Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

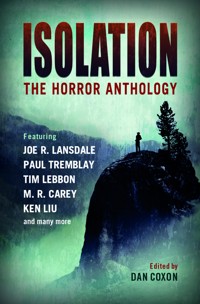

A chilling horror anthology of 18 stories about the terrifying fears of isolation, from the modern masters of horror. Featuring Tim Lebbon, Paul Tremblay, Joe R. Lansdale, M.R. Carey, Ken Liu and many more. Lost in the wilderness, or shunned from society, it remains one of our deepest held fears. This horror anthology calls on leading horror writers to confront the dark moments, the challenges that we must face alone: hikers lost in the woods; astronauts adrift in the silence of deep space; the quiet voice trapped in a crowd; the prisoner, with no hope of escape. Experience the chilling terrors of Isolation. Featuring Paul Tremblay, Joe R. Lansdale, Ken Liu, M.R. Carey, Jonathan Maberry, Tim Lebbon, Lisa Tuttle, Michael Marshall Smith, Ramsey Campbell, Nina Allan, Laird Barron, A.G. Slatter, Mark Morris, Alison Littlewood, Owl Goingback, Brian Evenson, Marian Womack, Gwendolyn Kiste, Lynda E. Rucker and Chikodili Emelumadu.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 629

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Introduction

The Snow Child | Alison Littlewood

Friends for Life | Mark Morris

Solivagant | A. G. Slatter

Lone Gunman | Jonathan Maberry

Second Wind | M. R. Carey

Under Care | Brian Evenson

How We Are | Chịkọdịlị Emelụmadụ

The Long Dead Day | Joe R. Lansdale

Alone is a Long Time | Michael Marshall Smith

Chalk. Sea. Sand. Sky. Stone. | Lynda E. Rucker

Ready or Not | Marian Womack

Letters to a Young Psychopath | Nina Allan

Jaunt | Ken Liu

Full Blood | Owl Goingback

The Blind House | Ramsey Campbell

There’s No Light Between Floors | Paul Tremblay

So Easy to Kill | Laird Barron

The Peculiar Seclusion of Molly McMarshall | Gwendolyn Kiste

Across the Bridge | Tim Lebbon

Fire Above, Fire Below | Lisa Tuttle

Acknowledgements

About the Authors

About the Editor

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

A Universe of Wishes

Cursed

Daggers Drawn

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered, the Missing, the Returned…

Exit Wounds

Hex Life

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Invisible Blood

New Fears

New Fears 2

Out of the Ruins

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre

Rogues

Vampires Never Get Old

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands: The New Apocalypse

When Things Get Dark

Wonderland

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Isolation: The Horror Anthology

Print edition ISBN: 9781803360683

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803360690

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Introduction © Dan Coxon 2022

The Snow Child © Alison Littlewood 2022

Friends for Life © Mark Morris 2022

Solivagant © A. G. Slatter 2022

Lone Gunman © Jonathan Maberry 2017. First published in Nights of The Living Dead (St. Martins Griffin, 2017), edited by Jonathan Maberry and George A. Romero. Reprinted by permission of the author.Second Wind © M. R. Carey 2010. First published in The New Dead (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2010), edited by Christopher Golden. Reprinted by permission of the author.Under Care © Brian Evenson 2022How We Are © Chịkọdịlị Emelụmadụ 2022The Long Dead Day © Joe R. Lansdale 2007. First published in The Shadows, Kith and Kin (Subterranean Press, 2007). Reprinted by permission of the author.Alone is a Long Time © Michael Marshall Smith 2022Chalk. Sea. Sand. Sky. Stone. © Lynda E. Rucker 2022Ready or Not © Marian Womack 2022Letters to a Young Psychopath © Nina Allan 2022Jaunt © Ken Liu 2021. First published in Make Shift: Dispatches from the Post-Pandemic Future (MIT Press, 2021) edited by Gideon Lichfield. Reprinted by permission of the author.Full Blood © Owl Goingback 2022The Blind House © Ramsey Campbell 2022There’s No Light Between Floors © Paul Tremblay 2007. First published in Clarkesworld Issue 8, May 2007. Reprinted by permission of the author.So Easy to Kill © Laird Barron 2022The Peculiar Seclusion of Molly McMarshall © Gwendolyn Kiste 2022Across the Bridge © Tim Lebbon 2022Fire Above, Fire Below © Lisa Tuttle 2022

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

INTRODUCTION

AS I write this, I’m on my eighth day of self-isolation, our entire household having contracted Covid-19. The experience is one you might be familiar with. Over the last two years, as the coronavirus pandemic has spread across the globe, it’s ironic that one of the defining communal experiences has been isolation. Just as I am confined in my home, so are thousands of others across the country, and across the globe—all of us alone in our bubbles, together.

Of course, horror has always been aware of the dangers of isolation. From the Overlook Hotel to the Nostromo, there are perils awaiting us when we drift too far from society’s faint circle of light. We have an inbuilt fear of straying outside our communities, of setting foot in the dark woods—a fear that, many thousands of years ago, might have saved our lives. There is danger in the unknown, and the farther you stray into the wilderness, the less you know. In space, no one can hear you scream.

More than the monsters that lurk on the shadowed fringes of society, though, the real danger comes from within. Humans are social animals, and away from the pack we start to lose our identity, question our reason; eventually, we lose our grip on reality. The Overlook may have ghosts in its halls, but it’s Jack Torrance that they prey upon as he goes slowly mad. As Jonathan Maberry says in his Sam Imura story “Lone Gunman”, reprinted in this anthology: “Alone, though, it’s easier to be weaker, smaller, to be more intimate with the pain, and be owned by it.” Isolation finds the cracks in our psyche, and works its way insidiously inside.

Isolation: The Horror Anthology encompasses all this and more. There are stories of madness and incarceration, and the loneliness that comes from rejection, or illness, or being caught in an abusive relationship. There are apocalypse stories, including new tales of the world’s end from Tim Lebbon and Lisa Tuttle—because what could be more lonely than a planet gone silent? And as you’d expect, there are monsters too, from vampires and zombies to serial killers and mad gods, all of them sniffing weakness in the isolated and the lonely, circling, waiting for the kill.

Inevitably, Covid-19 rears its spiky head more than once. The pandemic has left scars on our collective psyche that will take years to heal, and some of these stories explore that loss, and the solitude we have all felt at times. One of the stories—Ken Liu’s “Jaunt”—is barely a horror story at all, were it not for the shadow of fear and desperation that hangs over it as he imagines what the future might hold in the post-pandemic age.

Three days from now my quarantine period will end, and I’ll be able to step out of my front door once more, into a world that sometimes feels like a pale imitation of the one we used to know. Hopefully I’ll be able to see family and friends again, regulations permitting; I’ll be able to walk the streets of the town I live in, browse the shops, eat in the cafes. As John Donne wrote four hundred years ago, “No man is an island, entire of itself”—we all need community and social interaction if we are to thrive. How else can we keep the darkness at bay?

DAN COXONJanuary 26, 2022

THE SNOW CHILD

Alison Littlewood

THERE’S a family building a snowman outside a little wooden house. A mother, dad, two kids: perfect. They pat down his sides, laughing at the woolly hat on his head, and then they are gone, left behind us. It’s getting dark and I wonder that such young children are still playing outside, then remember it’s only half past two in the afternoon.

This far north the sun is already fading, blue shadows draping the snow. I’m tired, and not just from the journey: a plane from Stockholm to Kiruna, the northernmost airport in Sweden, and then this bus, which is surprisingly full. But then, it doesn’t go any further than Jukkasjärvi, busy with its ice hotel and reindeer centre and holiday lodges, its church and small supermarket, the clusters of wooden houses each painted a different colour. After this, I have to hope she remembers. I have to hope she is there. Beyond this is only the Arctic Circle and the dark and the cold; where my mother lives, there is nothing.

My unease creeps a little deeper into me. I should have come home sooner. I knew it every time we spoke on the phone, hearing the crisp brittle crust to her voice, the coldness beneath. But somehow one year turned into the next and then another, and anyway, it’s nothing she didn’t expect; it never did take long for her disappointment in me to become resignation. Our conversations consist of the same old expected phrases—Howare you? I’m fine. Good. Yes, soon, I hope. Take care of yourself.Goodbye—all oddly formal, but we’ve been that way for so long I can barely remember anything else.

The last time we spoke, though, there was something else, a new edge to her voice, a jumpiness I hadn’t expected. I’d pictured her huddled into a corner in the store, holding the payphone to her ear, fidgeting with the curly wire and glancing over her shoulder as if afraid someone else might hear.

Still, what did I expect? I’d left her out here all alone, with nothing but the snow and the night that closes in too soon. How could anyone live so remotely without it creeping into them—the cold, endless blue dark? I had wanted to wait for the spring, but that phone call had nagged at me, not the words but the way she said them, and so I’d told her I would come.

The bus slows and I wipe mist from the window, catching a glimpse of lights from the shop. It has grey walls, a yellow awning, a couple of snowmobiles parked outside: it’s all just the same. I queue to get off the bus and catch snippets from the radio. Some kind of protest in Mälmo. The need for rent-controlled accommodation in Stockholm. A child missing from a village near Kiruna, presumed lost in the snow. I pull a face at that. She wouldn’t be the first.

My sister, Alma, had been the youngest child, the good child. And she too was lost, wandering off one day into the trees, her coat as red as blood, her skin as white as snow, her hair almost as pale. To complete the fairy story her eyes ought to have been as black as ebony, but my sister’s eyes were blue, like mine.

Snow had quickly covered her tracks. She never did come back, though my mother searched endlessly, leaving me alone in the cabin, young as I was. Sometimes I didn’t eat. Sometimes I didn’t shower for days, and when I asked about it she told me the oil on my skin would help to keep me warm. I never asked about my father; I had never known him. And even when Mother was there, she was not; as if the most important part of her had retreated, hibernating until this coldest of winters should pass.

Of course, it never did pass, despite Mother trying to act as if life was changeless. I know the cabin will be exactly the same. My room will be there, waiting for me. And Alma’s, more deeply frozen still, everything just as it was when my sister was seven years old.

With a start, I realise that the bent-backed woman just emerging from the shop door is my mother. She goes to one of the snowmobiles, starts putting bags into its panniers. There’s no trailer attached, as if she hasn’t thought about my luggage, and I reflect that it’s a good job I only brought my backpack. I’ll have to wear it as we ride.

She turns and sees me, her reaction only a slight widening of her eyes, more lines carving her skin than I remember. I’m here, I mouth to her. I’m home: Tilda, the other sister. The one who never was quite what Mother wanted, who even now doesn’t have a husband, let alone a child, the one thing that might have melted her.

My mother can’t quite hide her disappointment in any of those things, but mainly, I don’t think she has ever forgiven me for growing up.

* * *

It takes forty minutes: glimpses over my mother’s shoulder of narrow white track, misshapen conifers lumpen with snow, shadows beneath them. Constant shaking and juddering from the uneven surface, the roar of the engine. Mother brought a spare balaclava and helmet, and my coat is windproof, though my feet are already freezing in my boots. It’s minus twenty. There is a road out here, somewhere under the snow, but it won’t be passable for weeks yet. I cling to her too-thin shape as Mother wrestles the snowmobile’s handles, preventing it wandering from the path. All this way and all we’ve managed is Hej and a brief hug, her touch so light I’d almost felt I’d imagined it. Now it’s impossible to talk, hard to see through the speckles of snow thickening on my visor. Mother never hesitates. She knows the way, letting the machine slow at just the right moment, though at first, despite the familiar windows, the snow-weighted roof, I don’t recognise it.

The garden is somehow full of trees. No, not trees. I blink, scarcely taking it in, then it floods in on me all at once. I swing myself from the seat, wrestle the padded helmet off my head, pull the balaclava over my hair. Blink at what she has done.

The garden is full of snowmen, but they are more than that. These things are beautiful, obsessively shaped and wrought. They’re not rough-rolled globes of snow but sculpted, refined, detailed. Not snowmen, but snow-children.

All of them are girls. All of them are shorter than me, about seven years old: just right. They are wearing Alma’s clothes. I recognise a fleece covered in the printed teddy bears she used to love. A corduroy skirt she had begged for. I can’t make out my mother’s words as I step towards them; they reach me but distorted, as if I’m hearing underwater. Perhaps my ears are still ringing from the roar of the engine, though I don’t think that’s entirely it.

I stand in front of the nearest snow-child. Her face is not carved from compacted snow but from ice, set atop a snow body. I look at her smooth cheek, her nose, her chin. Her eyes look back at me, the clearest, palest blue.

“Do you see?” Mother’s voice reaches me clearly now. “I knew you would like them, Tilda.” When I turn, her smile is a little too wide.

There are objects, too, scattered around the garden. A ball. A wooden horse. A plastic doll with white-blond hair. Other things. A cuddly toy puppy, drenched and matted. Building blocks. All placed at the feet of children who will never play with them, never bend to pick them up. I stoop and retrieve an old book, a volume of fairy tales I used to love, the pages clumped and frozen, ruined.

“You see?” Mother crunch-steps to my side. This time, when she speaks, her voice is full of triumph. “They’re real, Tilda. You do see, don’t you?”

It is a long time before I can look at her. She stares back at me, unblinking, her expression one of purest joy.

* * *

I don’t talk to Mother about the snow-children, not yet. I’m not sure what to say. I need to watch her first, decide what I should do. At first, she doesn’t mention them either. She stows the snowmobile around the back of the shed then joins me inside. She speaks words of welcome, bustles about the kitchen, bends to the oven. I recognise the scent of her stew and realise I’m starving. She ladles it into bowls and we eat, her at one side of the wooden table, me at the other, stealing glances at one another. She asks me ordinary things. About my flat in Stockholm, out in the suburbs, far from the little streets of the Old Town so beloved of tourists. My job, nothing special, front of house in a fancy hotel. Whether I’ve met anyone interesting. Not for a long time, Mother.

I ask her little in return. It’s difficult. So much here is the same, and I don’t want to speak about what is different. It strikes me again that I should have come in the spring. At least then the snow-children would be gone, the land revealing itself, green emerging from the white. We fall silent and she takes to staring out of the window, just beyond my head. It’s disconcerting, as if she’s almost but not quite seeing me, and I can’t help wondering if she’s thinking of Alma.

Slowly, a tear runs down her cheek.

I sit up straighter. “Mother, what is it?”

She waves my words away. Wipes the tear away. I see it balanced on the crook of her finger, glistening.

“I’m just so afraid, Tilda,” she says.

I can’t answer. I don’t know how.

She says, “I’m afraid they’ll leave me. So afraid my daughters will melt away.”

I picture a snow-child, her face made of ice. Droplets of water running down her cheek as the temperature rises. All of them becoming soft, misshapen, transforming into something else before they vanish.

I still can’t speak so I go to her and wrap my arms around her shoulders. I feel the little rounded bones of her, hard and unbending. Pat the soft warmth of her hand. Then I clear the table, run hot water into a bowl. After the washing up, there’s little to do—there’s no television here, no DVDs or CD player—and we both say that we’re tired. We agree to go to bed, though I have no idea what time it is at all.

The familiarity of my old room is expected, yet comes as a shock. I set down my pack, sit on the woven blanket covering the eiderdown, feel its slightly rough texture under my fingers. I look at the board games stacked in a corner, the ones I couldn’t play after my sister left. The books, tilted this way and that, gaps on the shelf like pulled teeth. Has Mother offered my books, too, to those figures outside? I shudder to think of it; my books, old friends all, sodden and ruined at their feet.

I get ready for bed, donning an extra layer of thermals, two pairs of socks in case I should have to get up in the night. I didn’t bring slippers but I spy my old moccasins, tucked under my desk. I feel nine years old again and I try to remember what it was like not to be alone but one of two. Alma slips away from me, though, as she always did; instead, the memory that comes is of my mother. The way my door would creak open and she would be standing there, like a ghost. The way she’d slip inside and snuggle the eiderdown under my chin, patting it down, moulding its shape to my body. That was how she used to tuck me in, before Alma left. With tenderness, with love, and without a word.

* * *

Sometime deep in the night—or the early morning—I wake from a dream, its shape rapidly dissolving into mist. I was walking between the trees, I remember that, but I don’t know where I was going. All I could see was the forest and only the forest, nothing else.

Now I hear a sound, one that might have followed me out of my slumber. I remain motionless, scarcely breathing. Just as I decide that of course I won’t hear it again, it wasn’t even real, there it is: the soft, high sound of a child crying.

I tell myself that at any moment I will wake again, for real this time, but I don’t because I’m awake already. The sound comes to me once more: a child’s sob, followed by a stream of words I don’t recognise. The voice is muffled, but I think it’s a girl’s. It sounds as if she’s pleading to come inside.

* * *

It is morning, weak white light seeping over everything. It must be late; I’ve slept in. The sounds I heard last night seem distant as any dream and just as unreal as I swing my legs from the bed and into my old moccasins. They still fit perfectly.

I go to the window and open the curtains. I can’t see the garden from here, though I half expect to see a little frozen face peering in, looking back at me. Of course I don’t. There’s only the side of a hill leading nowhere but into the boreal forest that clothes this latitude for miles and miles. I never did know why Mother decided to move here and I often wondered if it happened when my father left, or died, or when whatever happened to him happened, my mother turning her loneliness into something physical.

The clattering of pots and the hiss of a kettle call me towards the kitchen. I put my head around the door, afraid of what I’ll find—They’rereal, Tilda. You do see, don’tyou?—but Mother is setting out bowls of steaming porridge, glasses of lingonberry juice and a pot of coffee. I can’t help smiling at the old smells. I sit and she puts porridge and juice in front of me, no coffee, and I feel as if I’m nine years old once more.

“What would you like to do today?” She sing-songs the words, her voice a shade too bright. She glances at the window, as if she’s already waiting for me to be gone.

I take a deep breath. “I thought maybe we could talk.” I force myself to smile but she turns away, so I almost don’t see her lip twist.

“I’m going to chop some firewood,” she says. “You’ll need it, I suppose.”

I remember what she said about her snow-daughters melting: I’m just so afraid, Tilda. There’s no sign of her worrying over that now. No sign of whatever madness came to meet her in the cold.

She shifts, as if she knows what I’m thinking. “Together, then,” she says. “Let’s go out, shall we?”

And so we do, both of us heaving sections of a fallen tree onto a block for Mother to cut into pieces before I remove the logs and stack them undercover to dry. She swings the axe easily, for all she looks so stringy and thin. But then, she’s strong; she has to be, out here alone, with no one to help her.

I push aside the guilt that rises and look towards the front garden. I can see only one of the snow-children from here. Ripples of transparent hair flow behind her and one foot is almost lifting from the ground, as if she’s about to skip away. Perhaps she is; perhaps she moved during the night. I wonder if she, too, has pale blue eyes—but I suppose she must have, like Alma’s; like mine. Mother’s children, all.

“Mother,” I try to begin, “you don’t really think they’re real, do you?”

She swings the axe and there’s a loud smack as she sets it quivering deep into the block. “Enough,” she says. “We’ll go inside now, Alma.”

I stare at her. Has it been so very long? But surely she could never forget that it was Alma, the perfect daughter, who went missing; the other who was left behind.

She blinks. “Tilda. Come inside.”

I don’t move and she, too, glances at the thing she has made. “You must know the story,” she spits. “Someone returns home. They find that the woman has a child, one she wished for really, really hard.”

Someone, she said. In the story it was a husband who came home, I knew that, but that’s not what she said.

“And she lives with the child, quite happily, a gift, a joy, until the sun comes and she melts.” She strides over to me, grabs my arm, starts pulling me around the side of the cabin. There they are: snow-child after snow-child, gleaming in the light streaming from the pale white hole in the sky. “In spring,” she adds, needlessly, and points. “This is Istapp. This is Snöflinga, and this—”

Icicle. Snowflake. This is what she has named them. “Mother, listen to yourself. Please. You made these things, you can’t really think—”

She moves quickly. I feel the sting of her slap spreading across my cheek.

“You’ll say nothing.” She pushes her face up close to mine. “Nothing, you understand?”

She turns and stomps away from me, her steps squeaking and crunching in the snow. She doesn’t look back, just opens the door, goes in and closes it after her, as if we’d had a normal conversation.

I put my hand to my face. It is already turning numb as the cold creeps into me.

* * *

Inside, Mother is doing ordinary things. Chopping carrots she must have bought at the store, half a world away. Scooping them into her stew-pot.

“Mother—”

“Nothing,” she snaps, as if completing her earlier sentence. She doesn’t look up at me.

“All right,” I say softly. “I won’t say anything, if you don’t want me to.” I’m already wondering what to do. I can stay with her a few days, but what about after that? I could give up my flat and my job, but the thought of being out here, caught up in her pretence…

I think again of the spring. Her delusions must end then, mustn’t they? I’m not sure if I can last that long. I don’t know if I can bear to watch her pain as all her work, her precious children, melt into the ground.

A sniff comes from somewhere behind me and I whirl about. A little girl is standing in the doorway. She is leaning against the jamb, staring up at me as slowly, slowly, a drip runs down her face. She appears to be about seven years old.

My mouth falls open. “What the—”

I feel, rather than see, Mother rush past. She steps in front of me as if to shield the child from the heat of my gaze and stoops to her. “There you are!” she says, half turning to me again. Her whole demeanour has changed. She looks happy. She looks joyful, her delight brimming over. “You see, Tilda. You see?”

I do see, but I don’t understand and I can’t move.

“I made her,” Mother says simply. “She is my daughter. She’s your sister, Tilda.”

This child doesn’t look anything like my sister. She isn’t Alma. She’s staring down at her feet and her features are half hidden but it’s plain to see that her hair isn’t blond. This girl’s hair is black as ebony and she doesn’t smile back at Mother or even look at her. From what I can make out, her expression is pinched, frozen. Her nose is running, another drip poised to run down her face.

I force myself to speak because someone has to say something, but I barely croak the word. “Hej,” I try. “Hej.”

The child jerks her head, but she gives no sign of recognition and I’m not surprised when she doesn’t answer. Mother starts pulling at her shoulders, twisting her away from me, giving her a little push.

“She can’t talk, Tilda,” she says. “Not like us, not words we can understand. Don’t you know anything?”

Yet the child wriggles her shoulders and pulls away from her. She sticks her arm straight out, pointing towards the window, and she does speak; she says a single word. “Mama.”

I stare, but Mother doesn’t. She starts guiding her along the hall, towards my sister’s room. I can hear her voice, the bright tone of her response. “Yes!” she says. “So clever, my dear. That is your mother—you see her white cloak?”

I realise, as Mother closes the door behind them, that she is talking about the snow.

* * *

I am in my room, sitting on the bed, mobile phone on my lap. I’ve been trying to get it to work, though I don’t know why I bothered. Mobiles don’t work out here. Did I think they’d have built a signal tower in the wilderness since I came here last? Still, I turn it as if at any moment it will ring, connecting me to another world. I unlock it with my thumb, open the messaging service. The last one I had was from a friend at work. Big night out when you’re back! We were planning a nice meal in the Old Town, never mind the expense.

That reminds me I’m hungry. Mother has emerged a couple of times from Alma’s room, but mostly she’s been in there. Muffled voices, rustling sounds, the rattling of dice then the sweeping of game pieces onto the floor. At least, that’s what I thought I’d heard. It might be anything in there. A troll. A witch. Even Alma, her little face so serious, her eyes wide and blue and so very pretty.

I push myself up, walk along the hall, stopping to stare at the two-way radio tucked into its alcove. It’s a last-mile service only, meant for emergencies, enough to reach the nearest neighbour at best. I hear a door open and quickly look away, continuing into the kitchen. There, I see what my mother has laid out on the counter: piles of meat, great joints of elk, all of it glistening and frozen.

Mother comes in, her feet shuffling, pace slow. She sits at the table, her back to me.

“Would you like some lunch, Mother?”

She doesn’t answer so I look in the cupboards, rummage through tins, find some soup. I grab a pan from another cupboard, grimace at the dark crust around its rim.

“Mother?”

She doesn’t even twitch. I run the tap, wash the pots before I use them. When did it get so bad? But it was like this before, I remember. I’ve been washing up since I was nine years old; since Alma went away.

I put the soup on to warm, watch as the surface starts puckering.

“We should eat,” I say. “Mother, we’d better feed the child.”

“My daughter,” she snaps, correcting me.

“Yes.” There’s nothing else I can say.

She lets out a long sigh. “Don’t make it too hot, Tilda. It might hurt her.”

“Yes, Mother.”

“Do you think they’re melting, Tilda? I think they’re already melting. Then it will all end. They’ll come back next year, but they won’t be the same, will they?” She twists in her seat and looks at me. “They’re never the same.”

Now I’m not sure it’s just the snow-children she means.

“Oh, for goodness’ sake,” she snaps, “I’ll do it.” She strides towards me, pushes me aside. Starts clattering bowls onto the counter, one, two, three.

When they’re full, I put out a hand and squeeze her wrist. “Let me do it,” I say. “Let me feed my sister.”

Her frown dissipates as she stares into my eyes. After a long moment, she nods.

* * *

When I open the door to Alma’s room, the child is sitting on the bed. Her eyes are bloodshot and sore, her hair greasy, her fringe a little too long. She follows me with dark brown eyes, sniffing as I sit at her feet. I hold out the soup like a gift.

She shuffles closer, the bed shifting and sinking as she moves. I can smell her; clothes that have been too long in a musty cupboard, the oil of her hair. She is real, this girl. Flesh and blood. Did I really need reassuring of that?

I smile, dip the spoon into the soup and hold it out. She takes it, swallows. Takes it, swallows. She’s hungry. She isn’t made of ice and snow—but I knew that, didn’t I?

She hasn’t uttered a word, but one rises to the surface of my mind anyway and I whisper it to her. Mama.

The child lets out a gasp. She grabs my hand, slopping soup over the rim of the bowl as words burst from her. I can’t make sense of them, but I see the hope that’s suddenly in her eyes. She keeps looking at the window, as if at any moment someone might come, but out there it’s already growing dark.

I wish I could ask her to explain where she came from. I wish she could tell me.

She can’t talk, Tilda. Not like us; not words we can understand.

I recognise her voice, though. I’ve heard it before. I heard it during the night, not through a window, as I’d assumed, but through a door. Not pleading to come in, but crying to get out.

I stroke her back, shushing her as best I can, and try to remember what I’d heard on the radio on the way here. A child missing, from a village near Kiruna. Did they say where, exactly? Or where she was from? I can’t remember, but plenty of tourists fly into that tiny airport in the far north of nowhere. Is this one of their children? And was she lost in the snow—or snatched from her family?

I picture my mother lifting the child’s small form onto the snowmobile. Driving away, her arms around her. Loving her, this little daughter she’d found at last, after all these years. And the snow falling, falling, erasing all trace behind them, as if they’d vanished into a story. A happy ending for someone.

When I re-enter the hall, Mother is nowhere to be seen. I pause by the radio, flick the switch. It doesn’t respond; no light appears. It has the feeling about it of something dead and I look under the little shelf, tracing the wire to its end. My mother has cut the cord in two.

* * *

I shoot out a hand and silence my alarm. I set it last night on a low volume, my mobile coming in useful at last. I knew I’d need to be up and out before the light came to wake me. I’m already dressed but I pull on my boots and an extra jumper and then my coat. I’ll fasten it later, outside. I can’t risk the sound of the zip waking her.

I sneak out into an early morning that isn’t as dark as I expected. The sky at its zenith is black, the stars a bright glitter, but low on the horizon a green veil shifts and dances. The northern lights have come to help light my way.

There’s no helping the sound of my boots on the snow but I stay close to the house, where it’s at least been cleared in the recent past and isn’t so deep. I go around to the back of the shed and tug the cover from the snowmobile, revealing its sleek shine, its gathered power. Then I push open the shed doors, ignoring the shadowed shapes of tools and machinery, everything needed to survive out here, and reach for the hook just inside. My fingers meet with nothing.

Of course the key isn’t there. Had I really imagined she’d leave it for me?

I watch the lurid light stroking and slipping over the curves of the snowmobile, turning the snow the colour of sickness. I check the ignition but it’s empty, a small black slot. So simple; so impossible. I stare into it, thinking of all the movies I’ve seen in Stockholm, the hotwired cars. Always so easy to drive away, but I have no idea how to make it start.

* * *

For the next couple of hours I keep to my room, wondering and wondering where she might have hidden a key. It might be anywhere. She could have thrown it into the snow. Perhaps I’ll find it come the spring, as the white retreats from the earth.

Then I hear sounds coming from outside: sharp cracks and spattering, something breaking like glass. I can’t see anything from my window, so I pull on my coat.

In the front garden, the white figures are motionless. Nothing moves, nothing changes, not here, but I realise that something has. One of the snow-children is broken. Her jumper hangs from her, misshapen; one of her arms is missing. Her neck juts upwards, ending in glinting shards like a broken bottle.

Movement draws my gaze. A dark shape is shuffling, bent-backed, from the shed. It is my mother, the crone; the witch. She stoops and picks up something from the ground, clear and shining. It is the snow-child’s head. It must be heavy, judging by her lurching gait as she moves back towards the shed once more.

I notice her axe, abandoned in the garden. Obscene among the toys lying at the children’s feet.

Mother pauses. She cradles the child’s head in her arms as if it were flesh and blood. “I have to save them,” she says, before she goes back into the shed. A metallic sound is followed by the slight suck of a seal giving way.

The freezer. It had been just on the other side of that thin wooden wall, all the time I’d examined the snowmobile. My mother needs her stores after all, everything she might require to survive out here, spring and summer as well as winter.

I’m just so afraid, … I’m afraid they’ll leave me. So afraid my daughters will melt away.

I remember the meat laid out on the kitchen counter. She’s been emptying the freezer, I realise. Making room for them, her children; her daughters.

* * *

Mother doesn’t seem tired from her labour. The snow-children are shattered, the stumps of legs and bodies lying on the ground. Mainly she seems to have taken arms, hands, heads. The things, I suppose, that are most them; the easiest to store.

Now she is making stew. Mounds of thawed meat litter the counter. It looks like an abattoir after the blood has drained away. She sears the flesh. The smell grows thick in the air.

I don’t try to talk. Wherever Mother has gone, I know I can’t reach her. She left a long time ago: she walked into the woods looking for Alma and she never came back again. She left me here alone.

I am not alone now, of course. Occasionally there is a rustle or some other sound from my sister’s room, but the door doesn’t open. It’s as if Alma is in there, sulking at me, after I’d teased her perhaps, or pulled her hair, or dreamed up some game she didn’t like.

I think of the snowmobile. I could try bending a paperclip and put it into the ignition. I could slip alcohol into Mother’s coffee, get her drunk enough to tell me where the key is. But there’s nothing to drink here. I remind myself she never cared for it, doesn’t have that particular vice, and let out a dry splutter of a laugh.

Mother looks up. I freeze, but after a moment she resumes her work. Chop, chop, chop. One, two, three.

Along the hall, a door whispers open.

Mother’s eyes flick to me, then she carries on. Chop, chop, chop; the sound is no different to before, but I know that it is. She’s listening.

A footstep, so light, so quiet. Then another.

Mother slams down the knife and rushes to the door, pulling it open to reveal a little figure in a blood-red coat, her face blanched white as snow, her hair as black as ebony, the fairy tale at last, but she isn’t going into the forest, oh no: because the witch is here, the witch is my mother, and the witch snatches her up and lifts her from the floor. The little girl squeals, squeeeeeeals, as Mother carries her back into Alma’s room, her room now, and bangs the door closed. The sound isn’t quite final, though. There are others: shouting, crying, muffled sounds, and I stare towards them, feeling that I’ve heard them all; I’ve felt them all, so many times, and I start to shake and feel water running down my face.

After what seems like an age, Mother emerges.

“Leaving,” she snaps. “Always, they leave. Always. All my daughters.”

She returns to the counter and picks up her knife. The sounds are brisk and sharp as she resumes her chopping.

It isn’t until I’m quite certain she won’t notice me, when I have turned invisible to her, that I step softly from the house.

* * *

The freezer is there. A monster of grey metal that can swallow an elk whole. I had half expected to see locks and chains, but there are none. Why should there be? No one ever comes here.

I reach out and lift the lid, adjusting my stance to take the weight. It makes the loud sucking sound of a hungry mouth and cold breath spills out. I look down and see lumpen shapes, just as I’d expected. She has been freezing them, her snow-children; saving them, keeping them safe from the coming spring.

There are finely formed fingers, almost transparent, frozen now for as long as she wishes. Locks of hair, curling and twining yet always keeping their shape. Faces look up at me: cheeks, noses, chins. Their eyes are all the same pale blue; sleeping beauties, all.

Yet I know there is more.

Always, they leave. Always.

I move the pieces aside, then start throwing them to the floor, these perfect things she has made. The things to which she has given her love, though it was never asked for, never expected; never earned. All my daughters. Ice shatters and scatters across the rough concrete and I don’t care. I am glad to see them break.

All my daughters, she had said.

And there, beneath them, I find it. There are pieces of child everywhere, their bodies confused and jumbled together, but only one of them is wrapped in plastic.

The freezer is still half full of hands, arms, heads. They are packed around her, keeping her company. I ease them away from her, my fingertips numb, all feeling long since stolen away.

Pale hair, the shade of moonlight, is curled and crushed between plastic and the frozen dome of her skull. Glitter crusts her skin. Her eyes are white now, the colour of snow. I see all the perfect curves and planes of her, so well-remembered, so very pretty, just as she had always been.

Alma. My sister. My mother had found her after all.

* * *

I don’t wait. Only the length of time it takes for my mother to go into the shed once more, and then I act: I thrust the long pole of a snow shovel through both door handles. She knows she’s trapped at once. She doesn’t shout or squeal; nothing so human. She just starts bang, bang, banging on the wood.

I run into the house. I’m wearing my coat. I touch my pocket, feel the shape of my phone; I can use its compass, keep trying for a signal as we go. I have a warm hat and gloves and two pairs of socks inside my boots. I’ll grab her coat, too; she can dress on the way. I yank open her door and put my finger to my lips, the same in any language: Shh.

I point to the window. “Mama,” I say.

Her eyes widen. She shuffles off the bed and holds out her hand towards me.

Then we’re out. We’re in the snow. I glance over my shoulder, as if someone might be watching us leave, but there is no one, only that relentless banging coming from the shed. I pause to pull the coat over the child’s arms, slip gloves over her hands. Her fingertips are already pink with cold. She grasps for my hand and I hold hers tight as we walk towards the trees, wading into deeper snow. The hole where the sun should be is lowering in the sky, but I think there is time. There has to be time. I glance towards the cabin once more, and see our own deeply shadowed footprints trailing after us.

The sound of splintering wood carries clearly through the cold, clean air. Moments later, there is the roar of an engine.

The child looks up at me. Her eyes are wide and round and full of fear. I yank on her hand and we start to run, but it is slow, so slow. The tracks we leave are like those of an injured animal.

We duck under stunted conifers, dislodging snow from their branches, flakes whispering to the ground all around us. It is almost like fresh snowfall, almost like that day. No, not like that; we were playing then. Let’s play hide and seek, Alma. I’ll come and find you. I promise.

But we aren’t playing now and I will not let her go. I won’t send her away from me, all alone, so small, into the forest.

I pull on her hand, faster, as we crest the hill, reaching an open slope on the other side. Does the engine sound more distant now? A snatch of hope whips away from me on the breeze. No. She knows exactly where we are. She always knew I’d have to run south. It’s just that she can’t weave between the trees; she’s going around them.

We start down the slope and I turn and see her, a black metal gleam growing larger, growling as it comes, like a fearsome beast. She’s bearing down on us, close, closer, and I lift the child into my arms. For the briefest moment it feels like I’m holding a shield, then I throw her away from me, off to the side. I know she’ll land safe. The snow is so soft, after all.

The next instant, I am struck. I am flying, flying through the air. I do not know when I land; there is little difference between the snow and the sky. For a moment there is nothing but white, it is all there is, and then the pain begins.

I do not need to see to know that I am broken into pieces.

My eyes, nose, mouth are full of snow. Cold sends a jolt stinging into my teeth and I splutter, feeling ice running down my skin, already melting. Distantly, my legs burn and throb and insist. I blink, trying to peer down at my body. The snow isn’t pure; it isn’t clean. The snow is tainted with me. All around, red crystals bloom, crimson flowers opening their petals.

Mother walks towards me. The crunch of her footsteps is loud, so loud. It hurts inside my head and I want her to stop and thankfully, she does. She looks down and I see myself reflected in her eyes: the disappointment that quickly turns to resignation as she kneels. Behind her, I glimpse another child, another daughter. Just as she was then, always seven years old. Run, I think, but she doesn’t.

Mother leans over me. Her skin is flecked with ice, but she doesn’t seem to feel it. She bends over as if inspecting me, but I feel something, pat pat pat, and realise that she isn’t. She’s pulling at the snow, mounding it around my body, moulding it to my shape. She means to keep me warm, and I feel the cold leaching from me, quickly fading away. That’s what a mother is, I think, and allow myself to sink deep into the soft pillows. She is covering the blood. She’s making me clean again. Making everything white and perfect; her lovely little snow-child. She starts heaping it onto me, over me, its weight like thick, heavy blankets. Mother is tucking me in. I tell myself she loves me best after all. And it is warm, so warm, the comfort settling into my flesh, wrapping itself about my bones. I can sense sleep waiting for me, not here yet but close, kind, and softly, I smile.

This is how she always did it, I think. With tenderness, with love, and without a word.

She has left a little hole for my eyes. Somehow I can see them peeping out, palest blue amid so much white. And I can see my mother. She is reaching for the child, holding her hand. She is taking my sister home. She’s taking her to be with all her daughters; Mother is going to make sure that she is safe.

FRIENDS FOR LIFE

Mark Morris

IT was a week after Daniel’s mother’s funeral when the flyer landed on the doormat.

It came with a bunch of other junk—Al’sPizzas! Leather Sofas at Half Price! Sell Your Gold for Cash! Daniel was about to dump it all in the recycling when the flyer fluttered out of the pile in his hand and seesawed to the floor. Irritated, he dropped the rest of the junk into the brown plastic tub and bent down, grunting as his pot belly was compressed between his chest and groin. Picking up the flyer, he glanced at the bold blue lettering on its white background:

Feeling lonely? Isolated? No one to talk to?

Then why not come along to Hargrave Community Hall and make some FRIENDS FOR LIFE?

Meetings held every Tuesday evening at 7 p.m. Hope to see you there!

Daniel’s first reaction was a bilious surge of resentment. He didn’t like the suggestion that years of crippling social anxiety could be eradicated simply by meeting up with other, similarly afflicted individuals.

And yet, just for a moment, before the realist in him—all bitterness and anger, brutalised by decades of being bullied, shunned and belittled—crumpled the flyer in his fist and thrust it deep into the recycling tub, a tiny, still-optimistic part of him thought: But whatif…

Daniel was thirty-six. He was five feet five inches tall, and weighed a little over two hundred pounds. His shortness and squatness he had inherited from his parents, who had been so similar in stature that Daniel had often wondered whether it was this that had drawn them together. It was certainly this that had led to Adam Smedley dubbing his family “the Trolls”, and afflicting Daniel with the nickname “Gimli”. It hadn’t helped Daniel’s cause when he had pointed out that Gimli was a dwarf, not a troll. In fact, it had led to Smedley hooting, “Shut up, you geek!” and smacking Daniel so hard in the mouth that he had needed two stitches in his upper lip.

Even when Daniel’s dad dropped dead of a heart attack two years later, while queueing at the deli counter in Sainsbury’s, it hadn’t stopped the bullying and name-calling. Daniel had endured Smedley’s taunts and beatings until the bigger boy had eventually left school at sixteen and joined the police. Daniel himself had stayed on for his A-levels, and then got a job in the IT department of local firm Shaw’s Finance.

Years of humiliation at the hands of Smedley and his cronies—which the rest of the class had found funny and entertaining rather than cruel and demeaning—had crushed his spirit and his confidence. Daniel had now been at Shaw’s for eighteen years, exactly half his life, and in all that time he had never socialised with his workmates, never even attended the firm’s Christmas party or summer BBQ. He had always used his mother as an excuse for why he had to get home—though now that she was dead, of course, he couldn’t do that anymore.

Then again, with everything that had happened in the past two years, he no longer had to. Since the start of the pandemic, Daniel had been working from home, a situation that now looked set to continue indefinitely. At some point during the lockdown, it had occurred to Lionel Shaw that he simply didn’t need to pay for quite so much office space to run his business. All that most of his employees required to do their jobs was a computer and a Zoom link.

And so Daniel, who had previously left the house he shared with his morbidly obese mother to go to work every weekday, suddenly found himself almost as housebound as she was. And at first, despite his mother’s increasing demands, it had been a relief not to interact with other people. Other people made him feel ugly and awkward, not to mention stupid and inarticulate, even though he wasn’t.

After a while, though, the novelty had begun to wear off, and it hadn’t only been down to his mother’s failing health. What was that old saying? Be careful what you wish for. Before the pandemic, Daniel had regarded his bedroom, with its games console and its floor-to-ceiling shelves crammed with books and DVD box sets, as his sanctuary. But when a sanctuary became somewhere you were forced to spend all your time, it started to become less like a sanctuary and more like a prison cell.

“Dani-elll… Dani-elll…” As time wore on, his mother’s voice, which had grown increasingly reedy and more frightened as she neared her end, had become like a hot wire applied to his nerve endings, particularly as her demands had become not just frequent but continuous. Now that her voice had been silenced for ever, though, Daniel missed it desperately. Several times since her death he had woken in the night, certain he could hear her calling. And although his instinctive response as he had thrown back his duvet had been irritable resentment, the instant he remembered she was dead he had felt such a crushing weight of grief that he had collapsed back onto his bed, barely able to move.

Years ago, Daniel had read that grief and depression was like carrying a rucksack full of rocks on your back. Although he felt he’d been carrying such a rucksack for the past twenty-five years, so many more rocks had been added to his burden since his mother’s death that now even simple things, like getting dressed or making a cup of tea, felt like an exhausting trudge up a steep hill. Today was Saturday, and it was in such a state, struggling through the fug of his grief, that he eventually set out that morning to pick up a few provisions. He was passing the chemist’s on the High Street (no longer would he have to queue in there for his mother’s many prescriptions) when a flash of blue letters on white caught his eye.

It was the same flyer he had received that morning. Certain words jumped out at him: lonely… isolated… FRIENDSFOR LIFE! He scowled and trudged on. But there was an identical flyer in the window of the butcher’s shop, and another in the window of the barber’s. And when he reached the little Sainsbury’s over the bridge, there was one on the community noticeboard, its blue lettering jumping out amid the other notices about lost cats and music tuition.

When he got home, wheezing and sweating, he fished the crumpled flyer out of the recycling bin, smoothed it out and read it again.

Hargrave Community Hall… Tuesday evening at7 p.m.…

The Community Hall was only a couple of streets away, three minutes’ walk at most. He had passed it on his way back from Sainsbury’s.

Not that he’d go, of course. He couldn’t face company right now. But maybe at some point in the future…

Though, more than likely, maybe not.

* * *

Perhaps it was fate, perhaps it was a subconscious impulse, but at 7 p.m. the following Tuesday, Daniel was trudging back from Sainsbury’s with a few essentials he’d run out of since the weekend—bread, milk, cereal—when he noticed that the door to the Community Hall was ajar, and light was spilling out of it.

It was a bitterly cold night. September had given way to October, and as the days grew shorter, autumn was enshrouding the land in mist and fallen leaves. Daniel’s breath fogged the air, and the fingers of his gloveless hands ached with cold. As he came parallel with the open door, he heard the comforting clink of crockery, and a brief ripple of laughter. He stopped, his breath rasping in his chest. Through the drifting fog of his own breath, he looked at the bar of welcoming light. He had been in the Community Hall several times with his mother, back in the days when she was still mobile. She’d been a great one for musicals, and had dragged Daniel along to local theatre productions of Annie Get Your Gun and My Fair Lady. Trawling those memories, he pictured what lay beyond that invitingly open door.

There was a short hallway, or vestibule area, with a door leading into a kitchen on the left, and male and female toilets side by side on the right. Straight ahead, at the end of the short hallway, another door led into the hall itself: a large, square, wooden-floored room with high ceilings and a stage at the far end, flanked by velvet curtains. When Daniel had last been here, the hall had been full of chairs, the majority of which were occupied, and he remembered how excited his mother had been, her eyes sparkling, her plump cheeks ruddy. The memory evoked a pang of grief, and was almost enough to make him turn from the welcoming band of light and resume his homeward trek. But before he could, a voice behind him, shy and hesitant, said, “Are you thinking of going in?”

The clench of sadness in Daniel’s gut changed to alarm. He turned to see a woman, perhaps twenty years his senior. She was small, hollow-cheeked, frail as a bird. Dark hair flecked with grey peeked from beneath a woolly hat.

“Er…” Tongue-tied, Daniel stammered, “I’m not… I don’t know.”

“Why don’t you try it? Everyone’s very nice.” The woman’s voice was hesitant, diffident.

Daniel felt himself drawing in beneath his shell. “I don’t think it’s for me.”

“You won’t know unless you try it. My name’s Angela. What’s yours?”

“Er… Daniel.”

“Do you live locally, Daniel?”

Vaguely he waved the hand that wasn’t clutching his bag of groceries. “Couple of streets away.”

“Why not pop in for a cuppa then? There’s no obligation to stay for the duration. And at least it’d warm you up for the rest of your walk home.”

Much to his own surprise, Daniel found himself nodding and following Angela through the doors of the Community Hall.