2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Youcanprint

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The drama of war that has always, traumatically, affected all the children of the earth; the story of a country involved in World War II, occupied first by the Germans and then by the Americans; the stories of so many people who, in the shadows, contributed to the establishment of democracy and freedom, which we enjoy today

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

INDEX

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

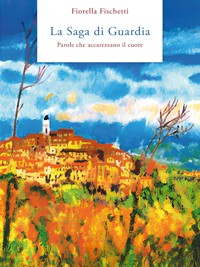

On the cover:

Antonio Pascale

Landscape of Guardia Lombardi (AV)

Oil on canvas

FOREWORD

by

Francesco Saverio Festa

(already Professor of History of the Political Philosofy at Salerno University)

A family memory approached with detachment, smoothly. Yet still they are family events at times dramatic, if not tragic, which also intersect the events of the Second World War, albeit with a sort of back and forth in an anti-chronological sense, but nice for the way the story's proposed.

It is an enjoyable reading, at times even amusing, thanks to the original strategy of using a disenchanted memory, to the point often appearing detached from the narrated events themselves.

The author is well aware that in order to propose her personal circumstances to others, acquaintances or not, there was no other method than a sort of sensitive mediation, capable to let others understand the story of a little Apennine community in the face of an entire Country plunged into a war adventure, almost grotesque: a small Italy madly inserted in a clash among giants.

A Country, often on the verge of economic collapse, which has never shone for warlike virtues, being endemically refractory, except for some minorities, to all sorts of bellicose initiatives.

In this respect I will never forget what an author, who's also privileged by the writer in her work, wrote many years ago in "War without hate", a book belonging to my father, which impressed me a lot as a child.

The author, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, sent to Libya to resurrect the fortunes of the italian army routed by the british armored cars, narrates that once an italian soldier confessed to him: "We are not inclined to war, you Germans do it better, while instead we deal with bridges and roads construction to facilitate you".

Rommel, surprised by this externalization, dedicates three pages to explain that the italian soldier is anything but cowardly or incapable, when well equipped and well guided by his officers.

"Is it possible that in the italian army there is a canteen for soldiers, one for corporals, one for sub officers, one for junior officers and one for senior officers, and finally one for generals? I consume the meal, often standing among my men, living their lives; only in this way, in fact, I would be able to ask them to risk their life for their homeland".

It is the mirror of a Country thrown into an epochal adventure without any authentic national unity spirit. The affair of Guardia de' Lombardi, the Apennine village described by the author, is the saga of a community and of a land that survives the disaster by relying on what more than any other, over the centuries, has cemented this "union sacreé" among the inhabitants, that gave the power to survive wars, as well as earthquakes: the community spirit.

In this context, the private events of a single family appear, after all, similar to those of many other local families, so a sense of measure and moderation is needed in narrating, in order to be welcomed, to interest others, to involve and tell them: it is a fresco representing the life of the village, my story is your story.

Did all this, perhaps, happen without the author having ever attended a course to write memoirs, of the kind that has recently spread so widely in our Country?

The Saga of Guardia

Words that caress the heart

To my father who has instilled in me the love of reading and my mother that of nature

Guardia stands on a rock

Carried by the millennia,

With its murky past,

to which the ancient wall

Of a castle that towers above

all the inhabited area.

Soaring to the sky is the bell tower

And an aged and weary mulberry tree,

to which each year a thousand

A thousand rounds of swifts

With the garrulous screech,

Which delight brings to the heart.

Chapter I

In the ancestral home

Only spiders reign supreme.

The somber, cadenced footsteps of the patrol rumbled, on the pavement, from one end of Via Celso to the other and reached straight to my childlike ears.

My heart beat wildly with fear. I hid my face in my mother’s arms, who held me so tightly that it almost took my breath away; I would have died of pain if any of those monsters with helmets, boots and a rifle slung over my shoulder had separated me from her.

There were Germans everywhere: in the streets, in the woods, in the mountains; they were swarming, shuttling on motorcycles between Guardia and Sant'Angelo, where the headquarters were. They requisitioned provisions and everything they needed. The soldiers, in order to get rid of the dust and seek relief from the summer heat, bathed naked in the wash-house at the Tolle fountain; they splashed in the 'ice-cold water and played with each other to splash each other in the face, they felt safe from the American raids, protected by the thick forest of chestnut trees, whose branches came down to lap the spring that gushed clear, suddenly, from the roots of the trees. One day, there was a knock on my Uncle Joseph's door; in the house was only my little cousin Ada, who huddled in a corner and did not open it; the soldiers began with the butts of their rifles to bang on the wooden doors; someone alerted my uncle, who rushed in with keys in hand: he let them in, and they, red with anger, loaded a table on their shoulders and left, after making a tour of all the rooms. They attributed their defeats in North Africa exclusively to the Italians, to their unpreparedness and to the lack of fuel that had not arrived in time, forgetting the sabotage by British, their radar and their Shermans built to travel on the desert sand; they considered us their poor allies to be treated with condescension. They addressed my father with deference only because he was an officer who had came back home broken and stitched up, but they enjoyed telling him:

- You are repatriated only because of our air force that has hunted the Greeks from the mountains.

There was dead silence in the house; the electricity had been cut off and my father, who had just lit an ancient Roman oil lamp, stood in the middle of the dining room ordering everyone to be quiet, to close the windows and balconies tightly so that the light would not filter out during the curfew hours.

My sister, after greedily having sucked down an entire bottle of milk, slept placidly in the large cradle, topped by a golden brass snake that once held a tulle veil, where all my ancestors had slept. She never threw a tantrum, growing white and red like an apple.

Often I plucked the bottle from her mouth and before my mother could stop me, I had drained all the milk, while my little sister laughed, thinking of a game that was repeated. She was born in Guardia Lombardi at the height of the war, with the help of a sinewy midwife with two big hands, attached to two wrestler's wrists.

My mother was terrified at the idea to give her birth at home, as I was born in Rome, instead, in Villa Pampersi, in Via degli Scipioni, assisted by specialized doctors and nurses.

I arrived in Guardia at the age of two, but I sucked the sap from it, which continues to snake through my veins and reflects the strong and rough character of those people.

Donna Filomena, a dark-skinned big woman with laughing eyes and an appealing smile, had a pot of 'hot water, towels, soap prepared and tried to cheer up my mother who, in pain, squirmed on the bed, moaning:

- At least my spouse was there; instead he was at the front and I alone to unravel with two children.

The whole house was in turmoil; Uncle Paul said to his sister Angela:

- Take care.

My aunt, who had given birth to five children at home, tried to calm him down:

- Don't worry, everything will be fine.

My sister was born without difficulty, but since my mother having had a mastitis with a fever at forty, she was weaned prematurely and raised on goat's milk.

It seemed that my father was not afraid of anything; his mere presence calmed us.

He had been born big, viscous and blue-eyed after Grandma had flown from the loggia about twenty feet high, losing her balance: her wide skirt had opened like a parachute and she had glided gently to the ground.

They had named him Umberto, eighth of eleven children, in homage to Umberto I of Savoy, his grandfather being mayor of Guardia.

His grandfather, a law student in Neaples, had given up his studies after the death of his brother Paolo, who was majoring in medicine, and had returned to Guardia to take care of his immense estates that extended till Andretta, from contrada Papaloia, so-called from “loia”, left by Pope Leo IX in 1053 in the clash with the troops of Robert Guiscard, who, before taking him prisoner, apparently suffered a defeat there.

The Pope, who later became St. Leo, according to the account of the peasants, having an army inferior in numbers to the enemy's, addressed a prayer to the Lord to help him at that juncture: a swarm of gnats suddenly appeared, blinded the enemies, and the papal troops prevailed (li muschilli cecarono li Nurmanni).

Frederick II of Swabia, having inherited all of southern Italy from his mother Constance D'Altavilla and Germany from his father Henry VI, had forfeited the (1) fief of Guardia Lombardi upon the death of Raone of Balbano, who lacked direct heirs, to donate it to Manfredi, his natural son, who was resoundingly betrayed by the Guardiesi, who promised him aid, which they never gave him.