20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

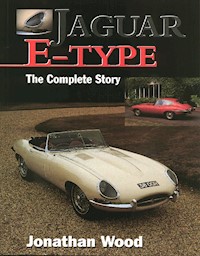

The Jaguar E-type was the outstanding British sports car of the post-war years. Introduced in 1961 it was Jaguar's most numerically successful sports car until production ceased in 1974. Contents include: complete history of the E-type in all its forms; special feature panels throughout; information on buying and maintaining an E-type and full specifications and road tests. Illustrated with specially commissioned colour and black & white photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

JAGUAR E-TYPE

The Complete Story

Jonathan Wood

First published in 1990 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2011

© The Crowood Press Ltd 1990

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 360 3

The photographs in this book were kindly supplied by The Motoring Picture Library, Beaulieu.

The line drawings on pages 25, 30, 62, 63, 70, 83, 102, 103, 136, 137, 145, 174, and 175 were drawn by Nino Acanfora; the photographs on pages 10, 13, 47, 111, 122, 129, 135, 149 and 150 are reproduced courtesy of Jaguar Cars and those on pages 176, 177, 179, 180 and 181 are reproduced courtesy of Paul Skilleter.

Contents

Acknowledgements

The Jaguar E-type in Context

1 The Right Company

2 Jubilation in Geneva

3 Refinement: from 3.8 to 4.2 Litres

4 E-types on the Race Track

5 Fast but not Furious: the Series III E-type

6 Whatever Happened to the F-type?

7 Buying the Right E-type

8 Spare Parts, Clubs and Specialists

Bibliography

Index

Early E-type: a 1961 3.8-litre roadster, fitted with the optional hard-top that subsequently became available, from May 1962, and endured throughout the production life of the Series I and II cars.

Acknowledgements

The majority of the original black and white photographs in this Crowood AutoClassic comes from the National Motor Museum’s Beaulièu photographic library and I am also grateful to Jaguar Cars and Paul Skilleter for providing additional pictures.

My thanks are due to Bob Murray, editor of Autocar & Motor, for his permission to reproduce E-type road tests from past issues of Autocar and Motor magazines. I am also grateful for the assistance provided by Arnold Bolton of Jaguar Cars.

Also the clubs, namely Rosemary Hinton (Jaguar Drivers’ Club) Gordon Wright (Jaguar Enthusiasts’ Club) and John Bridcutt (Jaguar Car Club) kindly provided information about their respective organisations. Thanks are also due to Colin Ford, E-type technical adviser to the Jaguar Enthusiasts’ Club, for advice on some of the practical aspects of E-type ownership.

If you’re a past, present, prospective E-type owner, or just like classic cars, I trust that you’ll be interested in what follows.

Jonathan Wood

THE JAGUAR E-TYPE IN CONTEXT

Prototypes

December 1956Work underway on ‘2.4-litre two-seater’: what will become the E-type15 May 1957Prototype E-type, unofficially designated E1A, tested at the Motor Industry Research Association (MIRA)July 1958Second (Pearl Grey) E-type prototype runningJuly 1959Three E-type prototypes, E1A, Pearl Grey and Cotswold Blue cars, being evaluated27 February 1960E2A sports-racer completedThe E-Type

15 March 1961E-type launched on Press Day at Geneva ShowOctober 19644.2-litre E-type launched at London Motor ShowMarch 19662 + 2 E-type launched11 July 1966Jaguar announces that it will merge with the British Motor Corporation to form British Motor Holdings14 May 1968British Motor Holdings merges with Leyland Motor Corporation to form British Leyland Motor CorporationOctober 1968Series II E-type launched at London Motor ShowJuly 1969William Heynes retires as Jaguar’s chief engineerJuly 1970Malcolm Sayer diesMarch 1971Series III E-type launched3 March 1972Sir William Lyons retires as chairman of Jaguar Cars and becomes its president. He is replaced by F R W ‘Lofty’ England6 October 1973Start of ‘Yom Kippur’ war16 October 1973Gulf States announce seventeen per cent rise in oil prices, so triggering a world recessionJanuary 1974‘Lofty’ England announces his retirement9–13 September 1974The last E-type built during this working week27 November 1974British Leyland meets Department of Industry and banks as it is expected to reach the limit of its £152 million overdraft facility in December18 December 1974Government commissions Ryder ReportFebruary 1975Jaguar announces E-type to cease production1 The Right Company

‘There is nothing more typically English than the Jaguar and Sir William Lyons is the typical Englishman.’

The Motor, 15 March 1961

There are few who would argue that the E-type Jaguar is the most significant British sports car of the post-war years. Derived from the Le Mans winning D-type, it was also the fastest road-going Jaguar of its day and the firm’s most numerically successful two-seater. Not only was the car competitively priced but, above all, the E-type could only have been a Jaguar, such was the sheer beauty and assurance of its unique lines. The E-type was a head turner when it was new. It still is today.

Yet, ironically, this most memorable car was one of the few Jaguars not to have been styled by the company’s shrewd, talented chairman, Sir William Lyons. That accolade must go to the firm’s aerodynamicist, Malcolm Sayer – who also has the D’s lines to his credit – while chief engineer William Heynes was responsible for its sophisticated and unique mechanical structure. When Jaguar introduced its E-type in 1961, it represented the ultimate expression of a line that had begun, back in 1934, when the newly formed S.S. Cars introduced its first sports car.

Sir William Lyons (1901–1985)

Immaculate in a dark suit, Lyons was, by the E-type years, the highest paid executive in British industry, with a salary of £100,000 a year. He also possessed a flair for appointing talented subordinates, whom he persisted in addressing by their surnames. Sir William was enigmatic, cautious, financially canny, and above all, a supreme stylist. Although he drew on continental and American design influences for his cars, he always managed to create the distinctive and stylish ‘Jaguar look’ and this usually ensured a long production run, which kept costs down. When it came to styling exercises, Lyons rarely relied on scale models but opted instead for full size mock-ups. These were often photographed against the background of Wappenbury Hall, near Leamington Spa, where he lived the life of the country gentleman and was proud of his prize-winning herd of Suffolk sheep.

Ironically, Sir William was not responsible for the lines of his most memorable sports car, the E-type. These were the work of aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer. In fact, Lyons was always a little lukewarm about the model. Although it has been suggested that this was because he had not created its memorable lines, the real reason must surely be that SS, and later Jaguar, was essentially a manufacturer of saloon cars, with the low production sports models playing second fiddle to them in terms of volume, and thus profitability. Significantly, the XJ6, a saloon, was his all-time favourite Jaguar.

Lyons always ran a ‘tight ship’, It was an approach perhaps best recalled by an incident that occurred at Browns Lane during a winter when the factory, and its grounds, were covered with a deep fall of snow. ‘Lofty’ England took the opportunity of getting some of Jaguar’s employees to clear snow away from the office block in anticipation of Sir William’s arrival. When Lyons did appear, he told England: ‘That’s very kind of you – well done. But what do the men do normally – how is it that we can spare them?’

THE SWALLOW SIDECAR COMPANY

The S.S. name is rooted in the Swallow Sidecar Company established in 1922 Blackpool, where William Lyons’ father ran a piano sales business. William Lyons teamed up with William Walmsley, who had designed a stylish Zeppelin-shaped motor cycle side-car under the Swallow name. It was decided to expand Walmsley’s business, which had hitherto been confined to his garden shed, and the firm prospered. In 1927, the Swallow Sidecar and Coachbuilding Company diversified by taking an existing car and bodying it with more fashionable coachwork. The first model to benefit from this approach was the popular but utilitarian Austin Seven because, Lyons believed ‘… that it would also appeal to a lot of people if it had a more luxurious and attractive body’. This was a distinctive open tourer, with its own cowled radiator, and was followed in 1928 by a stylish saloon.

The young company had a number of locations during its formative years and Lyons, who had emerged as the dominating personality within the partnership, decided that the business should leave Blackpool and move to the very heart of the motor industry in the city of Coventry. This had been forced on the firm after Lyons had obtained an order from Henlys for 500 Austin Swallows when the factory was only capable of producing two cars a day! He discovered a former Shell filling plant in the Foleshill district of Coventry, at Whitmore Park – later named Swallow Road – and the move was effected between October and November 1928. The firm’s floor space having grown fivefold, Swallow production could be upped from twelve to fifty cars per week. Also, other makes were offered with special coachwork, namely Standard, Swift, Wolseley and Fiat chassis.

Sir William Lyons, creator of the SS and Jaguar marques, poses at Wappenbury Hall with a ‘Series I½’ left-hand drive E-type coupe of the 1967–1968 era. He much preferred the closed version to that of the roadster.

But Lyons was not content with pursuing a secondary, coachbuilding role. He wanted to become a car manufacturer in his own right and the outcome was the S.S.I coupe, which appeared at the very depths of the depression at the 1931 London Motor Show. Its low, very French lines and long bonnet were impressive enough but so was its £310 selling price. The multi-faceted Lyons was a proprietor who individually styled his own products. These usually enjoyed long production runs, so helping to keep the selling price down.

In the first instance however, the S.S.l’s mechanicals did not complement its striking bodywork. The low coupe concealed a special Standard Ensign-derived chassis and was available with 2- or 2.5-litre six-cylinder Standard side-valve engines. In its larger capacity form, the S.S.I could manage 75mph (120kph) on a good day. As for the S.S. name, Lyons was involved in lengthy discussions with Standard, from whom he bought his engines, and later recounted: ‘There was much speculation whether S.S. stood for Standard Swallow or Swallow Special – it was never resolved.’

A much improved S.S.I, with new under-slung chassis, followed for 1933 and, in 1935, came the S.S.90, which was Lyons’ first true sports car. This was an open two-seater with the long stylish wings for which S.S. was soon to be so famous. The S.S.90 was based on a shortened S.S.I chassis, though under the heavily louvred bonnet there was still a Standard side-valve of 2,663cc, but with a high lift camshaft and a 7:1 compression ratio. It was reckoned that the car was capable of speeds approaching 90mph (144kph) which gave the model its name. And like its XK and E-type descendants, it was competitively priced: the S.S.90 sold for £395. In other words you could have bought two S.S.90s for about the price of a top-line 1½-litre Aston Martin. Despite this, only twenty-three examples were sold – discriminating buyers no doubt recognising the limitations of its side-valve power.

No one was more aware of this shortcoming than Lyons himself and he had various thoughts about improving the performance of his cars. The fitment of a Studebaker engine had been contemplated (Henlys had an agency for the make), and a Zoller supercharger was considered. Then Lyons had the good fortune to discover tuning specialist Harry Weslake, who greeted him with the words: ‘Your car reminds me of an overdressed lady with no brains – there’s nothing under the bonnet.’ Weslake began work on an overhead valve conversion for the long suffering 2.6-litre Standard unit. This culminated in an impressive rise from about 75 to 105bhp. But what S.S. required was a proper engineering section and, in April 1935, Lyons appointed thirty-one year old William Heynes from Humber as chief engineer and one man development department!

The pointers to the E-type’s lines can be seen in the Malcolm Sayer-styled C-type, built to win Le Mans, which it did first time out, in 1951. Here Stirling Moss, in XKC053, is pictured at Le Mans in 1953.

Heynes was given the formidable task of getting a new saloon car range ready for the Motor Show six months later. The point must be made at this stage that S.S., and its Jaguar successor, has primarily been a manufacturer of saloon cars, with the more dramatic and memorable sports cars always playing second fiddle to them in numerical, and thus profitable, terms. The new SS Jaguar range duly appeared at the 1935 Show and was also significant for the downgrading of the SS name, which lost its full stops, and the arrival of the Jaguar one. Lyons had asked, what he later described as his ‘publicity department’, in other words his hard-working publicity manager, Bill Rankin, to come up with a list of bird, animal and fish names and Lyons ‘… immediately pounced on Jaguar because it had an exciting sound to me’. He also remembered a friend working on a Siddeley Jaguar aero engine during World War I.

This pivotal year of 1935 also saw the new Weslake converted engine fitted under the bonnet of the SS90 sports car, which gloried in the memorable SS100 name – a reflection of its brake horsepower rather than top speed. Acceleration was a notable improvement on that of the 90 and the car was capable of 90mph (144kph) plus. From 1938 the SS Jaguar saloons were fitted with an enlarged 3.5-litre engine, which was also made available to the SS100, making it a true 100mph (160kph) car. The model was soon making its mark in competition and, in 1937, won the team prize in that year’s RAC Rally. The SS100 remained in production until 1941, by which time 308 examples had been completed.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, Lyons, still only thirty-eight, could look back on a decade of unparalleled growth: SS had just built a record 5,378 cars and, following the 1933 creation of S.S. Cars Ltd, two years later the firm had become a public company. However, William Walmsley had retired in 1934, which left Lyons as undisputed head of the firm. In addition to his outstanding stylistic abilities, Lyons had shown himself to be a shrewd judge of men. Key appointments had included Heynes as chief engineer; Arthur Whittaker, whose association with the firm reached back to its Blackpool roots, as purchasing manager; and in 1938, the engineering team was strengthened by the arrival of the talented Walter Hassan, who had worked for Bentley, ERA and Thomson and Taylor at Brooklands, prior to joining SS as chief experimental engineer.

William Munger Heynes, (1903–1989)

Unquestionably the most influential man in the Jaguar company after Sir William himself, Heynes joined SS as chief engineer in 1935 and became engineering director and vice-chairman in 1961. Initially only assisted by a single draughtsman, Heynes later built up the Jaguar engineering department to be one of the most respected in the industry. In addition, he played a significant role in the creation of the XK engine and his C-type won Le Mans first time out in 1951, laying the foundations for Jaguar’s racing reputation that endures to this day. It was followed by the sports-racing D and, finally, the most memorable of all Jaguar’s sports cars, the E-type.

One of a family of six boys, Leamington Spa-born Heynes attended nearby Warwick Public School and there his science master tried to encourage him to become a surgeon, though the lengthy and necessary training was beyond his family’s resources.

But the medical profession’s loss was the motor industry’s gain. In 1923 he joined Humber as an apprentice, moved to the design office in 1925 and remained with the Coventry company for a further ten years. It says much for Heynes’ abilities that, from 1930 onwards, he was put in charge of the firm’s technical department.

Heynes joined SS Cars in April 1935, and remained with the firm until his retirement in 1969, and while he respected Lyons for his undoubted achievements, he probably knew him better than most, and has left us his observations of the Jaguar chairman, which are both perceptive and candid. On joining SS, he found his young boss, who was only two years his senior, straight talking, lacking a ‘light touch’ and a sense of humour. Lyons also expected those around him to work the same long hours as he did. Some time after Heynes joined SS, he asked Lyons whether he might take a holiday. Lyons responded sharply, ‘Why, are you ill?’ Heynes replied, ‘No but I haven’t had a holiday for two years!’ Heynes became a director in 1946 but thought that the Jaguar board meetings were ‘… a real joke. He [Lyons] just said what he wanted to do and everyone agreed with him – except,’ says Heynes, ‘me’.

THE RIGHT NAME – THE RIGHT MOVES

During hostilities, SS Cars repaired Whitley aircraft fuselages and manufactured them for another bomber, the Stirling, as well as for the Meteor – Britain’s first operational jet. But these years were not solely concerned with such work, as Lyons and his team were planning a new 100mph (160kph) saloon for what they saw as the challenge of the post-war era.

William Heynes, Jaguar’s outstanding chief engineer, who was responsible for the overall conception of the E-type, pictured on the production line with a left-hand drive roadster.

In these all-important discussions – which took place in the small development department – Lyons, Heynes and Hassan were joined by Claude” Baily, former assistant chief designer of Morris Motors, who had arrived in 1940 to take charge of engine design development. As the Standard-based engines were clearly reaching the end of their production life, the team’s aim was to produce a power unit which, in Heynes’ words, would ‘… need to be capable of propelling a full size saloon at a genuine 100mph in standard form and without special tuning’. Although a four-cylinder, V8, six and even a V12 were considered, the team eventually decided that to produce the necessary 160bhp, an engine with a high-efficiency hemispherical cylinder head, with inclined overhead valves, would have to be employed. From 1943 experimental units were built, all prefixed X for Experimental.

The XF was a l,360cc four to prove the viability of the concept. The XG was, in effect, a l,996cc Standard four fitted with a cross pushrod head of the type used so successfully on the pre-war BMW 328 sports car – though this proved to be excessively noisy when tested in a saloon. The XJ was an 80×98mm l,996cc four and many of the experiments with port and head design were undertaken on this unit. The XJ prefix was also used on the first six-cylinder and was intended to replace the existing 2.5- and 3.5-litre engines with a single unit. However, it was found that it suffered from poor low speed torque and, at Harry Weslake’s suggestion, the stroke was increased from 98 to 106mm while the bore remained at 83mm, giving a capacity of 3,448cc. An aluminium cylinder head was standardised while at the other end of the unit, the substantial crankshaft ran in seven main bearings. This became the definitive XK engine while the l,996cc four-cylinder version was also readied for production.

But the still small SS company was sailing in uncharted waters because the twin overhead camshaft engine had previously been confined to high performance sports and touring cars in the manner of the Italian Alfa Romeo or Bugatti from France. The only British twin-cam to have been built in any numbers had been the l,098cc Lagonda Rapier sports car of the 1934–1939 vintage (about 250 examples had been made). And from Lyons’ standpoint, the twin overhead XK engine had an added bonus in that it also looked good. Like Ettore Bugatti, he was a great believer in the merits of under-bonnet artistry. This, then, was the engine on which the firm’s post-war fortunes were to be built and it not only powered the projected big saloon but also the sports car line which culminated in the E-type.

With the coming of peace in 1945, Lyons was the first to recognise that the SS initials had become tarnished by their identification with the fanatical Nazi é;lite: ‘A sector of the community which was not highly regarded’ was how he later put it. So in April 1945, the month before the war in Europe ended, SS Cars became Jaguar Cars, a name which Lyons had prudently registered back in November 1937.

Jaguar had not restarted sports car production after the war but instead concentrated, from August 1945, on a mildly updated version of its 1938 saloon range of Standard-engined 1.5-, 2.5- and 3.5-litre cars. But post-war Britain was urgently in need of foreign currency and steel allocation was geared to export performance. Like the rest of the British motor industry, Jaguar had exported few cars pre-war, and the 1939 record figures only amounted to a mere 252 examples. Yet in the economically chilly post-war world, along with the rest of the British motor industry, Jaguar looked for the first time to a world market. As Lyons later remembered: ‘We set out to convince the Government that the models we had coming along would command a substantial export market.’ The firm’s export programme was carefully itemised and Lyons personally delivered this ‘… very elaborate brochure … to Sir George Turner, who was then Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Supply, and I elaborated verbally on our plans and obtained his promise of support. Within two weeks we received a permit for the full quota of steel for which we had asked.’

This commitment paved the way for an aggressive export programme. Jaguar cars were offered with left-hand steering for the first time in 1947 when about a quarter of output was sent overseas. Initially, cars went to such established empire markets as Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, but it was America which responded most positively to the Jaguar. However, the opening-up of this new transatlantic market eliminated the need for the smaller four-cylinder XK engine which was accordingly sidelined.

Although Jaguar’s first objective had been to develop a new 100mph (160kph) saloon (it finally appeared as the Mark VII in 1950), there was clearly a need for a stop-gap model. This appeared at the 1948 London Motor Show in the shape of the Mark V saloon range.

The Mark V, outwardly similar to its predecessor, had a new box section chassis which featured a Citroen-inspired torsion bar independent front-suspension system, designed pre-war by William Heynes, to replace the half elliptics used hitherto. But sharing Jaguar’s stand at the 1948 Motor Show was Jaguar’s new sports car, a magnificent bronze-coloured XK120, powered by the 3.4-litre twin overhead camshaft engine that had been developed for the big Mark VII saloon, which was still two years away.

Sir William Lyons (centre) inspects the cockpit of the D-type (XKC402) prior to the 1954 Le Mans race. Note the forward-opening bonnet and triangulated front framework, both features which were perpetuated on the E-type. The oil tank for the dry-sump oil system is in the foreground.

The XK120

The XK120 was based on a shortened version of the Mark V’s chassis and its lovely lines were inspired by a special open BMW 328 sports car, run by the German company in the 1940 Mille Miglia race. That particular BMW was brought to Britain after hostilities by H J Aldington, the pre-war importer of BMW cars, and loaned to the industry for evaluation. One of the firms to examine the 328 was Jaguar, as it was a model which Lyons held in high regard, and he was able to use its lines as the basis for his new sports car. But the XK120, so named to respectively reflect its engine and top speed, was also significant in another dimension. It represented a milestone in British sports car design as a comfortable, well-equipped car which flew in the face of its stark, back-jarring predecessors. The model was in instant demand, particularly in America, and the car’s success took Jaguar by surprise. The first 240 examples were aluminium-bodied and hand-built in the customary prewar coachbuilding traditions. Consequently, Pressed Steel took over responsibility for the XK120’s body which became an all-steel structure.

This model, in turn, led Jaguar to the famous and demanding Le Mans 24-hour race, which had restarted after the war in 1949. For the 1950 event, three basically standard XK120s, unofficially sponsored by the factory, were entered. Two of them finished 12th and 15th, but although the third dropped out with clutch trouble in the 21st hour, it was in third place at the time, which convinced Lyons that: ‘In a car more suitable for the race, the XK engine could win this greatest of all events.’

Chief engineer William Heynes at the wheel of the unpainted prototype D-type (XKC401), at Browns Lane in April 1954. Later registered OVC 501, the car was used for testing and evaluating a De Dion rear axle.

The decision to enter an official Jaguar works team at Le Mans was not taken until October 1950 – the publicity benefits of a win there being enormous. But there were other reasons for entering a team of cars for the event and I can do no better than to quote Robert (Bob) Berry, a Jaguar employee of the day, who raced a lightweight XK120 himself and advised others who wanted to do the same. In 1976, Berry reflected that:

The 3.8-litre E-type just had the word ‘Jaguar’ on its rear but, by the time the 4.2 had arrived in 1964, it was so identified and ‘E-type’ was later added.

‘In retrospect three factors made the decision to continue inevitable. The first, and most obvious, was the degree of success achieved to date with relatively little in technical and financial resources. Secondly the [1950] Le Mans foray had shown that even the most respected names were far from invincible but thirdly, and overridingly, was the conclusion that the ever increasing level of opposition from full factory teams participating in relatively small events, was at last sounding the death knell in the era of the private owner.’

ON THE WAY TO THE E: JAGUAR’S SPORTS RACING LINE

The C-Type

The ‘more suitable’ car of which Lyons had spoken was William Heynes’ C-type. Its creation marks the starting point of a commission which evolved into the D-type and, ultimately, the E-type. A team of three Cs were rapidly prepared for the 1951 race. The intention was to produce a faster, lighter, more powerful version of the XK120 with a new, aerodynamically-improved body. All these objectives were met. In its roadster form, the XK120 was a 124mph (199kph) car, while the C-type could achieve 143mph (230kph). The XK120 turned the scales at 27cwt (1,371kg) while the C-type weighed considerably less at 20cwt (1,016kg). The XK engine developed 160bhp in the road car and developed 44 more at 204bhp in the sports-racer, while the sleek body lines were a considerable improvement on those of the production model.

Precious pounds were saved by Heynes adopting a multi-tubular space frame chassis. Front-suspension was essentially the XK120’s independent torsion bar system though, at the rear, there was a considerable departure from standard: the half elliptic springs were replaced by a single transversely-mounted torsion bar, connected to the live rear axle by trailing arms, while torque reaction members prevented lateral movement. Rack and pinion steering gear was a first for any Jaguar car. The C-type’s wheelbase was shorter than the XK120’s, being 8ft (2.44m) rather than the 8ft 6in (2.85m) of the road car.

The engines used in the XK 120s entered for the 1950 Le Mans race were carefully prepared for the event but were basically standard units. In the C, high lift camshafts were introduced, along with enlarged inlet valves. The inlet manifold was larger and 2in (50mm) SU carburetters replaced 1.75in (44mm) units. The compression ratio was upped from 8 to 9:1.

The creation of the C-type’s bodywork was the first assignment tackled by thirty-four year old Malcolm Sayer, an aerodynamicist from the Bristol Aeroplane Company who had joined Jaguar in 1950. Sayer’s brief was to design an aerodynamically more efficient body while still being identifiably related to the XK120. The aluminium body which resulted was produced in three sections, with the bonnet hinging at its forward end while the rear could be easily detached to reveal the rear-suspension.

Although two of the three C-types dropped out of the 1951 Le Mans race, a third, driven by Peters Walker and Whitehead, won the event at a record speed of 93.49mph (150.45kph). It was the first British win at the Sarthe circuit since a Lagonda victory in 1935. The C-type was less lucky in 1952 when last minute alterations to the front of the bodywork resulted in severe overheating and none of the cars finished. The 1953 cars were essentially restatements of the 1951 theme, though they were lighter with 18 rather than 16 gauge tubing. The 220bhp engines sported triple twin choke Weber carburetters, while all-round Dunlop disc brakes, pioneered in competition in the previous year, were employed – as were rubber weight-saving aircraft-type fuel tanks, made by ICI. The 1953 Le Mans race proved to be a copybook event for Jaguar and the C-types came in first, second and fourth.

The ‘C/D’

The C-type model was beginning to show its years and in 1953 Heynes and his team produced one example of a new car that can retrospectively be seen as a stepping stone between the C-type and its D-type successor and which also contains the first flickerings of the E-type’s sensational body lines. This was chassis XKC 054, which was known as: ‘The light alloy chassis XP11.’ For many years this car was thought to have a C-type chassis but, according to Bob Berry, Heynes, in his search for reduced weight, was led ‘… to investigate the advantages of monocoque construction using magnesium alloys for such frame components as there were and, of course, for the body. The techniques of welding structures of this type were in their infancy and to prove both the theory and the practice, a guinea pig was built.’

A D-type in action. Duncan Hamilton at the wheel of his car (XKD601) pictured in the 1958 Tourist Trophy race at Goodwood, which marked his retirement from competitive sport. Hamilton shared the driving with Peter Blond and was placed sixth.

Almost certainly the ‘Pop-Rivet Special’, photographed in 1959. While the overall E-type shape appears to have been finalised, much of the body trim has yet to be decided: the air-intake lacks its decorative bar, there is no chrome trim around the headlamp covers and no door handles nor permanent sidelights. The bonnet was secured by an exterior handle in the manner of the D-type.

It was fitted with the engine from the C-type used by Stirling Moss, which was placed fourth in the TT race of the previous month. Malcolm Sayer came up with a new lightweight body, looking lower and smoother than that of the C-type and, in retrospect, very ‘D’; particularly around the front end. On 20 October 1953, as a Motor Show publicity exercise, this car was taken to the Jabbeke motorway in Belgium, where it was fitted with a transparent wind-cheating cockpit bubble and, with Jaguar’s test driver Norman Dewis at the wheel, clocked 178.3mph (286kph), over the measured mile. In a final run over the flying kilometre, Dewis averaged 179.81mph (289kph); so the XP11 was the first Jaguar ever to exceed 180mph (289kph). However, this achievement was overshadowed by Dewis attaining 172.4mph (277kph) in a specially prepared XK120, also complete with bubble, which was the highest speed ever recorded by an XK120.

The XK120C 11, retrospectively referred to as the ‘C/D-type’ at Jabbeke, Belgium, on 20 October 1953. From left to right: Jaguar’s aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer, Jaguar mechanic Len Hayden, driver Norman Dewis, and, checking the front tyre, David ‘Dunlop Mac’ McDonald.

But impressive as the ‘C/D’ had been, Heynes and his team were convinced that a completely new sports-racer would be needed if Jaguar was to maintain its Le Mans successes and it was this decision which led to the creation of one of the most legendary sports racing cars of all time: the Jaguar D-type.

Malcolm Sayer (1916–1970)

Jaguar’s aerodynamicist joined the company in 1950 via that great repository of engineering talent, the Bristol Aeroplane Company. Sayer was responsible for the lines of some of the most famed Jaguar cars of the post-war years, the C- and D-type sports-racers, and the E-type. He also styled (though he never used the word) the still born XJ13 Le Mans car and the current XJ-S.

Born in Cromer, Norfolk, Sayer won a scholarship to Great Yarmouth Grammar School. He received his technical education at Loughborough College and, in 1938, although he had studied automobile engineering, joined the aero engine division of the Bristol Aeroplane Company because it offered better pay and opportunities than the motor industry. Sayer spent the next ten years at Bristol where he became steeped in the world of aerodynamics though cars briefly intruded when he designed the bodywork for the short-lived, locally-built Gordano sports car of 1947. In the following year, he took a job at Baghdad University to establish a chair in engineering, familiarising himself with Arabic on the boat to Iraq. Lack of facilities and political uncertainties resulted in his return to Britain in 1950, and for a job with Jaguar.

Drawing on his experience with Bristol, Sayer was responsible for introducing Jaguar to the world of aerodynamics with its use of wind tunnel facilities and smoke testing. Chief Engineer Heynes considered him: ‘A strong and generous character [who] was, nevertheless, quietly spoken and almost unruffled by the turbulence that is characteristic of the car industry.’ One of Sayer’s favourite stories was when he was flying back from Le Mans with Lyons in a Bristol Freighter, which he knew intimately. Sayer carefully explained to him that the engines were only secured by four 5/16 in (12.7/38.6 cm) bolts. This knowledge rattled the usually imperturbable Lyons, who thoroughly disliked air travel!

Over six feet tall, this charming, talented engineer succumbed to heart disease in 1970 and died at the early age of fifty-four.

The D-Type

If the C-type represented a demonstrable starting point for the E-type project, then the D can be considered to be the source of its structural origins, so its construction is of considerable relevance to our story. Once again the Jaguar design team strove to reduce weight, increase engine power and improve aerodynamics.

The tubular frame of the C-type was dispensed with. Instead Heynes created a monocoque tub of rivetted aluminium panelling – with appropriately-shaped openings for the driver and passenger – which was built-up around two hollow sills with substantial bulkheads front and rear. At the front, the engine/gearbox unit, suspension and steering were carried on what was, in effect, the framework of an oblong box with its four principal members of square section magnesium tubing passing through the top front bulkhead and argon arc welded to the rear bulkhead. Additional reinforcement came from a secondary A-shaped frame, mounted on top of it, but anchored to the front rather than to the rear bulkhead. The wishbones and longitudinal torsion bars were essentially carried over from the C at the front while the rear-suspension, though different, was also clearly related to its sports-racer predecessor. The suspension medium was once again a single transversely-located torsion bar and there were four trailing arms forming, in side view, a true parallelogram. Transverse location of the live axle came from an A bracket. As on the C-type, Dunlop disc brakes were fitted front and rear, though the C’s wire wheels were not perpetuated but replaced by alloy discs from the same manufacturer. Rack and pinion steering was also retained. With a wheelbase of 7ft 6in (2.29m), the D was 4in (101mm) shorter than the C.

The engine was essentially that of the C-type, though the valves’ sizes were increased. The triple Weber carburetters were retained though they were 1.77in (45mm) units rather than the previous year’s 1.57in (40mm) ones. With the intention of increasing both engine speeds and bearing loads, a dry-sump lubrication system was employed and, in Heynes’ words, ‘… overcame the disadvantage of having a lot of loose oil floating about inside the engine’. As a result of these ministrations, the D-type’s engine developed 240bhp. In the interests of weight saving, there was no flywheel: mass came from a vibration damper mounted on the front of the engine, the clutch, and the flywheel. An aluminium radiator was fitted for the same reason. The engine was mated with a new all-synchromesh gearbox and it is interesting to record that bottom gear synchro did not reach a Jaguar road car until 1965: eleven years later!

When it came to the bodywork, Sayer once again displayed his mastery although, as will emerge, the D-type was not quite the aerodynamic tour de force that it was considered to be at the time. The D’s bodywork was a perpetuation of the lines that Sayer had begun with the so-called ‘C/D’ of 1953 and it should be recorded that its shape was influenced by the experimental 1952 Alfa Romeo Touring-bodied Disco Volante.

One of Malcolm Sayer’s visual influences of 1952 was Alfa Romeo’s Colombo-designed experimental Disco Volante (Flying Saucer) sports-racer. The wind tunnel-tested body lines were executed for the Milan company by Carrozzeria Touring.

Sayer never considered himself to be a stylist, always an aerodynamicist, and he developed his own unique method of producing a body shape. Stylists usually start with a series of sketches but Sayer’s approach was essentially a mathematical one. His starting point was the four parameters of length, width, height and ground clearance. Having fixed these, he would create the car’s basic outline, using an elementary formula for an ellipse, and would then produce his lines on a drawing board. Then, once the car’s side, plan and head-on views had been created, he would continue to employ the same formula to build up the entire surface of the car. These calculations would then be confirmed by 1:10 scale wind tunnel models.

In applying these methods to create the D-type’s lines, he produced one of the most visually impressive cars ever built though, surprisingly, when an early full-sized example was tested in the Royal Aircraft Establishment’s Farnborough wind tunnel, it was found to have the not particularly impressive drag coefficient of 0.50, or about the same as the original Volkswagen Beetles! This figure was essentially confirmed in 1982 when Autocar magazine submitted the original design’s long-nosed successor to testing at the Motor Industry Research Association’s (MIRA) wind tunnel where it recorded a figure of 0.489.

Like the C-type’s, the D’s body was made in three sections: a forward opening bonnet, a centre section and a detachable tail. There was a stabilising rear fin which also concealed the petrol filler cap. The latter fed the twin flexible petrol tanks, containing 37 gallons (168 litres) of fuel, of the type pioneered on the C-type. This helped to contribute to the D’s impressive 17cwt (863kg) kerb weight, 3cwt (152kg) less than the C’s. Top speed was in excess of 170mph (273kph).

Bob Berry, who raced a privately-entered D, has recorded his impressions of driving this incredible car: ‘From my own experience, I can vouch for the fact that, at speeds of over 170mph (273kph), it was possible to sit in the cockpit, relaxed and in relative silence in an envelope of near still air, steering the car with no more pressure than finger and thumb. Especially in the dark the effect was both uncanny and deceptive, the real speed effect coming as a real shock as, on the straight, one rushed past other cars of nominally similar performance.’

A team of three D-types was entered for the 1954 Le Mans race, which developed into a memorable battle between the 4.9-litre Ferrari – driven by Gonzales and Trintignant – and the Jaguar D-type – driven by Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt. While the Italian car was able to out-accelerate the 3.4-litre D-type up to 100mph (160kph), the Jaguar was able to steadily draw ahead above that figure. As it happened, the Ferrari won at 105.09mph (169kph) with the Jaguar less than two minutes behind. The other two D-types had dropped out, though a Belgian-entered C was placed fourth.

The 1954 Le Mans race told Jaguar that more power would be needed for 1955. Valves were once again enlarged, though this necessitated redesigning the entire cylinder head, as the exhaust valves – their inclination changed from 35 to 40 degrees – would otherwise have touched the inlets opposite. Higher lift camshafts were also fitted, all of which combined to increase bhp once again: this time to 270.

In addition to these modifications, minor changes were made to the D’s structure. The front framework was altered so that its principal members were bolted, rather than welded to the bulkhead. Now only two tubes passed through the monocoque which was similarly bolted in place. This made repairs a far more practical proposition, as it was now possible to detach the power train from the central monocoque with a set of spanners. The square section tubes were also changed from magnesium alloy to nickel steel at the same time. Externally, the front of the car was also modified and extended by 7.5in (190mm) to improve airflow. The so-called ‘long nose’ also incorporated twin air-ducting to the front brakes.

Once the 1955 Le Mans event had begun, it had all the makings of a tremendous tussle between Mike Hawthorn in a D, and Juan Fangio at the wheel of a 300SL Mercedes-Benz, which led for the first nine hours. It quickly became obvious that, while the Jaguar was faster on the straight parts of the course, the Mercedes-Benz’s independent rear-suspension gave it the decisive advantage coming out of the corners. However, the event was clouded by the tragic accident which killed eighty-one people and led to the withdrawal of the Mercedes-Benz team soon after 2am on the Sunday morning. This left the Hawthorn/Bueb’s D-type to take the lead and it went on to win, with a Belgian-entered D taking third place.