1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

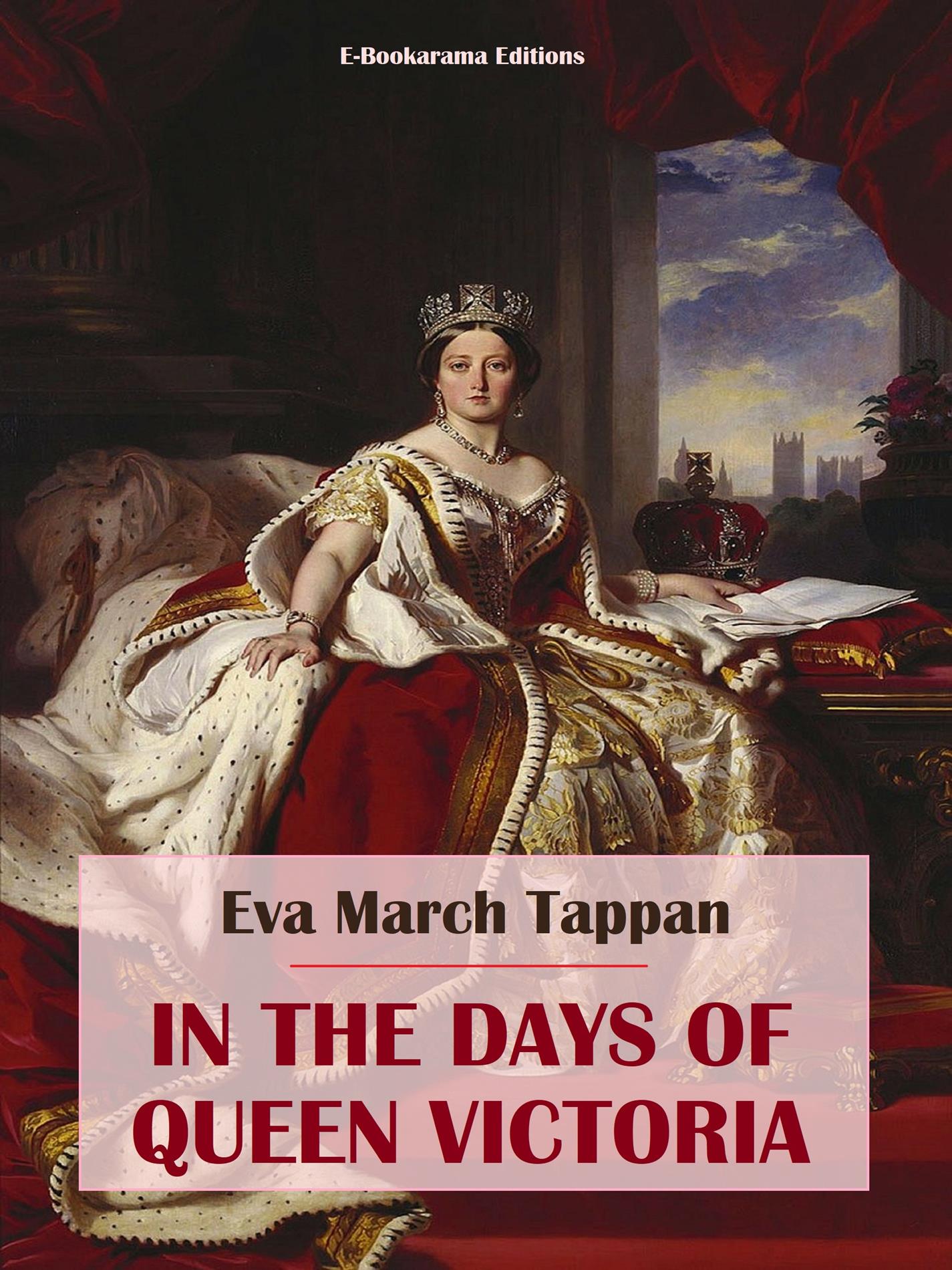

- Herausgeber: Eva March Tappan

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Of all the sovereigns that have worn the crown of England, Queen Elizabeth is the most puzzling, the most fascinating, the most blindly praised, and the most unjustly blamed. To make lists of her faults and virtues is easy. One may say with little fear of contradiction that her intellect was magnificent and her vanity almost incredibly childish; that she was at one time the most outspoken of women, at another the most untruthful; that on one occasion she would manifest a dignity that was truly sovereign, while on another the rudeness of her manners was unworthy of even the age in which she lived. Sometimes she was the strongest of the strong, sometimes the weakest of the weak.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

In the Days of Queen Elizabeth

By

Eva March Tappan

Table of Contents

PREFACE

CHAPTER I. THE BABY PRINCESS

CHAPTER II. THE CHILD ELIZABETH

CHAPTER III. A BOY KING

CHAPTER IV. GIVING AWAY A KINGDOM

CHAPTER V. A PRINCESS IN PRISON

CHAPTER VI. FROM PRISON TO THRONE

CHAPTER VII. A SIXTEENTH CENTURY CORONATION

CHAPTER VIII. A QUEEN’S TROUBLES

CHAPTER IX. ELIZABETH AND PHILIP

CHAPTER X. ENTERTAINING A QUEEN

CHAPTER XI. ELIZABETH’S SUITORS

CHAPTER XII. THE GREAT SEA-CAPTAINS

CHAPTER XIII. THE NEW WORLD

CHAPTER XIV. THE QUEEN OF SCOTS

CHAPTER XV. THE SPANISH ARMADA

CHAPTER XVI. CLOSING YEARS

Elizabeth, Queen of England.

PREFACE

Of all the sovereigns that have worn the crown of England, Queen Elizabeth is the most puzzling, the most fascinating, the most blindly praised, and the most unjustly blamed. To make lists of her faults and virtues is easy. One may say with little fear of contradiction that her intellect was magnificent and her vanity almost incredibly childish; that she was at one time the most outspoken of women, at another the most untruthful; that on one occasion she would manifest a dignity that was truly sovereign, while on another the rudeness of her manners was unworthy of even the age in which she lived. Sometimes she was the strongest of the strong, sometimes the weakest of the weak.

At a distance of three hundred years it is not easy to balance these claims to censure and to admiration, but at least no one should forget that the little white hand of which she was so vain guided the ship of state with most consummate skill in its perilous passage through the troubled waters of the latter half of the sixteenth century.

Eva March Tappan.

Worcester, March, 1902.

CHAPTER I.THE BABY PRINCESS

Two ladies of the train of the Princess Elizabeth were talking softly together in an upper room of Hunsdon House.

“Never has such a thing happened in England before,” said the first.

“True,” whispered the second, “and to think of a swordsman being sent for across the water to Calais! That never happened before.”

“Surely no good can come to the land when the head of her who has worn the English crown rolls in the dust at the stroke of a French executioner,” murmured the first lady, looking half fearfully over her shoulder.

“But if a queen is false to the king, if she plots against the peace of the throne, even against the king’s very life, why should she not meet the same punishment that the wife of a tradesman would suffer if she strove to bring death to her husband? The court declared that Queen Anne was guilty.”

“Yes, the court, the court,” retorted the first, “and what a court! If King Henry should say, ‘Cranmer, cut off your father’s head,’ and ‘Cromwell, cut off your mother’s head,’ they would bow humbly before him and answer, ‘Yes, sire,’ provided only that they could have wealth in one hand and power in the other. A court, yes!”

“Oh, well, I’m to be in the train of the Princess Elizabeth, and I’m not the one to sit on the judges’ bench and say whether the death that her mother died yesterday was just or unjust,” said the second lady with a little yawn. “But bend your head a bit nearer,” she went on, “and I’ll tell you what the lord mayor of London whispered to a kinsman of my own. He said there was neither word nor sign of proof against her that was the queen, and that he who had but one eye could have seen that King Henry wished to get rid of her. But isn’t that your brother coming up the way?”

“Yes, it is Ralph. He is much in the king’s favor of late because he can play the lute so well and can troll a poem better than any other man about the court. He will tell us of the day in London.”

Ralph had already dismounted when his sister came to the hall, too eager to welcome him to wait for any formal announcement of his arrival.

“Greeting, sister Clarice,” said he as he kissed her cheek lightly. “How peaceful it all is on this quiet hill with trees and flowers about, and breezes that bring the echoes of bird-notes rather than the noise and tumult of the city.”

“But I am sure that I heard one sound of the city yesterday, Ralph. It was the firing of a cannon just at twelve. Was not that the hour when the stroke of the French ruffian beheaded the queen? Were there no murderers in England that one must needs be sent for across the water?”

“I had hardly thought you could hear the sound so far,” said her brother, “but it was as you say. The cannon was the signal that the deed was done.”

“And where was King Henry? Was he within the Tower? Did he look on to make sure that the swordsman had done his work?”

“Not he. No fear has King Henry that his servants will not obey him. He was in Epping Forest on a hunt. I never saw him more full of jest, and the higher the sun rose, the merrier he became. We went out early in the morning, and the king bade us stop under an oak tree to picnic. The wine was poured out, and we stood with our cups raised to drink his health. It was an uproarious time, for while the foes of the Boleyns rejoiced, their friends dared not be otherwise than wildly merry, lest the wrath of the king be visited upon them. He has the eye of an eagle to pierce the heart of him who thinks the royal way is not the way of right.”

“The wine would have choked me,” said Clarice, “but go on, Ralph. What next?”

“One of the party slipped on the root of the oak, and his glass fell on a rock at his feet. The jesting stopped for an instant, and just at that moment came the boom of a cannon from the Tower. King Henry had forbidden the hour of the execution to be told, but every one guessed that the cannon was the signal that the head of Queen Anne had been struck off by the foreign swordsman. The king turned white and then red. I was nearest him, and I saw him tremble. I followed his eye, and he looked over the shoulder of the master of the hunt far away to the eastward. There was London, and up the spire of St. Paul’s a flag was slowly rising. It looked very small from that distance, but it was another signal that the stroke of the executioner had been a true one.”

“It is an awful thing to take the life of one who has worn the crown,” murmured Clarice. “Did the king speak?”

“He half opened his lips and again closed them. Then he gave a laugh that made me shiver, and he said, ‘One would think that the royal pantry could afford no extra glass. That business is finished. Unloose the dogs, and let us follow the boar.’ Greeting, Lady Margaret,” said Ralph to a lady who just then entered the room. He bowed before her with deep respect, and said in a low, earnest tone:—

“May you find comfort and courage in every trouble that comes to you.”

Lady Margaret’s eyes filled with tears as she said:—

“I thank you. Trouble has, indeed, come to me in these last few years. Where was the king yesterday—at the hour of noon, I mean? Had he the heart to stay in London?”

“He had the heart to go on a hunt, but it was a short one, and almost as soon as the cannon was fired, he set off on the hardest gallop that ever took man over the road from Epping Forest to Wiltshire.”

“To the home of Sir John Seymour?”

“The same. Know you not that this morning before the bells rang for noon Jane Seymour had taken the place of Anne Boleyn and become the wife of King Henry?”

“No, I knew it not,” answered Lady Margaret, “but what matters a day sooner or later when a man goes from the murder of one wife to the wedding of another?”

“True,” said Ralph. Clarice was sobbing softly, and Lady Margaret went on, half to Ralph and half to herself:—

“It was just two years ago yesterday when Lady Anne set out for London to be crowned. I never saw the Thames so brilliant. Every boat was decked with flags and streamers, edged with tiny bells that swung and tinkled in the breeze. The boats were so close together that it was hard to clear a way for the lord mayor’s barge. All the greatest men of London were with him. They wore scarlet gowns and heavy golden chains. On one side of the lord mayor was a boat full of young men who had sworn to defend Queen Anne to the death. Just ahead was a barge loaded with cannon, and their mouths pointed in every direction that the wind blows. There was a great dragon, too, so cunningly devised that it would twist and turn one way and then another, and wherever it turned, it spit red fire and green and blue into the river. There was another boat full of the fairest maidens in London town, and they all sang songs in praise of the Queen.”

“They say that Queen Anne, too, could make songs,” said Ralph, “and that she made one in prison that begins:—

“Oh, Death, rock me asleep. Bring on my quiet rest.”

“When Anne Boleyn went to France with the sister of King Henry, she was a merry, innocent child. At his door lies the sin of whatever of wrong she has done,” said Lady Margaret solemnly, half turning away from Clarice and her brother and looking absently out of the open window. The lawn lay before her, fresh and green. Here and there were daisies, gleaming in the May sunshine. “I know the very place,” said she with a shudder. “It is the green within the Tower. The grass is fresh and bright there, too, but the daisies will be red to-day with the blood of our own crowned queen. It is terrible to think of the daisies.”

“Pretty daisies,” said a clear, childish voice under the window.

“Let us go out on the lawn,” said Clarice, “it stifles me here.”

“Remember,” bade Lady Margaret hastily, “to say ‘Lady,’ not ‘Princess.’”

The young man fell upon one knee before a tiny maiden, not yet three years old. The child gravely extended her hand for him to kiss. He kissed it and said:—

“Good morrow, my Lady Elizabeth.”

“Princess ’Lizbeth,” corrected the mite.

“No,” said Lady Margaret, “not ‘Princess’ but ‘Lady.’”

“Princess ’Lizbeth,” insisted the child with a stamp of her baby foot on the soft turf and a positive little shake of her red gold curls. “Princess brought you some daisies,” and with a winning smile she held out the handful of flowers to Lady Margaret and put up her face to be kissed.

“I’ll give you one,” said the child to the young man, and again she extended her hand to him.

“Princess ’Lizbeth wants to go to hear the birds sing. Take me,” she bade the attendant. She made the quaintest little courtesy that can be imagined, and left the three standing under the great beech tree.

“That is our Lady Elizabeth,” said Lady Margaret, “the most wilful, winsome little lassie in all the world.”

“But why may she not be called ‘Princess’ as has been the custom?” asked Ralph.

“It is but three days, indeed, since the king’s order was given,” answered Lady Margaret. “When Archbishop Cranmer decided that Anne Boleyn was not the lawful wife of Henry, the king declared that Princess Elizabeth should no longer be the heir to the throne, and so should be called ‘Lady’ instead of ‘Princess.’ It is many months since he has done aught for her save to provide for her safe keeping here at Hunsdon. The child lacks many things that every child of quality should have, let alone that she be the daughter of a king. I dare not tell the king her needs, lest he be angry, and both the little one and myself feel his wrath.”

The little daughter of the king seems to have been entirely neglected, and at last Lady Margaret ventured to write, not to the king, but to Chancellor Cromwell, to lay before him her difficulties. Here is part of herletter:—

“Now it is so, my Lady Elizabeth is put from that degree she was afore, and what degree she is at now, I know not but by hearsay. Therefore I know not how to order her myself, nor none of hers that I have the rule of, that is, her women and grooms, beseeching you to be good Lord to my good Lady and to all hers, and that she may have some raiment.” The letter goes on to say that she has neither gown, nor slip, nor petticoat, nor kerchiefs, nor neckerchiefs, nor nightcaps, “nor no manner of linen,” and ends, “All these her Grace must have. I have driven off as long as I can, that by my troth I can drive it off no longer. Beseeching ye, mine own good Lord, that ye will see that her Grace may have that which is needful for her, as my trust is that ye will do.”

The little princess had a good friend in Lady Margaret Bryan, the “lady mistress” whom Queen Anne had put over her when, as the custom was, the royal baby was taken from her mother to dwell in another house with her own retinue of attendants and ladies in waiting. In this same letter the kind lady mistress ventured to praise the neglected child. She wrote of her:—

“She is as toward a child and as gentle of condition as ever I knew any in my life. I trust the king’s Grace shall have great comfort in her Grace.” Lady Margaret told the chancellor that the little one was having “great pain with her great teeth.” Probably the last thing that King Henry thought of was showing his daughter to the public or making her prominent in any way, but the lady mistress sturdily suggested that if he should wish it, the Lady Elizabeth would be so taught that she would be an honor to the king, but she must not be kept too long before the public, she must have her freedom again in a day or two.

A small difficulty arose in the house itself. The steward of the castle wished the child to dine at the state table instead of at her own more simple board.

“It is only fitting,” said he, “for her to dine at the great table, since she is at the head of the house.”

“Master Steward,” declared Lady Margaret, “at the state table there would be various meats and fruits and wines that would not be for her good. It would be a hard matter for me to keep them from her when she saw them at every meal.”

“Teach her that she may not have all that she sees,” said the steward.

“The table of state is no place for the correcting of children,” retorted Lady Margaret, and she wrote to the chancellor about this matter also. “I know well,” said she, “if she [Elizabeth] be at the table of state, I shall never bring her up to the king’s Grace’s honor nor hers, nor to her health. Wherefore I beseech you, my Lord, that my Lady may have a mess of meat to her own lodging, with a good dish or two that is meet for her Grace to eat of.”

Besides the Lady Elizabeth and her household, the lady mistress, the steward, the ladies of her train, and the servants, there was one other dweller in this royal nursery, and that was the Lady Mary, a half-sister of the little Elizabeth. Mary’s mother had been treated very cruelly and unfairly by King Henry, and had finally been put away from him that he might marry Anne Boleyn.

As a child Mary was shown more honor than had ever been given to an English princess before. The palace provided for her residence was carried on at an enormous expense. She had her own ladies in waiting, her chamberlain, treasurer, and chaplain, as if she were already queen. Even greater than this was her glory when on one occasion her father and mother were absent in France, for she was taken to her father’s palace, and there the royal baby of but three or four years represented all the majesty of the throne. The king’s councilors reported to him that when some gentlemen of note went to pay their respects at the English court, they found this little child in the presence chamber with her guards and attendants, and many noble ladies most handsomely apparelled. The councilors said that she welcomed her guests and entertained them with all propriety, and that finally she condescended to play for them on the virginals, an instrument with keys like those of a piano. If half this story is true, it is no wonder that the delighted courtiers told the king they “greatly marvelled and rejoiced.”

The following Christmas she spent with her father and mother. She had most valuable presents of all sorts of articles made of gold and silver; cups, saltcellars, flagons, and—strangest of all gifts for a little child—a pair of silver snuffers. One part of the Christmas celebration must have pleased her, and that was the acting of several plays by a company of children who had been carefully trained to entertain the little princess.

When Mary was but six years old, it was arranged that she should marry the German emperor, Charles V. He came to England for the betrothal, and remained several weeks. Charles ruled over more territory than any other sovereign of the times, and he was a young man of great talent and ability. The child must be educated to become an empress. Being a princess was no longer all play. A learned Spaniard wrote a profound treatise on the proper method of training the little girl. He would allow her to read the writings of some of the Latin poets and orators and philosophers, and she might read history, but no romances. A Latin grammar was written expressly for her, and she must also study French and music. There seems to have been little thought of her recreation save that it was decreed that she might “use moderate exercise at seasons convenient.”

So it was that the pretty, merry little maiden was trained to become an empress. When she was ten years old, she sent Charles an emerald ring, asking him whether his love was still true to her. He returned a tender message that he would wear the ring for her sake; and yet, the little girl to whom he had been betrothed never became the bride of the emperor.

Charles heard that King Henry meant to put away his wife, and if that was done, it was probable that Mary would no longer be “Princess of Wales,” and would never inherit her father’s kingdom. The emperor was angry, and the little girl in the great, luxurious palace was hurt and grieved.

This was the beginning of the hard life that lay before her. King Henry was determined to be free from his wife that he might make Anne Boleyn his queen. Mary loved her mother with all her heart, but the king refused to allow them to see each other. The mother wrote most tenderly to her child, bidding her be cheerful and obey the king in everything that was not wrong. Mary’s seventeenth birthday came and went. The king had accomplished his wish to put away his wife, and had made Anne Boleyn his queen. One September day their child Elizabeth was born. So far Mary had lived in the greatest state, surrounded by attendants who delighted in showing deference to her wishes, and her only unhappiness had been caused by the separation from her mother and sympathy with her mother’s sufferings. One morning the chamberlain, John Hussey, came to her with downcast eyes.

“Your Grace,” said he, “it is but an hour ago that a message came from his Majesty, the king, and——” His voice trembled, and he could say no more.

“Speak on, my good friend,” said Mary. “I can, indeed, hardly expect words of cheer from the court that is ruled by her who was once my mother’s maid of honor, but tell me to what purport is the message?”

“No choice have I but to speak boldly and far more harshly than is my wish,” replied the chamberlain, “and I crave your pardon for saying what I would so gladly leave unsaid. I would that the king had named some other agent.”

“But what is the message, my good chamberlain? Must I command it to be told to me? My mother’s daughter knows no fear. I am strong to meet whatever is to come.”

“The king commands through his council,” said the chamberlain in a choking voice, “that your Grace shall no longer bear the title of ‘Princess,’ for that belongs henceforth to the child of himself and Queen Anne. He bids that you shall order your servants to address you as ‘Lady Mary,’ and that you shall remove at once to Hunsdon, the palace of the Princess Elizabeth, for she it is who is to be his heir and is to inherit the kingdom.”

“I thank you,” said Mary calmly, “for the courtesy with which you have delivered the message; but I am the daughter of the king, and without his own letter I refuse to believe that he would be minded to diminish the state and rank of his eldest child.”

A few days later there came a letter from an officer of the king’s household bidding her remove to the palace of the child Elizabeth.

“I will not accept the letter as the word of my father,” declared Mary. “It names me as ‘Lady Mary’ and not as ‘Princess’;” and she straightway wrote, not to the council, but directly to the king:—

“I will obey you as I ought, and go wherever you bid me, but I cannot believe that your Grace knew of this letter, since therein I am addressed as ‘Lady Mary.’ To accept this title would be to declare that I am not your eldest child, and this my conscience will not permit.” She signs herself, “your most humble daughter, Mary, Princess.”

King Henry was angry, and when Queen Anne came to him in tears and told him a fortune-teller had predicted that Mary should rule after her father, he declared that he would execute her rather than allow such a thing to happen. Parliament did just what he commanded, and now he bade that an act be passed settling the crown upon the child of Queen Anne. Mary’s luxurious household of more than eightscore attendants was broken up, and she herself was sent to Hunsdon. Many of her attendants accompanied her, but they were bidden to look no longer upon her as their supreme mistress. They were to treat the child Elizabeth as Princess of Wales and heir to the throne of England.

CHAPTER II.THE CHILD ELIZABETH

It was a strange household at Hunsdon, a baby ruler with crowds of attendants to do her honor and obey her slightest whim. Over all was the strong hand of the king, and his imperious will to which every member of the house yielded save the one slender girl who paid no heed to his threats, but stood firmly for her mother’s rights and her own.

For more than two years all honor was shown to the baby Elizabeth, but on the king’s marriage to Jane Seymour, he commanded his obedient Parliament to decree that Elizabeth should never wear the crown, and that, if Jane had no children, the king might will his kingdom to whom he would. To the little child the change in her position was as yet a small matter, but to the young girl of twenty-one years the future seemed very dark. Her mother had died, praying in vain that the king would grant her but one hour with her beloved daughter. Mary was fond of study and spent much of the time with her books. Visitors were rare, for few ventured to brave the wrath of Henry VIII., but one morning it was announced that Lady Kingston awaited her Grace.

“I give you cordial greeting,” said Mary. “You were ever true to me, and in these days it is but seldom that I meet a faithful friend.”

“A message comes to your Grace through me that will, I hope, give you some little comfort,” said Lady Kingston.

“From my father?” cried Mary eagerly.

“No, but from one whose jealous dislike may have done much to turn the king against you, from her who was Anne Boleyn. The day before her death,” continued Lady Kingston, “she whispered to me, ‘I have something to say to you alone.’ She sent away her attendants and bade me follow her into the presence chamber of the Tower. She locked and bolted the door with her own hand. Then she commanded, ‘Sit you down in the royal seat.’ I said, ‘Your Majesty, in your presence it is my duty to stand, not to sit, much less to sit in the seat of the queen.’ She shook her head and said sadly, ‘I am no longer the queen. I am but a poor woman condemned to die to-morrow. I pray you be seated.’ It seemed a strange wish, but she was so earnest that I obeyed. She fell upon her knees at my feet and said, ‘Go you to Mary, my stepdaughter, fall down before her feet as I now fall before yours, and beg her humbly to pardon the wrong that I have done her. This is my message.’”

Mary was silent. Then she said slowly:—

“Save for her, my mother’s life and my own would have been full of happiness, but I forgive her as I hope to be forgiven. The child whom she has left to suffer, it may be, much that I have suffered, shall be to me as a sister—and truly, she is a winsome little maiden.” Mary’s face softened at the thought of the baby Elizabeth.

She kept her word, and it was but a few weeks before Mary, who had once been bidden to look up to the child as her superior, was generously trying to arouse her father’s interest in his forsaken little daughter. Henry VIII., cruel as he showed himself, was always eager to have people think well of him, and in his selfish, tyrannical fashion, he was really fond of his children. Mary had been treated most harshly, but she longed to meet him. Her mother was dead, she was alone. If he would permit her to come to him, it might be that he would show her the same kindness and affection as when she was a child. She wrote him submissive letters, and finally he consented to pardon her for daring to oppose his will. Hardly was she assured of his forgiveness before she wrote:—

“My sister Elizabeth is in good health, thanks to our Lord, and such a child as I doubt not but your Highness shall have cause to rejoice of in time coming.”

The months went by, and when Elizabeth was about four years old, a message came from the king to say that a son was born to him, and that the two princesses were bidden to come to the palace to attend the christening.

Such a celebration as it was! The queen was wrapped in a mantle of crimson velvet edged with ermine. She was laid upon a kind of sofa on which were many cushions of damask with border of gold. Over her was spread a robe of fine scarlet cloth with a lining of ermine. In the procession, the baby son was carried in the arms of a lady of high rank under a canopy borne by four nobles. Then came other nobles, one bearing a great wax candle, some with towels about their necks, and some bringing bowls and cups, all of solid gold, as gifts for the child who was to inherit the throne of England. A long line of servants and attendants followed. The Princess Mary wore a robe of cloth of silver trimmed with pearls. Every motion of hers was watched, for she was to be godmother to the little child. There was another young maiden who won even more attention than the baby prince, and this was the four-year-old Princess Elizabeth. She was dressed in a robe of state with as long a train as any of the ladies of the court. In her hand she carried a golden vase containing the chrism, or anointing oil, and she herself was borne in the arms of the queen’s brother. She had been sound asleep when the time came to make ready for the ceremony, for the christening took place late in the evening, and the procession set out with the light of many torches flashing upon the jewels of the nobles and ladies of rank and upon the golden cups and bowls.