Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

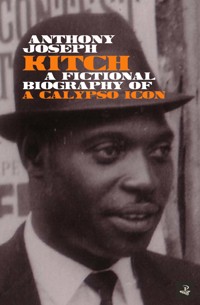

The poet and musician Anthony Joseph met and spoke to Lord Kitchener just once, in 1984, when he found the calypso icon standing alone for a moment in the heat of Port of Spain's Queen's Park Savannah, one Carnival Monday afternoon. It was a pivotal meeting in which the great calypsonian, outlined his musical vision, an event which forms a moving epilogue to Kitch, Joseph's unique biography of the Grandmaster. Lord Kitchener (1922 - 2000) was one of the most iconic and prolific calypso artists of the 20th century. He was one of calypso's most loved exponents, an always elegantly dressed troubadour with old time male charisma and the ability to tap into the musical and cultural consciousness of the Caribbean experience. Born into colonial Trinidad in 1922, he emerged in the 1950s, at the forefront of multicultural Britain, acting as an intermediary between the growing Caribbean community, the islands they had left behind, and the often hostile conditions of life in post War Britain. In the process Kitch, as he was affectionally called, single handedly popularised the calypso in Britain. Kitch represents the first biographical study of Aldwyn Roberts, according to calypso lore, christened Lord Kitchener, because of his stature and enthusiasm for the art form. Utilising an innovative, polyvocal style which combines life-writing with poetic prose, the narrative alternates between first person anecdotes by Kitchener's fellow calypsonians, musicians, lovers and rivals, and lyrically rich fictionalised passages. By focussing equally on Kitchener's music as on his hitherto undocumented private and political life, Joseph gets to the heart of the man behind the music and the myth, reaching behind the sobriquet, to present a holistic portrait of the calypso icon.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ANTHONY JOSEPH

KITCH

A FICTIONAL BIOGRAPHY

OF A CALYPSO ICON

https://www.peepaltreepress.com/home

https://www.facebook.com/peepaltreepress

https://twitter.com/peepaltreepress

First published in Great Britain in 2018

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

© 2018 Anthony Joseph

ISBN13 Print: 9781845234195

ISBN13 Epub: 9781845234430

ISBN13 Mobi: 9781845234447

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form

without permission

CONTENTS

Part One: Bean

Part Two: Lord Kitchener

Part Three: The Grandmaster

Epilogue

Afterword

For my father

Albert Hugh Joseph

1943 - 2017

who was human, after all

KITCH

PART ONE: ‘BEAN’

1941-1947

He have melody like peas grain. — Lord Pretender

Everybody know ‘Kitch’ but few know ‘Bean’. Is he sister give him that name, because as a boy he was so tall and thin. She used to call him ‘String Bean’, ‘Bean’. Then some people, where he was living in Arima would call him ‘Bean Pamp’, because Daddy Pamp was he deceased father name. I used to call him it sometime, quietly, and he would laugh because he know that name dig far, the name is ‘Bean’. But I never prostitute it or let everybody know.

— Russell Henderson

GREEN FIG

THE STABLE HAND in his rubber boots throws a bucket of disinfectant into the pig pen. Then he brush it down. Sun coming up slow on the market now, but a faint moon still in the sky. Black back crapaud still weeping in the gullies, corn bird flying from vine to river vine. Is Saturday. Donkey cart and wagon wheel coming down the main road from Valencia and Toco, leaning in the potholes and the lumps in the road, coming to the market, heavy with purple dasheen and pumpkin, plump with green christophene and lettuce by the basket, long brown cassava and breadfruit, mauby bark, yamatuta. The knock-kneed dougla woman sets her stall by the market side, near where the road slopes down into tracks and rickety cratewood stalls. She stirs her cauldron of cow-heel soup and hums holiness hymns. She has been there since dew-wet morning, from the first glimpse of light burst. Her pot bubbles and spits and the scent of wild thyme and congo pepper drifts through the market like a spell. Soon, in the damp woody spaces of the covered market stall, chickens will be swung by their feet, to flutter against the grip of the abattoir man, with his cutlass hand and his hot water boiling on a fireside, to dip and pluck them beating, from wing and narrow bone. Morning opening like a promise above Arima.

Miss Daphne sits on an overturned iron bucket shelling pigeon peas in the market yard, with rose mangoes and speckled breadfruit laid out on a crocus sack before her. She speaks to the full woman selling navel orange in the stall beside her – reels her head back, laughs – and peas fall from her crotch. Down the aisle, Ma Yvette selling bottles of black-strap molasses, Ma Pearl selling saltfish, smoked herring, pigtail and garlic, Madame Hoyte have nutmeg and mauby bark, Mr Chambers selling lamp oil, Picton have corn. Customers walk now among the stalls, choosing okra and sweet peppers, cow-foot, tripe and live crabs for Sunday callaloo.

Later, in that afternoon time, after the market has been deserted, when only the stink of fowl-gut and rotten fruit remains in the gutters, and the traders are packing their unsold goods, a team of long cars will roll slowly across the ragged field behind the market. The dry season has parched the ground there till the earth is veined with fissures. Dust. Buicks, Austins and bullet-shaped Chryslers are taking French Creoles to the Santa Rosa race track for that afternoon’s races.

Up hill to the north, young Bean sit down on the worn wood of his front step with his head between his knees, making rhythm beat with a guava stick against the splintering edge and humming upright bass in the throat, comping with the high notes. Eileen, his sister, frying fish in batches in the outside kitchen behind the house. Bean could smell the flour and oil burning in the skillet. A bee start to inveigle the stick. Bean get up, dust off the seat of his pants, catch a vaps just so and walk down St Joseph Street, whistling, his slipper slapping the gravel. He wave to the hornerman Deacon sanding cedar crooksticks in his shed, he say hello to the black-tongued soucouyant hanging white sheets on a line flung between her lime and barbadine tree, to Baboolal the one armed tailor, needle in his mouth.

Crossing the main road, by the dial, he passes the market vendors dragging their carts home, then he walks across the dusty field beyond the market to the old Samaan tree near the paddock. Its branches spread over the wild yard where horses roam. He sits among its raised roots where a rage of ti-marie bush waits with leaves that shut to the touch. From where he sits he can see the jockeys walk their horses from the paddock to the races. He can smell the horse dung, hear boots kick dust. With his head resting on his forearm, and his forearm across his knees, he takes a stick and starts interfering the poor ti-marie bush. But is bass for a tune what humming in his head. He watching how the ants and batchaks live in that little jungle down there, between the picka bush. Each frond he touch folds like a shy shutting fan. It take him right there by the paddock and he didn’t even know it take him. One thing he thinking and another thing thinking behind, melody spring before the words reach the rim of his mouth, like something telling him each time what the next word or note would be, the song singing itself fully formed in his head, as if he had been working on this song even as he worked in the field that morning, even as he walked through the village at night and waved, stuttering to the hunters going uphill with flambeaux and lances, cocoa milk and cigarettes, black-back crapaud bleating in the bush.

He looks up through the diamond patterns of leaf and light, to see if the song has fallen from the saaman trees’ canopy. His lips move to whisper, his ears shut out all sound but the song. And not even the thoroughbred gallop along the dirt track with its high ass pumping, the splash of dust it kicking, not the whip or the rustle of savannah breeze through the leaves, or the announcer on his megaphone, or the sky-blue Buick engine’s roar can shift him from where he is.

Mary I am tired and disgust

doh boil no more fig for me breakfast

It come out whole. He never have to write it down. Gone back home now and have to keep it in his head, trap it in there, like a humming bird in a bottle, seal it in by repetition, stitch and tie it into creation.

1941: GASTON AUBREY

WHEN I FIRST SEE Kitchener is in Arima I see him.

My band used to play a lot in Arima and it had a dancehall upstairs the Portuguese laundry, right by the old racecourse, where they used to have christenings and wedding receptions. Was right there I used to play piano with Bertie Francis band, Castilians. We would play, a lil’ Count Basie, Glen Miller, calypso music. And after we done play we go looking for Chinese restaurant, for cutters, or the souse woman by the market.

Right by the dial there was a tailor shop, an’ sometimes, if you there in the day, you may see Kitch, always dressed well; he very tall, a good looking brown-skin fella, always with the open shirt an’ the neck tie, an’ he singing calypso.

The first tune I remember Kitchener singing was ‘Green Fig’. I see him sing that right in Arima, one evening, Carnival season, when he stand up under the dial, light on him, an’ he singing this song an’ people start to gather round. ‘Mary I am tired and disgust, doh boil no more fig for me breakfast.’

People calling ‘Kaiso! Kaiso!’ So he sing a next verse.

An’ when he finish he say, ‘Gus boy, I feel I going down town. I going down Port of Spain to m-m-m- go make my name. Arima eh have n-n-nothing for me.’

I watch him. I say, ‘Bean, town not easy, you feel you ready for town?’ He wasn’t Kitchener yet, he was ‘Bean’.

He say, ‘Yes, I ready.’

I say, ‘Well, if you need a piano man, ask for me when you reach down; I living Belmont Valley Road.’ An’ you know when that man reach in town he really come up Belmont and look for me. And is so we start to play music, from then, for years.

TOWN SAY

BEAN STANDING IN THE MORNING YARD under the kitchen window where the earth was slippery with mud from washbasin water, scent of stale soap, swill, and cow dung and frangipani in the fields. He washes his face in the enamel rainwater bowl, wrings and flicks the water from his hands. In the bedroom he combs his hair in front of the mirror. He wears the white shirt he has starched and ironed himself, the brown trilby, pinched in the peak, the school blue suit his father left behind, the one with the pants a lighter blue because his mother once washed the thing with coal tar soap on the river rocks and it faded. The black shoe cracked across the axle of the instep from walking long and hilly places.

While dew still drying, he leaves the wooden house on St Joseph Road with his grip and box guitar in a burlap sack, grease from two fried bake oozing grease through brown paper in his inside jacket. His sister watches him from the front door, as he crosses between the fowl shit and the mud and onto the government road. Bean turns back to wave, sees the house leaning to one side like it want to fall, the wood corroded, termite in the ceiling, wood bug in the rickety balustrade, and his sister stand up there silent and proper, reserved. But is gone Bean gone.

When the people of the village see Bean walking along the gravel road with his suitcase, they come to their fences to wave. Sister Mag stops from sweeping her yard to smile broad and whisper a prayer for Bean. The Deacon stop bulling he craft, to watch the young man go, and Pundit, who old, turn from throwing his bowl of rancid urine on the breadfruit tree root. ‘Bean boy, is you dress up like a hot boy so? This early morning, where you going? America?’

Bean grin like horse teeth, ‘Is town, in town I going.’

Bean walking the slow incline, remembering down what Lord Pretender tell him. ‘Good as you is,’ the younger veteran say, ‘you not really a calypsonian till you sing in Port of Spain. That is where the angle does bend, me boy, that is where real calypsonian does get born. You could win all them country champion, but you must, you must come in town.’

Down from the east through rustling villages, brisk with raw country on either side, and the black wavering line of the main road stretching out in the bright morning. Bean sit on a smooth wooden bench in the back of the rickety Darmanie bus, and six cents to town he gone rocking in the bounce and swinging tug, with his long mango head leaning against the window watching the sun cast its buzz across so much wild countryside.

D’Abadie

Tacarigua

Five Rivers

over iron bridges, through pasture land with churches hid in bush, a pink orphanage beside a river, the mint and white minaret of a mosque…

Arouca

Tunapuna

St Augustine

St Joseph

Mt D’Or

A wire-veined man sits in the seat across from Bean with reddened eyes that bulge in the leathered cage of his head. Two red fowl cocks caw and flutter in a wire cage between his knees. He wears raw brown linen trousers with frayed hems, a sky-blue shirt. His corns and mud-stained feet slip between rubber slippers. He shifts nervously, tapping his feet in some hidden rhythm. Bean lowers his gaze when the man turns towards him, then he catch the scar on the side of the man jaw. Entering the village of Champs Fleur, a song begin to compose itself in his head:

Pa pa dee, pa pa dee-o

Ah come from the country

Pa pa dee, pa pa dee-o

cock fight in the country

The man fowl cackle and cussing, but nobody will say anything. What you expect people to do? Bring complaint? And get cuss or badjohn beat them? But a middle-aged woman, sitting in the back, just wringing her wrinkled hands over the beaded purse on her knee. She wears a green lamé dress of her dry season menopause, patent leather court shoes, her feet shut at the ankles, church hat tilted on her head. When the chickens fuss and flutter and fowl shit start to funk up the bus, she put one dark gaze down heavy on the cock merchant, so he could feel the full weight of her stare, then she turn back, with the same pious gaze, suck her teeth to steups and summon a hymn.

Mt Lambert

Petit Bourg

Silver Mill

San Juan

The bus trembling, troubling the road. Bean, rocking between the fowl thief and the Adventist, leaning in the corner side the back seat with suitcase between his knees.

Barataria

Morvant

Laventille

These northern hills of Port of Spain, laden with wood-shacks and galvanize roofs, sparkle in the sun. Open sores of ghetto ravines. Slum wood. Hillside tenements where the heat burst like pepper in a pot. Driving down past the La Basse, on with its stinky sweet smell of black mud rotting in swamp land, and the rum and coconut oil factory, citrus scent, distilleries, and the sky extending out to brightness over Port of Spain, where human cargo spills out into the streets like ants from under a hessian sack of forgotten meat.

Policemen in white custodian helmets measure the traffic. Jay walkers and small-island market women stroll past carrying baskets on their heads. Walk a mile and a half. Bats in the garret of the big house, big men playing wappie there, slapping harsh cards down, and the drain in the abandoned land behind the barrack yard festering with thick black-blue love fly hissing, so the air there always have muscle. A dog licking salt from the edge of the world, in Marine Square where the tamarind trees grow high and wide, and black dravidian beggars stew in heat and piss at the roots.

Bean puts down his grip on Henry Street, letting the city rock him in its river of flesh and concrete. He not sure what to do. Not sure how to move. Road running left, road running right, and he now come to town on the Darmanie bus. He step to cross the people road and a jitney near bounce him; was a Yankee Willys jeep that pass and splash a puddle on him; US Navy. One stink puddle, funk up with rancid water and genk that run ’way from the Syrian steam laundry, wash up on his foot, like baptism in the city.

‘The Champion, boy!’ The voice startles him. This man, Mr Gary, waving, crossing the road towards him. Bean notices his wide bandy gait, like the curving limbs of a calliper, the unlit cigarette between the fingers of his right hand, and his voice pitched high and almost girlish, to cut through the noise of the street. Mr G puffing from the exertion of running behind the calypsonian, but he is the kind of man who seems to wear a permanent grin. ‘Where you going, Saga boy? I tell you wait for me by the bus depot and you walking like you know where you going?’ Extending a hand for Bean to shake, patting the young man’s shoulder at the same time. ‘Ha, you walking like a drake, like you know Port of Spain, but you don’t know town no arse.’ Now he laughs, his head slung back.

‘I just s-seeing what I could s-see. I thought maybe you did come and gone,’ Bean says.

‘If I say wait is to wait, man. How you mean? You feel you could just come from country and start perambulating up here? You want these vagabond rob you? Anyway…’ He lights a cigarette, whipping the match shut, then flinging the wick to the ground. ‘Come with me.’ But it is this word ‘perambulating’ that Bean considers as he follows Mr Gary through the mess of black shack alleys and thoroughfares that is eastern Port of Spain. Unfinished wooden houses, barrack yards. The promoter stops grinning at the corner of Observatory Street. ‘Now, champ, let me tell you from now,’ he says, ‘don’t think because I bring you down from the country it mean I have hotel room for you, eh. You eh make a red cent yet, much less to pay rent. Once you start working in the tents, you can rent bungalow, but for now you could stay in the Harpe.’

Bean turn. ‘La Cour Harpe? Is there you-you carrying me? I hear that place very terrible.’

Without turning to face Bean, Mr Gary says, ‘Don’t worry yourself, people does say it bad, but it not so bad in there.’

So they walk the slight incline up Observatory, cross a bridge, past the poor house and turn left into a yard, the entrance marked with a hand-painted wooden sign: La Cour Harpe. All this time Bean quiet, he just watching the yard; the Baptist flags in the far corner; the lush long zigar bush grown from the moist land near the latrines; the mud-walled bungalows; the sandy, snot-nosed children pitching marbles in the communal centre – kax, pax, patax – against their knuckles to punish; the young men knocking iron to music in the shade of a gru-gru bef tree; the laden belly of washing lines strung from shack to shack; the hot tin roofs and the rustling of leaves; the grief water stagnant and pungent in cesspools; the women sitting on front steps scandalising, with their dresses drawn down between the valley of their thighs; the fisherman returning from the sea with a bottle of English gin; a cacophony of whores; rats in the attic and the soldier van passing; panty wash running in the ravine; moss like phlegm on the ravine bed like strands of something blown by water.

In the far right corner of the yard, just before the abandoned land and the dry river running under the silver bridge, by the palm tree in a tenement garden, a brown pot-hound barks and rolls in the rugged dirt to scratch mange from its back, and a big-headed boy runs out from behind a barrack house in khaki short pants; the fly undone, barefooted and barebacked in the government sun, to see the Arima champion coming his come with the grip and the guitar, just reach from country, smelling of earth and perspiration, laying his grip down. Watch how he pushes his hat back with the wrist, water pouring from his head. Bean ’fraid to stutter, but he somersaulting in his skin, and Mr Gary, standing there next to the country singer, hands on hip, his gut puffing out, clears his throat and spits,

‘This a place they used to keep slave,’ he says, ‘and when the slave get free they stay living here. But these is good people here, is no problem if you live good with them, plenty calypsonian living here.’

Bean’s eyes widen, ‘It have calypsonian here? In this place…’

‘How you mean man? Is here self they does live. Attila pass through here – you must know that – even Lion, Lord Snail, The Growler. It have plenty music here, plenty bacchanal too, and woman, lord. You playing stupid, man; you must know about the Harpe.’

But looking around at the bright-lit chaos of the tenement yard, all the young calypsonian can see is a whole heap of ketch-arse shack what breaking down. That night, Gary find him keep in the house of a gap-teeth woman who living in a corner house with a crop of rancid children, make him a pallet on the floor. Country boy used to that. He used to bathing from a pan cup, he used to poor-folk ways, and latrine and moist bush in the elbows of the land. But that night he ventures out into the city alone. He walks along the perimeter of a great savannah, past the oyster vendors with flambeaux and green-pepper sauces burning, then down Frederick Street, sees night clubs and American soldiers leaning on bonnets outside brothels. Creole Jazz. A band somewhere, a cornet punching the dark; blue lights in lanterns in the Chinese restaurant.

The Arima Champion has entered Port of Spain.

Them days you couldn’t just say you coming to Port of Spain to sing calypso. You had to be a certain level, and you had to have a certain pedigree, you had to be awarded. So unless you were the champion of Arima you couldn’t come to Port of Spain. To sing calypso in Port of Spain you had to be the champ of Gasparillo, the champ of San Fernando, the champ of some place in Gran Cumuto and then they say, ‘Well, he’s Cumuto champ.’ So Cumuto champ will now have to beat Arima champ, and when you win champion of Arima, now you could come into Port of Spain.

— The Mighty Chalkdust

EUGENE WARREN, 1943

I REMEMBER KITCHENER when he land in La Cour Harpe. I was living with my grandmother in an upstairs house right there in the barrack yard, what you call the garret, the attic. We used to stay up there, not because we was well off, but because my grandmother, resourceful as she was, used to wash clothes and cook for the landlord. So because I living up there on the top, I look like a big boy to them fellas down in the barrack yard. But is rat and woodslave up there, red ants, termite like nuts. And the old lady had to wash the landlord big flannel pants and his drawers on a jooking board in the yard, starch and iron his shirts till she catch dry cough and ague sometimes, so it wasn’t nice. But even so we was better off than the people living in the yard; down there was pure ketch arse. The fellas used to call me Scholar because I could read and write, my head always in book, so them calypsonian who couldn’t write or spell good, like Melody, used to sing and get me to write their words out for them.

La Cour Harpe was a big yard, a courtyard. It had a big house by the entrance, where the landlord living, and we living upstairs. Below had a big gate that used to close at night. On the other side of the entrance it have a little drugstore, a lady selling food, maybe a shop selling groceries. You walk through the gate and in front you, in the centre, was an open space, the yard, gravel, it hard, where people used to lime and skylark, and on both side it have barrack room around. Some room small but divide in two, a back door, a couple slat window, a bench where to cook. It had a long grass space in the back of them rooms, it had two-three standpipe there, some latrines that everybody using. Everybody washing clothes and doing their business right there in the back. Is sewage there, is dirty water; it squalid.

So you want to know how a lady and a man, or a lady who don’t have no husband, living in one room with four and five children? Or how from tanty to uncle and grandmother living in one barrack, or how fifteen, sixteen Chinaman living in one room, paying six cents a night? That was La Cour Harpe. And that is where Kitchener come to ketch his black arse, to live hand-to-mouth, sleeping where he could find a hole, where jamette stooping to piss and stick man bursting each other head, right there in the barrack yard with everybody. Kitchener get to know the life, he get to know town life.

When them calypsonians come down to town they always end up living in the Harpe. But when I say living, I mean they only changing their clothes. Because, remember, soon as calypsonian wake up they have to go and hustle, they bound to go sing by some corner for a lil’ change or they never eat that day, they never pay rent. Unless, well, they have some woman minding them. So if something happen the night before, they sing about it the next day. Sometime they go by Lung Ting Lung shop on Henry Street to print lyrics so they could sell the copies on the street; penny a sheet.

When Kitchener come out he hole in the day – because he sleeping till 10 or 11 o’clock in the morning – he come and he take a bath, he change his clothes and he come out in the yard with his hand on his hip. He surveying Observatory Street like he build the road. But he have to hustle to eat that day, so he thinking what he could do, how he could get a few bob in his pocket, because he belly empty, rent must pay, he must maintain he image as a calypsonian. He would go by the corner of Henry and Prince Street. A Syrian fella name Moses had a bar there, and Moses would put out a plate with a few salt biscuits, a piece of roast saltfish and maybe a lil’ flask of rum on the table for them calypsonian, and they would sing. Men like Spoiler, Melody, Sir Galba and The Mighty Viking used to go there to find out what mark play in wappie game or how the hustle looking that particular day. As a boy I would stand up in front by the bar and listen to them sing. But they used to run me! They used to say, ‘Lil boy, move from here! What you doing here? You eh see is big men here. You mother know where you is?’

Because that’s one thing, they very respectable, always dress sharp, they wearing necktie, suspenders, shoes shine up, always in suit. All the big bards used to wear suit and tie, felt hat, two-tone brogues. They looking good, but they broken to thief. Them days it had no real money in calypso, unless your name is Roaring Lion, Caresser or Attila the Hun.

Sometimes Kitch used to sing at the corner of Prince and Charlotte Street. There was a Chinese restaurant there and he used stand up in front the restaurant and play guitar and sing. People pass and maybe give him a penny or two, maybe he sell two or three music sheet. And if you call him, ‘Ai Kitch,’ he turn round and he answer you, whoever you is.

‘Ai chief, wha’ going on?’

Well, eventually the Chinee people run him from outside there. They say he was obstructing. Another time I see him quite down on the wharf, singing for them stevedores. All that time he struggling. Sometime not one black cent in the man pocket; he hungering, but you would never know his business, you would never know that is one good pair of leather shoes he have that he polish; the suit he will wipe it down when it dirty. Sometimes he wear just the jacket with a khaki pants. Sometime he wear the suit pants with a white shirt and a tie. When things brown he borrow a jacket. But Kitch would never ply you with prayers when he see you, he wouldn’t moan. He hold his head high and he carry on, he make his kaiso and, joy or pain, he singing same way – white shirt and tie, he going up the road.

Up Frederick Street had a yard where tests used to go and lime, to listen to them bards old-talk and sing. I see Kitch there one, lean up under a tamarind tree, one foot up on the trunk, strumming his box guitar. He was composing ‘Tie Tongue Mopsy’, right there, in the dust blowing across from the savannah. And if you like it, maybe you give him a lil’ change. Kitch wasn’t no real hustler, he wouldn’t lock your neck, he wouldn’t thief, his whole intention was calypso – sun, rain, belly full or empty belly, is kaiso same way.

Is when he come Port of Spain, then everybody was saying this guy coming from Arima, the Arima Champion, the Green Fig man, and when we get to hear him, everybody say, ‘Well, this man is a genius, boy’. The words he used to bring, and the things he used to use in the calypso, was unbelievable. And the way he rhyme is like a story, every verse is different – it tell a story. And the words, his diction, and the way he used to put his story together, was incredible, y’know. Anywhere you see Kitch, you see me, anywhere he goes, I there. When he make a calypso, even before he know it, I know it! Because I could retain, you know. And he sing it and say, ‘This is a new one’, and he have the guitar and he humming it under the big tree in the Harpe, and he’d sing it for me and within minutes I have it a’ready; I have it a’ready and I singing one of Kitch new ones. When I start to sing calypso, I call myself Young Kitch. We was very close. He live in my mother yard in La Cour Harpe for a while. In those days he had nothing, in the hard days. So Ma had an oven there, a mud oven in the yard, and for a while he used to sleep up there, on top the oven.

— Leonard ‘Young Kitch’ Joseph

STEEL BAND BLUES

Nights in the Jungles of La Cour Harpe

THE RIPPLE OF STEEL CAME to Bean’s bed from the iron band beating there in the gap between wood shack and wire fence round Harpe yard. And the sound of the iron beating was Arima, and the sound of the beating was his father, Daddy Pamp, working the iron in the smitty, when iron red and melting till water make it rigid, and triplet notes would seep out from under the mallet and sing like a flute in his ear, and from the sound it making, everybody in the village would know that Pamp was in the fire-shed making iron bend.

Bean can’t remember when he started singing calypso, but he sure he been singing since Pamp used to send him to fetch water from the river near, and he hear the bamboo creak, the parakeets whistle, the bull-cow bawl, the silver fisheries flitting. After a while, everything will sound like music, and when he start to hear it, he sing along, till now he reach town, as man, and he dreaming in the early dawn of the ragged yard, beneath the starch mango tree that hover, with leaves to trouble him where he sleeping, quite on top of Ma Holder’s oven.

The sound from the iron band is not flung far from the blacksmith’s treble, nor the stick from the steel, nor the wrist from the rubber, or the palm from the goat skin. Bean, in dream sleep, composing melodies for iron band to play; rugged polyrhythms of call and response, lavways, belairs, toumblack and yanvalou – all the l’s. In this dream he walks a simple mile from the yard down town to Tamarind Square and by the time he reach there he done orchestrate the whole damn thing.

But Daddy Pamp son, the Arima Champion, can’t afford even a six-cents room in the yard, so he begging pallet on floor and couch, and his real zeal strain from singing on the corner of Park and Charlotte Street every afternoon for two cents and three – a little meal. Yes lord, life in the barrack yard hard-hard like banga seed heart, and his bed so bogus and crumple, and the holes he wrap in have tarpaulin, and his perspiration pungent like cat piss in his armpit. He pick a bad time to come to Port of Spain. War in Europe, Carnival ban, people getting lick with cat-o-nine tail for playing mas. But maintain. You have to sing your kaiso in the tents, and the tent full of people. And he young still. So he hold still in the darkness, with the chirp of crickets and the hoot-hoot of toads in the ravine, where sewer cream and panty wash staining the edges of the world, until his heart becomes heavy in his chest, and he shuts his eyes tight against despondency, so that only the sound of the young men beating their iron drums penetrates his sleep. The sound is sweet, and beat by beat it expanding; it grow so wide until within it he can hear the whole village bluesing in the steel, the whip-waist man, the long-stones man, the children crying, the rag-and-bottle man who smelling of lizard shit, the Grenadian mother so protective of her daughter she walking five miles from the Harpe to Cocorite with the young girl beside her, to work domestic for the doctor. He hear how she rock back her head and laugh through sorrow. He hearing each poor man’s cry in the steel; every weary woman moan, flesh on flesh; every ringhand slap and cuss and quarrel and shiver of flu; of sigh on open sigh; of thigh on crosscut thigh; a jamette’s gnashing tongue as she sparks cuss around her saga boys’ head – rent to pay and chicken to pluck, yard to sweep and police to beat, and the saga boy only sleeping like cat on the threadbare couch, with one leg up on the back rest, till he up and get dam vex and fed-up of the jamette mouth, and leap from the couch to flex his manhood, to fling on his hot shirt and swagger down to Tanty’s Cafe where the Mighty Spoiler holding the corner, drunk like a fish but singing a new calypso, before he head back south.

Nights in the barrack yards of Port of Spain. Stars bright like pin pricks in a cape flung against the darkness. Humble in the corner, the calypsonian lay there, humming bass in his throat.

Kitchener come to Port of Spain because he want to come to Port of Spain. Nobody eh make him come. Kitchener was living in La Cour Harpe. La Cour Harpe was prostitution. Was a old hole in the yard, there. But he couldn’t afford nothing better. Kitchener come to see if he could make a dollar. The first time I saw a woman underwear was on George Street. I see women sit down with their legs open wide, wide, as a boy in the 50s, so I know what Kitchener had in La Cour Harpe.

—The Mighty Chalkdust

‘BOYIE’ 1944

KITCH MAKE HE WAY. He didn’t look for trouble. He ketch he arse like everybody in the Harpe. But he was ambitious and he had talent. Them times calypsonian didn’t have no money. They singing in Carnival season, but when the season done they broken again. People used to call Kitch ‘Country Boy’ because he come from Arima, and them times, poor fella, he like a jumbie all about Port of Spain, trying to get a break. He hustling, he sleeping in hen house, whorehouse and all kinda kiss-me-arse place. But somehow he always decent; always suit and felt hat and two-tone brogues, paisley tie. And you don’t ask a man where he get his money from. But then he start, regular, to sing in the calypso tent and things start to get a bit more rosy for the scamp.

The first tent I know was right in the back of Nelson Street, and I living in George Street, so when they singing over there, I could peep over the wall and see them from where I there in the barrack yard. I would hear all them fellas – men like Kitchener, Spoiler, Attila, even Tiger, Pretender, Lord Melody, I see them sing right there.

At first was just galvanise and palm, sawdust on the ground, but then all them bourgeois people from St James and Maraval start coming to hear calypso. French creole inquisitive. Yankee soldiers coming quite from the base in Chaguaramas just to hear this thing, even Captain Cipriani in the tent, big dignitary and mayor there. So they put bench for people to sit down, and they start charging decent money to get in. Fellas selling nuts, sweet drink. Children couldn’t go in there, but being as I was living in the back of the tent, I get to hear them sing. Them days your mother don’t even want you to hear calypsonian sing. Much less to stand up and watch them in tent. Calypsonian was ostracise, together with the pan men. So if my mother, so-help-me-God, catch me beating iron, or if she find me by the fence watching them calypsonian, she would break a lime branch and bawl, ‘Ai boy, bring your arse from there now or I cut your tail!’ And I wouldn’t let her have to call me again.

Kitch come down from Arima hot! He feel he was the champ; he win all them country show and he like a zwill; he cutting. But it don’t work so. Even legend does lie. First time Kitch went to try he hand in the tent, they put him to sit down, they make he wait. His blood was hot, he had good songs, but he have to show respect, he have to pay dues. Eventually they give him a chance and he get by. Yes. Them days somebody had to bring you up, a elder bard, and if you don’t know the big boys, somebody have to like you, introduce you, they have to give you a good kaiso name, they have to throw some rum on your skull plate and coronate you.

TANTY TEA SHOP

TANTY TEA SHOP was for the vagabonds. Tanty Tea Shop was Duke and Piccadilly Street corner, right near Silver Dollar whore house. Tanty Tea Shop was famous for never closing. Tanty never wash the pot. The pot on the fire all the time and is corn beef and bread, or saltfish and bread – that’s what she selling – and coffee, cocoa, an’ she have fried bake and egg, cheese. Tanty like she come from B.G. or Suriname and she have some Indian in she. Dark-skinned, she head tie, she apron clean, she calve fat like pup, busy in the kitchen.

Tanty was the late night place for them jacket man and they woman to come. Even the Yankee soldiers used to leave the base quite in Chaguaramas and come by Tanty. That’s where the action was. Jamette skin up on the road with rum in dey hand making one set a noise. Ponce used to hang round that corner. All the boys used to lime there. You sit down there at night and big men talking, plenty hustle in the yard. Who playing card, who have rum, thing to smoke.

But Tanty shop wasn’t no real cafe, eh mister – you cyar sit down inside there – was just a wooden counter, the kitchen behind, and Tanty serving you right there. She would put a bench out front on the street so tests could sit and eat their sandwich and drink their coffee. And if you there late at night, after fete or after the tents close, you could see Kitchener and Lord Melody, Spoiler when they come there for their corned beef and bread after the calypso tent close. And if somebody have a guitar, you might get to hear the things they composing.

Tanty place burn down one Friday night and would you believe that by Monday them fellas was in town singing,

No tea by Tanty tonight

No tea by Tanty tonight

Tanty tea shop burn down…

CORONATION CALYPSO

Is Tiger give him his name

THE BARD STANDING THERE between the bamboo posts that holding up the back of the calypso tent. They call him Tiger. Growling Tiger. But what they calling tent is just a shed that thatch. Growling as he sucking orange after navel orange in that narrow yard behind the shallow wooden platform they calling the stage, where old knotty zigar bush that hard to kill does trouble the wire fence that separate the tent yard from the back of the Diamond Penny whore house on St Vincent Street. The Tiger face screw-up: green citrus rind biting the corners of his mouth, his eye squinting, spitting the slippery seeds. His mouth like cardboard box when it wet, and he folding the orange for juice to burst, and it sucking sweet.

Sans humanité.

As the calypsonians arrive, they gather there, behind the stage, by the trench where mosquito biting. Some tests drinking bush wine, some puffing clay pipe, some singing low, say they warming throat till the deep croon come in. The fiddler oiling his elbow with a nip of rum, the sax man sit down on an overturned pigtail bucket, sweetening his old horn, tapping on the pads, twisting the mouthpiece to the exact angle, puffing it, prepping it, sucking the reed. The horn hanging down like child foot between his legs. It get knock much and plenty lacquer crack out, gun brass, but sweet when it blow; is a good horn. The trumpet man stoop, pants’ hem reaching up his shin bone, and the seam sharp, and where the socks don’t reach, it hairy. He fingering the valves, polishing the bell. Blow.

Sans humanité.

Tiger turn from the darkness and watch young Bean talking with the other singers. He watching how Bean hard-blinking out his words, sputtering like his timing belt break. The young man tall, what they call lingae, bent from his waist to trouble the guitar man ear, say he humming song. And Tiger seeing this sideways, leaning forward so the damn orange juice don’t run on the good white shirt that his woman starch and press for him that afternoon. And from how the Tiger stand – the bandy knee, the one leg slight in front of the other, resting light on the sharp outside edge of his black derby shoes, you can see evidence of how Tiger used to box before he start to calypso. He ruggedy steep, muscle lean, his fists big like grapefruit and his face know war: scar sided, the grin lopsided, and the eyes – the eyes like flat stone skimming dirty river, only glancing, glancing. Yes, Tiger was worries in the ring. The Siparia Tiger. He would stand brazen against bigger men from Matelot and Cedros. Men with good-good pugilist pedigree, who chasing world title an’ thing, and Tiger would tear them and beat them like snake. Men like Kid Ram and Jungle Prince get beat up and down the island, till Tiger win the bantamweight title of 1929, in this colony,

Sans Humanité.

When Sa Gomes send the Tiger to New York in 1935 to record calypso with Attila the Hun and Beginner, and the big men sing their songs and it gone down in the appropriate time, and it come to Tiger time to record ‘Money is King’, the arranger, Felix Pacheco, get up from his swivel chair and bawl, ‘That is not music. Young man, you break all the laws of music, you can’t expect these musicians to play this primitive thing you compose. I can’t arrange this. I won’t.’ Tiger watch Pacheco, he watch him frankomen in his face, till all the blood drain out the Cuban eye, and his expression change. Tiger never say nothing, but he watching Pacheco from below, like when pugilist on stool waiting for the bell to ring, ready to stand up and fight, and his voice growl deep and it heartless,

‘Boss man, hear my cry. I come from quite Trinidad to record this calypso, and it bound to wax. I bound to sing it.’

And they say he was so sure that quick-quick Pacheco cry, ‘Come now, play it again, let me hear it. Maybe I did not hear it right the firs’ time… Ooh, it is good, yesmanitgoodman,’ he say, and he start to score and arrange the damn thing, and it is a classic in calypso. Hear the song the Tiger sing:

If a man have money today,

people do not care if he have cocobay.

He can commit murder and get off free,

and live in the Governor’s company.

But if you are poor, people will tell you ‘Shoo’,

and a dog is better than you.

An audience begin to gather on the wooden benches in front of the Victory tent stage, waiting for the music to start. Tiger watching the young man that Johnny Khan bring to sing in the tent. He hear about him. This country bookie who pants short in the ankle, who wearing a black jacket that look like St Joseph Road prostitute put together and buy for him because he never have no money; and you can’t say you singing in tent without jacket. Tiger watch good when the great Attila the Hun himself, walk up and ask the young man to sing, let him hear, and how the young man strain with a stutter to say, ‘R-r-right n-n-now?’ Attila had say, ‘Yes, sing it come. What key your song in?’

And the Arima Champion say, ‘R-r-r-r-r…R-r-r-r…’

Attila watch him with compassion and interrupt, ‘Ray minor you mean? Is in E?’

‘Yes, gi’ me in E.’

And Bean sing it. And the fiddle man stoop there in slips to catch the tune, and the bass man wood start to tremble like a woman leg. The country boy grinning, he know he have a good tune. He fling down two verse and Attila say, ‘OK, good, good, I want you go on second, before Invader.’