9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

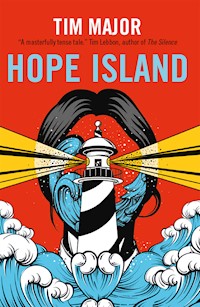

A gripping supernatural mystery for fans of John Wyndham's The Midwich Cuckoos from the author of Snakeskins. Workaholic TV news producer Nina Scaife is determined to fight for her daughter, Laurie, after her partner Rob walks out on her. She takes Laurie to visit Rob's parents on the beautiful but remote Hope Island, to prove to her that they are still a family. But Rob's parents are wary of Nina, and the islanders are acting strangely. And as Nina struggles to reconnect with Laurie, the silent island children begin to lure her daughter away. Meanwhile, Nina tries to resist the scoop as she is drawn to a local artists' commune, the recently unearthed archaeological site on their land, and the dead body on the beach...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also By Tim Major and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Also Available from Titan Books

ALSO BY TIM MAJOR AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Snakeskins

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Hope Island

Print edition ISBN: 9781789092080

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789092097

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition May 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2020 Tim Major. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organisations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Rose, this one’s for you.

CHAPTER ONE

All chatter ceased the moment Nina slammed her heel onto the brake, yanked the wheel to the left and then, as she remembered which side of the road she ought to be driving on, hard to the right. The unfamiliar Chrysler saloon groaned and shuddered but barely slowed. Its front wheels struck the dark grass bank, throwing Nina forwards. The car hissed in complaint, bumping to a lopsided stop.

Nina worked her jaw. The silence was like deafness.

‘Everyone okay?’ she said. She twisted to look into the back seat, wincing at the spike of pain in her neck.

‘Shit, Mum,’ her daughter Laurie said, her eyes shining.

Nina’s de facto mother-in-law, Tammy, was sitting in the back seat beside Laurie. ‘Lauren Fisher! We don’t appreciate that kind of language, do you understand?’ She glared at Nina, who understood the subtext: scolding Laurie ought to be Nina’s job. ‘What in heaven’s name are you doing to my car?’

Nina had swerved because there was a child on the road.

Through the grimy windscreen she could see the girl still standing in the centre of the track, illuminated by the car headlights. She stared at the car with no suggestion of alarm. She looked to be around ten years old, certainly younger than Laurie, and wore a cardigan, long socks and a pleated skirt. What was she doing out at this hour?

None of the passengers in the car had noticed the girl.

‘I think your brakes need seeing to,’ Nina said. ‘Is there a garage on the island?’

‘My Bobby never has any problem when he visits,’ Tammy replied in her loud, flat drawl. ‘He drives it like a dream.’

Nina’s knuckles whitened.

‘But Bobby – I mean Rob – isn’t here, is he?’ she said as coolly as she could manage.

Tammy removed her fur hat and placed it in her lap like a cat, then smoothed her hair which had remained unmussed despite the lurching of the car. It was held fast with lacquer, the smell of which mingled with her perfume to make the air in the car heavy and sweet. The Fishers’ scent was probably ingrained into every atom of this old heap. Tammy fussed with her handbag, tutting as she rifled through it, as if the sudden stop might have somehow robbed her as well as startled her.

Nina turned to Tammy’s husband sitting in the front passenger seat. His head was bowed as though in prayer. ‘Abram? You okay there?’

Abram raised his head, blinking in surprise. A red horizontal smudge gave him a third eyebrow in the centre of his forehead. Now the blood began to seep down at both ends of the wound.

‘Oh hell,’ Nina said. ‘Here. Let me help.’ She pulled a tissue from the inside pocket of her jacket, spilling crumpled tickets and English coins as she did so. Abram smiled as she dabbed at his forehead. The injury wasn’t as bad as it looked, only a nick from bumping against the dashboard. Abram’s old skin looked thin as paper; it wouldn’t have taken much to puncture it.

Nina sensed movement at the edge of her vision. The girl on the road. Her small body slackening, her knees buckling. The car hadn’t even come close to hitting her, but the shock of a near-miss must have terrified her. She fell to the ground; her limbs, her torso, then her head disappeared as she slipped into the gloom beyond the headlight beams.

Tammy and Laurie made protestations as Nina pushed open the door and stumbled onto the grass bank. The car pinged its soft alarm as a complaint at the door being left open.

Nina edged around the bonnet, shielding her eyes from the headlights. The world beyond the yellow light was a black ocean.

She squinted into the dark, where the girl had fallen.

‘Hello?’ she said quietly. ‘Are you there?’

She knelt to put a hand on the ground where the girl had been, then felt a fool. What was she hoping to find? A trace of heat?

‘I just want to check that you’re all right,’ she said, unsure where to direct her voice. Her words were swallowed by the darkness as soon as they left her mouth.

The wind rolling up from the harbour was as regular as breathing.

Another sound overlapped it. More breathing.

Nina turned to her left and was relieved to see that the girl was on her feet again. Only her silhouette was visible, blacker than the darkness behind her.

‘You shouldn’t have been on the road,’ Nina said. ‘Were you hurt when you fell?’

More breathing.

The girl replied, ‘I’m okay.’

Nina exhaled. ‘Do you live very near here?’ Then she remembered where she was; the island was tiny. ‘Of course you do. Would you like me to drive you home?’

She took a single step forwards. Immediately, the girl retreated a step, stumbling on the gravel.

Nina held up her hands.

‘You don’t need to be afraid,’ she said. ‘I just want to know you’re safe.’

‘Keep away,’ the girl said. ‘Leave me alone.’

Nina didn’t move. She felt desperately tired after her long journey and her many attempts to summon enthusiasm from a recalcitrant Laurie.

‘Do you want me to scream?’ the girl said, without inflection.

The breeze from the ocean snuck around Nina’s neck, making her shudder.

‘What?’ she said. ‘Why would you scream?’

‘I said keep away.’

At first, Nina’s only clue that the girl was backing away was the sound of her feet, but then she recognised that the black shape was diminishing. The girl was moving downhill, towards the harbourside. Surely there were no homes down there.

‘Look, this is silly,’ Nina said. She couldn’t let the girl continue wandering in the opposite direction to her home. ‘Won’t you tell me your name, at least?’

The girl moved faster. It was hard to be certain, but it seemed that she was still facing Nina, that she was walking backwards down the hill, though the idea seemed absurd. Nina followed, matching her uneven pace. In this stop-start manner they approached a plain building, an ugly concrete structure directly at the foot of the steep hill that hung behind the harbour.

The girl came to a halt at the corner of the concrete building. A slice of moonlight fell upon her pale face. The skin below her eyes appeared cracked and raw. She craned her neck to look past Nina. Nina turned and was shocked to realise that the car wasn’t far away – they had barely walked any distance. Inside the vehicle, Tammy and Laurie were deep in conversation. In the front passenger seat, Abram was staring at the wad of tissue in his hands.

Nina turned back to the girl, annoyance flaring within her. At precisely the same moment as Nina began to stride towards her, the girl stepped backwards again, disappearing into the narrow gap between the rear of the concrete building and the rock face at the foot of the hillside.

Nina swore softly.

‘Please come out,’ she said.

Then, ‘You’ve told me that you’re okay. So you can head on home.’

As she closed the distance to the building, she heard scuffling sounds from the narrow gap.

She stretched both arms before her, like a sleepwalker.

More scuffling. The lightest of sounds, barely anything, but becoming more frantic with each passing second.

‘It’s all right,’ Nina said, more to herself than to the girl.

She turned her head, listening for the girl’s breathing, but she heard only that same skittering sound.

She placed her right hand on the rock face, her left on the rough wall of the building. Reluctantly, she dipped her head into the gap.

The scuffling sound was amplified within the narrow passage.

Nina took a breath and eased herself fully into the gap.

But as the sound grew, so did a strong sense of the wrongness of all of this.

That sound.

It was too light, too flimsy.

The thought of pushing further into the gap was suddenly unimaginable.

‘Please,’ she said, but got no further, because the skittering sound grew louder and wilder. Something brushed against her stomach, tugging at the fabric of her T-shirt.

The need to retreat became overwhelming. She toppled backwards awkwardly, not trapped within the narrow gap but unable to turn. The loose rocks beneath her feet prevented her from launching herself away effectively, so that when some tiny, frenzied thing emerged from the depths of the darkness, batting against her forearms as she struggled to protect herself, she could do nothing other than continue to fall backwards.

Then she was on the ground, her already aching neck now singing with pain. She held her arms crossed before her face as something small and unpredictable flashed down. It nipped at her forearms then snuck past them to fling itself at her face. She gasped but didn’t cry out as some hard, sharp part of it dragged across her throat, a clean vector on her skin that she visualised as a line of bright light rather than an injury. The creature’s crackling flurry was as loud and calamitous as a cresting tidal wave.

It flittered upwards, puncturing the strip of moonlight – a panicked, skittering thing. A bird.

* * *

Tammy and Abram’s house – that is to say, Rob’s childhood home – was not as Nina had expected. She had seen photos over the years and had dismissed the white porch and its white trellis as outdated Americana, envisaging Tammy and Abram sitting before their vast homestead, glaring at their neighbours. But Cat’s Ear Cottage really was a cottage, reminiscent of the small homes on the Scottish islands Nina had visited, albeit with red cladding as opposed to slate or stone. The view from the porch was not of a neighbourhood but the endless Gulf of Maine dotted with tiny hillocks of islands nearer to the mainland. The moonlight skidded on the surface of the water, delineating the stark horizon and making Nina’s breath catch at its geometric beauty.

She dallied on the porch after the others had entered the house, scanning along the rough dirt track, wondering about the girl on the harbour road. After her absurd encounter with the bird, Nina had forced herself to return to the gap between the building and the hillside, but it had been empty – the girl must have wriggled around two walls to evade her. She was probably at home now, sniggering about having fooled some clueless Brit.

When Nina had returned to the car it was clear that not only had her passengers failed to see the girl when she had been on the road, they hadn’t seen or heard anything that had happened afterwards, either.

Laurie emerged from the cottage and tugged her arm, pulling her indoors. ‘Come inside, Mum. It’s cold out here.’

If the exterior of the house had surprised Nina with its simplicity, the interior had the opposite effect. Behind the low, brown leather furniture the walls of the wood-panelled sitting room were crammed with framed photos of Tammy and Abram on their travels. They stood before geysers and campervans and restaurants; they wore sunglasses, garish floral patterns, hats with slogans. The images were selfies from a time before selfies, reliant upon Tammy asking passers-by to operate her camera. Nina tracked the images from right to left, travelling backwards in time. Tammy’s outfits became progressively less enveloping, her skin less pale. Her hair its usual dyed caramel, then dazzling white, then merely peppered with bright flecks, then her original dark blond. Abram grew in stature, his back straightening and his creases flattening, until he stood a head taller than his wife and his eyes became Rob’s eyes, shining and laughing.

The papery Abram of today emerged from the dining room and gazed up at the photos with polite interest.

‘You’re sure you’re not hurt too badly?’ Nina said. Now the wound on his forehead looked more like a bindi or a dab of paint.

Abram turned both of his palms upwards and frowned at them. ‘Never better. It’s wonderful that you can be here, Emma.’

They had known each other for almost fifteen years.

‘Actually, that isn’t—’

Laurie yanked at her elbow again. ‘Hey, Mum. You should see your room.’

Nina frowned at Abram but then allowed herself to be led back into the hallway. She turned towards the staircase.

Laurie shook her head. ‘No, you’re downstairs. Gran calls it the den. You’ll laugh when you see it.’ She pushed open a door.

Nina didn’t laugh.

This room, too, was wood-panelled and had its walls filled with photos. But these photos were all of Rob. Here was Rob as an infant in pictures arranged alongside the den’s built-in cupboard with its slatted double doors; Rob as a child aging incrementally along a wall otherwise interrupted only by a flat-screen TV and a dartboard; Rob as a lumbering teen; and then recognisably her Rob, his laughter lines already established as his likenesses edged closer and closer to the doorway in which Nina stood. She missed him suddenly. She had an urge to slip her arms around the waist of any of the men in these pictures. Surely she had a claim over some of them? She searched for a picture of herself but found none. Judging from this display, Rob’s life had ended around the time that he and Nina had first met. Perhaps they ought to have got married, if only so that the wedding might have warranted a single framed photo somewhere in Tammy and Abram’s house.

Laurie skipped to the centre of the room, to the foot of the futon that took up most of it. She had become herself again: a fourteen-year-old as opposed to the surly late-teen she had playacted on the journey.

‘Hi Dad,’ she said as she whirled around, looking up at the photos.

‘I can’t sleep in here,’ Nina said without thinking.

Laurie stopped spinning. She tilted her head. ‘No? All right. I will, then. You can sleep up in the box room between Gran and Grumps.’

Nina shivered. It was difficult to decide which was the less appealing repercussion of switching rooms: the idea of trying to sleep surrounded by Tammy and Abram in their respective bedrooms, or the thought of Laurie sleeping down here, watched over by Rob.

‘No,’ she said hurriedly. ‘I’ll be fine down here. It’s cosy.’

‘You’re the boss.’

Nina watched her daughter carefully. That was what Reeta and Laine and the rest of her newsroom team said when they disagreed with her instructions: You’re the boss. She had told herself that with Laurie she could shed her authoritarian stance. Being on Hope Island was supposed to be an escape from all that. A new start.

It was important that Laurie felt friendly towards her, before Nina broke the news.

She flinched as something bumped against her arm.

Tammy held a tray of cookies. She peered into the den. ‘Bobby said he was coming. Not that I’m complaining, of course. It’s always a blessing having Laurie stay with us. No matter the circumstances.’

Nina took a breath before beginning her rehearsed excuse. ‘I’m sorry it’s come as a surprise. Rob had already booked the plane tickets to come here, and it would have been a waste not to use them.’

In her too-loud voice, Tammy said, ‘We’d been looking forward to seeing Bobby for forever. I still don’t understand why he isn’t here.’

‘Dad’s away,’ Laurie said. ‘He’s been away yonks.’

‘What’s a yonk?’

Laurie giggled. ‘Ages. Weeks.’

‘He hasn’t been away weeks,’ Nina corrected her daughter. ‘A week. And a bit. He sends his apologies, Tammy.’

Tammy smiled. ‘One of these days Laurie will be able to make the hop on her own, I suppose.’

‘But not yet,’ Nina said. ‘I hope you don’t mind me being here, Tammy?’

‘Why should I? Goodness me.’ She paused. ‘You’re one of the family.’

Nina noted the pause. She was certain that Tammy had almost said ‘practically one of the family’. Despite Nina’s long relationship with Rob, despite her having brought Laurie into the world, her status was still up for debate.

‘And I can’t remember if you told me – Bobby is…’

‘In the Czech Republic. Somewhere near Prague.’ It was the same lie Nina had used when Laurie had asked the question more than a week ago. She had no idea why she had answered ‘the Czech Republic’ in the first place; she had never been there. Strange how the mind worked sometimes. ‘A holiday, sort of. He’s with friends.’

‘Well, I should hope he would be,’ Tammy said with a gruesome smile. ‘What’s a holiday with people who aren’t your friends?’

Nina pressed her lips together, uncertain how much to read into the question.

She realised Laurie was watching her carefully. The image of the girl on the harbour road flashed into Nina’s mind, the face superimposed onto her daughter’s, yellow-white as though still lit by car headlights. That same baleful expression.

‘Well. Cookies are in the other room for those that can risk indulging,’ Tammy said brightly. ‘Your suitcases are still in the car. Can you manage, Nina?’

She escorted Laurie across the hallway before Nina could answer.

CHAPTER TWO

Nina slept in and jet lag turned everything inside out. She blinked sleep out of her eyes to see a hundred Robs smiling down at her. She groaned and rolled onto her face. The slats of the futon pushed through the thin mattress and dug into her chin.

Her phone gave the time as 10.30 a.m., but blearily she remembered that it would have set itself to local time automatically, and that UK time was five hours ahead. She hadn’t slept this long for a decade or more. Not that she felt any benefit. Last night, after making her excuses and turning in ‘early’, she had stared at a patch on the ceiling, trying to ignore the Robs, listening to the enthusiastic rise and fall of Laurie’s voice, the strident tone of Tammy’s, the infrequent bass rumble of Abram’s as they exchanged anecdotes in the sitting room.

Nina had an irrational sense that Laurie was being stolen away from her by Tammy and Abram, by Hope Island itself. She reminded herself that yesterday’s journey had been fraught from the off. Their booked taxi hadn’t arrived, the replacement had rolled up to their house late, the man behind the American Airlines counter had disputed the dimensions of Nina’s suitcase, and another man operating the full body scanner had detained Nina almost long enough for them to miss their flight due to a cheese knife that somehow had remained in her jacket pocket after a friend had returned it following a dinner party. The flights were long, uneventful slogs enlivened only by pilot episodes of TV shows she would never watch again and her abortive attempts to make headway with The Sound and the Fury. The stops, at Philadelphia International and then Washington Ronald Reagan, had been fluorescent-lit and bland. When they had arrived at Portland, Maine, it had taken three circuits of the conveyor belt to determine that Nina’s luggage was missing – though Laurie’s had appeared almost immediately – and then four members of staff to ponder and finally alert them to an alternative conveyor belt where, inexplicably, her suitcase had chugged around and around in a slow, solo waltz.

All of this might have been bearable. Nina had hoped that the journey would feel part of the trip, that she and Laurie would bond over the daftness of the obstacles put in their way. The whole point of Nina visiting Hope Island for the first time, after all these years of refusing invitations, was to put her daughter at ease. But Laurie had jammed in her earphones early on and had slept – or pretended to sleep – on each flight. At one point, Laurie’s phone had slipped off the armrest and into Nina’s lap; when returning it Nina had flicked on the lock screen, only to discover that no music was playing.

It was only when they boarded the ferry at Boothbay Harbor that Laurie began to come alive. On the choppy twelve-mile crossing they had gripped the white barrier side by side and Laurie had used it as a makeshift ballet barre, performing swift pliés and speaking with growing enthusiasm. She gabbled about this same journey in the past – seemingly made wonderful because of the presence of Rob in place of Nina – while Hope Island grew from a smudge on the horizon to a wide crescent, its harbour nestled at the centre and Tammy and Abram waiting at the tip of its jetty.

As soon as they were given the signal to disembark Laurie raced to her grandparents, leaving Nina to struggle with both suitcases. The roar of the ferry’s engine combined with Tammy’s accent, made even less intelligible due to her foghorn shout, meant that their hellos were a pantomime of confusion. So much for the promised peace and quiet of Hope Island. So much for the welcome embrace of what remained of Nina’s family.

Nina pulled on yesterday’s clothes and lumbered out of the den. The air reeked of bacon. She followed the smell to the dining room. Her family were sitting at the table, one on each side.

‘Moments too late!’ Tammy chirruped, still in the process of forking the last thin rasher of bacon onto her plate. She wiped the serving tray clean with a piece of kitchen roll. ‘There’s melon still left over – no, look, it’s past its best – or at least there’s oatmeal.’

‘Oatmeal would be lovely,’ Nina said, but Tammy only glanced at the kitchen without rising.

In the kitchen, Nina found a crumpled packet of oatmeal in a cupboard. When she shook it, it rattled hollowly. She sighed and tossed the packet in the bin below the sink.

When she rose, movement outside the window caught her eye. She thought of the bird that had attacked her and she reached up to touch the graze that ran across her throat. It didn’t hurt, and when she had checked in the mirror last night she had struggled to make out the line.

She pressed her hands on the cold sink and leant over it, peering through the grimy glass.

At first she saw nothing amongst the dense bushes beyond the scrubby cottage lawn. It was only when the figure shifted its position again that she identified its contours, its bare arms, its eyes peeping through the leaves.

It was a child. Could it be the same girl?

Before Nina could make out any further details, the figure retreated. The window was single-glazed, thin enough for her to hear a high-pitched laugh from outside.

Back in the dining room, she slumped into a chair and helped herself to coffee from the pot. Abram attempted to pour her cream from the jug. He frowned as she put her hand over the top of her cup, then instead poured it into his own empty cup and sipped it.

‘The children seem to roam quite freely here,’ Nina said, not quite managing an offhand tone.

Laurie raised an eyebrow as she munched a slice of toast.

‘You should have left your preconceptions back in the UK,’ Tammy replied. ‘Kids here are wholesome. They enjoy simple pleasures.’

‘The girl yesterday that I told you about. She was out very late. And she acted kind of strangely.’

‘You said she gave you a shock?’ Tammy said, though without any suggestion of sympathy.

‘Well, not exactly. I tried to check on her, but a bird surprised me. I feel silly about looking so rattled by something so tiny. It must have been nesting behind one of the buildings at the harbour, I guess.’

Abram came to life. ‘What did it look like?’

Nina blinked. ‘I don’t know. Small. Mottled wings, as if they were dusty. Black patch on the top of its head.’

He nodded enthusiastically. ‘Blackpoll warbler. Should be nesting up in the woodland, never on the coast. It has this lovely song.’ He raised his chin, then released a series of high-pitched tsi sounds.

Without understanding why, Nina shivered. But she would have preferred the bird making its call rather than that panicked rush of tiny beating wings. The sound echoed at the back of her mind even now.

‘How are you feeling, Mum?’ Laurie said.

Nina felt a pang of shame at her daughter’s almost maternal concern. ‘Bit fuzzy. You don’t have any jet lag?’

Laurie shrugged. ‘I never have. Dad doesn’t either. He says it’s made up, like homeopathy.’

Rob never seemed to fall ill or experience ailments of any sort. By willpower alone he staved off jet lag, colds and hangovers.

‘Ever since I was a kid, I’d always get ill on the first day of holidays,’ Nina said. ‘Your grandparents – your othergrandparents, the ones you never met – were teachers. I think it’s genetic.’

She wished her own parents were still alive, to provide Laurie with an alternative template for adulthood. They had been good people, but frail. They hadn’t even stuck around to see Laurie born.

Laurie smiled. ‘You realise that’s the first time you’ve said that word? Holiday, I mean.’

‘That’s ridiculous.’

‘It isn’t. You’ve been calling it a sabbatical.’

Nina felt acutely aware of Tammy watching their exchange. ‘Well, it is. A month off work is a big thing, you know.’

‘It is for you.’

Nina’s executive producer hadn’t so much as raised an eyebrow when she had requested the time off. ‘About time,’ he had said with a grin. A month off would hardly make a dent in the holiday entitlement she had accrued over the last five years.

Tammy raised her eyebrows. ‘A month? My word.’ She raised her voice to speak to her husband. ‘Do you hear that, Abram? We’ll have Laurie with us for a whole month. We can celebrate Easter together at the Sanctuary, how wonderful. That’ll show narrow-minded folks what’s what.’

This was exactly the sort of discussion Nina had hoped to avoid. She had successfully avoided the subject of religion during their previous encounters, and had instructed Rob to remain vague if Tammy ever enquired. Confessing to atheism might drive a permanent wedge between her and Tammy. Despite everything, she would prefer to have her on her side. It would help in the long run.

‘No,’ she said forcefully.

Tammy’s eyebrows lifted higher still. ‘No?’

‘We’ll be staying for no more than a week.’ Long enough to drop the bombshell and then escape.

Laurie threw down her slice of toast. ‘Mum, but you said—’

‘I said we’d still be coming to Hope Island, and here we are. But I had the idea that we’ll travel around a bit, see more of Maine and maybe other states too.’

Tammy sat up straighter in her chair. ‘Hope Island is America at its finest, I guarantee you that. The grand, great outdoors, honest people, real food, none of your McDonald’s and In-N-Outs. You’ll find nothing in New England to rival one of Si Michaud’s lobsters.’

‘I’m sure you’re right,’ Nina said, ‘but I want Laurie to see more of the world.’

When Nina had discovered the flight booking printout in the cabinet on Rob’s side of the bed, her plan had seemed so clear. She wasn’t coping, and this opportunity ticked every box. She could escape from the bustle of work and the city, reconnect with the real world, come to terms with everything that had happened recently, spend enough time with Laurie to soften the blow when she delivered the news. Hope Island was important to Laurie, a safe space. Being here would lessen the impact. As a bonus, there was always the chance of Nina establishing some kind of a relationship with Tammy and Abram before giving them the lowdown on what a shit their son really was.

However, in the days leading up to their departure from Salford, the instinct to evacuate Hope Island at the first opportunity had become stronger.

‘I’m right as rain here on the island,’ Laurie said.

Right as rain. Since when did a fourteen-year-old use a phrase like that?

‘I do like an In-N-Out burger,’ Abram said thoughtfully. His upper lip still bore a stripe of cream. ‘If anyone’s going.’

Tammy rolled her eyes. She reached across the table and grasped Nina’s hands. In a tone more like an announcement than conversation, she said, ‘So it’s settled then. You’ll stay with us until Eastertime. Exciting!’

Nina withdrew her hands and sipped her cold coffee. She nodded noncommittally. When she finally mustered the courage to tell Tammy that her perfect son Bobby had abandoned his partner and his firstborn child, Tammy would be stunned, weakened, and more than happy for Nina to get out of her sight.

But things had to be in the right order. Laurie must be told first. She had to hear the truth from her own mother.

‘It’s Sunday, isn’t it?’ Nina said, genuinely uncertain. ‘Tammy, will you be busy attending a service this morning?’

Tammy’s forehead became a collection of tight wrinkles. Distantly, she said, ‘Bobby could have been a choirboy if he’d wanted. The most beautiful voice, as a child.’

Abram began humming a hymn that Nina couldn’t place. It grew louder and louder as Abram fidgeted with something below the table.

Nina clung to her line of reasoning. ‘So, Laurie and I will head off after breakfast, just the two of us.’

Tammy began clearing away the dishes. ‘No. I mean, there aren’t any Sunday services on the island.’

‘Oh.’ Nina looked to her daughter, trying to appeal to her silently. ‘Still, I’d enjoy it if you’d give me the tour of the island, Laurie. It’s my first time here and I know it’s meant a lot to you over the years. I’d love to see the place through your eyes.’

Laurie shrugged. Good enough.

‘Don’t mind us,’ Tammy said. ‘Feel free to use the cottage as a base camp. You’ll show up when you get hungry.’

Nina would have to learn the cues that signalled Tammy’s true emotions – she had no idea whether her tone indicated nonchalance, offence having been taken, or a vindictive streak. How many times had she met Tammy and Abram in the past? Four, five? But all the meetings had been brief and scrupulously polite, and all had been in England during European tours that culminated in visiting Rob. Nina had only met them once since Laurie had been born; she had been away during Tammy and Abram’s final jaunts. Then, following Laurie’s sixth birthday, Rob had begun carting her all the way over to Maine each year and Nina had always managed to make her excuses.

Abram leant over to his granddaughter. ‘Hey, watch this,’ he said. He wafted the napkin from his lap to cover an empty eggcup on the table before him. When he pulled it away again, an egg had appeared. Laurie grinned, then frowned in concentration as Abram held up a hand. With the restraint of an orchestra conductor, he tapped at the tip of the egg with a butter knife. Then he prised away its uppermost part and daintily retrieved a plastic dinosaur from it.

‘Grumps, that’s brilliant!’ Laurie lifted and peered at the egg, which seemed to Nina to be otherwise normal and untampered-with. She paraded the plastic dinosaur around the table, roaring.

Rob had always done magic tricks like that for Laurie too – he must have learnt them from Abram. Until now Nina had never thought to wonder how much preparation went into these sorts of illusions.

* * *

Hope Island was only two miles across at its widest point, but the woodland along its central spine made the journey from west to east coast slower than Nina expected. The breeze made the air colder; she chided herself for wearing a skirt. Laurie strode ahead, clad sensibly in denim, swiping at red spruce with a stick and knocking cones to the forest floor.

‘We’re nearly there,’ Laurie called over her shoulder.

Nina jogged to catch up. When she returned to Salford she would reactivate her lapsed gym membership. Too much standing around at work, then consecutive Netflix addictions in the few waking hours at home. Rob had always been careful not to flaunt his healthy social life – his evenings out at the snooker club or the pub – and had always understood about Nina being so tired after work.

‘Nearly where?’ she said.

Her question became redundant as they pushed through a final boundary of foliage and suddenly the world fell away before them.

Beyond the cliff, the Atlantic was a vast, uninterrupted plane and the sky its mirror. Nina remembered something she had once been told about ancient civilisations having no word for the colour blue, instead using terms like ‘wine-looking’ or ‘shield-like’. At this moment neither the ocean nor the sky appeared blue, even though objectively she perceived that they were dazzlingly so. Instead, they were twin voids.

She was struck by the thought that this trip might really be a positive turning point. The water sighed and the wind caught at her jacket, and she imagined her problems as dandelion seeds on the cusp of being blown away. The outside world was larger than it appeared on the monitors of her TV newsroom. There was beauty in it.

Without turning from the ocean, Laurie snaked her right arm around Nina’s waist, drawing the two of them gently together. They were almost the same height. Nina wished that Laurie had inherited her dark hair, or that she herself could be granted the same tightly curled blond hair as her daughter. She wished that they were more identifiably family.

There was no sense in waiting. This was the ideal moment. The revelation about Laurie’s father abandoning her would be put into perspective, measured against the scale of the ocean.

‘Did you know there are three Hope Islands?’ Laurie said, interrupting her thoughts.

‘What?’

‘Dad says there are millions of islands off the coast of Maine. And three of them are called Hope Island. Isn’t that funny?’

It didn’t seem at all funny to Nina. A strange idea occurred to her: that each of the alternative Hope Islands might be dedicated to only one of the wonky trinity comprised of her, Rob and Laurie. Clearly, this Hope Island belonged to either Rob or Laurie. It wouldn’t be kind to her.

She tried to shake off the feeling. ‘Laurie. I’m happy that we have some time together.’

Laurie squeezed her tighter. ‘Yep. Come on. You wanted me to show you around.’ She shrugged herself free and darted towards the cliff edge.

‘No!’ Nina yelled.

Laurie spun around at the precipice. ‘Don’t be silly. It’s nowhere near as steep as it looks.’

Nina followed and sure enough, the ground sloped away shallowly to the bare rock. What she had assumed was a cliff was actually a pile of huge boulders that appeared frozen in the act of tumbling down to the water’s edge.

Laurie had already begun to make her way down, sliding gracefully on her bottom to land lightly at the next level of boulders.

‘And your father lets you do this?’ Nina called out.

‘He never said either way. Isn’t that an American thing? Don’t ask, don’t tell?’

Nina shuffled to the edge of the first boulder and slid down, copying her daughter’s route precisely. Her bare thighs rubbed painfully against the pitted stone.

‘Where are you taking me?’ She pointed down to the waves hurling themselves at the sea-level boulders. Each one connected with a slap. ‘We’re not going all the way down there.’

‘No, we aren’t.’

Instead of clambering any further down, Laurie hugged a boulder to her left and then edged sideways along a flat, narrow outcrop. Below it the piles of rocks were less staggered, producing a sheer drop. Soon she was out of sight.

‘Laurie?’ Nina whispered.

‘Still here,’ Laurie replied, her voice made small by the rock barrier.

A few moments passed before Laurie screamed.

Nina lost her footing immediately. She grabbed at the rock behind her but couldn’t find any purchase. She yelped as her flimsy sandal caught in a fissure.

‘Laurie!’ she shouted. ‘Laurie!’

Her daughter’s scream became something deeper, something thick and drawn up from deep within her body. Nina fumbled her way along the same slim outcrop, her belly pressed against the stone, not looking down.

Laurie’s shouting continued uninterrupted. Dimly, Nina noted that it still came from the same location; Laurie hadn’t fallen any further down.

The outcrop narrowed to a point. Now Nina realised that there was no longer anything pressing against her stomach. She bent awkwardly to examine the rock she had sidestepped around to discover a cave-like depression and, within it, her daughter. Laurie peered up at her impishly. She stopped screaming.

‘What the actual fuck was that about?’ Nina snapped.

‘Sorry. It’s just what I do.’

‘Is it? Screaming like a lunatic is what you do?’

Laurie fluttered a hand to wave Nina away. ‘There isn’t room in here for two. Go back around and I’ll follow you. Then you can have a go.’

Lacking any other option, Nina obeyed. Within seconds Laurie reappeared, navigating the outcrop with ease.

‘Go ahead, Mum.’

‘I’m not doing that. And what were you doing, anyway?’

‘Primal screaming. It’s ace. I used to call this place the Crow’s Nest, because I liked pretending to be on lookout, but these days I like it for the… what’s the word? Not echo, exactly. Acoustics. Try it?’

The rising inflection was meaningful: a request more than an invitation. This was a personal thing. Perhaps it was the way to earn Laurie’s confidence.

Nina made a show of huffiness. ‘If you absolutely insist.’

Once again, Nina worked her way around the outcrop, then rotated her body carefully and eased herself backwards into the depression Laurie had vacated. The outcrop path disappeared from view. All that she could see was sea and sky.

Vertigo was something she had heard about but had never experienced. Now it was as if she slumped forwards on an axis without having moved, and suddenly the hidey-hole became a vertical tunnel, and she was hurtling towards the flat solid slab of the ocean, and in her panic she wondered whether she would crack through its surface and plunge into its depths, or whether she would skim like a flat pebble far away and out of sight. She braced herself against the uneven walls of the cave, pushing and pushing to prevent herself from being sucked into the vortex.

She pushed and shook and cowered in silence and then heard Laurie’s faraway voice say, ‘Now scream.’

Her daughter’s voice reoriented her. The ocean plate swung to become horizontal. Her stomach lagged behind, coffee swilling in its emptiness.

Now scream.

Nina opened her mouth, wondering if she would do it. The air was thick with salt and the wind spiked directly into her throat and her lungs.

The ocean sighed its disappointment.

‘I don’t want to scream,’ she said.

‘Everybody needs to let rip sometimes. You’re on your own now.’

Nina hesitated. ‘What did you say?’

‘Pretend I’m not here. It’s only you and the big wide sea. Scream and let it all out, Mum.’

Nina opened her mouth wide again, but then gagged. Abruptly, hot tears stung her eyes. She stared out at the void and thought of the note from Rob she had discovered on the kitchen table upon returning from work: I’m sorry, but I’ve gone for good. She thought of her frantic looting of the house while Laurie was staying at a friend’s house overnight: Rob’s passport gone, and maybe a few items of clothing and a couple of books, but pretty much everything else left behind. Her careful repositioning of every disturbed item the next morning in preparation for Laurie’s return. Her glassy denials to her daughter, and at work, and to her friends, that anything was wrong.

If she could only channel it all. A single scream. It would solve nothing, but it might establish an outlet. A statement of intent that she was ready to start afresh.

No sound came from her mouth. She grabbed her knees and rocked, bumping her shoulders on the hard cave walls.

Minutes passed without any sound other than the waves, a hum made somehow threatening in its journey into the cubbyhole, a roar in all but volume. She rubbed her forearm across her face, more and more rapidly as if she might prevent the tears with heat.

She struggled forwards and made a crouched one-hundred-and-eighty-degree turn in the opening of the little cave. After she had made her way along the outcrop and onto the relative safety of the boulder platform, she found that she couldn’t meet her daughter’s eye.