Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

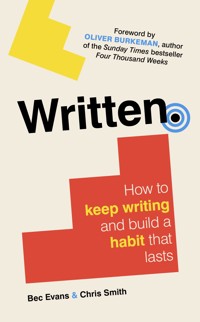

**WINNER OF THE STARTUP INSPIRATION CATEGORY OF THE 2020 BUSINESS BOOK AWARDS** 'It's impossible to read this book without being inspired and energised ... Essential reading for any start-up or entrepreneur, at any stage of the journey.' - Alison Jones, Host of The Extraordinary Business Book Club podcast and author of This Book Means Business 'Genuinely fresh and jargon-free' - Financial Times How to Have a Happy Hustle shares the secrets of innovation experts and startup founders to help you make your ideas happen. If you're looking for fulfilment outside the day job, have an idea but don't know where to start, or are held back by a lack of confidence, experience, time or money, Bec Evans will help you get off the starting blocks with this complete guide to making your ideas happen. There's no getting away from it - hustling is hard work - but with practical tools, inspiring stories, science-backed research and guidance every step of the way, you'll find what makes you happy as you build your side hustle.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

‘Hustle’ is a strange word. It used to be most commonly associated with aggression, illicit activity (to hustle money from someone), or with levels of great activity (the hustle and bustle of a city). As with so many words, however, popular culture has chewed it up, and spat it out as something else.

I started my first business when I was still, basically, a kid. I was fourteen and had started building websites in my spare time for local businesses. I just picked up a phone book and tried everything I could to get a deal, and eventually that business grew into an international company which spun out a number of other businesses. This all happened while I was going through my teens and early twenties. For me, hustle was simply the act of getting shit done – it was the process of having an idea, taking it to market and learning how to make it happen (usually on the fly)!

It’s strange that in recent times the word ‘hustle’ has turned into something toxic. Social media is full of so-called influencers who tell people to get up at some ungodly hour, never rest, always work and party hard. The problem is that this is not hustle – it’s stupidity. It’s a caricature of a warped fantasy of business – depicting a life that would burn out even the most resilient person.

Don’t get me wrong, business is hard. Running your own business or having a side gig is time-consuming, at times soul-destroying, and stressful. However, running your own business can be one of the most profoundly satisfying and stimulating careers, even if – as is the reality – the overwhelming majority of business owners don’t get rich from their venture, and a large number ‘fail’. (Neither of these outcomes is a reason not to start in the first place …)

So much commentary on entrepreneurship and business today is based on the outcome – how they ‘made it’ – rather than the process. This overlooks a very important aspect: the possibility of having a happy hustle.

Bec Evans has built a career out of helping people make their ideas happen. In this book she takes us on a journey from having ideas to polishing them up to making them a reality. This may seem unremarkable in a business book, but what is remarkable is that Bec focusses on how to build your idea, have a side gig or develop a startup without harming yourself in the process. This book is filled with real-world examples and commentary from founders and experts, and is built on a sturdy skeleton of philosophies and positive psychology – it urges us to remember that fulfilment comes from striving, not from the end result.

Over the past decade, I have been lucky enough to mentor hundreds of startup and scale-up entrepreneurs, many of whom have succeeded, and many of whom haven’t – such is the roll of the dice in business. Disappointingly, I have also met hundreds more who had seemingly great ideas and passion who never made it over that first hurdle. As Bec herself says: ‘Making ideas happen is hard, and when 90 per cent of startups fail, it’s far easier to daydream and never take the risk …’

I hope many more do take the risk thanks to reading How to Have a Happy Hustle. Ultimately, it’s businesses big and small that make our economies work and generate the innovations that improve our societies each and every day.

My advice? Get reading, and get hustling.

Vikas Shah MBE

CEO, Swiscot Group

INTRODUCTION

TO BE HAPPY

At school, when asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I replied that I wanted to be happy.

Not a helpful response for my teacher who was desperately trying to organise my Year 10 work placement. As a result, while my friends were channelling career goals by pulling on disposable gloves at the vets or chasing copy deadlines at the local paper, I spent the week working in a carpet shop. Unable to sell carpets, fit underlay, or do anything remotely useful, I failed to gain any adult life skills that week, though I did have a laugh with the carpet fitters.

Would that make me happy? It’s the sort of question that has bothered philosophers for millennia. Take nineteenth-century thinker John Stuart Mill, who wrote that happy people are those:

‘who have their minds fixed on some object other than their own happiness; on the happiness of others, on the improvement of mankind, even on some art or pursuit, followed not as a means, but as itself an ideal end. Aiming thus at something else, they find happiness by the way.’1

What Mill means is that the fulfilling kind of happiness – not the wave-your-arms-in-the-air-like-you-just-don’t-care hedonistic kind, but the stuff that will keep you going long term – doesn’t happen when you aim for it. Happiness happens when you’re doing something else, ideally something with a purpose. While office banter passes the time when you’re trapped in a daily drudge, the frequency of workplace giggles isn’t the kind of happiness that keeps us engaged in our work. Stop wasting time and instead make some art, build something or help others.

HUSTLING YOUR WAY TO FULFILMENT

Many of us want to do and be more. We want to have ideas, create something new, go beyond the confines of our job and start something of our own.

Researching this book, I asked people why they wanted to get their ideas into the world. What surprised me was that most didn’t want extra cash, to gain new skills for a promotion or to leave their current job, or even to start a new business. Instead, the top reason given – by a long shot – was self-fulfilment (otherwise known as happiness).

What would I tell my teenage self, kicking her heels in a carpet shop? I’d tell her this: while being happy is a laudable aim, it will escape your clutches if you reach for it alone. True fulfilment only comes as a byproduct of doing something which stretches you. I’d tell myself to find a side hustle.

Helping you find your hustle is what this book is all about.

If you have a vague ambition or an inkling of an idea, pursue it, even if it might fail, because you’ll find happiness along the way, often in ways you weren’t expecting. This book is for you if:

You dream of having ideas but don’t know how to start.You have the beginning of concept but got stuck making it happen.You imagine fulfilment lies beyond the 9–5 career-track but don’t know where to look.You have an aspiration for a side hustle or startup but lack the confidence, skills, time or money.HOW TO HAVE A HAPPY HUSTLE

I’m not going to sugar-coat it. Making ideas happen is tough – that’s why it’s a hustle. Hustling involves time, effort and hard work, often done as a side project alongside your other commitments.

Even if you have a corker of a concept, it’s tough developing it and getting it into the world, and when it’s there, it might not find a market. If you’re hankering for startup success, you’re best placing your bets elsewhere as the odds are stacked against you – the sad fact is 90 per cent of startups will fail.

The point of a happy hustle is not that it’s hard (there are enough startup books about that) but that trying to make ideas happen will give you great pleasure and fulfilment.

There are five principles that underpin a happy hustle:

1. Dream big but start small. Ambition is great – it gets us out of bed in the morning and striving for more. But without a plan, your dreams can come to nothing. You have to start. And by starting small you bypass the fear centres of the brain, lower the stakes, and are more likely to rack up the wins that will keep you motivated, positive and moving forward.

2. Don’t fall in love with your idea. Founder bias can blind you to feedback and keep you forging ahead with a failed plan when the evidence tells you to quit. Instead, fall in love with the problem your idea solves. Fall in love with the people who have the problem and the customers who use your solution – they will guide you to a better idea.

3. Ship before you’re ready. Forget perfectionism – you don’t have the time or money to keep tinkering. Make something and get it out to people quickly and often. Think of each version as an experiment to gather data to inform what you’re doing next. By having tight feedback loops you learn fast and improve your idea as it takes shape in the world.

4. Connect with others. Working in isolation is the worst thing you can do for your idea’s survival. So, find friends and peers who can support you, early users who can test and feed back, communities of people who are interested in what you do, and networks of people on a similar journey. Relationships will help you and your idea thrive.

5. Focus on the process not the outcome. Most ideas will fail, so don’t aim for a narrow end point of success. As you build and test your idea, learn from the experience, notice what you enjoy, reflect on what works and what you’d like to do more of, seek out engagement, and be motivated by what excites, challenges and stimulates you. And when things go wrong, you’ll have the resilience to keep going.

These approaches will help you overcome the barriers many of us face when starting something. They will help you start, build momentum and keep going. You just need to start.

SO, WHAT’S STOPPING YOU?

You might be thinking: it’s all well and good taking small steps and learning along the way, but how the hell am I going to find the time?

You’re right, your life is full of important and urgent things to do. ‘Busy’ doesn’t even describe the demands on your time and attention. To fit a side project into your schedule you must make the time. That isn’t easy. It involves saying ‘no’ to nice offers, setting boundaries, and reprioritising what’s in your schedule so there’s space to make things happen.

Let’s dive in with a quick exercise. Think: how do you currently spend your time? Look back on the past week and consider what’s getting your attention or, even better, log your day-to-day activity as you do it to build up an accurate picture. Then, imagine you could re-live that week bearing in mind your current commitments. How would you reorganise your schedule? What different choices would you make with your time? Were there opportunities you missed to work on your idea? Hindsight is indeed a wonderful thing.

With that knowledge in mind, let’s look ahead. Plan when you can make time. Grab your calendar or draw a weekly schedule like the one below:

Fill in days across the top and your normal waking hours down the side.Block out all the times you are already committed to things like work, childcare, exercise.What’s left? Are there any opportunities? If yes, book in some idea time.Not found any time? Reschedule other tasks to free up time. What can you stop doing or delegate? Can you get up earlier, go to work later? This is tough, but you can do it.Commit to your schedule. Book time for your idea like any other appointment and don’t get distracted.The internet is full of self-proclaimed productivity gurus sharing their secret to making time; often it involves getting up at the godforsaken hour of 5am. Great for them, but it might not work for you, your family and your well-being.

No one knows how long it will take you to make your idea happen – just as your idea is unique, so is your approach to creating it. The goal is to make progress regularly, so don’t worry about project planning just yet, and instead build momentum bit by bit.

I’ve found four distinct time patterns to how people move their passion projects and side hustles ahead.

The daily doer has a regular routine, often working in the same time and place, to nudge forward their idea.The scheduler looks ahead a week or two and blocks time into their calendar. They take a realistic and practical approach to planning and getting things done.The spontaneous hustler grabs any opportunity as it appears, making the most of delayed trains, cancelled meetings and sleeping children.The binger’s life is chock-full, so instead of a daily or weekly hustle, they binge every month or so on uninterrupted deep work, a progress-making day or days that are as productive as they are rare.There is no one-size-fits-all approach to making time; the important thing is just to do it. Don’t feel bad when you really don’t have the time, but make the most of when you do. You’ll surprise yourself by what you can achieve, even when you’re feeling tired and uninspired. While common sense suggests that you create best when you’re at your most alert and awake, researchers have found the opposite, saying that: ‘tasks involving creativity might benefit from a nonoptimal time of day.’2 Perhaps those internet gurus were right about 5am after all?

Now you’ve found some time, read on to get the inside track on what to do and how other people have done it.

This book shares tried and tested techniques from my work in business innovation to turn you into an ideas machine. I’ll guide you step by step with super-practical advice to build your skills and confidence as you make things happen. The book uses my experience turning a side hustle into a startup, alongside stories of founders who have led the way, so you can learn from others’ success – and failures. It is supported by expert advice and research-backed tips on how to make the most of the process.

I’ll show you how to be happy as you work to make your idea happen, regardless of whether your idea fails or takes off.

Let’s get to it. It’s time to hustle.

Notes

1 Mill, John Stuart. Autobiography, Project Gutenberg, 2003. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10378/10378-h/10378-h.htm

2 Wieth, Mareike B. and Zacks, Rose T. ‘Time of day effects on problem solving: When the non-optimal is optimal.’ Thinking & Reasoning, Vol. 17, No. 4 (2011), 387–401, https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2011.625663.

1 Having ideas

CHAPTER ONE

Problems

It all started, much like every other day, with Jo Caley getting dressed. That fateful morning, she put her foot through the knee of her favourite pair of jeans, ripping them beyond repair. Her jeans were wrecked but she was about to discover her big idea – and it all began with her hatred of shopping.

‘I was gutted,’ she says. ‘I’d have to spend hours traipsing around the shops feeling inadequate, that nothing fits me, and I can’t afford anything that I like.’

To avoid the misery of the high street, Caley decided to buy her jeans online, but the more websites she searched the more confusing it got.

To understand why she hates shopping, take a peek inside her wardrobe. Open the doors and you’ll find clothes ranging in size from a UK 6 to 14. Perhaps she’s got an issue with her weight, perhaps she’s a yo-yo dieter? No, her weight and figure have been consistent for years. Caley’s real problem is that in one shop she’s petite but when she goes to another shop she’s pushing large. Each retailer uses a different set of measurements to clothe her same-sized body. And it’s not just interpretation of sizing standards, there are a whole bunch of alternative systems including UK, US and European sizes; small, medium and large options; waist measurement and leg lengths; and then there are shops with their own unique numbering systems.

But, in the midst of her jeans shopping nightmare, her despair turned into curiosity. ‘I realised my problem, and then I thought, this is quite interesting. This must be really annoying for everybody, not just me.’

Caley was right. She realised she was part of a much wider trend. Nearly 60 per cent of British women struggle to find the right size clothes.3 Caley had encountered ‘vanity sizing’, a problem that millions of women face.

‘Poor bloody women,’ she tells me. ‘Who has time to find a pair of jeans that not only fits them, but fits their budget, that they like the look of, and does everything else that they want a pair of jeans to do?’

She was determined to help. But before we hear about her solution, let’s spend a bit more time with her as she stands half dressed, holding her torn jeans, feeling annoyed and upset.

WHY PROBLEMS?

Caley was in the right place to have an idea.

Before you fling off your clothes and wait for inspiration in your underpants, let’s find out what that means.

Y Combinator is the largest and most successful startup accelerator in the world. It has helped thousands of people turn their ideas into fast-growing technology businesses worth millions, and its investment portfolio includes big names like Airbnb, Reddit, Dropbox and Stripe. Its co-founder Paul Graham has simple advice for generating ideas:

‘The way to get startup ideas is not to try to think of startup ideas. It’s to look for problems, preferably problems you have yourself.’4

Caley had a problem. She found out other people shared it, and she got super interested in solving it. She did all of that before spending any time generating ideas or finding solutions.

The best way to have an idea is to start with a problem. The best way to find problems is to get curious.

Throughout this book, you will meet people with inspiring side hustles, founders who turned dilemmas into successful startups, professionals who problem-solve for clients every day, and idea-makers who help people to design and create solutions. Together, we’ll crush the myth of the lone inventor – because no one plucks fully formed ideas from some mysterious place in the sky. Instead, you’ll get a team of advisers with expertise and advice to turn you into an ideas machine.

BE CURIOUS

Have a problem? Don’t fret. Be curious instead.

Curiosity will help you hunt down problems and keep you interested as you explore them and decide which one to focus on. Once you’ve found a problem, you’ll generate solutions that people want, need and will pay for.

So, let’s get problematic. Over the coming chapter, you’ll:

Stop waiting for inspiration.Become a problem seeker and find what’s bugging you.Choose the most exciting problem.Finish up with a problem statement.DON’T WAIT FOR APPLES TO FALL

Archimedes had a burst of inspiration – a world-changing, knowledge-creating, scientific breakthrough, an idea so fantastic and urgent he leapt out of the bath and ran naked down the street, shouting ‘Eureka!’ – the ancient Greek for ‘I have found it!’ Archimedes hadn’t found inspiration in the bath tub, but a solution to a problem he’d been desperate to solve.

History is packed full of neat inspiration stories like Archimedes’ Eureka moment – take Sir Isaac Newton and his apple-inspired gravity discovery. Beware these myths of invention.

‘Don’t wait for the proverbial apple to fall on your head. Go out in the world and proactively seek experiences that will spark creative thinking. Interact with experts, immerse yourself in unfamiliar environments, and role play customer scenarios. Inspiration is fuelled by a deliberate planned course of action.’5

So say David and Tom Kelley, two brothers on a mission to democratise creativity. They trash the myth of a lone creative genius and instead build people’s confidence to seek inspiration through an active approach. They have made the process of invention their lives’ work, championing human-centred design. David founded D-School at Stanford which, alongside his other founding organisation, the design agency IDEO where his brother Tom also works, has trained a generation of designers around the world to solve problems big and small. Anyone, they believe, can be a creative problem-solver, you just need to start.

Most people talk themselves out of having ideas. They dissuade themselves from starting side hustles. They stop themselves from building businesses. They tell themselves they aren’t that sort of person, they don’t have the right skills or experience.

You are the right person. You have the right skills. What you’re interested in is important, and that puts you in the perfect position to make things happen. I’m going to make sure you have the best advice to get started.

I asked Jenn Maer, who works with the Kelley brothers as senior design director at IDEO, how we can begin. ‘It’s not so much a process as much as it is a way of looking at the world,’ Maer says. ‘Keeping an open, creative and optimistic mindset is incredibly important if you want to create change. You have to believe that something can be different before you can actually make it different.’

The creative mindset is a curious one, that wants to see, try, do and learn something new. We all know the advice about taking time away from our screens to take a walk, talk to people, go to an art gallery, or read a magazine or book. So far, so vanilla. I asked Maer what she recommends.

‘Look at some weird shit,’ she says. This means explore things that challenge you, stimulate your thinking and make you happy. Don’t have an agenda – because having an agenda is what kills you.

Agendas are everywhere, in our daily routines and habits. Here’s a simple exercise to squash agendas and trigger new experiences: change your morning routine.6 You could, for example, shake up your work commute by changing transport and cycling instead of getting the train, getting off the bus a stop earlier and walking, driving a different route, or listening to a different podcast or playlist. A small change to your routine can make you see things differently; it will put you in a position of curiosity because you won’t be able to rely on your habitual way of engaging with the world.

Getting out of your comfort zone can lead to new discoveries. The research backs this up. Angela Duckworth, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, writes that:

‘interests are not discovered through introspection. Instead, interests are triggered by interactions with the outside world. The process of interest discovery can be messy, serendipitous, and inefficient. This is because you can’t really predict with certainty what will capture your attention and what won’t.’7

Take Jo Caley. Her interaction with her jeans was certainly messy and inefficient – she stumbled serendipitously in her jeans and ripped her way to an interest. Vanity sizing wasn’t something she knew about, or cared about; if you had asked her about it before her jeans incident she might have said she didn’t want or need to solve the problem, but once she had experienced the problem, started digging into it, she was hooked.

You can’t predict how or when you will find a problem that interests you, but you can open yourself up to spot them. Here’s how to be a problem seeker.

WHAT’S YOUR PROBLEM?

Life is full of annoyances.

You get up, burn your toast at breakfast, and wait to board a late-running, overcrowded commuter train whose route is beset by Wi-Fi blackspots; the lack of signal drives you to read the free daily paper over the shoulder of a seated passenger, in which you discover reports of climate collapse, dwindling natural resources and the extinction of species.

Our world is full of flaws. Embrace that imperfection – it will be fuel for your ideas. Tap into your frustration to find problems you care about and want to solve.

Start with what’s bugging you now. Problems hit us like a meteor, or we stumble over them regularly – like that step up to the corner shop that you can’t get the pushchair over – or they seep into us like a continuous rain.

What problems have you faced today? What got your blood boiling this week? Last week? Last month? Or are you still fuming over a frustration from last year, from college, or childhood? If you’ve been harbouring it that long it certainly needs fixing.

Collect the problems you experience. Make a note of them. Observe and jot down what you see, without judging. It doesn’t matter how big or small the problems are, whether they affect one person or 1 million – just find and record them.

Make a list of ten, 50 or even 100 problems. Start now:

Go into the world and see what trips you up in your day.Stay at home and see what’s lurking within your kitchen, bedroom or bathroom.Read, watch TV and videos, scroll through social media, play games – however you interact with the real or virtual world.Think back over the last few days to find more things that didn’t work as they should, the frustrations and annoyances and the plain unexpected broken.Delve into the past to dredge up previous issues.Ask your friends, family or co-workers what’s got them riled. Listen to them – they’ll love having your attention. An extra bonus, all this listening will make you more sympathetic as you realise what other people struggle with. More on this in the next chapter.Gather problems in a notebook or use the notes app on your phone, leave yourself voice memos, or take photos and create an album – whichever way you prefer, record them in some way. Don’t let them vanish into thin air.

Get in the habit of gathering problems, noticing stuff that’s interesting, weird and doesn’t work as it should.

Make it a daily routine. Challenge yourself to record ten problems a day for a week and soon you’ll have a notebook bulging with problems waiting to be solved.

And remember, no coming up with solutions yet. The time for ideas will come.

SEEK PROBLEMS, FIND HAPPINESS

Looking for things that make your blood boil might not seem like the route to nirvana, but trust me, finding problems will make you happy. That’s because it engages our ‘seeking’ system which is fuelled by the pleasure-inducing neurotransmitter dopamine.

Seeking is described as the ‘granddaddy’ of our brain systems by Washington State University neuroscientist Dr Jaak Panksepp, who spent his life researching the neurobiological basis of emotions.

The seeking system is a motivational engine that drives all animals to be interested in the world around them, to go out and explore, and get excited by what they find. Panksepp said: ‘it helps fill the mind with interest and motivates organisms to move their bodies effortlessly in search of the things they need, crave, and desire. In humans, this may be one of the main brain systems that generate and sustain curiosity, even for intellectual pursuits.’8

For humans, this system takes us beyond animalistic physical survival and into the world of ideas. It motivates us to find problems and keeps us engaged as we try to solve them. Bring on the dopamine.

FOLLOW YOUR CURSES AND FORM A CLUB

When I started working from home, the local couriers designated my house the unofficial delivery office. While my neighbours were off at work and college, I would always be available to accept a delivery.

Every time the doorbell rang, I would leap from my chair, run down two flights of stairs from the office, and race to the always-locked front door.

Now where did I leave my door keys? Let the hunt begin, rummaging through recently used bags and patting down my jacket pockets, checking kitchen surfaces and scanning table tops. Finding my keys was a problem.

Now, my common-sense solution of fitting a hook by the door isn’t going to win any innovation awards, but it taught me to stop swearing at couriers and instead come up with solutions. That small problem created a habit of noticing, and turned my profanities into opportunities for creativity. I’m not the only one to lean into cursing.

Like many of the best ideas, it started down the pub. Three friends met in the Pipe & Slippers in Bristol to complain about their jobs over a pint or two. As is so often the way, they shared dreams of having an idea that would make them millions. If others could do it, why not them? Between them they had lots of brilliant experience and complementary skills. They should do it.

Unlike many plans dreamt up over a pint or two (or three or four), they made theirs happen. The next month Jeremy Greaves, Mark Dale and Will Bolt booked a meeting room and sat down to pitch ideas to each other. It was fun, but something was missing – they realised that the best ideas don’t happen in a vacuum. Greave explains:

‘We were looking at it the wrong way. We realised that the way you need to start is to think about all the times in your life where you go, “Oh, for fuck’s sake, that doesn’t work” or, “This is no good” or, “I wish there was a product that helped me do this” or, “I wish there was something that stopped this thing happening in my life.”’

The FFS Club was born.

The friends found their mission – whenever they came across a ‘for fuck’s sake’ situation, that’s where true innovation would be found. They thought about all the problems they had in their lives, from annoying software to tripping over on the pavement to not being able to clean a toilet properly.

‘We’re going to find a solution to a problem that exists, where a solution isn’t there yet,’ says Greaves. ‘Once we went and looked at it like that, it really helped us come up with some really good ideas.’

The club now meets once a month for two to three hours. Rather than rely on their own experience, they invite guests who share their FFS moments and provide diverse problems to evaluate. They meet in one of their workplaces and use a room with all the works – whiteboard, computers, a projector. They have a process for evaluating the problems and taking them forward to market – this is important as it forces them to assess viability of ideas at an early stage and reject ones that won’t work. (More on this to come.) After a session they keep true to their roots and head back to the pub for a pint.

As Greave says, the FFS Club ‘is honest, it’s fun, it’s not scary, there’s no bullshit’. And most importantly, it’s working. With several ideas in development the friends pool their shared experience and expertise, work with others, and take forward solutions to problems that didn’t previously exist.

PICK PROBLEMS THAT MATTER – TO YOU

In the early 2000s Anurag Acharya was working for Google. He was part of a small team building the web search index. The company was growing fast and the work was intense. ‘I was burnt out,’ says Acharya. ‘So, I took a break, a sabbatical of sorts.’ Along with his colleague Alex Verstak, the pair started work on a side project. Together they invented Google Scholar, a search engine that indexes scholarly and legal information, enabling anyone, anywhere in the world, to find academic articles.

It solved a problem Acharya had encountered many years ago. Studying in pre-internet days, Acharya had limited access to scholarly articles – if he wanted to read an article, he had to write a letter requesting a copy of the original article. This tactic worked around half the time, with hard copy reprints being sent to him by post. As a student at India’s Institute of Technology, he was deprived of knowledge because of difficulties distributing the latest research information. This was the problem he was destined to solve.

At Google, he was determined to improve access to scholarly information in web search. The issue had changed; instead of the scarcity he experienced as a student, the new problem was that a search query returned everything when people typed a term into a browser. It was information overload. Acharya explains:

‘The challenge is that for web search you have to guess whether the user wants scholarly results or more layperson results. As a first step to working on this, we said: “What if we didn’t have to solve this problem? What could we do if we knew the user wanted scholarly results?”’

Google gave him the opportunity and resources to figure this out. Acharya and Verstak worked with scholarly publishers to build a new web search and, after a few months, they had a demo.

Acharya says: ‘Google provided all that we needed, and asked for, to build Scholar – machines as well as the time for Alex and me to work on it full-time. Once we had a demo, many of our colleagues used it and gave us feedback.’

One of the colleagues who saw the demo was Google co-founder Larry Page. His reaction was to say: ‘Why is this not live yet?’9

Google Scholar was born. With the support of his employer, Acharya could solve a problem he’d been puzzling over for decades. Acharya advises us to ‘pick problems that matter. Something that, if you were wildly successful, would make a difference.’ That’s exactly what you’ll do now.

CHOOSING THE BEST PROBLEM

Which problem matters most to you? It might be the one you feel most strongly about; it could make you angry, excited or super curious to find out more.

Which problem gives you an itch you want to scratch? There’s no right or wrong answer here.

It’s your idea you’ll be creating. Only you can choose. Don’t force it. Enjoy the time you spend. Trust your instincts and forget what other people might say.

Can’t decide which one is best?

Evaluate each one: score them out of ten, type them into a spreadsheet, write them on Post-it notes and rank them, or let your lucky snail loose and pick the one it stops on.

You’ll know when you find it.

And if there are several contenders, that’s fantastic – you have a pipeline to work on and you can give Elon Musk a run for his money in the serial entrepreneur stakes.

Go for the one that interests you most now. File the others away – they’ll be waiting for you when you’re ready to solve them.

How to choose between problems

Decisions, decisions. It’s easy to get overfaced when you’ve got lots of options. If you can’t decide, follow these tips to get unstuck:

Don’t stress about it. Enjoy the process. Ease the pressure off.Read through your problems.Highlight all the ones that make you feel excited.Cross off the ones which make you feel a bit ‘meh’ – wave goodbye to boring.Identify two or three criteria for judging against, think of your own or pick from: access, ease, motivation, size of problem or size of market, your own knowledge, and the all-important tingle factor – what will fulfil your dreams of a lifestyle or business opportunity.Put the problems in a grid and score against your criteria using a one- to five-star system.Tally up the results and see which scores the highest.Finally, trust your gut. You’ll know if it’s the right one.WRITE A PROBLEM STATEMENT

As Charles Kettering, inventor of the electric refrigerator and air conditioner, said: ‘a problem well-stated is half-solved.’

Now you’ve got your problem, let’s halve your work by writing what innovation experts call a ‘problem statement’. It describes the challenge you aim to solve in an easy to understand sentence.

It might take a few attempts to write one, especially if you’re a perfectionist, or are working with other people as you all need to agree the same problem. Here are some ideas to help you nail it:

Grab a piece of paper or, if you’re working with other people, a sheet of flip chart paper.Write a first attempt in the centre of the page with lots of white space around it. Just get it down – the point is to improve it, not start with a perfect version.Look at the sentence and ask if you understand what each word means. For example, when you say ‘people’ do you mean people of a certain age, gender, location? Be precise.Edit, scribbling out words, trying other ones, until you’ve found a version that works for you.If you’re working in a group, you’ll know you’ve got it right when you all agree. This might take some time!Write out the final sentence in best. High five (optional).A STUDENT OF PROBLEMS HONES HER STATEMENT

Nicole Raby, a third-year undergraduate student of biology with enterprise at Leeds University, was tasked with generating business ideas for her final project. She hunted problems and generated a list of potential candidates, starting with her bugbear of finding petite gym wear, to developing diverse makeup and skincare ranges personalised for skin type, and countering the frustration of comparing beauty products online, before landing on one that got her excited.

When students first go to university, they en-counter a new world of opportunity – things to do, people to meet, places to go. It’s all a bit overwhelming, and the fear of missing out can be crushing, imagining that everyone else is having the time of their life while you struggle to figure out what’s going on. Raby experienced this problem herself, and as each new intake of freshers arrived, she saw it reflected in their eager young faces.

With so much going on, and so little time, how can students figure out where to go to make the most of their university experience?

That sentence outlines the problem in broad terms, but to create a great problem statement takes a little more precision. For example, when Raby talks about students – who exactly? Is it all students, first-years, or just freshers in their first few days? What about the phrase ‘where to go’ – is it in the town or city, or just on campus? And how about ‘make the most of’ – what does that mean? What are the benefits they might feel, the gains they might make when they find somewhere to go?

By asking the five Ws – Who, What, Where, When, Why – and the sixth question, How, you’ll get to the bottom of the problem and be able to define what you mean. To refine Raby’s problem, it becomes: As a fresher I want to find out what events are going on in my university campus so I can go along and meet people, make friends and have new experiences.

GET CURIOUS AND GET MOVING

Let’s go back to Jo Caley, standing in her bedroom holding a ripped pair of jeans. Her anger turned to interest when she discovered the problem of vanity sizing that affects millions of women. A self-proclaimed geek, she went digging for data, and it soon snowballed. Like Caley, you’ll need to stay curious.

Over the next few chapters we’ll follow Caley and other startup founders who discovered problems at school, at work and on holiday. We’ll get advice from experts on how to turn those problems into solutions, generate ideas, and choose the best that you can build and share with the world.

Grab your problem by the hand and get moving – the journey has just begun.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

In short: Starting with a problem is the best way to have an idea.Start now: Write a list of problems, as many as you can possibly find or remember.Go expert: Make a habit of gathering problems, keep a problem notebook, or create a FFS club.Be happy: Being curious is fun – find your weird and enjoy getting out of your comfort zone.Next step: Gain a deeper understanding by finding out who else has your problem.Notes

3 Mintel. ‘Online fashion clicks with brits as market increases 152% over past five years.’ 15 April 2011. http://www.mintel.com/press-centre/fashion/online-fashion-clicks-with-brits-as-market-increases-152-over-past-five-years.

4 Graham, Paul. ‘How to get startup ideas.’ November 2012. http://paulgraham.com/startupideas.html.

5 Kelley, David and Kelley, Tom. Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All. Crown Business, 2015, 22.

6