6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

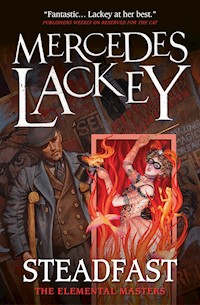

The new novel in Mercedes Lackey's bestselling series of an alternative Edwardian Britain, where magic is real—and Elemental Masters are in control. Lionel Hawkins is a magician whose act is only partially sleight of hand. The rest is real magic. He's an Elemental Magician with the power to persuade the Elementals of Air to help him create amazing illusions. It doesn't take long before his assistant, acrobat Katie Langford, notices that he's no ordinary magician—and for Lionel to discover that she's no ordinary acrobat, but rather an untrained and unawakened Fire Magician. She's also on the run from her murderous and vengeful brute of a husband. But can she harness her magic in time to stop her husband from achieving his deadly goal?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

STEADFAST

By Mercedes Lackey and Available from Titan Books

Elemental Masters

The Serpent’s ShadowThe Gates of SleepPhoenix and AshesThe Wizard of LondonReserved for the CatUnnatural IssueHome from the SeaSteadfastBlood Red

Collegium Chronicles

FoundationIntriguesChangesRedoubtBastion

STEADFAST

ELEMENTAL MASTERS

Mercedes Lackey

STEADFASTE-book edition ISBN: 9781783293971

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street London SE1 0UP

First edition: May 201412345678910

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2013, 2014 by Mercedes Lackey. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

To the programmers and developers of the late Paragon Studios, and the memory of City of Heroes, my second home.

Contents

Cover

Half Title Page

By Mercedes Lackey

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

About the Author

1

Katie Langford woke with a start, heart pounding, the sweat of terror soaking her clothing. It took her a moment of paralyzed fear to realize that she was not in the circus wagon, she was not about to be beaten by her husband again, and at least for this moment she was safe. Safe, sleeping on a sort of shelf-bed in old Mary Small’s vardo, protected by the menfolk sleeping outside. She could hear their snores from underneath her, sheltered by the great Traveler wagon, and from the bender tents around the wagon.

She took slow, careful breaths as her heart quieted, and she felt her emotions fall back into the curious state of numb apprehension that she couldn’t seem to work her way out of. She wondered if she would ever feel normal again—or happy?

Probably not until I know that Dick is dead.

She listened to the snores. Mary Small had outlived her husband, but her sons and grandsons were many, and since Mary had declared that the half-blooded Katie was to be sheltered and protected, her sons would see to it that their mother’s word was followed.

This was . . . interesting. Her mother might have married a gadjo, she might be didicoy, and Katie herself might know no more than a few words of the Traveler tongue, but still, it seemed that for Mary Small, blood was blood.

Perhaps it was something more than that, for Mary had declared she was drabarni, she had magic, and so she was to be doubly protected.

Katie could not for a moment imagine where Mary had gotten that idea. Magic? The only magic she had ever seen was sleight of hand and outright fraud. Her mother had told her stories of magic . . . but if Katie’d had anything like what had been in those stories . . .

My parents would be alive, she thought, and swallowed down tears. If I’d had that sort of magic, they would be alive.

It was dark in the wagon. The communal fire outside had been allowed to die down to banked coals, there was no moon, and they were far from a town. It was quiet, too; Mary Small was a tiny woman in robust health, and slept as quietly as a babe.

Katie breathed slowly and carefully in the spice-redolent darkness of the vardo, waiting for the tears to pass, the numbness to settle in again. It was only three days ago she had taken everything portable she had of value and fled the circus—but it seemed an entire lifetime ago. She still could hardly believe that she’d had the temerity. That Katie, who’d resolutely taken everything that was due her and run, seemed a stranger to her. After months of being married to Dick, she had turned into a terrified mouse of a creature, afraid to put a single finger wrong. Where had that courage come from? She still didn’t know . . . but it hadn’t lasted for more than the few hours it took to put some distance between her and the circus.

Once it had run out, then she’d settled into the state of dull anxiety she lived in now. But she had kept going, understanding that after having run, being caught would be—a horror. She didn’t dare even think about what Dick would do to her if he caught her.

It had been only a day since she had stumbled on the Traveler encampment—literally ran right into it, since the vardos of the Small clan were Bow Tops, painted to blend in with the woodland rather than stand out like the bright red and gold Reading vardos. The entire two days before, she had been running, mostly along country lanes and paths through forest, changing her direction at random. Her husband Dick—and more especially, Andy Ball, the owner of Ball’s Circus—would most likely assume she would head for one of the nearest towns rather than take to the countryside. They didn’t know her at all, nor had they ever made any effort to know her. They would assume she was like the other women of the circus, who knew only the wagons, the tents, and the towns.

Dick would be furious, not only because she, his possession, had dared to run from him, but because she had picked the lock on his strongbox and taken every bit of the money she had earned. Or at least, every bit that was left after his drinking; she took only what should have been her salary, and there was still money left in the strongbox when she closed it again.

It was not as if he actually needed her money. The truth was, he generally didn’t have to pay for drinks, though he was quite a heavy drinker. Locals in the pubs would buy him rounds just to see his tricks, like unbending and rebending a horseshoe, or tying an iron bar into a knot. He didn’t have to pay for whores, either, with farmer’s lasses throwing themselves at him.

She wouldn’t have cared about that. She didn’t care about that. She’d only married him because he’d been craftily kind to her after the horrible fire that killed her parents, and because Andy Ball said she had to marry a strong man to protect her now, and who was stronger than the Strong Man himself? She’d been so paralyzed with grief, mind fogged, so alone . . . Andy had been so insistent . . . it had seemed logical. Most marriages among circus folks were arranged, anyway—an acrobat daughter sent into a family of ropewalkers, or off to learn trapeze work. So she’d gone along with it, and found herself married to a man who at first was impatient with nearly everything she did, then increasingly angry with her, then who knocked her around whenever something displeased him.

Of course, it hadn’t been bad at first. A slap here, a push there—circus folk were not always the kindest to each other and plenty of husbands and wives left marks on each other after fights. Circus folk drank, and there were often fights.

She’d gone in despair to Andy Ball, who had shrugged, and said “Then take pains to please him, he’s your husband, you must do as he says. I told him if he broke your bones, he’d be answering to me, so stop your whingeing.” And for the longest time, she had believed that it was her fault. After all, her mother and father had never done more than shout at each other. And none of the other circus wives were ever treated as she was. She’d been too ashamed to talk to any of the other women about it, especially when he began to really beat her.

Why had Andy urged the marriage on her? Because Dick wanted her and he was handing her over like some reward for loyalty? Because he was afraid to lose his chief dancer and contortionist?

She’d been part of a three-man acrobatic act; her mother, her father, and herself. It had been like that for as long as she had been alive. With her family gone, besides her dancing in the circus ballet, and her contortions in the sideshow, Andy had come up with a new act for her. She became part of Dick’s strongman act, with tricks like standing on her hands while balanced on Dick’s palm, and shivering the whole time, afraid he’d drop her. She would have liked to join some other act, but Dick forbade it. “You’ll work with me or no one,” he said, in that tone of voice that made her shake and imagine that no one meant he’d strangle her in her sleep.

It was only when she’d been bathing in a stream—she usually did that alone, to hide the bruises—and some of the other women had come on her unexpectedly that she had finally been forced to confront the truth. They’d been alarmed, then angry, then—afraid. Because while, one and all, they told her that this wasn’t right, they also told her she would have to somehow get away on her own. No one dared challenge Dick. He could snap any other man’s neck without thinking about it.

At least their words had snapped her out of the fugue of despair and fear, and gave her the courage and the strength to run. The opportunity had come when a lot of rich men had descended on Dick and plied him with drink far stronger than he was used to. He’d been so dead drunk that nothing would have awakened him, giving her plenty of time to pack up all her belongings, steal the money, and get a good head start on him. As a child she’d been a woods-runner, and in summer, her parents had often spent entire weeks camped out, hidden, on someone’s private land, living off it. Unlike Dick, she didn’t need a town to survive. But she was counting on the idea that he would think she did.

It had been while she was following a path through the woods on some lord’s enormous estate that she had stumbled on the Travelers. The old woman had started with surprise as she appeared in their midst. She’d snapped out a few commands from the porch of her vardo in the Traveler tongue, and one of the young men had seized Katie’s wrist before she could run.

“Don’t be afraid,” he’d told her, in a lightly accented, warm voice that caressed like velvet. “Puri daj has seen you are of the blood. She says you are drabarni, and that you are afraid and running. We will hide you.”

The accent, and the words, straight out of her childhood, when her mother had whispered Traveler words to her, had somehow stolen her fear away—and besides, at that point she was exhausted and starving. Cress, a few berries, and mushrooms she had gathered had not done much for her hunger. The old woman had directed that she be brought to the fire, given an enormous bowl of rabbit stew, and draped with a warm shawl. She’d fallen asleep where she was when the bowl was empty. They’d woken her enough to guide her into the vardo, where she’d fallen asleep on a little pallet on the floor. When night fell, one of the women had awakened her and pulled down this shelf-bed, which she had climbed into to fall asleep immediately again. It was narrow and short, and must have been intended for a child, but she was small and it fit her.

Today she’d been given things to do—mending Mary Small’s clothing, since the old woman’s eyes were too dim to thread a needle now—and wash pots and dishes, freeing another of the women to go out and forage in the forest. The men went out and came back with food and word that the circus folk had passed through the village, asked if anyone had seen a girl like her, and moved on without stopping to set up.

“They’re in Aleford,” one of the boys, last in, had reported. “Set up there. Moving on in the morning.” He had eyed her, then. “What did you do, that made you run?”

“My husband beat me,” she had told him, the first time she had told anyone but Andy Ball, the shameful words surprised out of her. He had told her never to tell. He had told her she deserved it. Even now, it was almost easier to believe he was right, he’d said it so often.

“Ah,” the boy had said, and spat to the side. “A curse on a bully that strikes a woman, unless with wanton ways or shrewish tongue she drives him to it.”

“The drabarni is neither wanton nor shrew,” Mary had proclaimed from the porch of the vardo, though how on earth she could know anything about Katie . . .

Her words settled things, it seemed, for the boy spat to the side again and repeated his curse, without the conditions this time.

“What is it you do with the circus?” someone else asked. So far none of them but Mary had told her their names, but it was one of the four other women in this clan.

To answer that, she showed them, bending over backward and grabbing her ankles with her hands, straightening up again and going into a series of cartwheels so fast that her skirts never dropped to show her legs at all. “And I dance,” she had added simply as she finished back where she had started and clasped her hands in front of her.

“Good,” Mary had nodded. “Then you can do that while the boys play music. And we will teach you your mother’s dances. You have the Gitano look about you and we are Gitano. Now it is time to eat.”

And now she was spending her second night under the canvas top of Mary’s vardo, which seemed to be the place they had decided she was to stay. At this point she was content to do what they told her to. It wasn’t only her body that was exhausted, it was her mind.

A rumble of thunder in the distance suggested what it was that had woken her; a moment later a gentle rain pattered down on the canvas top of the vardo. There was a curtain she could use to draw across the front of her shelf, and she did so. A moment later three of the boys came up the stairs, their bedrolls over their shoulders. They squeezed themselves together on the floor, and before she would have believed it possible, they were asleep again, on their sides, arranged like spoons in a drawer.

And the rain lulled Katie back to sleep, secure in the presence of her protectors beyond the gently waving curtain.

***

Everyone said this was going to be the “perfect summer.” April had been unseasonably warm. So was May. It was now June, and quite beyond “unseasonably warm”—in Lionel Hawkins’ estimation, though he would never use such language in the presence of a lady, it was bloody damned hot.

He lounged at the stage door of the Palace Music Hall in Brighton, wondering if he should try and see if there was a sylph about willing to fan in a bit of breeze. But that would mean actually stepping outside, in his stage costume, attracting the inevitable attention of the horde of small boys lurking out there, hoping to sneak in. That would put him in the position of either having to show them a little sleight of hand to satisfy the little beggars, or scare them away with a show of Turkish Fury and a bit of flash powder. Too much work, either way.

Not with only an hour to showtime. He might get away with stepping outside if he was in the persona of Antonio Grendini or Professor Corningworth, but not as Taras Bey, the Terrible Turk.

At least the costume was cooler than most, consisting of a pair of ballooning silk Turkish pants, a wide silk sash, a vest, a turban, and nothing else but some greasepaint. Glad I still look menacing, and not like some fat carpet-seller, he thought to himself, as one of those small boys peeked in the door, squeaked, and retreated at his scowl before the doorman could chide him to step away. This was not his favorite act, but it appeared he had chosen it wisely when he’d decided who he was going to play for this season. If it got any warmer, the music hall was going to be unbearable at afternoon rehearsals for anyone in a heavy costume. He thought about the wool suits Grendini and the Professor wore, and grimaced. No. Not until hunting season, if then!

Unlike most of his kind, Lionel did not do “the circuit,” moving from music hall to music hall. Lionel remained in place, forever installed at the Palace. He didn’t change his location, he changed his persona and his act instead. This enabled him to have a house of his own, possessions that did not need to be portable, the luxury of days off that were spent enjoying himself, and the equal luxury of a cook-and-housekeeper who left a lovely dinner on the table waiting for him when he got home, saving him from eating greasy and dubious meals in pubs. It also enabled him to collect large-scale props and effects that very few other magicians outside of the great metropolises could own or use. Transporting big effects was expensive, and the risk of damage was always real. His effects all lived in his warehouse, and only needed to be moved once a season.

This settled life also meant he saved money. It was much cheaper to keep your own place than it was to live in short-term lodgings.

He had many personas, and was always creating more. There was Taras Bey, with his sword-tricks and more ways to dismember a lady than Torquemada, Lee Lin Chow who specialized in silks, doves, and Chinese cabinet effects, Antonio Grendini who performed large illusions, Alexander Nazh the mentalist, Professor Corningworth with his sleight of hand, and Saladin the Magnificent who conjured spirits and apparitions. He’d considered adding an escapist routine, but decided that at his age he just wasn’t flexible enough any more. Besides, Grendini already had one big “escape” trick, and he didn’t want to repeat it. He had also considered a mediumistic act, but didn’t like the idea of duping people into thinking he could speak with their beloved dead.

There was a smell of hot cobblestones from the alley—thankfully no worse than that. The doorman, Jack Prescott, a sturdy and upright man—if battered and much the worse for war—did a fine job of keeping people from using the area as a privy while the music hall was open. All on his own he had taken to sluicing down the area with water and a broom before everyone started arriving for rehearsals. That made things much more pleasant for everyone.

Prescott turned, as if he had sensed Lionel’s thoughts—which he might have, since both of them were Elemental Magicians; Lionel of Air, and Prescott attuned to Fire. Lionel offered him a cigarette. Prescott took it. Lighting up was never a problem for a Fire mage. Prescott was a handsome man, despite the lines that pain had carved into his face, and he was clearly still every inch the soldier. His brown hair was short and neat under his workman’s cap, his neckcloth tied with mathematical precision, his jacket, hung up on the back of his chair, unrumpled. His shirt had been ironed, and it looked as if his trousers went into a press every night.

“Did you get up to London for the coronation?” Lionel asked. Edward VII’s coronation had taken place in May, and Lionel remembered Prescott had talked about going there and meeting up with some of his old mates from his regiment.

Prescott shook his head. “By the time I thought about it, the only rooms you could get were little garret holes up three and four flights of stairs. I couldn’t face stumping up and down a dozen times a day with this.” He tapped his cane on the side of his leg, rapping the wooden peg that took the place of the limb he’d lost in the last gasp of the Boer Wars. “Not to mention what they wanted for a few days was more than I pay for my flat for a month. I shudder to think what everything else was costing, though I suppose I might have been able to eat in the regimental mess, still.” An errand boy ran up with a package. Jack signed for it.

“I’ll take that,” Lionel offered, and Prescott handed it over.

“Don’t get excited, it’s beards for the comic acrobats,” Prescott said with a grin. “Not candy for that pretty little can-can dancer.”

Lionel snorted. “My assistant Suzie is better looking.”

“Which is why she’s getting married,” Prescott reminded him. “Have you found a replacement yet?”

Lionel sighed. This was the bane of his existence. You wanted a pretty assistant, but pretty assistants had the temerity to go off and fall in love! I’d hire an ugly girl, but then I would have to cast the illusion that she was pretty—and then face her wondering why men were interested in her when she was on stage but not when off. “Not for lack of trying. She’ll stick until I do, though. She’s a good girl, Suzie is.”

“I’ll keep my eye out for you,” Prescott promised as Lionel turned to deliver the box of beards. “Sometimes a dancer turns up at the stage door looking for work, and for the Turkish act, a dancer would do.”

Not for anything else, though, Lionel thought glumly as he made his way back to the dressing rooms. He didn’t often regret his decision to remain in one place and change his act while everyone else around him was on the circuit—but in the matter of getting and keeping good assistants, his mode of life was a handicap. When a girl was only dealing with stage-door beaus, who inevitably thought she would be easy, it wasn’t so hard to keep her. Because you moved every four to six weeks, it was less likely she’d meet anyone but a lot of cads, except the lads in fellow acts. And the lads in fellow acts very often had sisters, wives or mamas that were fiercer than mastiffs at protecting their own. But when you stayed put, well, it gave her the chance to meet someone with more on his mind than improper advances. A local girl had family and friends here already, she might have had a beau or two when she’d hired on. Knowing the town, she had a lot more opportunities to meet nice fellows than someone who was transient. So far in his career, Lionel had watched a full half-dozen good assistants walk down the aisle with Brighton boys.

On the other hand, since all of them were still local, all of them kept themselves in good fettle, and all of them still kept in touch—in an emergency, he knew he could count on at least half of them to be willing to put in a few nights or even weeks in the old act.

Still, that slight advantage was far outweighed by the disadvantage. Not for the first time, he wished that he could finally get a good, permanent assistant.

And while I’m dreaming, let’s dream one that’s got some real magic in her too.

He’d had two of those; it had been blissful, knowing that he wouldn’t have to watch for some slip to betray him in his act. Lionel was more than just a stage magician; Air Magic was the magic of illusions, and his act was generally more than half real magic as opposed to stage magic. Floating and flying small objects? All done with the aid of sylphs. Levitating? His apparatus hardly needed to bear the weight of a good-sized goose, since the sylphs aided there as well. Bending and shaping the air meant he didn’t have to depend on physical mirrors. In general he didn’t need more than half of the physical apparatus of a conventional stage magician. But you had to be careful when you had an assistant who might notice that there was a lot more going on in the act than you could account for by normal means.

He squeezed his way along the narrow corridors. Space was at a premium in a theater. The more space backstage, the fewer seats up front. Finally he arrived at the appropriate dressing room. Beards delivered, he went back to his own.

As the only resident performer, his room had a well-lived-in look, and a great many more creature comforts than those afforded to the transients. As a result it was very popular for lounging, and he discovered the current “drunk gentleman comic” sprawled over his shabby but comfortable armchair when he arrived. There was a matching couch, but evidently Edmund Clay preferred to hang his legs over the arm of the chair and lean his head against the back.

“I don’t suppose you have any mint cake in that sweets drawer of yours, do you?” that worthy asked as he took his seat at the dressing table to put the finishing touches on his makeup.

Lionel opened the door with a foot. “Only hard peppermints, but help yourself.”

“Thanks.” The comedian did so. “I should know better than to eat at the Crown. I try to remind myself every time we come to Brighton, and I always forget.”

“Well, stop taking those lodgings right next to it,” Lionel told him.

“But they’re cheap and clean!” Edmund protested. “How often does one find that particular combination?”

“Not nearly often enough,” Lionel admitted. “But in this heat, you really should avoid the Crown, or you’re likely to get something more serious than an upset stomach from all the grease. Look, there’s a Tea Room about half a block north—”

“Tea Room!” Edmund interrupted him. “And sit there amid a gaggle of—”

“Do shut up and stop interrupting me,” Lionel snapped crossly. “Who is the native here, you or me? It serves cabbies. Nice thick mugs of proper strong tea, nice thick cheese sandwiches. You can’t go wrong.”

“Oh well, in that case,” Edmund replied, and set to sucking on a peppermint. Lionel went back to putting the finishing touches on Taras Bey.

There was a perfunctory tap on the door and it opened. “Lionel, are we doing the basket trick first, or the—oh, hullo, Edmund!”

“Hello Suzie,” the comic said, looking up at the pert little blond wearing an “Arabian” costume that served double duty when she worked the chorus during the Christmas pantos. “Your veil’s working loose on the right side.”

“Oh golly, thank you,” the assistant replied, and hastily refastened the offending drapery. “If I weren’t about to leave poor Lionel in the lurch it would be time to think about a new costume, I guess.”

“But you are about to leave poor Lionel in the lurch,” Lionel said heartlessly, watching her in the mirror. “So you’ll just have to keep mending it. I’m not buying two new costumes for the Turk act in one season. And yes. Basket first. Then the Cabinet. Then I saw you in half. It’s working better with the audience that way.”

“Right-oh!” Suzie said brightly, and scampered off to fix her outfit after blowing Edmund a kiss.

“Well, that peppermint seems to have done the trick—”

“For heaven’s sake, come back with me for dinner when the show’s over,” Lionel ordered. “Mrs. Buckthorn said she’s baking me a hen; I can never finish a whole one by myself, and this is no weather to go saving it for tomorrow. I’d probably poison myself.”

“Don’t have to ask me twice,” Edmund said complacently. “Right, getting on for curtain time. Break a leg.”

He swung his long legs over to the floor, got up and sauntered off. Lionel could tell from the sounds in the theater that the curtain was about to go up. He finished the last touches on his makeup, stood up, and thrust his two trick scimitars through the hangers on his silk sash.

Why, oh why, did Suzie have to get married now?

***

Jack Prescott listened to the hum of the theater behind him, and kept a sharp eye out for little boys trying to sneak in. From now until curtain-down, that would be his main task. Not overly daunting for anyone, even a fellow with only one good leg to his name. The alley out there was like an oven; even though the sun was down, it still radiated heat. If you weren’t moving, if you accepted the heat the way he had learned to in Africa, it felt good. Or maybe that was just his talent as a Fire mage talking; Fire mages always seemed to take heat better than anyone else.

He lit another cigarette and inhaled the fragrant smoke. Tobacco caused no harm to a Fire magician, who could make sure nothing inimical entered his lungs—nor to an Air magician, who could do the same. And the tobacco seemed to help a bit with the ever-present ache of his stump.

He poked his head out of the door, and looked up and down the alley. Even the little boys had gone now, discouraged by the heat, and knowing there would be no more coming and going from the door until the show ended. A real play or a ballet or some other, tonier performance would give the actors, dancers and singers a break now and then to come to the stage door, catch a smoke, get a little air. A music hall tended to work you a lot harder. Acts often had two or three different sets and had to rush to change between them. Only star turns appeared once a night. Lionel was a star turn, even though he never appeared anywhere but here; he was just that good. But his assistant Suzie did double duty in the chorus behind a couple of the singing acts for a bit of extra money, so Lionel, being the good sport that he was, did the same as well.

Jack sat down on the stool propping the door open for a bit of air, and rubbed the stump. It always hurt. He wasn’t like some fellows, he never got the feeling he still had a leg and a foot there. He didn’t know if that was bad or good. He did dream about having two legs again, sometimes . . . but except for the ache, and the difficulty in doing some things, he reckoned he wasn’t that badly off. There were others that had lost two limbs or more. Or worse, come back half paralyzed. Or blind. At least he could hold down a job—a job he liked, moreover. Alderscroft in London had arranged it when he’d come back an invalid, through the secret network of Masters and magicians. It had taken time to arrange, virtually all of the time he was in the hospital recovering and learning to walk again, but hunting for a job on his own would have taken a lot longer.

The only other magician here was Lionel, so Jack wasn’t entirely sure how the job had come about, only that the offer had turned up in the mail, inside an envelope with the address of Alderscroft’s club on it. That had been about two months after the hospital had given him the boot and he was pensioned out. At that point, he’d jumped on it; he’d been staying with his sister, but they’d never been all that close as kids, and her husband had been giving him looks that suggested he was overstaying his welcome.

He’d expected that, of course. In a way, he’d been surprised it hadn’t happened sooner. He was a lot older than this, his youngest sister, and he reckoned she had mostly offered to let him stay out of a feeling of obligation. He couldn’t move in with his older sister, the one he was actually close to—she was living with their parents, in their tiny pensioners’ cottage, and there wasn’t room for a kitten in there, much less him. They weren’t the only children, but all his other siblings were in service. He’d have been in service himself—he’d been a footman—if he hadn’t joined the Army.

And of course, no one had any use for a one-legged footman.

Behind him, he could hear the orchestra in the pits, and the reaction of the audience. Out there past the door, if he strained his ears, he could hear the sounds of motorcars chugging past on the road beyond the alley and the vague hum of the city. The heat was keeping people out later than usual. Probably, between the excitement of being on holiday and the heat, they weren’t able to sleep. Well, it was intolerable heat to them; having been in Africa, where you slept even if it felt like you were sleeping in an oven, it wasn’t so bad to him. He knew all the tricks of getting yourself cool. Not a cold bath, but a hot one, so when you got out you were cooler than the air. Cold, wet cloths on your wrists and around your neck. Tricks like that.

But if it got hotter, and all his instincts as a Fire magician told him it was going to, people would certainly die. They didn’t know the tricks. They’d work in the midday heat, instead of changing their hours to wake before dawn, take midday naps, and then work as the air cooled in late afternoon. It was going to be bad, this summer. He’d have to see if he could do anything with his magic to mitigate things in the theater. At least, he and Lionel could get together and see what the two of them could do.

He’d have to be on high alert for fires in the theater too. In fact, when he’d been hired on, that seemed to have been the chief reason he’d been taken.

“Says here you have a sense for fire,” the theater manager, old Barnaby Shen, had said, peering at the paper in his hand.

“Aye, sir. Maybe just a keen nose for a bit of smoke, but I’m never wrong, and I never miss one.” All true of course, though it was the little salamander that told him, and not his nose. That had saved his life, his and his mates, more times than he cared to count in Africa. Knowing when a brush fire had been set against them, knowing where someone was camped because of their fire . . . even once, knowing when lightning had started a wildfire and the direction it was going in time to escape it.

He hadn’t really even been a combatant, just a member of one of the details set to guarding the rail lines. The Boers rightly saw a way to be effective with relatively few men by sabotaging the rail system, hampering the British ability to move troops and resupply, and at the same time tying up a substantial number of Tommies by forcing the commanders to guard those lines.

It was a weary, thankless task, that. Kipling had got it right. Few, forgotten and lonely where the empty metals shine. No, not combatants—only details guarding the line. A handful of men to patrol miles of rail, never seeing anything but natives, and those but few and far between.

He’d cursed his luck, the luck that kept him out of real combat . . . until new orders had come down that made him grateful to be where he was.

They’d almost left him, the salamanders, when he’d first turned up in Africa, and the orders came to burn the Boer homes and take the women and children left behind to the camps. They hadn’t left only because he’d escaped that duty right up until the moment he’d gotten injured, by getting assigned to patrol. But he’d heard about the camps from other men in the hospital. Camps where half the children starved to death, or died of dysentery, and the women didn’t do much better. Fortunately—he supposed, if you could call losing a leg “fortunate”—he’d never had to either burn a home out, or drive the helpless into captivity. He hadn’t even lost the leg to a man. It had been a stupid accident that got him, a fall and a broken ankle that went septic, far from medical help. When you were on the rail detail you were pretty far from help, and his commander reckoned it could wait until the weekly train came in. So he’d waited, in the poisonous African heat. By the time he had got that help, all that could be done was to cut the leg off just below the knee, but by that time he’d been so fevered he hadn’t known or cared.

He was well out of it all at that point. He hadn’t realized just what a horror this so-called “war” was when he’d joined the Army. Hadn’t realized he’d be told to make war on women and children. Hadn’t known he was going to war for the sake of a few greedy men, and diamonds, and gold.

Hadn’t realized just how vile those men could be.

Hadn’t realized that the leaders back home hadn’t given a pin about the lives of the common soldiers they squandered. That he and his fellows were no more to them than single digits within a larger number on a marker they shoved about on a map.

He knew by the time he mustered out, though.

He was bitter about it, but he tried not to let the bitterness eat him up. There were plenty of things to be thankful for. That he’d never been forced to make war on the innocent. That he’d escaped the sickening horror of guarding the camps where his own country was murdering children by inches. He told himself that he had no blood directly on his hands, and no deaths on his conscience.

And he was grateful for this job that he had held since. The people here at the Palace were kind in their own ways. He had a decent job, one he liked, with people he liked. He had money for books, and the leisure to read them. If his magic wasn’t strong, it was at least useful.

In the end, he had it better, so much better, than some of the other shattered shells of men that had come out of that war. Yes, he had a lot to be thankful for.

And when bitterness rose in him, when his stump ached too much, that was how he burned the bitterness out. The flame was not high, but it was clean and pure. And in the end, what more could a man ask for?

2

Katie had been with the Smalls for a month now. The Travelers had supplied Katie with clothing. Walnut had stained her skin darker, and some concoction of Mary Small’s had made her dark hair closer to black. She knew all the names of everyone in the clan at this point. Only Mary and her sons and one of the brides were pure Gitano, rather than mixed-blood—which probably accounted for the reason why Katie, with her mixed blood, was welcome among them.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!