Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

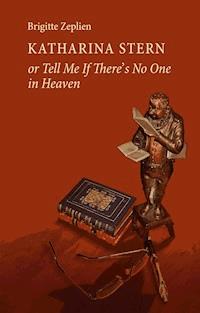

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Rostock, Germany, 1996. Katharina Stern, a busy school principal at a rural school in the former German Democratic Republic, finds herself reevaluating the past and life itself when her son suffers a mysterious collapse. As her family slowly comes to terms with Felix's brain tumor, Katharina recalls the days of living in 'the Golden Cage' of the GDR, the events that triggered her dawning realization that not all was as idyllic as it seemed to be, and the sudden, harsh changes that took place when the Berlin Wall fell. This is a deeply personal and philosophical look at the history of East Germany, and the meaning of personal freedom and our own ideals. An exciting and touching novel about life’s irritations here and now, which stimulates the reader’s inner reflection

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is loosely based on historical events that transpired fifty years ago. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. Real places and historical figures are depicted under artistic license.

Table of Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Epilogue

PROLOGUE

Hamburg, April 2009

The young woman tore through the pulsing city’s glittering streets in a panic. She pressed on through the unfamiliar surroundings like a hunted animal, unthinking.

Jeanne Alien soaked up the evening, the city seeming to her like a bright shining star spreading the heady light of its bustling center out into the warm darkness of the outer boroughs where people lived. “Like a star,” she thought. “Can I really find heaven here – after escaping from hell?” She felt the first tiny seeds of love for the city start to bloom inside her. Hamburg was a lot like her beloved Montreal in Canada, where her parents lived. It seemed as though the cool spring evening wanted to tuck a blanket over the secrets that slumbered deep within the city.

The attractive young woman cut a sleek figure. Her blue-black chin-length hair was smoothed expertly in an expensive haircut, in perfect keeping with the style of the day. Her slender hands looked elegant with a salon manicure, tiny patterns on the tips. Yet her anxious gaze and fluttering hands did not match the perfectly groomed eyebrows that accentuated her dark eyes. Nor did she quite fit the smoothly tanned skin that should have maintained the facade of beauty.

The small suitcase hadn’t held much.

“I really only need clothes and a pair of underwear,” she concluded silently, and went into a brightly-lit shopping mall, where she was immediately greeted by glowing backlit ads and enormous mirrors in the entryway. She deliberately walked slowly over to them so she could casually check her reflection. There were the first greying roots glinting distinctly out from under the black. “I really ought to get those dyed. Preferably right here somewhere.” She looked around uncertainly. Who could she ask? Everyone was speaking a language she didn’t know, but they’d understand her English. The nearest hairstylist was right around the corner; she was, after all, in the most expensive mall in Hamburg. “Credit card?” Kreditkarten? Natürlich. Of course. Here, at last, she was in a city of the world. The international scene was all around her. Not just the hairstylist, but every single store offered unlimited possibilities. Hamburg, the home of her company’s headquarters, welcomed her with open arms.

She would never go back to that backwater town in Italy, to that awful family of her Italian husband’s! In a mad rush, she’d fled and gotten the very first train to Hamburg. She would ask if she could be transferred from the Italian branch to work here.

She also needed a place to stay. A woman on the internet had offered a furnished room for 995 Euros a month. It did not occur to her how much that would add up to. She went straight there, though she had no idea where she was going to get the money from.

“No matter. It’s better than nothing. I’ve got another credit card anyway. And Maman will support me.” Her credit card did the trick, even though she hadn’t been in good standing in ages. Far away, Maman was tearing her hair out.

“She and her husband were so happy when they were a young couple studying in Montreal!” thought Maman. “But all those years playing the traditional housewife with that Italian family made my little girl’s life a living hell.”

Jeanne ran away several times during her eight years of marriage there, though she had learned to love the Italian language.

“That awful family haunts me in my dreams,” she told a friend over the phone. “They make me cook and make them Italian food. My husband took my credit card, suspended my account, and started rationing my money out to me. That was the worst. It was so degrading. We owned a really nice expensive condo. But all my income was going just to that, paying for the interest and mortgage, with nothing left for me.”

She spent six months in Japan – everything was fine there! When she had to come back, hell broke loose inside of her. She was miserable, even more so with alcohol.

“You can’t go on like this,” her mother-in-law scolded her. She ended up in the hospital with severe alcohol poisoning. Her life was on the line. If she had never woken up again, only her mother in faraway Canada would have wept.

Maman kept coming to visit for several months (even over Christmas, while her father stayed home due to his fear of flying) to counsel her only daughter, to look after her and even cook for her a bit. Normally Jeanne always went to restaurants, because she hated cooking.

Maman admitted that she spoiled her daughter, but she herself was already past her mid-thirties when she had had Jeanne, and she loved her only child. “Why did she have to move so far away from us?”

Her in-laws berated her mother when she stayed on for months, insisting that she pay for her own groceries. Jeanne’s outrage at this knew no bounds.

She couldn’t sleep at all anymore, she worked at her computer through the night, sought refuge yet again in training programs, new degree programs, language courses. Foreign languages, foreign countries – she lapped it all up like mother’s milk. Learning represented the one activity that she could perform to her satisfaction.

Her mother paid up, setting aside money from her tiny pension.

She made phone calls every day between Italy and Canada. Without her mother she was incapable of dealing with life, incapable of dealing with conflict. She couldn’t handle all the difficulties piled up in her life by herself. So she fled for the third time, this time to Hamburg, with a handful of antidepressants, sleeping pills, and painkillers in her bag.

She stared contemplatively at her reflection, lost in the middle of the throng of people in the huge shopping center.

All her wits screamed for an immediate divorce, but Italian law worked differently from Canadian; three years’ separation was required, she knew that much. Unbearably long. The Italian family would never pay out any money to her.

“It’s hopeless,” she whispered to herself, in tears. “I don’t want to any more. I give up.” She lingered there, standing in front of the racks full of bottles with luridly colored labels.

“Hello, Jeanne Alien, where did you come from?” The friendly English greeting yanked her back out of the muddle of memories and perilous ideas swimming through her head. “We’ve met before!”

She could only muster up a vague memory of some company party last year. “When? Who are you?”

The young man had an open, cheerful air about him. “Do you need any help?”

His English saved her from being completely stranded in this German city. Meanwhile though, her own talent for languages bordered on genius. With Maman she spoke French and Spanish, English with her dad, Italian with her husband. She’d only need a few months in Germany to learn the language, just as she had mastered spoken Japanese after only six months there. Her genius hovered just shy of the line bordering madness.

Did she need underwear? He could go with her to pick some out; she was, after all, wandering around a completely foreign place and needed some help. Any sense of inhibition appeared not to bother him. He’d be happy to accompany her, seeing as how she seemed so lost. Readiness to help was his calling card.

The young man -- who introduced himself as “Felix Stern, like a star” -- had an easy light-heartedness about him that put a stop to her melancholy. He beamed at her like his own namesake, like a sign from heaven. It seemed someone up there didn’t want her just yet.

CHAPTER 1

I’m Seventeen-thirsty.” year-old Felix sat waiting restlessly on a bench down in the shopping center’s entryway. He’d met his mother here after school to help carry her shopping. He was looking rather pale.

“Did gym class make you sweat that much today?” Felix said nothing.

“Can we quick stop at the shoe department first, before we get something to drink?” Katharina was, as always, in a hurry.

Felix nodded mutely. He appeared not to have the strength to push his request for a drink. His mother noticed nothing. Together they pressed on through the crowd, who, like her, apparently also scrounged around the mall after work. The fragrant aroma of the perfume department wafted over to Katharina, luring her in. It would just be a quick detour on the way to the shoes. She didn’t come here that often. The family lived in the country on the edge of Rostock, and her visits into the city center usually involved more than just one purchase. Katharina was always finding more things to decorate the house with, or little presents for family and friends. She hadn’t broken that habit from the time before the reunification: always on the lookout for nice things, even if she didn’t need them right away, just to stow away for special occasions.

Suddenly Felix stopped in his tracks.

“I’m really thirsty. I can’t wait anymore.” Surprised, Katharina looked at his face. He looked unusually serious. And he looked somewhat unwell. Her maternal instincts kicked in.

“That bad? Well come on, then. Right over here across from the mall – there are drinks in that little grocery shop, too.” Felix shuffled along behind her, noticeably lagging, while she egged him on. “It’s not far, come on, we’re almost there.”

She almost felt a bit annoyed that he couldn’t wait until they got home. On the other hand, it must have been pretty urgent, considering her patient, even-tempered son let almost nothing ruffle him.

They filed into the small shop, where they were greeted by a little bell on the door. It smelled musty, like potato sacks and beverage crates and cabbage. The shop girl turned a friendly face towards her only customers and waited.

“How can I help you?”

Katharina didn’t turn to look at Felix when she asked him if he wanted apple juice or a seltzer. In that moment there was a crash behind her, like a crate of drinks had been knocked over. Felix lay on the floor, not breathing. The shop girl bolted out from behind the counter in alarm. Katharina knelt down and shook him, her eyes wide. Fear gripped her. Had it only been a few seconds, or minutes already? Her heart seemed to have stopped beating.

“Is there a phone here?” she shouted at the shop girl, who was similarly fluttering about in a total panic.

Suddenly a very weak voice, trying desperately to drown out the two excited women, whispered. “Hey, what’s wrong? I’m getting back up.”

Felix slowly came to, though he didn’t immediately understand why he was lying there. Katharina held out a bottle of water, which he sucked down greedily.

“Just stay there, we’re calling a doctor.”

“What for? I’m totally fine.” The two of them pulled him up, and he tried to move with shaky knees. “Everything’s fine. Yeah, of course I can make it to the car.” Carefully Katharina shielded her son, and walked the endless five-hundred-meter stretch to the car with him.

Later, she could not recall the thoughts that had filled her head during the short drive back to the house. An insane fear had suddenly paralyzed her.

What exactly was she supposed to make of this? What did it mean?

January passed.

An indescribable panic propelled Katharina from doctor to doctor with her young son. MRI scans of all his internal organs. No result. No doctor could find an explanation. Perhaps school was overwhelming him. Maybe it was a psychological problem?

In February they got nothing but headshakes of surprise and dismissal from internal specialists. “We’ll do an MRI scan of his head just to make sure. – There’s nothing to see there. – It’ll go away on its own.”

Spring came. The boy lost more weight; the dark circles under his eyes were becoming permanent fixtures. He needed to rest more, his graduation exams were weighing him down.

Katharina’s agitation grew.

In spite of this, she followed up an opportunity to go on a six-week educational trip to America. One of her life’s dreams suddenly had a chance of coming true. Was she supposed to stay home and take care of her son? Subconsciously she was tormented by guilt. Even in a nurturing family, no one – not a father, not an older brother, not the grandparents – could relieve her of the maternal responsibility weighing heavy on her shoulders.

Felix passed his driver’s license test while she was gone, right after his eighteenth birthday. He didn’t want to wait a single day longer. To him, cars were part of a new freedom associated with adolescence. They e-mailed each other every day of the American tour. For the first time, Katharina was trying out a completely new experience, traveling across huge distances.

“Mom, I’m doing better. Dr. Weise gave me some meds so I don’t keep having to go to the bathroom all night. That way I can get some sleep again.”

“What else did Dr. Weise say?”

“She’s got a theory, but she doesn’t want to discuss it yet.”

Katharina’s first impression after her trip was that he didn’t look better, and he had lost even more weight.

The otherwise lively boy was very quiet in his classes. He couldn’t focus anymore. An eye doctor declared his field of vision to be severely impaired. He could only see what was right in front of him. Nothing to the right, nothing to the left. Felix, spoiled by his own hitherto excellent grades, stopped concentrating on his exams. The poor results shocked his self-confidence deeply. He didn’t understand. He was exhausted. Dr. Weise, an experienced internal specialist with 40 years of professional practice, was puzzled.

“This is really very unusual. All signs point to a tumor. But I know there was nothing in the scans back in January. I don’t understand this. We’ll do another scan of the head.”

For months Katharina felt the weight of an irrepressible and immovable mental pressure. It couldn’t be a tumor wreaking havoc on his system; the Rostock doctors had ruled that out in January. Why so afraid, then? That she might lose her son? She pushed the thought away immediately. Never would she risk saying it out loud, lest the mere utterance degenerate into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Deep down inside her lurked a susceptibility to superstition.

What could she do? For him, it seemed, she could do nothing.

For herself? Long ago, as a ten-year-old, she wrote in a diary whenever she wanted to get out her worries and troubles. That helped. Every day, for ten years. Five thick volumes were born out of the worries of a young girl. Then she thought every problem in her life had been duly processed and resolved.

But now, twenty-seven years after her last diary entry full of pubertal uncertainty, she began to jot down her personal thoughts again. Writing forced her to analyze the facts and actively grapple with a situation that would otherwise doom her to helpless inactivity.

Sunday, September 1st, 1996

The last day before his operation – finally, an end to this debilitating uncertainty. They’re going to open his head. Last week we received – against all expectations – the final awful results from the MRI: brain tumor. My hand is shaking as I write these simple words. Seven centimeters in size. The doctors didn’t see it for months. Too long. A false diagnosis. Even though it should have been seen in the MRI scans back in January, Dr. Weise said. I can’t believe something like this is happening to us. A brain tumor, all along. That sounds horrible. Like a death sentence.

We still have to find out whether it’s benign or malignant. Does benign mean it’s only half as bad?

I write this not knowing, his last day before the operation, although my fear doesn’t feel any different. Meanwhile I think of how the enormous crown of our fruiting walnut tree juts out and casts the garden into shadow, so that the young plants lose the struggle for precious life-giving light. If I look out the window to the railroad embankment across, I hear the savage racket of the freight train hammering angrily along the tracks, as though it wants to take out me and my fear all in one go. In contrast, I feel so far away from the time when the kids and the walnut tree were still small and growing up in the sun in the garden, and the train to Hamburg would rush past like a ray of hope for our unspoiled world.

This morning Felix is painting the last bits of the new filling station in his father’s agriculture business.

Karl gives practical work to everyone who supposedly has nothing sensible to do. He’d never understand that the students in my school can get into mischief or even have mental problems. He thinks picking up rocks will knock the nonsense out of their heads.

Felix is noticeably happy that he’s finally made it.

From now on the couch is his again, just like every day for the past eight months.

But in the afternoon Olaf persuades him to come back to the cow barn at Daddy’s business, to help out with coating and building. He lets Olaf tell him what to do, since his brother is, after all, five years older and more mature than he is. Felix needs the distraction.

He’s barely even at home Sunday evening! He calls up all his friends, seemingly without a care in the world, and goes to meet up with them for an evening get-together. (What would he have done before the reunification, when we didn’t have a phone? In the whole area there was only one phone at the doctor’s, one in the school, and one in the co-op.)

Tomorrow morning it’s supposed to get serious.

Katharina was part of the happy post-war generation, who never personally had to witness a war.

For almost forty years of her existence she lived untroubled in a country that the later generations might remember calling the German Democratic Republic, or the GDR. There was no other name for the country besides those three letters, making it easier to later disregard the traditional name Germany, to which it no longer belonged after World War II, and moreover wanted to distance itself from Germany’s Nazi past.

She had been born only five years after this dreadful war, which, responsible for more than fifty million deaths, had come into its own as a symbol of human madness. If she’d asked questions as a child, she would have been able to learn more from the unsettling stories of her parents and grandparents, eyewitnesses with contradicting accounts. But she was still too young, and the stories with their terrible content barely grazed her consciousness. The grown-ups whispered, when they talked about it, how her grandparents, from what was then known as Liegnitz, had lost everything except for a single suitcase during the war and how the events of their escape from the East were seared horribly into them forever. The escapees recounted their unimaginable suffering often and over and over again.

So these accounts were part of Katharina’s everyday childhood in much the same way as her makeshift playground of ruins, flattened debris cleaned up from the buildings in Leipzig that had been destroyed by bombs. Where before there had stood wonderful stately rows of houses from the Gründerzeit, there were now gaping holes everywhere by their house on Alfred-Kästner-Straße. For children, these were great places to play. She thought it was lovely.

On these playgrounds Katharina collected glittering glass fragments of all colors, pretty little gems that had once been part of a magnificent chandelier. She discovered the remains of colorful toys with long since faded colors, and searched eagerly for the pieces that went together. Then she tried to reassemble the treasures she’d found, feeling like a knowledge-thirsty explorer on an excavating adventure in Ancient Egypt.

The six-year-old had a particular love for the overgrown garden behind the remains of an old wall across from their house. No one chased her away from there, because no one owned it anymore. Wild bushes grew so high out above it that one could build their own little romantic hideaway there. Undisturbed by the eyes of adults, together with the wild hordes of neighborhood children, she created a safe and peaceful kingdom out of the excavated bits and pieces of the bombed playground.

As a young pupil she went on the peace education excursions to the concentration camp at Buchenwald. Here she even stood in front of the door behind which the great Ernst Thälmann had been shot. She strolled through the actual barracks, a cheerful and unconcerned child, and looked at the pictures of mountains of withered corpses and heaps of gold dental fillings that the Soviet army had gathered after the camp’s liberation.

Very early on, Katharina was confronted with pictures and events that she simply was not capable of grasping. To her, the stories behind these pictures seemed just as inscrutable as the idea of millions of victims in World War II, which was what the speech was about. So she had long since grown accustomed to being faced with this sort of thing, and every time she nodded in understanding, but she hadn’t understood a single thing.

Given the repetitive assault on Katharina’s ignorance and innocence by the depressing memories of the adults, and the cautionary tales regarding phenomena from Fascist-era Germany, none of it really sank in anymore. Dangerous truths need only be diluted through regular repetition, the shock comes to be replaced by habit and indifference, and people stop asking unpleasant questions.

This was most apparent when it came to the war stories Katharina’s father told. The way he told it, his time spent in France as an eighteen-year-old German radio operator had been nothing but a thrilling adventure. In June 1944, when the Allies were invading and his troops withdrawing, he was wounded and taken prisoner by the Americans. Together with his friend Ernst, he managed to escape the prisoner transport and spent three weeks wandering around Germany. Following a horrific odyssey through his war-torn country, where every moment his life was in danger, he managed to reunite with his mother In Lützen, after she escaped from the East in 1946.

Katharina heard this story at nearly every party. As soon as her father had had a bit of alcohol to loosen his tongue he hogged the spotlight, appointing himself solo entertainer for the evening whether his guests liked it or not. To Katharina, his words sounded funny, but she didn’t understand what he was talking about, and she soon lost interest whenever he “talked about the war again.”

By the time she was finally old enough to understand her father’s experiences, he’d told the story so many times, using the same words over and over and over again, that she couldn’t stand to listen anymore. So her ears remained closed to the unbearable wrongs committed, and she never had to face up to the gory excesses of human ingenuity that had risen out of ordinary human minds in the name of God, the people, and freedom.

Monday, September 2nd, 1996

I still have two hours of class left. Class can never be cancelled. A teacher always brings a smiling face into the classroom. Never show weakness. Especially as a teacher. Even when I feel like I’m choking on fear.

Felix comes in our red Passat and picks me up from school. His driver’s license is still new; he took the test just a few days after his eighteenth birthday. How he did that in his condition is a mystery to me. Three months ago it would have seemed perfectly ordinary.

My father wants to drive with us to Greifswald. The anxiety for his grandchild won’t let him wait placidly at home. He’s on medication, which he absolutely needs in order to cope with the horrible depression that’s haunted him for years. I’ve learned from him that there are illnesses that can alter a person to the core. It all starts in the head.

Felix will drive by himself. It takes more than two hours of driving through the country roads of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern from Rostock to Greifswald, with tons of little places in between. There’s no fast route connecting the two university cities.

At the clinic on Sauerbruchstraße we’re waiting on Professor Nahm, the principal of neurosurgery. He has a good reputation as a specialist. I immediately have full confidence in him. I want him, the expert, to perform the operation.

“Does your private insurance cover treatment by the chief physician?” asked the secretary. My heart dropped. No idea. I had never really paid attention to the details of my insurance before. “Otherwise the operation will cost 5000 DM more, to have the chief physician do it.” I called Karl as though in a trance and counseled with Grandpa. We were in immediate agreement. Of course we would pay it, no matter what. We would figure something out.

Katharina lead the picturesque life of a woman born in the GDR. She started school at age six on World Peace Day, followed by eight years of polytechnic secondary school (or POS, as they called it), four years extended secondary school, passing the last-year exams with honors, four years earning her degree in English and German studies, with resulting qualifications of the highest possible score. Done.

“When I was twenty-two I had my teaching degree in the bag,” she happily pointed out later, in contrast to the teacher trainees on internship, who, during the course of their years-long journey through academia, often grew right past the ideal teaching age before they’d even had a chance to start.

“Done,” for Katharina, meant that at twenty-two years old she was available as a qualified teacher of English and German for all children between the ages of ten and eighteen, according to “where the state needed her.” She’d had to agree to that in writing at the start of her teacher training. Exceptions possible in case of marriage.

So she married right before her deployment was to be decided, and landed at a small POS with just one class for each grade, in Pammerow near Rostock. She felt happy; newly married, pregnant, and full of idealism and illusions of being able to make the world a better place, if one started with the children. Heaven on earth.

With casualties, she learned how to live. First she was deprived of her husband for a year and a half when he deployed with the army. Second, she lost her child at the end of the first trimester, getting a gold medal in the long jump at a teachers’ sports day. She kept her tears hidden. Through her work load, she was quickly able to numb the feeling of loneliness in this little village away from the familiar city. Her idealism and illusions would hold out for a while longer.

“You’ll take over as English and German teacher for the seventh grade with thirty-six students, as well as all the English classes for every grade in the school,” Principal Hollenkamp instructed her. “Up to now we haven’t had a qualified teacher for English. Aside from that, we still need history, music, and biology. – Do you play an instrument?”

“Yes, the accordion.”

“That’ll do. Then you’ll also take on all the music classes for grades 7 through 10.” Katharina’s breath caught. She’d heard of such unprofessional things from a colleague in the lower level, who had only started a few years before her at Pammerow. In fact, she successfully taught four grades, 1 through 4, which she had to teach all in one classroom in an old building down by the Warnow River, far removed from proper school buildings. The schools in Mecklenburg appeared to be remnants from the last vestiges of the middle ages. Though it was bewildering, she would never voice the thought out loud.

“But I never studied that at university,” she objected timidly.

“Doesn’t matter. At least you’ll recognize the notes. We haven’t had that here in ages.”

“And how am I supposed to teach history and biology properly?”

“That’s part of general education. For history you just need a class standpoint. You’ll pick it up soon enough.” And with that she was dismissed from the principal’s room.

It didn’t occur to Katharina to disagree, out of her complete trust that authority must always be right. Principal Hollenkamp enjoyed a special “expert” status in her eyes; surely he had already put some thought into his instructions. Her own upbringing as an obedient child living in this country led her to behave herself. No one ever really asked for her opinion.

She had to be thankful that, with her Saxon linguistic background, she hadn’t also been offered to teach Low German. In these parts many of the older people spoke the traditional Low German, even her Karl, but it appeared to be decreasing in the younger population.

So she sat night after night preparing music lessons as well, which took even longer than her already enormous workloads for English and German, and struggled with her class standpoint through the history of the labor movement and the anatomy of the ringworm. As the only music teacher, she took over the after-school choir as well, every Thursday at 5 pm.

Her mother, far away in Leipzig, warned her: “If you want to raise your own kids soon, you’re going to have to change your work schedule. Karl is in the army and we aren’t going to be right there to help you.”

“I know. I’ll manage on my own.”

Tuesday, September 3rd, 1996

Felix has his own phone by the bed in his room at the clinic. He doesn’t want to be alone and is calling all his friends again. He invites them to visit him in Greifswald on the weekend. Free of concern and full of optimism. Why does it again strike me, that in 1990 we only had 8.3 telephone connections for every hundred residents?

There are two young men talking in the room, who are doing surprisingly well already following their tumor operation a couple days ago. Secretly I envy both of them their freshly bandaged white heads. They’ve already got it all behind them. Maybe.

I had no idea that I’d arranged such great health insurance – we got a call back on our inquiry today. I am indeed covered for chief physician treatment. Fantastic!

Felix goes with the other two patients to walk to the nearest ice cream parlor, without getting permission to leave. Then he smirks at the commotion in the clinic like a hero returning from an adventure. Is this another effect of our newfound freedom? I never would have dared do such a thing.

When baby Olaf was born later, she didn’t change her work schedule. From the very first day, little Olaf was accustomed to going into his crib at 5 pm. The baby happily slept through the night, waking at 7 am. That saved her.

Why was it that this child radiated so much peace and contentment? Katharina amused herself with her own theory. “It’s all down to class standpoint. As early as his own complicated birth, the little one wanted everyone to know his outlook on the world. While five doctors were hovering over me with a bunch of equipment, ready to start cutting away at any moment, the little one greets the whole little world of the GDR with his tiny butt first. ‘Leck mi in Ors,’ as they say in Low German. Kiss my butt. You can’t blame him for it.”

While Katharina felt elated after making it through the birth, the radio spent the whole day playing tragic melodies on every station. Walter Ulbricht, the first secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany and chairman of the state council, had died. His hoarse Saxon voice would go down in world history – with the words that reached everyone in 1961: “Nobody has any intention of building a wall.”

Olaf didn’t disturb his mother’s time consuming schedule of school and her classes. To take care of him during the day she had found Grandma Hanschke, a 72-year-old, white-haired, friendly old woman who never took off her grey-checked apron and would happily take care of little ones for a few extra Marks to add to her slim pension. A hard life with a violent alcoholic husband made her look older than she really was. Having had no children herself, she’d raised his four children during the harsh years of and immediately following the war, in which there was often little to eat and the garden behind the house was full of provisions, vegetables, fruit and potatoes, chickens and geese.

With Grandma Hanschke little Olaf was content. She took him with her into the garden and showed him the brown-speckled baby bunnies. She went walking with him, played with him, fed him the supplied puree out of a little cup, and cleaned his cloth diapers.

These diapers were made of woven cotton Katharina had to cook in a large preserving pan, but she could never manage to get the fresh white back again. Over months, despite Katharina’s greatest efforts, they slowly turned yellow from the hard, chlorinated water, so that she didn’t dare to hang them outside on the washing line anymore. The people in town might talk. She would be ashamed. There were model housewives there, whose lives consisted solely of daily cleaning and washing, and who refused to tolerate a single speck of dust anywhere, let alone raindrops on the window pane. She hung snow-white diapers on her line. It was an example of keeping up with the unwritten laws of the town, and Katharina’s guilty conscience grew with every load of laundry.

While collecting the ingredients to make a cake for tomorrow’s birthday party, Katharina discovered that she was almost out of sugar.

“Damn it, it’s already after six, the co-op is closed by now. But I need the cake to be ready tomorrow right after school. I need to bake it tonight,” Katharina thought out loud. She was getting into a panic. Maybe Maria could help?

Katharina hurried to ring at her neighbor Maria’s, who also lived on the newly built block.

“Could you lend me some sugar?”

Maria, pleased by the unexpected company, immediately invited her in apologetically. “Katharina, you must excuse the mess in my household, I haven’t gotten around to cleaning yet today. Come in.” Katharina expected to see a slovenly, chaotic home, even though there weren’t any children. But what she saw behind the kitchen door was completely sterile. She saw a lifeless room, where a few books in the wall shelves were ordered by size, a pair of green plants dutifully decorated the windows, and the sofa pillows had been plumped to perfection. That was the way they were, in the little world of Pammerow.

“The important thing is that you have sugar, or else I’ll be up a creek tomorrow.” Maria did. “I’ll get it back to you day after tomorrow at the latest, when the birthday party is over and the co-op is back in stock. Bye!”

Katharina hurried back. Inadvertently she cast a critical eye around her house. She knew that she, too, would have excused the mess to an unexpected visitor. That was something she’d picked up. Her mother always told her, “Your living room should look like anyone could drop in at any time. Otherwise people might talk about you. And your underwear should be clean in case you have an accident and they have to undress you at the hospital.” Potemkin villages were very important in this country. First priority was what you put up for others to see, then your own well-being came second. Katharina knew that. Worthless aluminum money wasn’t part of it. Of cars as status symbols or the destructive influence of fashion on the mental health of children in school, Katharina knew absolutely nothing, completely unaware in her small little world.

But on the other end of Grandma Hanschke’s garden was a gate out of this little world. Lead by her hand, little Olaf stood marveling by the wire grating, behind which clucking chickens laid their eggs, and by the hand-built rabbit hutch, where at Easter in the spring time the little Easter bunnies hopped around. The most interesting thing seemed to be the secrets beyond the gate, where another world rushed by. He marveled open-mouthed at the racketing monstrosity of a steam engine train that was practically thundering through the garden. Grandma Hanschke’s house stood directly in front of the high railroad embankment, where the trains roared past on their way back to Leipzig, and the heavy freight trains made the tracks clatter. But some trains also bore metal signs, that were hard to read fast enough from the garden, and rattled past to the unfamiliar destination of Hamburg. Day after day. But it was still met with astonishment in the tiny world of Grandma Hanschke’s narrow horizon.

In Katharina, however, it awoke a vague feeling of wanderlust. Hamburg, in another part of Germany, felt just as far away as the London from her English class she’d dreamed of, as though a closed door stood between her and where she longed to go. In both cases, it was a famous city and the capital of a country whose language, features, and traditions she had only studied for four years, without ever being able to go there, much less make contact with the inhabitants.

So Grandma Hanschke’s garden also held a certain fascination for Katharina, with its gate to forbidden dreams. The glorious London in her imagination came solely from the pages and pictures of an English lesson book. She was missing the real connection to the people living there, and it brought her crashing back down to reality. She pictured in her mind’s eye her idealized version of London, a bastion of magnificence. Aware that she would never be able to travel there, Katharina’s longing developed into an obsession, and her unrealistic, dreamy imaginings twisted her perception – it was magical there, like heaven – with free, happy people, fine culture, always green grass, curiosities older than the dirt itself, proof of its noble history, and a contented royal palace, whose merry children wanted for nothing. This heavenly delusion culminated in imagining a rich city without borders, where many different races of people lived together in peace and harmony. She spun fantasies, dreaming of this other world, of heaven on earth.

Wednesday, September 4th, 1996

Felix has his operation today. The operation will take almost four hours. I’m leaving Rostock after the first hour of class, so I’ll arrive at about 11. Grandpa will be coming with me again. I don’t know who worries more, my father about me, or me about my father. His strong meds have curbed his depression for twenty years now. We’re waiting on the first results from Professor Nahm.

This conversation opens up the blackest day in my life: malignant cancerous tissue in Felix’s head, right on the hypophysis, the central gland of the whole human system. Total cessation of hormone production, loss of sight, and failure to regulate water balance. Impossible to treat without incurring severe damage, if at all.

What happened to me afterwards, I don’t remember right now. Suddenly Karl and Grandma were standing there. They appeared to be beyond the point of anxiety. I also don’t remember how I got back. Blackout.

Everything I’ve ever done in my life suddenly seems to be dissolving into meaninglessness. What really is the meaning in life?

One of the many short stories about meaning in life in the seventh grade lesson book was called “Der Fahrplanschuster,” by Günter and Johanna Braun. For the second time Katharina found herself teaching the dubiously optimistic story of the Train Schedule Shoemaker, about a shoemaker who used to (i.e., before World War II) indulge in a curious hobby. The first time, it had been for a unit test on German in a seventh grade classroom, for her teaching degree at Humboldt University Berlin. It had been a success. So she never doubted being able to translate it perfectly into a classroom context, using her prepared questions and answers again word for word.

In the 1930’s, the shoemaker fellow’s favorite book was the train schedule for the German State Railroad. There, he found fine-sounding names of great cities of the world, like Amsterdam, Stockholm, New York, or Corpus Christi, Texas, but also tiny villages in Württemberg or Oderbayern. He could only dream of fulfilling his longing to travel, though, because the poor shoemaker didn’t have the means. But he dwelled on his fantasy escapades all the more, traveling in his mind beyond the borders that in reality fenced him in. In this way he experienced the wide world, a passionate expert on worldly train connections from his timetable, his unsophisticated substitute for real travel.

The incredible art of reading a train schedule and piecing together the most ingenious travel itinerary in the world was equally as difficult as learning a foreign language that you needed in order to travel. And Heimerich the shoemaker perfected the dream of traveling in his fantasy world to the minutest detail, knowing there was no possibility of being able to apply it to the real world.

When the narrator happened to meet the old man again after the war, he told Heimerich that they were now a cooperative society, and when he asked him about train connections, just as he had before, the shoemaker said in surprise, “No idea.” But he would have always known the schedule before, the narrator observed. “Yes, befo-ore,” he said, dragging the word out. “Now I travel myself.”

The eyes of the children in her seventh grade class were glued to her lips and there was absolute silence as she read them the story of Fahrplanschuster. Thirty-six pairs of eyes followed the narration attentively. Katharina encouraged the candor and gentleness of these children, who sat surprisingly politely at their tables, hands resting on the bench, materials stacked in a pile on the upper right corner of the tabletop. The experience with city children during her teacher training in Berlin had been completely different. In contrast to the insolent, feisty, disruptive, jumpy and unfocused students there, she felt like here, in the seventh decade of the twentieth century, she had gone back to paradise.

Katharina asked the questions from the reading book on page 94. Even though the questions sounded dry, the children responded eagerly. They raised their hands and waved them excitedly in the air, because they couldn’t all talk at once. They seemed so bright!

“What do we learn about the Fahrplanschuster from the description of his appearance in the first part of the narrative?”

“He has had to work hard.”

“Think about the way things were before – and the working conditions for the shoemaker and explain the reasons behind his hobby?”

“He was just the assistant in bleak old Winsleben, didn’t own anything, and didn’t have much money. He couldn’t travel. He could imagine traveling really easy, just like you can imagine heaven even though no one’s there.”

“Why did the shoemaker give up his old hobby?”

“Because now he lived in a country where things were better for the working people and now he was free to travel to all the places that before he could only dream about.”

It was that simple. Katharina worked through the questions and was pleased by her class’s lively cooperation.

Without thinking about the enormity of the statement, she had lead the children to the incredible understanding that the freedom of unlimited travel was a symbol for happiness, and that the defining trait of socialism was traveling by oneself.

And thus she did the same over and over in her career as a German teacher. Every time, in the same way and fashion, according to plan from the centrally provided teaching aid in the reading book. Always the same pattern. The knowledge of the Train Schedule Shoemaker Heimerich was kept in one of the various drawers of her brain, which she pulled out when planning lessons. Her own inability to travel by herself to England stayed in a different drawer. Her subconscious didn’t protest and she never discovered that there was a painful, unrecognized connection there.

Thursday, September 5th, 1996

I’m driving with Karl to Greifswald to the university clinic. He wants to see for himself how his son is doing.

Felix greets us cheerfully in the intensive care unit with tubes ripped out. He had answered the unit door when we rang, the nurse responsible being occupied elsewhere.

His memory is completely impaired; he talks only nonsense, but keeps up a lively stream of conversation. “Go into the living room, I’ll be right there.”

“Our black cat from Pammerow keeps coming in through the window, that’s why I sleep against the wall.”

“We got grass to eat today, because the lawnmower is here.”

“I was in heaven before, but there was no one there. So I came back.”

Mark Twain? Why in this moment does the memory of the story “The Mysterious Stranger” surface in me? – A person pleading to be made happy, the devil obliging by robbing him of his senses.

Karl says nothing, upset, and doesn’t speak a single word on the way back home either.

“You are out of your mind! We can’t just do something that’s not in the education laws.” Principal Hollenkamp tried to curb the enthusiasm of his young colleague. His easygoing nature sometimes left him floundering a bit, when it came to the balance between common sense and bureaucracy. It only became dangerous when it came down to his credibility regarding the politics of this state. In that area he would not deviate even the remotest degree from regulation, even if it was a matter of life and death.

She wanted to persuade Hollenkamp to let her seventh grade class take part in English classes for the first time in Pammerow.

“I know English classes are only optional, but that’s dependent on there being enough qualified English teachers for the whole country. But I’m right here now. And why should only a few students ever have the chance to learn a foreign language?”

“Alright. On a trial basis. But if anyone complains, we’re getting rid of it.”

“Yes, yes, I know. English can’t exactly be a compulsory class. No one needs it in the GDR,” she teased. “And as the language of the political enemy, it’s still just a barely tolerated step-child in comparison to Russian classes.”

“Stop it.” Hollenkamp fended her off angrily. “I will support your attempt. But with stuff like that you can very quickly get in a load of hot water.”

“What a bunch of baloney,” said Katharina, carelessly voicing her reaction out loud as always. She didn’t know any other way.

It was almost revolutionary when, in 1972, for the first time, the television was integrated into her seventh grade class. Once a week she launched the new unit with twenty minutes of “English For You” with Daphne Lösau. She must have been the only native English speaker in the GDR, who could or would want to be used for that. As a young student she married a German professor. Love can convince people to leave their own home countries. For the GDR. The reverse situation would have been called treason.

The children watched and paid careful attention. Television in class! What an unbelievable privilege!

“Can we watch TV again first hour on Tuesday?” asked little Thomas.

“Yes, of course, learning from real native English speakers is the best way!”

“This would never happen in Pammerow!” his bench neighbor Gitti exulted.

“Well, then it really is high time! We don’t want to let Mecklenburg sink a full hundred years behind the rest of the world.”

“But I don’t understand that,” said Thomas. Since Katharina knew that these words had something to do with a historically glossed over Bismarck, she let the ironic little observation fizzle out. “And you don’t need to,” she consoled the young ones.