1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

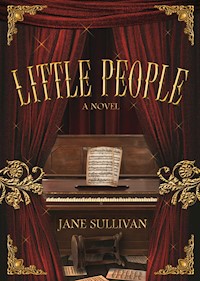

Shortlisted for the 2012 Encore Award A gripping and colourful historical novel based on the 1870 tour of Australia by the celebrated midget General Tom Thumb and his troupe. When Mary Ann, an impoverished governess, rescues a child from the Yarra River, she sets in motion a train of events that she could never have foreseen. It is not a child she has saved but General Tom Thumb, star of a celebrated troupe of midgets on their 1870 tour of Australia. From the enchanting Queen of Beauty Lavinia Stratton to the brilliant pianist Franz Richardson, it seems that Mary Ann has fallen in among friends. She soon discovers, however, that relationships within the troupe and its entourage are far from harmonious. Jealousy is rife, and there are secrets aplenty: even Mary Ann has one of her own. Relief, however, gradually turns to fear as she realises that she may be a pawn in a more dangerous game than she imagined.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

LITTLE PEOPLE

A NOVEL

JANE SULLIVAN

First published in Australia in 2011 by Scribe Publications

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright © Jane Sullivan 2011

The moral right of Jane Sullivan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin c/o Atlantic Books Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

Phone:

020 7269 1610

Fax:

020 7430 0916

Email:

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 74237 885 5

E-book ISBN 978 1 74269 788 8

Printed in Great Britain by

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR DAVID

A woman of considerable physical courage mounted a horse, rode side byside with her soldier-husband, and witnessed the drilling of the troopsfor battle. The exciting music and scene together inspired her with a deepthirst to behold a war and a conquest. This event transpired a few monthsbefore the birth of her child — his name, Napoleon.

During the period immediately preceding the birth of Dante, his youngmother saw a startling vision. She beheld a populated globe rise graduallyout of the sea and float mid-heavens. Upon a high and grand mountainstood a man with brilliant countenance, whom she knew to be her son.

A woman gave birth to a child covered with hair, and having the claws ofa bear. This was attributed to her beholding the images and pictures ofbears hung up in the palace of the Ursini family, to which she belonged.

— Dr Foote’s Home Cyclopedia of Popular Medical, Social and Sexual Science, 1858

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

THE LILLIPUTIANS

General Tom Thumb (Charles Stratton), the one and only Man in Miniature

Lavinia Stratton, his wife: the Queen of Beauty

Minnie Warren, Lavinia’s sister: a pretty, plucky lady

Commodore George Washington Nutt, a sharp fellow with a deal of drollery

THE MERELY SMALL

Rodnia Nutt, the Commodore’s brother: coachman and horse wrangler

THE FULL-SIZED

Mary Ann, an unfortunate young woman

Sylvester Bleeker, manager of the Lilliputian troupe: destined to save the day

Hannah Bleeker, his wife: sharp with her needle

Franz Richardson, a pianist and aspiring virtuoso

Ned Davis, an agent: a provocative fellow

THE OUTSIDERS

Matilda, a tattletale child

Her terrible papa

Dr Frederick Musgrave, a collector of marvels

Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, a Prince of the Realm

SAGACIOUS BEASTS

Erasmus, an Australian bird

Mazeppa, a Wild Horse of Tartary

Innkeepers, lackeys, cabbies, ladies bountiful, poor ruffians,

sporting gents, the great Australian public

Contents

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

AFTERWORD

FURTHER READING

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHAPTER 1

One day, she will ask me the inevitable question. There is much to tell, and I am not certain how to tell it. At least I know where to begin.

I will remind her that I was young, and had always been told that wanting was nothing but covetousness, a sin before God. I had no idea how dangerous the world could be.

It began with a game a gentleman taught me.

‘Matilda tells me you have been wicked, Mary Ann.’

‘No, sir.’

The first time, I tried to explain. Matilda’s papa seemed calm, faintly amused. ‘I think you deserve a forfeit,’ he said when I paused in my awkward story. Gravely he closed the study door, took my hand in his, raised it to his lips. What kind of forfeit was that?

‘That will be all, Mary Ann.’

Later he took to summoning me to his study when no one was about. He would close the curtains, light the lamp, sit on the edge of his desk and talk about a calf that had died at birth, or the time one of his dogs had a thorn in its paw, or the green fields of Norfolk. Now that he lived in the locality of Emu Flat, Victoria, he missed that green: it was very restful. I had not seen him so pensive. He was handsome in a bullish way.

I spent most of my time with Matilda, my pupil, and her family of sulky dolls. You don’t belong here, they said. You have frog hands. Weshall tell Papa.

The maids and the cook kept to different parts of the house. I had occasional words with Matilda’s mama, who liked to wander around the vegetable garden with a sweet smile and a covered basket. I never saw inside the basket. Matilda’s papa was a distant rider on his dusty estate, pausing at a gate or whistling to his retrievers, except when he called me to his study. Before he dismissed me, he would take a forfeit. ‘That is for vexing Matilda,’ he would say. And then he began to add: ‘And for bewitching me.’

In time, his hand-kissing extended itself. He was always gentle, respectful, but his words hissed like steam in a kettle. I was driving him out of his mind. Did I not know the torments a man could suffer? I should take pity on him.

What I felt for him was many things, but pity was not among them. He was uncommonly tall, robust, the king of his domain. When he sat on the edge of his desk with his hands over his eyes, I came to him and took his hands away from his face. That made him smile, and I understood then what form my pity should take. I collected his smiles, took them to my attic bedroom and stored them in a red lacquered box he had used for his cigars. It was my most precious possession.

One day, I passed the drawing room and heard Matilda’s papa and mama talking in low tones. Her voice was cold, his almost unrecognisable. ‘Please, Emily. Please.’

An hour later I was summoned to his study and I waited for him to take me in his arms and guide me to the chaise longue under the window with the closed curtains. But he paced the carpet, would not meet my eye, talked about how dissatisfied he was with my teaching. ‘You may have a month’s wages and I will give you a good reference.’

I forgot myself. ‘I have done nothing wrong,’ I cried.

‘Take your money, go. If you say a word to anyone I will tell them what a madwoman you are. You will be placed in an asylum for the insane and never released.’

I left Emu Flat and came back to Melbourne alone. My menses, always punctual, had not come. I prayed, but the words stuck. I paid for a tiny miserable room in the attic of a hotel by the river and took the rest of my money down an alleyway to a small dark house I’d heard about in whispers. Inside, hanging from a hook in the ceiling, was a cage with a silent canary in it. An old woman was shaving soap into a bucket of steaming water. She looked me up and down, took my money in her glistening hand.

She gave me a blanket and told me to take off my clothes and lie down in my chemise. I kept on my boots and stockings. My bed was a low bench draped with a much-darned sheet; the scratchy blanket smelled of lye. The woman lifted it up over my knees and prodded at my still-flat belly, my thighs, around and inside my private place, and I held my breath until black spots swarmed in front of my eyes. She straightened up. ‘Only just fallen, have yer? That’s good. Most of ’em come in late.’ Then she left the room. Surely there must be more.

Shadows passed on the ceiling. I tried to relax each tense limb in turn, tried not to imagine what might be done with a bucket of soapy water. A door opened into the adjoining room, voices murmured, old and young, both female. Another young woman must be lying there, under a scratchy blanket. Business was brisk. An odd fancy came to me: we were in the pages of a picture book, and the young woman next door was myself, on another page, recovering a few hours later. The canary in the cage shuffled back and forth on its perch. It had pecked out all its breast feathers. Every pore in its skin gaped at me.

All at once a scream from the next room seemed to rip open the wall. I did not even sit up. I rolled off the bench, pulled my dress over my head, threw my shawl over it, ran out the door into stinging rain. More screams and sobs followed me; I ran as they sliced me open. I did not stop running until, back in my little garret, I flung myself face down on the bed, damp dress gaping where I had not buttoned it. No tears; all I had was wheeze.

Why had I run? Stupid terror, but a spirit whispered to me something else: You refused to lie down and be tractable. A second spirit whispered: You’re just finding an excuse for your cowardice. This second spirit was practical: You’ve paid, you can go back. But I knew I would not return.

When darkness came, I changed into my nightgown and brushed my hair like a good girl, but in the mirror was a witch face. I could not sleep because the spirits argued, and the whispers crescendoed to a roaring. So I rose from my bed, holding the red cigar box, crept onto the moonlit lawn. This was what madwomen did. They let down their hair and stumbled about in their nightgowns.

The roaring was in the Yarra Yarra. At the end of the lawn was the river, a black racing tide splintered with fragments of moon. I had not thought a river could run so strong. Come, it roared at me. Was that what I was looking for? Where was the best place? Here, at the edge of the water, a few steps in? Or from the bridge, where my weight would carry me deep? Either way would be quick. I opened my lacquered box, inhaled the scent of tobacco, turned it upside down, shook out all the smiles and hurled it into the water. The wind whipped my hair. Come, roared the river. Then a new thought anchored me, a firm little voice.

You are not mad enough for this. Go back to bed. You will have to carryyour burden as best you may.

I turned upriver towards the bridge. On the parapet, at its highest point, I saw a white shape like a bundle of clothing. As I watched, the shape expanded into a star with five stumpy points. The little star clutched and held itself round the middle, jerked and flailed as it faced down to the water. A child. Sick, or frightened, or trying to pass water? But why did it tremble so? Then the child toppled and fell towards the water in precisely the arc I had contemplated for myself.

There was too much noise to hear the splash. The shape disappeared, then bobbed up again. The river was sweeping it in my direction. It would pass very close to the bank. I ran to the water’s edge and slid down, gasping as an icy grip closed around my ankles, my knees. I floundered, nearly fell, but righted myself, waist-high in the flow. The child was within arm’s reach, swirling in an eddy; still nothing but a bundle, ballooning with air. I pulled it into my arms, but I might as well have grabbed a sack of cannon balls. The fabric, now dark with mud, stretched over the child’s dangling head like a caul, hiding its face.

All at once it convulsed. Limbs snaked around my neck, my waist, gripped with astonishing strength. It would drown us both. I staggered backwards into a fountain of bubbles, the child starfished across my chest and belly, and then a black hum as the Yarra Yarra closed over me.

I rolled onto my knees, scraped my shin on a submerged rock. Kneeling on the rock’s sloping surface, chin above the flood, I held on with both hands and pulled one foot, then two, from the mud. I scrambled up the bank, leaden child dangling beneath my breasts, its legs crossed over my back. I swayed on all fours, reached to prise its arms from my neck. It fell beneath me, slopped like a bag of dough. Did it breathe? Where was its face? Was it even human? Or something that deserved to drown? I straddled it, tried to find its chest through layers of waterlogged fabric, to push water from its lungs, to hear it squeal or snarl. The creature clung, clawed, had me by the ears, pulled my head down. We wrestled in silence. My hand reached its skin.

Lanterns, shouts, splashing, harsh barks. I sprawled on my belly. The claws had gone. I was nothing but stink and blood and icy mud, throat raw, shin athrob, every inch of me shivering. Yellow lights bobbed over my head as I vomited up the Yarra Yarra through my hair, emptying all my cavities, becoming as clear as jelly. A dog ran up and down the riverbank, barking.

CHAPTER 2

When I woke from my stupor, with daylight in my eyes, a strange woman was sitting by my bed, holding my wrist and measuring my pulse.

‘How do you feel?’ she asked.

‘Have I been unwell?’

‘You have coughed up half the river. I took the liberty of washing off a deal of mud. I also gave you a sleeping draught.’ I groaned, tried to sit up. ‘Lie still.’ Under a twist of greying sandy hair were freckles, shrewd grey eyes and a sucked-in mouth. The voice had the nasal twang of an accent I did not recognise, and the elbow on the arm that pulled up the bedclothes had a sharp point.

‘The river … what happened?’

‘You don’t remember?’

‘Not much.’ A faint roaring. A dog barking.

‘You’re a heroine, dear.’ Her twang emphasised the r’s. That voice: it was the one you use to children so they will not be puffed up with praise.

‘I don’t understand, Mrs …’

‘Mrs Bleeker. Sit up. Drink.’ She handed me a glass of warm milk. ‘My husband is Sylvester Bleeker, the General’s tour manager.’ She spoke as if I should know who the General was.

I sipped the milk. My locket lay on the table by the bed; but the table was marble, not plywood, and the sleeves around my wrists were not my sleeves.

The strange spiky woman watched me frown. ‘I moved you into a more comfortable room. Rest assured, there will be no expense.’

‘You are very kind, but I really am fine.’

She gave me a long look. I thought that the wrinkles at the corners of her eyes might mean kindness or calculation. I pulled the nightgown up around my neck. When she reached out with both hands, I began to shrink back, thinking she would touch, dispassionate as a doctor, my swollen breasts and tender nipples. Instead, she took both my hands in hers, drew them into the light, pressed them as a phrenologist measures a head.

‘We must notify your family, Miss …’

One word swam into my head, and then another. ‘Mrs … Carroll.’

‘We must notify Mr Carroll, then.’ She let my hands go.

I waited, and more words swam in. ‘Mr Carroll passed away.’

‘I am sorry.’

I ran my gaze along the mantelpiece, the clock, the Toby jug. ‘He was of the clergy, he had red cheeks …’

Mrs Bleeker raised an eyebrow.

‘But very sober in his habits,’ I went on hastily.

‘You were both English? Your voice is refined.’

‘We came from England to better ourselves. But then he was taken with the pleurisy. It was very sudden. Now I have no one, no family. I cannot pay you, I have spent the last of my money.’

Now she would leave. But all she did was pat my right hand. Then she held the fingers apart, examined the webbing that stretched between them to the lower knuckle. She picked up my left hand, spread the fingers again; I fought the urge to snatch back my hand.

‘I was born so,’ I said. ‘I cannot wear gloves, or rings.’

‘You will want a position. Have you been in employment?’

‘I was a governess: I taught reading, writing, drawing, pianoforte. It is true, I am in need of a position. I was told there were many opportunities for governesses in Australia. I have a good reference. Do you know of anyone who —’

‘Can you sew a fine seam?’

‘Pretty fine.’ A strange question to ask a governess. She squeezed my left hand, took the empty milk glass and left the room.

When I woke again I was alone, but on the chair beside the bed was a large bundle of black fabric, and on the coverlet just below my chin was a white glove and a bobbin of white cotton pierced with a needle. I sat up, turned the glove over and over: silk, smelling faintly of lilacs, about the size to fit a five-year-old with slender hands, three of the finger ends and thumb frayed and gaping. I sewed up the finger and thumb ends with small, tight stitches and embroidered two rows of fancy stitch along the hem before a memory rose, with a wave of nausea, of white fabric ballooning on dark water.

Mrs Bleeker returned with chicken broth, bread and more milk. She waited behind the door until I had used the chamber pot under the bed, then put down the tray and fetched a jug, soap and a bowl of water. While I washed, she picked up the glove, turned it inside out, stretched it, thrust her little finger inside. ‘Not half bad,’ she murmured, then looked at the hem and sniffed. ‘What counts is strength. All the clothes must endure hard use. Yanked on and off, tugged at by ragamuffins —’

‘Mrs Bleeker, do you have a position for me?’ I paused, tried to slow down my eagerness. ‘Does your child require a governess?’

‘Child? What child?’ Her voice was sharp. ‘There is no child. Eat your broth.’

I sat meekly at the marble table.

She lifted the mass of fabric from the chair by the bed. ‘I wore this when I played the mother of one of Bluebeard’s wives,’ she said in a softer tone. ‘Excuse me for saying this, but my cries over my dead daughter were heart-rending, everyone said so.’ The black gown had stripes of alternating matte and shiny silk. ‘This would fit you well.’

The broth smelled delicious. I was suddenly starving.

I spent another day and night in the room, eating meals at the marble table, sitting by the window in the soft woollen nightgown, mending seven pairs of little gloves of silk and kid, repairing a rip in a tiny muff of black fur that sat like a kitten in my lap. The window faced away from the road and river; a calm rain fell on rows of carrot tops. From time to time, Mrs Bleeker swept in and out with trays and garments. Once she stayed a little longer, picking up the locket and dangling it from her fingers. I felt a brisk rummaging through my heart.

‘Do you have a job for me? I sew, I sketch, I do anything. Surely there is a job for me?’

Mrs Bleeker took the tray and left. I held myself back from running along the corridor after her like a puppy.

I woke early, covered in sweat. I wrapped myself in the coverlet and waited in the chair for dawn. My breasts tingled, I felt slightly sick. Rain pattered on the window. This was what it was like, to be in limbo. I forbade myself to think of my burden, the past, or the future, and I would not try on the black dress. But I did pick it up when daylight came, and in the pocket I found a piece of folded paper. I opened it and the print shouted at me.

Sylvester Bleeker, manager

Positively Twenty-Nine Days Only

at the Polytechnic Hall, Melbourne

Four of the Smallest Human Beings of mature age in the World

Perfect Ladies and Gentlemen in Miniature

The original and only GENERAL TOM THUMB and his WIFE

(Mr and Mrs Chas. Stratton), COMMODORE NUTT and MISS

MINNIE WARREN in their BEAUTIFUL PERFORMANCES

consisting of SONGS, DUETS, COMIC ACTS, BURLESQUES

and LAUGHABLE ECCENTRICITIES.

Ned Davis, agent March 1870

I put down the paper, grabbed the nightgown I was wearing in my fists and pulled the folds up over my head. I felt with my hands how the cloth flattened and distorted my nose and mouth, turned my eyes into ghostly hollows. Was this how a simple garment, soaked in water and mud, turned into a caul? Was this how a man became a monster?

Footsteps at the doorway. I whirled, pulled the gown from my head. Mrs Bleeker stood with her arms full of white linen. She put down her bundle, and frowned and sniffed over the latest glove I had repaired.

‘You have ladies,’ I said. ‘Mrs Charles Stratton and Miss Minnie Warren. I would be a very good ladies’ maid.’

‘It is not a position for a governess, or a clergyman’s widow.’

‘But I can mend their clothes, dress them, run errands. I can help you too. I can be your assistant. Please, Mrs Bleeker.’

She hesitated. ‘I will have to ask my husband.’

When she came back, she had an offer.

‘Twenty-two pounds. That’s for nine months, the length of our tour of Australia. Board and all expenses paid, including travel. You will be assistant wardrobe mistress and ladies’ maid to Mrs Stratton and Miss Warren when required.’

I thought of the meagre governess’s wage, held my breath.

‘There will be much hard work and constant travel,’ Mrs Bleeker went on. ‘We will not always stay in such pleasant hotels. The people who come to see us can be rude and vulgar. But then, Mrs Carroll — what is your Christian name?’ I told her. ‘Mary Ann, you know more of Australians than we Americans.’

The twang. Of course. Our friends from the New World.

‘I am most grateful, Mrs Bleeker.’

‘This is all conditional, mind. If the post is agreeable to you, I shall arrange for the sisters, Mrs Stratton and Miss Warren, to interview you. It will be up to them. And the General. And my husband.’ She tweaked the curtain at the window. ‘The rain has stopped.’ She picked up the dress from the bed and held it against me. ‘Black becomes you. I have brought clean underclothes. Will you not try it on?’

She retreated behind the door and waited while I took off the nightgown and put on the camisole, pantaloons, corset, petticoat and hoop. Then she helped me into the dress, showed me the looking glass: pale face and feet, dark tangled hair, black and silver stripes rippling like the moon on water.

‘This gown is too fine for me,’ I said.

‘Nonsense. It’s stage finery.’

In the mirror, over my striped shoulder, Mrs Bleeker stared at me. I saw myself with the same gaze: startled-deer eyes, face still childishly round, but for the jut of my chin. Her gaze travelled down, up, hovered just below my waist.

‘I had almost forgot.’ She took my left hand and slipped a gold ring onto my third finger. It stopped at the joint, just above the web of skin, but it stayed in place. ‘There. You can wear a ring after all. Only painted gold, I fear. We have many such props. Perhaps it will serve as a reminder of poor Mr Carroll.’

I could not help myself. I took Mrs Bleeker’s thimble-callused hand in mine, pulled it to my heart and began to cry.

‘Oh, there, there,’ she said, looking around furtively as if someone would appear and blame her for the tears.

Of course I was curious about the little people. I had never seen any kind of little person, but I had touched one, as we struggled by the Yarra Yarra, and nausea rose when my fingers recalled the fishy wet skin.

I thought of Mr Quilp the dwarf in Mr Dickens’s book, with his hook nose and villain’s smile. I fell asleep while sewing a glove and I entered a hall where the Perfect Ladies and Gentlemen in Miniature stood on a high platform, their eyes level with mine, to judge me. They were not perfect. They were hunchbacked, and their limbs were stumps ending in claws. Their ruddy Toby-jug faces were wizened and crushed and they wore smocks fit for madmen and women. They pointed at me and screeched like bats, You must be tractable, and threw out strings baited with hooks that caught in my clothes and drew me towards them. They would tie me down like Gulliver. I woke, the glove crushed in my hand.

Then Mrs Bleeker came to tell me it was time to meet the ladies, and I wanted to hide behind the curtains, but I scolded myself for such childish fears.

In the sisters’ boudoir, bright dresses, shawls and underwear lay strewn over the beds and furniture amid an overpowering scent of lilacs. At the heart of scent and colour, the furled bud, was Mrs Lavinia Stratton, her eyes fixed on mine.

Imagine a society beauty, and all the things people say about her. Tiny waist, lustrous black hair, exquisitely modelled neck and shoulders, velvet skin, finely shaped eyebrows and black eyelashes. Imagine hair loose, slim form wrapped in a Japanese robe of rose and white silk, dainty feet in matching rose slippers. Now imagine she is just a fraction less perfect: cheeks a little too round and babylike. Now imagine she sips from the magic bottle labelled EatMe, and she shrinks down, still in perfect proportion, until she is no taller than my hip. And this shrinking concentrates her beauty, as cordial sweetens the strawberry.

Beside her was Miss Minnie Warren, a bonny fairy in a green silk wrap and green slippers, a little smaller, a little chubbier, hopping from one foot to the other. If she were not so close to her incomparable sister, and her own cheeks were not unfashionably ruddy, many would declare her a beauty in her own right. Lavinia, hands folded, could pass for a figurine; but Minnie was a blur of movement. Everything from her hair to her fingers was flyaway.

My eyes filled with tears; whether from wonder or the scent of lilacs, I could not tell. I could scarcely believe that one such creature existed on this earth, let alone two.

‘Kneel,’ Lavinia said to me, her voice imperious, musical. Did she demand a queen’s homage? But she was pointing to a pincushion on the floor in front of her, and I saw the hem of her robe was half pinned, the edge ragged. Behind me, Mrs Bleeker cleared her throat. I kneeled and continued pinning.

‘Look at me,’ Lavinia said. She was fanning her hair out over her shoulders. Her eyes were a startling violet. ‘What do you see?’

‘A beautiful lady,’ said I.

‘Not a beautiful little lady?’

I hesitated. Was the question a trap?

Lavinia smiled. ‘Always remember when you look at me that you are in the presence of a wonder of the world.’

‘Two wonders of the world,’ said Minnie, her voice high and a little sharp. Both spoke with Mrs Bleeker’s twangy accent.

‘I am the Queen of Beauty,’ Lavinia continued. ‘I sing like an angel. I am all that the most fastidious fancy could desire in a woman. Everyone says so.’ She shrugged the robe down a little, giving me a glimpse of powdered skin, then pulled it tight. ‘And I am highly intelligent, but nobody says that. At all times, my talents must be presented to best advantage.’

‘And my talents too,’ said Minnie. ‘Don’t forget my talents.’

‘As if we could,’ said Lavinia drily, shooting her a look. Then she turned back to me. ‘We are very much indebted to you, Mary Ann.’

I nodded, bent to her hem. Mrs Bleeker stood silently behind me, but her eyes were needles in my back.

‘You are a clergyman’s daughter,’ Lavinia went on. ‘And a clergyman’s widow. You look very young. What are you, seventeen?’

‘Twenty. I am newly widowed.’ I felt about to sneeze. I wanted to tell Lavinia a story of my blameless life, but the lilacs swelled my tongue.

‘Such is fortune for us poor women.’ Lavinia put one hand to her chin, tapped her rosebud lips with her forefinger. Her rings flashed. ‘You have worked with children. You sewed up my gloves. You braved the Yarra Yarra. You must have a cool head in a crisis. It is all crisis with us, is it not, Minnie?’

Minnie chuckled.

‘And yet,’ Lavinia continued, ‘I am not convinced we need a ladies’ maid on this tour. We have managed very well so far without one.’

A sneeze rose into my head, but I fought it back. ‘I believe I am not the panicky type,’ I said firmly. ‘I am very diligent and hard- working, and I use my head. I’m sure I can rise to any challenge you might set me.’

‘You are not backward in coming forward,’ said Lavinia. Was that a rebuke? ‘Very well, you shall have your challenge. Mrs B, what is the time?’

‘Twenty past three.’

‘So. Here is your task. You must dress me in my Worth lavender grosgrain gown and put up my hair, and then you must dress my sister in her primrose gown and put up her hair too. Just a simple knot. Mrs B, you can give her hairpins but you must not help her.’

That was easy enough.

‘And it must all be done by half past.’

Ten minutes? I might as well leave now, I thought, and beg in Melbourne’s alleyways. But it must be possible: no harder than dressing Matilda’s dolls. I turned to the bed and flipped through the rainbow of silks, satins and velvets until I glimpsed lavender, pulled out the gown and rushed to Lavinia. She stood with her arms held out, let me pull off her Japanese robe. I felt the faint trembling of her effort to keep herself calm, still, as if she stood balanced on a tiny point. Beneath, she was in her crinolette and underthings. She stepped into the dress and I coaxed her arms into the openings, smoothed and pulled the dress tight. Confusing braids and fringes, tiny hooks and exquisitely covered buttons set my fingers afumble, but somehow I got her fastened in, wound her hair into a hasty knot and pinned it in place. She patted it as if reassuring an unruly pet.

Mrs Bleeker consulted the clock on the mantelpiece. ‘Twenty-three past.’

Good, that left more than half my time to attend to Minnie. But when I drew out the primrose gown, she laughed, flung off her wrapper and twisted away from me like a child playing chasey. I could not get her to step into it: I had to throw the silk over her head and then grab each flailing arm in turn and push it into the sleeves, wanting to smack her but not daring to hurt her or rip the delicate fabric.

‘Minnie dear,’ Lavinia cried in reproach, but she was laughing too. It was a much simpler dress than Lavinia’s, but Minnie kept wriggling out of my grasp, and when I tried to do up the buttons, she did can-can kicks under her frothing skirts. I despaired over her curls, pinned up the long locks and left the rest to dance Princess Eugenie–style around her cherubic face. We stood panting, eyeing each other.

‘Thirty-one past,’ said Mrs Bleeker.

‘That’s not fair,’ I cried. ‘You saw —’ Mrs Bleeker frowned and clicked her tongue at me.

‘I saw,’ said Lavinia. ‘But if we were backstage, we would miss our cue.’

I glared at Minnie, who widened her angelic eyes.

‘However,’ Lavinia went on, ‘in view of my sister’s skittishness —’ ‘I am not skittish! It’s my natural spirits!’

‘— in view of my sister’s spirits, I will allow that you were very quick, Mary Ann … Minnie dear, you absolutely must let that hem down. I have told you time and time again. When you walk along the runway, all the gentlemen will see your ankles and Lord knows what.’

‘Oh, bosh. It’s exactly the length that Paris is wearing this season,’ said Minnie.

‘Nonsense. Think how fast you will look.’

‘Better fast than frumpy, Vin dear.’ Hands on hips like a tiny washerwoman, Minnie looked as if she were about to stick out her tongue at her sister.

Lavinia’s tone grew stern. ‘Altogether too much spirit. Have you had your medicine today?’

‘She will take it with her tea,’ said Mrs Bleeker. The parlourmaid had arrived with a trolley, and the sisters fell on it, jostling each other as they reached on tiptoe to the top tier of the cake tray. A scent of honey competed with the lilacs. Was I hired or not? I looked towards Mrs Bleeker, who gave a slight shrug.

‘Are you ladies decent?’ The cry came from the doorway, in a high tenor twang.

‘Come in, Charlie,’ said Lavinia.

Mr Charles Stratton, known as General Tom Thumb, strode into the boudoir, spurs clinking. A fine-looking fellow with strong eyebrows and full cheeks, his portliness suited him. He was dressed as Napoleon and moved with a stiff-legged strut as if surveying his empire. He had an erect carriage, a sparse gingery beard, a brave cockade in his hat and high boots buffed without mercy. He gave Lavinia a smacking kiss on the cheek, smiled at Minnie and Mrs Bleeker, took a slice of cake from its stand, broke off a piece and tossed it into his mouth. A hair’s breadth taller than Lavinia, he seemed to fill the room.

‘First-rate plum cake. You ladies have the best teas.’

His voice, high for a man, was deep compared to the ladies’ chirrups. Littleness concentrated his wife’s beauty; for him, littleness concentrated his masculinity, and this seemed to me even more marvellous. All three little people had the plump, fresh look of sparrows who might beg for crumbs, then hop under your nose and devour your whole dinner.

‘Is everything all right, Charlie?’ said Lavinia, gazing at him fondly.

‘Right as rain. How lovely you look, my dear. And you too, Minnie. And …’ He smiled at me. ‘Who might you be, missy? Come for my autograph?’

‘This is Mary Ann, General,’ said Mrs Bleeker. ‘She is a clergyman’s widow, we are considering hiring her to help out.’

Charlie — for so I would come to think of him, though I always called him General — looked me up and down, and I straightened like a soldier on parade. He stuck his thumbs into the armholes of his white waistcoat and thrust out his chest and stomach until the buttons were in danger of popping open. He drew his head back to catch my eye, his top chin sharp, his lower chin more rounded, and it seemed as if he were looking down at me. As he stared, I began to feel that my fancy of cheeky sparrows was all wrong. Charlie and the ladies were the right size, and Mrs Bleeker and I were clumsy giantesses.

I hid my huge hands behind my back as he began to frown.

‘Has Mr B approved this? Do we need any more help?’

‘She is the one, Charlie.’ Lavinia nudged his arm.

‘What’s that, Vin?’

‘The one who rescued you, when you lost your footing on the bridge and fell into the Yarra Yarra.’

Charlie’s gaze dropped. He gently brushed Lavinia’s hand from his arm, and a flush crept across his cheeks. My head roared again with a cascade, a slithery monster, and I averted my eyes as we stood like bashful children.

He will never let the troupe hire me, I thought, if I make him remember.

I felt his eyes on me once more and returned his gaze. His face was still flushed, but now it glowed with hope and an anxious little smile.

‘How is your health, Mary Ann?’

‘Very well, thank you.’ My reply was automatic, but I was sure my puzzlement showed.

‘Are you sure? Just lately? Ever feel a little peaky?’

Surely he could not know of my burden. I opened my mouth to insist I was well. He watched me, still smiling, gave me a little nod, his right eye twitched in something that was nearly a wink, and I realised what I should say.

‘I have felt a little indisposed lately. But it is nothing. I am more than capable of any amount of work.’

‘Well said,’ he cried, sweeping off his hat. ‘General Tom Thumb at your service, young woman. The General is totally in your debt. You saved him from oblivion in a spiteful river at the ends of the earth, and we will reward you handsomely.’ He took my hand in a firm paw, a little sticky with plum cake, and pumped it up and down.

‘How do you do, sir. I am glad to see you so well,’ I said.

He gave off a comfortable man scent of brandy and cigars.

‘What a warm hand,’ he said. ‘I have a feeling you will bring us good fortune. Let us drink a toast. Mrs B, do we have brandy?’

‘We have tea, General.’

‘That will do. Let us charge our glasses — I mean, cups.’

The three little people held out china cups, and Mrs Bleeker poured from the teapot.

Charlie raised his cup high, held my gaze. ‘Let us drink to youth and hope, to a new dawn. Not — as some in this troupe would have us believe — a false dawn.’ For a moment, his voice deepened. Lavinia and Mrs Bleeker exchanged a swift glance. Four of theSmallest Human Beings of mature age in the World, the pamphlet had said. Where was the fourth, and why wasn’t he here?

The cups rose, clinked together, and I felt an almost pleasurable dizziness as I stood in a circle of smiles. ‘To the future,’ said Charlie. I had no idea why he wanted me to act a little peaky, but I would have no trouble doing it.

Mrs Bleeker drew me back from the circle. ‘Well done,’ she whispered. ‘Now all you have to do is impress my husband.’

ACT ONE

The girl looks all of a puzzle. We have that effect sometimes on those who have never seen us before. Or perhaps she is wondering why she had to kneel to me. It was not just so she could pin my dress, or so I could look her in the eye. This is what one does before a queen, and I think I have been a queen for most of my life, long before Mr Barnum manufactured me so. It was necessary for a young person such as myself to have dignity and command. Otherwise I would be nothing but a doll, to be dandled and discarded. Look at the Queen of England: not tiny, to be sure, but certainly a plain little dumpling, as my husband irreverently calls her. Even her crown is little. But Lord, such dignity. Such command.

My reign began on a sled in Middleborough, Massachusetts, during the winter I turned six. Father said I looked like a Chinese emperor. I sat wrapped in woollen shawls, wearing a red stocking hat, while my schoolmates pulled me. When I yelled directions, they swerved whichever way I wanted. We played that game every winter for five years. Sometimes the little brothers and sisters rode on the sled, but they whined and fell off and got left behind in the snow. They did not have the knack of command. Minnie was always too young to go with us (there are eight years between us sisters), and though she cried and begged it was just as well: she would have tossed and rolled and sent us all skidding to perdition.

Dignity came later and was harder won. I thought I would be the queen of Colonel Wood’s floating theatre until I saw Miss Hardy’s button boots. I was sixteen then and quite the heir presumptive. But those boots gaped at me in all their enormity on the threshold of the stateroom we were to share on the steamboat. There was a bulge in the leather of each boot where the big toe poked up. Who could fill those shoes?

Miss Hardy was more nurse than queen to me. She came from Wilton, Maine. She was double-chinned, gentle and affectionate, smelled of gardenias and measured eight feet tall. Once I had overcome my awe, I would climb into her lap for a sleep, or to have my frequent headaches soothed as the steamboat throbbed its way down the Mississippi.

Colonel Wood was my cousin, had a well-trimmed goatee, wore white suits without a speck of soot on them and always carried a pair of white gloves; and because of all these things my parents trusted him when he asked me to travel for a season on his showboat. Every day, wearing one of the three matching ensembles in royal blue that Colonel Wood had made us pay for out of our wages, Miss Hardy and I took a promenade on the floating theatre stage. The customers greeted us with gasps and cheers and cracks about the long and the short of it. I assumed Miss Hardy caused all the commotion, until some visitors approached me, stooped down and peered most impudently at my face and my bosom.

‘Why do they stare so?’ I asked Miss Hardy afterwards.

‘Don’t mind them. They just want to be sure.’

‘Sure? Of what?’

‘That Colonel Wood isn’t humbugging them with a little child.’

‘How do you do,’ I said, curtseying to the next gentleman who came close to inspect me. ‘I am Lavinia Warren and I am sixteen years old.’

‘Of the Plymouth Warrens? Who came to Massachusetts in 1650? Three brothers. One was lame and had a humpback, one had very large ears, one had six fingers on one hand. I am descended from Stephen, who had six fingers.’

I watched him in silence.

The gentleman cleared his throat. ‘Has any member of your family six fingers on one hand or six toes on one foot?’

I drew myself very straight, looked up into his watery eyes. ‘I am descended from William, Earl of Warren, who married the daughter of William the Conqueror. We came to America on the Mayflower. General Joseph Warren laid down his life for his country at the battle of Bunker Hill. I am sorry to disappoint you, sir, but no one in my family ever had six fingers on one hand, or six toes on one foot, or a limp, or a humpback, or very large ears.’

The gentleman looked hard at my hands and feet, then back at my grave face. Could he tell I was chaffing him?

‘Or a deficient brain,’ I added.

‘Well done, dear,’ whispered Miss Hardy. ‘You tell ’em.’

Then the war began, and we had to leave the South, where it was not safe to stay, in case we were caught up the creek behind enemy lines.

‘You are never going away again,’ my mother told me when I returned home. ‘The world is not safe for you.’

‘It seems no less safe for me than for any other soul,’ I replied.

For a while I went back to my old school to teach, but standing on a chair to rap knuckles with a ruler did not seem work I was cut out for. So I resumed my old round of cooking, sewing and housekeeping. I would not give myself airs, pretend I was too good for such tasks. And yet they vexed me, and Minnie vexed me more.

She was nine then, my little raggedy shadow, grown almost up to my shoulder. She followed me everywhere, as she had always done, asking me again and again to tell her stories of Miss Hardy and the gentlemen who inspected us. I am sure I was very patient. I told her that if she wished to meet the public, she must fix her deportment and learn tidier ways. She took to pulling the pins out of my hair and using them to fasten impertinent and badly spelled labels to my back. Steme Bote Quene, Hoyty Toyty Miss and the like. I ask you.

I felt I had to get away. I could choose between another river tour with Colonel Wood, in a safer part of the country, or an offer from a Mr Barnum to appear at his American Museum, on the corner of Broadway and Ann Street, New York, to be followed by a tour of Europe. I was inclined to take the Colonel’s offer, but then Mr Barnum invited my parents and myself to his home in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Let me pass on the opulent appointments of his magnificent house and say only that I found him a tall dark fellow with a florid complexion who gazed at me as if lovestruck.

‘Miss Warren,’ he boomed. ‘You are a miracle. A Queen of Beauty.’

Well. Such soft soap. I told him I was sorry, but I was already engaged. Then my mother said I was not exactly engaged at present, which made me frown, and I assured Mr Barnum that Colonel Wood was making my worldwide reputation.

Mr Barnum found that very funny. ‘On a paddleboat up a creek? Miss Warren, you deserve better than a bunch of Southern riff-raff. You deserve kings and queens and emperors at your feet. I can give you the entire Americas, Britain, Europe, Asia … Australia, if you wish it.’

I told him there was no need to get barbarous. He made to say more, but I hushed him and told him I would not wear royal blue, it did nothing for my complexion. He positively danced around me, told me I would wear any colour, style or fabric I desired, no expense spared, gowns from Madame Demorest of Broadway and jewellery from Messrs Ball and Black. He offered me his hand, which swallowed my own. My mother was clinging to my father’s arm, both smiling. I felt light, ready to float away, except for the red hand anchoring me.

On Sundays, when the American Museum was closed and the crowds had gone home, the Great Skeletal Chamber became a nursery and playground. I was surprised that the resident children of the museum were not frightened by the thunder lizards and their still greater shadows flickering on the wall. But they had seen the miracles so many times.