Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

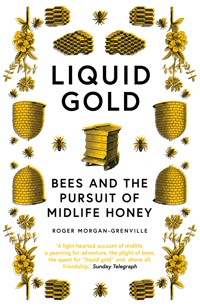

'This delightful memoir is an inspiring account of changing direction in mid-life, and a passionate plea on behalf of the honeybee.' Daily Mail 'A light-hearted account of midlife, a yearning for adventure, the plight of bees, the quest for "liquid gold" and, above all, friendship.' Sunday Telegraph After a chance meeting in the pub, Roger Morgan-Grenville and his friend Duncan decide to take up beekeeping. Their enthusiasm matched only by their ignorance, they are pitched into an arcane world of unexpected challenges. Coping with many setbacks along the way, they manage to create a colony of beehives, finishing two years later with more honey than anyone knows what to do with. By standing back from their normal lives and working with the cycle of the seasons, they emerge with a new-found understanding of nature and a respect for the honeybee and the threats it faces. Wryly humorous and surprisingly moving, Liquid Gold is the story of a friendship between two unlikely men at very different stages of their lives. It is also an uplifting account of the author's own midlife journey: coming to terms with an empty nest, getting older, looking for something new. 'A great book. Painstakingly researched, but humorous, sensitive and full of wisdom.' Chris Stewart, author of Driving Over Lemons 'Beekeeping builds from lark to revelation in this carefully observed story of midlife friendship. Filled with humour and surprising insight, Liquid Gold is as richly rewarding as its namesake. Highly recommended.' - Thor Hanson, author of Buzz: The Nature and Necessity of Bees

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 321

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Praise for Liquid Gold

‘A great book. Painstakingly researched, but humorous, sensitive and full of wisdom. I’m on the verge of getting some bees as a consequence of reading the book.’

Chris Stewart, author of Driving Over Lemons

‘Beekeeping builds from lark to revelation in this carefully observed story of midlife friendship. Filled with humour and surprising insight, Liquid Gold is as richly rewarding as its namesake. Highly recommended.’

Thor Hanson, author of Buzz: The Nature and Necessity of Bees

‘Liquid Gold is a book that ignites joy and warmth through a layered and honest appraisal of beekeeping. Roger Morgan-Grenville deftly brings to the fore the fascinating life of bees but he also presents in touching and amusing anecdotes the mind-bending complexities and frustrations of getting honey from them. But like any well-told story from time immemorial, he weaves throughout a silken thread, a personal narrative that is at once self-effacing, honest and very human. In this book you will not only meet the wonder of bees but the human behind the words.’

Mary Colwell, author of Curlew Moonii

iii

ix

To my parents, who gave me so many opportunities to love nature.

CONTENTS

DISCLAIMER

Beekeeping has inherent risks due to the toxicity of bee stings. If you are stung by a bee and experience symptoms such as difficulty in breathing, swelling of the tongue and throat, and/or a weak, rapid pulse, or you feel unwell in any way, seek immediate medical advice. Any adverse reaction to a bee sting, or multiple bee stings, should be taken seriously and referred to a medical professional before continuing with beekeeping activities.

The contents of this book do not constitute professional advice on beekeeping. Neither the author nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage allegedly arising from any information or suggestion contained in this book.

A NOTE ON NAMES

Some of the names of people, places and organisations in this book have been changed to protect their privacy and anonymity, and to avoid invading the quiet spaces of people doing what is essentially a peaceful hobby.

PROLOGUE

1969

He was called Mr Fowler.

Like most children then, I lived in a world devoid of adult first names, and so Mr Fowler he stayed. And when I thought of him, I really only thought of him as Mr McGregor in Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit. All I remember about him now is that he had a flat cap that he never took off, and a pipe that he never took out of his mouth.

He gardened for my grandfather, which must have been no mean feat, as my grandfather was a formidable gardener himself. One midsummer afternoon, while I was staying, I tiptoed round to the greenhouse to help myself to a couple of his Gardener’s Delight tomatoes while no one was looking, only to find that Mr Fowler was looking. He was there in the shadows, operating the antique watering system, but he was forgiving enough to hand me a couple to try, anyway. Perfectly did he understand the elemental pleasure of the smell and taste of an old-fashioned tomato straight off the vine in a hot greenhouse. For a minute or two, he stood with me watching a bee hard at work on the flowers above.xii

‘Why’s it doing that?’ I asked him as it darted from flower to flower as if its life depended on it.

‘It’s not an “it”,’ he said sternly. ‘It’s a she. And she’s foraging. She’s collecting pollen and nectar to take back to the hive to turn into honey.’

‘How does she do that?’ I asked, chastened. In the monochrome world of 1960s food, honey was something I actually liked and could easily identify with.

‘With a lot of help from her friends,’ he answered, and went back to his work on the stirrup pump. He wasn’t paid to entertain nine-year-old boys.

Mr Fowler kept a hive himself, in his little plot a couple of miles away. At some stage, he must have spoken to my grandfather about my furtive visit to the greenhouse, as the next time I went round, the latter announced that I had been invited over to the Fowlers’ for tea, and that I would be shown the hive if I was very good and said please and thank you to Mrs Fowler at all the right times.

So, when he had finished his day’s work, Mr Fowler and I bundled wordlessly back through the shady chestnut lane in his pale green Hillman Imp. As soon as we arrived at his cottage he became as light and frivolous as he had been stern and grave in my grandparents’ garden, as if the act of removing his hat and revealing the previously unseen bald head had lifted all formality from him. He and Mrs Fowler fussed over me like the sweet old people I’d only ever read about in Enid Blyton books, plying me with sandwiches, cake and xiiilemonade, telling me that I would never grow to be a big lad unless I kept eating and eating. At length, Mr Fowler put his hat back on and led me down the side of his tiny garden, to a spot by a bank on the edge of the neighbouring farmland.

‘There you are,’ he said. ‘That’s a beehive. Do you want to look inside it?’

I wasn’t entirely sure that I did, now that I was close up. But, after that huge tea and with a modicum of childish intuition, I understood that ‘no’ wasn’t on the menu of acceptable answers.

‘Oh, yes please!’ I said.

So he went back to his shed and brought out two faded white hats with veils attached, and a single pair of gloves. Having got my hat on, and with my veil securely tucked into the top of my sweater, and my trousers stuffed into my boots, I was still alarmed that he had only one pair of gloves.

‘A proper beekeeper doesn’t use gloves,’ he said, beaming. ‘He needs to feel how the bees are behaving, and he can’t do that through leather, or even cotton. Here, these are for you. Shall we open it up now?’

He lit a little bee smoker, and directed a few puffs into the hole at the bottom of the hive.

‘Why do you do that?’ I asked, sniffing at the wreaths of burned cardboard smoke that filtered up into the summer air.

‘That just calms them,’ he explained.

I’m not sure what I was expecting to see as he took the roof off the hive and laid it carefully on the ground – but, for xiva second or two, I was close to sheer panic. I had never seen so many living things in one place, so pulsating with hidden energy, and so densely packed. The impression of a chaos so much vaster than me made me slightly nauseous. The top of the open box revealed a moving carpet of bees, writhing this way and that, and rising and falling. I had recently read T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone, and all I knew about insects came from the few pages when Merlin turns Wart into an ant, and that had frightened rather than helped. A few bees flew at my veil, and I could hear the angry buzz of their wings, beating 200 times to the second. I had been stung by bees before, and the multiplied thought that there were maybe 50,000 of them in this box brought me up short for a second or two. I drew back a couple of paces, scared of being seen to be scared, but wary of being too close.

‘Don’t worry about the bees,’ said Mr Fowler, taking two smaller boxes off the big one at the bottom. ‘If you keep calm, they won’t bother you. And anyway, you’re well protected.’

With his bare hands and a prong from his gardener’s penknife, he levered the frames free from where wax and honey had stuck them to the box, and showed them to me as he took each one out to inspect it. I watched a few bees crawling across the backs of his hands, and wondered if he, too, was a bit nervous but just didn’t want to show it to a boy like me. Pointing at how the queen had laid eggs all around the drawn-out wax foundation, he showed me the difference between new brood and sealed brood, and explained what xvthe significance of each was. On the fourth or fifth frame, he said excitedly:

‘Look! There she is! There’s our queen!’ And, where he was pointing, squirming her way through a seething mass of bees around her was, indeed, one that was nearly twice the size and marked with a big red dot on her back. When I asked him how many queens there were in the hive, he said: ‘Only one! Just like Her Majesty in London. Just the one.’

‘But there’s no honey,’ I said. Honey was really why I was here.

He had been waiting for the question. ‘That’s because most of the honey’s in the smaller boxes. Don’t worry, we’ll have a look when we’ve finished inspecting this one.’

‘Why’s there no honey in the big box?’ I asked, and he said patiently that there was a bit, but that this was a lesson for another day.

Once the last frame was back in the box, he laid the first smaller box back on top of it, and pulled out a frame from that one to show me. It was glistening with honey, rich, golden honey in every available nook and cranny, as far as I could see. He handed the frame to me and asked me with a serious expression whether I thought we were ready for the harvest.

‘Oh yes!’ I said. ‘I think we’re ready.’

‘Well, I’ll tell you what. When you next come and see your grandpa, be sure he tells me that you’re coming. Then you can come here as well and help me take the honey.’xvi

After a few more minutes, he reassembled the component parts and closed up the hive.

‘What will the bees do if we take all their honey? Isn’t it what keeps them alive in the winter?’

He explained briefly that he gave them other food like sugar syrup, and that they were happy enough with that.

‘I wouldn’t be happy if you took away all my honey and just gave me sugar. Not at all.’ A tiny and indignant part of me was fighting for the bees, and he surprised me by saying quietly that perhaps I had a point.

‘Think you could make a beekeeper?’ he asked, as we walked the path back to his house, where my grandfather had recently arrived and was talking to Mrs Fowler.

‘Oh yes!’ I said. But it was more to show enthusiasm for a pot of his honey than any wish to be involved again with that maelstrom of uncontrolled energy inside a hive. Boys of nine don’t easily understand when they are being honoured.

‘Don’t forget to come again!’ he called out to us as we drove away.

But I never did. The summer became autumn, and the autumn became a new year that brought with it different enthusiasms, coupled with the wish to share them with boys of my own age rather than old countrymen like Mr Fowler.

Anyway, within a year he was cold in the clay himself, taken in his garden one sunny afternoon by a heart attack, and it was too late to ask.

I like to think he was with his bees at the end.

1

THE BEGINNINGS

May

I believe that life is chaotic, a jumble of accidents, ambitions, misconceptions, bold intentions, lazy happenstances and unintended consequences, yet I also believe that there are connections that illuminate our world, revealing its endless mystery and wonder.

David Maraniss

It was a windy day in May, with heavy showers running along the line of the South Downs.

Lunch was over, the coffee drunk, and we were wondering whether to offer to help wash up or just to head home and let our friends get on with it. The idea had originally 2been for the four of us to go for a walk with the dogs in the afternoon, but the appetite for it had been washed away by the regular rain. I saw Jim standing by the window, staring out across the garden into the field beyond.

‘That’s the third this week,’ he said, almost under his breath.

‘Third what?’

He seemed momentarily surprised by the question. ‘Third swarm of bees,’ he said. ‘I don’t think I saw a single one last year, but this time they’re everywhere.’

I joined him at the window, and looked out at what appeared to be a rugby ball hanging off a low branch of a nearby cedar tree. I had seen bees swarming before, but I had never really noticed a swarm settling like this. Jim said it was smaller than the two he had seen earlier in the week, and that it would probably soon be gone.

‘Where do they come from?’ I asked.

‘Could be anywhere.’ But he explained that their neighbour had kept two hives in his garden for years, and that he had left his wife a few months before, and there was probably no one looking after them any more.

‘It might be them,’ he said. ‘Equally, they are rather more likely to be from a wild colony somewhere deep in a hollowed-out tree, or up in the gap behind the eaves of a building. This is just what they do.’

It had never really occurred to me to wonder what bees did, or why they did it. I had once seen into a glass-backed 3hive in a local museum when I was a child, but I had long since forgotten whatever I had learned there. And, of course, I had seen Mr Fowler’s bees, although that was nearly half a century ago: 500 generations of honeybees would have come and gone since then. Nowadays, I only saw bees buzzing from plant to plant in my garden. I also read articles about the decline in their numbers, and what would happen to us all if their numbers fell below a certain tipping point.

‘Swarming is the only way they can reproduce their colonies.’ We were still staring out of the window at the dark lump hanging off the cedar. ‘Basically, they are only meant to have one queen until, one day, something tells the workers to create another one. That’s where it all starts.’

‘How do you know all this?’ I asked. This was as talkative as he ever got. Normally, Jim’s style was to just sit and listen to the noise of the world around him.

‘Oh, I kept a couple of hives for years. Ever since I was a boy, actually. Found them on the farm when we moved in, and got them going again.’ He told me that he had given up only when they had discovered that one of their young children had developed an allergic reaction to bee stings, and to continue with the hobby would just be tempting fate. One of the hives had already been empty, and he had given the other one away, complete with its contents, to a teacher at the local primary school.

‘I think there’s a number we’re meant to call for the local beekeepers’ association, so that one of them comes and takes the swarm. That way, you get rid of the bees, and they get a 4brand-new colony for free. But I reckon they’ll be gone soon, so I’ll just leave them to it.’

‘Why don’t I take them?’

I can’t remember actually saying it, but Jim assures me I did. For at least the next eighteen months, I would ask myself from which part of my brain that comment had come.

‘You haven’t got the kit, and you wouldn’t know what to do with it if you did. Apart from that, there’s nothing to stop you.’ He continued to gaze out at the swarming bees in his garden.

Then after a while, and with no further prompting from me, he said: ‘I suppose we could just take it, and see what happened.’

So we went out across Jim’s small farmyard to a shed that was full of terracotta flowerpots and old rolls of chicken wire, and found the redundant beekeeping kit high up on a wide shelf in the far, dark corner.

‘Look!’ he said, beaming with pleasure, ‘My old beekeeping suit.’ Every variety of British moth seemed to have had a go at it in the years it had been up there but it was still just about recognisable as the top half of a bee suit with an inbuilt veil. Then he chucked down some gloves, a filthy old sheet and a strangely shaped steel tool with flakes of yellow paint on it. It was a barn – indeed it was a farm – where stuff arrived and never left.

‘Have you got a smoker?’ I remembered Mr Fowler all those years ago, and that smell of burning cardboard.5

‘Not needed. Once we get a strong cardboard box and some clippers, we’re done,’ he said, and led me back out into the drizzle to collect his old hive and put it, disassembled, into the boot of my car.

‘But there’s two of us, and we only have one suit,’ I complained, as we approached the bees. In my mind’s eye, I was going to be the one who stood back and offered encouraging words from a safe distance. This was a job for experts.

‘I never said that I would do it, only that I would enable you to do it. It’s your show, but once you’re down there it will be a piece of cake. And anyway, swarming bees are incredibly docile, as they aren’t defending their honey.’ He looked rather pleased with himself at this observation.

A few yards from the tree, I put on the bee suit, which smelled of old paint and decay, tucked my trousers into my socks and listened to his explanation of how to go about it.

‘It’s simple. Get the bees off that branch by cutting it, and get them into the box. So long as you have the queen, the others will follow after a few minutes. If you’re still missing loads of them, just put the box upside down with a small gap at the bottom of one side so that the absentees can come in. Then wrap the box up with the sheet, knot it, and go home.’

‘Wouldn’t it be easier if you did it this time round?’ I was suddenly regretting the wine I had drunk at lunch, and the ridiculous idea that I could become an opportunist beekeeper. This needed the professionals.6

‘I’ve never done it before either,’ said Jim, explaining that he had seen it done, and felt that this should be quite sufficient briefing for me to proceed. His place was watching from the dry, warm kitchen with his hands round a large mug of tea.

‘But apparently it’s all about smell,’ he added, as he headed back up to the house.

So there I was in a wet field on a Sunday afternoon, half-protected by a beekeeping suit that was riddled with holes, and armed with a damp cardboard box, a dust sheet, and a pair of secateurs. I glanced back at the kitchen window where Jim had taken up residence once again. He had been joined by his wife and mine, the latter looking disappointingly unconcerned.

Only some months later did it start to dawn on me just how I had arrived in that wet field, how such tiny substitutions of unplanned adventure had tended to seep into a middle life that had become, in itself, all too planned. Where Jim had seen a swarm of bees hanging off the lower branches of a cedar tree as a little feature of natural history, I had seen it simply as an opportunity, something new in a life that had too little new in it, something a tiny bit risky in a life predominantly safe. I had no real intention of doing anything more than seeing if I could take a swarm of bees 7without instruction. Mine was an intervention that had no plan beyond walking into a large group of stinging insects and seeing what happened.

The swarm and I watched each other from a suitable distance for a while, a handful of bees flying over curiously to check me out. Step by step I approached the cedar tree and, as I got nearer, I realised that two things were wrong. First, the branch was far too thick for the secateurs to cut through; and, secondly, that I really didn’t have the faintest clue about what was going to happen. I stretched my gloved hand up to the top of the mass of the swarm and, for a moment, it seemed Jim was right: beyond a little local agitation, they really didn’t appear to mind me being around. Everything depended on what I did next.

In the textbooks, what I did next should probably not have been accidentally to drop the secateurs into the middle of the swarm while I was trying to hack away at the branch. About 25,000 bees rose angrily up in the air, and I got my first sting of the afternoon for my troubles, before they settled back around the branch again. My sweater had become untucked from the glove on the left hand, and a quarter of an inch is plenty of available skin for Apis mellifera to home in on. I wanted to rub my hand, but I wanted more not to give the audience any idea that the operation wasn’t going perfectly. I looked up at the window and saw Jim bringing his right fist down into his cupped left hand, and worked out after a bit that he was suggesting I just bashed 8the whole lot of them off the branch and into the box below.

When I first tried this, a disappointingly small percentage of the bees fell off the branch and into the box, and the violence of the action only led them to become angrier and more active. However, it also meant that I was by now fully committed, and so I hurriedly started to brush swathes of bees into the box with my forearm. It wasn’t perfect, but after a minute or so I had more bees inside the box than outside, with the rest of the swarm flying angrily around me. It wasn’t what I had envisaged at the outset, but it was just about possible to imagine that I could have them all settled in another quarter of an hour. I carefully put the box on the unfolded sheet on the damp grass, turned it upside down and wedged a small stick under one side to leave a gap for the others to come in. Everything now depended on whether I had got the queen on the first run. If I had, they would come; if I hadn’t, then it was all over.

While I was watching, and starting to realise with a measure of satisfaction that the direction of travel was into the box, not out of it, I also noticed that I was no longer alone in my veil. Two bees had joined me inside it, a fact I worked out by being able to see their backs, rather than their undersides. This is not a good feeling for any beekeeper, and it seemed pretty obvious that it wasn’t going to end well for either me or my new friends. The fact that I couldn’t see how they had got in indicated that I therefore wouldn’t be able to find a 9way of getting them out, and so I just got on with what I was doing, and waited for the inevitable. Sting number two, when it came, was on my scalp, and sting number three followed shortly afterwards on the side of my neck. Idly, my brain, part of which was involved in starting to close up the box now that the flow of bees into it was drying up, was calculating the time it would take to drive down to the Accident & Emergency department at St Richard’s Hospital on a wet Sunday afternoon, if it all went wrong.

An early word on stings.

Two things, unfortunately, define bees in the mind of the disinterested observer: honey and being stung. From earliest childhood, our minds are allowed to bundle the honeybee into a huge category of annoying and potentially dangerous insects that we should avoid, and consequently not care about. This mindset has a profound effect on our attitude to them through childhood and beyond, a situation that has not worked to the bee’s advantage.

Bees are passive creatures, and only sting when their hive or honey is threatened, or if they are being roughly handled. Most bees die after stinging a human (the barbed sting is ripped away along with half her abdomen as she flies off), so it is not an action that nature encourages them to do other than in extremis.10

Beekeepers, even the very best ones, will get stung from time to time. They just will. So long as the actual sting is removed without delay, the pain, which is a result of the apitoxin that has been injected, will subside reasonably quickly, and the swelling within 24 hours. You can take your pick from a thousand traditional cures for a sting, including garlic, copper, toothpaste and prayer, but I have found that time, plus anything with benzocaine in it, kills off the pain. The one old wives’ tale I have found to be completely true, is that the melittin within the sting has a short-lived, but nonetheless profound, effect on stiff joints in the area of the sting; unsurprisingly, Californians now pay a great deal of money to get themselves stung. In both senses of the word. To be fair, if a bee were taking part in this conversation, she would add that their produce arguably offers ten health benefits for humans to the one disadvantage they themselves bring. These run from protection against cancer to sugar regulation, anti-bacterial effects, skin care and sorting out coughs, and there is some evidence to back these up. However, there is a lot more evidence to suggest that you should avoid getting stung when you can.

A very small percentage of people develop a hypersensitivity after one sting which can lead to a severe anaphylactic shock when stung again later. This is one of the main reasons that many beekeepers give up the hobby, and therefore it is also a more than adequate source of cheap second-hand equipment on eBay. Most beekeepers await the first sting of 11a new season with keen interest, as that is the one that will likely reveal if any sensitivity within their bodies has changed.

Over time, I have come to regard a successful season as one where pots of honey harvested outnumber stings received by a factor of twelve to one, or better.

But back on that wet Sunday in May, I knew nothing about bee stings other than that they hurt, and that they prevented me from getting on with what I was trying to achieve. It had probably been half an hour since I had first approached the swarm, but there was now only sporadic activity around the box, and a quiet if rather sinister hum coming from within it. I decided that this was as good as it was going to get, and carefully wrapped the box in the sheet before knotting it up and carrying it back to my car. I allowed myself a faint pulse of pride for not entirely messing this up. I may well have been soaked, dirty and in pain, but I had also kick-started a new adventure, however short it might turn out to be – and new adventures, I was to discover, are the tiny building blocks of middle life.

It took a little bit of persuasion to get Jim to temporarily part with all his beekeeping kit, and rather more to get Caroline to climb into a car that now contained up to 30,000 new house guests.

‘You’ll be fine. They’re in a box, in a sheet, knotted up and completely safe.’12

‘But what are you going to do with them when you get them home?’ she asked.

Caroline is a graduate in physiology, an achievement that combines with her natural persistence to give her an unfortunate habit of asking practical questions at inconvenient times.

‘I have a plan,’ I replied, as if my secret confidence settled the matter. I didn’t tell her that my plan simply consisted of doing an internet search on ‘what to do with 30,000 bees’ and then following whatever instruction it gave. I also didn’t tell her, of more immediate concern, that I had spotted two or three bees rising up in the rear-view mirror, where they definitely should not have been. I opened the windows in the hope that the rush of air would pin them against the back windscreen and leave them undetected.

‘Can we stop for some milk?’ she asked, as we drove through the local town.

‘I’ll nip back and get some later,’ I said.

‘But why not do it now, while we’re outside the shop?’

I looked nervously in the mirror, where a few more bees had emerged. Knowing that things could get quite awkward quite quickly, I said something about the bees needing to be settled down as soon as possible, and stamped on the accelerator for the five-mile journey home. By the time we got there, there were possibly 30 bees flying around the box in the back of the car, looking for all the world like latecomers to a rock festival.13

Garbage in, as they say, garbage out.

The quality of the answer that you get from a search engine depends entirely on the question you pose in the first place. Having secured the box of bees with a tighter knot, and left it in the shelter of the porch, I went to my computer and asked it ‘how to rehome a swarm of bees’. The subsequent articles I speed-read, and videos that I watched, all came from the start point that the person asking this question a) was a beekeeper and b) had a working hive and all the necessary equipment to go with it. I had been a beekeeper since about 3.30pm, and all I had was an unassembled hive in the back of my car that was in the latter stages of decay. There was an entire new glossary of words and terms that I had never come across, each of which needed to be deciphered before I could make progress with the basic instruction I was being given. On YouTube, all the videos were either of suspiciously calm bees doing exactly what their people wanted, or of drawling Alabaman hill farmers in checked shirts who called their bees ‘critters’, which made them impossible to take seriously.

Gradually, I learned that there were two basic ways to rehome bees in a new hive: lay a white sheet up a plank that leads from your box to the entry hole of the hive, and wait for them to find, and then occupy, their new home; or just open the lid of the hive and dump them in. The article that 14put me on to this explained that the first of these methods is the most natural and stress-free for the bees, and so I chose it. If I was going to make it as a contributor to, and beneficiary from, this strange new world, then it had to be done in a way that respected my guests; there would be no rude dumping of bees into a hive on my honey farm.

Telling the box that I would ‘be back soon’ as I passed it at the front door, I headed off to set up the hive in the most suitable place I could find in my garden, a small corner between the compost heap and the oil tank that was sheltered from rain, wind and sun. I cleared some long grass, then started what I assumed would be the straightforward task of assembling the hive itself. Suddenly I was in a new and entirely esoteric world of brood boxes, stands, crown boards and queen excluders, with little idea of what they did, and even less of where they went. Being someone with all the fine motor skills of a blue whale, I desperately needed someone’s help at the same time as not wanting to admit to that someone that I hadn’t got a clue what I was doing. However, by degrees I worked out which bit went on which other, and eventually had something on my hands that looked close to, if not exactly like, the hives I had seen. It may have had all the allure of a condemned tenement block, but it had a roof, and it had stuff in it, which for the time being was good enough for me.

Triumphantly, I went back to the house and took a clean white sheet out of the airing cupboard while Caroline wasn’t 15looking. I wanted my bees to feel like honoured guests in their new home, and there is nothing, as I saw it, quite like the feel of Egyptian cotton to create a first impression of luxury and well-being. I wasn’t sure that she would see things in the same way, and opted for the tried and tested maxim that it is normally easier in life to apologise retrospectively than to ask permission.

I put on the veil again, picked up the box and headed back with my guests to their new home. The way I saw it, short of candle-lit tables and a Michelin-starred chef preparing a meal for them, I couldn’t have done much more to make them feel welcome. The only fly in the ointment was the rain, which now looked like it had set in for the evening. If I was expecting a burst of activity and noise as I carefully untied the knot in the sheet and started to open the box, I was to be sorely disappointed. They were all down at the bottom of the box looking out of sorts and lethargic, a mindset that would surely change as they became aware of their new, luxurious surroundings. Slowly, I turned the box upside down and shook its contents down onto the crisp white sheet below.

‘It’s up to you now, guys,’ I told them cheerfully. ‘Get in there quickly before the rain really sets in.’

Once back in the house, I continued my research with diligence and, gradually, the whole hidden, secret, magical, 16beautiful world of the honeybee started to reveal itself to me.

Little by little, I learned with the thrill of a primary school child what this world consisted of. Of a population whose members can think only for the group, never for themselves. Of a single bee who is selected by chance to be fed more royal jelly than the others and therefore become the queen, the sole fertile member of the colony. Of how the queen leaves the hive once, and once only, in her life, for a mating flight during which she is impregnated enough to carry the genetic ability to produce over two million eggs in her lifetime, more than 2,000 in a single day. Of a feminist sorority where the men are kicked out as non-contributors, and even killed, before the winter sets in. Of a world where most communication and decision-making is done in the dark by smell and by pheromones. Of strange dances and heroic deaths. Of a creature who has worked alongside man for over 5,000 years, providing him with honey and being fed sugar in return over the long winter. Of a worker who labours so hard in the long summer days that she lives only a handful of weeks, in contrast to the three or four years of the queen, and who often dies in flight as her own wings shred with the efforts of her day-long foraging. And how all that the world has to show for her tiny life is a twelfth of a teaspoon of honey, and how that pot of honey would cost about £200,000 if all the bees that made it were paid the minimum wage. And above all, I learned that the honeybee population was in sharp decline, 17laid low by the effects of intensive farming, urbanisation, global warming and pesticides, and what this could eventually do to the human family on earth if allowed to run unchecked. Every line I read taught me something that, even as a boy brought up in the countryside, I had never known. Each sentence drew out of me the childlike fascination of a new and utterly compelling thing in my life. And I knew with certainty that I had to be part of it.

There are maybe 80 million domesticated hives in the world, and tonight I would be adding to their number by one.

Or not.

As darkness fell, I went out to check on the progress of my new guests, daring to believe as I did so that they had made the trip up the Egyptian cotton sheet into their new hive and were even now relaxing after an à la carte dinner and setting out a foraging strategy for the next day.

But it was not to be. In the rain and the damp, they had just stayed where they were, with only the boldest scouts troubling to check out what I had prepared for them. A dead bee is diminished in size, and at least half of my swarm had turned in on themselves and wouldn’t be going anywhere, now or in the future. Bees can only ingest enough food to see them through a day or two, and the swarm that I had come across was apparently one that had already been out 18of the hive for enough time to take them close to the limit. Panicking, I removed the lid and crown board of the hive, and tipped the rest of the contents of the box, and the white sheet, into it. Maybe that would fix it.