Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Old Pond Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

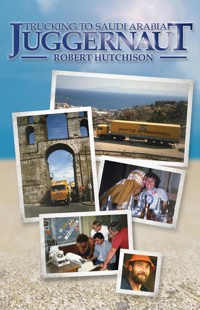

In 1986 professional writer Robert Hutchison became a passenger on a 10,000-mile trip through fourteen countries in a Scania 111. He was sampling the life of the long-haul trucker. The truckers' world was one of long days and nights on the road away from their families, hair-raising tales of accidents and the extreme danger created by murderous driving. He grew to understand why truckers put up with the life - not just for the money and the excitement, but also for their pride in coping whatever the circumstances and for camaraderie. There was, too, the beauty of mountains and lakesides and the strangeness of the desert. Robert's trip with Graham Davies of Whittle International took him through Cold-War Europe to Turkey and then through Iraq during the Iran - Iraq conflict with twenty-mile border queues and frequent police shakedowns. Finally they delivered their cargo of machinery and ovens for making plastic pipes to Al Khobar in Saudi Arabia before heading home after 31 days on the road. This journey was undertaken when the golden age of transport from Europe to the Gulf was coming to an end. Robert's accurate record, first published in 1987, is full of interest, drama and humour, telling the story of a remarkable breed of men. This is the first paperback edition.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 529

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Juggernaut

Trucking to Saudi Arabia

Robert Hutchison

This book is dedicated to Chris Lawrence and the other victims of theHerald of Free Enterprise disaster.

Jug.ger.naut: n. (from Sanskrit, Jagannatha, lord of the world) a terrible, irresistible force. Webster’s New World Dictionary, 1979, edition.

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

Dover Docks

GRAHAM Davies lit another cigarette, pushed his empty tea mug across the kitchen table, and looked at his watch. As an international freight driver, he saw his family less than a week in every month and getting back on the road again was never an easy matter. Once under way, though, he knew he would slide back into the routine of the road soon enough and everything would be all right. But the first few miles and the last few of every trip were always the most difficult because they seemed the longest.

Graham owned and operated his own truck, but contracted his services to a major freight forwarder, Whittle International Freight Limited of Preston, north-west of Manchester. The pressures of being a long-distance driver were as weighty as some of the cargoes he pulled, and the financial insecurity which seemed a part of being a diesel gypsy was turning his wife Madeleine into a nervous wreck. Earlier that summer, while Graham had been on the road, I had seen Madeleine sit for hours in their darkened front room, wondering how they were going to keep it all together. She blamed herself for the fact that they were hard up, but also she regretted that Graham had given up the taxi business. At least the taxis had paid good money, while it was a constant battle just to keep the truck on the road, with no cash left over at the end of a trip to pay off debts. Nor could she hide her apprehension about Graham’s next trip with me. She knew it would be more dangerous than his usual runs to Greece or Morocco. And she fretted, too, that as Graham would be away longer than normal the bank manager might cancel their £7,000 overdraft.

Angela, who was fourteen, and Jennifer, twelve, liked it when their father was at home. Mum was happier then and didn’t nag them as much. Of the five Davies children, they were the only ones still living with their parents. Their eldest sister, Stella, with two young boys of her own, was divorced and living near London. Martin was in Auckland with his New Zealander wife and baby. Julian, the manager of an exhaust repair shop, was married to a Blackpool girl and they had recently moved into their own home.

Around 3 p.m. Graham decided he could defer our departure no longer. We walked to the lane by Stanley Park where he parked his Scania 111 and drove it around to the house so that we could load our gear. Jennifer was crying. She didn’t want her father to leave.

‘Silly goose. Dry your tears,’ he told her. Graham was as sparse with his words as he was with his emotions. But I could tell she was tugging at his heartstrings. ‘That Jennifer,’ he said later, ‘she’s as daft as they come.’

We were in the north-west of England, where people undulate their voices like the sound of the sea, flattening vowels and rolling syllables, all the while deforming words and their meaning in ways that foreigners, whether from Cornwall, Connecticut, or the Charente-Maritime, find difficult to comprehend. For example, they call police cars jam butties. Now try and figure that one out, I told myself.

‘Why?’ I asked Graham.

‘Why what?’

‘Why jam butties?’

‘Because in Lancashire a buttie is a sandwich. A police car is a jam buttie because it is white and has a red stripe along its side,’ he explained, as if it were something everybody should know.

Another example was the Illuminations. It took me a long time to understand what Graham was referring to when he asked if I had seen the Illuminations. ‘They reckon it’s the greatest free show on earth.’

At first I thought it might be a local football championship – the eliminations – or maybe a collection of medieval manuscripts. But no, to attract Scottish tourists during the autumn off-season, Blackpool lights up its eight miles of seafront promenades, piers, and tower with multicoloured garlands, displays that explode in electric orgasms, and dancing laser beams that paint the sky. They can probably see the lasers bouncing off the ionosphere over in Ireland, and a good number of the Scottish tourists get so boozed they no doubt see the whole thing double. We had been the night before and, apart from the annoyance of being caught in an eight-mile traffic jam, watching the Scottish women sort out their menfolk had been as entertaining as the lights themselves.

Back in the front corridor of the Davies home, I handed boxes of food and equipment to Angela who carried them to her father. He stored them on the lower bunk of the Scania, behind the two seats: twenty-four boxes in all, plus the bags and briefcases containing our personal gear. Although the cab was seven feet wide and the bunk almost four feet deep, that didn’t leave us much room. Graham would sleep on the upper bunk; I had brought a sleeping-bag and some foam rubber insulation and was planning to sleep under or on top of the trailer, depending on the weather.

Unlike the French, who buy most of their food en route, British long-distance drivers buy everything they need for the trip from their local supermarket. Hence Graham and I had spent most of Saturday afternoon purchasing supplies of condensed milk, spam, Irish stew, tinned vegetables, more spam, tinned potatoes, packages of ersatz hamburgers, still more spam, instant noodles, black pudding, bacon, biscuits, chocolate, sliced bread, tea bags, and all the other things that British drivers like. The only concession I wrung from him was to add to our meagre store of utensils a pressure cooker which, French drivers swear, next to the jack, tyre iron and gas cooker, is a trucker’s best friend. I was determined to buy fresh produce along the way.

Another perversity I had noted about truckers is that invariably they named their beasts of burden after a woman, or at least something feminine. Graham called his Scania simply Old Girl because, he said, she was a good steady creature. To be more precise, Old Girl was really a tractor. Once she had a trailer behind her, she became a juggernaut. The British press gave the name to these forty-ton contraptions; it conjures up an image of some mighty, irresistible force, and that was exactly how I saw these rigs as they rushed along the narrow byways and highways of Europe.

We left Blackpool at 4 p.m. on 15 September, 1986, and bullied our way south through 200 miles of Sunday traffic to pick up our trailer at the Infrasystems factory in Luton, 30 miles from London. We reached Luton just before 9 p.m.

‘Damn,’ Graham said on our first pass in front of the factory. ‘They haven’t sheeted the tilt, have they?’

A tilt in the language of British truckers is a type of trailer built to international specifications. It can carry up to twenty-five tons of cargo on three back axles, and its metal frame is covered by canvas sheeting. Once loaded, the sheeting is drawn over the frame and laced to the bottom of the trailer by a single cable that runs from the front along both sides and joins at the back so that it can be sealed by customs officers for bonded transit through foreign countries.

Our tilt was standing in the shadows in front of the factory on the far side of the road. It was loaded with eight big pieces of loose cargo and assorted cases containing motors, jigs, conveyors, and a cardboard tube full of plans. Our manifest described it as ‘the dismantled parts of one automatic flood coater, one LPG-fired pre-heat oven, one automatic dip-coating device with fluidized bed, and one LPG-fired post-heat oven’. The total weight was listed as 5,050 kilograms.

‘Just enough to hold her on the road,’ Graham commented, referring to the lightness of the load. ‘Old Girl should like that.’

In fact we were pulling one-half of an industrial oven system. It was a one-off model, designed for coating and baking plastic pipes that would run through it on a conveyor belt. The unbaked pipes went in one end and thirty minutes later came out the other all shiny and orange. Our job, together with another Whittle International truck, was to deliver the complete system to the Saudi Conduit & Coating Company at Al Khobar, an oil port half-way down the Persian Gulf coast, opposite Bahrain. The other truck, driven by twenty-six-year-old Steven Walsh, was to join us in Belgrade on Thursday.

We anticipated that the trip to the Persian Gulf would take three weeks. We were going through East Europe to Yugoslavia, into Greece, then Turkey and Iraq, and finally to the Tapline across the Saudi desert. Counting our return through Jordan and Syria, we would transit fourteen countries and cover more than 10,000 miles. We would travel along trade routes that had been used for thousands of years – the same roads over which Persian armies and Roman legions had marched, and for control of which Crusader princes fought Arab caliphs, and which in some places are still being fought over by Turks and Kurds, Arabs and Iranians. We would pass through the city of Tarsus, where Saint Paul was born, Edessa, where Abraham was thought to have rested on his way from Ur to Canaan, and traverse valleys where the Assyrian hordes had once spread havoc.

A Total station stood next door to the Infrasystems factory and to foil stick-up artists the woman at the cash register was locked inside a bullet-proof glass cage. As Graham backed Old Girl up to the trailer, I noted she was selling diesel for £1.66 a gallon. In Saudi Arabia we would buy it for 10 pence per gallon, cheaper than water. Graham eased the ‘fifth wheel’, a greased circular platform, over the back axle of the tractor, onto the trailer’s locking pin. The mechanism snapped shut with a loud click but still he gave the trailer a tug to make sure it had locked properly. It had. We were now – tractor and trailer – 56 feet long, 12½ feet high, with five axles, twelve wheels, and a gross weight, supposedly, of 23 tons, 17 less than the maximum allowed on European roads.

Our next task was to ensure that the load was safely secured so that it would not shift during the journey. We climbed up the trailer’s sidegates and shook some pieces of galvanized panelling. They swayed back and forth like sheets in the wind.

‘That won’t do, will it? We’ll have to secure the lot,’ Graham announced.

We got the cargo straps and started tying down the bigger pieces. This would cost us a good hour of driving time and we were anxious to get to Dover. After straightening everything away, we pulled the canvas back over the top of the tilt and were preparing to ‘zipper’ it up when an Infrasystems engineer drove up. He asked if everything was in order. We allowed that it was. He knew we were to collect the trailer sometime after midday and had been driving by every hour or so, keeping an eye on it.

Once we got the oven to Al Khobar, the engineer and some of his mates would fly out to assemble it. ‘The only one like it in the world,’ he said. Infrasystems had designed and built it in the record time of three months. Graham retracted the trailer legs as I connected the air hoses and electric cable between the tractor and trailer. When we finished, our friend remarked: ‘Don’t worry about the whisky. They’ll never find it. We’ve really hidden it well.’

We thanked him, thinking this a joke. After all, he was laughing when he said it, wasn’t he? Back in the cab, we waved goodbye. It was now 9.50 p.m. and we were happy to be back on the road. It took about twenty minutes for the implications of the engineer’s remark to sink in. ‘Oh shit,’ I finally gasped. ‘Do you really think he was joking?’

‘Why?’ Graham asked.

‘Saudi is a dry country,’ I reminded him. ‘No spirits, no beer. You get thrown into prison, even lashed, for breaking the law.’

I didn’t mention that we also risked having the truck confiscated. This would be no small disaster for Graham. Old Girl had been freshly painted for the trip in Whittle International’s yellow livery and looked like a company wagon. But she was in every sense Graham’s only means of livelihood.

This was our first trip to Saudi. The year before we had driven together as far as Baghdad, carrying a dismantled banqueting kitchen for the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein, who was remodelling the presidential palace in the midst of his costly war with Iran. Al Khobar was fully one-third as far again.

Graham said nothing, weighing this potential dilemma in his mind. As the navigator and occasional co-driver, I could sit back and relax, watching the night lights flick by, half listening to the citizens’ band radio for warnings of ‘heavy metal’ and ‘pick-and-shovel’, meaning traffic jams and road works. Old Girl offered a bumpy ride. ‘It feels heavier than what’s marked on the manifest,’ Graham said. ‘Probably more like eight tons back there.’ Just then we blew an air hose.

‘Damn,’ he said. ‘We’ve lost the back brakes.’ But he was determined to roll on till we came to a roundabout with a diner on it, where we could stop for a cup of tea.

Graham was an oddity among long-distance truckers in that he rarely swore. The men who risk their lives on the Middle East run pride themselves on being among the roughest, raunchiest, most ornery drivers in the world. Many enhance their image by sporting tattoos, ear-rings, beer-bellies, and accordion wallets attached by a chain to large-buckle belts, and almost all have a vocabulary that would make a trooper blush. It is equally true that most are romantics at heart who become instant pushovers when treated with anything approaching respect; in fact, their hearts are often bigger than the turbos that run their trucks. Graham’s need for peer-identity stopped with the accordion wallet. He had no chain, ear-rings, tattoos or large-buckle belt, though he did own a collection of exotic T-shirts. These also are part of the uniform.

The most remarkable thing about Graham, as I had come to know him during the past year, was the image he cast of calm stoicism. Or was it just plain old stubbornness, for that too was a feature of his character? He stood perhaps five foot eleven inches, with a sturdy build. But because he was wedged behind the wheel of the Scania for long hours, he was not at a peak of physical fitness. The lack of exercise and pounding from the road had given him a paunch. He kept his dark hair short; as it was bushy and straight it didn’t need a lot of brushing. His skin, I noted, was easily irritated, which meant that in idle moments he would shave off any hint of stubble with an electric razor run off batteries. In the morning he groped about till he found his thin-rimmed glasses. But once awake, his eyes became quick with movement that matched an often wry smile. I imagined he must have been impish at school, giving his teachers a difficult time. He was rebellious, but to change rather than towards established authority, which made him a political conservative.

He had learned well the routine of long-distance freight driving, as for example in clearing customs. At each border the procedures were basically the same, though some of the wrinkles changed. When we arrived at Dover Docks he knew exactly what to do and in which order, like a jet pilot running down a checklist before take-off. It was midnight and hundreds of trucks were being disgorged from cross-Channel ferries, water pouring off their roofs. While the moon was still darting in and out of clouds over Dover, it was evidently a stormy night in Europe. Few trucks, we noted, were heading for the Continent.

Our first concern was to fill the belly tank under the trailer with three hundred gallons of diesel. It took an hour to raise the Dover Diesel Sales operator and then he charged us £1 a gallon for the tax-free diesel. This was no bargain. At least, though, we could proceed to the freight agent’s office.

As it was illegal to transport more than forty-five gallons of diesel in an open tank through West Germany, we had to fill out a T-Form, which normally covers the transport of goods inside the Common Market, stating that the diesel in the belly tank was part of the cargo which we were delivering to ourselves at Folmava, a town on the Czech side of the West German border.

So much for Common Market bureaucracy. We drove Old Girl into the customs bay where we presented the T-Form, an eight-page TIR carnet and our cargo manifest to a customs inspector. He placed lead seals on the back of the tilt and around the belly-tank spigot, then stamped our TIR carnet, removing the first volet or paper stub from this essential document issued by the International Road Transport Union (IRU) in Geneva, Switzerland.

TIR stands for Transport International Routier. An international convention, regulated and managed by the IRU, covers all TIR traffic. The convention guaranteed our cargo’s passage in bond through the seven IRU-member states we would transit on our way to Al Khobar. As Iraq and Saudi Arabia do not subscribe to the TIR convention, separate documents are needed for these countries. Customs officers in each of the IRU-member countries are supposed to inspect the seals to make sure that they have not been tampered with, and if the seals are intact then stamp our TIR carnet and remove two stubs – one upon entering and the other when leaving the country. These stubs will eventually be sent to IRU headquarters in Geneva. After the journey, when all the stubs are reunited with the used carnet, the IRU then retires the document, thereby liberating the customs bond.

Only once the cargo papers had a customs stamp on them, signifying the freight had been cleared for export, would the Townsend Thoresen ferrymaster sell us a ticket. He booked us on the 5.30 a.m. freighter to Zeebrugge in Belgium. With nothing more to do but wait, we went to The Barnacles, a truckers’ grub shop at the end of the docks, for a cup of tea and a toasted cheese sandwich. No sooner in the place than we noticed the mood was sullen.

‘What is it?’ Graham asked the girl who took our order. ‘Consternation,’ she said.

‘Consternation over what?’ I asked.

‘For ’im what died. ’Ee was missing two days. They found ’im this morning.’

It took a while, but finally we dragged the story from her. ‘’Ee was a right beefy lad,’ she said. ‘Good looking an’ all. Never’ave suspected ’ee was queer, like.’

The consternation, we gathered, was not over the fact that the fellow was now dead, but rather over the manner in which he had died. Not that foul play was suspected. Far from it. He had returned from the Continent late on Friday and logged in with customs, after which he went to The Barnacles for a meal and then disappeared. His vehicle was parked, curtains drawn and the doors locked. Customs agents hunted all over the docks for him to clear his load. When they pounded on his door, no one answered.

The harbour police finally pried one of the doors open. Inside, a macabre sight confronted them. The driver was stretched out on his bunk, behind the two seats, wearing a woman’s negligee and black silk stockings. He had a self-applied garrotte around his neck and apparently had accidentally strangled himself in an act of kinky self-abuse.

‘Twisted, he was,’ Graham quipped.

‘What do you mean?’

‘A real head-banger, wouldn’t you say?’

I agreed.

We finished our tea and decided it was time for a few hours’ kip. The wind was rising, with sand blowing across the docks, heralding a change in the weather. We had parked beside Ossie MacIntosh’s cream-coloured Ford Transcontinental. Ossie was a black giant of a man, with shoulders the size of an ox, but as gentle as a pussy cat in a fur slipper. In fact Ossie could be downright taciturn. But he was thoughtful of others, which made him one of the more respected drivers on the run to the Balkans and Greece.

CHAPTER TWO

Mosaic of Trade

THE ferry crossing took the normal five-and-a-half hours – time for a meal, a shower, and a sleep. As it turned out, Ossie MacIntosh was the only other TIR driver we knew on board. The rest were either T-Form Charlies – i.e. truckers whose routes were within the Common Market and were so-called because their cargoes were covered by T-Forms rather than TIR carnets – or foreigners, mainly Turks. Over breakfast, Ossie asked if we wanted to run together to Belgrade. As we had to pick up my Czech visa in Bonn we regretfully said no. It was always good to run with a mate like Ossie; he was solid, considerate, no hassle.

It was raining hard when we rolled off the ferry in Zeebrugge. We handed in our TIR carnet to Belgian customs, had it stamped and the second volet lifted, all in a matter of ten minutes. We stopped at the Total service station a mile from the docks, where Graham debated long and hard about whether to buy a twenty-four-volt fridge which was small enough to fit on the engine cowling inside the cab. It took about an hour for the sensation of thirst brought on by desert heat to win over cool reason and then, purchase made, we carried the trophy back to the patiently waiting Old Girl and installed it between the two seats. We now had a 150-mile drive to the West German border, where we would collect the next series of stamps in our TIR carnet.

It rained all day as we drove along the Belgian motorway, by-passing Brussels, then Liège, and crossing the Ardennes near to Aachen, one of Germany’s oldest cities. Leon Ashworth, Whittle’s operations manager in Preston, had given us the broad outline of our routing, leaving Graham to fill in the details.

‘Don’t transit Kuwait,’ he said. ‘Too risky round Basra. You must enter Saudi through Ar’ar, and come back Jordan–Syria. I’ve alerted our agent in Ar’ar to be on the look-out for you.’

‘Ar’ar,’ Graham repeated, like he was trying to fit his teeth around the word and chew it. ‘’Ow do I get there?’

Leon did a double take, looking pointedly at Graham for a moment, till he realized that Blackpool’s star long-distance driver was having him on.

‘Out the gates, down to the end of the road, then turn right at the traffic lights. You’ll have no trouble finding it,’ Leon said.

No trouble at all, I thought. That was a fine one. Leon winked at Pam Aspden, his assistant. She was usually the one who had to contend with Graham’s special brand of humour.

‘Ah, aye, he’s a hard one, that Leon,’ Graham later said. ‘But when you get back from a trip, he always has the cheque waiting for you, right on his desk. That counts a lot in this game. Not all of ’em are like that.’

King Leon, the other drivers called him. But at least they felt they had a rapport with Leon Ashworth; they could talk to him, whereas they could not talk with Michael Whittle, the group’s chairman. Michael Whittle’s grandfather, Joseph, had founded the business in 1880. The Whittle firm in those days hired teamsters who drove the freight to and from the railyards and docks in wooden wagons called sling-vans drawn by draught horses that were stabled at Bolton, off the old A6 road from Preston to Manchester. ‘Our motto is “Keep moving”,’ Joseph Whittle used to tell staff and clients. And for more than one hundred years the Whittle family has been doing just that.

Graham and I were well into the routine of boredom by now. The 280-horsepower motor was humming monotonously, one of the three giant windscreen wipers occasionally sticking on its backward swing, thereby confusing the others, and water was spraying out from the ruts under our wheels in fifteen-foot jets onto either side of the roadway. The rain-soaked countryside had sufficiently deadened my visual curiosity to allow my imagination to play with a notion that international trade was a delicate mosaic of which we were now a sub-atomic particle.

Aachen, I remembered, had its place in that mosaic. Almost forgotten by modern travellers, it nestles in the Eifel Mountains, still a textile city but removed from the major trade routes. Even our route, the E5 autobahn, steered well to the south and east of it. But for almost one hundred years, beginning in the eighth century, Aachen was the capital of Europe. Charlemagne had installed his court there in a remarkable Roman-looking palace and made it a focal point of international trade. He exchanged embassies with Harun-al-Rashid, the great Arab ruler of Baghdad, and with the emperor of eastern Byzantium. For a brief few decades trade again flourished on a scale that had not been seen in Europe since the days of Augustus. Aachen remained at the centre of European trade until two tiny pieces of the mosaic changed, contributing to the collapse of Carolingian society.

The Carolingian monarchs earned most of their revenues from taxes levied on Flemish wool. Bruges was the capital of Flanders, and Zeebrugge, where the Continental part of our journey began, became its port after the North Sea inlet leading to Bruges had silted up. Flemish woollens were at the time considered the finest in the world. They were exported as far afield as Baghdad and Bokhara.

After Charlemagne’s death, the empire became burdened by internal strife. To keep the royal finances afloat, Charlemagne’s successors increased the wool tax until the Flemish merchants could no longer compete in world markets. Trade shrunk and revenues declined. Finally the empire split into three. Its break-up seemed proof that nations, like corporations, can live beyond their means for as long as their savings last or for as long as they can borrow the savings of others. But in Charlemagne’s time, as in Roman times, international lending had not been invented and so nations that lived in chronic deficit were doomed to collapse.

The Flemish wool merchants had more resilience than Carolingian monarchs. Aachen withered to insignificance while Bruges rose to become one of Europe’s great entrepôts of trade, and, together with Florence, remained a flourishing textile centre for hundreds of years.

Another factor that sealed the fate of the Carolingians was the rise of the Northmen. By then these Scandinavian warriors and traders had expanded their dominions into Muscovite Russia. From there they carried their commerce down the great rivers of central Russia to the gates of Constantinople and Baghdad, at the time the two wealthiest cities in the world and therefore the largest marketplaces for north European goods. Among the articles these ‘Russ’ traders brought with them were Baltic amber, brocade, furs, Frankish swords, and slaves. Flemish merchants began using the Northmen as their middlemen in trade with southern Europe and the East.

The mosaic was ever-changing – a living mechanism as complex as life itself. Major trends often evolved slowly and were at the time impossible to discern. As the Northmen ferried their furs and textiles south, traffic on the great caravan routes from the east was disrupted. These routes had been the bloodline of international trade, bringing silk, spices, perfumes, and other luxury items to the Mediterranean and taking precious metals, glassware, objets d’art, alabaster, Flemish cloth and Byzantine wares back to the east. But in the turmoil of the Dark Ages, traffic along the overland caravan routes virtually ceased. Muslim rulers who succeeded Harun-al-Rashid tried to monopolize the east-west caravan traffic and charged exorbitantly to match their monopoly. This did not sit well with the Norman and other Christian princes.

At this point, virtually all overland trade from the East was diverted to sea routes. Maritime shipping was less costly, and ships could handle bulkier cargoes than the two-humped Bactrian camel. But again events changed the mosaic. In 1291 the Pope forbade Christians to trade with Egypt, through whose ports the Ceylon and Malabar coast traffic passed, and about the same time the Egyptian sultan began to look upon the Red Sea as his private preserve.

Trade with the East was all but stifled. Goods still got through, mainly in the hands of Jewish and Levantine merchants who were not bound by Papal bulls nor adverse to dealing with Arabs, but it was on a restricted scale. The mosaic remained more or less unchanged for another hundred years, until the magnetic needle revolutionized navigation and made the longer sea routes around Africa into the Atlantic a viable alternative. Long-distance maritime transport, however, required greater investment for the building of sturdier vessels and larger port facilities. Merchants overcame these problems by pooling their capital to operate shipping fleets, and governments raised customs and excise duties to build new sea terminals. But whenever trade outstripped investment, overland transport filled the gap.

This was most recently demonstrated in the 1970s, when Middle Eastern ports became too congested or simply were not equipped to handle the increased trade brought on by a quadrupling of world oil prices. Overland routes again became predominant. The modern caravans were the forty-ton juggernauts such as Graham’s Old Girl. They were relatively cheap to run and didn’t require a large capital investment. One juggernaut could carry as much cargo in terms of weight as fifty camels. These forty-tonners, using extendable lowloader trailers, can transport steel girders and machine presses, or with forty-foot fridges chilled pharmaceuticals, temperature-controlled computers and frozen foods. Of course some trucking enterprises did less well than others; their rates were undercut by better-placed competitors, and traffic patterns changed. This, too, was part of the mosaic.

We reached the outskirts of Bonn around 8 p.m. that first Monday and parked off the autobahn in a small village square. Next morning I took a taxi to the Czech embassy, got my visa, and we were under way by 10 a.m., destination Prague. Graham preferred the Czech-Hungary route to Austria because there were no road taxes to pay. Austria was the most expensive country in Europe to transit – a tax of £105 for 300 miles.

It was still raining when we left the outskirts of Bonn on the A61 to Koblenz and Heidelberg. Towards the Hockenheim-Ring exit we noticed that two trucks had telescoped together in a lay-by on the right side of the autobahn. The first truck had overturned and it looked like a car was pinned underneath it; of the other, only a portion of its cab remained visible. Because of the rain, everything was blurred. Once past, something familiar about the front truck struck us, and Graham, who was on that side, as Old Girl had right-hand drive, tried to look back, but it was too late. When you have twenty-three tons behind you, you don’t stop on a penny.

‘Wasn’t that Ossie’s Transcon lying on its side?’ he asked.

I had thought the same but, as I hadn’t seen clearly either, I wasn’t sure.

‘Damn,’ Graham mumbled. We kept steaming into the rain. His mood was as grim as the weather.

We stopped at a services area for lunch of Lancashire black pudding butties and a pot of tea. While eating, Graham disconnected the CB radio and hid it at the back of the overhead rack. It was illegal to use CBs in Czechoslovakia and to be caught operating one would risk all sorts of unpleasantness which we didn’t need.

After the town of Walldorf we swung east towards Nuremberg and Amberg, which for us was the end of the autobahn. The rain had become intermittent, but was still heavy at times, as we wound through the Bavarian hills. Graham was attempting to make up the few hours we had lost that morning while obtaining my visa. Realizing a long and arduous road lay ahead, I was for taking it easy. But Graham had the overhead of his truck and an impatient bank manager to consider.

By mid afternoon we had heard the same news report a dozen times about the seventeen people killed and 112 buildings destroyed by an earthquake in Greece. Its epicentre was at the extreme southern end of the Peloponnesus, far from where we were headed. Between the newscasts, it seemed like the American Armed Forces network was playing only cowboy music that Tuesday and it was starting to wear on our nerves. Whenever the miles start dragging and time gets heavy, drivers invariably think of the women they have left behind. I suppose it’s the same with soldiers and sailors. But I knew Graham was worrying about Madeleine and how she would cope in his absence. Would he telephone her from a roadside callbox to find out? Never, not Graham. He would only call her when he was back on Dover docks in order to let her know he had returned safely.

Above the windscreen, running the length of the cab’s interior, was a shelf about ten inches deep with six inches of space between it and the ceiling. On the driver’s side Graham had installed a new touch-selector radio and self-reversing cassette deck acquired from a Blackpool discount house. The speakers were wedged into each corner of the shelf – one over my left ear and the other over Graham’s right ear. He was proud of the system’s stereo effect and so that he might enjoy the full benefit of it over the rumble of the motor he turned the balance hard left. This meant that I received a jolting number of decibels while Graham was lost in musical memories – Lonnie Donegan, Petula Clark, Buddy Holly, the Spinners, Dinah Shore and the Kinks.

As the miles clicked by, Graham would forget to change the cassette so that his favourites of the sixties would keep repeating themselves ad infinitum. My only defence was to put on earphones and turn on my Walkman. Listening to a competing cassette, but at lower decibels, I would try to read or just day-dream. Graham would finally wonder what I was up to, look over at me, and at first register no reaction. After a few minutes he might start singing out of tune with the music. At last he would ask a question – any question – just to get my attention. He didn’t like Walkmen.

‘They’re anti-social,’ he once complained.

‘What did you say?’ I was being unkind; I had heard perfectly well.

‘Those things are anti-social….’

‘I can’t hear you.’

That would get him mad. Finally he would turn the sound system down and begin again.

Other items on that shelf included the CB radio, rolls of paper towels and toilet paper. On my side I tried to wedge in a few books: a Cadogan guide to Turkey, Layard’s Nineveh and Babylon and Colin Thubron’s Mirror to Damascus among them. There wasn’t much foot room because a blue gas bottle for the cooker was on the floor, together with a ten-gallon container of motor oil. A tool box that wouldn’t shut was down on the left side of the seat. I could rest my right arm on the fridge, but had to keep on adjusting the cooker in front of it, which vibrated back and forth. Sometimes the cooker slid off the cowling, causing much confusion as it usually happened on a turn. Its lid rattled so annoyingly that we had to jam the atlas of road maps under it. At all times we had to ensure that we had turned off the gas. Once we forgot. When we realized the cock was open there was enough propane floating around the cab to blow both of us through the windscreen had Graham decided to light a cigarette.

I had a list of things to do that I knew were helpful, and tried to remember them, like wiping the left wing mirror clean of mist or rain, making sure it was properly adjusted, or that I didn’t obstruct Graham’s view of it. And above all not to kick the fuse box in front of me with my cramped feet.

Then, without warning, bang! Startled, Graham jumped in his seat. My heart skipped a beat. My books had fallen from the overhead shelf. Sheepishly, I replaced them, working hard to fix them securely back in place.

The second time they came down, Graham got mad. ‘You’re going to make me have an accident with those bloody things.’ He couldn’t understand why I had so many books anyway. What did I need them for? ‘Stick ’em behind,’ he suggested.

But behind, on the lower bunk, there was hardly a spare inch of space. The food and motor parts were stored there; on the top bunk there was my rucksack, bedroll and Graham’s battered suitcase. Occasionally these items ended up in our laps as well. If the road surface suddenly became corrugated you literally had your hands full.

Graham complained unceasingly about my large amount of gear which embarrassed even me. He also complained about the flies, the weather, and above all about my ability, in those cramped conditions, to lose things. He could be a tyrant if ever I took him seriously. But most of the time I sensed he didn’t mean it. He was only testing me, trying to provoke a reaction. It was a game that I learned to play with him. It gave us something to do. He would be amused by my lapses into alleged Americanisms. If I ever made the mistake of telling him ‘I’m off to the bathroom,’ he would start to laugh. ‘The baathroom,’ he would retort, stretching the ‘a’. ‘That’s American. What’s the matter with the toilet?’

‘But you refer to Old Girl as a truck. Surely that’s American?’

‘You can also call her an artic.’ Artic was short for articulated vehicle, I learned.

‘But not a lorry?’ I asked.

‘No, she’s not a lorry.’

I was confused. Another driver we met tried to clarify it for me. ‘Anything that goes abroad is a truck. If it stays at home it’s a lorry.’ I became even more confused.

What really pleased him was when I dusted the dashboard and helped clean the cab, or washed the tea mugs, frying pan and our other utensils. ‘My mate’s doing the house cleaning,’ he beamed, picking at a scab on his forearm.

After topping the motor up with oil, blowing diesel through into the running tanks or other hand-soiling chores, he would clean himself with detergent applied to an old rag he kept behind the seat and more often than not neglect to rinse off the detergent. I was sure the raw detergent was giving him that sore on his forearm.

Graham turned taciturn again. I looked out at the trees. Hidden in the forest on either side of us were the gun emplacements and observation posts from which NATO and Warsaw Pact forces eyed each other. Separating the two was an electrified wire-mesh fence built by the East Europeans to prevent their citizens from fleeing to the West. The fence was not far away – off to our right – but in the dark we couldn’t see it. From the Baltic it runs at least to the Danube and maybe even further, though I have never seen sign of it beyond the hills around Bratislava. I know for sure it doesn’t exist along the Hungarian–Yugoslav border. In the sector through which we were presently driving it was guarded by Czech soldiers carrying Kalashnikov rifles, and they meant business. They scrutinize every inch of the truck as you drive across no man’s land from Furth-im-wald to Folmava and if they turn even mildly suspicious they can keep you immobilized in the Folmava customs corn pound for hours.

Curiously, a little while back we had passed a large floodlit furniture supermarket in the middle of nowhere. I wondered it it had been placed there and lit up like a Christmas tree to remind the Czechs that over here it was consumer heaven, the land of plenty, while over there it was drabsville.

Counting the two rest stops, Graham had been driving for ten hours and he was getting pretty cranky. You could see his eyes were heavy and he was chain-smoking. I estimated up to sixty cigarettes a day. He lit another as we rolled up to the West German customs post. For some reason the border crossing point was in darkness. Rising out of the east an almost full moon, partially shielded by clouds, filtered silver light onto the eight trucks lined up ahead of us: mostly Turks, but I could see one Romanian and a single Brit, so we were not alone. We parked, collected our documents and took them to the customs post. Besides the TIR carnet, at each border crossing we were required to produce seven different sets of papers – our bill of lading, a consignment note known as a CMR,* the truck registration, the carnets de passage, also known as triptychs, which ensure that both truck and trailer can be temporarily imported into a country, third-party insurance papers, and, of course, our passports.

It took twenty minutes to clear West German customs and one hour and twenty minutes to get through the Czech side of the border. While still on the German side, we had a drink and a bite to eat with John Hodges, who was on his way to Istanbul with a load of diesel engines. John was taking it easy. He had parked for the night and planned to cross into Czechoslovakia in the morning. He wanted to get to the Hotel Wien, on the outskirts of Budapest, by the following night. Hotel Wien is a noted knocking shop favoured by British truckers because of the high-class hookers who hang out there. There was another motel-cum-brothel down the road from Folmava, at Rockycany, but the Brits don’t go there any more because the Turks have taken it over.

‘You just wait and see,’ John said. ‘There’ll be so many awbies parked up there you won’t be able to get near the place. I stay clear of Rockycany now, I tell you I do. Don’t want no AIDS or anything like that.’

Hodges was in his late thirties. He started as a Middle East driver in 1973, but now only went as far as Turkey. ‘I’ve had enough of the Middle East. The hassle’s not worth it,’ he said, expressing a view that was increasingly common among British drivers. He had a broad Essex accent. His sister, a quiet-spoken blonde with the looks of a fashion model, owned a stylish boutique called Special Occasions on the High Street of Kelvedon in Essex, forty-five miles east of London. Housed in an eighteenth-century corner cottage, the shop sold £500 Pierre Cardin ensembles, slinky lingerie and knee garters to the yuppie wives and mistresses from the stockbroker belt centred on nearby Coggeshall, a village which has had more than its share of society murders. A flat over the shop was John’s garçonnier when he was not on the road.

By 11.30 p.m. we were rolling again, this time in another world, almost another century: the narrow roads were built in the 1930s for lighter traffic, the villages were poorly lit and the streets were nearly empty. On the outskirts of Pilzen we were stopped at two different police roadblocks. They examined our passports, then waved us on.

‘Something’s happening. Must be looking for someone,’ Graham said. Two weeks before the Czech secret police had arrested seven leaders of the Jazz Section, an unauthorized group that was dissatisfied with state-controlled culture. It was another clear sign that the Helsinki Charter of Human Rights was not about to be implemented in Czechoslovakia, even though the Czech government was one of the charter signatories. But nobody imagined that the hardline government of Gustav Husak was about to adopt more liberal policies, especially not John Hodges, who at that very moment was seated in his cab, watching an eerie light show as Czech troops chased through the forest, which they floodlit by sectors, trying to locate a car and its passengers who were attempting to flee to the West.

‘It was really strange. All those soldiers crashing through the woods looking for a carload of obviously misguided citizens wanting to leg it to freedom,’ was how John described it when we met him again in Belgrade.

The Skoda works looked like something out of Kafka. They were darkened and idle, their overhead hopper lines and cranes but silent shadows when we passed them before the right-hand dip into the centre of Pilzen. We drove through the city on damp cobblestones and turned right again on the road to Prague, under a bridge with suspended tramway lines overhead. The sign said 3.80 metres clearance which gave us only four inches headroom, assuming this took into account the tramway cables. I had visions of the truck tearing out a whole section of the cables, bringing darkness and chaos to our lives and half the city of Pilzen.

‘She’s always passed before. Don’t see why she won’t tonight,’ Graham commented drily. The roads were greasy. Going up the incline out of Pilsen, Old Girl slipped on the cobbles, her back wheels spinning. Two more police checks, then straight road and more rain.

About 1 a.m. we rolled into the lay-by at Rockycany. Just as John Hodges had predicted, scores of Turkish trucks were jammed into the parking lot outside the motel. ‘These bloody Turks,’ Graham grumped. ‘As soon as they get onto something, they spoil it, don’t they?’

We had stopped because our running tanks were empty and we needed to blow some diesel through from the belly tank. First Graham broke the customs seal on the belly-tank spigot. Then he ran a length of hose from the spigot to the running tanks. Next, he disconnected the brake-line-airhose and coupled it onto a nozzle which fed into the belly tank. Finally, he opened the spigot and used the air compressor for the brakes to build up enough air pressure in the belly tank to move the diesel forward into the running tanks. Simple.

While Graham was supervising this operation, a Turk stumbled out of the motel and lurched towards us. East European police are severe about drinking and driving. If they find a truck driver has even the slightest trace of alcohol in his blood they not only confiscate his licence but see to it that he is banned for life from driving in East-bloc countries.

‘Eh, Kollege, hast Du die Polizeikontrolle weiter oben auf der Strasse gesehen?’ the Turk asked in good but halting German. His truck was facing west, towards Furth-im-Wald.

‘A forest of them,’ I told him.

He grunted and turned back to his truck. ‘Besser dass ich schlafen gehe,’ he said.

‘Ja, dass ist eine seehr gute Idee,’ I remarked.

We set out again into the night. Crossing the road ahead of us were two fawns and a buck. They stopped and blinked, then disappeared over the hedge. Finally, after skirting Prague on the new by-pass and climbing the hill to the main Prague-Bratislava motorway, we arrived at a services area and parked for the night. It was 2.20 a.m., and Graham could no longer keep his eyes open.

* CMR stands for Convention relative au contrat de transport international de marchandises par route, the so-called CMR convention. A CMR consignment note confirms the contract of carriage and is made out in three original copies signed by the sender and carrier. The first copy remains with the sender, the second accompanies the goods, and the third is retained by the carrier.

CHAPTER THREE

Driving with the Devil

NORTH of Brno, in the Czechoslovakian hills, we saw our first rays of sunshine in three days. We were steaming along the motorway, soon to take the detour for heavy vehicles over the mountain behind Bratislava, a bit of roadway that all drivers hate.

Pulling around a sweeping left-handed bend on top of the mountain, we spotted two British trucks on the lay-by and pulled in. It was 2 p.m. and time for lunch anyway. Our two mates were Bob Hedley, an owner-driver pulling for Astran, on his way back from Muscat at the extreme eastern tip of the Arabian peninsula, and Gordon Durno, driving for Falcongate. Gordon was taking a load of spare parts to Athens.

Hedley had been on the road for seven weeks, and had only £20 left in his pocket. Durno, a kindly Scot in his mid-fifties who once did only Middle East work, had just given Hedley enough diesel from his belly tank to get him back to Dover.

Hedley had been delayed at Kafji, on the Saudi frontier with Kuwait, on his outward journey because as he arrived there the customs administration closed for four days to celebrate the Muslim New Year. When the holiday ended, the Saudis announced that a new decree had gone into effect on the first day of the new calendar limiting all trucks entering the country to one diesel tank only. This cost him another two days of pleading with the customs manager not to remove his belly tank. As Hedley was transiting Saudi for Muscat, the customs manager relented and did not molest the truck more than to cut open the diesel tanks to peer inside for contraband. ‘But that’s it, mate. No more belly tanks. They burn the fuckin’ things right off with a fuckin’ blow torch,’ Hedley said.

‘Bloody hell,’ said Graham, ‘I can’t let them do that.’

‘You won’t have no choice. They’re raving maniacs down there.’

Hedley, who weighed seventeen stone and was known as The Animal, was one of the original Middle East drivers. He had been on the run for almost as long as Dick Snow, a former Royal Navy radio operator who also drove for Astran. Snow, at fifty-two, was regarded as the dean of British long-distance truckers. He made his first trip down the line twenty years before when Astran ran not only to Kabul but crossed the Khyber Pass to places like Rawalpindi and Lahore. Because of the seven-year-long civil war in Afghanistan and problems with the Iranians, that kind of driving had ended, at least for the moment.

Hedley’s red and black Ford Transcon looked like it might have just come over the Khyber and had taken such a pounding that it needed to be Scotch-taped together. Bob’s clothes were covered in grease, and he was unshaven, but he was smiling.

‘Two drivers?’ he said, looking at me. ‘Which route you going?’

‘Ar’ar,’ I said.

‘They won’t be having that, either. Two drivers aren’t allowed in Saudi. One of you’ll have to stay behind.’

Graham looked at me, and I at him, wondering whether to laugh or cry.

‘Well, if they only allow one of us through, we know who it’s going to be, don’t we?’ he said.

‘Oh, I don’t mind taking Old Girl to Al Khobar on my own,’ I replied.

Graham was not in a mood for jokes.

While Gordon was shutting the valve on his belly tank and storing the hose, we asked Hedley if he had seen Ossie MacIntosh anywhere along the line. We were hoping someone might have passed him. Hedley had not. It was still conceivable, however, that Ossie and Hedley had taken different routes. Nevertheless we feared the worst for Ossie and it did nothing to brighten Graham’s mood.

‘Bob’s a walking disaster. I dunno how that man keeps driving,’ Gordon said after Hedley left us.

We sat and talked for a while, building cheese-and-onion butties. Gordon was going through Budapest to see what he could find and was in no hurry. He was on salary; Graham was not. Graham wanted to take a more direct route, across the Hungarian meadowlands to the Yugo frontier near Subotica, and then on to Belgrade. After leaving Gordon, we descended into the Danubian plain, heading for Medvedov. The corn was being harvested in the warm September sun and the fields were broad and flat, with dark, loamy soil. The roadsides were lined with cherry and chestnut trees and children were busy picking the chestnuts. The farmers here seemed more prosperous than those in the north of the country. Their cottages had well-kept gardens and the lawns around them were carefully groomed. Some had little castles and brightly-painted gnomes standing in the grass.

In spite of the light traffic, at Medvedov we found two dozen trucks in front of us, waiting to get into the compound shared by both the Czech and Hungarian customs services. Entering the compounds, we rolled over our first weighbridge, slowly, slowly so as not to disrupt the scales. No other country on the Middle East run is as strict as Hungary on axle weights. The maximum gross weight for five-axled articulated vehicles is the same as in the United Kingdom – thirty-eight tons. But the maximum allowed on any one axle is eight tons. Should the weighbridge show nine tons, the overweight fine would be one Deutschmark for every excess kilogram, or the equivalent of £260. Nobody came out of the weighbridge house to challenge us, confirming that we were within the limit on all axles. If, however, a problem had existed, chances are it could have been solved with a backhander, though the profferer must be very careful. Everyone in the Eastern bloc likes their own cache of hard currency, and the Hungarians are no exception.

A Czech customs officer collected our passports. Three hours later a Hungarian customs officer returned them. Finally, at 8.15 p.m., we left the compound and headed for Györ, only ten minutes away.

‘Don’t you find you get a good idea of a country’s character during the first few miles on its roads?’ I asked Graham.

‘Oh, aye, sometimes the difference from one country to another can be like night and day, though only a line on the map separates the two.’

The change between Czechoslovakia and Hungary was immediately noticeable. We could see that Hungarian roads were better maintained; homes and factories had a more prosperous air; even the car and truck parks were filled with new vehicles, a fair percentage of them imported from the West or Japan. The streets of Györ were wide, well lit, well marked, and above all spotlessly clean. Life, also, seemed to move at a faster pace.

Györ is on the right bank of the Danube, where the Raba River flows into it, and the Raba’s name has been given to the city’s major truck works as well as to an immense new sports stadium. The emperor Augustus was the first to bring an organized army through the town which, because it sits astride a well-trodden passage, has been burnt and rebuilt many times. In the older sections, many fine baroque and rococo houses still exist, though we saw none, skirting the city’s industrial suburbs.

‘It’s just like Switzerland,’ I remarked.

Graham said he didn’t know whether it was or not, as Switzerland was one of the few countries he had never motored through. But the faster pace on the better surfaced roads interested him. He was hoping to make up the time lost at border, not by pushing Old Girl faster than the 40 mph limit (50 mph on motorways), but by extending her hours on the road. This can be done in East Europe, Turkey, and the Middle East, where no limit on driving hours is imposed. In the Common Market, however, truckers are not supposed to drive more than nine hours a day, with rest stops required at specified intervals.

We cut through the heart of Hungary in the middle of the night. There was a full moon rising, and some ground mist in the valleys. Graham was pushing Old Girl through corners, down hills, and into the foggy hollows, my cassette of Beethoven’s Second Symphony blaring from the roof speakers. Where normally we might have slowed for a bend to, say, 30 mph, Graham held her at 40 mph. Old Girl rattled, her brakes hissed, and the gears grumbled as he moved them up and down the ten-speed box, and sometimes they jumped into neutral of their own accord. We felt like a train and the engineer was driving her as if the devil himself was sitting in the caboose. We had hoped to reach Belgrade by midnight, but our late start from Prague and the delay at the Hungarian frontier had excluded any possibility of that.

‘We’re a funny lot,’ Graham finally said, looking over to see if I was listening. He had lit another cigarette and the glow from it reflected off his glasses like snake eyes in the night. ‘We’re a breed unto our own, really. We have to look after ourselves. Nobody else does. Once out of the Common Market we’ve got to drive sixteen hours a day to make the job pay.’

Graham started explaining his driving philosophy which included a lesson in road economics. ‘Put it this way,’ he continued. ‘I’ve got to clear £2,300 this trip. That means I’ve got to do it in five weeks. If I don’t, I start losing £500 a week.

‘It’s a game, you know, where it’s all go. You haven’t got a moment to live. And it’s all about money. Certainly no pleasure job. But it gets into your blood, and once it does you can’t get it out.’

Ivor Graham Davies was born in the village of Biddulph, in Cheshire, on 22 November, 1936. He was the eldest of three boys. His father, Garnet Davies, was a motor engineer who had a garage at Stoke-on-Trent, in the Potteries, where Doulton and Wedgwood china are made. In 1948, his father sold the garage and moved the family to Blackpool, where he bought a rooming house. But the tourist trade didn’t appeal to him and after a few years he sold it and became a foreman at Platt’s Engineering Company in Blackpool.