9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

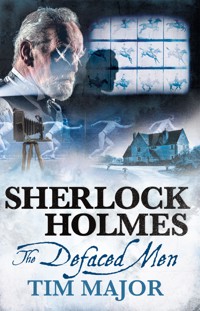

Sherlock Holmes delves into the world of early cinema as motion picture groundbreaker Eadweard Muybridge begs him to solve a mystery that will keep you up all night… It is 1896. A new client at Baker Street claims he's being threatened via the new art of the moving image… Eadweard Muybridge, pioneer of motion picture projection, believes his life is in danger. Twice he has been almost run down in the street by the same mysterious carriage, and moreover, disturbing alterations have been made to his lecture slides. These are closely guarded, yet just before each lecture an unknown hand has defaced images depicting Muybridge himself, which he has discovered, to his horror, only as he projects them to his audience. As Holmes and Watson investigate, a bewildering trail of clues only deepens the mystery, and meanwhile, newspaper speculation reaches fever pitch. The great detective's reputation is on the line, and may be ruined for good unless he can pick apart a mystery centred the capturing, for the first time, of figures in motion, and the wonders of the new cinematograph.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TIM MAJOR AND TITAN BOOKS

Snakeskins

Hope Island

Sherlock Holmes: The Back to Front Murder

THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

Gods of War James Lovegrove

The Spirit Box George Mann

The Patchwork Devil Cavan Scott

The Thinking Engine James Lovegrove

A Betrayal in Blood Mark A. Latham

The Labyrinth of Death James Lovegrove

Cry of the Innocents Cavan Scott

The Legacy of Deeds Nick Kyme

The Red Tower Mark A. Latham

The Devil’s Dust James Lovegrove

The Vanishing Man Philip Purser-Hallard

The Manifestations of Sherlock Holmes James Lovegrove

The Spider’s Web Philip Purser-Hallard

Masters of Lies Philip Purser-Hallard

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Defaced Men

Print edition ISBN: 9781789097009

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789097016

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: August 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Tim Major 2022. All Rights Reserved.

Tim Major asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Brian and Naomi

CHAPTER ONE

I have known my friend Sherlock Holmes for fifteen years, and consider my understanding of him as full as any single person on this earth. However, I must confess that much of his private life – which is to say, almost the entirety of his life, as he is nothing if not private – is yet unknown to me. Consequently, the instances of Holmes greeting a visitor to our rooms as an old friend are few. (A notable example of this phenomenon was in ‘The Case of the Haltmere Fetch’; my account of which begins with an encounter with a childhood friend of Holmes’s, but which I have no plans to publish due to the great sensitivity of the matter.)

What I mean to say by this preamble is that if Sherlock Holmes greets a visitor warmly I am minded to take particular notice, in the hope of gleaning some speck of detail that might be added to his biography.

In the mid-morning of 16th March 1896 we were working at our own desks: I compiling notes on one of Holmes’s previous cases, and Holmes occupied intently on an unknown task, writing furiously in a jotter. We might not have spoken until luncheon had we not been interrupted by the ring of the doorbell. I heard the tread of several pairs of feet up the stairs, then our housekeeper opened the door to our rooms.

“A client for you, Mr. Holmes,” Mrs. Hudson said. “A Mr—”

Her words were cut off abruptly as the white-haired man she had escorted upstairs pushed past her and into the room. Our housekeeper folded her arms over her chest in exasperation and stared at the intruder’s back, then flinched as a second man eased his way past her, carrying a heavy wooden crate, and moved to stand at one side of the room.

“Thank you, Mrs. Hudson,” I said hurriedly. When scorned, our housekeeper’s annoyance is liable to manifest in other ways, and she had promised steak pie for lunch.

She grimaced at our visitors again, then left and closed the door with more force than necessary.

I turned in my seat as the white-haired man strode to the centre of the room, looking about him as though the furnishings and hanging pictures were of equal interest as the two human occupants. On closer inspection, I saw that he was not as elderly as he had at first appeared. Though his hair was bushy and wild, and his pointed beard equally as white, and long enough to almost entirely obscure his necktie, his skin was relatively smooth and his eyes alert and intelligent. He wore a good suit and waistcoat, and beneath his arm he carried a large leather portfolio.

His eyes passed over me, then fixed upon Holmes.

“I have come to seek your assistance.” His voice was halting, as though this was the first time he had spoken to-day, and his accent was difficult to place.

Holmes watched him for several seconds, then leapt from his seat to shake the newcomer by his hand.

“My word!” he exclaimed. “You’re just the person I need!”

I paid close attention immediately, waiting to see what our visitor’s response might be. His face was a picture of confusion, but to his credit, he bowed his head politely and said simply, “Oh? How is that?”

Holmes gestured to the jotter on his desk. “I am currently preparing notes on a monograph relating to the uses of collodion – not only the more conventional uses, but also in the cleaning of lenses, in theatrical make-up both as a fixing solution and to simulate wrinkled skin when allowed to harden, in blasting gelatine, and also its potential use in the treatment of warts. It is a wondrous material, is it not? And you would be ideal in advising about one of the historical aspects of my treatise, namely the importance of the differences between wet-plate and dry.”

To add to the mystery of how the men knew one another, I understood very little of what my friend had said. I glanced at the second visitor, who seemed content to guard in silence the wooden chest he had placed on the floor beside my desk. He appeared to be in his late thirties, and wore round spectacles.

The white-haired man nodded stiffly. “I would be happy to impart what knowledge I have, in due course.”

Holmes had the good grace to let the subject drop. “You have come about another matter, of course. Please, sit and tell us all.”

As our guest sat before the fireplace, I rose and took my usual chair and Holmes took his. The white-haired man was unhurried, and did not speak. Instead, he gazed around the room again, then at Sherlock Holmes, a faint frown upon his face. Then he rose nimbly, went behind Holmes’s armchair, lifted my friend’s prized Stradivarius – I gasped involuntarily – and then he simply placed it down again, several inches to the right from its original position. On his return to his seat he similarly adjusted a lamp upon the dining-table. He sat and his eyes travelled around the room again, but now he appeared content.

Holmes watched all of this strange behaviour placidly.

“Excuse me,” I said, “but am I to take it that you know one another already?”

The visitor replied, “No, but it seems that we are both aware of the other’s features. Your newspaper caricatures are as ugly yet revealing as my own, Mr. Holmes.”

Bemused, I turned to Holmes, who shook his head. “I am not in the habit of reviewing ironic commentaries, and any details to be gleaned from caricatures are decidedly second-hand. No, I recognised you not from your face but from other salient details.”

“I have heard much of your gift for observation,” our guest said with a nod of satisfaction. “Please, explain.”

Holmes tapped a finger against his lips. “I may as well proceed in the order that details presented themselves to me. Your right eye is the first indication of your trade – or rather, the brow above it, which is considerably more lined than above the left, which indicates long hours spent squinting, or looking into a lens of some description. The same applies to many seamen who habitually use telescopes or sextants, but your manner otherwise is entirely unlike a sailor’s. I noted next that your eyes moved around the room in constant observation, and at the same time your mouth twitched as though determining some features to be to your satisfaction and others an outright annoyance. Then you spoke, and in your accent I detected English – fundamentally so in the vowel sound ‘o’ in ‘come’, indicating that you were brought up in the southern regions of this country – and then, layered upon that, hints of more than one American accent: a harsh ‘a’ in ‘assistance’, indicating time spent in the vicinity of New York, and yet at the same time, a softened ‘t’ which suggested exposure to the accents of the west coast.”

Although I had seen this sort of trick performed many times over, the fact that Holmes could draw so much from a single uttered statement still seemed a miracle. However, our guest merely nodded and waited for Holmes to continue.

“Then there is the matter of the object you were carrying,” Holmes continued, indicating the leather portfolio which our visitor had now leant against the side of his chair. “Its size is notable, of course, but what was more immediately arresting was the pasted paper on its upper corner.”

The white-haired man frowned and raised the portfolio, which was evidently heavy, onto his knees. He and I both looked closely at the traces of paper that Holmes described, which had been mostly removed, leaving only faint hints of lines.

“It is clear that it once displayed a circular design,” Holmes said, “and within that an image of a tower of some sort. It is a seal related to one institution or another – but which? The only text legible is in the upper-left segment of the circle, and appears to read ‘SITAS PEN’, which can only lead to one conclusion.”

“I am most impressed,” our guest said.

I cleared my throat. “Apologies… what is the institution, then?”

Holmes replied before I had even finished speaking; he must have anticipated my question. “The circular text once read ‘Universitas Pennsylvaniensis’, and the unusual tower is a tower of books. It is, of course, the seal of the University of Pennsylvania. But what is of most interest is that the scuffs and weathering of the leather binder suggests that it has been in regular use for at least fifteen years, yet the particular design of this seal is an iteration which has been in use only during these last… let me see… eight years – and the tearing of the pasted paper has been performed imperfectly at a much more recent time.” He looked up at the ceiling and sighed. “And then I am bound to confess that my knowledge of public figures played a part in moving from this set of general observations to a conclusion about your precise identity.” Hurriedly, as though this confession about possessing some degree of general knowledge might amount to an admission of cheating, he added, “Though subsequently I noticed the attention you paid to the movements of both my companion and I as we moved from our desks to these chairs, and I flatter myself that this may have provided the final clue even if I had not known of your personal history.”

With that, our guest pushed himself up from his chair again, and approached Holmes to shake his hand.

“It is a great pleasure to find myself in the company of somebody so attuned to the appearance of things,” he said.

Holmes’s satisfied expression evaporated. “I am occupied with the meaning of things, not simply their appearance.”

“As am I, as am I.” The man returned to his seat, and when he sat his posture was like that of a schoolboy eager to learn.

For my part, I shifted uncomfortably in my seat. There is always a point during Holmes’s parlour tricks when his audience loses its patience.

The white-haired man turned to me. “Mr. Holmes has correctly diagnosed my travels from England to America, with long periods spent on both the east and west coasts. And he has correctly identified that I may be considered both a man of the arts and a man of science – the mise-en-scène of any setting is as much of interest to me as the precise, measurable movements of the creatures within it, despite the latter having effectively become my trade.” He reached out to offer his hand. “I know that you are Holmes’s biographer, Dr. Watson, and my own name is—”

“Muybridge!” I cried out, staring at the man’s outstretched hand without shaking it.

He bowed his head and withdrew his hand. “Eadweard Muybridge, at your service.”

“I have seen a number of your photographs of human figures in motion,” I said. “They are much admired among the medical profession, as they reveal a great deal about the workings of the muscular structure that remains invisible to the naked eye, and which is impossible to determine when the body is at rest. And also… that is to say, I am sure that your pictures have much to offer artists, too, as you have suggested.”

I sensed that my cheeks were reddening as I saw in my mind’s eye the pictures I had been shown of women going about everyday tasks; those series of sequential pictures revealed ever more about the women’s movements due to the models being entirely naked. I now recalled that they had been shown to me not in the company of fellow doctors as I had intimated, but at my club.

“Art was certainly my initial calling,” Muybridge said thoughtfully, “though for many years now my specialism has been considered to be the sciences. People have taken to calling me Professor – quite incorrectly, I hasten to add.”

Holmes said, “And I maintain that your expertise in photographic techniques will prove invaluable to my study of collodion. But of course you did not come here for that purpose. Now, Mr. Muybridge, tell us of your trouble.”

Muybridge’s expression darkened. He glanced at the man at the side of the room, who remained as silent and implacable as ever.

“I fear for my life,” he said.

“Ah.” Our guest’s pronouncement had changed Holmes’s manner only very slightly: I saw his eyes shine.

Muybridge rose halfway from his seat, at the same time tugging at his white beard. “You appear to care little for my plight, sir!”

I interjected hurriedly. “Sherlock Holmes is simply accustomed to hearing each potential client’s circumstances in full before giving a response.” I did not add that fearing for one’s life was hardly an unusual circumstance for visitors to our rooms.

Muybridge lowered himself into his seat again. “I apologise. I am quick to anger nowadays. I seem to suspect everyone of malice towards me.”

My smile seemed to disarm him even further. “Please, continue,” I said.

Our guest nodded. “I returned to London in 1894, following a most successful venture at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago the previous year—”

Abruptly, he stopped and looked up at Holmes, who merely raised an eyebrow.

Muybridge sighed. “My intuition is that it would be folly to lie to you, Holmes, or even to characterise my actions in a misleading manner. Chicago was no sort of success, and the gate receipts were hardly enough to recoup the cost of the hall constructed to house my galleries and my lectures. Visitors had more hedonistic pursuits in mind; the wax museums and hoochie-coochie dancers did roaring trade.”

“Then your return to England is something of a retreat?” I suggested.

“A calculated change of emphasis,” Muybridge replied sharply. “I have little interest in vying with cheap entertainments to catch the eye of the masses. I am a serious man, Dr. Watson, and my legacy will be one of advancement of knowledge, not gaudy frivolity.”

I nodded and my eyes met Holmes’s. We had many times encountered men of a particular age, preoccupied with their lasting legacy. Such self-centred pride had been the downfall of more than one of them.

Muybridge continued, “Since then I have divided my time between two tasks. The first is the selection of images and composition of notes for a popular book dedicated to my studies in animal locomotion.”

“Then widespread readership is yet your aim?” I asked mildly.

Our guest bristled. “Anybody with information to divulge wishes to do so to the widest possible audience. What I have to show is of interest to any right-minded person, as evidenced by the fact that very many have already subscribed to the publication in anticipation, more than a year before its advertised publication. I wonder whether either of you gentlemen might be inclined to—” He broke off, and his cheeks flushed, the first appearance of colour on his face. “My apologies. I am not here to act as a salesman. I will continue with my account. The second of my recent occupations is the conducting of a number of lectures on the same subject, in various towns around this country and addressing a variety of audiences. The crowds are not as large as once they were, but their appreciation is sincere. Since October last year, this second activity has occupied more of my time and is due to conclude this very month, March.”

“Then this concern for your own well-being is connected to your lecture tour?” Holmes asked. For the first time I saw him look directly at the silent man who must be Muybridge’s assistant.

“Yes – and an even greater fear is that the conclusion of the tour may put my pursuer into a new mode, that perhaps all that has happened is only a prelude to something greater.”

Holmes nodded. “Perhaps now would be the moment to explain the nature of this ‘pursuit’.”

Muybridge turned to his assistant and nodded curtly. At once, the other man became all activity; he hefted the chest closer to the dining-table and began unpacking a collection of bulky objects of wood and brass – the first a box on stilts, the second a device with a small wheel handle on one side that appeared to operate a much larger wheel on its rear, and the third a pedestal upon which was unmistakably a focusing lens. I watched him with interest as he began to make minute adjustments to the relative positions of the items. Though this man was far younger than his employer, his hair was already thinning and the shoulders of his shabby black suit were strewn with flakes of skin.

While this had been going on, Muybridge had lifted his heavy portfolio onto his knees and unfastened the straps that held it closed. Now, with great care, he removed from the binder a large, circular glass plate perhaps fifteen or sixteen inches in diameter. Upon the plate were inscribed a sequence of drawn images of a horse. He stood and moved to the table, holding the glass plate before him as if it were a ceremonial object.

“You are no doubt aware of the zoopraxiscope which has made me famous,” Muybridge said, and I detected a change in his tone to a more authoritative address that he presumably deployed during his lectures. “As you see, it comprises a projector connected to a lantern.” To demonstrate his words, his assistant opened the side of the box on stilts and revealed the lantern within, which he promptly lit. Muybridge continued, “The projector and lens are just as one might find in a magic lantern used in any phantasmagoria show. However, the unique aspect is this central housing that holds glass plates such as this one, along with a shutter disc, which rotate in opposite directions in order to project one single image at any given moment, producing the effect of animation.”

Almost reverently, he placed the circular plate into the similar-shaped housing on the rear of the wooden box with the wheel handle. His mute assistant checked the fit, then darted to the curtains at the windows, drawing them closed. I looked at Holmes, who appeared unaffected by the liberties being taken within our home.

“Of course, it is the photographs themselves that are truly remarkable,” Muybridge went on. “They have been captured by a bank of twenty-four cameras positioned in a line, each device triggering moments after its neighbour in order to record the precise motion of the animal subject as it passes. The images are striking when viewed in isolation, but my zoopraxiscope allows me to return that animal subject to motion in a perfect simulacrum of life.”

Another nod, and the assistant crouched to work the handle and I saw the disc at the rear begin to spin. Once he had achieved a certain regular speed, he stretched out to remove a cover from the focusing lens. Immediately, an image appeared on the darkened wall of our room. Or rather I should say that it was a series of images – yet that was not how I perceived it at all. There upon the wall the silhouette of a horse galloped without moving from its position. Its limbs were a complex, overlapping mesh of activity, its mane and tail rippling like liquid, its rider bracing against the motion, far less supple than the beast he sat astride.

I had heard about the phenomenon of projected moving pictures, of course, but an example of it had not been set before me until now. I found myself quite breathless at its magic.

“I have your recently published brochure titled ‘Descriptive Zoopraxography’,” Holmes said pleasantly, “but long before that I was highly interested in your photographs of the horse named ‘Sallie Gardner’, and those later ones of ‘Occident’. To have proved that all four legs of a galloping horse leave the ground at once is a capital discovery, and one which I have drawn upon in my own work on occasion. You have provided a great service in proving what the eye cannot see.”

I looked again at the miraculous horse in motion. As Holmes had stated, between the flick of the front hooves and the rear hooves there was a moment during which the silhouetted beast and rider appeared suspended above the ground, delineated by a horizontal shadow.

Despite my appreciation of this marvel, I felt bound to say, “But these are drawings, not photographs.”

Muybridge’s cheeks reddened. “It is a limitation of the technology at hand – silhouettes are required, and fine detail would not be transferable to the plate or visible to the viewer. But each individual image is painstakingly copied from the photographic image, with amendments to ensure greater fidelity rather than corruption of reality.” He waved to his assistant, who stopped his turning of the handle and replaced the lens cover. Muybridge took from the device the glass plate and indicated one of the horse drawings inked upon it. “See that each picture is unnaturally elongated, but only in order to appear correctly proportioned to audiences due to the distorting effect of projection.”

“I do understand,” I said, rather resenting having become the focus of this lecture. “It is not a far cry from the zoetropes that children enjoy so much.”

I saw Muybridge’s body stiffen, and I realised I had made a gross error.

“My dear fellow,” Muybridge began, his eyes filled with sudden fury, “my invention is no more like a zoetrope than a living, breathing beast is like a stuffed toy. The zoetrope is a plaything, whereas the zoopraxiscope is a tool that will promote scientific understanding of the world around us. I suggest that you—”

Holmes interrupted him. “Is there another glass plate that you would like to show to us?”

For several seconds, Muybridge did not respond. Then all of his anger seemed to ebb away in an instant. Our guest was so quick to rage, which then left him with equal speed, that I began to wonder about his state of mind.

Muybridge slid the plate into a paper sleeve, replaced it within the portfolio carefully, then removed another.

“This sequence is one of my many studies of human locomotion, conducted at the University of Pennsylvania,” Muybridge said.

The images on this new plate depicted a man striding from left to right. Despite the images being drawn rather than photographed, the artist had succeeded in conveying the figure’s bushy beard and lean frame, and the thinness of his silhouetted limbs suggested he was naked.

“I myself was the model for this series,” Muybridge said.

Perhaps there was even more of the artist in this man than I had realised. Few scientific men of my acquaintance would offer themselves naked for study, but in the artistic world perhaps this was an everyday occurrence.

“May I?” Holmes said, and took the plate from our guest. Then he turned it slowly before him, crudely animating the sequence. “I take it these scratches are the cause of your anxiety?”

“Yes, they are the principal issue,” Muybridge replied.

As I gazed at the glass plate, and my friend’s face which was visible through its translucent portions, at first I saw nothing amiss. Then, as Holmes turned slightly, the light from the window glanced at a different angle, and I saw the scratches to which Holmes had referred. I rushed to stand behind Holmes’s armchair, and from this new angle the lines became far more visible. Above seven of the fourteen silhouettes were the rough letters ‘RIP’ carved directly into the glass surface. The letters grew larger on successive appearances. The smallest message hung above the head of the figure, but by the fourth iteration the feet of the letters touched the hair of his head, and by the seventh the letter ‘I’ bisected the man entirely. Still more alarming, though, was the realisation that the figure itself had not escaped mutilation. A flurry of cross-hatched lacerations made a violent cloud over each and every instance of Muybridge’s face in profile.

“And these scratches,” I said, addressing Muybridge, “I suppose they are clearly visible when projected?”

Without reply, Muybridge took the plate from Holmes and placed it into his zoopraxiscope device. His assistant turned the handle, then took away the lens cover once again.

Despite having seen the defaced plate, I was unprepared for the effect of the images when projected. The fourteen images took perhaps only three seconds to be shown in their entirety, so the sequence had already repeated several times before I was able to take in the chaotic vision. The letters ‘RIP’ grew rapidly like a cancer before beginning anew, and the consequence of the letters having been inscribed only on alternate images was a pronounced flickering that was in great contrast to the fluidity of the other parts of the animation. I found it almost impossible to concentrate on the walk of the naked Eadweard Muybridge as opposed to the shifting mass of scored lines that obscured his face, and which suggested the violence of the hand that had made them.

“As you can well imagine, the effect upon my audience was one of mingled horror and excitement,” Muybridge said.

“And the effect upon yourself?” Holmes prompted.

Muybridge frowned. “Dismay. Frustration.”

“Earlier, you referred to fear,” Holmes said.

“A turn of phrase. I fear very little. I have trekked the mountains of Yosemite and dangled above precipices in order to secure the images I require. I have wrangled wild animals. I have—” He stopped.

Now it was my turn to frown. From the newspapers I knew a little of the man’s personal history and his past actions, of which some aspects were decidedly unsettling. I pledged to speak to Holmes about the matter at the first opportunity.

Holmes went to open the curtains. Then, when the young assistant had slowed the rotation of the device to a halt, Holmes plucked the glass plate from it, ignoring Muybridge’s obvious anxiety at it being handled. Holmes examined the disc for some time before concluding, “The perpetrator worked quickly, but not in a great rush. After each letter is a small letter ‘x’ – presumably a dot was too difficult or too subtle a character to etch in such a way – but they could simply have been omitted and the effect would have been much the same. Presumably you have interviewed your staff about the matter?”

The young man who had operated the zoopraxiscope did not look up, but instead busied himself dousing the lantern and packing up the device.

Muybridge nodded. “This example is only the first of the defaced slides. After this occasion – which I discovered at an informal lecture at a club near to my home in Kingston upon Thames – I fired my assistant who had been operating the lantern. However, then it occurred at the very next lecture: a crude noose appeared around a motionless portrait of myself seated beneath the ‘General Grant’ sequoia tree of Mariposa Grove in California. I am unable to show you the evidence of that vandalism, as I smashed the glass plate shortly afterwards.”

I found it remarkably easy to imagine this white-haired man bellowing in anger and casting the glass slide to the floor, producing shards that perhaps endangered the front rows of his audience.

“Do you have any suspicions as to the author of these defacements?” Holmes asked.

“None.” Muybridge waved a hand at his assistant, whose head was bowed to his work. “You’re naturally suspicious of Fellows here, but he has no reason to have committed this vandalism, and as I have already said, he was engaged only after the first occurrence.”

“At any rate, do you have any inkling as to the purpose of the threats?”

Muybridge shook his head. “No demand has been made. Whoever did this appears to wish me ill, but wants nothing.”

“Might not professional rivalry be the inspiration?” I asked.

“It might. I have had rivals in the past, though none who might have stooped so low. But nowadays there are only disappointments…” Muybridge stared at the glass plate that Holmes still held before him, and I recalled his account of his disillusionment and failure at the Chicago exposition. “Nowadays it is more difficult to contemplate such a thing.”

I was about to question him further on this subject, but Holmes said quickly, “We understand you very well.”

“All the same,” Muybridge said, appearing grateful to move the conversation along, “these are not hollow gestures. There have been physical attempts on my life on two occasions.”

“Indeed?” Holmes said as he passed back the glass plate. His tone was as casual as if Muybridge were describing his holiday plans.

“Twice this year I have been almost run over in the street by horse-and-carriages,” Muybridge said. “And before you state that such a thing is not so unusual… both times the carriages were empty, and the driver so wrapped up in scarf and hat as to be unidentifiable to the least degree. I am convinced these were attempts on my life, so you can appreciate why I take these other threats seriously.”

“Where did this happen?” I asked.

“In Kingston upon Thames in each case, once close to my home and once directly outside the library where I often go to conduct research.”

Holmes clapped his hands together. “Well, you certainly have my attention, and I will do my utmost to help you. You said that your lecture tour is almost at an end – which is the next engagement?”