty. Next to him on the lectern is a glass of water.

There are a number of laptops dotted around the stage, with the screens up, facing the audience. At present they all show a screensaver of Exeter University.

Behind HENRY is a whiteboard, divided into two sections bya line down the middle. This needs to be a usuable whiteboard –i.e. writeable on – and available for projecting.

Above the left-hand section, the words: ‘The sorts of equations that appear on whiteboards in biopics about scientists’.

On the right-hand section: ‘UNDERSTANDING PHYSICS’. HENRY underlines it.

He turns. Half-smiles.

HENRY. So. Who here would like to win the lottery?

Beat.

No one? I’m going to assume that’s just shyness in a group of new students. I’m going to assume we all would like that. How do we make that happen? How do we without any shadow of doubt, win the lottery? There is one absolute way.

Beat.

Kill yourself.

Beat, enjoying the effect.

I should be clear – I don’t advise actually doing this. It’s fraught with problems. You might get it wrong and end up horrifically injured. Plus, more importantly, you have to have a lot of faith – for want of a better word – in the idea of the many-worlds universe. But let’s assume we do have that faith. Let’s assume – just for a laugh – that the universe is indeed infinite, and anything that can happen, will happen. If you do, winning the lottery is very simple.

He goes over to the whiteboard. Talks, as he rubs off what’s on there.

Firstly, you have to buy a lottery ticket. Let’s say the numbers on your ticket are – let’s make this easy – one two three four five – and a bonus ball: six.

Writes those numbers on the board.

Then what you have to do is go to bed before The National Lottery In It To Win It – or whatever it’s called now – is on. On top of your bed – bit tricky, this bit – you have to construct some kind of device plugged into your TV, that if these numbers do not come up, including the bonus ball, will kill you.

He draws a version of what he’s talking of.

Perhaps a ten-tonne anvil held in a magnetic field above your bed that responds to Alan Dedicoat’s voice. Who knows? It’s not important. What is important is that – even though you’ll almost definitely be killed in this world, and most of the others in the multiverse – in one of the many worlds – these numbers will come up. In an infinite universe, they must do, somewhere. In fact, since the chances of winning the lottery on any normal week are in fact one in thirteen million, nine hundred and eighty-three thousand, eight hundred and sixteen, you won’t even be killed in that many worlds. You’ll be killed, to be exact, in thirteen million, nine hundred and eighty-three thousand, eight hundred and fifteen worlds. But in the thirteen million, nine hundred and eighty-three thousand and eight hundred and sixteenth, you’ll wake up – alive and rich beyond your wildest dreams. How about that?

Sound of class shutting books, coughing, etc. HENRY checks his watch.

So, look, not everything in my lectures is going to be that exciting. But I thought I’d start you off with something that made you think physics isn’t going to be dull. And therefore that you’d made the right choice for a degree. Google Everett, many-universe theory and the Dirac delta function, and we’ll talk again tomorrow.

Sound of chairs moving back, many students getting up, leaving, a door opening, etc. HENRY starts wiping the whiteboard.

One student, EDIE, appears from the wings. She watches his back for a beat.

EDIE. Professor Brook?

HENRY. Yes?

EDIE. Can I ask you a question?