6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

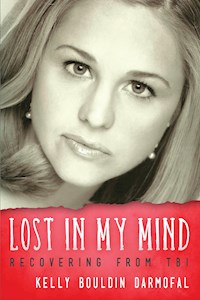

Lost in My Mind is a stunning memoir describing Kelly Bouldin Darmofal's journey from adolescent girl to special education teacher, wife and mother -- despite severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). Spanning three decades, Kelly's journey is unique in its focus on TBI education in America (or lack thereof). Kelly also abridges her mother's journals to describe forgotten experiences. She continues the narrative in her own humorous, poetic voice, describing a victim's relentless search for success, love, and acceptance -- while combating bureaucratic red tape, aphasia, bilateral hand impairment, and loss of memory.

Readers will: Learn why TBI is a "silent illness" for students as well as soldiers and athletes. Discover coping strategies which enable TBI survivors to hope and achieve. Experience what it's like to be a caregiver for someone with TBI. Realize that the majority of teachers are sadly unprepared to teach victims of TBI. Find out how relearning ordinary tasks, like walking, writing, and driving require intense determination.

"This peek into the real-life trials and triumphs of a young woman who survives a horrific car crash and struggles to regain academic excellence and meaningful social relationships is a worthwhile read for anyone who needs information, inspiration or escape from the isolation so common after traumatic brain injury."

-- Susan H. Connors, President/CEO, Brain Injury Association of America

"Kelly Bouldin Darmofal's account is unique, yet widely applicable: she teaches any who have suffered TBI--and all who love, care for, and teach them--insights that are not only novel but revolutionary. The book is not simply worth reading; it is necessary reading for patients, poets, professors, preachers, and teachers."

-- Dr. Frank Balch Wood, Professor Emeritus of Neurology-Neuropsychology, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 325

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

LOST IN MY MIND:

Recovering from Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Kelly Bouldin Darmofal

Modern History Press

Lost In My Mind: Recovering from Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Copyright © 2014 by Kelly Bouldin Darmofal. All Rights Reserved

Learn more at www.ImLostInMyMind.com

Published by Modern History Press, an imprint of Loving Healing Press 5145 Pontiac Trail Ann Arbor, MI 48105

[email protected] USA/CAN: 888-761-6268 Fax: 734-663-6861

Distributed by Ingram Book Group (USA/CAN), Bertram’s Books (UK).

First Printing: November 2014

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Darmofal, Kelly Bouldin, 1977- author.

Lost in my mind : recovering from traumatic brain injury (TBI) / Kelly Bouldin Darmofal.

p. ; cm. -- (Reflections of America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61599-244-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-61599-245-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-61599-246-1 (ebook)

I. Title. II. Series: Reflections of America series (Unnumbered)

[DNLM: 1. Brain Injuries--psychology. 2. Brain Injuries--rehabilitation. 3. Personal Narratives. WL 354]

RC451.4.B73

617.4’81044--dc23

2014020907

Cover photo by David Amundson of Superieur Photographics Oprah Winfrey photo courtesy of Salem College. Glamour Shots Inc. photo reproduced with permission. First Printing: November 2014

Praise for Lost in My Mind

“This peek into the real-life trials and triumphs of a young woman, who survives a horrific car crash and struggles to regain academic excellence and meaningful social relationships, is a worthwhile read for anyone who needs information, inspiration, or escape from the isolation so common after traumatic brain injury.”

Susan H. Connors, President/CEO,

Brain Injury Association of America

“Kelly Bouldin Darmofal showed me a world I had never experienced. Knowing the challenges, the strengths, and the perspectives that students with TBI bring to learning, I can be a better teacher for them. I admire what Kelly has accomplished in her life and her book. Anyone who cares about teaching and learning must read this remarkable story.”

Louann Reid, Professor and Chair, Department of English,

Colorado State University, and former editor of English Journal

“Lost in My Mind is an exceptional, heart-rending account of one young woman’s life suddenly transformed into a nightmare, and how she overcame it… a bright, happy girl who, in one night, sustains a Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) from a car accident, changing her life forever. Kelly Darmofal’s book is a triumphant example of how the human spirit can overcome life’s most serious challenges.”

Karen Ackerson, Executive Director of the Writer’s Workshop of Asheville, NC, and founder of the Renbourne Literary Agency

“I will never forget the day I sat in Biology class, tears in my eyes as the beautiful young girl stood in front of me telling her story of the car accident that almost claimed her life. I sat in awe as she talked about her recovery and her daily life, living with traumatic brain injury. Inspired by her strength and encouraged by her perseverance and determination, I had to meet this amazing girl! And she has been my best friend ever since!

I was a pre-medical student, struggling to pay for college, working full-time, and there were so many times I doubted myself, wanting to quit. Kelly would not let that happen. Kelly was there for me every step of the way, giving me encouragement, strength, and determination to never give up. Those same characteristics Kelly needed to survive and recover through her accident, she had given to me and made me who I am today. The story of Kelly’s tragic accident, her struggle through recovery, and her journey to succeed provides encouragement, motivation, comfort, and strength not only for families and victims of traumatic brain injury, but for all of us who have ever had an incredible dream.”

Dr. Amanda Waugh Moy, Emergency Medicine

“Kelly Bouldin Darmofal’s account is unique, yet widely applicable: she teaches any who have suffered TBI—and all who love, care for, and teach them—insights that are not only novel but revolutionary.

1. Poetry of art and science. With her occasional poems, she opens a window into her brain, revealing that language is sometimes at its best when brief, incomplete, and thereby widely evocative of experience that is irreducible to simple sentences. Her first poem after the injury—spoken impromptu—is a gift to literati and scientists alike, who will discover what they didn’t know about language and brain. Sometimes sardonic, often subtle, her rhetoric is life-giving as well as life-celebrating.

2. Theology. Like Job, she learned the hard lesson of a faith that ultimately made her both “thankful to my non-intervening God,” as she put it, and for that reason, resolute in becoming the person she now is. Her experiences exemplify that providence can’t be preached—to self or others—apart from persistent self-actualization.

3. Education. Warnings against inflexible educational bureaucracy abound in her descriptions of narrow-minded teaching. Yet, she recognizes good teaching so well that she becomes a teacher herself and models what all teachers must emulate: respect for students as persons in all their idiosyncratic potential. She understands mediocrity as the great millstone around the neck of education.

The book is not simply worth reading; it is necessary reading for patients, poets, professors, preachers, and teachers.”

Dr. Frank Balch Wood

(Frank Wood is professor emeritus of neurology-neuropsychology at Wake Forest School of Medicine and an ordained Baptist minister.)

“Kelly was referred to me by her neurosurgeon who happened to be a close friend of mine. His and her description of her traumatic injury and the tenacity with which she fought to regain basic functional abilities was impressive at that time. Her efforts since then should be inspirational to us all. In short, one cannot measure her attributes of determination and perseverance, spirit and courage, and willingness to embrace the whole of life. The result of her efforts speaks for itself.”

Dr. James D. Mattox, Jr., M.D.

Diplomate American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology

Dedication

I dedicate this book to my dear friend Britt Armfield, who died in a car crash in June 1993 and continued to speak to me, and to Matt Gfeller, who died of TBI while playing football in August of 2008. His motto was “I won’t let you down,” and he didn’t.

My story is also dedicated to Carolyn and Robert Bouldin—and especially to my patient husband Brad and to my son Alex, who have both provided the happy ending.

I have a dream

To race the lightning

To be the best

To race the wind

I have a dream

To race the lightning

And win!

(Kelly Bouldin, age 10)

Contents

Poems

Figures/Pictures

Foreword by Dr. David L. Kelly, Jr. M.D.

Preface by Carolyn Bouldin

Prologue by Kelly Bouldin Darmofal

First Memories (Recorded By Carolyn Bouldin)

Part One: Excerpts from My Mother’s Journal

Chapter 1 - The Incident

Chapter 2 - First Word

Chapter 3 - Choosing a Rehabilitation Center

Chapter 4 - Socially Inappropriate Behavior

Chapter 5 - Uncle Jimmy ‘93

Chapter 6 - Sophomore Year - ‘93-’94

Part Two: Kelly Speaks

Chapter 7 - Going Back to School

Chapter 8 - Returning to a New Place

Chapter 9 - College Bound (1996)

Chapter 10 - Psyched Out

Chapter 11 - Speaking and Acting Out

Chapter 12 - On My Own

Chapter 13 - Graduation and Employment

Chapter 14 - The Master’s Degree: Prognosis and Possibilities

Chapter 15 - The TBI Epidemic Rages On

Epilogue

Appendix: Study Guide and Activities

Acknowledgements

Resources

Bibliography of Influential Books

Recommended Readings

Index

Poems

Untitled (Mark Giordano)

Raindrops

The Meadow

Backward Time (for Kelly)

Someone

Again (handwritten draft)

Thunderbird

Birthday (age 9)

Albatross (oncet)

Memories (oncet)

Figures/Pictures

Split telephone pole (on left)

Get-Well card from friends

Cheerleading picture (August 1992)

Kelly - Portrait (age 14)

Letter from a friend (09/18/92)

Kelly after a makeover

Kelly’s first written sentence

Words that start with T, perseverance (Kelly writing)

Example of Kelly’s Spanish response in writing

Note from night nurse Pam Pyrtle

Carolyn and Kelly on the sofa

Kelly’s IEP with Word Banks

Britt Armfield, August 4th, 1976 – June 12th, 1993

Mary Chapin Carpenter poster, Community Living of Wilmington, NC

Oprah Winfrey, Salem College graduation 2000

Kelly five days after 9/11 at ARC (Winston-Salem)

Macy with her Ball-Ball

Kelly and her Mother attending the NCTE Conference, 2006

Foreword

This book should be required reading for people who have sustained significant head injuries and have neurological deficits and, also, especially for the families of those unfortunate individuals. This is the story of a young lady looking forward to her life with great hopes and expectations of success. She had many advantages with her family, position, and education. It is a compelling account of an individual with great determination, who gradually overcame, to a major degree, numerous struggles and frustrations that she confronted her through her recovery.

Her family’s support, understanding, and encouragement played a major role in her healing and were indispensable in shepherding her through this ordeal. She received excellent professional guidance; but it was her determination and focus that played the major role in her recovery. In the end, it is an uplifting and happy conclusion to a long struggle by a very fine lady. No two individuals with head injuries are alike because of the varying degrees of injury and their pre-injury personalities. Also, their support systems are unique to them.

I would strongly recommend this book to individuals with TBI.

Dr. David L. Kelly, Jr. M.D., Neurosurgery Chair Emeritus Wake Forest University

Preface

Memory is elusive even in the best of times. Kelly, who has a viable reason to have difficulty with recall, may be less guilty than I am, if errors have been made in Lost inMy Mind. In writing journals, I was simply trying to conserve memories for my daughter—the ones I knew she might need someday. Thus writing was both therapy and conservation. In my diaries (never intended for publication), some names have been changed in the interests of privacy; sentence fragments have been completed; and tenses and/or misspellings have been altered for clarity. We both apologize if our memory of data is flawed, and if anyone deserving is omitted from this memoir.

I always told my child that putting her life back together was like a difficult jigsaw puzzle; we would focus on her healing and accept the help of others—one piece at a time. I gave my writings to Kelly after her college graduation, telling her to abridge them at need, and omit anything others would find offensive. I thank her for accepting my gift of words, and for facing her mother’s personal angst. We’ve both given readers the truth as we knew it then and today, with no intent to belittle any organization or individual; our writings reflect the perceptions and fears we both experienced post-TBI.

Carolyn Bouldin

Prologue

A flash of pain shoots through my shoulder as I push my son’s stroller toward the park nearby—the price of motherhood, I think, and one gladly paid. My son, the lucky boy, looks like his father. I look like any typical mother, shoving an overloaded stroller uphill through a neighborhood filled with oak trees and “typical” young families, like mine. Looking at me, you probably wouldn’t guess I’m a survivor of TBI; that I’m disabled, often in pain, and that pushing a stroller represents a twenty-three-year victory for me—a survivor and mother, teacher, wife. I am happy today because I can push a stroller, because I can walk, and use two hands to type. The stroller, says my mother, is much like the walker I once used to relearn the skill of walking. I don’t, however, remember all the details of that journey, but I’d like to share what I do remember.

Come into my home. Look carefully at the Post-it notes scattered around my den. In the kitchen, you’ll notice a large chart noting, in bold black print, my son’s schedule for formula feedings, for naps, for solid foods. You’ll meet “the twins,” two rescue mutts who love me dearly. They don’t care if I can’t thread a needle, or remember exactly how old they are. We are much alike, happy in the moment, forgetful of earlier ones.

Does my Pomeranian mutt Mitzy remember the day someone set her on fire? No, Mitzy and I are good at suppressing bad memories. But I remember when my husband brought her home from a kill shelter. He saved her as he saved me. Some memories do last.

Do you remember where you were in 2000 as the ball dropped in Times Square? I have no idea how I welcomed the new millennium, or the make of the car I drove that year. Can I ask, “How did it feel when you had your first real kiss?” I wish I remembered my own. But I can’t even recall who my grade school teachers were, or what my prom dress looked like. Fragments of memory are all I possess of high school. Yet I will do my best to remember glimpses of my teenage years to help the reader fully embrace what it’s like to have TBI as an adolescent. My story really begins in 1992 after my traumatic brain injury. That was the year I didn’t die, but often wished I had. I now do research on TBI. I have lectured on the subject, and won a prestigious literary award for a TBI-inspired article in English Journal. Honestly, I’d rather not travel back to re-enter the torment of TBI convalescence. I don’t want to tell you how similar I was to the blind man who trips on a chair someone moved from its usual position. In my house, meticulous neatness is imperative. If you move my leather coat from a hook to the closet, I may forget I own it.

As I put my son down for his nap, I wonder if someday he will mind having a slightly different mother. It’s for his sake, however, that my TBI story needs to be told. Some tell me he is more likely to die from TBI than from any disease known to mankind. In 2014, posts the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there will be 2.5 million new victims of TBI. Not all will be soldiers and athletes—many will be children and teens. So, and I hold my breath, travel with me through a time more happily forgotten. I remember little of 1992, so my story begins with the unusual journal of my mother, Carolyn Bouldin. She wrote on greeting cards, hospital napkins, and a computer. She apologizes for any unintentional inaccuracies. This diary was written for me—if I lived and wanted memories—and not for publication.

To explain why I cannot personally write about ‘92, the following section is an example of my ramblings, which mother recorded three months after I was injured:

First Memories (Recorded By Carolyn Bouldin)

I’m very cold. And I’m very hungry. Mom is crying. Again. She looks funny crying, but I can’t laugh. I can’t cry, either. The kitchen isn’t very far, so I’ll make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich myself—bread from the basket, and LaLa’s strawberry jelly. I spread it on the bread myself, lots and lots of jelly. And I’m very cold. My sweater should be here somewhere. Look for the sweater.

Not on the chair and not in the hall. My bedroom isn’t very far. My robe is on the bed, so I put it on and look in the mirror. I look white. Mom says she is blue, but she looks pink. I can play the music myself: “I’m Alive” by Pearl Jam. Loud music now… good. Everyone says it is good to be alive, but what do they know? The phone never rings anymore. I just want to go outside by myself and take a walk and smoke a cigarette without Dad seeing me. I put on my shoes—tennis shoe on this foot, bedroom slipper on that foot. I can dial the phone and get someone to meet me. Mom is still crying. And she looks funny that way. I wish she would make me a sandwich. I’m so hungry.

My sister Tyler is talking on the phone. That’s why I can’t get calls from my friends. They came to the hospital because my mom said so. Tyler likes dogs but not cats. She says she does, though. She says they taste like chicken. Then she laughs. There must be a rule for what is funny, but I don’t know it. People laugh all the time, and I don’t know why. Maybe Tyler will cook me some chicken.

I think I was supposed to die on September 17th. But I’m going back to school instead. School will be better…

Kelly (December 1992)

Today it is hard to believe these were my actual words and thoughts. I’d think mother made this up if she didn’t hate lying more than she hates large crawling spiders.

Clearly I was lost in my mind, lost within my own body, and searching for a very long time. Surviving and recovering from a traumatic brain injury can be a surreal journey involving caregivers, families, both genetic and acquired, teachers, employers, therapists, pets, and children. Fortunately, my mother saved every napkin filled with notes, every medical report, and every report card from my various schools. “Saving them helped me believe you would live,” she says.

My story is at best a collage of recollections, most of which are accurate. It presents what I learned of life with TBI—a journey back from hell. I apologize for presenting early 1992 via my mother’s journals, but I need her memories. I tried to begin this memoir in 2002, but my lack of memory hampered any attempt for a second page:

As I begin to tell you what traumatic brain injury is like, please understand that I was in an automobile accident over ten years ago—September 17, 1992, to be exact. At 10:20 p.m., on a Thursday night. I cannot remember many details, so I must rely on my mother’s journals and the letters and notes of doctors and friends. I do know that my fifteenth birthday came and went five days before the accident, and that I had been in high school for just three weeks. This year of ‘92 was destined to be an incredible year. My sister Tyler was an ACC cheerleader at Wake Forest University, and I was a cheerleader on my high school Junior Varsity squad.

I was blonde, yet smart; flirtatious but not yet dating, as my parents were strict about my riding in cars with other teenagers. The football games I cheered for were on Thursday nights, which left the weekends open for following Tyler’s Wake Forest squad around the country. Study time was no problem, as I learned quickly in class and made my “A’s” with ease. A boy named Alex, who was a senior soccer player, was actually interested in me. And part of me hates to admit that as a high school freshman, I completely loved and admired my parents, Bob and Carolyn. Unlike most of my friends, I was rarely at war with the older generation. My mother was a high school English teacher who worked with the learning disabled. She understood teenagers better than I did at times.

Now I can’t remember what I wanted to say…

Part One: Excerpts from My Mother’s Journal

Part One: Excerpts from My Mother’s Journal (abridged) is a compilation of Carolyn Bouldin’s diaries and memories of Kelly’s convalescence, and is told in the mother’s voice.

On September 17, 1992, Kelly Vaden Bouldin left home to grab a Burger King chicken sandwich with friends. She was fifteen years old and quite hungry after cheerleading for the first JV football game of the season. Not allowed to ride with 16-year-old new drivers, our beautiful and talented Kelly left home with Zach, the 18-year-old son of family friends. She did not come home.

At 10:20 p.m., Zach turned his head to speak to Chad, a loquacious sophomore in the back seat. The road was curvy on Westview Drive near Kelly’s house, and the distracted young teenager drove directly into a telephone pole. The pole, unprotected by a curb, snapped in two. Kelly was in the suicide seat of the sturdy Honda Accord. Her seatbelt was fastened, but she had pulled out of the shoulder strap to shush the rowdy backseat passenger. Five days after her fifteenth birthday, three weeks after becoming a freshman at R.J. Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Kelly suffered a traumatic brain injury—a severe closed-head injury.

I had never heard of TBI, nor did I know it was the leading cause of death for children and young adults in the U.S. (Schroeter et al., 2010). This was a fact in 1992. It is true today.

In layman’s terms, Kelly hit the right frontal portion of her forehead on the dashboard of a car that severed the telephone pole. She had no other injury than a harsh blow to the head. There was no blood, yet Kelly was unconscious. The two boys were minimally affected, and they expected her to wake within moments. She did not.

Kelly was unconscious when a neighbor, Dr. Romey Fisher, pulled her from the Honda that had no air bags. She was flailing about, and had a seizure in the ambulance during the ten-minute drive to the hospital. Because she was struck on the right side of her forehead, Kelly’s brain had a whiplash reaction, causing injury and bleeding to the back left side of her brain. There was bleeding in the right frontal area of the impact, indeed in both frontal areas. Kelly also suffered brain stem trauma. She was hemorrhaging into every ventricle of her brain.

Split telephone pole (on left)

VIew of crash site from a vehicle

Thus only time would tell if my young child could awaken at all... or if she would remain in a PVS—permanent vegetative state —or die.

Kelly’s injuries were quite severe, and her father and I were told she might not last the night. I still hear the echoes of the emergency room receptionists: Does she have a living will? Is she sexually active? Why didn’t she have I.D.? Has she been exposed to HIV? “NO, NO, AND NO… she has never been on a date!” I know that any parent alive can imagine the pain and anguish that stole our daughter’s childhood.

Yet, on that evening in ‘92, Bob and I were waiting for Kelly’s return when the phone rang at about 10:22 p.m. Dr. Fisher, a close friend, advised us that our child was all right despite the fact that she and her friends had hit the telephone pole near his yard. My first statement was strangely calm, to the point: “Is she paralyzed, or blind?”

“No,” Dr. Fisher answered. “The biggest problem is that she is not awake… but she probably will be when you get to the hospital.”

She was not. Dr. Fisher had wisely, instantly sent Kelly’s ambulance to the major trauma center at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. The boys, both alert, were sent to another ER at Forsyth Hospital a few miles away. Had Romey made another decision, Kelly would probably not have survived.

My husband and I arrived at the hospital at about 10:45 p.m., parked illegally and flew inside. After we had answered a myriad of insurance-related questions, we were finally given our daughter’s medical status. Kelly had been placed in a medical coma, and her brain was heavily oxygenated to minimize brain swelling. A pressure monitor was inserted into her brain so that if too much swelling ensued, part of her skull would be removed to allow room for further expansion. Doctors informed us that Kelly couldn’t possibly awaken for at least three days. She registered a 5 on the Glasgow Coma Scale (8 or below indicates severe brain injury).

Oh, God! My child was now in the hands of strangers—strangers devoid of smiles. I was, however, oddly calm in the surreal environment of the emergency facility. I had stepped through the looking glass that separated the “normal” world from the world of those whose lives could never again be what they expected.

Soon Dr. Fisher arrived, having tended to the more minor needs of the car’s other passengers. He looked at me and wrapped me in a blanket, because I was entering a state of extreme and delayed shock. I was shaking; my teeth were chattering.

“Who should I call to come be with you?” he asked.

Winston-Salem had been my home for over 20 years. Surely I should call some friends. But who to call in the middle of the night, knowing Kelly might not live until morning. Who should be called to hold me if my child died in the night? I simply shook my head.

For some odd reason, I felt I had no right to call anyone. Such a terrible burden to share. Even my older daughter Tyler, a sophomore at Wake Forest University, shouldn’t be called until morning. She could have an accident rushing to the hospital. I felt I hadn’t the kind of friends I needed. I was numb. I didn’t want my minister with me to tell me of God’s mercies, or my parents, whose grief would make our tragedy more real. I lay beside my stunned husband on an inflated beach raft in the ICU waiting room, and existed in misery until morning, trying to imagine the woes of other mothers who had rested on that wretched plastic raft.

And I was so wrong about not calling friends. The daylight came, and Kelly was still holding on. At least sixty friends swarmed the ICU waiting area, holding me and talking to my husband, Bobby, bringing us coffee, food, strength. Kelly’s story was not in the newspaper on September 18th. I had demanded of the police to withhold a press release so that Kelly’s friends could learn about the news in a kinder way. But somehow they knew, and came by the scores. And they stayed. We laughed and prayed, and together we found the power to keep breathing, minute by minute.

Then another night came, and as our friends left, my strength waned, as if their leaving lessened Kelly’s strength as well. I can’t remember the second night.

The next day I turned to my best friend Ann Davis, and told her that I knew what would help me most. I couldn’t be strong alone. Ann is a former nurse, and she mobilized the friends I didn’t know I had.

Making a calendar of shifts (my treasured possession still), she kept someone with me every waking moment. Asking for this kind of help was so foreign to me, but I quickly learned that to survive the after-math of severe brain injury, my family would need a great amount of assistance. To obtain this level of support, I would have to ask for it, and others would be glad to give. I want to thank Ann, Barbara, Cynthia, LaLa, Diane, and all of the other names on that list of friends. I didn’t realize that you cared so much about my child, or me.

Get-Well card from friends

When Dr. David Kelly told me my daughter was still alive in the dawn of September 18th, I called my daughter at Wake Forest University. I told Tyler about the wreck without crying. I did not tell her on the phone how serious Kelly’s injury was. I informed her that her sister was in a coma, but that she would be okay. Kelly would probably be awake soon. I asked Tyler not to rush but to come when she could. And she did. My 19-year-old daughter was a sophomore at Wake Forest, a business major, a varsity cheerleader; yet here she was, holding me when I needed her. I met her new boyfriend. I saw him holding Tyler up while she cried uncontrollably. The boyfriend was holding Tyler up, and then she was holding me. “I’m glad he is here for her,” my mind said. She asked me what she could do and I spoke:

“Go back to school and live a normal life.... Don’t cancel anything. I need to know that one of us is living a normal life... I need something good to think about!”

That is what she did. Tyler kept cheering, making good grades, and visiting when she had moments to spare. I would learn later from her roommate, Julie Polson, how much Tyler cried, how devastated she was, and how difficult a time this was for her.

The Red-Haired Resident

On September 18th, my family was evidently assigned a social worker employed by Baptist Hospital. She appeared to be about twenty-two, and wore cute little suits in neutral colors. She came to see me and gave me a sideways hug.

“Mrs. Bouldin,” she said, “Are you feeling depressed?”

Astounded, I made some rude rejoinder like, “No, I love hospitals and I’m just waiting to see if my child will live.” Then I gave the polite response. “What do we need a social worker for?” I hemmed and coughed.

“Well, for whatever you might need,” she replied. “You might need a wheelchair to take home with you or a hospital bed, and counseling is avail…”

I told her to leave at once. My mind was unable to cope with the concept of wheelchairs at this point, but she kept appearing each morning, more regularly than the doctors.

“Mrs. Bouldin, are you perhaps a little blue today?” she would ask.

I left a call for Dr. Michael McWhorter, one neurosurgeon in charge of Kelly’s case, requesting that the social worker be removed from my life. And I couldn’t resist asking where this girl actually went to college. She never came back.

The red-haired resident doctor wasn’t as obviously objectionable. In fact, he was the first human being in the ICU to communicate with me in any depth. Surgeons are wonderful, but so busy saving lives that a resident generally appears to cover the chitchat, or at least this was our experience. This fellow told me calmly what to expect concerning Kelly’s prognosis. As if he were reading from a chart, he told me that she might not live. She might need a shunt in her brain if the pressure rose and needed relieving. She might live and remain a vegetable. Lastly, she might recover up to 90% of her former capacity, eventually. I could easily see that the resident felt this was the best-case scenario.

He then warned me that I must never, ever expect to regain the Kelly I once knew. At this point, I developed antipathy for this young well-intended person, who may have been correct except for telling me what never to do.

There is an absence of hope in such a place, an utter vacuum where dim rays of light should be allowed to survive. I will never know why I was constantly discouraged from having any hope.

Meanwhile my daughter continued to sleep.

As to the resident, he reappeared daily for about a week to remind me to keep my expectations low—until I asked Dr. McWhorter to send him the way of the social worker.

Both the social worker and the resident had good intentions. However, it was not their job to lower my expectations. Every janitor, nurse, volunteer in a hospital will take an interest in a coma victim, freely giving you advice about what to do, what rehab centers are best, and so forth. After listening to every positive word I could glean from anyone, I became inexpressibly confused. One of Kelly’s doctors then told me to pick one person to listen to and trust. So that is what I did. I also learned that you can trust yourself. Take the tidbits of good advice others offer, and avoid opinions that you haven’t the skill to assess.

Shearing - 9/19/92

I was told early on that Kelly had suffered from brain shearing. This phenomenon cannot be measured by an MRI. In essence, the tiny neurons that connect the brain with the spinal cord are too small to be seen on X-ray. These neurons suffer a whiplash trauma during brain injury. They are stretched or broken or twisted. When a child like Kelly is young, there is good chance for the neurons to reconnect, or to form new pathways for brain signals when old ones are severed. This is a primary reason doctors cannot predict the amount or recovery for a victim of TBI—some things aren’t measurable. I learned about phenomena like shearing from doctors, but mostly Kelly’s nurses helped me understand her wounds and symptoms.

Doctors alerted me to a TBI filmstrip being shown twice weekly, but I was always too busy helping Kelly to attend. So I asked questions all the time. The nurses were more helpful than the neurosurgeons, who were kind but often unavailable. These remarkable women and men were encouraging, explaining that the healthier and stronger Kelly’s body had been, the more likely she was to heal faster.... So all the years of soccer and dance and gymnastics could pay off after all.

Also, nurses and therapists were very alert to Kelly’s pre-wreck IQ. Evidently, the higher it had been, the more likely that she would “come back.” Again, I realized prior efforts like the frequent homework help from Bobby and me had not been wasted. Kelly might never make another A, but a solid student could get well faster—a probable IQ loss after a severe TBI might not prevent Kelly from having a meaningful future, some kind of a useful life.

Cheerleading picture (August 1992)

Kelly - Portrait (age 14)

Things That Helped (The First Three Days)

“Humor is the absence of terror, and terror is the absence of humor.”

– Lord Buckley

The ICU nurses requested pictures of Kelly, showing her as she appeared before the car crash, to be placed above her bed. They wanted to visualize the patient they were treating as a bona fide human being, not a swollen wreck victim. With the placement of those pictures, I knew that Alice, as well as the other ICU nurses, would labor to save Kelly’s life. When they combed her long blonde hair in neat French braids and requested double shifts to stay with her, I knew my daughter was in good hands. Kelly’s staff of nurses kept her looking lovely, which I appreciated more than words could express. They not only spent time arranging her hair, but also shaving her legs with lotion and trimming her nails.

A black sense of humor had developed in the ICU waiting room, as Bob and I sat with at least 50 of Kelly’s friends each day. Zach (who drove the car) and Chad (the loud passenger) were nursing bruises and cracked ribs, and they sat with our family and friends, waiting for Kelly to awaken. Another family, the Grays, was present in our area; they received dozens of phone calls. The phone was generally answered by whoever sat nearest, usually one of Kelly’s friends, and the questions reverberated, “Anyone here named Gray? Are you Mr. Gray? Is anybody present called Gray?”

“I’m black and I’m blue… but I’m not gray!” Chad replied each time. I’d believed I would never laugh again, but I fell apart giggling. Later, when Kelly began to awaken, and would thrash and kick male attendants between their legs, we all became hysterical. The nurses christened her “Longlegs.” Everything was so strangely funny—we allowed laughter to replace the tears everyone was afraid to release. Laughter is so good. It helps when nothing else can. I also recall laughing wildly when 14-year-old Carla discovered the doctors had to shave some of Kelly’s scalp: “It will kill her,” she hollered. Everyone laughed at the incongruity.

My closest friends, Barbara Price and Ann Davis, smuggled wine into a thermos and dragged me into a patio area to drink it. They actually made me laugh with their “chardonnay tea.” They even ordered pizza for friends in the waiting room. These were the friends who never left me alone. Ann continued her calendar of visitors, scheduling someone to stay with me for predetermined periods of time. This one act saved my sanity. Alone, I always imagined the worst. With others, I was forced to remain an optimist. Friends who cared were essential to me.

Several friends who were nurses, therapists, and doctors helped the most. They had the medical terminology to explain what was going on with Kelly (They know you, and tell you the truth).

Comfortable and clean clothing helped. Since I wouldn’t leave Kelly, I looked like a contaminated dirt lizard, and smelled like “hospital!” One friend, Ann Reagan, bought me two new warm-up suits. Wearing the new and clean clothes, I felt better, so I acted nicer to everyone.

Meeting mothers of persons with brain injuries, who had survived, helped hugely.

Going outdoors and looking at trees seemed to help my sense of permanence and stability. It felt like the trees were resting and waiting for Kelly to wake up.

Seeing the pressure monitor in Kelly’s head read at “2” helped (this was a very good, low reading). Nurses let me stay with her more than visiting hours allowed. They knew she might die. Those little minutes holding her hand helped me breathe in, out, in, out.... Each one mattered.

First Purposeful Movement - 9/19/92

The monitor was removed and Kelly tried to climb out of the bed. This was Kelly’s first purposeful movement, her third day in ICU. She was withdrawn from the medical coma that over-oxygenated her blood to keep the swelling in her brain down. This was both a horrible and wonderful day. When Kelly was removed from life support successfully and out of deep coma, we were warned that she might not move or breathe again on her own. Bob and I waited to see the look on the doctor’s face when he left us to withdraw supports. Our friends literally held us up for those seemingly endless moments. Then we heard laughter from beyond the door. A nurse rushed into the ICU waiting room to say, “She’s trying to climb off the table. That little girl wants to go home!”

Yet Kelly wasn’t really awake at this time. Her eyes were closed and she did not speak, but, hallelujah, she was strong enough to kick those strangers tying her with restraints to an unfamiliar bed.

Letter from a friend (09/18/92)

Day Four - 9/20/92

Kelly developed a staph infection at the IV insertion point on her right wrist. A lot of swelling… Kelly’s temperature rose to 105 degrees. She was now twice critical. I do not want to write about this irony, that we might lose her not to a TBI, but to infection. The ICU nurses didn’t immediately note the infection. Another visitor, Elizabeth (and another former nurse) lifted Kelly’s sheet and examined her IV lines. Elizabeth saw the red, swollen right arm, which had grown to the size of a football, and alerted the hospital staff.

Day Ten - 9/26/92

Too busy to write the past few days. Today Kelly was better and her eyes, her amazing eyes, were flickering open... shut... open... fever going down...

The Boy in ICU - 9/27/92

On Kelly’s 11th day in the Baptist ICU, she appeared to be napping. Earlier she’d been looking at me, and I had told and retold her about her accident, but it didn’t seem to register. My friend Margaret Mills, a former nurse, admonished me to talk to her constantly, because “people in a coma can hear you, even if they can’t remember what you’ve said.”

Taking Margaret’s advice, I talked and talked until no more words would come out. I played pop music, mostly Pearl Jam, for Kelly via earphones, hoping she could hear. Now Kelly was resting, and the boy in the bed next to her was, too.