11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Karse and Valdemar have long been enemy kingdoms, until they are forced into an uneasy alliance to defend their lands from the armies of Eastern Empire, which is ruled by a monarch whose magical tactics may be beyond any sorcery known to the Western kingdoms. Forced to combat this dire foe, the Companions of Valdemar may, at last, have to reveal secrets which they have kept hidden for centuries... even from their beloved Heralds.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Mercedes Lackey

Title Page

Copyright

Storm Warning

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Storm Rising

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Storm Breaking

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Also by Mercedes Lackey and available from Titan Books

THE COLLEGIUM CHRONICLES

Foundation

Intrigues

Changes

Redoubt

Bastion

THE HERALD SPY

Closer to Home

Closer to the Heart (October 2015)

Closer to the Chest (October 2016)

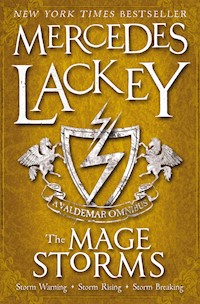

VALDEMAR OMNIBUSES

The Heralds of Valdemar

The Mage Winds

THE ELEMENTAL MASTERS

The Serpent’s Shadow

The Gates of Sleep

Phoenix and Ashes

The Wizard of London

Reserved for the Cat

Unnatural Issue

Home from the Sea

Steadfast

Blood Red

From a High Tower

The Mage Storms OmnibusPrint edition ISBN: 9781783293810E-book edition ISBN: 9781783293827

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: September 20152 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Mercedes Lackey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work. Copyright © 1994, 1995, 1996, 2015 by Mercedes R. Lackey. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Dedicated to Elsie Wollheim with love and respect

1

Emperor Charliss sat upon the Iron Throne, bowed down neither by the visible weight of his years nor the invisible weight of his power. He bore neither the heavy Wolf Crown on his head, nor the equally burdensome robes of state across his shoulders, though both lay nearby, on an ornately trimmed marble bench beside the Iron Throne. The thick silk-velvet robes flowed down the bench and coiled on the floor beside it, a lush weight of pure crimson so heavy it took two strapping young men to lift them into place on the Emperor’s shoulders. The Wolf Crown lay atop the robes, preventing them from slipping off the bench altogether. Let mere kings flaunt their golden crowns; the Emperor boasted a circlet of electrum, inset with thirteen yellow diamonds. Only when one drew near enough to the Emperor to see his eyes clearly did one see that the circlet was not as it seemed, that what had passed at a distance for an abstract design or a floral pattern was, in fact, a design of twelve wolves, and that the winking yellow diamonds were their eyes. Eleven of those wolves were in profile to the watcher, five facing left, six facing right; the twelfth, obviously the pack leader, gazed directly down onto whosoever the Emperor faced, those unwinking yellow eyes staring at the petitioner even as the Emperor’s own eyes did.

Let lesser beings assume thrones of gold or marble; the Emperor held court from his Iron Throne, made from the personal weapons of all those monarchs the Emperors of the past had conquered and deposed, each glazed and guarded against rust. The throne itself was over six feet tall and four feet in width; a monolithic piece of furniture, it was so heavy that it had not been moved so much as a finger-length in centuries. Anyone looking at it could only be struck by its sheer mass—and must begin calculating just how many sword blades, axes, and lance points must have gone into the making of it…

None of this was by chance, of course. Everything about the Emperor’s regalia, his throne, his Audience Chamber, and Crag Castle itself was carefully calculated to reduce a visitor to the proper level of fearful respect, impress upon him the sheer power held in the hands of this ruler, and the utter impossibility of aspiring to such power. The Emperors were not interested in inducing a groveling fear, nor did they intend to excite ambition. The former was a dangerous state; people made too fearful would plot ways to remove the cause of that fear. And ambition was a useful tool in an underling beneath one’s direct supervision, but risky in one who might, on occasion, slip his leash.

There was very little in the Emperor’s life that was not the result of long thought and careful calculation. He had not become the successor to Emperor Lioth at the age of thirty without learning the value of both abilities—and he had not spent the intervening century-and-a-half in letting either ability lapse.

Charliss was the nineteenth Emperor to sit the Iron Throne; none of his predecessors had been less than brilliant, and none had reigned for less than half a century. None had been eliminated by assassins, and only one had been unable to choose his own successor.

Some called Charliss “the Immortal”; that was a fallacy, since he was well aware how few years he had left to him. Although he was a powerful mage, there were limits to the amount of time magic could prolong one’s life. Eventually the body itself became too tired to sustain life any longer; even banked fires dwindled to ash in the end. Charliss’ rumored immortality was one of many myths he himself propagated. Useful rumors were difficult to come by.

The dull gray throne sat in the midst of an expanse of black-veined white marble; the Emperor’s robes, the exact color of fresh-spilled blood, and the yellow gems in the crown, were the only color on the dais. Even the walls and the ceiling of the dais-alcove, a somber setting for a rich gem, were of that same marble. The effect was to concentrate the attention of the onlookers on the Emperor and only the Emperor. The battle-banners, the magnificent tapestries, the rich curtains—all these were behind and to the side of the young man who waited at the Emperor’s feet. Charliss himself wore slate-gray velvets, half-robe with dagged sleeves, trews, and Court-boots, made on the same looms as the crimson robes; in his long-ago youth, his hair had been whitened by the wielding of magic and his once-dark eyes were now the same pale gray as an overcast dawn sky.

If the young man waiting patiently at the foot of the throne was aware of how few years the Emperor had left to him, he had (wisely) never indicated he possessed this dangerous knowledge to anyone. Grand Duke Tremane was about the same age as Charliss had been when Lioth bestowed his power and responsibility on Charliss’ younger, stronger shoulders and had retired to spend the last three years of his life holding off Death with every bit of the concentration he had used holding onto his power.

In no other way were the two of them similar, however. Charliss had been one of Lioth’s many, many sons by way of his state marriages; Tremane was no closer in blood to Charliss than a mere cousin, several times removed. Charliss had been, and still was, an Adept, and in his full powers before he ascended the Throne. Tremane was a mere Master, and never would have the kind of mage-power at his personal command that Charliss had.

But if mage-power or blood-ties were all that was required to take the Throne and the Crown, there were a hundred candidates to be considered before Tremane. Intelligence and cunning were not enough by themselves, either; in a land founded by stranded mercenaries, both were as common as snowflakes in midwinter. No one survived long in Charliss’ court without both those qualities, and the will to use both no matter how stressful personal circumstances were.

Tremane had luck; that was important, but more than the luck itself, Tremane had the ability to recognize when his good fortune had struck, and the capability to revise whatever his current plan was in order to take advantage of that luck. And conversely, when ill-luck struck him (which was seldom), he had the courage to revise plans to meet that as well, now and again snatching a new kind of victory from the brink of disaster.

Tremane was not the only one of the current candidates for the succession to have those qualities, but he was the one personally favored by the Emperor. Tremane was not entirely ruthless; too many of the others were. Being ruthless was not a bad thing, but being entirely ruthless was dangerous. Those who dared to stop at nothing often ended up with enemies who had nothing to lose. Putting an enemy in such a position was an error, for a man who has nothing to lose is, by definition, risking nothing to obtain what he desires.

Tremane inspired tremendous loyalty in his underlings; it had been dreadfully difficult for the Emperor’s Spymaster to insinuate agents into Tremane’s household. That was another useful trait for an Emperor to have; Charliss shared it, and had found that it was just as effective to have underlings willing to fling themselves in front of the assassin’s blade without a single thought as it was to ferret out the assassin himself.

Otherwise, the man on the throne had little else in common with his chosen successor. Charliss had been considered handsome in his day, and the longing glances of the women in his Court even yet were not entirely due to the power and prestige that were granted to an Imperial mistress. Tremane was, to put it bluntly, so far from comely that it was likely only his power, rank, and personal prestige that won women to his bed. His thinning hair was much shorter than was fashionable; his receding hairline gave him a look of perpetual befuddlement. His eyes were too small, set just a hair too far apart; his beard was sparse, and looked like an afterthought. His thin face ended in a lantern jaw; his wiry body gave no hint of his quality as a warrior. Charliss often thought that the man’s tailor ought to be taken out and hanged; he dressed Tremane in sober browns and blacks that did nothing for his complexion, and his clothing hung on him as if he had recently lost weight and muscle.

Then again… Tremane was only one of several candidates for the Iron Throne, and he knew it. He looked harmless; common, and of average intelligence, but no more than that. It was entirely possible that all of this was a deeply laid plan to appear ineffectual. If so, Charliss’ own network of intelligence agents told him that the plan had succeeded, at least among the rest of the rivals for the position. Of all of the candidates for the Iron Throne, he was the one with the fewest enemies among his rivals.

They were as occupied with eliminating each other as in improving their own positions, and in proving their ability to the Emperor. He was free to concentrate on competence. This was not a bad position to be in.

Perhaps he was even more clever than Charliss had given him credit for. If so, he would need every bit of that cleverness in the task Charliss was about to assign him to.

The Emperor had not donned robes and regalia for this interview, as this was not precisely official; he was alone with Tremane—if one discounted the ever-present bodyguards—and the trappings of Empire did not impress the Grand Duke. Real power did, and real power was what Charliss held in abundance. He was power, and with the discerning, he did not need to weary himself with his regalia to prove that.

He cleared his throat, and Tremane bowed slightly in acknowledgment.

“I intend to retire at some point within the next ten years.” Charliss made the statement calmly, but a muscle jumping in Tremane’s shoulders betrayed the man’s excitement and sudden tension. “It is Imperial custom to select a successor at some point during the last ten years of the reign so as to assure an orderly transition.”

Tremane nodded, with just the proper shading of respect. Charliss noted with approval that Tremane did not respond with toadying phrases like “how could you even think of retiring, my Emperor,” or “surely it is too early to be thinking of such things.” Not that Charliss had expected such a response from him; Tremane was far too clever.

“Now,” Charliss continued, leaning back a little into the comfortable solidity of the Iron Throne, “you are no one’s fool, Tremane. You have obviously been aware for a long time that you are one of the primary candidates to be my successor.”

Tremane bowed correctly, his eyes never leaving Charliss’ face. “I was aware of that, certainly, my Emperor,” he replied, his voice smoothly neutral. “Only a fool would have failed to notice your interest. But I am also aware that I am just one of a number of possible candidates.”

Charliss smiled, ever so slightly, with approval. Good. Even if the man did not possess humility, he could feign it convincingly. Another valuable ability.

“You happen to be my current personal choice, Tremane,” the Emperor replied, and he smiled again as the man’s eyebrows twitched with quickly-concealed surprise. “It is true that you are not an Adept; it is true that you are not in the direct Imperial bloodline. It is also true that of the nineteen Emperors, only eleven have been full Adepts, and it is equally true that I have outlived my own offspring. Had any of them inherited my mage-powers, that would not have been the case, of course…”

He allowed himself a moment to brood on the injustice of that. Of all the children of his many marriages of state, not a one had achieved more than Journeyman status. That was simply not enough power to prolong life—not without resorting to blood-magic, at any rate, and while there had been an Emperor or two who had followed the darker paths, those were dangerous paths to follow for long. As witness the idiot Ancar, for instance—those who practiced the blood-paths all too often found that the magic had become the master, and the mage, the slave. The Emperor who ruled with the aid of blood-rites balanced on a spider’s thread above the abyss, with the monsters waiting below for a single missed step.

Well, it hardly mattered. What did matter was that a worthy candidate stood before him now, a man who had all the character and strength the Iron Throne demanded.

And what was more, there was an opportunity before them both for Tremane to prove, beyond the faintest shadow of a doubt, that he was the only man with that kind of character and strength.

“Your duchy is in the farthest west, is it not?” Charliss asked, with carefully simulated casualness. If Tremane was surprised at the apparent change of subject, he did not show it. He simply nodded again.

“The western border, in fact?” Charliss continued. “The border of the Empire and Hardorn?”

“Perhaps a trifle north of the true Hardorn border, but yes, my Emperor,” Tremane agreed. “May I assume this has something to do with the recent conquests that our forces have made in that sad and disorganized land?”

“You may.” Charliss was enjoying this little conversation. “In fact, the situation with Hardorn offers you a unique opportunity to prove yourself to me. With that situation you may prove conclusively that you are worthy of the Wolf Crown.”

Tremane’s eyes widened, and his hands trembled, just for a moment.

“If the Emperor would be kind enough to inform his servant how this could be done—?” Tremane replied delicately.

The Emperor smiled thinly. “First, let me impart to you a few bits of privileged information. Immediately prior to the collapse of the Hardornen palace—and I mean that quite precisely—our envoy returned to us from King Ancar’s court by means of a Gate. He did not have a great deal of information to offer, however, since he arrived with a knife buried in his heart, a rather lovely throwing dagger, which I happen to have here now.”

He removed the knife from a sheath beneath his sleeve, and passed it to Tremane, who examined it closely, and started visibly when he saw the device carved into the pommel-nut.

“This is the royal crest of the Kingdom of Valdemar,” Tremane stated flatly, passing the blade back to the Emperor, who returned it to the sheath. Charliss nodded, pleased that Tremane had actually recognized it.

“Indeed. And one wonders how such a blade could possibly have been where it was.” He allowed one eyebrow to rise. “There is a trifle more; we had an intimate agent working to rid us of Ancar, an agent that had once worked independently in Valdemar. This agent is now rather conspicuously missing.”

The agent in question had been a sorceress by the name of Hulda—Charliss never could recall the rest of her name. He did not particularly mourn her loss; she had been very ambitious, and he had foreseen a time when he might expect her value as an agent to be exceeded by her liabilities. That she was missing could mean any one of several things, but it did not much matter whether she had fled or died; the result would be the same.

Tremane’s brow wrinkled in thought. “The most obvious conclusion would be that your agent turned,” he said after a moment, “and that she used this dagger to place suspicion on agents of one of Ancar’s enemies, thus embroiling us in a conflict with Valdemar that would open opportunities for her own ambitions in Hardorn. We have no reason for an open quarrel with Valdemar just yet; this could precipitate one before we are ready.”

Charliss nodded with satisfaction. What was “obvious” to Tremane was far from obvious to those who looked no deeper than the surface of things. “Of course, I have no intention of pursuing an open quarrel with Valdemar just yet,” he said. “The envoy in question was hardly outstanding; there are a dozen more who are simply panting for his position. The woman was quite troublesomely ambitious, yes; however, if she uses her magics but once, we will know where she is, and eliminate her if we choose. No. What truly concerns me is Valdemar itself. The situation within Hardorn is unstable. We have acquired half of the country with very little effort, but the ungrateful barbarians seem to have made up their mind to refuse the benefits of inclusion within the Empire.” Charliss felt a distant ache in his hip joints and shifted his position a little to ease it. A warning, those little aches. The sign that his spells of bodily renewal were fading. They were less and less effective with every year, and within two decades or so they would fail him altogether…

One corner of Tremane’s mouth twitched a little, in recognition of Charliss’ irony. They both knew what the Emperor meant by that; the citizens of what had been Hardorn wanted their country back, and they had organized enough to resist further conquest.

“In addition,” Charliss continued smoothly, “this land of Valdemar is overrun with refugees from all the conflict within Hardorn and from the wretched situation before Ancar perished. Valdemar could decide to aid the Hardornens in some material way, and that would cause us further trouble. We know that they have somehow allied themselves with those fanatics in Karse, and that presents us with one long front if we choose to fight them. Valdemar itself is a damned peculiar place…”

“It has always been difficult to insinuate agents into Valdemar,” Tremane offered, with the proper diffidence. Charliss wondered whether he spoke from personal experience or simply the knowledge he had gleaned from keeping an eye on Charliss’ own agents.

From beyond the closed doors of the Throne Room came the soft murmur of the courtiers who were waiting for the doors to open for them and Court to begin. Let them wait—and let them see just whose business had kept them waiting. They would know then, without any formal announcements, just who had become the Emperor’s current favorite. The little maneuverings and shifts in power would begin from that very moment, like the shifts in current when a new boulder rolls into a stream.

“Quite.” Charliss frowned. “In fact, that Hulda creature was once one of my freelance agents in the Valdemar capital. I was rather dubious about using her again, despite her abilities, until I realized just how cursed difficult it is to work in Valdemar. As it was, her progress there was minimal. Most unsatisfactory. She was never able to insinuate herself any higher than a mere court servant’s position, and she had more than one agenda and more than one employer at the time.”

The corner of Tremane’s mouth twitched again, but this time it was downward. Charliss knew why; Tremane never knowingly worked with someone who served more masters than he.

“Why did you trust her in Hardorn, then?” the Grand Duke asked in a neutral tone.

“I never trusted her,” Charliss corrected him, allowing a hint of cold disapproval to tinge his own voice. “I trust no agents, particularly not those who are as ambitious as this one was. I merely made sure that this time she had no other employers, and that her personal agenda was not incompatible with mine. And when it appeared that she was slipping her leash, I sent an envoy to Ancar’s court to remind her who her master was. And to eliminate her if she elected to ignore the warning he represented. That was why I sent a mage, an Adept her equal, with none of her vices.”

“Your pardon,” Tremane replied, bowing slightly. “I should have known. But—about Valdemar?”

Charliss permitted his icy expression to thaw. “Valdemar is peculiar, as I said. Until recently, they’ve had next to no magic at all, and what they had was only mind-magic. There was a barrier there, according to my agents, a barrier that made it impossible for a practicing mage to remain within the borders for very long.”

“But how did Hulda—” Tremane began, then smiled. “Of course. While she was there, she must have refrained from using her powers. A difficult thing for a mage; use of magic often becomes a habit too ingrained to break.”

Charliss blinked slowly in satisfaction. Tremane was no fool; he saw immediately the solution and the difficulty of implementing it. “Precisely,” he replied. “On both counts. And that was why I continued to use her. In business matters, the woman’s self-discipline was remarkable. As for Valdemar—though they have begun again to use magic as we know it, the place is no less peculiar than before, and many of the mages they seem to have invited into their borders are from no land that my operatives recognize! Well, that is all in the past; what we need to deal with is the current situation. And that, Grand Duke Tremane, is where you come in.”

Tremane simply waited, as any good and perfectly trained servant, for his master to continue. But his eyes narrowed just a trifle, and Charliss knew that his mind was working furiously. A current of breeze stirred the tapestries behind him, but the flames of the candles on the many-branched candelabras, protected in their glass shades, did not even waver.

“Your Duchy borders Hardorn; you will therefore be familiar with the area,” Charliss stated, his tone and expression allowing no room for dissension. “The situation in Hardorn grows increasingly unstable by the moment. I require a personal commander of my own in place there; someone who has incentive, personal incentive, to see that the situation is dealt with expeditiously.”

“Personal incentive, my Emperor?” Tremane replied.

Charliss crossed his legs and leaned forward, ignoring the pain in his hip joints. “I am giving you a unique opportunity to prove, not only to me, but to your rivals and your potential underlings, that you are the only truly worthy candidate for the Wolf Crown. I intend to put you in command of the Imperial forces in Hardorn. You will be answerable only to me. You will prove yourself worthy by dealing with this situation and bringing it to a successful conclusion.”

Tremane’s hands trembled, and Charliss noted that he had turned just a little pale. How long would it take for word to spread of Tremane’s new position? Probably less than an hour. “What of Valdemar, my Emperor?” he asked, his voice steady, even if his hands were not.

“What of Valdemar?” Charliss repeated. “Well, I don’t expect you to conquer it as well. It will be enough to bring Hardorn under our banner. However, if during that process you discover a way to insinuate an agent into Valdemar, all the better. If you take your conquests past the Hardorn border and actually into Valdemar, better still. I simply warn you of Valdemar because it is a strange place and I cannot predict how it will measure this situation nor what it will do. Valdemar can wait; Hardorn is what concerns me now. We must conquer it, now that we have begun, or our other client states will see that we have failed and may become difficult to deal with in our perceived moment of weakness.”

“And if I succeed in bringing Hardorn into the Empire?” Tremane persisted.

“Then you will be confirmed in the succession, and I will begin the process of the formal training,” Charliss told him. “And at the end of ten years, I will retire, and you will have Throne, Crown, and Empire.”

Tremane’s eyes lit, and his lips twitched into a tight, excited smile. Then he sobered. “If I do not succeed, however, I assume I shall resume nothing more than the rule of my Duchy.”

Charliss examined his immaculately groomed hands, gazing into the topaz eyes of the wolf’s-head ring he wore, a ring whose wolf mask had been cast from the same molds as the central wolf of the Wolf Crown. The eyes gazed steadily at him, and as he often did, Charliss fancied he saw a hint of life in them. Hunger. An avidity, not that of the starving beast, but of the prosperous and powerful.

“There is no shortage of suitable candidates for the Throne,” he replied casually, tilting the ring for a better view into the burning yellow eyes. “If you should happen to survive your failure, I would advise you to retire directly to your Duchy. The next candidate that I would consider if you failed would be Baron Melles.”

Baron Melles was a so-called “court Baron,” a man with a title but no lands to match. He didn’t need land; he had power, power in abundance, for he was an Adept and his magics had brought him more wealth than many landed nobles had. His coffers bulged with his accumulated wealth, but he wanted more, and his bloodlines and ambition were likely to give him more.

He also happened to be of the political party directly opposite that of Tremane’s. Tremane’s parents had held their lands for generations; Melles was the son of merchants. Melles was, not so incidentally, one of Tremane’s few enemies, one of the few candidates to the succession who did not underestimate the Baron. There was a personal animosity between them that Charliss did not quite understand, and he often wondered if the two had somehow contracted a very private feud that had little or nothing to do with their respective positions and ambitions.

Melles would be only too pleased to find Tremane a failure and himself the new successor. This meant, among other things, that if Tremane happened to survive his failure to conquer Hardorn, he probably would not survive the coronation of his rival, and he might not even survive the confirmation of Melles as successor. Melles was the most ruthless of all the candidates, and both Charliss and Tremane were quite well aware that he was a powerful enough Adept to be able to commit any number of murders-by-magic, and make them all appear to be accidents.

He was also clever enough not to do anything of the sort, since his political rivals would be looking for and defending against exactly that sort of attack. Melles was fully wealthy enough to buy any number of covert killers, and probably would. He was too clever not to consolidate his position by eliminating enough rivals that those remaining were intimidated.

That was, after all, one of the realities of life in the Empire; lead, follow, and barricade yourself against assassins.

And the first in line for elimination would be Tremane—if Melles were named successor.

Charliss knew this. So did Tremane. It made the situation all the more piquant.

Interestingly enough, if Tremane succeeded and attained the coveted prize, it was not likely that he would remove Melles. Nor would he dispose of any of the other candidates. Rather, he would either win them over to his side or find some other way to neutralize them—perhaps by finding something else, creating some other problem for them, that required all their attention.

Charliss had used both ploys in the past, and on the whole, he preferred subtlety to assassination. Still, there had been equally successful Emperors in the past who ruled by the knife and the garrote. Difficult times demanded difficult solutions, and one of those times could be upon them.

The entire situation gave Charliss a faint echo of the thrill he had felt back at the beginning of his own reign, when he first realized he truly did have the power of life and death over his underlings and could manipulate their lives as easily as the puppeteer manipulated his dolls. It was amusing to present Tremane with a gift of a sword—with a needle-studded, poisoned grip. It was doubly amusing to know that Melles, at least, would recognize this test for what it was, and would be watching Tremane just as avidly from a distance, perhaps sending in his own agents to try and undermine his rival, and attempting to consolidate his own position here at court.

The jockeying and scrabbling was about to begin. It should produce hours of fascination.

Charliss watched Tremane closely, following the ghosts, the shadows of expressions as he thought all this through and came to the same conclusions. There was no chance that he would refuse the appointment, of course. Firstly, Tremane was a perfectly adequate military commander. Secondly, refusing this appointment would be the same as being defeated; Melles would have the reward of becoming successor, and Tremane’s life would be in danger.

It took very little time for Tremane to add all the factors together to come to the conclusions that Charliss had already thought out. He bowed quickly.

“I cannot tell my Emperor how incredibly flattered I am by his trust in me,” he said smoothly. “I can only hope that I will prove worthy of that trust.”

Charliss said nothing; only nodded in acknowledgment.

“And I am answerable only to you, my Emperor? Not to any other, military or civilian?” Tremane continued quickly.

“Have I not said as much?” Charliss waved a hand. “I am certain you will need all the time you have between now and tomorrow morning, Grand Duke. Packing and preparations will probably occupy you for the rest of the day. I will have one of the Court Mages open the Portal for you to the Hardornen front just after you break your fast tomorrow morning.”

“Sir.” Tremane made the full formal bow this time; he knew a dismissal even when it was not phrased as one. Charliss was very pleased with his demeanor, especially given the short notice and the shorter time in which to make ready for his departure. There were no attempts to argue, no excuses, no plaints that there was not enough time.

Tremane rose from the bow, backing out of the room with his eyes lowered properly. Charliss could not find fault with his posture or the signals his body gave; his demeanor was perfect.

The great doors opened and closed behind him. Alone once again in the Throne Room, Emperor Charliss, ruler of the largest single domain in the world, leaned to one side and chuckled into the cavernous chamber.

This would be the most enjoyable little playlet of his entire reign, and it came at the very end, when he had thought he had long since exploited the entertainment value of watching his courtiers scramble about for the tidbits he tossed them. But here was a juicy treat indeed, and the scramble would be vastly amusing.

Charliss was pleased. Entertainment on this scale was hard to come by!

2

Steam curled up from the water as An’desha gingerly lowered himself into the soaking-pool of Firesong’s miniature Vale. A Vale in the heart of Valdemar—no larger than a single Gathering-tent. I would not have believed that such a thing was possible, much less that it could be done with so little magic—yet here it is.

It was amazing how much could be created without the use of any magic at all. Most of this enchanted little garden had been put together by ordinary folk, using non-magical materials. There were only two exceptions; the huge windows, and the hot pools. The windows were not the tiny, many-paned things with their thick, bubbly glass, that An’desha had seen in all of the Palace buildings, which would not have done at all for the purpose. These eight windows, two to each side of the room, went from floor to ceiling in a single flawless triangular piece. Each had been made magically by Firesong, of the same substance used by the Hawkbrothers for the windows in their tree-perching ekeles. He had also created a magical source for the hot water for the pools. The rest, this garden that bloomed in the dead of winter, and the pseudo-ekele above it, was all built by ordinary folk, mainly due to Firesong taking shameless advantage of the Queen of Valdemar’s gratitude and generosity.

Firesong felt that if he must remain here as the Tayledras envoy to primitive Valdemar, then by the Goddess, he would have the civilized amenities of a Vale!

Valdemar. An’desha had never heard of this land until a year ago. As a child and even a young man among the Clans, he had not heard of much beyond the Walls; indeed, the only places beyond the Walls he had learned of as a youngster were the Pelagiris Forest and the trade-city of Kata’shin’a’in. The Shin’a’in as a general rule cared very little for the world beyond the Plains; only Tale’sedrin of all the Clans had any measure of Outland and outClan blood.

In some Clans—such as An’desha’s—such foreign breeding was occasionally considered a minor disgrace—not a disgrace for the child, but for the Shin’a’in parent. “Could he not draw to him a single woman of the Plains?” would come the whispers, or “Was she so unpleasant that no Shin’a’in man cared to partner her?” So it had been for An’desha, child of such an alliance—and perhaps that was why his own Clan had never so much as mentioned the lands outside the Dhorisha Plains. Perhaps they had feared that talking about the lands Outside would excite an un-Shin’a’in wanderlust in him, a yearning for far places and strange climes.

Well, I found both—without really wanting either.

The blood-path Adept who had flamboyantly named himself Mornelithe Falconsbane had never heard of Valdemar, either, until the two white-clad strangers from that land had come into the territory of Clan k’Sheyna of the Hawkbrothers.

An’desha had been a silent, frightened passenger in his own body, which Falconsbane had usurped by magic and trickery. With the Adept possessing him, he had learned just who those strangers were and something of their land. He’d had no choice in the matter, since he was a hidden fugitive within the body that Falconsbane had stolen years ago.

He should have died; that was what always happened before, when Falconsbane took a body. But he hadn’t; perhaps the reason was that he had fled, rather than trying to resist the interloper.

A prisoner in my own body… He closed his eyes and sank a measure deeper into the hot water. So odd… the memories of those years of hiding, when he had no control over the actions of his own body, seemed more solid and real than this moment, when the body he had been born into was once again his.

An’desha’s had been only the last in a long series of bodies Falconsbane had appropriated as his own. All that was required, or so it seemed, was for the victim to be gifted with mage ability and to have been a descendant of a mage called Ma’ar. If those remote memories were to be trusted, Ma’ar had lost his first life—or body, depending on your point of view—in the Mage Wars of so long ago it made An’desha dizzy to think about the passage of years between that moment and this.

He slipped down to his chin into the hot water, and closed his eyes tighter, letting the steam rise around his face. His face now, and not the half-feline face of Mornelithe Falconsbane. His own body, too, for the most part, though it was more muscular now than it had been when Falconsbane helped himself to it and tried to destroy the original owner. Falconsbane had made a hobby of body sculpting, trying out changes on his daughter before adopting them himself. He had indulged in some extensive modifications to An’desha’s body, changes An’desha had been certain he would have to endure even after Falconsbane had been driven out and destroyed.

But his own actions, risking real soul-death to rid the world of Falconsbane, had earned him more than just his freedom. Not only had he regained his body, most of the modifications had vanished when the Avatars of the Goddess “cured” him of what had been done to him.

There were only two things they could not give him again; the original colors of his hair and eyes. His hair was a pure, snowy white now, and his eyes a pale silver, both bleached forever by the magic energies that Falconsbane had sent coursing through this body, time and time again. So now, when An’desha gazed into a mirror, it always took a moment to recognize the reflection as his own.

At least I see the face of a half-familiar stranger, and not that of a beast. However handsome that beast had made himself.

The hot water forced his muscles to relax some, but he feared he would have to resort to stronger measures to release all the tension.

This place is so strange… Let Firesong wallow in being the exotic and sought-after alien; An’desha was not comfortable here. The only people he really knew were Nyara, the mage-sword Need, and Firesong, the Tayledras Adept. Of the three, the only one he spent any time at all with was Firesong. Nyara was very preoccupied with her mate, the Herald called Skif—and at any rate, it was hard to face her, knowing she was the offspring of his body when Falconsbane had worn it, knowing what his body had done to hers. Now that the crisis was over, Nyara seemed to feel the same way; although she was never unkind, she often seemed uncomfortable around him.

As for the ancient mage-sword that housed the spirit of an irreverent and crotchety sorceress, the entity called Need had her nonexistent hands full. She was engrossed in training Nyara, helping her adjust to this new land. Need was quite used to adjusting to new situations; she had been doing so for many centuries; in this, he had nothing in common with her.

After seeing changes over the course of a few hundred years, I would imagine that there is very little that surprises her anymore.

And as for Firesong—

He flushed, and it wasn’t from the heat of the water cradling him. I don’t understand, he thought, his logic getting all tangled up with his feelings whenever he so much as thought about Firesong. I just don’t understand. Why this, and why Firesong? Not that the Shin’a’in had any prejudice about same-sex pairings, but An’desha had never felt even the tiniest of stirrings for a male before this. But Firesong—oh, Firesong was quickly becoming the emotional center of his universe. Why?

Firesong. Ah, what am I to do? Is he my next master?

His thoughts circled, tighter and tighter, like a hawk caught in an updraft, until he physically shook himself loose. He splashed warm water on his face and sat up straighter.

Don’t get unbalanced. Concentrate on ordinary things; deal with all of this a little at a time. Think of ordinary things, peaceful things. They keep telling you not to worry, to rest and recover and relax.

He opened his eyes and deliberately focused on the garden around him, looking for places that might seem a little barren, a trifle unfinished. He had discovered a surprising ability in himself. It was surprising, because the nomadic Shin’a’in were not known for growing much of anything, and Falconsbane had been much more partial to destroying rather than creating when he had been active.

I never thought I’d be a gardener. I thought that was something only Tayledras did. He loved the feel of warm earth between his fingers; seeing a new leaf unfold gave him as much pleasure as if he had created a poem. Though the plants were cold and alien, in their own way they were like him. They struck a chord in him the way open sky and waving grass inspired his ancestors, and the scent of fresh greenery renewed him. An’desha had an affinity with ornamental plants, with plants of all kinds now, and a patience with them that Firesong lacked. The Adept enjoyed the effect of a finished planting, but he was not interested in creating it, nor in nurturing it. Though Firesong had dictated the existence of the indoor garden, planned the general look of it, and sculpted the stones, it was An’desha who had filled it with growing things, and given it life. In a sense, this fragile garden was An’desha: body, mind, and soul.

An’desha had not confined his efforts to the indoor garden surrounding the pools, hot and cold, and the waterfall that Firesong had created here. He had extended the plantings to cold-hardy species outside the windows, deciding that as long as the windows were that tall, there was no reason why he couldn’t create the illusion that the indoor garden extended out into the outdoors. So, for at least the part of the year when the outside gardens were still green, this could have been a shady grotto in any Tayledras Vale.

The illusion was not quite perfect, and An’desha studied the intersection of indoors and outdoors, frowning slightly. He had matched the pebbled pathway between the beds of ornamental grasses indoors and out, but the eye still saw the windowpane before the vegetation outside it. He moved to the smooth rock edge of the pool and laid his chin down on his crossed arms to study it further.

There must be a way to make the window more of an accidental interruption to the flow of the gardens, the sweep of the planting.

Bushes, he decided. If I have some bushy plants in here, and more that will outline a phantom pathway beyond the glass, that will help the illusion. With just a little magical help, he’d accelerate the growth of a few more cuttings, and he’d have them at the right height in a week or two.

If I use evergreens, perhaps I can even take the edge off the transition between indoors and outdoors even in winter.

He had worried when Firesong came up with these clever ideas that the original “owners” of this bit of property might object to all the changes. Firesong’s little home was in the remotest corner of a vast acreage called “Companion’s Field,” and the horselike beings that partnered the Heralds of Valdemar could very well have objected to their privacy being invaded. But they didn’t seem to mind the presence of the Adept and his compatriots; in fact, they had contributed to the landscaping with suggestions of their own that made the ekele blend in with the surroundings, just as any good ekele should. From outside, the mottled gray and brown stone of the support pillars blended with the trunks of the trees masking it, and the second story was hidden among the branches. Firesong had chosen this particular place after he had heard of a legend that told of a Herald Vanyel, supposedly Firesong and Elspeth’s ancestor, trysting with his beloved in this very grove of trees; after that, nothing would do but that his own ekele be here as well.

Firesong had insisted on building his “nest” in Companion’s Field in the first place, rather than in the Palace gardens, precisely because he did not want any hint of the alien buildings of Valdemar to jar on his awareness.

Strange. I would have thought that Darkwind would be the one to feel that way, not Firesong. Darkwind was a scout; at one point, he could not even bear to live within the confines of a Vale! But Darkwind dwells quite comfortably in the Palace with the Queen’s daughter, and it is Firesong who insists on removing himself to the isolation of this place.

Then again, Firesong was a law unto himself; he could afford to dictate even to a Queen in her own Palace how he would and would not live. Firesong was the most powerful practicing Adept in this strange land, and he did not seem to have a moment’s hesitation when it came to exploiting that fact. Eventually Elspeth and Darkwind might come to be his equals in power, but he had been a full Adept from a very tender age, and had a great deal more experience than either the k’Sheyna Hawkbrother or the Valdemaran Herald.

And perhaps he has isolated himself for my sake, and not his own. That could very well be the case. An’desha stared into the tree-shadows on the other side of the window, and sighed.

He, more than anyone else, knew just how tenuous his stability was. For all intents and purposes, he was still the young Shin’a’in of fifteen summers who had run away from his Clan in order to be schooled in magic by the Shin’a’in “cousins,” the Hawkbrothers. For most of his tenure within Falconsbane’s mind, he had no more than brief glimpses of what Falconsbane had been doing. He had no real experience of those years; he might just as well never have lived them. In a very real sense, he hadn’t. Most of the time he had been hidden in the darkness, snatching only covert glimpses of what Falconsbane was doing. I was afraid he’d sense me watching through his eyes—and what he was doing was horrible.

If he chose, he could delve into Falconsbane’s memories now; mostly, he did not choose to do so. There was too much there that still made him sick; and it all frightened him with the thought that Falconsbane might not be gone after all. Hadn’t he hidden within the depths of Falconsbane’s mind for years without the Dark Adept guessing he was there? What was to keep the far more experienced and practiced Adept from having done the same? He had only Firesong’s word that Mornelithe Falconsbane had been destroyed for all time. Firesong himself admitted he had never before seen anything like the mechanism Falconsbane had used for his own survival. How could Firesong be so certain that Falconsbane had not evaded him at the last moment? An’desha lived each moment with the fear that he would look into the mirror and see Mornelithe Falconsbane staring out of his eyes, smiling, poised to strike. And this time, when he struck at An’desha, there would be no escape.

Firesong was teaching An’desha the Tayledras ways of magic, and every lesson made that fear more potent. It had been magic that brought Falconsbane back to life; could more magic not do the same?

But by the same token, An’desha was as afraid of not learning how to control his powers as he was of learning their mysterious ways. Firesong was a Healing Adept; surely he should be the best person of all to help An’desha bind up his spiritual wounds and come to terms with all that had happened to him. Surely, if there were physical harm to his mind, Firesong could excise the problem. Surely An’desha would flower under Firesong’s nurturing light.

Surely. If only I were not so afraid…

Afraid to learn, afraid not to learn. There was an added complication as well, as if An’desha needed any more in his life. The first time he had voiced his temptation to let the magic lie fallow and untapped within him, Firesong had told him, coolly and dispassionately, that there was no choice. He must learn to master his magics. Falconsbane never possessed a descendant who was anything less than Adept potential. That potential did not go away; it probably could not even be forced into going dormant.

In other words, An’desha was still possessed of all the scorching power-potential of Mornelithe Falconsbane, an Adept that even Firesong would not willingly face without the help of other mages. The power remained quiescent within the Shin’a’in, but if An’desha were ever faced with a crisis, he might react instinctively, with only such training as he vaguely recalled from rummaging through Falconsbane’s memories.

On the whole, that was not a good idea. Especially if the objective was to keep anything in the area alive.

To wield the greater magics successfully, the mage must be confident in himself and sure of his own abilities, else the magic could turn on him and eat him alive. Falconsbane had no lack of self-confidence; unfortunately, that was precisely the quality that An’desha lacked.

I cannot even bear to meet all the strangers here, and it is their land we dwell in! Stupid of course; they would not eat him, nor would they hold Falconsbane’s actions against him. But the very idea of leaving this sheltered place and walking the relatively short distance to the Palace, crowded with curious strangers, made him want to crawl under the waterfall and not come out again.

So he remained here, protected, but cowering within that protection.

He found it difficult to believe that no one here would hold against him the evil Falconsbane had done. He had such difficulty facing those stored memories that he could not imagine how people could look at him and not be reminded of the things “he” had done.

And I don’t even know the half of them… the most I know are the things he did to Nyara. The truth was, he didn’t want to know what Falconsbane had done—never mind that Firesong kept insisting that he must face every scrap of memory eventually. Firesong told him, over and over again, that he needed to deal with every act, however vile, and mine it for its worth.

He decided that he had stewed enough in the hot water; any more, and he was going to look like cooked meat. There were no helpful little hertasi here in Valdemar to attend to one’s every need—a fact Firesong complained of bitterly—but An’desha had grown up in an ordinary Shin’a’in Clan on the Plains. That was a place where if a person did not do things for himself—unless he was incapacitated and needed help—they did not get done. He had brought his own towels and robes to leave beside the pool, with extras for Firesong when he should reappear, and made use of those now.

This hot pool was the mirror image of a cold one on the other side of the garden. It had a smooth backrest of sculptured rock, taller than the user’s head; hot water welled up from a place in the center of the pool, and a waterfall showered cooler water down from above, from an opening at the top of the backrest. The whole was surrounded by screening “trees” and curtains of vines; Firesong did not particularly care if someone wandered by and got an eyeful, but An’desha was not so uninhibited.

Firesong’s white firebird flew gracefully across the garden room as he climbed out of the pool and dried himself off. It landed beside the smaller, cooler pool that supplied the waterfall, in a bowl Firesong had built for it to bathe in. It plunged in with the same enthusiasm as the humblest sparrow, sending water splashing in all directions as it flapped and rolled in the shallow rock basin. When it finally emerged from its bath, it looked terrible, as if it had some horrible feather disease, and its wings were so soaked it could scarcely fly. It didn’t even bother to try; it just hopped up onto a higher perch to preen itself dry with single-minded concentration. Hawkbrothers usually had specially-bred raptors as bondbirds, but in this, as in all else, Firesong was an exception.

An’desha got along quite well with the bird, whose name was Aya; especially after he had coaxed some berrybushes the bird particularly craved to grow, blossom, and bear fruit out of season in this garden. Aya was happy here; he did not seem to miss the Vales at all.

Even the firebird felt more at home here than he did.

He recognized the fact that he was feeling sorry for himself, and he didn’t much care. The firebird paused in its preening, as if it had read his thoughts, and gave him a look of complete disgust before shaking out its wet tail and turning its back on him.

Well, let it. The firebird had never had its body taken over by a near-immortal entity of pure filth, had it?

He dried his hair and wrapped himself up in his thick robe, then went off to one part of the garden he considered his very own.

In the southwestern corner of the garden, near the window, he had planted a row of trees screening a mound of grass off from the rest of the garden. In that tiny patch of lawn he had pitched a very small tent, tall enough to stand in, but no wider than the spread of his arms. It wasn’t quite a Shin’a’in tent, and it certainly wasn’t weatherproof, but that hardly mattered since it was always summer in this garden. Here, at least, he could fling himself down on a pallet, look up at a roof of canvas, and see something that resembled home. And as long as he made no sound, there was no way to know whether or not the tent was occupied. Firesong had made no comment about the tent, perhaps understanding that he needed it, even as Firesong needed some semblance of a Vale.

A strand of his own damp white hair tangled itself up in his fingers as he pushed open the tent flap, and he shook it loose impatiently. White hair—he looked Tayledras. Just as Tayledras as Firesong or Darkwind. There was no way that anyone would know he was Shin’a’in unless he told them. Was there a reason for that? Firesong had told him it was because of the magic, but if the Star-Eyed had chosen, She could have given him back his native coloring. For a little time, at least.

He sat down on the pallet; it was covered with a blanket of Shin’a’in weaving—a gift from a Herald, who’d bought it while on her far-away rounds—and it still smelled faintly of horse, wood smoke, and dried grasses. The scent was enough, if he closed his eyes, to make him believe he was home again.

If the Star-Eyed could remake my body, couldn’t She have taken away the magic, too?

Magic. For a long time, he’d wanted to be a mage. Now he wished She had taken his magic away, but there was always a reason why She did or did not do something.

He stared at the canvas walls, glowing in the late afternoon sun coming through the windows, and chewed his lower lip.

If She left me with magic, it is because She wants me to use it for some reason that only She knows. Firesong keeps saying it’s my duty to do this, to Her as well as to myself. He felt a flash of hot resentment at that. Hadn’t he risked everything to defeat Falconsbane—not just the pain and death of his body, but the destruction of his soul and his self? Wasn’t that enough? How much more was he going to have to do?

Then he flushed with shame and a little apprehension, for he was not the only one to have risked all on a single toss of the dice. What of those who had dared penetrate to Ancar’s own land to rid the world of Ancar, Hulda, and Falconsbane? If Elspeth had been captured, she would have been taken by Ancar for his own private tortures and pleasures. Ancar had hated the princess with a passion that amounted to obsession and, given the depravities that Falconsbane had overheard the servants whispering about, Elspeth would have endured worse than anything An’desha had faced.

Then there was Darkwind. Falconsbane hated Darkwind k’Sheyna more than any human on the face of the world, and only a little less than the gryphons. If Darkwind had been captured, his fate would have been similar to the one Elspeth would have suffered. And as for Nyara—

Nyara’s disposition would have depended on whether or not King Ancar had recognized her as Falconsbane’s daughter. If he had, he would have known she represented yet another way to control the Dark Adept, and she might have been kept carefully to that end. But if not—if Ancar had given her back to her father—

She would have been wise to kill herself before that happened. In her case, it would not have been hate that motivated atrocity, but the rage engendered by having a “possession” revolt and turn traitor. Motivation aside, the result would have been the same.

As for Skif and Firesong, the former would have been recognized as one of the hated Heralds and killed out of hand; the latter? Who knew? Certainly Falconsbane and Ancar would have been pleased to get their hands on an Adept, and given enough time, anyone could be broken and used, even an Adept of the quality of Firesong.

No, he was not the only person who had risked everything to bring Falconsbane down, so he might as well stop feeling sorry for himself. Still, it hurt.

That was precisely what Firesong would likely tell him, if Firesong had been there, instead of teaching young Herald-Mages the very basics of their Gift.

Firesong… Once again, a wave of mingled embarrassment and desire traveled outward in an uncomfortable flush of heat. Somehow Firesong had gone from comforter to lover, and An’desha was not quite certain how the transition had come about. For that matter, he didn’t think Firesong was quite sure how it had happened. It certainly made a complicated situation even more so.

Not that I needed complications.

He flung himself down on his back and stared at the peak of the tent roof. How did a person sort out a new life, a new home, a new identity, and a new lover, all at once?

It only made the situation more strained that the new lover was trying to be part of the solution.