Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

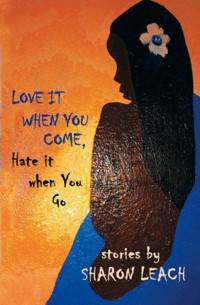

Sharon Leach's Love It When You Come, Hate It When You Go occupies new territory in Caribbean writing. The characters of her stories are neither the folk of the old rural world, the sufferers of the urban ghetto familiar from reggae, or the old prosperous brown and white middle class of the hills rising above the city, but the black urban salariat of the unstable lands in between, of the new housing developments. These are people struggling for their place in the world, eager for entry into the middle class but always anxious that their hold on security is precarious. These are people wondering who they are - Jamaicans, of course, but part of a global cultural world dominated by American material and celebrity culture. Her characters - male and female - want love, self-respect and sometimes excitement, but the choices they make quite often offer them the opposite. They pay lip service to the pieties of family life, but the families in these stories are no less spaces of risk, vulnerability, abuse and self-serving interests. Sharon Leach's virtue as a writer is that she brings a cool, unsentimental eye to the follies, misjudgements and self-deceptions of her characters without ever losing sight of their humanity or losing interest in their individual natures. The beauty of her writing is its ability to marry the underlying muscular deftness of her prose with the voices of her narrating characters and the variety of registers they speak. She writes about the pursuit of sex, its joys, disappointments and degradations with a frankness little matched in existing Caribbean writing.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 291

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LOVE IT WHEN YOU COME,HATE IT WHEN YOU GO

STORIES

SHARON LEACH

First published in Great Britain in 2014

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

© 2014 Sharon Leach

ISBN 13 (PBK): 9781845232368

ISBN 13 (Epub): 9781845233273

ISBN 13 (Mobi): 9781845233280

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form

without permission

CONTENTS

Fifteen Minutes

Mortals

Lapdance

The Private Lives of Girls and Women

Independence

Comfort

Falling Bodies

Love Song

Smoke

A Mouthful of Dust

All the Secret Things No-one Ever Knows

Love It When You Come, Hate It When You Go

Acknowledgements

For Mummy

We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love, but always meeting ourselves.

— James Joyce, Ulysses

FIFTEEN MINUTES

An agent was the only way to go, for bookings and everything else. All the big stars had agents. Even the no-name ones. She would become a big-time Hollywood star; she’d always dreamed that. Right now, talk shows were interested. That was fine. But that was just the tip of the iceberg; she craved more – celebrity product endorsements – hell, maybe even national ad campaigns for make-up, perfume, lingerie. Fast food, well, that was iffy – depended on what kind – nothing greasy and disgusting – her skin, even at her age, was prone to acne breakouts. No biggie. She was up for anything. How did that saying go? The world was her oyster and this was the land of opportunities. For now, she would work with TV – until she could reposition herself for the big screen. All she needed was a foot in the door. In the meantime, TV. She’d worked hard with a trainer to manage her weight so that she wouldn’t appear bloated – everybody knew TV added ten pounds. Right now, she needed a guest-starring role on a primetime show. Comedy or drama, she wasn’t fussy. Or, better still, a reality show. She wasn’t a fan but there was no denying those shows could lead to more, maybe to her own talk show. She was famous now. Well, almost. Almost famous. Ha ha. Like the movie. But look how far she’d come, from that shithole in Kingston. She had her daddy to thank for that. Thank God for DNA tests. Turned out that the man her mother had whored around with had, for whatever reason, filed for her and sent her to college. So far, she’d not managed to get out of that godforsaken North Carolina backwater, but one day everybody in Jamaica would know her name. Sheer luck had brought her to this point and she’d be an idiot not to capitalise on it. She would become a fucking celebrity. Another Kardashian.

She’d been invited to a few red carpet premieres. She’d begun to be recognised when she went out. Naturally, men had started coming on to her. She’d given head to more men in the last few months than at any other time in her life. Which said a lot since, unlike most of her girlfriends, she’d always liked giving blowjobs – most women were squeamish or they griped about jaw cramps. There’d been celebrities, too – a rapper (hitless since the 90s) who delighted in debasing her in countless ways; a famous television anchorman with a secret drug problem; a basketball star with the Knicks who was incapable of screwing her unless she dressed and spoke like a five-year-old; and a faded androgynous, middle-aged blonde R&B singer from the eighties intent on making a comeback.

But calls for bookings were slowing. She’d shelled out good money to hire an acting coach but where were the jobs? “Find me work!” she snapped at the agent, a nervous woman with big, stiff-sprayed hair. “Ah dat mi a pay you fo’”. Then, into the mist of incomprehension that hovered like a mushroom cloud, she clarified, “That’s what I’m paying you for. Isn’t it?”

“So... I can’t believe I’m here with you. You’re the It-Girl, y’know? Like Paris. Lohan...”

He was beautiful and slight – nobody, really. His name wasn’t a household one. But he was a model, and so he was loaded, at least on his way to becoming so.

“Yeah, well.” She sipped from an oversize glass of wine, and affected a bored posture.

“I’m serious. What you did was the coolest thing, ever! Saving that kid. And with you afraid of water. Diving in – that’s just awesome.”

She was touched by how sincere he was, and had to fight the urge to confess that rescuing the kid, Toby, who had dived, not fallen, into the pool, had been a buck-up. That he was really an eleven-year-old on his way to a serious drug problem, who had in fact been fleeing the dealer, who operated from the back of the Y, where she’d gone to buy a dime bag of weed. That, yes, she swam like a fish, and she’d never been afraid of water. That she and Toby had promised keep each other’s secret. But she bit her lip instead and continued to look bored.

She’d met the model the weekend before, at a party in New York. The week after she was on the west coast, visiting him. From where they sat in his darkened living room, the view was of mountains and sea. Behind them music quietly spilled out from his elaborate entertainment system, filling the room like a mist. They could see one of LA’s most intriguing sights: a Pacific sunset merging with the blanket spread of lights that flowed from the front steps right out to the sea.

“Where have you got to, leibling?” the model, a blue-eyed boy with bee-stung lips, originally from Frankfurt, asked, a frown in his voice. Then stretching, so that his incredible six-pack showed beneath his shirt, he reached over, took the wine glass from her, and set it down on the glass coffee table in front of them.

She smiled, lightly flicked his muscular arm. She could scarcely believe that she was sitting here in a living room almost overlooking Beverly Boulevard. Not bad, considering she’d met him only after being rejected by a man she’d been trying to snare at that party, an important East Coast man with connections to powerful movie directors. But this would do. She smiled at him again. Maybe it was even better.

Her agent said the phones had stopped ringing for her. “We knew it wouldn’t last forever, hon,” she said, patting her hand across the table. “This happens all the time. They give you your fifteen minutes, then they move on. They have incredibly short memories in Hollywood.”

They were at lunch at Second Ave Deli, a haunt of East Coast celebrities – bonafides and up-and-comers. Here, starlets brushed shoulders with A-listers, the beautiful anorexic set contemplated their plates of garnished celery sticks, and celebrities famous for being famous answered chirping cellphones and BlackBerrys.

She tapped her finger against her front teeth, distracted. Her agent wasn’t being truthful. She’d seen ordinary people turn their fifteen minutes of fame into a Hollywood career. That girl from Survivor, as a for instance, had got a gig hosting on The View with Barbara Walters. And why hadn’t she moved on that screenplay that guy had volunteered to write? Anybody could become a star. This was fucking America, wasn’t it?

Around them flatware clinked. They’d been there already almost forty minutes and still nobody had recognised her. Hoisting up her sunglasses onto her head, she looked around expectantly. Still nobody ventured over for an autograph, or to snatch a bit of food off her plate to sell on eBay.

“So, how’s model boy?”

“OK,” she said, staring out the window. The truth was model boy had dropped her shortly after they’d gone to a party in Beverly Hills and her name hadn’t shown up on the list.

“I need work.” She stared despondently into her matzoh ball soup. “I’d take a non-speaking role,” she said listlessly, turning to look at a man who sat scratching his nose and staring at her from a table across the room.

“Sweetie.” The agent spoke soothingly, looking up from her chicken salad. She had a face that seemed composed totally of contours and planes. Her lipstick had faded, leaving the faintest trace of lip-liner. “There’s nothing.”

“Kim Kardashian gets paid by the hottest club owners just to show up at their clubs. Lindsay Lohan –”

“Due respect, that’s Kim K and Lindsay L. A party girl and a Hollywood star. And let me tell you this. Their bubble will burst soon. Nobody’s hot forever.”

Why was the agent fighting her like this? William Hung was still milking his wretched Ricky Martin impression, still turning up on goddamned red carpets in Hollywood. She pushed the food round her plate, thinking maybe she should hit the gym harder.

“What about... you know, skin?”

“Skin?”

“I’m not above that. I just want to get out there.” She hated the ring of desperation she heard in her voice.

“T&A?” The agent gaped, unchewed food showing in her mouth. “Oh dear. You don’t want tits and ass. You’re better than T&A. You have a college degree, for God’s sake.”

“Don’t tell me what I want.”

She had the impression that someone was standing beside her. She looked up. It was the man who’d been making eyes at her from across the room. He was middle-aged, dressed untidily – his coat and sagging tweed pants had obvious tomato sauce stains – thin as a rail and sporting black-rimmed Coke-bottle glasses. His weak, watery blue eyes blinked slowly behind the thick lenses.

She perked up, passed her tongue over her teeth, in case there were lipstick stains, and smiled. She clicked through her mental Rolodex but didn’t recognise him. Still, he could quite easily be someone influential in show business, a director, maybe. When he hesitated, she licked her lips, got the taste of gloss on them.

The man looked quizzically at her. Sticking out her chest, she sighed, held out a hand for a pen and paper.

“I’m sorry,” the man said haltingly. “You seem, well, you look... Oh dear. I am sorry. I thought you were somebody.”

She couldn’t believe she was here. She looked around in awe, shivering slightly. The studio was freezing. She’d worn the wrong clothes, she realised in dismay – strappy spike heels and a frothy new gypsy dress that hung off her shoulders, beneath which she wore no underwear. But at least her new jewellery was blinging big-time. She’d maxed out her credit cards to deck herself out. Now she was broke. This was it. Her last shot at making the jump. She tried to ignore the ripple of cold that ran through her, hardening her nipples. She wasn’t complaining, though; a nationally syndicated late-night talk-show had finally called.

The show’s host had personally left her flowers, along with a polite handwritten note requesting that she join him in his dressing room after the show. For a blowjob? She made a mental note to get a commitment from him first; she’d been screwed over by too many people she’d given blowjobs and afterwards had nothing to show for it, except chocolates, a few pieces of jewellery and a pair of expensive shoes.

She thought about her idol, Mae West, and tried to channel her.

Interviewer: “Goodness, what jewellery!”

West (throwing back her head and laughing throatily): “Goodness had nothing to do with it, dearie!”

The show’s production manager was a nervous little man with headphones and a clipboard who’d been helpful in getting her situated. He poked his head around the dressing room door. “Knock, knock. Are we decent?” he asked.

She looked up, smiling crookedly.

“Comfy? Do you need anything at all? Good. Quick thing – you’re up right after the break,” he said, ignoring her fidgeting.

“Oh, I’m just nervous.”

“C’mon! Just look at that face. You’ll photograph well. Don’t be nervous.”

She checked her reflection in the mirror. “OK.”

“By the way, big show tonight.” Winking, he added, “Glenn Close. You’re in good company.”

Later, she wandered from the green room, waited in the wings and watched the show on a small monitor with the rest of the crew. She studied the star’s relationship first with the cameras and then the audience, which was enthusiastic, eager to see a famous person. She shivered with cold, scanning the audience for potential talent scouts. Her feet hurt in her ridiculous shoes. She stepped out of them.

At the break, the producer came to tell her that her segment had been shifted down to the final quarter of the show. “Don’t worry, hon,” he said, giving her arm a reassuring little squeeze. “You’ll get to tell your story.”

She stared at his retreating figure, stricken. When she went back to the wings, the crew were talking.

“It’s running overtime,” someone said.

“The last segment might get canned.”

“Might? Ten bucks says it’s gonna, for sure.”

“What’s her story anyway?”

“Saved a kid from drowning. Some shit like that.”

“Man, Glenn Close. Are you kidding me? Cruella Deville trumps kid-saving any day of the week.”

There was a flurry of activity behind the scenes, with people scurrying all around her. She felt as if she were no longer present, as if she were eavesdropping on a private conversation not meant for her. She waited, the sinking feeling in her gut becoming stronger with each passing segment of the show.

Then it was over. Glenn Close had left and the show was over. Connie stood shoeless, still in the wings, while the show’s theme song played. “That’s it, people!” someone shouted. “That’s a wrap.”

“Sorry, we ran out of time.” The producer approached her, shrugging. He was nibbling on a Granny Smith apple. The action of his teeth, which were slightly big, reminded her of a bunny gnawing at a carrot. “That’s show business for you. Sometimes things don’t work out.”

Then he was gone, and the crew was scampering about. She looked around. The host had finished shaking hands and signing autographs for the studio audience and was preparing to leave the room. She tried to catch his eye when he walked close by her. She smelt the musk of his aftershave and imagined what it would be like in his arms, beneath him in bed, the weight of his warm body gently crushing her. She angled close to him, touched his sleeve. She wanted to say, “Hi, it’s me. You don’t remember? You wrote me a nice note. You wanted to see me in your dressing room after the show.”

But the words remained frozen on her lips when he turned and looked right through her.

MORTALS

The baby’s cancer has come back.

Lisa watches the doctor’s mouth forming words, which she doesn’t hear, although she knows them all too well. It’s like watching TV with the volume down, only there is sound, a blur of noise around him, the normal sounds of the ward. Lisa continues watching him, dazed, her mouth slack, as if she’s in a dream. But it is no dream. After six months of cautious optimism and finally beginning to breathe again, Lisa feels a familiar weight settle in the pit of her stomach.

Then the volume seems to be turned up again and she can again distinguish his words, though not clearly, as if they are coming from some distant place.

“I’m sorry, Mrs Stanton. I know this is the last thing you wanted to hear. I mean, we knew the risks with AML. But, I guess one never is fully prepared for a relapse. Of course, we’ll do everything to fight back – we’ll use a new combination of drugs. And there’s the clinical trial for that new chemo regimen I spoke to you and your husband about. The hope is for remission, so an allogeneic stem cell transplant can be performed. The outlook, as we’ve discussed before, is not the best. Whatever happens, though, you should know we’re in for the long haul.”

That’s it, then. He is sorry. It’s over? Lisa feels confused. What is he saying? She feels like a child, unable to comprehend, though she thinks she should, and decides not to ask him to explain. She feels exhausted. She wants to lie down somewhere, curl up and go to sleep.

Lisa is nearly always exhausted. She walks with a plodding gait and regularly emits weary sighs. Though she is still good-looking, thank God, when she looks at herself in the mirror, she says to her reflection, “Who will love me again?”, staring into eyes that are often bloodshot and have dark smudges beneath them. She keeps a tube of concealer in her medicine chest to cover the circles; it’s the only make-up she ever uses now. Peering some more at the face, she made other unpleasant discoveries: her cheekbones seem too exaggerated, too pronounced for her now gaunt face, as though they belonged to someone else – perfect for some anorexic runway model but for her, they’re too severe, making her look like a fierce-eyed savage. Worse was her discovery that her post-pregnancy body with its luscious, womanly curves – the full boobs, the accentuated hips – with which she’d fallen in love, and with which Steven had been enthralled, had all but disappeared. She’s actually quite skinny now – emaciated even; she’d stopped eating again, and lost weight rapidly since the baby has taken a turn for the worse. For her visit to the hospital, she has brushed her hair back severely into a neat bun, from which not one loose strand of hair can escape. She is prophylactically dressed in a high-necked, ruffled pink Victorian blouse, a knee-length dun-coloured pleated skirt whose waist is now too loose, and sensible tan pumps. She looks like a believer (which she isn’t) in a particularly strict Christian sect, or perhaps an old-fashioned woman dressed for work at some government office. But Lisa no longer works; she quit her job after the baby’s sickness reappeared.

She stands looking at the child almost serenely, and brushes her hand against the baby’s feeble arm and offers it a small, placating smile before turning away from what she sees as a look of simultaneous hope and dismay clouding its eyes.

It’s a setback, of course, the doctor continues, staring at the baby’s chart – and avoiding looking at her, Lisa realises. Her mind wanders listlessly. His words sound almost like an admission – though of what, she is uncertain. It can’t be of guilt. She’s the guilty one, she’s the one responsible for passing on this sickness from her womb.

The doctor is a slightly built, light-skinned man with a slight stoop, sloping shoulders and a smattering of freckles across his nose and cheeks. Lisa thinks it is funny for a black person, regardless of lightness of hue, to have freckles. Staring at his thinning widow’s peak, she has a sudden urge to giggle. We’re all going to die, she thinks, and the thought makes her queasy. Beads of sweat erupt on her forehead.

A fat nurse waddles by in her too-tight uniform, her pudgy, white-stockinged legs rubbing together noisily with a hissing sound. Lisa wonders if she plans to start a fire. Overweight, Lisa mentally corrects herself, that’s the politically correct term. The nurse gives Lisa a tight, sympathetic smile, her chins wobbling, and Lisa, who is unable to look away from her, feels somehow exposed, diminished by this fat woman who perhaps has perfect – normal – children of her own.

To take her mind off these spiteful feelings brewing within her, Lisa focuses her attention on the doctor. He is reputedly one of the best paediatric oncologists in the Caribbean. She looks at his nameplate through a sudden blur of tears. Dr J Paul Mountbatten. Mountbatten. A regal name. Isn’t the Queen a descendant of some Mountbattens or other? And what about his Christian name? Is the J for John? No, it wasn’t something that common. She’d heard a doctor colleague of his, a well-preserved woman, maybe in her late-forties, greet him by his first name. Something Spanish? What was it? I ought to know my child’s doctor’s first name, she thinks angrily.

The doctor is still flipping through the baby’s charts, as if for the answer to some unknown question. Lisa feels offended by this action. The tears that had been gathering in her eyes and in the back of her throat a moment ago have evaporated. Look at me! she wants to scream at him. Why are you telling me this?

In a corner of the ward, which is painted a soothing, neutral light yellow, a bald baby begins to wail. There is a movement towards the cot by the overweight nurse. Lisa looks at her with contempt.

Lisa’s knees feel like rubber. She turns back to face the doctor and is struck by a wave of nausea. Hug me, she thinks wildly. Squeeze the loneliness out of me. She imagines herself collapsing helplessly in a sobbing ball at his feet. She would indeed launch herself at his feet, if that would help, if that would save her child’s life.

His beeper goes off. He retrieves it from his waist and frowningly examines it before replacing it. He does not excuse himself, which is a relief for Lisa, who just now feels the need to be near him. As she watches him go over the chart she wants to throw herself at him, peel off his skin and burrow inside. But she will not embarrass herself; she will not embarrass him. Her own embarrassment is secondary, unimportant. She knows about other people’s embarrassment; it is something she has become intimately acquainted with during the past few years. She is accustomed to the nervous titters of preschoolers, the shifty looks in their parents’ eyes when they are out in public, in the waiting room at the doctor’s, for example, when the baby is seized with nausea and starts projectile vomiting. “It’s the chemo,” Lisa would explain, compelled to apologise in her forgive-me-for-all-this tone of voice, the voice she had often used on her husband before he left. The parents would huddle their children close to them, nod uncomfortably, avoiding eye contact. As if they, too, thought it was all her fault that her child was sick and dying.

Outside the hospital it’s a gloriously brilliant March day that makes the eyes hurt. After eleven successive days of rain the sky is clear and blue; everything is lush and green, cruelly alive; as if the greyness and death inside the building does not exist. Lisa breathes in deeply, looking up at the sun. Nobody tells you how hard it is being a single parent of a sick child. She even wishes that she had been raised with some faith so that she could pray. It feels like there’s a conspiracy of silence about the difficulty, even among other parents of chronically and terminally-ill children. It was how it was with women who’d had children and were reluctant to tell the truth about the real pain of childbirth or that pregnancy often made a woman horny, endlessly dreaming of penises, penises and more penises.

She tries to throw up in a corner of the recently mown front lawn and when she is unable to do so, goes to sit on a concrete bench beneath an ancient lignum vitae tree; under it, mounds of raked leaves mixed in with mown grass and general trash and debris stand waiting to be bagged and tossed out. She stares at a bug marching up the side of the tree trunk, the dappled mid-morning sun’s rays warm against her face. There are many benches like this one, scattered across the grounds. To help family members compose their thoughts about what faces their loved ones, she imagines. She notices a man and woman seated on a nearby bench beneath another tree. The man has his hand around the slender slumped shoulders of the woman who is staring blankly into space.

Lisa averts her eyes. She can hear the muffled sound of traffic in the distance, the world going on without a care for her problems. She thinks about her mother, who died in the first year she and Steven were married. Thinking about this is not a good idea. Never has she felt so much like an orphan. She has never been in touch with her father, who’d never taken an active role in her life. A divinity student from a prominent Westmoreland family, he’d had an affair with Lisa’s mother for almost two years, then dumped her when Lisa was born. Her mother was the secretary at the Bible College where he’d been studying. His family’s lawyers had discreetly arranged for a generous maintenance package for the child, with the stipulation that there would be no public identification of their bastard grandchild’s father. Who was there to tell? Lisa’s mother had no other living relatives. She found another secretarial job after she had the baby, and devoted herself to Lisa’s welfare and happiness, raising her less like a daughter than a sister. They’d even double-dated a few times in Lisa’s teenage years. Lisa’s friends had all been amazed at the openness of their relationship, how they spoke honestly about sex, for instance. Because of her own bad experience, Lisa’s mother urged her daughter to give her virginity only to a man who was worthy of her. Lisa had waited until she’d finished high school to engage in her first sexual encounter, though the man had undoubtedly not been worthy – his name had long escaped her – simply a man who’d offered her lift one rainy day as she stood waiting at a bus stop. Lisa, at eighteen, felt as though she hadn’t completely disappointed her mother because she’d waited, and that had to count for something.

Now, Lisa feels the familiar dull ache in her breasts. She remembers how sharp the pain had been, the burning pain in both nipples, when she’d been nursing. How that electric suck of the baby’s lips on the swollen tips, the lightning rod sensation zigzagging straight to her womb and oh, the delicious but illicit thrill of the pain, had made her feel more of a woman than at any other time in her life. How desperately she wishes she could still speak to her mother – the former festival queen who drew swarms of men buzzing like bees around flowers. She had been so young looking, and in seemingly good health, when a stroke felled her one morning and she’d died a week later. In retrospect, Lisa remembered the lingering flu that had developed into a bronchial infection. Lisa had been crippled by a sense of abandonment that whole first year of her marriage, leaning heavily on Steven for emotional support. For two weeks after the funeral she had stayed home in bed, too depressed to face the world, beseeching Steven to take time off work to stay at home with her. She had imagined her mother being around to enjoy the arrival of the grandchildren she’d anxiously anticipated from the day she’d walked Lisa down the aisle.

What comes after? Lisa asks herself now. “Let go, and let God,” is the reply inside her head, which is really nothing but the echo of a non-sequitur she’d heard her father using to his well-heeled congregation, several times during one of his sermons. Lisa had kept close tabs on him and knew when he’d moved to Kingston to take up an appointment there. He’d become a respected and charismatic figure within ecumenical circles. Despite her bitterness at his treatment of her, she would sometimes creep into the back of the church to watch him. She was always struck by his handsomeness, his articulateness. He’d gone grey at the temples and some of his muscle tone had begun to go soft, but she could still divine the lover in him. She could understand how her mother had been seduced by him, by his silver tongue that she imagined had called on the name of Jesus even as he’d thrust, swollen and insistent, into her mother’s yielding flesh. The truth was, as she glanced round at the adoring faces of his female congregants, who hung on to his every word, throwing their amens and hallelujahs wantonly at him as though they were undergarments, she was secretly a little proud of him. That day, as the organ swelled mournfully in the background, Lisa had watched him in his sober suit and formal tie, his secret life locked within his breast. “When nothing’s left,” he had intoned – a flash of a bracelet appearing from beneath his cuff when he held up a forefinger in admonition – “Friends, God is there.”

But he isn’t really, she thinks now. Faith was what people leaned on to get them through difficult times, but she can’t bring herself to start believing in a god she despises, one of whose representatives was a hypocrite like her father. Still, where did it leave her as far as her understanding of the end of life? It’s an issue she’s been thinking about more and more. You go through all that shit, that pain and suffering in life and then, at the end, what is there? More pain and suffering? There was no guarantee of heaven, especially for someone who did not believe there was such a place. But, if not heaven, what?

She closes her eyes and tries to summon the presence of this god of whom her father spoke. But she can’t. That god doesn’t exist. The baby will return to the dust, that’s all. So will she, when it’s her turn to go. Nothing comes after. All that she can believe in is what’s real, what came before, what is here and now. But wallowing in the morbid does no good, so she forces herself to think about other matters. Eyes still closed, she tries to reconstruct images of what her life had been before the baby. She’d been reasonably happy despite the less-than-perfect circumstances of her childhood. She’d grown up and had friends and she’d even known love. When she’d gotten pregnant, she’d felt her life was complete, especially because she’d believed that having children would be impossible. The baby. What joy she’d felt on her safe arrival. This perfect creature. Ten fingers, ten toes. All functioning parts. She was in love, again. There had been no thought, in those early days and nights when she cradled her to her bosom and gazed lovingly into her eyes, that she was one of those defective models that ought to be returned to the manufacturer. It hadn’t occurred to her that there could be a problem.

Then, as the days turned into weeks, irritability, melancholy and restlessness had crept in. She felt guilty, as though she’d fallen out of love with the baby. Postpartum depression, the doctor had diagnosed. She didn’t exactly ignore the baby, but she was no longer as fascinated with her every move. It was during this time that she also began to sense that things with Steven had hit some kind of snag. Her doctor encouraged her to return to work, and she did. Now, she cannot really remember what her days were like when she had a computer on her desk and wore daring high heels with professional cotton-blend suits that her boss and coworkers admired.

She will have to dismantle the baby’s room, the room she’d spent so much time preparing. The furniture will have to be put in storage. Then there are all the cute little clothes to sort: she’ll give some to Joan from the office, who recently had a baby; the others she’ll give to goodwill –

Horrified, she realises that she’s already begun to think about the baby as dead; she forces herself to stop.

She pulls out her cellphone and dials her husband. He left her and their child because he couldn’t “stand the smell of sickness” and the way it made her so “damn needy”.

“Yes, Lisa,” Steven answers wearily, on the fourth ring, just before voice-mail chips in.

“Steven,” she says without preamble. She pictures him, slight and effete, fragile as a baby bird. Neat, well-groomed. Dressed in a pin-striped suit, the jacket close-fitting, double-buttoned. People called his look metrosexual, he’d once told her, and she’d had to stifle the snigger that wanted to burst from her throat. “It’s back.” She thinks of their days at Lamaze classes, and pictures Steven holding her hand in the delivery room. They were once best friends. When had they become enemies? She listens to him breathing noisily through his mouth on the other end of the line. Adenoids.

“What? What’s back?

“It’s the baby,” Lisa explains. “It’s back.”

There is silence. Then: “Jesus Christ.” He expels a long frustrated sigh, and she can imagine him rubbing the elegant high bridge of his nose. “Where are you? Well, look, I’m in the middle of something here,” he says. “I have to call you back. This evening, OK?”

She hangs up before he does, knowing what he’s thinking. He’s thinking she is using the baby’s sickness as leverage to get him to come back home. There is a hurricane of emotions swirling around inside her, feelings she is unable to express. She doesn’t want him back, and yet she does; she can’t go through this alone. Mostly, though, she’s confused; the idea that he would ever have left had never occurred to her.

She gets up and wanders back towards the building, but at the sliding glass door, changes her mind. The thought of going back inside there with the sickening hospital smell of antiseptic makes her want to retch again, and so urgent does the need to pee become, that she hurries around the side of the building instead.

The hospital’s grounds are huge. She remembers seeing them first on a brochure someone from her workplace had handed her. She remembers thinking that surely the baby would be cured at such an impressive structure as this. The hospital itself is a magnificent ivory-coloured edifice with sloping green-shingled roofs. It had been built in the economic boom of the mid-1980s, by the government with assistance from the Jewish businessmen’s league. Lisa’s footfalls are soundless in the high grass around the side of the building.

Lisa vomits, then squats to pee when she finds a suitable spot, near a pile of leaves under a tree. A sound somewhere makes her pause, mid-flow, a Kegel contraction that makes her pubis throb with pleasure. She looks up and sees that she is being observed by the grounds-keeper, a stocky deaf-mute she’s seen around the institution. He also works as a cleaner on the wards; Lisa remembers seeing him with his mops and other accoutrements. They had on occasion exchanged looks; there was one time Lisa noticed something in his eyes. Steven had noticed it too. They had been on the ward one night, when he’d come up the hall, noisily dragging his roller bucket with the squeaky wheels, dirty water sloshing out over the sides. The baby had just been diagnosed; they’d been keeping vigil beside her cot.