Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Growing up gay is fraught with constraints and even danger in the small Greek-Bahamian community that feels its traditional culture and religious pieties are under threat. The main characters in Helen Klonaris's poetic, inventive and sometimes transgressive collection of short stories confront this reality as part of their lives. Yet there are also ways in which young women in several of the stories search for roots in that tradition – to find within it, alternatives to the dominant influence of the Orthodox church. These include attempts to make connections between their Caribbean lives and the figures and narratives drawn from Greek mythology. Klonaris focuses closely on family relationships, in particular the compexities of father/daughter relationships – ranging from over-bearing authority, absence and incest. Klonaris's characters are very much part of the wider realities in Bahamian society, including the presence of unregistered immigrants from Haiti, and the interplay between fear, repression, hypocrisy and resistance in the relations between the state, the churches and the LGBT community.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 236

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to the following anthologies and journals for publishing earlier versions of some of these stories: Writing the Walls Down, “Weeds”; Let’s Tell This Story Properly, “Cowboy”; The Haunted Tropics: Caribbean Ghost Stories, “Ghost Children”; Poui, “The Lovers”; The New Guard, “If I Had the Wings”; WomanSpeak, “Addie’s House”; and Mission at Tenth, “Flies”.

HELEN KLONARIS

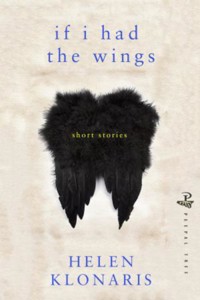

IF I HAD THE WINGS

SHORT STORIES

PEEPAL TREE

First published in Great Britain in 2017

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

© 2017 Helen Klonaris

ISBN13 Print: 9781845233464

ISBN13 Epub: 9781845234058

ISBN13 Mobi: 9781845234065

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may bereproduced or transmitted in any formwithout permission

For my beloved Bahamaland

is that my fathertongue

or mother’s voice?

I cover the violence

under the power

of its own blood

and overwrite a new

life-giving alphabet

building a tower

of tongues teeming

with stories of terror

and ecstasy

— Marion Bethel

THANKS

This book was a long time coming and there are a great many who helped it to grow to completion and fly.

First and foremost I want to thank Peepal Tree Press, and in particular Jeremy Poynting and Hannah Bannister, for all your thoughtful insights, hard work, and expertise.

Thank you also to the many readers of my stories over the past years, and to my mentors Sarah Stone and Carolyn Cooke for your continued support.

Thank you to the Bahamian LGBT community, in particular the Rainbow Alliance of the Bahamas, past and present.

Thank you to my family, especially my parents Mary and James Klonaris, my sisters Tanya Klonaris Azevedo and Tina Klonaris Robinson, and my cousin Maria Govan – for imagining the possible even when I sometimes lost sight.

Thank you to Kathy Bower, Patricia White Buffalo, and Amita.

Thank you to my sister and brother writers for your longtime support and inspiration, particularly Marion Bethel, Patricia Glinton Meicholas, Amir Rabiyah, Lelawatee Manoo Rahming, Ian Strachan, and Lynn Sweeting.

And finally, thank you to my wife Patricia Powell; my love for you is boundless.

CONTENTS

Flies

Cowboy

If I Had the Wings

Ghost Children

Pick Up Girl

Crack in the Wall

Weeds

The Dreamers

FLIES

It was the day before the lowering of the Union Jack and Marjorie St. George was having trouble breathing, even after she had dusted. Her difficulty in drawing a full breath coincided with the whirring of a fly in slow circles across the wide expanse of her living room.

Marjorie St. George did not like flies. But killing them presented a dilemma, because she loved God, and God said thou shalt not kill. Marjorie St. George was meticulous. She loved God meticulously. She kept her heart clean like the rooms of her house. The walls and ceilings shone white, the terrazzo floor gleamed, the silver was polished weekly, and the old Victorian furniture was dusted thrice daily, once following breakfast at six, again after morning rush hour at eleven, and once more after six in the evening, when the rush of cars across the island had slowed and dust off the streets had settled. Her prayers began after the dusting; she could only pray when surfaces were shiny, clean, and the room free from intrusion.

Lord, this is your servant Marjorie. She coughed, cleared her throat and began again. Lord, it is me here. I have been having the dreams again, the ones I told you about last week… She broke off to squint at the black speck hovering next to the cabinet. Her living room had not seen a fly in over twenty years. It took a few moments to realize what the speck was.

She wanted to continue, Lord… it is always the same in the dreams… me one standing on a pristine shore, and in the distance a rumbling, in the distance a great wave… but the whirring sound of the fly grated through her insides, the clean and shiny spaces there, and disturbed them. She shuddered, held a hand to her throat, rubbing her neck anxiously as she followed the fly’s movements, its landing on her white settee, waiting there for her to make a move. She bowed her head, clenched and unclenched her hands, then, I’m sorry, Lord, it seems I have a visitor.

Marjorie prayed on her knees, in front of the television, which was, of course, off. She struggled to her feet, took the fly swat off its perch on top of the TV, and manoeuvred herself close enough to swat the fly in one deft move.

She was eying the fly, holding the fly swat aloft, thinking God did not want her to kill. She thought the fly was staring at her. It looked smug. It had no right whatsoever to her settee, and seemed to be daring her to prove it wrong. She watched it rub its tiny front legs together. Her arm, bent at the elbow, hovered in mid air. If she killed the fly, she would have to ask God for forgiveness. But why should He forgive, knowing she had premeditated not only killing the fly, but asking for His forgiveness? That was cheating. Still, flies were dirty creatures and God must know this. They lived off the dead and dying. They craved the stench of decay, of waste. Perhaps God had not created everything. Perhaps maggots and flies and roaches and rats had given birth to themselves, out of man’s filth. Perhaps all these years God had been testing her.

She had been six years old when she bolted out of the house looking for her cat Delilah. Delilah kept her secrets, remembered everything she could not. But on this day Delilah didn’t come. Marjorie found Delilah under the cherry tree, decapitated by neighbourhood dogs, mauled and left to rot in the sun. Flies swarmed over the carcass. When disturbed by her choked cries, they had flown in a black wave across her pallid face, their tiny pin legs and tongues poking at her lips and cheeks, the insides of her nose, her eyelids, her straight yellow hair. She had screamed and run all the way back to the house, past the lime and dilly trees, past the tool shed and the mango trees, and the wheelbarrow half filled with dirt, to the three steps leading up to the back door, pounding her small fists and weeping for her mother to let her in. It was Rosemary their maid who opened the door for her, Rosemary who sat her next to an open window in the kitchen and told her to breathe till she could catch herself again.

For days she had not been able to get rid of the scent of the rotting cat and the sensation of pin legs and tongues on her lips and eyelids, no matter how many times she washed her face with soap and hot water, dabbed her lips with rubbing alcohol, splashed ammonia on her hair and hands, (as she had seen her mother do after Rosemary kissed her cheek and prophesied she would be unable to carry more children.)

Marjorie became virulently opposed to flies, and anything resembling them. She would not eat Rosemary’s raisin bread or crab and rice, nor her mother’s black currant preserves. At picnics on the beach or at lunch on the patio, she discarded cheese sandwiches flies had hovered over, or, God forbid, rubbed against with their pin legs and tongues.

An only child, Marjorie lived with her parents until their deaths, a month apart. She had been forty-five then, unmarried, and now, at sixty-seven, she lived alone in the same house, caring for it meticulously.

Now here she was, in what had been her parents’ living room, wheezing, fly swat held aloft, her right arm and shoulder aching with indecision. She’d never used the swat before, a long white and turquoise plastic thing she had purchased at the Stop ’n Shop years ago, just in case. Her doors were never left open, and the jalousie windows were screened and kept all but shut. Flies lived in other places, not inside Marjorie’s four walls.

She tried to take a deep breath, but her chest felt constricted. She was dizzy. Her fingers tingled. In that moment it seemed that a light shone brightly inside her (not fiercely like a hurricane flashlight cutting through the dark, but calmly, like a cloudless sunrise, like the ones in pictures with Jesus holding out his hands to say, Come). In the light she saw that God had been waiting for her to see the truth – that flies had come from sin, from man’s nature, not His. Not only was it forgivable to kill them, but necessary.

The fly must have had some prescience. It jumped and flew in a wide arc across the back of the settee to the opposite side, making infinitesimally small lunges at the fabric before settling in on all six of its legs. Marjorie felt confident now of her movements, even though she was breathless. She focused her gaze on the fly. Her hand and arm held high, she moved stealthily towards the opposite shoulder of the settee. She and the fly watched each other. They waited. Marjorie breathed shallowly through her nose, scarcely blinking. The fly rubbed and twitched, but before it could rub its measly legs together once more, she brought the swat down with such force the fly was transformed instantly into a black smudge on the settee – which took her the better part of twenty minutes to scrub clean with Palmolive dish liquid and Blanco bleach. She would have to learn to swat with less force. If she did that, regardless of their natures, she could give them a proper burial in the back yard. Yes, that would be the right thing to do, after all.

Instead of getting better, Marjorie’s breathing troubles worsened. She blamed this on the flies who intruded regularly now. The summer’s unusual humidity had caused her walls to sweat, and dust to stick to them in grimy grey-brown rivulets. Though she herself had not been to the Independence Day’s festivities (why should she, her father’s party had lost, and the country taken over by people he’d said would never be fit to govern), she had heard the heat had been unbearable. Since then, the heat and the flies confirmed that things had taken a turn for the worse. All the more reason to keep a clean house. She spent her mornings listening to “For God So Loved the World” on BBC radio, squatting next to an aluminium bucket of hot soapy water, sponging dirt from the walls and the many framed portraits of her father in his barrister’s robes and wig; her father and other honourable ministers standing outside of the House of Assembly; her father’s parents, Henry and Helen St. George; the premier, soon to be ex-premier, Sir Rupert Sands; and of course the Royal Family. She took particular care shining the glass behind which Prince Charles, on a recent visit to the island, waved and smiled boyishly. Her mother’s side of the family had taken no pictures and so there were none of them on the walls. It was for the best, her mother used to say, let bygones be bygones. As a child, she had misunderstood the word, thinking the spaces between pictures, where the walls were white and absent of memories, were the bygones her mother referred to. As she scrubbed away now at the rivulets streaking these in-between parts of the wall, she permitted herself a brief moment of curiosity about her mother’s people, and why she had never learned their names or set eyes on their faces. Her curiosity quickly turned to frustration and then a strangely familiar despair. She scrubbed harder till even the white paint began to disappear, leaving the wall soft and grey like disembodied thoughts emerging from a forgotten time.

Later, when the walls broke out in fresh sweats, and the afternoon dust settled in thin layers across all her surfaces, Marjorie, urgent and restless, began her ritual cleansings afresh. In the dirt outside, small mounds were evidence of her suffering and her diligence. But still, her breathing was shallow, and her chest hurt when she inhaled.

Her only respite came at night, when she could lie propped against her pillows, staring up at the ceiling and considering which cupboards in the kitchen needed airing, in which corners of closets she had seen a build-up of soft grey fuzz and which necessities she would buy the next day from the Stop ’n Shop.

Perhaps because she paid such close attention to the house, she noticed other things: the slow evaporation of moisture from her skin into the night’s heat. How as she lay there, staring at the ceiling, she could feel her skin stretch and thin, so that when she brought a hand to her face, (she thought a fly had grazed it), her cheek had the feel of a dried banana leaf. She lay awake listening to her heartbeat slow like her mother’s antique clock, the one that stood in the dining room foyer, a golden collection of star-shaped wheels and gears, underneath a clear glass dome, that turned and clicked and chimed on the hour. By the hour she felt the folds around her eyes sink backwards into her head, the whites of her eyes bulge. In the pause between hours, between the turns and clicks of the old clock, she could feel her hair falling out quietly against the flowered pillow case.

In the morning she collected the long silver strands, dropped them into the toilet and flushed. She watched as they swirled and spiralled down the porcelain bowl into the liquid darkness and stench of the septic tank. Then she remembered the bottles of Pine-Sol and Murphy’s Wood Soap, the packets of new yellow felt cloth, and the boxes of mothballs that needed to be bought.

In the days that followed, afraid of suffocating, Marjorie screwed the jalousie windows open and left the front door ajar a few seconds longer than she ordinarily did on her trips into and back from town. Soon, throngs of flies hummed and jackknifed through the lemon-scented air, came to rest on top of the television, the back of the settee, and on days that were particularly still, deliberately brushed against her lips and ear lobes so that she shivered and curled her hands into brittle fists.

She abandoned the washing of the walls to the task of killing flies. There were not enough hours in the day or days in the week to kill them all. Fly swats hung purposefully on door handles, nestled strategically between cushions, rested vigilantly on the toilet tank within easy reach of her groping hand. But for each fly that she swept into a dustpan and dropped into a hole in the ground, ten more surged in as the front door opened and closed. Because she could not keep up with the dust or the flies, and it hurt to breathe, she had abandoned speaking her prayers out loud. The dead flies would speak for her. Mounds littered the backyard like anthills. Like so many deranged breasts.

Her own breasts hung precariously from her exhausted frame. At night she lay unclothed because the chafing of her nightgown against her dry-leaf skin had become unbearable. Staring at the ceiling (away from her wasting breasts that hung off to the sides, so gaunt she thought they might tear off and slither to the floor), she could hear the crawl of wetness down the walls, the careful trickle of dust particles, fanning delta-like across their surface. She could feel, as if it were her own skin, the stretching of limestone and cement and the first appearance of a crack running lengthwise from floor to ceiling in the living room; how this gave permission to others to branch off and multiply across the walls of the house; how the trickle of wet and dust found the slight openings and felt its way into them, reaching for larger spaces. She knew there were puddles of thickened grime collecting in the crease between the wall and floor, in corners where she had not swept or mopped in months. She could smell the stale dust that cloaked the furniture, that clotted the electric outlets, that stopped up the sinks where sour water brooded. But more potent than all these smells was the scent of her body: a bittersweet stink, pungent and foul, like the smell of rotting lilies.

Her mother had loved the scent of lilies. Had grown them each year in time for Easter. Had cut them and placed them in large crystal bowls on the dining-room table and on the dressers in all of the bedrooms. She said they emerged from the dark of the earth just like Jesus emerged white and sweet-smelling from the darkness of death. She could not bear for them to die, since it was death Jesus’ resurrection had conquered, so she plucked them from vases before they could wilt, and pressed them between sheets of grey sugar paper, preserving them, she said, in a suspended state of purity.

It was her stink that made the flies restless and unpredictable. By day they careened into her from surprising angles, throwing themselves at her armpits and wilfully darting into the narrow sloping entrances to her nose. She swatted and snorted till her arms and chest ached with the effort. By night, when the smell was strongest, they circled her bed, whining like mosquitoes, fat as dung beetles, taking turns diving into what was left of her hair, then drifting indolently over her chaffed nipples.

As August Monday dawned, and a faint drumming and cowbelling and horn blowing could be heard rising like joyous heralds from villages across the island, Marjorie awoke to swat at what she thought was a fly crawling across her forehead. She felt with her hands in the darkness, but the air was still and unbothered. A phantom shiver rippled across her skin. She felt hot, feverish on the inside. Then, a sound. She sat forward, listening. Saaah. Saaah. A sound like skin brushing cloth. Like skin brushing skin. It was a sensuous and unfamiliar sound. Swift, smooth and heavy. Brushing then falling. She felt through the darkness for the mattress. At first she thought she was touching paper or leaves, crumpled on the bed. But the familiar curve of a lip, the withered but unmistakable shape of an earlobe, like a bit of dried mango, convinced her that these were pieces of herself: mouth, ears, the cleft of her chin, eyelashes, her nose.

Giddy, she could not tell whether the low drone she heard was coming from outside her head, or from the pieces of herself falling and gathering softly about her on the bed. But as light crept in between shadows, she could see them well. They covered the ceiling and walls, the curtains and door. They glittered and hummed, magnificent swarm.

As if guided by one impulse, the flies rose and converged. She felt them alight on her eyelids and lips, her throat, her shoulder blades and breasts, the hollow bowl of her belly, the desert of her pubis, the dried-out skin of her thighs and shins, her swollen feet; she felt their lightness, the flutter of their wings cooling, the unbearably tender prickle of pin legs and tongues searching, stroking, sinking into her and sucking the remaining wetness, bittersweet, from her skin. She shuddered, sending undulations across the sheen of glittering forms and felt the world coursing through her.

She wanted badly to pray. She moaned and called out, but could not find the place where her voice remained, and worse, could not remember who it was she was calling to. The name she had known had come apart and it was too hard to pull back together. What was a name after all, what was a person or a thing or being? She couldn’t remember, and what she wanted was the smell of things, and the stroking and sinking and sucking; the rubbing, she wanted to feel it inside, or somewhere that was everywhere. She followed the smell of herself and the prickling of feet across her skin till she did not know what was an ear and what was a belly or fingers or toes.

As the flies sucked and rubbed, Marjorie St. George became a quiver of air, a rumour of rotting lilies hovering thickly over the soiled mattress, the numinous undulation of her wanting easing itself into the world like a forbidden word, yes, fanning in thick black waves, yes, out through the wetly dark delta, yes, of cracks in the walls.

COWBOY

The first Saturday Mr. Lebreton came to work in our backyard I was in my room looking at a catalogue picture of the woodcraft construction kit my father said I couldn’t have – because I was a girl. With the kit I could make four miniature wooden houses, and I thought I could sell them to tourists and make a profit. My father said I had a good head for business, but girls didn’t do that kind of work. Still, I wasn’t giving up.

I don’t know what made me notice Mr. Lebreton. He was taller than my father, so tall he had to duck to cross our porch. It is possible that when I first saw him – tall, lanky, brown-skin man – I confused him with wanting what I couldn’t have. I had imagined hammering wooden walls together, pitching the tiny roof, adding a border of picket fencing, and then painting each house in colours I thought tourists would like: turquoise like the sea, yellow like the sun, all the little fences white like every picket fence I had ever seen. I was sure my father would forget I was a girl and be proud of me. I felt that if I couldn’t have that kit, I would never really know myself. Sitting on my bed, biting my thumb, I looked up and saw through my bedroom window Mr. Lebreton crossing the porch, something hesitant and gentle in his stride as he followed my father into the backyard. I had never paid much attention to the garden before, but now I wanted to be in it too. I left the catalogue lying on my bed and went to lean against the white porch bannister.

My father was showing Mr. Lebreton around the garden, gesturing to the weeds, and the patchy grass that was already long and wispy. It looked, my mother said, like people don’t live here. Mr. Lebreton watched my father’s hands and nodded in response. There had been two gardeners before him, but each had left suddenly and never come back. Police raids, my father said; they round them up and send them back to Haiti. A shame. But since my mother believed that having a gardener meant we were coming up in the world, my father was ready to hire another Haitian without papers and hope for the best.

When my father was done showing him around, he said So, your name, how you call yourself? Mr. Lebreton’s voice was raspy and soft and I couldn’t hear his reply, but I heard my father say loudly, Well, from now on, your name is Cowboy, understand? Cow-boy, my father enunciated. Mr. Lebreton nodded, Yes, yes.

My father gave him the name Cowboy (just like he’d chosen new names for the first two gardeners), because it was a name he could pronounce, a name, he would have said, that might grow into something here in this new soil. My father took the name from watching John Wayne movies on American channels every Sunday afternoon. We sat all three of us on the couch in front of the TV, me in between my father and mother, and when the movie got going, my father would repeat John Wayne’s lines, imitating his accent, the calculated drawl of his voice. Later, in the evenings after dinner, when he thought no one could hear or see him, Baba would walk the length of the back porch, his hips thrown forward, his legs turned slightly out, his arms loose and cocked at the same time. Watching from my window, sometimes I saw him pretend to draw a gun from a nonexistent holster and aim it at an invisible foe. When he came back inside, he would clear his throat and ask my mother if it was time for bed. To which she always replied, I don’t know, Van, is it?

Baba named the first two gardeners John and Wayne, and I suppose after a few futile attempts at fishing around for other names, nothing felt so right as Cowboy. After all, he had changed his names from Evangelos to Van, and Papagiorgiou to George, added a new first name, Simon, to the simpler syllables, Van George, making our particular strangeness less apparent to the English-speaking world.

I pretended not to notice Mr. Lebreton, at first, even though his arrival had inspired in me a new level of entrepreneurial yearning. If I could sell enough fruit, like the women selling dillies and carambola and sugar apples down at Potter’s Cay market, then I could make my own money and buy the kit from Maura’s Lumber Yard myself.

I sought out produce from the backyard: there were two mango, one sapodilla, one soursop, one key lime, and two coconut trees that had to be trimmed of their voluminous branches every June when hurricane season began. It was mid-July, and the air was sticky and still. Heat rose up from the red dirt in murky waves. I harvested the fallen coconuts and sold them to passing taxi drivers and their carloads of tourists for a dollar each. When I ran out of coconuts, I gathered dillies: fifty cents for a bag of six. The taxis would stop in front of our house, and the tourists would file out, snapping pictures of the white local and her wares. I was learning how to follow in my father’s footsteps; I was on the road to becoming a good capitalist.

My father had left Greece thirty years ago, at the end of the Second World War, when communists wanted to take over the country. He said the problem with communism was that instead of only some people being poor, it gave everyone the freedom to be poor. At least with capitalism, you stood a chance at making something for yourself. Did he want to turn out like his brother? His brother who lived in a house the size of a bathroom and would never have a way of growing it any bigger? No. Communism makes you weak, he said, tapping his forehead. It makes you lose your passion to put something in the world that was never there before. Sometimes you have to take a chance, and in the new world, a man can take as many chances as he needs.

I took to watching Mr. Lebreton from a corner of the porch. He was the colour of poinciana pods in summer, and had very large, graceful hands. Hands that might have played the piano or written novels, that paused for the briefest moment between tasks, as though some important thing had been forgotten and they were remembering. Hands that, in the aftermath of those brief pauses, stayed busy regardless of what Mr. Lebreton’s eyes might have been envisioning, and it seemed to me they were envisioning tasks I could not see, tasks other than the pruning of lime trees or the weeding of bougainvillea hedges.

I found excuses to get closer when changes in his dress caught my eye.