Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

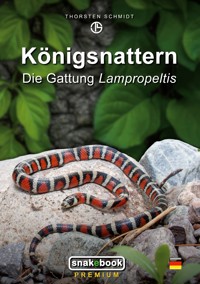

The kingsnakes and milksnakes of the Lampropeltis genus have been among the most popular snakes in terrariums for many years. Their manageable body size, bright colors and comparatively uncomplicated husbandry requirements make most species of non-venomous snakes suitable for beginners in the terrarium hobby. In the past decade, new studies have led to extensive changes in the taxonomic systematics of the king snakes. This book summarizes the currently valid taxonomy of the entire genus Lampropeltis for the first time and thus pursues the approach of promoting the hitherto reluctant acceptance of the use of the valid nomenclature. The author has kept various species of kingsnakes and milksnakes for around 30 years and provides an insight into his husbandry and breeding methods.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 389

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of contents

Preliminary notes

The snakebook project

Warning and exclusion of liability

Acknowledgments

I. General section

Classification system

Preliminary remark

Of kingsnakes, milksnakes and “chainsnakes“

The kingsnakes and milksnakes in the animal kingdom

Description

General physical characteristics

Scales, coloration and pattern

Teeth

Keeping

Legal requirements

The terrarium

Nutrition

Breeding

Sex determination

Hibernation

Mating

Egg laying

Incubation

Rearing

II. Species section

The

getula

complex

Lampropeltis californiae

Lampropeltis catalinensis

Lampropeltis floridana

Lampropeltis getula

Lampropeltis holbrooki

Lampropeltis meansi

Lampropeltis nigra

Lampropeltis nigrita

Lampropeltis splendida

The

triangulum

complex

Lampropeltis abnorma

Lampropeltis annulata

Lampropeltis elapsoides

Lampropeltis gentilis

Lampropeltis micropholis

Lampropeltis polyzona

Lampropeltis triangulum

The

mexicana

complex

Lampropeltis

alterna

Lampropeltis greeri

Lampropeltis

leonis

Lampropeltis mexicana

Lampropeltis ruthveni

Lampropeltis webbi

The Mountain Kingsnakes

Lampropeltis knoblochi

Lampropeltis multifasciata

Lampropeltis pyromelana

Lampropeltis zonata

The Prairie Kingsnakes and Mole Kingsnakes

Lampropeltis calligaster

Lampropeltis occipitolineata

Lampropeltis rhombomaculata

The Short-tailed Kingsnake

Lampropeltis extenuata

In my matter

Appendix

Tabular overview of the classification of earlier taxa

Table 1: Historical classification

Table 2: Current classification

Preliminary notes

The snakebook project

I have been writing specialist articles and books about keeping snakes since 1996. Of course, in the years since I have been involved in keeping these fascinating animals, I have acquired a lot of literature, including specialist journals, often just because of a single article about a particular snake species, of which around 80% of the content did not interest me at all. There are now quite a few monographic books on individual snakes, most of which are also very good works. However, these often come at a price due to the opulent layout with lots of glossy photos.

With the snakebook project, I am pursuing the approach of summarizing the practical experience I have gained over many years of keeping snakes in a compact form and making it available as an e-book at a very reasonable price. However, for those readers who still prefer to hold a printed book in their hands, I also make this form of publication available. By limiting the number of color images in standard quality, the costs can be kept low.

The small booklets in the snakebook Standard series are therefore not intended to compete with other, particularly better-equipped works, but rather as a cost-effective and species-specific supplement. In addition, more comprehensive works with extended features will occasionally be published, such as this book you are holding in your hand. The snakebook Premium series is intended for this purpose.

You, dear reader, are expressly invited to take part in the snakebook project and become a non-fiction author yourself! If you have successfully kept and bred one or other snake species, you are welcome to contact me so that we can publish a corresponding work together. Just write me a message to

and let me know which species you would like to contribute information on and publish a book with me. It is not necessary for you to be familiar with the current systematics, the climatic data in the distribution area, the bibliographies etc. for this. It is sufficient if you can provide information about your husbandry and breeding conditions and have some representative pictures of your animals. I will take care of the rest. You can find further information at

→ snakebook.jimdosite.com

Warning and exclusion of liability

In this book, I present procedures and conditions that have proved successful for me in keeping snakes in terrariums. However, all animals, including snakes, have individual requirements, so the information about a species is only ever generalized and must be adapted to the individual circumstances and needs of the individual animal. I hereby exclude any liability for damage to property and personal injury resulting from the imitation of the keeping conditions described here.

Acknowledgments

This book was an important concern for me, as the kingsnakes and milksnakes have been particularly close to my heart throughout my years of enthusiasm for snakes. Since the first books I read about these animals and during many years of personal experience in keeping and breeding, an incredible amount has happened in this genus. The fact is that this book could never have been written without the selfless support of terrarium enthusiasts, snake breeders, field herpetologists and nature/animal photographers. It is absolutely remarkable how willingly and kindly these people have helped me with information about the behavior of kingsnakes in the wild and photos. I would therefore like to thank the following people from the bottom of my heart:

Andrew Austin, Todd Battey, Devin Bergquist, Daniel Carhuff, Saunders Drukker, Kyle L. Elmore, Bob Ferguson, Raul Fernandez, Ryan Ferrell, Noah K. Fields, Matt Gruen, Nicholas Hess (nicholashessphotography.com), Michael Heyduk, Brian Hubbs, Jason Jones (herp.mx), Rye Jones, Mark Kenderdine, Chad M. Lane, Deborah & John Lassiter, Jim Markle, Peter Paplanus, Jay Paredes, Mike Pingleton, Jacobo Quero, Kory G. Roberts, Raul Solis-McGarity, Tim Warfel, John Worden, Jules Wyman and the FWC Fish & Wildlife Research Institute.

I would like to expressly thank Christian Riemann for the loan of signed and high-quality editions of specialist literature, which have served me well in compiling information.

Finally, I would like to thank the test readers Sigi Nägele and Jörg Kollenbroich as well as the expert on kingsnakes in German-speaking countries, Michael Heyduk, for critically reviewing the manuscript.

The English-language edition was linguistically and technically reviewed by Canaan Alexander, for whose work I would also like to take this opportunity to thank him.

I. General section

The kingsnakes and milksnakes of the genus Lampropeltis have everything that most snake keepers want from their animals. They have extremely attractive coloration and pattern, can be kept with manageable effort and usually reproduce willingly. At the same time, they are very persistent in the terrarium if kept well and the genus is so diverse and varied in size and appearance that there is something for virtually every taste. It is therefore no wonder that demand was significantly higher than supply in the mid to late 1990s and kingsnakes or milksnakes were sold for high prices. However, the fact that they are fairly easy to breed meant that over time some subspecies became quite common and the demand for these animals stagnated. Only rarely encountered subspecies were still on the wish lists of snake enthusiasts and so the supply of kingsnakes at reptile expos declined noticeably due to lower demand. In recent years, however, more people have become interested in these beautiful snakes again. Today, much more is known about their relationships as well as locale and patterned forms, so that there are interesting areas of specialization for serious breeders. In the meantime, stable breeding lines of species that were previously classified as "non-durable" have also been established, e.g. because the young of one species or another were very difficult to feed. However, since almost all kingsnakes and milksnakes in the United States and Europe come from captive-bred stock, such problems have become rare. As a result, many species and subspecies of the genus Lampropeltis are now available to interested terrarium keepers, and whereas in the past corn snakes or garter snakes were recommended to beginners in our hobby as so-called beginner snakes, nowadays well feeding kingsnakes and milksnakes from established breeding stock are also suitable for beginners in snake keeping.

Classification system

Preliminary remark

Long-time friends of kingsnakes will certainly be surprised and confused by the classification system used in this book. In fact, I feel the same way myself. The main reason for this is that a comprehensive revision of the genus Lampropeltis took place in 2014. This revision is based on the work of biologists Sara RUANE, Robert W. BRYSON, Jr., R. Alexander PYRON and Frank T. BURBRINK, who have established on the basis of extensive research, including molecular biological investigations, that the previously listed species and their subordinate subspecies cannot exist in this form. As a result, we now find that species and subspecies whose existence and key identification clues we have been accustomed to for many years have been deleted and combined into other species. However, there are also other more recent works that justify the current nomenclature. I will go into the details in the species section.

If you look through the relevant offers of captive-bred animals nowadays, you can see that the new nomenclature is hardly accepted, even though it is already several years old. In fact, however, the current nomenclature applies, which is why only the current state of research is taken into account in this work. However, for all descriptions in the species section, I will go into detail about which earlier subspecies, local and pattern variants are included and which synonyms were previously used for the respective animals. For a quick overview of the current classification, please refer to the tables in the appendix.

Overall, the diversity of species within the genus Lampropeltis has increased significantly as a result of the revision, while the number of recognized subspecies has been almost completely reduced. However, this has led to many animals that could previously be identified very precisely as subspecies on the basis of certain physical characteristics, in particular their pattern, are now being classified merely as local variants. The extent to which this will affect the future mixing of these characteristics in terrarium keeping and the breeding of these animals cannot be predicted at present. Personally, I am hopeful that the gradation from subspecies to local variants will not result in a mixture of traits, but rather that breeders will attach more importance to maintaining the purest possible lines of local variants and breed in a highly selective manner. The development in breeding of some boid snakes (Boa constrictor, Boa imperator) shows that this can work.

According to current opinion, the genus Lampropeltis comprises 30 species, of which only one species is still divided into subspecies (Lampropeltis pyromelana: 2 subspecies). At first glance, it would therefore appear that the elimination of the enormous number of subspecies has simplified the handling of systematics and the identification of specimens. After all, the species Lampropeltis triangulum alone used to comprise 26 subspecies. However, with the currently valid systematics it must be taken into account that animals with very different pattern have now also been grouped into monotypic species. For example, the former Sinaloa Milksnake (ex. Lampropeltis triangulum sinaloae) and the former Pueblan Milksnake (ex. Lampropeltis triangulum campbelli) are currently assigned equally to the monotypic species Lampropeltis polyzona, although their body structure differs slightly and their markings are quite different. Presumably it is precisely these circumstances that are responsible for the fact that even almost a decade after the fundamental systematic reorganization, the obsolete nomenclature persists so stubbornly in the linguistic usage of terrarium enthusiasts.

It should also be mentioned at this point that the current systematics are also controversial among experienced field herpetologists and scientists in the USA and Mexico. The work of CHAMBERS & HILLIS should be mentioned here in particular, who question the systematics on the primary basis of genetic studies and, for example, assign all Central and South American specimens of the triangulum complex to the species Lampropeltis polyzona (with corresponding subspecies) and also cite Lampropetlis triangulum and Lampropeltis elapsoides as further species for specimens in North America. However, ITIS and SSAR do not (yet) follow this view. It can therefore be assumed that the genus Lampropeltis will continue to be subject to revisions in the future, even though the current investigations, taking phylogenetic criteria into account, have very strong arguments and are therefore not currently debatable.

Of kingsnakes, milksnakes and “chainsnakes“

The genus Lampropeltis was first described in 1843 by the Austrian zoologist Leopold FITZINGER (1802-1884). Until then, snakes that are now assigned to this genus were assigned to the few genera in common use at the time, mainly the generic term Coluber.

The (generic) term kingsnake used in the German-speaking world includes all species of the genus Lampropeltis. The term kingsnake is most likely due to the fact that it has been observed that some of these animals eat other snakes, including venomous snakes, and thus elevate themselves above the other snakes. (At the same time, kingsnakes can also become prey for other animals; their main predators in the wild are birds of prey (Falconiformes), cats (Felidae), coyotes (Canis latrans) and raccoons (Procyon lotor). They are also occasionally eaten by other snakes (e.g. Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) and, of course, other kingsnakes).

Leopold Fitzinger (1802-1884)

For animals from the getula complex, for which there is no separate name in American usage and which are also called "kingsnake" there, the term "Kettennatter" (chainsnake) has become established in German usage.

The term "milksnake" is also used to describe most tricolored kingsnakes, which were previously mainly assigned to the species Lampropeltis triangulum. The name comes from the superstition that these snakes would suck milk from grazing cattle - which is of course complete nonsense. The name triangle snake of this (former) species based on the scientific species name (triangulum) is, as far as I know, only common in German-speaking countries and needs to be reconsidered, at least after the revision. For this reason, the term milksnake will be used for the "new" species also in the German issue of this book and in accordance with the American common names.

Ultimately, complexes have been formed with reference to the earlier species, i.e. groups under which several species and subspecies have been grouped together on the basis of phenotypic characteristics, preferred habitats or behavior. Regardless of the new systematics, these complexes still help us today to identify similarities to individual species, which is why I want to follow the classification into these complexes in this book.

The complexes and groups can be summarized as follows:

The getula complex

Some kingsnakes belong to the getula complex, even if the designation chain snake is not always reflected in their German common names. There are nine species in this complex:

Lampropeltis californiae

Lampropeltis catalinensis

Lampropeltis floridana

Lampropeltis getula

Lampropeltis holbrooki

Lampropeltis meansi

Lampropeltis nigra

Lampropeltis nigrita

Lampropeltis splendida

The triangulum complex

The triangulum complex includes all tricolored milksnakes, which were previously classified as subspecies of Lampropeltis triangulum. According to the revision, seven species are included:

Lampropeltis abnorma

Lampropeltis annulata

Lampropeltis elapsoides

Lampropeltis gentilis

Lampropeltis micropholis

Lampropeltis polyzona

Lampropeltis triangulum

The mexicana complex

In addition to the three former subspecies of Lampropeltis mexicana, the mexicana complex also includes three other species from Mexico, so that a total of six species are assigned to this group:

Lampropeltis alterna

Lampropeltis greeri

Lampropeltis leonis

Lampropeltis mexicana

Lampropeltis ruthveni

Lampropeltis webbi

The Mountain Kingsnakes

The species Lampropeltis pyromelana and Lampropeltis zonata, each comprising several subspecies, were previously counted among the mountain kingsnakes. After the revision, these are now understood to be four independent species:

Lampropeltis knoblochi

Lampropeltis multifasciata

Lampropeltis pyromelana

Lampropeltis zonata

The Prairie Kingsnakes and Mole Kingsnakes

The three subspecies of the former species Lampropeltis calligaster have now each attained species status:

Lampropeltis calligaster

Lampropeltis occipitolineata

Lampropeltis rhombomaculata

The Short-tailed Kingsnake

Without assignment to a complex, the Short-tailed Kingsnake has recently been assigned to the genus Lampropeltis, which was previously assigned to the genus Stilosoma:

Lampropeltis extenuata

The kingsnakes and milksnakes in the animal kingdom

As a new-world snake genus, kingsnakes belong to the true colubrids (Colubrinae) and are classified as follows in the natural history systematics of the animal kingdom (Animalia):

Class

Reptilia

Reptiles

Superorder

Lepidosauria

Scaly lizards

Order

Squamata

Having scales

suborder

Serpentes

Snakes

Superfamily

Colubroidea

colubroid

family

Colubridae

colubrids

Subfamily

Colubrinae

True colubrids

genus

Lampropeltis

Kingsnakes

Description

Kingsnakes and milksnakes have been among the most popular snakes in terrariums for decades. They owe this to their moderate body size, which allows them to be kept in small to medium-sized tanks, as well as to their relatively easy keeping conditions, but especially to their shiny scales, which make many species of the genus extremely beautiful animals and absolute eye-catchers in the terrarium thanks to their bright colors and high-contrast markings. In this respect, the scientific name of the genus is definitely appropriate here, as Lampropeltis means "shining shield".

General physical characteristics

With body lengths between 35 cm (14 inches) and over 200 cm (79 inches), kingsnakes are small to medium-sized snakes. The wide range of body sizes already shows the great variability of the genus, which comprises many different species. In relation to their body length, most kingsnakes generally have a fairly slender build. However, one should not be deceived by this, as these are extremely muscular and strong animals. Depending on the species, the head is only slightly or barely noticeably separated from the body. The eyes are medium-sized with round pupils.

Scales, coloration and pattern

The most striking feature of the genus Lampropeltis is the splendidly colored scales of most species. As the scales of the dorsal rows of kingsnakes are not keeled and are usually quite large and rhombus-shaped, these snakes have a strikingly smooth and shiny appearance. In addition, there are the high-contrast patterns of markings, which essentially consist of the colors black, white and red, depending on the species in varying proportions or with different gradations, in which the light elements can also be gray or yellow instead of white. Many kingsnakes and especially the milksnakes show a pattern of bands of alternating colors. This striking coloration has not developed to give us humans pleasure in looking at the animals, but is an evolutionary development for the survival of the species. Now you might ask yourself how a snake with such striking colors and patterns should be camouflaged in nature and whether brown animals without patterns are not better equipped for the daily struggle for existence. In fact, however, the coloration and patterning of kingsnakes and milksnakes serve an essential purpose on several levels, which serves to protect the animals: On the one hand, we humans tend to look at the bright colors of the animals in isolation. In fact, it is difficult for a tricolored kingsnake to hide in a clearly arranged terrarium. From my own experience, however, I can say that these snakes are also difficult to spot on the ground in their natural habitat, especially if it is a forest floor with different colored leaves and interrupted light.

Some specimens of the Gray-banded Kingsnake Lampropeltis alterna look very similar to the Rock Rattlesnake Crotalus lepidus klauberi pictured here, which was found in Cochise County, Arizona. / Photo: Chad M. Lane

In the coral snakes shown here, you can see that the light-colored markings are adjacent to the red body rings. While the red elements of kingsnakes are always separated from the light-colored rings by black elements, this is not a reliable distinguishing criterion in the venomous species. left: Micruroides euryxanthus / Photo: Chad M. Lane

right: Micrurus fulvius / Photo: Deborah & John Lassiter

The aspect of a banded pattern also comes into play when the snake moves quickly. The alternating pattern makes it difficult for an observer (or predator) to determine and predict the direction of movement. We are also familiar with this effect from films, when the wheels of vehicles appear to turn in the opposite direction to the direction of movement. The effect is known as a stroboscopic illusion. This occurs when the inertia of the eye can no longer correctly distinguish between alternating patterns such as the spokes of a wheel or the colored bands of a snake due to the speed of movement.

Finally, the markings of kingsnakes can also lead to confusion with other snakes that occur in the same distribution area but can be very dangerous for predators or other troublemakers. These are, for example, coral snakes (genera Micrurus, Micruroides), which belong to the venomous snakes, but also some rattlesnakes; for example, the gray-black variant of Lampropeltis alterna looks very similar to the rock rattlesnake Crotalus lepidus klauberi. The development of such characteristics, which can lead to the deterrence of predators of supposedly dangerous animals, is known as mimicry. In the case of the tricolored kingsnakes and milksnakes, red, black and white or light yellow bands alternate, as is also the case with coral snakes.

However, in most coral snakes the light-colored markings are adjacent to the red ones, while in the kingsnakes the red markings are framed by black ones. In the USA, children are taught a rhyme to distinguish venomous from non-venomous species:

„Red on yellow kill a fellow,

red on black, a friend of Jack.“

But be careful: this general statement only applies to snakes in North America. In some venomous species in South America, black markings also border on red.

Drawing:

The details of a snake's head scales are essential features for identification down to species and subspecies level. For example, the number of upper and lower lip scales (supra- and sublabialia), the loreale or the anterior and posterior eye scales (pre- and postocularia) often vary.

The arrangement of the head scales of kingsnakes corresponds to the general scaling system of true snakes (Colubridae), albeit with slight numerical deviations at species and subspecies level. The details are discussed in detail in the species section. However, there are some characteristics that apply to the entire genus Lampropeltis:

Scales

Number

Features

Rostrale (a)

1

normal, clear demarcation

Internasalia (b)

2

normal

Parietalia (c)

2

normal

Präfrontalia (d)

2

normal

Supralabialia (e)

6-8

normal

Sublabialia (f)

7-12

normal

Präoculare (g)

1

normal

Postocularia (h)

2

normal

Temporalia (i)

3-5

arranged in two rows

Loreale (j)

1

normal

Dorsalia

17-27

normal

Ventralia

254-263

normal

Anale

1

undivided

Subcaudalia

59-73

arranged in pairs

The ventral scales (ventralia) appear as even rails, the anal shield can be divided or undivided depending on the species. The scales under the tail (subcaudalia) run in two rows.

Overall, the scales reveal the functional connection to the habitat of predominantly terrestrial and subterrestrial snakes. Although some kingsnakes also like to climb and welcome appropriate opportunities in the terrarium, the body structure and smooth scales do not indicate any specialization in the habitat of shrubs and trees.

Teeth

Kingsnakes and milksnakes belong to the same-toothed snakes, so their teeth are aquiline and consist of massive, more or less equally sized and evenly shaped, unfurrowed teeth. Unlike mammals, the teeth of snakes are not arranged in a row in the upper and lower jaw. Instead, the upper jaw consists of several areas, each of which is occupied by groups of teeth. Kingsnakes have 12-20 maxillary teeth in the upper jaw bone. In addition, there are 8-14 palatine teeth on the roof of the mouth and 12-23 pterygoid teeth on the wing bone. Together with the 12-18 dentary teeth in the divided lower jaw, the snakes have a total of 44-75 teeth. In the tricolored kingsnakes, i.e. the animals from the triangulum complex and the mountain kingsnakes, the posterior maxillary teeth are longer than the anterior ones.

The lower jaw consists of two independent jaw braces, on each of which a row of teeth is arranged. The lower jaw is therefore not fused together at the front. This gives the snake the advantage of being able to open its mouth sideways to swallow relatively large prey. In addition, it can alternately move the left and right lower jaw braces back and forth when swallowing, so that food animals can be gradually pulled into the gullet while still being held.

Drawing:

The skull of an even-toothed snake has massive, backward-facing retaining teeth in the upper and lower jaw. The lower jaws are not fused together but are independent of each other. This allows the snake to stretch its mouth very wide in order to swallow larger prey.

The tooth shape of agylph (lacking grooves) snakes is not suitable for transporting concentrated saliva into the tissue or bloodstream of prey or attackers, as is the case with snakes with furrowed (proteroglyphic) or hollow (solenoglyphic) teeth. The teeth are also not associated with venom glands. Although studies have shown that snakes with aglyphic teeth also have so-called Duvernoy's glands, in which a salivary secretion with toxic components is formed, there is no evidence that bites from kingsnakes or milksnakes can cause any systemic effects in humans.

Keeping

Kingsnakes and milksnakes are among the most popular snakes to keep in terrariums. In addition to their attractive appearance, this is also due to the fact that these animals are comparatively easy to keep. Due to their moderate size, they do not place unrealistic demands on their artificial habitat in terms of space requirements, and the preferred climatic conditions can also be reproduced for the keeper with fairly simple means. In this respect, kingsnakes in human care are relatively undemanding and persistent pets that can live to a very old age if kept well. For example, the age of a California Kingsnake (Lampropeltis californiae) kept in captivity has been documented as more than 33 years.

Legal requirements

Keeping species of the genus Lampropeltis in the USA is generally legal, but specific regulations may vary by state. It is crucial to research and adhere to local laws regarding reptile ownership. Some states may require permits or have restrictions on certain species to prevent the introduction of non-native species. Additionally the Lacey Act prohibits the interstate transportation of wildlife taken in violation of state regulations. Always consult with local authorities or reptile organizations to ensure compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Most species of the genus Lampropeltis are not endangered. There are therefore no species protection regulations in Germany or Europe that would regulate the acquisition, keeping or breeding of these animals. However, on August 2, 2022, Regulation (EU) No. 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of October 22, 2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species was amended by Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/1203 of July 12, 2022 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 in order to update the list of invasive alien species of Union concern, in which Lampropeltis getula is listed as an invasive species. I will discuss the effects of the still very current legal situation individually in the species chapters of the getula complex.

For individual species whose natural populations are declining or which may already be extinct or of which only a few specimens have been found, national protection regulations may also apply, although these only relate to the removal of wild animals. As a result, we have no regulations that would justify an obligation to provide evidence or similar.

In addition to species protection, animal welfare regulations must of course also be taken into account. This means that every pet owner should inform themselves thoroughly about the needs of the species to be kept in order to be on the safe side, not only morally but also legally. As we will regularly strive to keep our animals alive and healthy for as long as possible and ideally also to reproduce them, species-appropriate husbandry should be a matter of course for us anyway. In addition to a suitable terrarium with the right climatic conditions, this also includes an appropriate diet and constant access to drinking water.

The terrarium

In Germany, there is an expert opinion on the minimum requirements for keeping reptiles and amphibians, issued by the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture. For the genus Lampropeltis, the report stipulates a container size of 1.0 x 0.5 x 0.5 (LWH (length x width x height)). These values are factors to be multiplied by the total length of the snake to be kept and are to be understood as a guide value for keeping in pairs. For group keeping, 20% should be added to the calculated values for each additional animal. So if we want to keep a pair of kingsnakes or milksnakes with a total length of 70 cm (28 inches) each, the dimensions of the terrarium should be at least 70 x 35 x 35 cm (28 x 14 x 14 inches) (LWH), for a group of three animals of the same size we would have 84 x 42 x 42 cm (33 x 17 x 17 inches) (LWH). For larger animals, such as a group of three Lampropeltis abnorma from Honduras with a total length of 140 cm (55 inches), the minimum size is 168 x 84 x 84 cm (66 x 33 x 33 inches) (LWH). When planning a terrarium enclosure, you should therefore consider not only the expected total size of the animals but also the composition of pairs or groups. As kingsnakes and milksnakes are quite active snakes, I prefer slightly larger containers and have had good experiences with them. You can plan additional resting areas in terrariums at half height, so that the animals actually have more floor space available. Nevertheless, in my opinion, the above-mentioned multiplication factors should not be significantly undercut.

Substrate

As an artificial habitat for our animals, the terrarium must fulfill other conditions in addition to size so that the snakes feel comfortable here and can lead a healthy, long life. The first question that arises here is the right substrate. Finding an answer to this question is not necessarily easy for beginners in snake keeping, because if you ask five different terrarium keepers, you may well get five different answers. This does not mean that one answer is wrong. Ultimately, the right answer is the one that works and doesn't cause any problems for our animals. Problems could arise, for example, if the substrate is highly absorbent (cat litter, clay, etc.). If a snake were to get one or more pieces of such substrate in its mouth while digging or eating, the highly absorbent effect could ensure that all the saliva is absorbed and the snake cannot free itself from the piece. Swallowing such pieces of substrate can cause considerable damage to health (intestinal obstruction etc.). Very fine sand, on the other hand, could get under the scales and cause inflammation. It would go too far to discuss the pros and cons of all conceivable substrate types here. I have tried various substrates over many years with various species of kingsnakes, all of which have ultimately worked for the snakes. These included bedding types such as softwood shavings, hemp bedding or linseed straw as well as peat-sand mixtures, expanded clay granules, beech wood shavings, gravel, coconut fiber, bark mulch and a few others. The only advantages or disadvantages were in terms of appearance and cleaning. Small rodent litter (Care-Fresh, etc.) is very inexpensive, excrement is well bound and can be detected quickly. However, the material creates a lot of dust when it is completely replaced and naturally does not look particularly good. Other materials do not create dust, but are heavy, not absorbent or relatively expensive. The snakes, on the other hand, seemed largely indifferent to the differences in the substrate. I have therefore started to use a mixture in my terrariums for kingsnakes and milksnakes that on the one hand meets my requirements for an attractive appearance and low-dust processing, is not too expensive and at the same time offers the animals a behaviorally appropriate, burrowable substrate. After several years of experimenting, I finally used a mixture of pine bark with a grain size of 4-8 mm, a mineral void filler and some play sand from the DIY store. However, I am currently converting all my Lampropeltis terrariums to biological self-cleaning, so that the substrate consists of a mixture of top soil, pine bark and dolomite lime, mixed with white rotten wood and covered with a top layer of leaves, moss and pieces of bark. This substrate is kept slightly moist at all times so that isopods can live in it, feeding on the excrement of my snakes and converting organic material into mineral salts. This type of substrate looks very natural and decorative, creates a positive terrarium climate and significantly reduces cleaning intervals. The environmental factors required for keeping isopods in parallel are a science in themselves, which is why we will not go into them in detail here. If you are interested, you can find lots of useful information on the internet. In my Lampropeltis tanks I use the isopod species Porcellio laevis in the orange and "Panda" varieties, with which I have had good experiences.

By using a soil mixture with a top layer of deciduous forest leaves, you can achieve a natural-looking substrate, as seen here in a terrarium for Lampropeltis polyzona (local variant Sinaloa). If the substrate is always kept slightly moist, the habitat is suitable for isopods, which feed on the snakes' excretions and thus act as soil police. / Photos: Thorsten Schmidt

Lighting

The primary function of the lighting in the snake terrarium is, of course, to simulate a day-night rhythm for the animals. By adjusting the duration of lighting, we can also simulate seasonal changes if this is indicated by the geographical distribution of individual species. What is neglected by many keepers, however, is the correlation between light and the biochemical processes for synthesizing important vitamins in snakes. Numerous studies have shown that vitamin D3, which regulates the calcium level in the blood and is an important component for bone development, is produced in the body itself when the skin is exposed to UV-B radiation. This is non-visible light in the wavelength range between 280 and 315 nm. The visible range of the light spectrum is between 400 and 800 nm. Conventional lamps, for example fluorescent tubes, LED or halogen spotlights in the color warm white move in this visible light spectrum, with a focus in the range between 550 and 700 nm.

The scale shows the light spectrum. Most people can perceive wavelengths between approximately 400 nm and 780 nm with their eyes. The range below this wavelength is called ultraviolet (UV), the range above the visible range is called infrared (IR). Natural sunlight emits the full electromagnetic spectrum, although the proportion of radiation varies throughout the day. For example, the larger proportion at midday is usually between 420 and 580 nm, so that the blue component of the light predominates at this time. At sunset, the radiation range between 600 and 750 nm predominates, so that a higher red component is perceived at this time. Both fluorescent energy-saving lamps and standard LED spotlights emit light with narrowly defined components in the wavelength range between 550 and 650 nm. With halogen spotlights, the spectrum increases continuously from 350 to well over 750 nm, whereby the UV radiation is very low but the IR radiation is very high. This is also the reason for the high radiant heat emitted by halogen lamps. Even with an LED lamp of the "Daylight" type, there is an overhang in the range between 450 and 550 nm, which reflects the optical perception of daylight at midday, but even these lamps hardly offer any measurable UV components.

This means that this type of lighting cannot contribute to the build of the important vitamin D3. This is problematic, because while other vitamins and trace elements are absorbed by snakes in sufficient quantities through food, this is only possible for vitamin D3 through supplementation. This in turn entails the risk of overdosing, which can lead to organ dysfunction (e.g. kidneys). It therefore makes more sense to enable the animals to synthesize vitamin D3 naturally in the body by providing suitable lighting. This can be achieved by using light sources with a daylight spectrum or full spectrum, which also emit a certain amount of UV-B radiation. However, modern light sources (LEDs) with full spectrum are quite expensive, so the option of simply planning one more spotlight that only illuminates the tank with UV light on an hourly basis is a practicable solution.

A view into one of my terrariums for Lampropeltis polyzona (local variant Sinaloa). Various spotlights are mounted on the ceiling in a triangular arrangement: an LED UV spotlight at the back left and a standard LED lamp (warm white) at the back right. A halogen spotlight, which is controlled by a thermostat, is fitted in the middle at the front. The heated air rising centrally at the front can escape through the central ventilation grille in the rear wall, creating an air flow and automatically creating cooler temperature areas in the rear side areas.

The picture shows a section of my terrarium system at dusk or dawn, when the tanks are illuminated exclusively by the UV lamps. The spotlights are switched so that they shine for 45 minutes each in the morning and evening and supplement the standard spotlight for 60 minutes at midday. / Photos: Thorsten Schmidt

Temperature

Depending on the origin of the kingsnakes and milksnakes, the additional heating of an insulated terrarium in a living room may not be necessary, especially as several species are found in temperate latitudes, where the temperatures throughout the year are very similar to the conditions in our regions. Due to the large differences within the huge distribution area of the genus Lampropeltis, in which these animals have conquered a wide variety of habitats, I recommend taking a very close look at the species to be kept in terms of its natural distribution. For example, montane species from Mexico have different requirements to animals from the lowlands of Florida and animals from temperate latitudes in the north of the USA should be kept differently to tropical species from the Costa Rican rainforest. I have included climate diagrams of the typical distribution area for each species in the species section to give an indication of the correct temperature ranges.

There are several options for heating the terrarium. There are various devices for heating our tanks that are equally suitable, e.g. heating mats that can be laid under the substrate, heating stones or so-called heat panels that are attached under the ceiling. Which option you choose is ultimately a matter of taste and also depends on how well our terrarium is insulated. For example, pure glass tanks have good thermal conductivity, which means that the inside temperature is very strongly influenced by the outside temperature. Enclosures made of wood or plastic (XPS, PVC, etc.) panels, on the other hand, have very efficient thermal insulation, meaning that the energy required to ensure higher internal temperatures is much lower. Personally, I have decided to heat my cages (XPS or wood construction) using radiant heat from thermostat-controlled halogen spotlights. I see the advantages of this in the fact that an additional light source is available and the heat does not come from below but from above, as is the case in nature. I do not place the heat lamps in the middle of the tank, but at the edge, so that there is a temperature gradient over the depth, which allows the animals to choose between cooler and warmer areas.

Ventilation

Another controversial topic among terrarium keepers is the correct ventilation of a terrarium. Ventilation areas that are too small can lead to a stuffy climate, waterlogging and mold infestation, especially in forest or rainforest terrariums with correspondingly high humidity. Ventilation areas that are too large, on the other hand, can lead to draughts and make it difficult or even impossible to achieve the desired humidity. The correct positioning of ventilation areas, on the other hand, in conjunction with temperature zones in the tank, can help to transport and circulate fresh air. I have had good experiences with placing ventilation areas opposite the sliding windows, i.e. at the top of the rear wall of the terrarium. The size ratio of the ventilation areas depends on the volume of the terrarium. For terrariums that are not permanently humid, I consider a ventilation area of around 20% of the volume of the terrarium to be sufficient. Example: A terrarium measuring 100 x 50 x 50 cm has a volume of 250 liters. 20% of this would be 50 cm in square, so a ventilation area of 10 x 5 cm would be sufficient in my opinion. The installation opposite the front windows ensures that air movement takes place and fresh air is constantly supplied. The fact that it is mounted close to the ceiling means that rising warm air is dissipated by convection and fresh air is drawn in through the gap in the sliding windows. I am aware that many keepers consider it necessary to install more or larger vents, but I have had good experiences with the described construction method over the past 30 years of keeping terrarium animals, keeping many animals for years and successfully breeding them. In this respect, this form of keeping cannot be completely wrong.

Nutrition

Nutrition is of particular importance for kingsnakes and milksnakes. Not only because adequate nutrition is, of course, a decisive criterion for the health, development and lifespan of our animals; after all, this applies to all animals that are kept in human care. However, when keeping kingsnakes and milksnakes, it is important to bear in mind that the diet of some species also includes other snakes. This food preference is known as ophiophagy. There are even snakes that feed almost exclusively on other snakes. One example of this is the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) from Asia. Most kingsnakes and milksnakes, on the other hand, are food opportunists that generally accept a wide range of prey, but some species also feed on other snakes. Species of the kingsnakes (getula complex), but also some milksnakes (e.g. Lampropeltis micropholis (ex. triangulum gaigeae)) have been shown to regularly prey on and eat other snakes in the wild, including rattlesnakes.

This aspect is very important for keeping snakes in terrariums, as we have to assess whether or not it is possible to keep certain species in pairs or groups. I myself have observed that many species could be kept in pairs or small groups for years without any problems and without any failures. There is obviously no fundamental ophiophagous tendency in these species.

Various kingsnakes feed ophiophagously in the wild, i.e. they eat other snakes. Thanks to their enormous muscular strength, they can also capture and kill snakes that are the same size or even larger than themselves. Here you can see a Californian Kingsnake (Lampropeltis californiae) that was successful in the hunt / Photos: Nicholas Hess

A Speckled Kingsnake (Lampropeltis holbrooki) has captured another snake and is eating it head first / Photo: Kory G. Roberts

Other snakes are also part of the food spectrum for kingsnakes outside the getula complex. Here, a Black Milksnake (Lampropeltis micropholis) kills a cribo (Drymarchon melanurus), interestingly a species that also feeds on other snakes. / Photo: Raul Fernandez

The vast majority of kingsnakes in captivity accept mice as their sole food. This young Gray-banded Kingsnake (Lampropeltis alterna) has no problem swallowing a mouse the size of a hopper, even though the size of the food animal is larger than the snake's head. The movable clasps of the lower jaw and the enormous elasticity of the esophagus enable the animals to swallow even relatively large prey. It has proven to be a good idea to choose the size of the prey so that the circumference corresponds to that of the snake at the thickest part of its body / Photos: Thorsten Schmidt

Some kingsnakes also like to eat day-old chicks, such as this adult male of the California Kingsnake (Lampropeltis californiae, high-white variant). Due to their low fat content, however, chicks are not suitable as complete food for females intended for breeding. / Photo: Thorsten Schmidt

Other species, on the other hand, are known not to stop at conspecifics when they are hungry. Particularly in animals from the getula complex, many keepers have already experienced cases where a snake has eaten its partner. In addition to the possibly extinct Lampropeltis catalinensis, this complex includes the present-day species

Lampropeltis californiae

Lampropeltis floridana

Lampropeltis getula

Lampropeltis holbrooki

Lampropeltis meansi

Lampropeltis nigra

Lampropeltis nigrita

Lampropeltis splendida

I will deal with corresponding tendencies separately in the species section.

Overall, the diet of most kingsnakes and milksnakes does not pose any problems for the keeper. In fact, acclimatized offspring of many species generally accept reliably thawed frozen food of a suitable size. My animals all eat colored mice, African Soft-furred mice, small rats and day-old chicks without any problems. I make the feeding intervals dependent on the age of the animals. Young animals up to the age of one year are offered food about every 5-7 days. Up to the age of 2 years, I feed them about every 7-10 days and adult animals get food about every 14 days. However, there are also aspects that indicate shorter intervals. For example, if a female refuses to eat during the last few weeks of pregnancy and has lost weight after laying her eggs, more frequent feeding is of course advisable so that the animal can put on weight again.

The size of the food animals should always correspond to the size of the snake. Especially beginners in snake keeping often underestimate the ability of their fosterlings to devour prey. I have had good experiences with this when I have selected food animals whose diameter corresponds approximately to the thickest part of the snake's body.

Breeding

Most snake keepers have the intention of reproducing the animals they keep. On the one hand, regular offspring are an indication that the husbandry conditions for the animals are sufficiently good that their instincts allow them to reproduce. In addition, terrarium keepers ensure in this way that the demand for captive-bred animals can be met, thus reducing or even completely avoiding the need to take animals from the wild. Ultimately, most breeders will sell the young animals to interested hobbyists and thus be able to cover some of the costs of keeping snakes.

Sex determination

For reproduction, it is of course essential to have animals of both sexes of a species. While the sex of some snakes can be determined solely on the basis of very striking morphological differences (such as the threefold tail length of male Hognose snakes (Heterodon nasicus)), the sex of kingsnakes is not quite so easy to diagnose. Although males of the genus Lampropeltis also have longer tails with a broader base, the differences are often so small that these physical characteristics do not allow a reliable determination.