7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

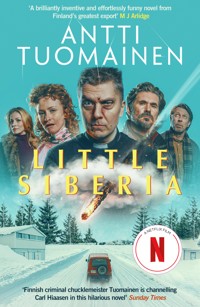

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The arrival of a meteorite in a small Finnish town causes chaos and crime in this poignant, chilling and hilarious thriller, by the international bestselling author of The Rabbit Factor and The Man Who Died – MAJOR MOVIE coming soon to Netflix! `With moral dilemmas, plenty of action, and the author's trademark mixture of humour and melancholy, this is Tuomainen's best yet´ Guardian `Scandinavia's answer to Carl Hiaasen delivers another hectically silly crime caper involving a military chaplain, a suicidal rally driver and a very expensive meteorite´ The Times `Finnish criminal chucklemeister Tuomainen is channelling Carl Hiaasen in this hilarious novel´ Sunday Times ***The Times BOOK OF THE YEAR*** ***Shortlisted for the CrimeFest Last Laugh Award*** ***Shortlisted for the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger*** ***WINNER of the Petrona Award for Best Scandinavian Crime Fiction*** _________________ A man with dark thoughts on his mind is racing along the remote snowy roads of Hurmevaara in Finland, when there is flash in the sky and something crashes into the car. That something turns about to be a highly valuable meteorite. With euro signs lighting up the eyes of the locals, the unexpected treasure is temporarily placed in a neighbourhood museum, under the watchful eye of a priest named Joel. But Joel has a lot more on his mind than simply protecting the riches that have apparently rained down from heaven. His wife has just revealed that she is pregnant. Unfortunately, Joel has strong reason to think the baby isn't his. As Joel tries to fend off repeated and bungled attempts to steal the meteorite, he must also come to terms with his own situation, and discover who the father of the baby really is. Transporting the reader to the culture, landscape and mores of northern Finland Little Siberia is both a crime novel and a hilarious, blacker-than-black comedy about faith and disbelief, love and death, and what to do when bolts from the blue – both literal and figurative – turn your life upside down. _________________ `Tuomainen is the funniest writer in Europe´ The Times `By no means Nordic noir of the familiar variety, this is eccentric, humorous fare, reminiscent of nothing so much as a Coen Brothers movie´ Financial Times `Tuomainen continues to carve out his own niche in the chilly tundras of northern Finland in this poignant, gripping and hilarious tale´ Daily Express `While the plots of many Nordic noir writers are turning ever more grim, Finland's Antti Tuomainen opts these days for a wittier, lighter touch … quite the ride´ Observer `The biting cold of Northern Finland is only matched by the cutting dark wit and compelling plot on this must-read crime novel´ Denzil Meyrick `A brilliantly inventive and gloriously funny novel from Finland's greatest export´ MJ Arlidge `Told in a darkly funny, deadpan style … The result is a rollercoaster read´ Guardian `Right up there with the best´ TLS `Through it all, Tuomainen maintains his singular tone, which mixes black humour with genuine, sometimes biting, sympathy for desperate people, provided that none take their needfulness too far … Little Siberia is a gripping thriller whose complications pile to precarious, intoxicating heights´ Foreword Reviews

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

v

Little Siberia

ANTTI TUOMAINEN

translated by David Hackston

vii

Dedicated with warmth and gratitude to Aino Järvinen, my high-school Finnish teacher.

Thank you for the fails as well as the passes, and particularly the time thirty years ago when you said writing might be my thing.

I promise I’ll try my best.viii

x

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

(Dante, The Divine Comedy, trans. H. W. Longfellow, 1867)

LITTLE SIBERIA

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Warm Koskenkorva vodka scours the inside of his mouth, sets his throat ablaze. But he controls the sideways swerve, and the car comes out of the bend at almost the same speed as it went in.

He takes his right hand from the steering wheel, changes gear, glances at the speedometer. A shade over 130. For winter driving, this speed is excellent, especially in freezing conditions along a winding road across the eastern side of Hurmevaara. You also have to factor in that visibility is limited at this time of night – despite the brightness of the stars.

His left foot touches the clutch and his right presses down on the accelerator. He raises his left hand again and swallows a sliver from the bottle.

This is how you should drink Koskenkorva. First a big gulp to fill the mouth, so strong it lights up like a ball of fire and feels as though it could knock your teeth out. Then a smaller sip, a thin gauze of liquor that barely wets the lips but that’s enough to extinguish the fire and helps you to swallow the first proper mouthful.

And this is how you drive a car.

He arrives at a long, gentle downward slope, which slowly veers to the right, but so slowly and smoothly that the curve is deceptive. At first it looks as though all you need to do is keep the car straight and your foot on the gas, pedal to the metal. But no. The road then slopes slightly to the left, and the faster you drive the more it feels as though the road wants to buck the car from its back. He grips the steering wheel; he knows he’s going about 165 kilometres an hour. It’s the speed of champions. He knows that too, and the knowledge hurts.

On his right he catches a brief glimpse of the ice stretching across 2Lake Hurmevaara. Fishermen’s flags jut out from the surface, marking their fishing holes and nets. He sometimes looks at these flags when he takes this route, because glanced at quickly they almost seem like rows of cheering crowds. But tonight he doesn’t need applause.

He keeps the steering wheel angled a fraction to the right to correct the slope of the road surface. As another bend comes into view up ahead, he begins an engine brake. This requires the utmost coordination of hands and feet, the seamless collaboration of clutch and gearstick. He sets the bottle firmly between his thighs, casts his left hand up to the steering wheel, moves the right down to the gearstick, presses down on the clutch and with the accelerator gives just enough gas. He controls the car by harnessing its own power. The brake pedal is for amateurs – guys like the one who’d lent him this car.

After a short, even stretch of road, the car arrives at the foot of a hill with two ridges. He can feel the burning at the bottom of his stomach.

This isn’t the Koskenkorva. This is fate.

He uses all the power the car can muster. It requires the utmost control of both the Audi and the situation. You can’t just put your foot on the gas. If you do that, the vehicle will be impossible to steer. And at a speed of over 180 km/h, that means careering into the heaps of snow along the road’s verges and after that the car would spin on its roof a couple of times – if you’re lucky. If you’re not and you hesitate even slightly, the car will plough right into the thick spruce forest, where it would twist itself like a gift wrapper round a frosted, metre-thick tree trunk.

He doesn’t believe in luck. He believes in speed, sufficient speed.

Especially now, as everything is approaching its conclusion. A conclusion that suits him fine.

The Audi reaches the top of the hill travelling at around 200 km/h. And when it gets there the car launches into flight. As it takes off, he raises the bottle to his lips. This requires as much precision as driving. His left hand is firm but relaxed. Cold Koskenkorva floods 3his mouth as the car flies through the frozen night. Sweet flames tingle across his lips as one and a half tonnes of steel, aluminium, roaring engine and new studded tyres obey his command.

The Audi flies far and long. It touches down at the very moment the bottle returns to its rightful place between the driver’s thighs.

He slips down to a lower gear, accelerates, changes gear again. A downhill slope, a tiny stretch of flat ground, then another hill. And another flight. He catches a glimpse of the flashing red dials on the dashboard and the glinting bottle. The speedometer shows 200, the bottle contains only a few more gulps. When the studs of his tyres once again strike the surface of the road like machine-gun fire, he smiles – as much as a face gnawed with booze possibly can.

He is in his element. Those who turned their backs on him will live to regret it. He’s been shunned, ostracised, taken for a fool. He might die, but by dying on his own terms he will rise above everything and everybody. He will achieve something, pass them by, waving to the slower cars as he goes. The thought is a potent one, strong and warm. It burns his mind like the liquor in his mouth.

He slurps from the bottle until it is empty.

The last stretch. The Audi howls.

He opens the window. His face freezes, his eyes stream. He throws the bottle out into the snow.

An open stretch of road. At the end of it, a T-junction. He is not turning either way. He is heading right for the rockface in front of him.

Maximum speed always depends on the driver. People never talk about this. They just say, such-and-such a car’s top speed is this or that. Nonsense.

He checks the dial: 240 – in a car that is supposed to stall at 225.

He looks at the road ahead. The last kilometre. Ever.

This is how it’s all going to end, he thinks as the car explodes.

He can feel the explosion around him.

What he sees in that split second: the world is engulfed by a 4huge flash of light, followed by a shadow just as immense; light and shadow both arriving vertically from above. His heart stops and starts again, now throbbing in heavy, hollow beats, like hammer blows against metal. His senses, all five of them, seem to sharpen and come into focus in a way he has never experienced before. He can smell the tear in the car roof, taste the strange, pliable material inside the seat, feel the pressure wave push against his hands. At first he can hear everything, then, as his ears become blocked, he hears the explosion continue inside his head.

He acts instinctively. He shifts to a lower gear, slams his foot on the clutch, the accelerator and the brake. Engine brake, hand brake – a controlled spin. The car slides into the intersection and comes to a stop.

He isn’t quite sure how long the moment of stasis lasts. Maybe a minute, maybe two. He cannot move. When his faculties finally return and he manages to release his grip on the steering wheel and focus his eyes on what is around him, he has no idea what he is looking at.

Of course, he understands the fact that right above the passenger seat there is now a gaping hole in the car’s roof. But there’s a hole in the seat too. The diameter of the hole in the roof is slightly smaller. He congratulates himself on the liquor. Without that in his system, it would be impossible to remain this calm.

He manages to unclip his seatbelt, then stops for a moment. It seems necessary to go through the facts again. The hole in the roof, the hole in the seat, himself. The holes are right next to him.

He steps out of the car and looks up and down a few times. Endless banks of snow, the frozen night lit only by the bright light of the moon and stars. The snow crunches beneath his driving boots as he paces around the car. The hole in the roof is like a pair of lips set in an inside-out pout. He opens the passenger door. Yes, the pouting lips are kissing the inside of the car. The hole in the seat opens inwards; it looks almost lewd. He peers into the hole. It is black. He deduces two things. There can’t be a hole in the bottom of 5the car; if there were, he’d be able to see snow. Whatever made that hole passed first through the roof, then the seat – then stopped.

He backs away from the car. The snow crackles. His heart is racing.

He was preparing himself to die. Then something happened, and he’s still alive.

It’s the Monte Carlo rally today. People all around. Alpine liquor. Holes don’t just appear in cars. Things don’t fall through their roofs from…

The sky.

He looks up like a shot. Of course, he can’t see anything. You can rarely see anything in the sky. With the exception of stars and the moon, and, in a few months’ time, the sun. Clouds. Aeroplanes. But not…

He’s a common-sense kind of guy. There’s no such thing as UFOs.

Then he remembers. It was a TV show. The documentary said it’s only a matter of time before a comet will strike the Earth. When that happens, it will cause a new Ice Age, because the dust that will be thrown up into the atmosphere will be enough to block out the sun. Everything will die.

Except for him, it seems.

Even so, it’s hard to imagine that someone sitting only half a metre west of the impact might survive while everybody further away perishes. Though there are no immediate signs of life, he is convinced that, somewhere in the village of Hurmevaara, someone is tucking in to a cold-meat sandwich right this minute.

So it can’t be a comet.

But it has to be something along those lines. He can’t remember the word. And it’s cold now. Neither the liquor nor the thought of death seem to warm him any longer.

His phone should be in the zipped breast pocket of his jumpsuit, but it isn’t there. He set out to die, not to make telephone calls. All of a sudden the full force of his inebriation hits him.

Where is the nearest house?6

He remembers.

It’s three kilometres away. But that’s one house to which he will never return. The next one is a kilometre further.

He sets off on foot. After walking a few hundred metres, he comes to a halt. He digs his hands into the snow, washes his face. It feels necessary. The snow-rinse aches, freezes his fingers, numbs his face. But it cleanses him, purifies him in some important way. He takes another few steps, then stops again.

He turns, looks first at the car, then up at the sky.

What was that?

PART ONE

THE SKY CAVES IN8

1

‘And do you know what happens then?’

Throughout my time as pastor in the small parish of Hurmevaara – a year and seven months today – this same man has reserved every conversation slot that has become available. On the reservation slip he even writes that he specifically wants to talk to me, Pastor Joel Huhta. The reason for this is still unclear.

The nature of these pastoral conversations remains the same, however. Only the angle changes.

The man scratches his chin. The stubble is spread unevenly across his cheeks, and in some places is so thick that his fingers come to a halt. His eyes are blue and bright, but with no hint of joy. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the nature of the topics he raises, session after session.

‘I’m not a very good fortune-teller,’ I tell him.

The man nods.

‘But the UN is,’ he says. ‘I’ve looked at their most recent report on population growth. The human population of the Earth is around 7.6 billion. By 2030 – so basically in no time at all – it’ll be 8.5 billion. In the middle of the century it will already have grown to 9.7 billion. And by the end of the century – what do you know? – there will be 11.2 billion of us. And this is only what they call a medium variant. “So what?” you might say…’

I don’t say anything. Silence sighs through the parish building. We are in the south-eastern corner of the building, in a room with Venetian blinds drawn across the windows. Without looking outside I know that the late afternoon beyond the blinds is dark, and that there’s finally plenty of snow. The late arrival of winter and the as-yet-unfrozen waters of Lake Hurmevaara made me only a moment 10ago doubt my ability to read my diary. The room’s interior is austere, its low tables and thick rugs lending it an almost Japanese feel. Naturally we are sitting on chairs and not rugs, but there are only two of them and the room is about twenty square metres in size.

‘And what happens then?’ the man continues, his voice as bright and joyless as his eyes. ‘In Finland there might still be five and a half million of us, but what if there isn’t? The population of Africa is set to quadruple by the end of the century. Right now there are just over a billion people in Africa, and by the end of the century there will be four point five billion. That’s four times as many as now. At the same time there’s less water and not enough food to go round. Are people going to wait around until their hunger and thirst get even worse? The average African woman gives birth to about five children. Let’s imagine that by the end of the century one in five of them decides they’ve had enough of hunger, poverty, war and drought. One in five decides to up sticks or is sent away to make a living in better conditions. Let’s assume there’s an element of natural depletion and only one in ten leaves, then let’s assume only one in twenty makes it all the way. That’s a modest estimate. But still. If we take a slightly longer timeframe, let’s say until the end of the century, to bring in new generations, then we drop the number that make it all the way to Europe, by this point we’re only talking about two and a half percent of the four point five billion. How many people do you think that makes? One hundred and twelve and a half million. Where are we going to put them? Where will they settle? In what kind of conditions? And who’s going to agree to it all? That’s the equivalent of the 2015 immigrant crisis times a hundred and twelve. And that’s a low estimate, because it doesn’t factor in the millions and billions of people who will be born and die during that timeframe. It’s just a figure at a random point in the future, four point five billion. Plenty of things will happen along the way, as history tells us and as the future will show. People are always being born, dying, moving on, having children. Gifts from God.’

The man looks me in the eye. He couldn’t possibly know. Of course he couldn’t. I haven’t told anybody. Anybody at all.11

‘The Lord alone knows,’ he continues, ‘I’ve done my bit – before my divorce, mind. But that’s another story. I’m an engineer and I’ve got a thing for mathematics. I don’t daydream; I don’t make things up – I couldn’t. I make calculations. Every one of them shows that the world is going to end.’

Yes, apparently at the same time almost every afternoon, I think.

‘And,’ he continues, ‘if we live in a world that, according to all the demonstrable facts, is going to end – and pretty soon – then, well, there’s no hope.’

I don’t know why the man visits me. One possibility is that he simply wants to bring me over to his point of view. It’s understandable; it’s human nature. Surrendering to the certain destruction awaiting us must be more pleasant in good company. By yourself everything seems bleaker and more difficult, and it appears the same applies to the end of the world. And when no one else will listen to you, the local pastor has a duty of care.

‘You can learn to hope,’ I say.

‘But why?’

‘One answer might be that we can use hope to help us do our best for others and ourselves.’

‘One answer?’

‘I don’t have all the answers.’

‘Soon I guess you’ll tell me God has all the answers.’

‘That depends a lot on how you see things. Our time here is almost up.’

‘That’s what I’ve been trying to tell you.’

‘I mean our session. It’s almost four o’clock.’

‘I was only just getting started.’

‘Everybody has the same amount of time,’ I say. ‘At these sessions,’ I add, to avoid confusion.

The minute hand of the clock above the door edges across the number twelve, shudders, seems almost to flinch at the straightness of its own back. The hour hand is pointing to four. The man doesn’t move. There’s a question on his lips. I can see it before he opens his mouth.12

‘What do you think about the meteorite?’ he asks.

Six days. Six meteorite-filled days. Six days and nights during which the people in the village have spoken of nothing else. Meteorite this, meteorite that.

‘I haven’t given it much thought,’ I say.

It’s true, even though I am a member of the village committee, which will take responsibility for security at the War Museum while the meteorite is stored there for a few more days. The rock will then travel to Helsinki and from there onwards to London, where it will be taken to a laboratory to be examined. Security at the museum is being overseen by a group of volunteers, because the village cannot afford to hire a private security company and the nearest police station is ninety kilometres away in Joensuu. I have spent one night on watch at the museum, but even then I didn’t really think about the meteorite. I spent half an hour reading the Bible, and the rest of the night with James Ellroy.

‘It fell out of the sky,’ the man says.

‘That’s where they normally come from.’

‘The sky.’

‘Up there.’

‘From God.’

‘I’m guessing it’s more from outer space.’

‘I can’t make you out.’

Evolution made me like this, I think, but I don’t say it aloud. I don’t want to prolong the situation.

‘It’s four o’clock.’

‘Tarvainen says the meteorite belongs to him.’

Half the village thinks the meteorite belongs to them. Tarvainen was driving a car that technically belongs to Jokinen, on land that definitely belongs to Koskiranta, with petrol bought at Eskola’s garage, then headed to Liesmaa’s house where he made a call to Ojanperä, who arrived at the scene with Vihinen, whose delivery company, Vihinen & Laitakari, is in fact run by Mr Laitakari but half owned by Mr Paavola. And so on and so forth.13

‘Well, it really is already four, so…’

‘They say it’s worth a million.’

‘It might be,’ I say. ‘If it turns out to be as rare as people have been speculating.’

The man stands up. His steps towards the door are so hesitant that I find myself holding my breath. He reaches the doorway, manages to pull down the handle.

‘I didn’t even get round to talking about second-stage Ebola.’

‘Godspeed,’ I say.

Once I am alone, I open the blinds. The darkness behind the window looks almost like water, so thick that you could dive into it. I’ve been listening to people all day, and every one of them has mentioned their children. For a while – until today – I’ve managed to forget about the subject, and find a bit of peace and quiet.

My big secret.

‘Conflicted emotions’ doesn’t seem to cover it.

I listen to other people’s secrets as part of my work, but all the while I’m carrying the greatest secret I can imagine. And still I haven’t been able to tell Krista the true nature of the situation. It’s not as if either of us has forgotten that I stepped on a mine, a homemade nail bomb, during my deployment to Afghanistan. What I haven’t told Krista is that by doing so, I lost the ability to have children. That while everything looks and works the way it should, while the surgeons successfully put everything back together, I was left with a blackspot. One that is permanent, incurable, unfixable.

Krista.

Seven shared years.

Right from the beginning, Krista took, and continues to take, such good care of me in so many different ways.

And Krista’s most solemn wish? To start a family with me as soon as I returned from my secondment as a military chaplain.14

At first I avoided telling her, because it felt like yet another explosion. I’d already survived one, but I didn’t know if I’d be so lucky second time round. And now time has passed, and the longer I leave it, the more difficult setting off another bombshell seems. My wounds from the previous one were superficial – I’ve largely forgotten about them in my day-to-day life. Another explosion would send us back to square one. And probably further still – perhaps to a situation I thought I’d put behind me: a life without Krista.

I don’t want to think about a life like that.

And, of course, I’m carrying another secret too. Doubt. For what kind of God thinks this is good and acceptable, yet allows all the evils I have seen? I have asked God these questions, and I realise the paradoxical nature of my actions.

God, meanwhile, has remained silent.

I swap my trainers for a pair of winter boots, shrug on my eiderdown jacket, a thick red scarf, pull on my woolly hat and gloves, and leave. The crisp snow crunches beneath my feet as I walk through the centre of the village: Pipsa’s Motel, Mini-Mart, the Teboil garage, the Golden Moon Night Club, Mega-Mart, Hurme Gear, Lasse’s Bar, the Co-op Bank, Hirvonen’s Auto Repairs, and the Pleasure Island Thai massage parlour. Then, at the end of the perpetually deserted main street, the Town Hall and the War Museum. In the museum car park, cars with their motors running, red rear lights gleaming like pairs of sleep-deprived eyes. Villagers filled with meteor-mania. And, of course, members of the village committee.

I am about to turn onto the street where we live when I recall the confusion regarding yesterday’s security shifts.

I walk towards the museum. A large SUV with two men sitting inside is driving towards me. The driver is short and not wearing a hat. In the passenger seat is a man who can only be described as a 15giant. He fills half of the vehicle. The car has Russian plates. This afternoon’s fresh snow billows up and dampens my right cheek.

Four men are having a meeting in the car park. I recognise each of them even from this distance. Jokinen: a storekeeper whose acquisition methods remain unclear. Sometimes I get the sense that his yoghurts come from somewhere other than the wholesalers, and the meat he sells tastes fresher than anything I’ve ever bought at the meat counter in the local supermarket. Turunmaa: a farmer who deals mostly in potatoes and swedes, who dabbles in a bit of sprat fishing, and who owns so much forest he could form his own country. Räystäinen: mechanic and owner of the village gym, a man with a passion for bodybuilding, who insists that I too should take out membership of his gym and start working out properly. I have natural shoulders, apparently, and almost no fat to burn off. Then there’s Himanka: a pensioner, a man who looks so old and fragile that I wonder whether he should be out in temperatures this cold.

The four men notice my arrival. The conversation instantly dies down.

‘Joel,’ says Turunmaa by way of a greeting. He is wearing a furry cap and a leather jacket. The others are wrapped in quilted jackets and woolly hats.

As usual, Turunmaa seems to be leading the conversation. ‘We’re having a bit of a pow-wow.’

‘About what?’

‘Tonight’s guard duty,’ says Räystäinen.

They fall silent. I look first at Jokinen.

‘I have to Skype my daughter in America,’ he says.

‘What?’ asks Himanka, shivering with cold.

I look at Turunmaa.

‘I want to watch the match,’ he says. ‘I’ve got a tenner on it.’

‘That time of the month, I’m afraid,’ says Räystäinen. He has a frankly astonishingly young wife, and they are doing exactly what Krista wishes we were doing: making vigorous attempts to start a family. I know this because Räystäinen has regaled me with the fine details.16

I don’t even consider Himanka an option.

‘I’ll stand guard tonight,’ I say.

Houses line the street at irregular intervals, and the lights are on in almost all of them. Round here people go home early. In Helsinki the lights go on around six o’clock in the evening; here they flicker into life after three. Another car drives past, and this time I recognise the driver. The dark-haired lady often sings at the Golden Moon. She gives me the same look she always does. It’s not especially warm. In fact, it seems to say more than simply, you’re in my way. She is smoking a cigarette and talking to the man sitting next to her. They pass me and continue driving towards the museum.

I turn at the junction, and I can already see the lights. I walk for another four minutes or so, then step into the garden.

I knock the snow from my shoes against the concrete steps of our rented detached house. Opening the front door, I can already smell the cabbage rolls. I slip off my shoes, take off my outdoor clothes and walk inside.

Krista is in the kitchen, standing with her back to me, cooking dinner, just as she has done innumerable times before. The love of my life, I think automatically. What would I have if I didn’t have you? The familiar thought echoes through my mind, curling and swirling; it’s done that a lot recently.

I give her a hug, press my nose into her thick chestnut hair and draw the smell deep into my lungs. I see her long, thin fingers on the chopping board, in her left hand a plump red tomato, in her right a shining kitchen knife.

‘I’m going to be on guard duty tonight,’ I tell her.

‘I’m pregnant,’ she says.

2

Perhaps the nocturnal War Museum, devoid of people, is the right place for me right now. Old weapons, uniforms, recoilless rifles, helmets, grenades, a cannon. Historical maps and demarcation lines. Images of famous local battles.

I’m not in the best spiritual place, as they say. I’m about halfway through the night’s guard duty.

I walk around because I simply can’t sit still, and I can’t concentrate enough to read. The Bible seems to be accusing me of something, and in some inexplicable way I feel it should be the other way round. And the stifling heat of Ellroy’s Los Angeles seems too far removed from where I find myself right now: Eastern Finland, in the centre of the remote village of Hurmevaara. Only twenty or so kilometres from the Russian border. It’s –23°C outside and it’s the middle of the night, the time approaching 2:30 a.m. I realise I’m thinking that if God had a back, he turned it on me some time ago.

I arrive at what’s called the Long Hall and come to a halt by the meteorite – a chunk of black rock that has come hurtling through space, and that’s exactly what it looks like.

I remember the facts listed in the local paper. Initial tests suggest that it might be an example of the extremely rare iron meteorite; and the thing weighs about four kilos. It contains large amounts of platinum metals. Only a handful of similar meteorites have ever been found. Of those, one – a lump of rock that came crashing through the roof of a sports hall in the United States – was auctioned off in small pieces. The price per gram of meteoric rock can reach 250 euros. The fact box at the bottom of the article calculated that, if the Hurmevaara meteorite were to be sold off by the gram, it could be worth up to a million euros.18

Only a few more nights in Hurmevaara, I think as I stare at the black lump.

As for me…

I left the house as soon as was feasible. I absorbed Krista’s news, hugged her, gave her a kiss. I listened as she told me a thousand times how much she loved me and gushed that finally we would be a family together. When I finally regained my composure, and when Krista specifically asked me, I assured her I was so very, very happy.

Krista is pregnant. She is sure, she tells me, because she’s taken three separate pregnancy tests. I’m sure too. I’ve been through dozens of clinical tests with numerous specialist surgeons, and I cannot have children. And because I find it hard to believe in the virgin birth, the only option left on the table is that someone else has put the bun in her proverbial oven. And that someone must be a person capable of producing viable sperm.

A man.

This fact is even harder to understand than the pregnancy itself. When was Krista ever anything but good to me? When had she ever told or showed me she was unsatisfied? When was the last time even half a day went by without her saying (and, through the little details of her behaviour, demonstrating) that she loved me and me alone? And had a single night gone by without us falling asleep in each other’s arms, she curled in the crook of my arm, her left leg over my legs and her left arm across my chest?

A man.

My throat feels tight. There’s a gnawing feeling at the bottom of my stomach. Black electricity courses through my head.

Of course, I could hardly say congratulations, then ask who’s the father. I couldn’t. I simply … couldn’t. If I did that, what would happen? Would Krista run off with said man? Raise the child alone? On top of that, I would have to admit that for two years and four months I’ve been keeping a secret that would have had an inevitable and irreparable effect on our relationship.

Whatever the outcome, I would lose her.19

And life without Krista – I still don’t want to imagine such a thing.

The meteorite is displayed at waist height in a glass cabinet. It has been travelling for billions of years and crossed billions of miles – and here it is.

I look up. Identical glass cabinets run the length of the long, rectangular space. The faint night-time light casts a dim glow across the room; it seems the museum is saving electricity as well as security costs. Movement makes me feel slightly better, remaining on the spot is stifling, so I walk along the row of cabinets and stare into the vitrines without really registering what is inside them. Of course, I know without looking; my military background means I feel an almost personal attachment to each of these items.

At the end of the row I come to a halt; I’m not sure what I’ve just heard.

It’s hard to say anything specific about the sound, or whether I really heard it in the first place. It is very faint – vague and distant, bringing with it echoes of a distant thud, the sound of something smashing. I wait for a moment and try to make out what it might have been. I can hear nothing.

I move to the doorway of the Long Hall, switch off the lights and listen closely. It’s as though some sort of sound is coming from the other end of the museum. Two or three rapid steps, perhaps. The other end of the museum is kept dark all night. I move quietly, slowly, and arrive in the lobby. The lobby is set slightly higher than the exhibition rooms, and in the middle of the ceiling sits a glass pyramid skylight, which lets in water and isn’t strong enough to hold the weight of the snow. As I try to listen more closely, I smell something.

A scent, new and powerful, surrounds me. Here in the museum at this time of night the sensation is so unexpected that it takes me a moment to understand what it is.

Perfume.

A woman’s perfume. In the middle of the nocturnal lobby. It seems impossible.

I look towards the entrance. The table and chair set out for the 20security guard are in their rightful places, as are the Bible and Ellroy, there on the table. Next to them is my phone. The floor lamp, which I’ve moved near the table, makes the surface of the table gleam and casts a golden semi-circle on the laminate flooring. Again I hear a sound at the other end of the museum.

This time I can clearly make out footsteps. Then I sigh. Of course. The cleaner.

We’ve been having problems with the museum’s cleanliness and we’ve hired someone who cleans in addition to her own shifts at a paper factory near Joensuu. She cleans at the museum whenever she gets a chance, so it seems she’s made it here in the early hours. But there’s still something surprising about the perfume. That, and the fact that she is working in the dark.

I hear the footsteps again and walk towards her. I arrive at the doorway, and I am about to enter the room when something heavy strikes the side of my head just above the ear. I stumble, almost fall over, but it’s only after the second blow that I lose consciousness. I collapse on the floor.

I hear the sound of smashing glass, running feet. More glass smashing. I was only fully unconscious for a brief moment. Someone runs past me. It’s not the first time in my life I’ve experienced something like this. It feels much like being caught in an ambush. And it’s not hard to guess what the intruders are after; the museum is currently home to a meteorite worth a million euros.

It sounds like the running feet are making their way to the far end of the museum. I stagger to my feet and run after them. I can see a beam of torchlight up ahead. My head hurts; I can feel blood trickling past my ear.

I see someone clambering through a broken window and out into the starlit night. Arriving at the window, I see two figures dressed in black trudging through the snow under the gleam of the stars. I jump after them and immediately fall to my knees in the cold snow. My head is still reeling from the blow. The two make their way through the snow. Again the smell of perfume.21

I am already running through the snow when I become aware of two things: my own inadequate attire and the direction of the pair of intruders. They are heading towards the edge of the woods, and behind the half-kilometre strip of woodland runs a highway. There’s no way the pair are going to hide away in the small woodland; they must have left their get-away car near the highway. I turn and run towards the car park, pulling the keys from my pocket. If I turn back now, the thieves will almost certainly get away. The only option is to catch up with them, see what they look like. Perhaps even more. I’ve been in worse situations. I can’t help but think that this had to happen on my watch.

Their plan is a shrewd one. In order to reach the section of the highway, where I assume their car is waiting, I’ll have to drive the long way round. I’m going well over the speed limit. Our small, economical Škoda isn’t used to this kind of speed. I let out a frustrated roar as I realise my phone is back at the museum, next to my books, illuminated by the lamp.

It’s now even more vital I catch up with this pair of crooks.

I turn onto the highway and put my foot down on the accelerator. Almost nothing happens. The Škoda’s acceleration is slow at the best of times, so perhaps it’s too much to expect a record-breaking performance at this precise moment. I arrive at the spot where I guess their car must be parked. This is the most probable location: from here, there’s a path leading through the woods directly to the museum. I see damage in the snow verges, footprints. I continue driving. So far they haven’t come towards me, so the only option is to continue straight ahead. I can’t remember how far this road stretches before the next turn off. Far enough.

I take a tissue and wipe the blood from around my ear, and as I do I see a set of red lights ahead of me. I keep the accelerator pressed to the floor and catch up with the car in front one metre at a time. It disappears round a bend, but soon comes back into view. The car appears to be travelling at quite a speed – and why wouldn’t it? There are no police round here. The only risk is encountering an elk 22on the road, but if an elk crashes across your windscreen it doesn’t matter whether you’re driving at eighty km/h or at 130; the effect is the same.

We drive like this for twenty minutes. Then I lose sight of the lights altogether. I come out of a bend and the road straightens up ahead, and I find myself alone in the nocturnal emptiness. The road ahead is so long, the car in front simply cannot have reached the end and disappeared.

There is only one small lane leading off the main road. I turn and see the tyre tracks. The narrow lane soon turns into nothing but a trail. It’s hard going for the little Škoda. I assume I’m nearing my destination. I turn off the headlights and steer the car onto an even narrower pathway. Judging by the depth of the snow, it must have been ploughed about a week ago. A moment later I stop the car, switch off the motor. Then I step out and listen.

The sound of an engine. Light flickering between the trees.

3

The car is parked in front of a cottage, its engine still running. The headlights illuminate the front of the cottage like a set of spotlights. The cottage is small and run-down. It looks like so many of the old houses round here. The original occupants die and their descendants or distant relatives now spend a week or two at most in the house in the summer – for a couple of years. Then even that comes to an end, and, overwhelmed by the weather and the passing of time, the house starts to subside, like someone losing their grip on a lifebuoy.

I watch the cottage, the car and the two people from the side, like a theatre performance.

The pair are wrestling in the snow between the car and the cottage. No. It’s not really wrestling. One is punching the other, and the other is unable to fight back. The thuds of the punches and the possible shouts that follow are drowned by the sound of the engine. I creep a short distance forwards through the snow between the tree trunks, and from there I’m able to walk along the tracks left by the tyres. I’ve had close combat training, and I know more than just the basics of self-defence. I try to recall everything I’ve learned as I approach the pair.

At the same time I remember why I’ve come out here. I’ve been humiliated enough for one day.

Jeans, a jumper and a flannel shirt are, of course, relatively light attire for such biting cold, but I don’t plan to hang about. I approach the light-blue Nissan Micra; the smell of exhaust fumes is heavy in the calm, starlit night. Rust has eaten away at the rims of the bodywork. I look at the registration number and commit it to memory. I creep behind the car and look for a suitable route. One of the thieves is lying face-down in the snow. I can deal with him later. The other one walks up to the cottage door, unlocks it and steps inside.24

I wait for a moment then step out from behind the car and trudge through the snow towards the cottage. I pass the guy lying in the snow on his right side, still keeping my distance. I keep well out of the light, just in case the guy inside glances out through the window. For a split second, I think I see the thief in the snow moving, but perhaps not. The car’s headlights are so bright that I can see a long tear in the right sleeve of his jacket, and in that tear is something dark and wet. Maybe he cut his arm climbing through the broken window at the museum. Beside his left arm is a torch standing almost upright in the snow. I can’t help thinking that this is the object that caused the lump above my ear.

The car’s lights have been left on for a reason – I assume there is no electricity out here. There are two windows at the front of the cottage. In the left-hand one I see a human shadow passing between the floral curtains. I step nearer the door. I know what I’ve come to find. I reach out towards the handle.

Then the world suddenly bursts into flame.

And the door comes flying towards me.

If the snow beneath you feels soft and good, it usually means it’s too late. I know this, but still I enjoy the sensation. Lord knows I need some rest. Or does He? Is there a Lord at all? I open my mouth, snow falls inside. I realise I’m not on a couch or in bed, not discussing what you might call life’s bigger questions. I’m lying in the snow, and I have to get to my feet. I must get up, otherwise I’ll freeze. I have to get inside. Then I remember where I am.

I was about to go inside…

The cottage…

Smoke and dust are billowing from what used to be the windows. The remaining shreds of the curtains dangle round the window frames.

All this I see in the light of the moon and the stars. The Nissan 25Micra has disappeared. So has the thief who was lying in the snow. I finally haul myself to my feet. I look around, shivering with cold. Beside me, a few metres from the doorway, is the cottage door. I can’t hear anything. I can’t see anyone. There is a trail in the snow, drag marks. And there’s a torch propped upright. I pick up the torch and stand in front of the cottage.

I take a cautious step inside, flick the torch into life and allow the beam of light to wash across the interior of the cottage. I have seen many rooms, apartments and houses just like this. I look in front of me, stepping carefully through the debris. This space was clearly once a combined kitchen and living room.