Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

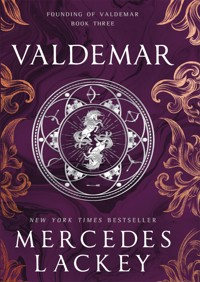

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Gryphon Trilogy

- Sprache: Englisch

The ongoing saga of Valdemar enters a new era with this epic trilogy, from the New York Times bestselling author and Grand Master of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. On the border between Valdemar and the deadly Pelagirs Forest, the gryphon hero Kelvren returns from a near-fatal self-sacrifice that won him the approval of Valdemar's ground troops but caused a diplomatic crisis. Frustrated by his lack of a hero's welcome, Kelvren is talked into helping with an expedition by his old friend, Firesong. Firesong struggles with his own age and mortality, and he intends to solve a vast mystery at the center of legendary Lake Evendim as his crowning achievement. Just getting the multicultural fleet underway is a challenge, but what awaits them is a situation none of them could expect.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 628

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf: