Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

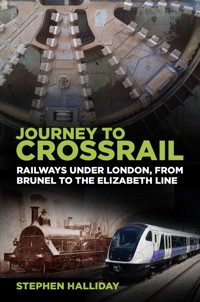

Why did London have to wait so long for a main-line railway beneath its streets? For a few years in the mid-nineteenth century, Isambard Kingdom Brunel's broad-gauge Great Western trains ran from Reading to Faringdon. Now, after many false starts, his vision is being realised as the Elizabeth Line prepares to carry passengers from Reading to the City once again, and beyond to Essex and Kent, using engineering that would have earned the admiration of the greatest Victorian engineers. London historian Stephen Halliday presents an engaging discussion of Crossrail's fascinating origins and the heroic engineering that made it all possible.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 191

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover illustrations: front, top: Greenwich Crossrail TBM, May 2013(DarkestElephant via Wikimedia Commons CC SA 3.0); bottom, left: ‘Fowler’s Ghost’; bottom, right: New Crossrail rolling stock, July 2017 (Sunil060902 via Wikimedia Commons CC SA 4.0); rear: Stratford Station, September 2011 (Ewan Munro via Wikimeda Commons CC SA 2.0).

First published 2018

The History PressThe Mill, Brimscombe PortStroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stephen Halliday, 2018

The right of Stephen Halliday to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9040 0

Typesetting and origination by The History PressPrinted in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction: A Long Time Coming

1 Steam Beneath the Streets

2 The World’s First Underground Railway

3 London at War

4 London Plans for Peace

5 Enter Crossrail

6 New Technology: Tunnelling Shields and Electricity

7 Mobile Factories Tunnelling Beneath London

8 Stations, Signals and Trains

9 Heroic Engineering

10 Crossrail Archaeology

11 Crossrail: The Future

Postscript

PREFACE

In the spring of 2014 I watched three programmes on BBC2 entitled The Fifteen Billion Pound Railway. They were about the construction of London’s long-awaited main-line railway running across the capital from Reading and Heathrow airport in the west to Shenfield in Essex and Abbey Wood, near London’s border with Kent. The programmes were amongst the best I had ever seen on television and I was particularly struck by the extraordinarily innovative engineering required to thread the tunnels through the maze of existing structures beneath London, and by the number of young women occupying key positions amongst the engineers involved in the project. I found this very encouraging. I live in Cambridge where I was also educated in the 1960s at a time when young women studying engineering at the university were rare indeed, less than 1 per cent of the total. The number is now approaching 25 per cent and rising.

I have previously written two books about London’s Underground railways and it occurred to me, while watching The Fifteen Billion Pound Railway, that the programmes would be a useful starting point for anyone thinking of writing a book about Crossrail. In 2017 I was asked to write just such a book so my first debt is to the Cambridge University Department of Engineering whose library has discs of the programmes, which I was able to watch three years after the programmes were first transmitted.

One of the most pleasing anecdotes of the programmes concerned the tunneller whose career was about to end with Crossrail, having begun over fifty years earlier with the Victoria Line but who was handing on the family occupation to his two sons, also working on Crossrail. I have often come across dynasties of teachers, soldiers and doctors, but the last dynasty of tunnellers was surely Marc Brunel and his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel; what an act to follow!

The other sources upon which I have depended in writing this account of Crossrail include Cambridge University Library; the books and leaflets produced by Crossrail as the work has progressed, most notably Platform for Design, the generously illustrated account of the ways in which the new stations were designed; the London Transport Museum in Covent Garden; my friend from schooldays David Brice, who started to work for British Rail when it was called British Railways and before Dr Beeching set about wielding his axe and is still active in studying and advising on railway development in remote corners of the world; and Nick Firman, who is now head gardener at my Cambridge College. He patiently explained to me why sedum plants are suitable for station roofs (as at Whitechapel) and showed me one amongst the unrivalled flora that he has cultivated at Pembroke College, where he has worked for fifty-four years.

My aim has been to demonstrate that Crossrail is the latest chapter in a story of heroic railway engineering involving imaginative solutions to problems that require a blend of intelligence, imagination, determination and money which began with the great Victorians and continues to this day. I believe that the current generation of engineers, men and women, are worthy successors to Marc and Isambard Kingdom Brunel; George and Robert Stephenson; and the many thousands of workers, skilled and unskilled, most of them nameless, who realised their dreams.

Stephen Halliday,Cambridge

INTRODUCTION

A LONG TIME COMING

For almost ten years Crossrail has been Europe’s biggest and most ambitious construction project, and certainly the one with the longest and most controversial gestation. For the first time, main-line trains will be able to run from east to west beneath the streets of the capital without passengers having to change from one train to another. It will be possible, and soon commonplace, for someone to board a train in Essex or Kent and alight at Reading or at Heathrow airport. Why would any travellers, in such circumstances, wish to submit to the perils and uncertainties of the M25? Yet, as we will see, the idea of boarding a train in Reading (or Bristol) and travelling by Great Western Railway broad gauge beneath London to the heart of the city can be traced back a century and a half to the time (and the brain) of Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1803–59). So it is perhaps fitting that one of the tunnel-boring machines (TBMs) that has brought his idea to fruition bears the name of his wife while another bears that of his mother. And it is not only Brunel’s legacy which the Crossrail project perpetuates. In preparing designs for the new stations for Crossrail the engineers, architects and artists have been following the precepts of Frank Pick (1878–1941) whose embracing of new ideas, from the London Transport Underground map to the adoption of new materials and models for stations, set new standards for public structures.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel against the launching chains of the SS Great Eastern at Millwall in 1857. (Photograph by Robert Howlett (1831–58))

The feats of engineering, finance and organisation which have brought about the project are themselves staggering. It will cost about £15 billion, with some of the money provided by the British government, some by Transport for London and some by the European Investment Bank; there will be contributions also from the owners of Heathrow airport and from the City of London. There will be 73 miles of railway line, 26 miles of which will be in new tunnels beneath London, with some beneath the Thames. The Crossrail Act, passed by Parliament in 2008, gave authority to Cross London Rail Links (CLRL) to build the system and to borrow the money to do it. The first shaft for the construction of the tunnels was sunk at Canary Wharf on 15 May 2009 in the presence of Transport Secretary Lord Adonis and the Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, and the tunnelling was finished at Farringdon on 23 May 2015 when the TBM Victoria broke into the eastern ticket hall of Farringdon’s new station. The end of tunnelling was officially acknowledged on 4 June 2015 in the presence of Prime Minister David Cameron, with Boris Johnson once again in attendance as Mayor. On 23 February 2016 the Queen attended a ceremony at the newly completed Bond Street station and unveiled a plaque revealing that, from the time it enters service in autumn 2019, the line will be known as the Elizabeth Line, with a London Transport roundel and bar to match. It will increase the capacity of the rail system in central London by a much-needed 10 per cent.

THE NETWORK

The tunnels are doubled throughout their length, like the Channel Tunnel, so that trains travelling in opposite directions will not see each other when running underground. The main tunnel runs from Royal Oak, near Paddington, to Stepney before splitting into two branches. One emerges from the tunnel at Stratford and proceeds thence to Shenfield in Essex where it connects with the Great Eastern main line. The other goes to Canary Wharf on the Isle of Dogs and passes beneath the Thames and on to Abbey Wood, where south-east London meets Kent and Crossrail meets the North Kent Line. In the opposite, westerly direction the line runs to Hayes where one branch takes trains to Heathrow and the other goes to Reading to connect with the Great Western main line. At present about 1.4 billion passengers use the Underground system and it is anticipated that many of the 200 million who are expected to use Crossrail would otherwise have used the heavily congested Underground network in Central London, thus providing much needed relief for services like the Central, Northern and Piccadilly Lines. It is hoped that the inclusion of two destinations at each end of the system, Reading and Heathrow in the west, Shenfield and Abbey Wood to the east, will ensure a balanced flow of traffic in each direction.

The Crossrail network will comprise forty stations, of which seven will be central and will incorporate artworks commissioned from well-known artists, funded by the City of London Corporation and other sponsors. These are: Paddington, Bond Street, Tottenham Court Road, Farringdon, Liverpool Street, Whitechapel, Canary Wharf.

All the stations are incorporated in or accessible from the existing stations which bear their names though major reconstruction has been required in most cases. In the central area trains will run every two and a half minutes and, besides taking pressure off crowded lines in central London like the Central and Piccadilly Lines, journey times will be dramatically reduced as shown in the following examples:

At present

With Crossrail

Abbey Wood to Heathrow

93 minutes

52 minutes

Paddington to Canary Wharf

34

17

Canary Wharf to Heathrow

55

39

Paddington to Tottenham Court Road

20

4

Some of the magnificent buildings at Canary Wharf, London’s new financial district in the former docklands. (Fidocudeiro via Wikimedia Commons CC 3.0)

And these times do not reflect the fact that, for instance, passengers travelling from Reading, Shenfield or Abbey Wood will not need to change trains in the central area as Crossrail will be a through service.

There will be a new depot at Old Oak Common, close to the Great Western main line west from Paddington, and a smaller maintenance depot at Reading. A plan for an additional depot at the eastern end of the network at Romford was dropped after a motion was tabled by MPs in the House of Commons opposing the plan, largely on environmental grounds. An existing depot at Ilford will be used instead. The line will be operated by MTR Corporation (Crossrail) Ltd on behalf of Transport for London, which is also responsible, under the Mayor of London, for the London Underground, the London bus services, taxis, river transport, the Docklands Light Railway and the suburban rail routes into the capital known as London Overground. It also administers the congestion charge and the so-called Boris Bikes (actually the brainchild of Ken Livingstone, Boris Johnson’s predecessor as Mayor), which are now sponsored by Santander. Services will begin from the central area in December 2018 and the entire system, from Reading and Heathrow to Shenfield and the rebuilt Abbey Wood station, is expected to be in operation by December 2019.

The so-called Boris bikes, which were actually conceived by Boris Johnson’s predecessor as Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, as a low-tech, pollution-free answer to London’s congested streets. Now sponsored by Santander. (Chris Mckenna via Wikimedia Commons CC 4.0)

THE TUNNELLING AND UNDERGROUND CONSTRUCTION ACADEMY

A most welcome legacy of the Crossrail project is to be found in Ilford, east London, in the form of the Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy which was completed in 2012 and trains employees in the skills and knowledge needed for the complex engineering work required to build, maintain and operate such a system. It is the only such institution in Europe and thereby helps to combat the shortages of engineering skills that are endlessly bemoaned by those who promote ambitious projects for which skilled staff are in short supply. More than 600 apprenticeships have been created to date, with an encouraging number of the places being taken up by young women. Fifteen thousand people have received training in such skills as the spraying of concrete lining for the construction of tunnels and stations. A laboratory has been created in the academy to study different types of tunnelling material. It will become the training centre for Elizabeth Line maintenance teams and for station staff, with twenty maintenance apprentices and a further 130 railway engineering apprentices. The facility will be managed on behalf of Transport for London by Prospects College of Advanced Technology which provides training on a nationwide basis for the engineering, aviation, rail and construction industries.

The Crossrail Act passed through Parliament in 2008 and eleven years later trains will begin to run. Compare that with the time it takes to decide to build an extra runway at Heathrow (or not, as the case may be); it’s quite quick. But if we look more closely, it has taken more than a century and a half from Isambard Kingdom Brunel to Crossrail and the Elizabeth Line.

1

STEAM BENEATH THE STREETS

‘If you are going a very short journey you need not take your dinner with you, or your corn for your horse.’

Isambard Kingdom Brunel in evidence to a House of Lords Committee, 30 May, 1854

WHAT DO WE DO WITH THE SMOKE?

The gnomic assertion above by the celebrated engineer of the Great Western Railway formed part of Brunel’s support for the idea of a main-line railway beneath the streets of London, which would enable his Great Western trains to transport passengers from Reading on the Great Western main line to the heart of the City of London without their having to endure the appalling congestion on London’s inadequate roads. His ambition, moreover, was briefly realised before being overtaken by events and has lain dormant for over a century and a half, to be finally realised when the Elizabeth Line, formerly known as Crossrail, enters service in autumn 2019 – a century and a half too late for the great Victorian engineer. As we will see, there have been many false starts for the running of main-line rail services beneath London.

At the time that Brunel spoke, the only effective mechanism for moving passenger trains was the steam engine which, besides producing steam to drive the wheels, also emitted smoke which, in the confined space of an underground railway, could be intolerable. Electric engines were still a gleam in the eye of Michael Faraday (1791–1867) and more than three decades would pass before the City & South London Railway, in 1890, became the first underground railway to use this form of propulsion. It is now part of the Northern Line. Other methods had been tried, notably by Brunel himself.

Michael Faraday, whose work on magnetism and electricity would eventually lead to an electric motor for railway trains, though not in time for the Metropolitan Railway. (H.W. Pickersgill via the National Library of Medicine)

A VACUUM-POWERED RAILWAY

In 1838 two engineers called Samuel Clegg and Jacob Samuda had patented the idea of a railway powered by atmospheric pressure. A cast-iron tube with a diameter of over a foot was laid between the rails. Within the tube was a piston attached by a rod to the underside of a train. At the end of the line a stationary steam engine pumped out the air in front of the piston, the resulting vacuum causing the piston, with the train attached to it, to be drawn along the rails. A demonstration railway 2 miles in length was built at Dun Laoghaire in Ireland, which made such an impression on Brunel that he asserted that ‘Mere mechanical difficulties can be overcome’, and he briefly adopted the system for the South Devon railway in the 1840s. The atmospheric pressure pumping house, now the home of a yacht club, may be seen in the small Devon community of Starcross, through which the railway ran between Exeter and Newton Abbot from 1846–47 at speeds of up to 70mph, much faster than a steam locomotive of the time could sustain. A section of the tube may be seen in the Great Western Railway Museum in Newton Abbot. Leather, beeswax and tallow were employed to create an airtight seal around the piston, but the beeswax and tallow melted in hot weather while the leather cracked in cold weather and had to be softened by the application of oil. Rats found the oily leather appetising and ate it, destroying the vacuum. In a further experiment on a railway between Croydon and Epsom the tube provided a popular home for more rats, who enjoyed eating the leather as much as their cousins in Devon had done. The South Devon Railway was 20 miles in length, more than twice as long as the underground line that Brunel had in mind from Paddington to the City, so if it had been made to work then Brunel’s proposal for a main-line railway beneath London would have been realised. But the rats caused the experiment to be abandoned in 1847 after only a year and with it went the chance of providing a steam- and smoke-free means of propelling trains beneath the streets of London.

Vacuum power: the tube along which a locomotive, attached to a piston, would be drawn along Brunel’s railway, if it weren’t for the rats! (Wikimedia Commons CC SA 3.0)

Starcross pumping house, Devon, which provided the power for Brunel’s vacuum-powered railway. it is now the home of a yacht club. (Geof Sheppard via Wikimedia Commons CC 3.0)

JOSEPH PAXTON’S GREAT VICTORIAN WAY

Despite these setbacks the ‘atmospheric’ form of propulsion rallied when it was proposed for two ambitious schemes to solve Victorian London’s transport problems. One, the Crystal Way, was that of an architect called William Moseley, who planned to build a railway 12ft beneath the streets, linking St Paul’s Cathedral in the City with Oxford Circus and Piccadilly Circus in the West End. Above the tracks would be a wrought-iron highway from which the trains beneath would be visible to pedestrians, who would also be able to visit rows of shops enclosed within a glass arcade – in effect a shopping arcade protected from the foul atmosphere of the capital with its smoke, fog and defective sewers. A similar arcade, also vacuum powered, though above ground, was proposed by Sir Joseph Paxton (1801–65) whose groundbreaking use of standard prefabricated components in cast iron and glass in the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851 had at first been condemned and later applauded. The techniques, sophisticated at the time, were later used for the conservatory on Canary Wharf Crossrail station, as described in chapter 8. The Parliamentary Select Committee on Metropolitan Communications was impressed by the ingenuity of the schemes but deterred by the huge cost of £34 million – think billions in twenty-first-century values.

Joseph Paxton’s use of prefabricated components for the Crystal Palace made possible the Great Exhibition of 1851 and inspired later designers, including those of Crossrail. His design for a great Victorian way encased in glass was less successful. (The Illustrated London News)

The Crystal Palace at its new home in Sydenham, where it was relocated after being dismantled and moved from the Great Exhibition site in Hyde Park. It was destroyed in a spectacular fire on 30 November 1936. (Philip Henry Delamotte, via Wikimedia Commons)

‘WHAT WE PROPOSE TO DO IS TO HAVE NO FIRE’

Brunel’s solution, as expressed in his evidence to the House of Lords, was an engine that would build up sufficient heat and steam before entering the underground section of the line so that it could complete its subterranean journey without the need to burn more smoke-creating coal. Hence his expression to the House of Lords Committee which opened this chapter: ‘If you are going a very short journey you need not take your dinner with you, or your corn for your horse.’ The engineer to the line, John Fowler, was equally emphatic in his evidence to the Parliamentary Committee which was considering the matter, informing them that locomotives could continue to run for some time after the fire had been extinguished:

What we propose to do is to have no fire … to start with our boiler charged with steam and water of such capacity and such pressure as will take its journey from end to end and then, by arrangement at each end, to raise it up to its original pressure … neither myself nor Mr Brunel nor any engineer would consider this as a matter of doubt. It is a mere practical mode of working.

John Fowler (1817–98) was one of the most prominent engineers of the Victorian age and possibly the most highly paid. Born near Sheffield, he trained on the Aire & Calder Navigation and on many railway schemes before being appointed Chief Engineer to the proposed Metropolitan Railway in 1853. He was later engineer also to the District Railway (now the District Line, with the Metropolitan and the District eventually being joined to form the Circle Line) and the Hammersmith & City Line. He was also consulted on railway projects in Algeria, Australia, Belgium, France and the USA. He became the youngest president of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1865 and was also Chief Engineer to the Forth Railway Bridge. Fowler’s earnings were legendary. He incurred the wrath of the equally colourful Sir Edward Watkin (1819–1901) in connection with Fowler’s work on the Metropolitan of which Watkin was chairman, earning the rebuke:

John Fowler: highly paid engineer to the Metropolitan, District and many other railways who incurred the wrath of Sir Edward Watkin for his enormous fees. (Lock & Whitfield, Wikimedia Commons CC 4.0)

Robert Stephenson (1803–59) was one of the greatest locomotive engineers of the age, the designer of Rocket and builder of ‘Fowler’s Ghost’, whose failure he did not live to see. (Tagishsimon, via Wikimedia Commons CC 3.0)

No engineer in the world was ever so highly paid ... you have set an example of charge [sic] which seems to have largely aided in the demoralisation of professional men of all sorts who have lived upon the suffering shareholders for the past ten years.

Fowler had been paid over £150,000 by the Metropolitan and a further £330,000 by the District Railway, huge sums at any time and monstrous in the nineteenth century, so Watkin had a point.