Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

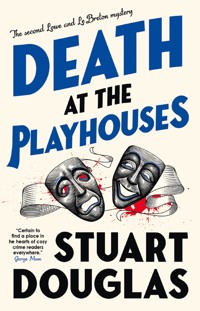

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

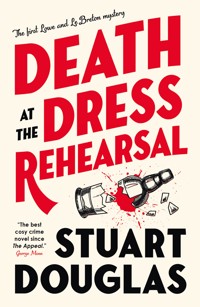

'Douglas brings a light touch to an intriguing mystery centred on two opposites… Together they give a flying start to a new crime series' The Daily Mail Two ageing actors attempt to solve a murder after a body is found on the set in this witty, fun whodunnit, perfect for fans of Thursday Murder Club and Death & Croissants. In 1970, while on a location shoot in Shropshire for the downmarket BBC sitcom Floggit and Leggit, ageing actor Edward Lowe – a 'short, stocky northerner with a receding hairline and bad eyesight', who plays the pompous and officious lead, a role based on himself – stumbles across the body of a young woman, apparently the victim of a tragic drowning accident. But there's something about her death that rings the faintest of bells in his head and, convinced the woman has been murdered, he enlists the help of his laid-back, upper-class co-star John Le Breton, a man for whom raising a wry eyebrow is a bit too much of an effort, to investigate further. Crossing the country and back again during gaps in filming, the two elderly thespians make use of their wildly contrasting personalities and skillsets to uncover both a series of murders in the modern day and links to another unfortunate death during World War II. But, as the body count mounts and a pattern to the killings begins to emerge, can Edward and John put their differences aside to save the innocent victims of a serial killer and still be ready for when the cameras start rolling? Death at the Dress Rehearsal is the first in The Lowe and Le Breton Mysteries series.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Praise for… Death at the Dress Rehearsal

Also by Stuart Douglas and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise for…

DEATH AT THEDRESS REHEARSAL

The first Lowe and Le Breton mystery

“Death at the Dress Rehearsal is certain to find a place in the hearts of cosy crime readers everywhere, with its breezy prose, its witty observations and the often hilarious interplay between its two thespian leads – not to mention the cracking mystery at its heart. Stuart Douglas has just delivered the best cosy crime novel since The Appeal.”

George Mann, author of the Newbury & Hobbes series

“It was a joy to be in the company of these Dad’s Army detectives. I read the whole book in one sitting. Hugely enjoyable and lots of fun.”

Nev Fountain, author of The Fan Who Knew Too Much

“Glorious and ingenious. What a lovely start to what I hope will be a long-running series!”

Paul Magrs, author of Exchange

“Death at the Dress Rehearsal is a real tootsy-pop of a mystery thriller, with an irresistible conceit and enough twists and turns to bamboozle the most conscientious of armchair sleuths. Think you won’t love it? Who do you think you are kidding…?”

Steve Cole, author of the Young Bond series

“Holmes and Watson by way of Arthur Lowe and John Le Mesurier; a wonderfully mismatched duo who you can’t help falling in love with.”

Trans-Scribe

Also by Stuart Douglas and available from Titan Books

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Albino’s Treasure

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Counterfeit Detective

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Improbable Prisoner

“Death of a Mudlark” in Sherlock Holmes: The Sign of Seven

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Crusader’s Curse

DEATH AT THEDRESS REHEARSAL

The first Lowe and Le Breton mystery

STUART DOUGLAS

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Death at the Dress Rehearsal: the first Lowe and Le Breton mystery

Print edition ISBN: 9781803368207

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803368214

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: June 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Stuart Douglas 2024. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Julie, Scott and Paul.

And for my Uncle Eddie, who Ipromised I’d put in my next book.

PROLOGUE

The taste of blood in her mouth reminded her of childhood; a fall from a swing and a sharp blow to her chin which had rattled her infant teeth. Then, her father had caught her up in his arms and carried her away, cleaned her up and given her ice cream and orange juice. But there would no such rescue this time.

Instead, she stumbled through the thick gorse, alone and aware of the closeness of her attacker, only a few yards behind her. She could hear breathing at her heels and a soft voice calling her name. “Give up, Alice, there’s nowhere to go.”

Whether that was true or not, she didn’t know. She could only hope she would come to a road, and that a car would pass and miraculously she would be saved.

When she had fled from the car park, away into the darkness, she had been heading uphill, and now she crested a small peak and, to her delight, made out a faint glow a hundred yards or so ahead. She risked a glance back, but the blackness of the countryside was so complete that she could see nothing, only hear the steady tread of someone close behind her, in no hurry to catch up. The certainty in that tread, the conviction that her capture was inevitable, was almost enough to break her, but instead she forced herself to increase speed, tripping and half falling as she pressed onwards, wondering if she might somehow fashion a weapon from something lying about. Anything to gain enough time to reach the lights.

But she knew the moors from her father’s descriptions, and knew the ground was scrubby gorse for miles around. There was barely a tree that might have shed a handy branch, and if there were any heavy rocks to hand… well, unless she tripped over them, they would go unseen. And she could feel her strength fading, her lungs tightening as terror-filled panic and unexpected exertion combined to rob her of breath. Perhaps it had been a mistake to try to go faster? Perhaps she should turn and fight? No, better to get to the lights and, if necessary, make her stand there.

Fifty yards, forty, thirty…

She almost fell as she left the rough ground and stepped onto the narrow, dimly lit path. Viewed up close, she could see these were not the streetlights she had hoped for. She felt her stomach sink as she realised they were simply small electric handlights, strung in haphazard fashion along a fence that skirted the far side of the path. She stopped and stared stupidly at the topmost metal cord of the fence, one of three lines of thin steel wire which stretched between wooden stanchions off into the darkness in either direction. A cold wind blew in her face. She realised the sounds of pursuit had ceased, and knew, as a cornered animal does, her pursuer was directly behind her.

She clenched her fists and tensed the muscles in her arms and legs, ready to spin around and launch herself at the figure to her rear. She pressed the balls of her feet down onto the gravel and prepared to turn…

The blow, when it arrived out of the blackness, was hard and heavy. It connected with the side of her head so swiftly that, for a moment, she wasn’t even aware she’d been hit. Her body continued to move, twisting around to attack even as the strength in her arms suddenly disappeared, while her head was forced in the opposite direction by the force of the blow. She felt muscles tear in her neck before she felt the huge, dull pain in her head, and then her legs went from under her and she staggered to the left, and collapsed on wet grass. Her eyes were open but she was incapable of focusing them, so she felt rather than saw her attacker grab her beneath the arms and haul her along the ground, then heave her to her feet and prop her against something hard but yielding, which dug into her side and shoulder. She opened her mouth to speak, to ask why this was happening, but no words came out, only blood and a few indistinct, wet sounds. She felt something press against her lips and smelled spirits, and then something slap against her chest, and she willed her hands to come up and grab whatever it was, but try as she might, they remained uselessly limp at her side.

There was surprisingly little pain, she realised.

The pressure on her chest eased, then ceased altogether and, for a second, everything was silent and still. She sagged backwards gratefully, and sucked cold air into her lungs… then, as though from a great distance away, she heard someone say her name – Alice – and felt hands grasp her ankles. Her head fell backwards as her legs were lifted into the air until a tipping point was reached, and suddenly there was nothing to support her.

Without a sound, she tumbled into space. She had time to trace a half turn in the air, then she struck water colder than any she had ever known before and was engulfed in its freezing embrace.

1

Edward Lowe let the witless tittle-tattle wash over him and tried to pay it no attention. It was the same every morning. He would arrive with a copy of The Times, take a seat beside John Le Breton, and pointedly and noisily open it. The implication was obvious, surely? That he had no desire for conversation and would appreciate a little silence in which to read the news, first thing in the morning.

And yet, without fail, he would get no further than the first paragraph of the first column before John and whichever girl was doing his make-up would start. Such-and-such was seeing so-and-so, whatshisname was putting on weight, and you-know-who was rumoured to be about to be shifted to a new show on account of his dislike of one of the new producers. It was the banality which grated most – that, and the way in which his girl would invariably get involved. Within two minutes, she would stop mid-application and, in a tone he felt was better suited to Norman Evans gossiping over the garden wall, say, “Well, what do you think of that, Mr. Lowe?”

It really was too much.

“Do you think we could have a little quiet for once!” he snapped, then immediately regretted it.

Everyone was looking at him. It would have been preferable if they’d snapped back, but the closest any of them got was John’s raised eyebrow, and even that was accompanied by that infuriating half smile of his. The girls just giggled. They were used to his occasional outbursts, he supposed. He’d heard one of them say, “you have to make allowances for them, they’re that old” once, and the memory rankled afresh.

“I think we’re done now, in any case,” he grumbled, and pushed himself to his feet, pulling the tissue from his collar and dropping it on the floor. He’d had enough for one morning. He needed some air.

Without another word, he tramped down the stairs of the make-up van and left them to their gossip. There was a bitter wind blowing from the reservoir and it was still an hour before he was needed for shooting, but it would be better to wander across the freezing moorland than stay inside in an awkward atmosphere. He buttoned his coat up, buried his chin in its collar, and set off along the path around the water, away from everybody.

* * *

The worst of it was, he knew he was at fault. His mood had been foul since the previous day, when the show’s producer, David Birt, had leaned over the top of the chair in which Edward was almost napping and informed him that the following day’s shooting had been changed.

“Apparently, there’s a problem with the swimming pool we were intending to use, so we’re going to do the scene at a reservoir up the road instead,” he’d explained, with a tiny shrug. Then he’d handed over a thick sheaf of paper. “I know this isn’t going to make you happy, Edward, and believe me, I’d prefer not to be doing it, but there are new lines to be learned, I’m afraid.”

Even if the last-minute change hadn’t been enough to sour his mood, that little dig about new lines would have riled him. He knew it annoyed the others, his refusal to allow work to intrude on his private life. But he was damned if he was going to waste his evenings – which should be spent in front of the fire, with a glass of something decent and good music playing on the stereo – muttering lines to himself, with the script face-down in his hand, like some grubby schoolchild cramming for an examination. Even here, on location for Floggit and Leggit (and what a ridiculous title that was!), he refused to spend his evenings committing tripe to heart as though it were Shakespeare. Close enough was good enough for this kind of thing.

“It’s really not on, David,” he’d remonstrated, knowing it was a futile exercise, but unwilling to let the change pass without protest. “This is the second time in this run, you know? What was the excuse last time? The costumes weren’t ready, wasn’t it?”

“The costume girl’s mother died, Edward.”

“I know that, David! Though you’d never know we employed anyone to look after that side of things, given the shoddy state of some of the props. The antique miniature I was supposed to be appraising last week was a photograph of Guernsey in a plastic frame! As for the costumes…”

His voice had trailed off into ill-tempered silence and he’d taken refuge in lighting a cigarette, conscious that to say anything else on the subject would be to place himself in an invidious light.

“Well, if you could look over the new pages, Edward…” Birt had motioned towards the papers which Edward had already dumped on the table. “Of course, nobody expects you to be word-perfect tomorrow!”

He’d smiled, but Edward had been having none of it. He’d made as non-committal a sound as he could manage and nodded once, almost imperceptibly. Birt had stood for a second, then, evidently deciding no more need be said, smiled again and headed for the bar, leaving Edward to stare at the script with a baleful eye.

Learning lines had been easier when he was younger, of course. When he was doing rep, he’d only needed to look at a script once for it to become lodged in his head forever. He could still quote chunks of any number of long-forgotten plays, whole convoluted speeches which nobody else remembered, or would ever speak again.

Irritated, he peered at the top page of the new script. With a sigh, he skimmed through the episode synopsis.

THAT SINKING FEELING. Wetherby convinces Archie and the shopkeepers to test out a collection of vintage divinggear at the local reservoir. High jinks ensue when Wetherby ends up adrift in a rubber dinghy and Archie attempts to rescue him in a moth-eaten diving suit.

About par for the course, really. Last week it had been Joe Riley, who played local councillor Brian Clancy, and Donald Roberts, as the incontinent Vicar, trapped in a pub cellar with no access to a lavatory. He’d almost called his agent when he’d seen the episode was called “Bottoms Up”. High jinks, indeed. It was just another word for unnecessarily coarse behaviour, in his opinion.

He hadn’t called, of course. He knew exactly what his agent would have said. That Floggit and Leggit was his biggest break in years and that, after a professional lifetime spent as a supporting actor, this was his chance to play the lead on television.

The question he had to ask himself – that he had asked himself every day since he’d signed the contract – was whether being the star of a cheap-as-chips BBC series in which the elderly shop owners of Groat Street Market got into allegedly hilarious scrapes was really the height of his professional ambitions.

He’d really thought that by this stage in his career he might be doing better than playing George Wetherby, the self-important owner of a provincial antique shop in a slightly vulgar situation comedy. If 1972 was anything to go by, this was going to be a tedious decade, professionally speaking.

And it wasn’t as though he didn’t learn his lines, was it? Most of them, anyway. Birt and Bobby McMahon, the writer, could hardly expect perfection straight off the bat, not when he was only given one evening to learn page after page of arrant rubbish. Because the quality didn’t help. Of course, it didn’t. Give me Hamlet or Lear, Edward thought with a burst of fresh irritation, and it would stick like glue. But “hand me that chamber pot, Archie,” and “where have your trousers gone, Malcolm?” Not exactly the Bard, was it?

Perhaps he should just retire and accept his glory days (such as they’d been!) were behind him. He wasn’t the only one, either. Joe Riley might bleat on about working with Hitchcock and his days at the Old Vic, but there was a reason he was reduced to playing a sour-tempered local-government man. And as for Donald Roberts…

He shook his head and smiled to himself, bad temper all but forgotten as he recalled old Donald remarking mildly that, after a lifetime in the business, all he’d be remembered for after this was Malcolm the Vicar’s allegedly hilariously weak bladder and propensity for misplacing his trousers.

At least Wetherby was only the guiding force of the Groat Street pensioners, and not quite one himself.

The thought that, even in his sixties, he was still one of the younger cast members served to dissipate the last vestiges of ill-humour from Edward’s mind, and he finally looked up from the ground to discover where his angry steps had taken him – just in time to stand in something soft and wet. He jumped to one side automatically, but the damage was done. He lifted the offending boot and peered myopically down at it.

Well, that was a relief. No sign of dog’s mess, at least.

He glared at the path and discovered the source of his momentary confusion. A grubby rag had been flattened against the gravel by the pressure of his boot, squeezing a pale, watery liquid into a puddle around it. A little of the liquid had darkened the bottom of his boot, but running the sole across some of the ever-present gorse quickly removed all trace of that.

For the first time since he’d stomped out of the makeup tent, Edward spent a moment taking in his immediate surroundings. His foul mood had evidently caused him to quicken his pace, he realised, for the set was sufficiently far away that he could make out only lorries and a tent, with the figures hurrying around them as indistinct and blurred as if he’d removed his spectacles. Otherwise, there was little to see. Ahead, the path disappeared around a bend and to the right the gorse extended across a field until it too vanished at the horizon.

Which left only the reservoir itself, ringed to his left by a low fence and, here and there, isolated stunted trees which bent at unnatural angles where the wind had buffeted them throughout their existence. No matter where he looked, there was nothing interesting to see. Not that it mattered. He should really be getting back to the set, in any case.

He turned on his heel, bored now of both his bad mood and the cold wind, and, in doing so, inadvertently caught the rag with the toe of his boot. It unfolded with a wet slapping sound, and lay flat on the grey pebbles, a sodden white square, unexpectedly edged with intricate lace and exuding a familiar odour.

Brandy.

Curious, Edward knelt down to examine it more closely, but immediately froze in shock. Crouching low, he could now see underneath the nearest bush. And there he could clearly make out two fists clenched tight upon clumps of grass and, between them, the pale face of a young woman, whose blank, staring eyes and slack mouth left no doubt she was dead.

For all that he’d spent much of the time working in radar and had never seen action, he had been posted out East during the last war, and he’d seen his fair share of dead bodies. So perhaps it was the juxtaposition of English countryside and wide-eyed corpse that caused him to shiver with shock. For several long seconds he stayed painfully crunched on his haunches, until, with a start, he scrambled backwards, falling hard onto the path, scratching his hands on the gravel. His eyes never left those of the dead woman.

There were white ice crystals in her long eyelashes and in her dark hair, and, as he crawled slowly towards her, he could see her lips were a pale blue. There was something familiar about those eyes, though, something hovering on the tip of his tongue. But even as he thought about it, it was gone, and he was tearing his gaze away. Over her shoulder, he could see the inadequate fence directly behind her was damaged. Had she fallen in the reservoir, perhaps, and dragged herself out, only to succumb here, frozen and without the strength to go any further?

He levered himself to his feet and, touching nothing, leaned forward to get a better look. The fencing around the water consisted of wooden poles, probably rotten, spaced out every dozen yards or so, with thin metal wire strung through each pole at three points, equally spread up the wood. The top wire behind the dead woman had been pulled back towards the reservoir, causing the poles on either side to lean in towards one another at a steep angle.

She’d gripped onto the metal and pulled herself out of the water that way, he realised, with a muted approval. Never give up was a mantra he’d always embraced, ever since he’d returned from the War, a short, stocky northerner with a receding hairline and bad eyesight, and decided he wanted to be an actor. He had never quit on anything, and it seemed this poor woman had been the same, at least while her strength lasted.

He was looking around for something he might use to cover her up and restore a little of her dignity when he became aware of a figure running towards him from the direction of the set.

“You’re wanted, Mr. Lowe,” the young man (Edward had no idea what his name was, but he’d seen him around) shouted as soon as he was within earshot. When Edward made no move towards him, or even acknowledged his existence, he repeated the shout, then, when the distance between them was sufficiently small that shouting would be both unnecessary and rude, said in a quieter voice, “David says could you come back, please, Mr. Lowe? You’re wanted on set. Dress rehearsal is about to start and David’s worried you’re not in costume yet.”

Edward looked at him blankly, the words making no sense – or rather, communicating nothing of importance. He pointed downwards, underneath the bush. “I think you’d best go back and tell David there’ll be no filming today,” he said, finally.

2

The rest of the morning was spent in a series of meetings and interviews, in which Edward was forced to repeat the same brief tale over and over again to a variety of official – and unofficial, but just as interested – parties.

“I have already explained all of this to your colleague,” he found himself saying to a police inspector who had been called in from the city. Constable Primrose, the bobby in the local village of Ironbridge, had been deemed too inexperienced to investigate a sudden death on his own.

The inspector nodded. “I’m aware of that, sir,” he said, “but in cases like this, I prefer to hear any recollection first-hand.”

Edward bit off a sigh. The man was only doing his job after all, and, even if it was annoying to constantly repeat oneself, he supposed he should be pleased the police were being so thorough. For the umpteenth time, he cast his mind back to that morning.

He had remained by the body while the young assistant had run back to tell everyone what had happened, and to phone the authorities. Within a few minutes, David Birt, Bobby McMahon and one or two of the cast had arrived. The youngest of the actors, Jimmy Rae (who played Wetherby’s idle son, and had hair as long as a girl’s), had brought a blanket, which he and John Le Breton had draped over the dead woman.

That had been the first time he’d had to tell his story, such as it was; how he’d walked for a bit and kicked the white handkerchief…

The handkerchief. He’d forgotten all about that.

“As I told your colleague, I’d forgotten all about the hankie until then, you see,” he said to the inspector. “It was only when I was telling everyone about finding the body that I remembered why I’d bent down in the first place.”

It had been in the exact same position. Through sheer good luck, nobody had disturbed it as they came running up, every man somehow contriving to step over or around it. He’d stooped low and poked the sodden fabric with a pencil. A fresh trickle of what he was now sure was brandy oozed from it.

“That’s what made me check it, you see,” he said. “That and the fact I could see the lace trim. It seemed an odd thing to be lying on the path, out there in the middle of nowhere.”

“Could be a clue,” Jimmy Rae had said.

“A clue to what exactly?” Edward had asked, testily. Jimmy seemed a nice enough boy and had been fine so far playing the series’ youthful heartthrob, but he was inclined to the melodramatic. He had a background in experimental theatre, apparently. All foul language and insufficient underwear, he shouldn’t wonder. “Clearly, the poor woman fell in the water last night and, though she managed to pull herself out, she hadn’t the energy to get any further.”

“So, what’s with the hankie, then?” Rae had pressed. “How did it get over there, and why’s it soaked in drink? I reckon there’s been foul play here.”

Edward had heard the relish with which he’d said foul play, like a detective in a Bulldog Drummond movie. Before he could say anything, though, John had interrupted, in his usual mild, slightly distracted tone. “It could be purely coincidental, I’d have thought.” He smiled and waved one hand in Edward’s direction. “Just because it prompted Edward to… hmmm… squat down, doesn’t mean it has anything to do with this poor lady’s fate.”

“John plays Archie Russell, who works in my antique shop on the show,” Edward explained to the inspector. “He’s had a reasonable career, of course – made some films and spent time in America, I believe – but he can be a bit vague at times. He has a tendency to fall back on an ‘oh my, I don’t know how to tie my shoelaces, won’t someone find Nanny to do it for me’ little boy routine at the drop of a hat. But there was no denying the sense in what he’d said, so we decided the best thing to do was to leave the handkerchief where it was, until your lot arrived.”

“Quite right too, sir,” the inspector nodded. “So, you moved nothing until Constable Primrose arrived? Which would be approximately twenty minutes later?”

“About that, yes. We did wonder if perhaps we should head back to the village, but it seemed disrespectful to the dead woman to leave, and I knew someone would want to speak to me.”

“You did the right thing,” the inspector said.

It had been bitterly cold. The chill wind had grown stronger and a dirty drizzle had set in, not too heavy, but incessant. There was nowhere to shelter, but Edward had been certain the police would arrive very soon, and so had insisted on staying put. Later, he’d wondered why he hadn’t gone back to the set at least, and sheltered in the food tent, but the thought hadn’t occurred at the time, and because he was staying, the others did too. David Birt had left instructions that one of the crew was to guide the police to the body when they arrived.

“But no, nobody moved anything before the constable turned up. He was the first person to touch the body. He was the one who found the paint, in fact.”

Constable Primrose was a skinny beanpole of a man, in his early twenties, at a guess, with already thinning fair hair and a wispy moustache. He was ridiculously young to be the only policeman for miles around, in Edward’s opinion, but still, for reasons he’d never been able to explain, he had taken an immediate liking to the boy and was careful to portray him in as favourable a light as possible to his superior.

“He took in the scene very commendably, you know,” said Edward, leaning forward slightly and tapping on the inspector’s notebook, as though reminding him to write it down. “He had us all move well back, then he checked the poor woman over thoroughly and realised there was something on her blouse.”

In reality, the tall constable had stood indecisively for some time, rubbing his fingers on his chin and glancing repeatedly from the body to the group of actors. It was only when John had murmured, “perhaps you should, you know…” and indicated the corpse, that he had nervously knelt down.

“Ooh, she smells of drink something terrible,” Primrose had said, as he turned the woman over onto her back. “And there’s something on her top,” he’d gone on, then yelped in alarm. “It’s coming off on my hands!”

He jumped up and showed them his palms. They were covered in small white flakes, like dandruff. Primrose had rubbed his hands on his official police black trousers, leaving faint smears down each thigh.

As if released from a trance by his actions, the others had surged forward as one and crowded around the body. Viewed from the comfortable position of the hotel bar, with the inspector seated across from him and a glass of passable Merlot in hand, Edward thought that perhaps he had not been quite so quick as the others to gape mawkishly at the poor woman. John Le Breton, however, had been very much to the fore.

“I do believe it’s paint.” Edward had never previously heard John express any emotion stronger than wry amusement, but there was a definite note of interest in his voice as he pointed at the policeman’s leg. “Look, there’s a patch of it on the front of the poor woman’s top.”

The inspector coughed and shook his head slightly. “Actually, it turns out it’s not paint. We think it’s some kind of face powder, probably from a compact she had in her pocket. It must have partially dissolved in the water and soaked through the dead lady’s clothing.” He smiled, but there was no warmth in it. “It’s a bit of a lucky break, actually. The fact it only partially dissolved shows she wasn’t in the water long.”

“I thought that must be the case,” Edward agreed. “I said as much at the time, when we took a closer look.”

Primrose had at least closed her eyes, Edward was pleased to see. He’d pushed his way past David Birt and peered down at the girl. She was brunette, around thirty, he would guess, fashionably dressed in a bulky jacket and blue slacks. A pale cream shirt was visible beneath the jacket, the pocket stained. The knees of her trousers were filthy. Her shoes, he noticed absently, were missing, presumably lost at the bottom of the reservoir. Her bare toes pointed back towards the water.

“Rather a pretty girl,” John had murmured softly at his side.

Edward had whipped his head around, a reminder on his tongue that there was such a thing as decorum, but the look on the other man’s face was so maudlin that he bit off the remonstration, and left it unsaid.

“Yes,” he’d said instead. “She was. She can’t have been in the water long, or… youknow…”

He let his voice trail off as an image skittered across the edges of his mind. There was something wrong about this… something not as it should be…

Whatever it was, it remained frustratingly out of reach. The instant he’d tried to concentrate on the wispy half-thought, it was gone, and he was left still staring at John.

“And then PC Primrose covered her with his coat, and asked us all to go with him, back to the filming area,” Edward concluded, suddenly keen for the inspector to be on his way. He drained his glass, troubled by that final momentary sense of familiarity. “After that, you chaps took over,” he said. “That’s all I can tell you, I’m afraid.”

“You’ve been very helpful, Mr. Lowe,” the inspector said. He scribbled a last line in his notebook and folded it shut. He glanced around quickly and lowered his voice. “Unofficially, I can tell you that we believe that the lady was out hiking and fell into the reservoir while under the influence of alcohol. The smashed remains of a half-bottle of brandy – the label was in perfect condition, so recently dropped there, and therefore we believe linked to the drink-soaked hankie you found – was discovered near her body. That’s not something to be shared at present, though,” he cautioned. “We’ve not spoken to her next of kin yet, you understand.”

“Ah, so you know who she is, then?”

“We do. Ironbridge isn’t a big place, Mr. Lowe, and PC Primrose was able to supply a list of the bed-and-breakfast establishments at which the lady might have stayed. Mrs. Alice Burke, her name is. Was. She was a guest at the second one we tried. The landlady said she arrived yesterday morning, on a hiking holiday, one small rucksack, no suitcase. Come to see the area her family comes from, apparently.” He shook his head. “She went out last night at about nine, passed the landlady on the stairs. Said she was going for a stroll. The landlady warned her to stay to the roads and reminded her the door was locked at midnight. That’s the last anyone saw of her alive.”

He leaned in closer and lowered his voice. “It’s enough of an open-and-shut case that I’ll be leaving tonight, in fact, and writing up my report back home. To be honest, in the force, we refer to my visit as a box-ticking exercise. Sadly, Mrs. Burke’s death was a tragic accident, caused by a combination of unfamiliarity with the area and strong drink.”

“Are you certain of that? It’s just…” Edward reddened. Suddenly, he was unsure how to go on. He didn’t have strong suspicions, after all. In fact, until that very moment, he hadn’t been aware he had suspicions at all. Just a nagging sense that something at the reservoir had been amiss.

The inspector was looking at him curiously, waiting for him to continue. When the silence between them had lasted a second too long, he filled it with a gentle prompt.

“Just…?”

What could he say? That her eyes had unearthed a memory – half a memory, not even that, not even a memory at all, really – and that it had made him uneasy? He shook his head, covered his embarrassment by lighting a cigarette and letting the smoke form a cloud in front of his face. “Oh, nothing. Nothing at all. Forget I said anything, Inspector.”

There was understanding, but also a degree of condescension, in the inspector’s voice when he spoke. “I know it can be traumatic, seeing death up close, especially when you’re not used to it. But sometimes accidents happen.” He smiled as he clipped his pen to the inside pocket of his sports coat. “There’s not always a bogeyman in the background, thankfully.”

He drained the last of his lemonade and carefully placed the glass back on the table. “Please do remember what I said about not discussing anything I’ve said with your colleagues. Best all round if you just forget it ever happened, and go back to making everyone laugh. Leave the policing to the police, and we’ll leave the funny business to you lot.” He stood and offered his hand in farewell. “I shouldn’t really be telling you any of this, but given the circumstances, it can’t do any harm. And well, the wife and I are looking forward to seeing the new show. She’ll be chuffed when I tell her where I’ve been today.”

Which was pleasing, of course, but experience had taught Edward it was best to say as little as possible when a member of the public mentioned work. You could never stop some of the buggers talking once they got started, and they all ended up thinking they were your best friend after two minutes of chat. “That’s very gratifying to hear…” he began, but the inspector, it seemed, was not finished speaking.

“Oh aye, a big fan of Mr. Le Breton, the wife is. Always has been.”

Edward’s smile never flickered, he was pleased to note, and his handshake could not be criticised for a lack of good fellowship. He watched the policemen walk out of the room and waved to the barman to bring over another bottle of Merlot.

3

John Le Breton couldn’t decide if he actually liked Edward Lowe or not.

He certainly didn’t dislike him. There were very few people John did dislike, really. A housemaster at Sherborne (long since in his grave, he suspected, and felt a shiver of guilt for thinking ill of the dead) and a theatre manager in… Darlington, was it? Or perhaps Doncaster. But that was about it.

Edward wasn’t a great friend, of course. John had worked with far too many actors to be great friends with them all, even if they’d been uniformly charming and the best of company. Which, whatever other sterling qualities he might have, Edward definitely was not. He was pompous and prickly, and quick to take offence (and not backwards in giving it either, John thought with a smile, remembering his reaction to one request for an autograph).

Take that morning, for instance. Of course, he’d been rattled to stumble upon a dead body. Who wouldn’t be? Even in the War, when one rather expected to do so now and again, it had been a terrible experience, but in the incongruous setting of the English countryside, a quarter of a century later? Of course he’d been rattled.

Even so, the way he’d elbowed everyone out of the way to look at the poor woman’s paint-stained blouse had been a bit off. There were definite traces of George Wetherby in Edward Lowe, in John’s opinion.

“Which is not entirely bad, to be fair,” he murmured to himself, a habit he’d picked up while staying alone in digs across the country.

Clive Briggs, who was playing the local ironmonger in the show and who he’d known for years, looked up from his paper, assuming he was being addressed. “What’s that?” he asked.

“Oh, nothing.” John smiled and drained his glass, wiggled it in the direction of his friend. “Another one, Clive?”

He didn’t wait for an answer – what else was there to do on a rainy Monday night in Ironbridge, after all? – but gathered up Clive’s empty glass and headed for the bar. Edward looked up as he passed. The policeman he’d been speaking to had just left, and John wondered what he’d said.

“Can I get you a drink, Edward?” he asked, on impulse.

“No, no thank you. I’ve just ordered this,” he said, indicating the bottle of house red on the table. “Perhaps you’d join me, though? There’s something that’s been bothering me, and I’d appreciate your opinion on the matter.”

John glanced across at Clive, but he was laughing and waving his arms in front of Jimmy Rae, evidently already deep in some hilarious anecdote or other.

“Why not?” he said and slipped into the seat opposite Edward, as the little man gestured to the barman to bring over another glass.

Once he had his drink and Edward had replenished his, he cocked an eyebrow quizzically. “So, what’s bothering you, old chum?”

He suspected it was something to do with the policeman’s visit, and was pleased when Edward bent forward and, in an undertone he could barely hear, confirmed that suspicion. “The police are treating the death as accidental, you know?”

“So I heard. The constable told Jimmy they think she was out walking and fell into the reservoir. Poor woman heaved herself out, but froze to death overnight.”

Edward nodded. “Exactly. The inspector didn’t say that in so many words, but still, it was pretty plain that was what he meant.” He frowned. “Blithering idiot. There’s obviously more to it than meets the eye.”

Now, that was unexpected. This could turn out to be far more entertaining than he’d expected. “Really?” John said in as flat a voice as he could manage. “Wasn’t that exactly what you said earlier on?”

“I did.” Edward paused, leaving John with the impression he was making his mind up about something important. Finally, he said, “But I’ve since changed my opinion. I think something untoward occurred, even if the police don’t.”

“I must say, I thought it was all rather cut and dried,” John replied.

Edward drained his glass and refilled it, scowled, began to speak, then stopped and shrugged instead.

“Lack of imagination, that’s the problem,” he grunted.

John wondered if he meant the police or himself.

“Well, what do you think happened, Edward? What do you think they’ve missed?” he asked finally. Across the bar, he could see Clive Briggs arm-wrestling the barman, and Jimmy Rae slapping a pound note down between the two men, obviously betting on the outcome.

“I can’t say precisely,” Edward replied after a moment. “There’s something nagging at me, something I can’t quite put my finger on. And I don’t have the access…”

Evidently he thought that was sufficient explanation, for he moodily sipped at his wine and said nothing more.

It would have been simplest for John to leave it at that, and rejoin Clive and Jimmy. In many ways that would have been more in character, too. And, later, he could not have explained exactly why he didn’t. Instead, he tutted and shook his head.

“What sort of access?” he asked.

“To everything, of course!” Edward’s words were a little slurred, but what they lacked in clarity they more than made up for in volume.

John held a warning finger to his lips before he could shout anything else.

“To the body,” the little man repeated more quietly. “To the area where it was found. To everything.” He lit another cigarette and blew smoke at the ceiling. “I’m not one for astrology and palm reading and all that heathen mumbo-jumbo, but there was a look in her eyes. A look that said, help me.” He reddened a little and squinted through his glasses. “I know I sound like I’ve lost my marbles, but I’m telling you, the police have missed something. I’m not saying she was murdered, necessarily…” He broke off, as though saying the word for the first time had surprised even him (it had certainly surprised – and delighted – John), but, after a sip of his wine, concluded, “…but I’d be astonished if it were the simple mishap the authorities believe.”

That was the moment at which John should have definitely made his apologies and rejoined the others at the bar. But instead, he grinned wolfishly at Edward and said, “David says we’ll not be able to film for a few days, and there’s not much to do round here, lovely old dump though it is. So why don’t we see if we can identify this troubling something while we wait?”

Even after several months of working together, John didn’t know if he liked Edward Lowe, but there was a look in the other man’s eyes just now that promised some entertainment over the next few days, and he decided that was enough to be going on with.

He twisted in his seat and waved to the barman. “Another bottle of this frightful plonk, when you have a moment, please,” he called, and drained his glass.

* * *

It was such a shame that, unlike trumpet players and malt whisky, hangovers did not improve with age.

John groaned as he gingerly rolled onto his side, trying to find the one spot on the pillow where his head was not pounding with an insistent beat and his stomach wasn’t cartwheeling like a particularly inept circus acrobat. He opened his eyes, but only reluctantly and with difficulty, checking quickly whether there was anyone unexpected lying beside him. There was not, which was both a relief and a disappointment, but he could see his cigarette packet lying on the bedside table. As he reached shakily for it, the events of last night began to trickle back to mind.

It had begun quite promisingly, at least. Edward Lowe was stubborn, fussy and convinced he was always right – just the sort to think he knew better than the police, in fact – but he was also surprisingly good company once a few glasses of atrocious red had loosened the permanent stick up his back.

“The thing is…” he had said (probably said, John mentally corrected himself; he wouldn’t be willing to swear in court to anything Edward had said after his sixth drink). “The thing is, there is a… discrepancy… which the police have failed to identify.”

Edward had definitely sat back after that, his hands crossed over his ample stomach, his face flushed red, cigarette ash falling on his waistcoat, looking quite Dickensian in a Joan Littlewood sort of way.

“So you said,” John had replied, a little unsteady himself. “But what is it specifically?”

“Ah…” Edward had sighed. “I’m not absolutely certain of that.”

He had no memory of the period immediately afterwards, but he suspected they had sat in the silence of the just-beyond tipsy, that wonderful extended moment when there was sufficient alcohol in the blood to lend a rosy glow to the world, but not quite enough to set the room spinning.

He did remember the barman standing by the table, informing them firmly that he needed to close the bar. Other than that, the evening was composed of fragments, tiny shards of memory which he found difficult to place in order; they were too brief and too similar, with too little information to create a useful timeline.

Edward tearing the label from the wine bottle and sketching on the back of it in pencil. Something to do with silver and ice. Jimmy Rae throwing bags of crisps across from the bar. Himself telling Edward about Sally, his ex-wife and – he could admit this only to himself and nobody else – the real love of his life, and how he’d missed her when she left him for the bloody insurance man. Edward thumping his hand on the table, over and over again…

Actually, no, that wasn’t right. That wasn’t from last night. That was happening now.

John opened his eyes and carefully turned them towards the door. It shook on its hinges as someone outside kicked it and shouted his name.

“John! John! Let me in! I’ve figured out what they missed!”

Of course it was Edward. Who else would be so cruel as to deliberately wake a hungover man at such a tragically early hour?

“Come in,” he called weakly, then stubbed out his cigarette and arranged himself in a manner which he hoped indicated a sick man best spoken to quickly and quietly, then left alone. He doubted Edward would even notice, though.

And so it proved.

“It’s not the missing shoes!” Edward exclaimed without preamble. “It’s the missing socks!”

John’s head – his health, even – was far too precariously balanced for guesswork. “What’s that, old boy?” he asked. “Missing socks? What missing socks?” He pressed a wan hand to his forehead and gave a small, but audible, groan. “You mean our late lamented lady friend of yesterday? But she wasn’t even wearing shoes, far less socks.”

“Exactly!” Edward strode across the room and stood over John’s bed. For the first time he seemed to notice the condition of its occupant. His nose wrinkled in disgust. “Shouldn’t you be up by now?” he said; then, clearly determined not to be distracted, continued, “You remember I said there was something they’d missed? That’s it. The police believe she kicked her footwear off in the water. But if she’d been hiking, or even walking by the reservoir, she would have been wearing boots.” He peered at John’s face, his eyes screwed tight behind his glasses, as though willing him to understand. “Or stout shoes, at the very least. Don’t you see? Nobody wears those kinds of shoes without socks. It just isn’t done. The only kind of shoe a woman would wear without socks or stockings is one with a heel! And who in their right mind would voluntarily walk across the moors in heels?”

It was a good point. Even in his current state, John had to admit that. He wasn’t convinced it was one that justified being roused from what he feared might turn out to be his death bed, though.

“So, she didn’t walk across the damned moors,” he said, and winced at his own sharp tone. Regardless of his possibly imminent expiration, there was no excuse for rudeness. “Perhaps she drove?” he continued, more gently.

“But she had to come across the moors,” Edward countered, becoming more animated as he paced around the small room. “Look, I’ll show you.”

From the pocket of his dressing gown – only now did John notice that he was still in his pyjamas – he pulled out a map. That was reason enough to take him seriously, or to admit that Edward was taking things seriously, in any event. John had never seen the man anything other than fully dressed before. The removal of his jacket and tie was, for him, akin to indulging in the sybaritic rites of the Polynesian natives. To appear in the bedroom of one of his colleagues in carpet slippers and dressing gown was a sign of previously unimagined agitation.

Edward spread the map – one of the colourful ones of the village which sat in a plastic container at reception – on John’s bed and traced a route with his finger. “You see? There’s no road she could have taken that leads to the reservoir other than this one, the one we came up yesterday morning. And that was closed on the night she died, so the scenery chaps could leave their lorries and whatnot parked and ready for shooting.”

John pulled the map closer and studied it for a second. He indicated a thinner, shorter line to the northwest of the town. “What about this one here, though?” he said, running his finger along its length to a small rectangle halfway between Ironbridge and the reservoir. In spite of himself, he was growing interested again. He peered down at the map key. “That’s a B road, and it ends in a car park,” he observed. “Perhaps she drove there, then decided to go for a moorland stroll?”

Edward shook his head emphatically. “I don’t think so. See, there’s a track marked as a scenic walk leading north from that car park. Why the devil would she ignore that and head west across the moors to the reservoir instead? No,” he declared firmly. “She must have walked across that unmarked and muddy moorland in footwear entirely unfitted to the job, and I refuse to believe that was done voluntarily. Something’s definitely not right here, John. I’m sure of it.”

John had no doubt there were several perfectly good explanations, but in his current condition, he couldn’t put his finger on one. In any case, even on their relatively short acquaintance, he’d come to know that tone of voice well enough to understand that Edward would not be swayed by anything so tiresome as mere argument.

Besides, it was odd.

So, he nodded and waved a hand towards the door. “Then why don’t we both get dressed and take a trip up to the moor?” He smiled and winced a little as the pain in his head flared up. “After breakfast and a couple of aspirin, that is.”

4

The morning was damp and cold, but Edward had woken up in an unexpectedly good mood. Generally, rising early left him irritable and ill-tempered, especially when, as now, he was involved in sub-par sitcom rubbish like Floggit and Leggit.

The reason for his good humour was obvious, of course. The previous night had been a waste of his time, it was true, and he wasn’t even sure why he’d asked John to join him. But the second he had opened his eyes, the matter which had been on the tip of his tongue all evening had miraculously shifted itself to the front of his brain, where it sat, fully formed and ready for expression.

He’d been delighted to discover that his brain hadn’t entirely atrophied after weeks of spouting the writers’ gormless claptrap. He was a little concerned, however, that he’d allowed excitement to overtake him to such an extent that he’d crossed the landing to John’s room without dressing, far less shaving.

It was a one off, though, not a sign of slipping standards. He finished his delayed shave, wiped his face and straightened his tie. He wasn’t sure yet exactly what the missing socks and shoes signified, but as soon as they’d popped into his head, he’d felt a strange pressure in his chest, tight but not unpleasant. They signified something important, he was certain, and that was a starting point, at least.

* * *

So good was his mood, in fact, that when he made his way downstairs to the George Hotel dining room, he was barely put out by the absence of kippers on the breakfast menu.

“Are the sausages fresh?” he asked.

“Just arrived from the butcher, Mr. Lowe.”

“Well, I suppose they’ll have to do. If you could make sure to have kippers tomorrow, though. Proper kippers, mind. None of that boil-in-the bag muck.” He wiggled his hand in mimicry of a kipper swimming upstream.

For once, they were quick to get his food out, and he was just about to tuck into the sausages, with bacon and mushrooms and two rounds of toast, when John walked in.

“John,” he beckoned, waving a fork in his direction, then, to the little blonde girl taking the breakfast orders, said, “Mr. Le Breton will be joining me. He’ll require cutlery.”

“If that’s not too much of a bother, my dear,” John clarified, as he slipped into the seat opposite Edward. “And I’ll just have toast and butter, and a coffee, when you’ve got a second.”

It was a measure of Edward’s current equanimity that he felt no annoyance when the girl beamed at John and bustled off to get his toast. It took her ten minutes yesterday to find out whether the ham was on the bone, he thought indignantly, but decided not to let that spoil his mood either.

“I’ve been thinking about the missing shoes,” he said, as the girl reappeared at John’s elbow and slid a mug of coffee in front of him. “We should trace her steps across the moor. Start at the car park and head straight for where I found the body.” The bacon was more fatty than he liked and he pushed it to the side of his plate with a scowl. “I looked at the map before I came down, and it can’t be more than a half-hour walk.”

The girl was back again, John’s toast in hand, and he took the opportunity to point out the failings of the bacon and request an extra sausage. He shook his head as he watched her wander off towards the kitchen. He’d have finished his breakfast by the time she came back, he was sure of it. But if John had asked… he gave a mental shrug. He would be the bigger man. Nothing could be allowed to derail this morning. Not when they had so interesting an expedition planned.

He’d always been fascinated by detectives, and policework in general. Since he was a boy, he’d been a keen student of famous cases. And when hostilities broke out in ’39, he’d spent a short time working with the military police before he’d been transferred to radio work and shipped out to Egypt. He often wondered how his life would have turned out had he kept working with the MPs. Would he have even gone into acting? Perhaps he would have stayed on past demob. Perhaps he might even have ended as something higher than a sergeant?

He allowed himself a small smile. He didn’t think a military career would have suited him, not really, but he would have liked to finish the War as an officer, rather than an NCO. Captain Lowe did have a ring to it.

“…boots with me, but Madge from wardrobe volunteered to look out wellington boots for the pair of us.”

John had been speaking, he realised, but he’d been paying no attention. Luckily, his meaning was clear enough.

“Splendid!” he agreed, with enthusiasm. “We should collect them, and then borrow a car and drive to the car park.”

John nodded. “Fine by me,” he mumbled through a mouthful of toast. “Madge said she’d leave the boots at reception. Wonderful girl, that. Such an obliging nature. I might see if she fancies a drink one night.” He pushed his plate to one side and lit a cigarette, with the faintest of smiles on his lips. “Though I have to ask – what are we hoping to achieve? Even if the poor woman was wearing heels, and even if they aren’t at the bottom of the reservoir, and even if we find them,” he went on, more seriously now, “it won’t prove any, ah… skulduggery has taken place.” He coughed as the smoke reached his lungs. “I bumped into David on the way downstairs, by the way, and the police have told him we can recommence shooting the day after tomorrow. They’re satisfied it was a terrible accident. The inspector left first thing, apparently. Which does rather beg the question; would we not be better taking the word of the professionals, and leaving this be?”

Edward shook his head. “The police are far too ready to write this off, in my opinion,” he declared with a grimace of annoyance. “Typical of the modern world, if you ask me. Everything’s so rushed, nobody takes the time to do their jobs properly.” He glared at the waitress as she bent over him and removed his plate. Totally forgot about the replacement sausage, he thought.

“More coffee, Mr. Le Breton?” she asked, pronouncing it “Le Britain”, which gave Edward a momentary stab of pleasure.

The mispronunciation evidently didn’t bother John, however. He simply shook his head. “No, thank you, Julie. It’s so kind of you to ask, though. I don’t know what I’d do without you. And do call me John. All my friends do.”

She reddened and smiled at him, then, with a quick wipe of her cloth, flicked a few crumbs from the table to the floor. “Just shout if you change your mind,” she said, and moved away towards the other guests.