Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

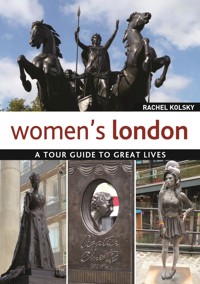

- Herausgeber: IMM Lifestyle Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

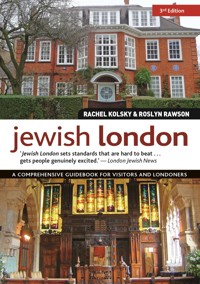

Jewish London is the only travel guidebook that focuses on the sights, heritage and culture of London's historic and present Jewish community. Packed with fascinating and practical information, it features everything for the visitor to London, from walking tours of historic areas such as the old Jewish East End to listings of kosher restaurants and shops, and information on important Jewish Londoners and where they lived, complete with plenty of specially commissioned maps. It is also an extremely useful compendium of information for the Jewish resident in London, listing Jewish cultural and heritage organisations, synagogues, ritual baths and other important Jewish centres, and a calendar of Jewish festivals and events in London. The extremely knowledgeable authors are Jewish historians and tour guides, and their lively, interesting text is illustrated with brand-new full-color photography of the most important Jewish sights.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 336

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedication

Rachel: To Ma and Pa, who instilled in me their love of London and Jewish heritage.Roslyn: To my husband, Jon, and my mother, Angela Davidson, whose input, love and support I found invaluable.

3rd Edition published 2018 — IMM Lifestyle Bookswww.IMMLifestyleBooks.com

IMM Lifestyle Books are distributed in the UK by Grantham Book Service, Trent Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 7XQ.

In North America, IMM Lifestyle Books are distributed by

Fox Chapel Publishing, 903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552.

Copyright © 2012, 2015, 2018 Rachel Kolsky, Roslyn Rawson, and IMM Lifestyle Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

Print ISBN 978-1-5048-0099-0

eISBN 978-1-6076-5567-1

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Although the publishers have made every effort to ensure that information contained in this book was researched and correct at the time of going to press, they accept no responsibility for any inaccuracies, loss, injury or inconvenience sustained by any person using this book as reference.

Picture Captions

Front cover top: Freud Museum;front cover bottom: Sukkat Shalom Reform Synagogue; back cover: Battle of Cable Street mural; page 2: Interior of New West End Synagogue, Bayswater;page 5 from left to right: Selection of bagels, Hendon Bagel Bakery; Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor; King’s College Chapel, Strand, Science Faculty window with depiction of Rosalind Franklin; Sandys Row Synagogue, photo – Jeremy Freedman.

contents

Introduction

How to Use This Book

Historical Overview

Jewish London on Foot

Old Jewish East End Walk

Angels and Radicals Walk

In and Around Commercial Road – Jewish Whitechapel Walk

An East End Village Walk

East End Synagogues

Fitzrovia and Soho Walk

Mayfair and West End Walk

Disraeli’s London

Jewish City – A Walk of Jewish Firsts

Mittel Europe in NW3 Walk

Hidden Jewish London

Notting Hill and Bayswater

In the Footsteps of Lily Montagu

Holland Park and Maida Vale

Off the Beaten Track

Jewish Museum

Holocaust Memorials in London

Czech Memorial Scrolls Museum

Art and Artists

Judaica in London

The Rothschilds in London

Jewish Londoners – Where They Lived

Jewish Londoners – Where They Lie

Jewish London Today

Central London

Golders Green

Smoked Salmon and Cream Cheese Bagels

Hampstead Garden Suburb

Temple Fortune and Finchley

Hendon

Edgware and Stanmore

St. John’s Wood

Hampstead, Belsize Park and Cricklewood

East London and The City

Stamford Hill

Educational and Cultural Jewish London

Day Trips from London

Glossary

Credits

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

The Jewish presence in London dates back to the 11th century. Today, there is a flourishing Jewish community numbering around 196,000. Whether you visit Golders Green with its bagel and falafel bars, Stamford Hill with its growing Orthodox community, Spitalfields with its memories of the Jewish East End, the City to trace civic emancipation through the lives of 19th-century financiers or stroll through leafy NW3 in the footsteps of refugees fleeing Europe in the 1930s, this book is the perfect guide to take with you to discover Jewish London through the centuries to the present day.

Divided into 11 chapters, the book includes ‘Jewish London on Foot’, a series of walking tours based upon Rachel Kolsky’s experience as a Blue Badge London Tourist Guide. There are also chapters exploring places of Jewish interest off the main tourist trail, an in-depth look at the Jewish Museum, features on Holocaust memorials, art and artists, literature and film, a calendar of cultural events and festivals and a chapter with suggested day trips from London. ‘Jewish London Today’ takes an independent look at contemporary Jewish London, providing listings for cafés and restaurants, shops, hotels, synagogues and religious amenities in the main Jewish areas within close proximity to Central London.

This book is for anyone who has an interest in Jewish life in London – past and present.

Enjoy!

Wall of Scrolls, Czech Memorial Scrolls Museum (see here).

Cable Street Mural, detail (see here).

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

Whether a local or a visitor, you will find Jewish London informative and easy to use. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information provided is up to date but restaurants and shops can close, galleries change their displays and opening hours and prices can vary. Basic opening-hours information for most listings is given but places often close on public holidays, Jewish festivals, etc. so call or consult websites before visiting. Unless otherwise stated, admission to the museums, galleries, etc. is free.

Telephone numbers provided are for calls made within the UK. For calls to the UK from outside the UK, the country code is 44 and the first ‘0’ should be omitted. For example, a call to 020 8343 6255 from USA/Canada will be 011 44 20 8343 6255, and from Europe/Israel will be 00 44 20 8343 6255.

Some Hebrew terminology is included. Please refer to the Glossary on here.

CAFES, RESTAURANTS AND SHOPS

Most of the cafés, shops and restaurants listed in this book are kosher. In the listings we state which kashrut authorities provide their licences and supervision. They are shown by the following abbreviations:

LBD – London Beth Din Kashrut Division: affiliated to the United Synagogue (020 8343 6255; www.kosher.org.uk).

SKA – Sephardi Kashrut Authority: under the auspices of the Sephardi Beth Din (020 7289 7663; www.sephardikashrut.org).

Kedassia – the kashrut division of the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations and Adath Yisroel representing the haredi communities in the UK (020 8349 9160; email: [email protected]).

West London Synagogue (see here).

KF – under the auspices of the kashrut division of the Federation of Synagogues Beth Din (020 8202 2263; www.kfkosher.org.uk).

LBS – London Board for Shechita: licences kosher retail butchers to provide fresh meat and poultry, and provides kashrut seals for pre-packed kosher products (020 8349 9160; www.shechita.co.uk).

For more information see www.hechshers.info.

The Really Jewish Food Guide published regularly by the London Beth Din provides a comprehensive guide to thousands of approved products, and monthly updates are available on www.kosher.org.

All the cafés and restaurants mentioned in ‘Jewish London on Foot’ (see here) are unsupervised unless otherwise stated.

SYNAGOGUES

Synagogues mentioned in this book are either independent or members of, or affiliated to, the following organizations:

United Synagogue: founded in 1870, this is the largest UK synagogal organization, currently comprising 62 Modern Orthodox synagogues (www.theus.org.uk).

Federation of Synagogues: established in 1887 as an umbrella organization for the growing number of small Orthodox immigrant communities. It currently comprises 23 Orthodox synagogues (www.federationofsynagogues.com). (See here.)

Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations: founded in 1926 to protect traditional Judaism, it acts as an umbrella organization for the Haredi Jewish community, including the Adath Yisroel synagogues.

Masorti: The New London Synagogue (see here), established in 1964, was the first Masorti synagogue. Masorti Judaism is devoted to traditional Judaism combined with a modern understanding of religious thought and practice. There are 15 Masorti synagogues in the UK (www.masorti.org.uk).

Reform Judaism: established in 1840, and currently comprises 42 synagogues in the UK. It states that its roots are in ancient Jewish tradition but that Jewish law has to be freshly interpreted in every generation (www.reformjudaism.org.uk).

Liberal Judaism: founded in 1902 and currently comprises over 30 synagogues in the UK. It states that it is the Judaism of the past in the process of becoming the Judaism of the future (www.liberaljudaism.org). (See here.)

Visiting Synagogues and Cemeteries

Synagogues are not generally kept open for visits outside service times although visitors are always welcome to attend services.

When attending services at an Orthodox synagogue you should dress appropriately. Men should cover their heads and women should dress modestly wearing a skirt or dress, not trousers. Married women should wear a hat. For services at Masorti and Progressive synagogues, the dress code is more relaxed but you may want to contact individual synagogues in advance to clarify. To avoid compromising standards of kashrut in the synagogue, food and drink should not be taken in. On Shabbat, the use of mobile phones and cameras is not permitted.

As Jewish burial grounds are also sacred places, the above advice for dress and conduct should be followed. Additionally, it is forbidden to walk over or step on any grave. On leaving a cemetery it is customary to wash your hands and facilities are made available.

TRAVEL INFORMATION

For most listings, the nearest tube station and approximate walking times are shown. Transport for London (www.tfl.gov.uk) is an excellent resource for planning how to travel between two locations.

MAP KEY

Walking route

Places of interest

Tube station

Overground station

Docklands Light Railway station Mainline station

Bus stop

Open synagogue – operating synagogue providing services and communal activities

Closed synagogue – closed to membership but the building remains

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The UK Jewish community currently numbers around 280,000, with approximately 70 per cent living in London. Other cities have a rich Jewish heritage but with their communities now depleted, it is in London where the buildings, associations and personalities who have shaped the community are concentrated.

The text that follows is a condensed history of Jewish London, from the 11th century to the present day.

11th–17th CENTURIES

Following the invasion in 1066, William I is credited with first inviting Jews to England when he needed to establish a system of credit. Communities were established in county capital towns such as Norwich and Lincoln but the main concentration for medieval Jewry was in London, in the area that is now the City of London. They worked as moneylenders and merchants but the community was not a ghetto. Street and church names in the City, such as Old Jewry, Jewry Street and St Lawrence Jewry serve as reminders, as no buildings remain. It was very exciting when a 13th-century Mikvah was discovered in 2001.

Edward I expelled the Jewish community in 1290, which by then had dwindled in number. During the subsequent period, known as the Expulsion, a small secret community remained. Other Jews, often doctors and lawyers, who were given royal protection, were able to reside in England more openly.

Oliver Cromwell allowed Jews to return in 1656 and, following this Resettlement, Sephardi Jews and then Ashkenazi Jews settled to the east of the City and beyond, where they established cemeteries, synagogues, businesses, hospitals and schools. By the early 1700s, the area around Aldgate was nearly 25 per cent Jewish. The wealthy soon bought palatial homes and country estates mostly to the north and south of London in Highgate, Totteridge and Morden.

Great Synagogue plaque, Old Jewry, City of London (see here).

1800s–EARLY 1900s

The move westwards also began and an Anglo-Jewish aristocracy developed in the West End including the Rothschilds and Moses Montefiore. By the mid-1800s, branch synagogues were built in the West End and North and South London suburbs. By the 1870s all the key Jewish communal initiatives had been established including The Jewish Chronicle, Board of Guardians, Board of Deputies and the Jews’ Free School (JFS).

In the 1880s, persecution of Jews in Eastern Europe led to tens of thousands of Jewish migrants arriving in London. They lived and worked near their point of arrival in the already crowded areas of Whitechapel and Spitalfields. A Jewish population of 125,000 with 65 synagogues was contained in 5sq km (2sq miles). It became the ‘Jewish East End’, with the sweated trades of tailoring, cap- and shoemaking, but vibrant street markets, youth clubs and Yiddish theatre also thrived. This life was replicated in the smaller community of Soho and Fitzrovia in London’s West End.

To relieve overcrowding, the community was encouraged to move east to Stepney and north to Hackney, then green suburbs. There was a distinct hierarchy within the Jewish East End – moving eastwards reflected upward mobility and school and housing costs reflected this.

Hackney-born Jews did not consider themselves Jewish East Enders. Theirs was a close-knit community with several synagogues, Ridley Road street market and Hackney Downs School, which at one time was 50 per cent Jewish.

Daniel Mendoza plaque in grounds of Queen Mary College (see here).

Stamford Hill and Stoke Newington also provided an escape from the East End. In the early 1900s, the furniture industry in Shoreditch and Bethnal Green moved northwards along the transport routes to Tottenham and Edmonton and new communities were established.

MID-1900s–21st CENTURY

The interwar years saw the first big changes to the Jewish community. Affordable housing built alongside new tube lines enabled an escape from the crowded East End to semidetached suburbia. The Northern line to Golders Green and Finchley and the Central line to Gants Hill and Ilford formed two geographically distinct communities. East End synagogues closed down and new ones were established in these suburbs while businesses typically remained in East London.

Hendon Reform Synagogue (now closed), stained glass windows

The 1930s saw a new group of Jewish immigrants; Austrian and German émigrés escaping Nazi Europe. Urban, educated, professional and assimilated, they did not go east but settled in NW3 and NW6, where housing was then cheap and plentiful. They quickly replicated their shops, restaurants and more liberal form of worship. Today, there is still a large Jewish community in these areas.

Following WWII, with mass evacuation and the loss of housing, the disappearance of the Jewish East End continued. People moved to new housing estates in Essex or remained in their evacuation homes and the JFS relocated to Camden, North London. In the 1950s, additional large suburban communities were established in Northwest London such as Stanmore, Kenton and Kingsbury.

By the early 1970s, with the second generation opting for the professions rather than working in ‘the family business’, the Jewish East End was nearly at an end. Soho and Fitzrovia followed the same pattern.

The late 20th century saw membership of North-west London synagogues decrease although the concentration of Jewish London facilities remains there. A proliferation of newer suburbs was established outside London including Bushey, Elstree, Radlett and Borehamwood, with a full range of facilities.

Into the 21st century Hackney hosts the vibrant and expanding ultra-orthodox community in Stamford Hill and inner suburbs such as Brondesbury and West Hampstead are experiencing a renaissance. One aspect unites the communities: they are composed, in the main, of the children and their descendants of the East European immigrants who were at the core of the Jewish East End.

JEWISH LONDON ON FOOT

London is a city best explored on foot. In many areas the networks of narrow streets provide the opportunity to discover less well-known buildings and the human stories behind them. This selection of self-guided tours is taken from the wide range that Rachel Kolsky has successfully led over the past 10 years. They focus on the East End, Central London and Hampstead; areas to which visitors and Londoners gravitate. On these walks, London’s Jewish communities over the centuries will be brought to life.

The walks start and finish near tube stations and approximate durations and distances are provided. All the routes are flat, with only a few involving some steps. These are mentioned, where appropriate, together with suggestions for refreshments. Each walk has a map indicating the route and places mentioned in the text, but you should take a detailed city map with you as well. The map below provides an overview of the location of the walks (and also the areas featured in the ‘Hidden Jewish London’ chapter).

The East End is larger than most people imagine, so it has been split into four walks. Each contains vivid memories of the long-gone Jewish East End and three include synagogues that have survived. The mural by Beverley-Jane Stewart on here captures the past and present of the Jewish East End, and incorporates many of the sites visited during the walking tours.

1 Old Jewish East End Walk (see here)

2 Angels and Radicals Walk (see here)

3 An East End Village Walk (see here)

4 In and Around Commercial Road – Jewish Whitechapel Walk (see here)

5 Jewish City – A Walk of Jewish Firsts (see here)

6 Fitzrovia and Soho Walk (see here)

7 Mayfair and West End Walk (see here)

8 Mittel Europe in NW3 Walk (see here)

9 Notting Hill and Bayswater (see here)

10 Holland Park and 11 Maida Vale (see here)

Story of East End by Beverley-Jane Stewart.

EAST END: OLD JEWISH EAST END WALK

This is the ‘classic’ old Jewish East End tour. Although the Jewish community may no longer live in Spitalfields, the streets and buildings still evoke memories of the synagogues, schools, shops and soup kitchens; not forgetting the street markets and the other immigrant communities who made this area their home.

START: Aldgate tube (Circle, Metropolitan)

FINISH: Spitalfields Market (near Liverpool Street station – Central, Circle, Metropolitan, Overground)

DISTANCE: 3.6km (2 ¼ miles)

DURATION: 1½–2 hours (allow longer if you want to browse the food shops on Brick Lane or visit Bevis Marks and/or Sandys Row synagogues)

REFRESHMENTS: Androuet (107b Commercial Street, E1 6BG; 020 7375 3168; www.androuet.co.uk) Specialist cheese and salads; Leon (3 Crispin Place, E1 6DW; 020 7247 4369, www.leonrestaurants.co.uk) Budget organic food; Or one of the many Bengali restaurants on Brick Lane

On leaving Aldgate station, turn right and walk a few yards to theChurch of St Botolph Without Aldgate.1Enter the churchyard and walk up a couple of steps.

The church, named after the patron saint of travellers, St Botolph, was built in the 1740s outside Aldgate, one of the seven gates in the second-century Roman wall surrounding the City of London. The plaque indicating the original position of the gate is near the corner of Aldgate and Jewry Street, so named to remember the pre-Expulsion Jewish community.

In the right-hand corner of the churchyard is a bronze-like sculpture of a crouching figure below a curved canopy. Called Sanctuary1A by Naomi Blake, it evokes the feeling of both being in need and protected (see here).

Retrace your steps and turn right out of the gateway of the churchyard. Pause by theMocatta Drinking Fountain.1B

In 1859 Samuel Gurney, a wealthy Quaker banker, established the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain Association to make a safe drinking supply available via a series of fountains issuing filtered water, complete with chained cup. Many of the fountains were funded in memory of eminent people. This one commemorates Frederick David Mocatta (1828–1905).

The Mocattas were one of the first Sephardi families to move to London following the Resettlement, establishing Mocatta & Co. in 1671. The company dominated the gold bullion trade. Frederick David Mocatta retired aged 46, devoting the rest of his life to philanthropy, including education, housing and administration of the Jewish community. His book collection was given to University College London where it was named the Mocatta Library (now the Jewish Studies Library). When there were calls for the immigrants from Eastern Europe in the late 19th century to be barred from entry to Britain he fought on their behalf pleading, ‘It is not for us as Englishmen to try and close the entrance into our country to any of our fellow creatures especially such as are oppressed. It is not for us as Jews to try and bar our gates against other Jews who are persecuted solely for professing the same religion as ourselves.’ Ironically, he died in 1905, the year of the Aliens Act, which brought in measures to reduce immigration.

Mocatta Drinking Fountain.

Cross the main road towardsBevis Marks. You will see Sir John Cass School. Turn right and continue to a large stone wall and look up. You will see a plaque to theGreat Synagogue, Duke’s Place.2

Today, modern office blocks predominate, but in the days of early Resettlement ‘Duke’s Place’ was used as a euphemism for the Jewish area of London. By 1714 around 25 per cent of the area was Jewish. Over 11 per cent of them worked in the local citrus market.

The Ashkenazi community established its first synagogue in 1690 in rented rooms at Duke’s Place. A purpose-built synagogue constructed in the 1720s was rebuilt in 1790 as a vast cathedral-like synagogue and, situated in a gated courtyard, had large plain glass windows on three levels. Membership included families such as the Rothschilds, and in 1809 three sons of King George III attended a Sabbath morning service as guests of the Goldsmids. There could be up to five bar mitzvahs on the same Sabbath morning and on Sundays there were queues of brides awaiting their weddings. During the Blitz of WWII it was badly damaged and despite plans for rebuilding, the much-reduced community instead rented rooms in the Hambro Synagogue, Adler Street (see here). The synagogue officially closed in 1977.

Continue down Bevis Marks and turn left intoCreechurch Lane. Continue until the junction of Bury Street and you will seea plaque to the first synagogue established after the Resettlement.3

By the end of 1656, the Sephardi community had acquired premises for use as a synagogue. Enlarged in 1674, it was used until new premises were built nearby in Bevis Marks. The 17th-century English diarist Samuel Pepys visited the synagogue on 14 October 1663 and his diary entry includes:

Thence home and after dinner my wife and I, … to the Jewish Synagogue: … Their service all in a singing way, and in Hebrew. … But, Lord! To see the disorder, laughing, sporting, and no attention, but confusion in all their service, more like brutes than people knowing the true God, … and indeed I never did see so much, or could have imagined there had been any religion in the whole world so absurdly performed as this …

Plaque to first synagogue following Resettlement.

He visited during Simchat Torah (Rejoicing of the Law) and would not have known such behaviour was unusual in a synagogue.

Retrace your steps down Creechurch Lane and turn left into Heneage Lane. At the end turn left into Bevis Marks. Continue until you see a pair of large gates on your left leading to the courtyard ofBevis Marks Synagogue4. During opening hours, enter through the gates to visit the interior. If the gates are shut there is a good view of the exterior. (See here.) On leaving, turn left into Bevis Marks. At the next junction, turn right at the traffic lights down St Mary Axe and cross Houndsditch. Turn right and then turn left into Cutler Street and stand in front of the tall warehouses.

Cutlers Gardens5 was originally a complex of warehouses built between 1771 and 1820 for the East India Company. Plain high walls protected valuable goods such as coffee, cotton and spices. Following the closure of the docks in the late 1960s, the warehouses were converted into offices and restaurants. From the early 18th century several small markets developed around Cutler Street, many dominated by Jewish traders. By 1850 over 50 per cent of ostrich feather trade and the military stores market were in Jewish hands and they also dominated the local diamond trade.

Beyond Cutlers Gardens you will see Devonshire Square6. In 1859, the Jewish Board of Guardians was established at No. 13 ‘to attend to the relief of the strange and foreign poor’. The Board worked tirelessly to improve sanitation, prevent disease and promote self-sufficiency. Between 1869 and 1882 around 2,000 cases were dealt with annually. Between 1896 and 1956 it operated from nearby Middlesex Street and was renamed the Jewish Welfare Board in 1964. In 1990, having merged with the Jewish Blind Society (established 1819), it became known as Jewish Care, caring for over 5,000 members of the Jewish community. In 1982 the headquarters moved to Golders Green.

If open, walk through Cutlers Gardens, turning first right, passing through a small gateway and turning left into Harrow Place. If Cutlers Gardens is shut, continue down Cutler Street turning left into Harrow Place. Pause on the corner ofMiddlesex Street.

The famous Petticoat Lane street market7 is here every Sunday. Well established by the 1750s, you won’t find the name on a map as the street was renamed Middlesex Street in 1830 to acknowledge the boundary between the City of London and the County of Middlesex. By the 1850s most of the goods sold were second-hand clothes. Cheap, mass-produced clothes predominated by the late 19th century, when the market was 95–100 per cent Jewish. On weekdays it sold general household goods. However, the Sunday market was unregulated and did not trade officially until 1936. In its heyday, the traders’ sales banter was like street theatre. The Sunday market covers an area embracing Middlesex Street, Cobb Street and Wentworth Street. Get there early, it begins to close down around 2pm.

Cutlers Gardens looking towards Devonshire Square.

BEVIS MARKS SYNAGOGUE

Completed in 1701, Bevis Marks is the oldest operating synagogue in the UK. Its plain exterior and large, clear windows are both characteristics of Sir Christopher Wren’s church architecture, and the architect, Joseph Avis, a Quaker, would have avoided ostentation. Above the central doorway are both the secular and Hebrew dates of opening, 1701/5462.

Step inside to see the wonderfully inviting interior, reminiscent of the Portuguese Great Synagogue of Amsterdam. The pews date from 1701 and there are original wooden benches from the Creechurch Lane Synagogue. Most striking are the seven brass chandeliers, lit by candle. It is believed that the largest was donated by the Amsterdam Sephardi community. Candle-lit services are still held for High Holy Days and special occasions. The large windows and chandeliers provided much needed light in the days before electricity. To the east, there is the Ark in a wooden cabinet resembling a church reredos. In front of the Tevah (Bimah) there is a grand chair for the Haham, the senior rabbi for the Sephardi community. To the side there are boxed and canopied pews for the wardens, unusual in English synagogues. Also visible are 10 large brass candlesticks and 12 pillars resembling marble, which are actually painted wood.

Exterior of Bevis Marks Synagogue.

In front of the Ark there is a chair with a rope across it. This was the seat of Moses Montefiore (1784–1885), the congregation’s most famous worshipper and only members of the Montefiore family, with rare exceptions, may use it. Montefiore made his fortune on the stock exchange. He retired in 1824 and devoted the rest of his life to philanthropic, communal and civic duties. His marriage to Judith Barent-Cohen in 1812 was groundbreaking as she was Ashkenazi. They were a pious devoted couple, with a home in Park Lane, Mayfair and a country estate in Ramsgate where they are buried (see here).

Another famous congregant was the young Benjamin Disraeli (1804–81), son of writer Isaac D’Israeli. However, following a disagreement between his father and the community, Isaac took his family in 1817, the year that would have been Benjamin’s bar mitzvah, to the Church of St Andrew Holborn where the children were baptized as Christians. This changed Benjamin’s life (see here).

Interior of Bevis Marks Synagogue.

Climb the stairs to the ladies’ gallery for a wonderful view of the interior. There are also painted boards listing previous presidents and wardens – many of the names remain in the community today such as Sassoon, Sebag and Montefiore. There is also a collection of beautiful mantle covers for the Torah scrolls. One is made from the silk of the wedding dress of Judith Barent-Cohen when she married Moses Montefiore.

There are still regular services at Bevis Marks (see here).

After browsing the stalls (if the market is open), continue upMiddlesex Street, and stop outside the Shooting Star pub. A plaque to theJewish Board of Guardians8indicates its second home after leaving Devonshire Square. Turn right intoWidegate Street. AtNo. 31see reliefs of bakers at work – a reminder of when the premises were once used by Levy Bros, matzah-makers established in 1710.Continue, then at the junction turn left intoSandys Row. Stop in front ofSandys Row Synagogue9on your right.

Sandys Row Synagogue. Photo Jeremy Freedman.

Founded in 1854 by economic migrants from Holland, this is London’s oldest Ashkenazi community. It is still functioning while almost all the other East London synagogues have closed (see here).

Continue to the end of Sandys Row. Turn right intoArtillery Laneand turn right intoParliament Passage. Turn left intoArtillery Passage, a narrow 17th-century alleyway, lined with cafés and shops. The hanging signs give an air of ‘ye olde England’. Exiting the alley intoArtillery Lane, seeProvidence Row, on the left. Now student accommodation, the original building was established in 1866 as a refuge run by Catholic nuns.Raven Row Gallery, with shopfronts dating from the 1750s, is to your right at No.56. CrossBell Lane, turn right intoTenterground, where early Flemish immigrants set their cloth out to dry, pulled taut over tenter pegs. Hence the phrase ‘to be on tenterhooks’ when feeling tense. Turn left intoBrune Street. Stop opposite theSoup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor.10

Previous premises were in Leman Street – where it was founded in 1854, Black Lion Yard and Fashion Street. The terracotta facia displays the secular and Hebrew year of building, 1902/5662. For Jewish immigrants who spoke only Yiddish, the relief of a steaming tureen of soup over the door indicates its purpose. Post WWII, the kitchen also provided a meals-on-wheels service to the elderly and infirm and finally closed in 1990. The premises have been converted for residential and commercial use. On the wall opposite the Soup Kitchen colourful panels celebrate the past Jewish and the current Bengali communities. Included are receipts for donations to the Soup Kitchen and extracts from Yiddish songs and Yiddish newspapers.

Jewish Soup Kitchen.

Facing the Soup Kitchen, to your left you will see a tall, blue, glass building. This was the site of theJews’ Free School.11

Developed from the Talmud Torah established by the Great Synagogue Duke’s Place in 1732, a new school opened in 1820 on Bell Lane. It was largely funded by the Rothschilds, who also provided ‘suits and boots’, spectacles and regular practical assistance such as teaching. By the early 1900s the school had become the largest in Europe, with over 4,000 pupils. Famous alumni include the writer Israel Zangwill, Professor Selig Brodetsky and the founder of De Beers, Barney Barnato. Most of the school was evacuated to Ely during WWII but did not return here. Re-established at Camden Town in 1958, it moved to Northwest London in 2002, with the uniform still in the Rothschild family colours of deep blue and gold. (See www.jfsalumni.com/history.)

Continue downBrune Street. Turn right intoToynbee Street. Stop on the corner ofWentworth Street.12

Wentworth Street remains part of the Petticoat Lane market complex and is open on weekdays. At the height of the Jewish East End it was also full of delis, kosher butchers (there were 15 in 1901), bakeries, costumiers and furriers, many remaining beyond the 1960s. The business names live on in the collective memory of London Jewry: Mossy Marks’s deli with Mr Mendel, the salmon cutter; Ostwinds the bakers, Bonn’s and Goide’s, both caterers; Shapiro Valentine, booksellers; and Bloom’s sausage factory.

Turn left and cross Commercial Street. Turn right into the gateway with the black-and-white ‘Tree of Life’ sign. This leads toToynbee Hall.13Walk through to the courtyard. (Note: this gate is sometimes locked.)

Opened in 1884 by Samuel and Henrietta Barnett, Toynbee Hall provided much needed resources to the predominantly Jewish local community. Classes including English, art and dressmaking were provided alongside free legal aid, country holiday funds and a toy library. Oxford University students were social workers living on site, hence it became known as a settlement. It was home to the world’s first Jewish Scout troop and they donated the small clock tower as a ‘thank you’. For over 75 years, until 2011, the Friends of Yiddish met here every Saturday afternoon. During WWII the Jewish market traders donated food and clothes to the distribution depot at Toynbee Hall and a plaque to Jimmy Mallon, a much-loved warden, can be seen. Toynbee Hall continues as a settlement in addition to social welfare activities. It was named after Arnold Toynbee, a noted historian at Oxford and a friend of the Barnetts who died young, a year before Toynbee Hall opened. In 1892 the Barnetts opened the Whitechapel Library and in 1902, the Whitechapel Art Gallery (see here).

Charlotte de Rothschild Dwellings arch.

Charlotte de Rothschild Dwellings by John Allin.

Retrace your steps and leave Toynbee Hall. Cross Wentworth Street and stopat thered brick arch.14

The arch with the inscription ‘Erected by the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company – 1886’ is all that remains of the first tenement block funded by Lord Nathaniel Rothschild’s housing initiative, named after the financial return on the investment. The block was called Charlotte de Rothschild Dwellings in memory of his mother and the first residents arrived in 1887. They were mainly, but not exclusively, Jewish. Built in plain yellow stock brick around a courtyard, the six-storey blocks were forbidding, and known locally as ‘The Buildings’. There was running water on all floors and the rent was affordable. An immediate success, they were quickly followed by the Brady (1890), Nathaniel (1892) and Stepney Green Dwellings (1896). By 1901, 4,600 people were housed in ‘Four Per Cent’ dwellings. Of the original four blocks only Stepney Green Dwellings (now Court) survives on its original site (see here). By the 1960s ‘The Buildings’ were in a bad state of repair and were demolished in 1976. They were replaced by the current social housing in 1984. Read the full story in Jerry White’s Rothschild Buildings.

Continue down Wentworth Street and turn left on toBrick Lane.15Stop by the arch.

Named after bricks originally made in the area, Brick Lane has for centuries been the backbone of immigrant communities. Erected in 1997 and painted in the colours of the Bangladeshi flag, the arch indicates you are now in ‘Banglatown’. Note the street signs in English and Bengali. Where you see Bengali shops and businesses, imagine when the street was almost entirely Jewish in character. Nicknamed the ‘Bond Street of the East End’, by the 1930s Brick Lane contained gownmakers, corset-makers, hosiers, boot and shoe dealers, milliners, tailors, trimming merchants and mantle-makers. Food establishments included Bloom’s at Nos. 2 and 58 and the ‘bagel ladies’, Esther and Annie, selling their wares straight from the sack.

Brick Lane.

Continue down Brick Lane. On the right, opposite the junction with Fashion Street, No. 54 isEpra Fabrics, the last remaining Jewish textile business, here from 1956 and still run by the Epstein family. Turn left intoFashion Street.16

Fashion Street.

Fashion Street has an ornate fascia, reminiscent of a Moorish bazaar, along its east side. This was the initiative, in 1905, of Abraham Davis, who wanted to provide a dry and warm shopping environment for the local street vendors. However, they preferred the outdoor life and the buildings reverted to wholesale, remaining as such until the recent renovation.

Fashion Street was home to two important Anglo-Jewish writers. Israel Zangwill (1864–1926) in his 1892 best-seller, Children of the Ghetto, vividly brings to life the Jewish East End of the late 19th century – the people, the festivals, the life cycle and the food. Zangwill was also a staunch supporter of womens’ rights (see also here). Sir Arnold Wesker (1932–2016), lived as a boy at No. 43 in the 1930s. Like Zangwill, he also wrote about the immigrant experience in his late 1950s trilogy of plays Chicken Soup with Barley, I’m Talking About Jerusalem and Roots. Chicken Soup with Barley, in particular, emotionally portrays life in the East End, exposing unrealized hopes and aspirations. His prolific output is often linked to political ideals. He was instrumental in establishing Centre 42, in 1964, putting into practice the trade union desire for access for all to arts and culture. (See also here).

Retrace your steps. Turn left into Brick Lane. PassChrist Church School17, rebuilt in 1873 with a drinking fountain in the wall. On the pavement is a replica manhole cover depicting crayons, one of several installed by the local council relating to cultural and social heritage. You will see more on the tour. Look up to see a drainpipe with aStar of David, a delightful memory of the Jewish community.

Stop on the corner oppositeBrick Lane Jamme Masjid (Mosque).18

Brick Lane Mosque.

This building captures the essence of the changing communities in Brick Lane. Look up and you will see a sundial dated 1743 with the inscription ‘Umbra Sumus’ (‘We are shadows’). It was built as a chapel for the French Huguenots (Protestants), who arrived fleeing persecution following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. After they moved west to Soho, the chapel was used from 1809 to 1819 by the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews. Unsuccessful, the society moved on and Methodists took over the building in 1819. In 1898 it became the Spitalfields Great Synagogue for the ultra-orthodox Machzikei Haddas ve Shomrei Shabbat (Strengtheners of the Law and Guardians of the Sabbath) congregation. With services almost around the clock, the congregation was renowned for its piety and strict adherence to orthodoxy. There was a Talmud Torah school next door on Brick Lane attended by over 500 boys. By the 1970s, the congregation had dwindled and in 1975 the building became a mosque.

Turn left intoFournier Street19and stop halfway down.

Built in the 1720s, these were homes for French Huguenots. With many working in the silk industry, the attic windows along the width of the houses, replicated at the back, formed large, light rooms for the silk looms. The detailing of the doorways and shutters is wonderful. Irish residents followed the French and in the late 19th century the Jewish community moved in. In each house several families could have been trying to eke out a living from the sweated tailoring trade. Post WWII, the businesses were mostly fur and leather. Following their closure, impoverished artists needing large but cheap light-filled studios arrived. No. 14, Howard House, dating from 1726, has an elaborate porch. Look also for the bobbin dangling between two windows on the first floor. One of several hung in 1985 by the council on houses known to have been lived in by a Huguenot family, it commemorates the 300th anniversary of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. No. 27 is one of the largest houses in Spitalfields. Between 1829 and the 1940s it was owned by the London Dispensary, becoming a garment factory until 1977. No. 29 was used as a synagogue. See the name sign of S. Schwarz at No. 33a.

Spitalfields’ houses.

CH N. Katz.

Retrace your steps to Brick Lane.

Opposite the junction with Fournier Street was Schewzik’s, the Russian Vapour Baths, named after the reverend who ran it. The busiest day was Friday for the men’s pre-Sabbath bathe.

Turn left into Brick Lane.

At No. 92 was CH N. Katz, which sold paper bags and string. It survived until the 1990s and the incoming art gallery has preserved the fascia.

Continue down Brick Lane and at Princelet Street look north and seeTruman’s Brewery. Opened in 1669 and brewing until the 1970s, the site is now a complex of galleries and cafés. Beyond, on a Sunday, you will find Brick Lane street market and an array of designer-makers and food outlets. Towards the top of Brick Lane at No. 159 is the24 Hour Beigel Bake(see here). Turn left into Princelet Street (previously Princes Street) and stop oppositeNo. 19.20See here.

Next door, No. 17 Princelet Street has a plaque to Miriam Moses21 (1886–1965) who was born here. She became the first female mayor of Stepney in 1931 and the UK’s first Jewish female mayor. She is most fondly remembered, however, for founding Stepney Jewish Girls’ Club in the mid-1920s (see here and here).

Miriam Moses, birthplace.

Continue up the road and stand outsideNo. 622, built in 1928. On the pavement you will see another manhole cover, depicting a violin.