Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

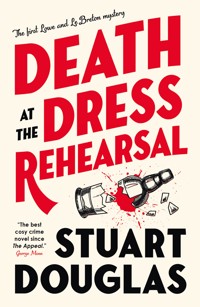

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Lowe and Le Breton mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

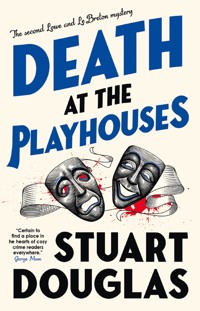

A second witty, fun, 1970s-set whodunnit in the Lowe and Le Breton mysteries series, featuring two ageing actors attempting to solve a murder after their famous co-star is found dead in a doorway outside the theatre in which they're performing. Nostalgic cosy crime that's perfect for fans of The Thursday Murder Club and Death & Croissants. It's 1971 and, in between filming seasons of Floggit and Leggit, ageing actors Edward Lowe and John Le Breton sign up for a short run of Shakespearean tragedies at the Bolton Playhouse. But, once in Lancashire, they discover they have been invited to join the theatre's repertory company for two reasons – because the company manager is keen to take advantage of the publicity surrounding their successful BBC comedy series, and because Sir Nathaniel Thompson, the much-lauded star of the show and knight of the realm, has been sacked for drunkenness. John fears an awkward scene, should Thompson – who he knew during the war – return to reclaim his job, but when the great actor's body is found, bludgeoned to death in a nearby alleyway, the unlikely crime-solving duo find themselves investigating another fiendish mystery that takes them from the northwest of England to the Netherlands, and which, rather inconveniently, seems to have John's ex-wife Sally at its heart. Death at the Playhouses is the second in The Lowe and Le Breton Mysteries series.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 551

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part One

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

Intermission

53

Part Two

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise for the Lowe and Le Breton mysteries

“Douglas brings a light touch to an intriguing mystery centred on two opposites, a grumpy old stager matching his wits with his urbane companion. Together they give a flying start to a new crime series.”

The Daily Mail

“Certain to find a place in the hearts of cosy crime readers everywhere, with its breezy prose, its witty observations and the often hilarious interplay between its two thespian leads – not to mention the cracking mystery at its heart. Stuart Douglas has just delivered the best cosy crime novel since The Appeal.”

George Mann, author of the Newbury & Hobbes series

“It was a joy to be in the company of these Dad’s Army detectives. I read the whole book in one sitting. Hugely enjoyable and lots of fun.”

Nev Fountain, author of The Fan Who Knew Too Much

“Glorious and ingenious! What a lovely start to what I hope will be a long-running series!”

Paul Magrs, author of Exchange

“A real tootsy-pop of a mystery thriller, with an irresistible conceit and enough twists and turns to bamboozle the most conscientious of armchair sleuths.”

Steve Cole, author of the Young Bond series

“Holmes and Watson by way of Arthur Lowe and John Le Mesurier; a wonderfully mismatched duo who you can’t help falling in love with.”

Amy Walker, Trans-Scribe

“Lowe and Le Breton are already shaping up to be the next great detective duo. If they don’t get their own TV series, it will be a crime.”

Kara Dennison

“Edward Lowe and John Le Breton are two of the most unique and disparate crime solvers you could find. Actors as unalike in their dispositions as their methods.”

Elizabeth Lefebvre, Strange & Random Happenstance

Also by Stuart Douglasand available from Titan Books

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Albino’s Treasure

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Counterfeit Detective

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Improbable Prisoner

Sherlock Holmes: The Sign of Seven

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: The Crusader’s Curse

Death at the Dress Rehearsal

DEATH AT THEPLAYHOUSES

The second Lowe and Le Breton mystery

STUART DOUGLAS

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Death at the Playhouses: The second Lowe and Le Breton mystery

Print edition ISBN: 9781803368221

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803368238

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: March 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Stuart Douglas 2025. All Rights Reserved.

Stuart Douglas asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Julie, always.

PROLOGUE

London, March, 1928

It was all he could do not to scream his rage into the policeman’s face. In his mind’s eye, he grabbed the fool by the throat and shook him like a puppy that had disgraced itself on the sitting-room floor.

Disgraced.

The word lodged in his head as though it had a physical presence, an actual depth and width and weight, as though it were actually floating behind his eyes, crammed in the space between them and his brain. He blinked to rid himself of it, but while his eyes were closed all he could see was the word, imprinted on the back of his eyelids like a photographic negative. His ribs ached where boots had smashed into them, and he could feel a bruise flowering on his cheek and a tooth loose in his mouth, but that word – that was the only thing that mattered.

“Do you understand what I’ve told you?” the policeman was asking. “Do you know why you were arrested?”

He ignored the questions. Never tell them anything, thatwas the trick. Wait until your lawyer arrives, then let him do all the talking. Give them nothing they can use against you later in a court of law.

A court of law.

Another blink, then another, and he was able to see something other than those terrible, terrible words. He couldn’t have that. Of course he couldn’t. Not a court, with judges and a jury – and journalists. And outside, photographers and men chasing the taxi, slapping their thick calloused hands on the windows, and women screaming your name like it was a curse.

Of course he couldn’t have that.

So not a lawyer, then. A lawyer meant a defence, and a defence logically required an accuser. He would not – could not – be accused of this thing.

Not in court. Not where people could see.

In need of an alternative, he looked around the room in which he was sitting.

A wooden table, with a wooden chair on either side. He in one and, in the other, facing him, the uniformed nobody who had wrecked his evening and potentially – only potentially, he reminded himself, fighting off panic – ruined his life.

On the table, his hands, scraped and bloody where he’d held them up to ward off the blows. In front of the policeman, an open notebook. In the policeman’s hand, a pencil, poised to write. He longed to reach across and snap that pencil in two.

Definitely not a lawyer, he thought again. A lawyer meant paperwork. A lawyer meant a record of what had happened.

There was somebody, though. A friend. Somebody who had told him that he made problems go away. “Nothing’s too much trouble for a pal,” he’d said. “There’s nothing I can’t fix for a pal.”

Finally, he looked the policeman in the eye. “If it’s not too much trouble, could you get a message to someone for me?” he asked.

PART ONE

1

London, October, 1971

So far as Edward Lowe was concerned, a day spent not working was a step closer to the poorhouse. Bills, he was fond of saying, needed paying, whether he was sitting idle or not.

He said as much to his agent as he spooned a third sugar into his tea and reached across the table for a Mr Kipling’s French Fancy. “I was up for the voiceover for these, if you remember, Alec.” He bit down on the pink fondant icing and chewed moodily. “Didn’t get it, of course.”

Alec Gent-Browning smiled and shook his head. “I’m sure you’d have been marvellous, Edward,” he said, “but you’ve gone on to bigger and better things, haven’t you? The days of worrying about paying the bills are behind you now.”

“Are they, though? It certainly doesn’t feel that way.” Edward was not in the mood to be placated. The second series of Floggit and Leggit had finished filming almost a month ago and he’d thought he’d be on to something else by now. But the phone had singularly failed to ring and when he’d dropped in on his agent to mention that fact, he’d immediately suggested they go out for lunch. That was worrying in itself. Agents only offered to pay for lunch when they had either spectacularly good or crushingly bad news to impart.

And Edward wasn’t the type to expect spectacularly good news.

All the way through an over-spiced mulligatawny soup and a barely adequate sole and boiled potatoes, he’d been waiting for the hammer to fall, but now, as they moved on to the coffee and petit fours, he wondered if he might have misjudged the situation after all.

“Of course they are,” Alec insisted. “You’re the star of the most popular comedy on television! How many people recognised you just walking from the car to the restaurant?”

Which was another problem, of course. The great unwashed suddenly seemed to think they were his close personal friends. He couldn’t pop to the shops for twenty Craven A and a copy of The Times without some scruffy creature in a football shirt and denims pushing their unshaven face into his and saying, “Alright, Eddie! How’s about an autograph?” He shuddered at the memory. Eddie!

But there was no point in complaining to Alec about that kind of thing. So far as he was concerned, fame was every actor’s primary goal, with riches a very close second, and the satisfaction of a solid career of good work a far distant third, if it were mentioned at all.

“Yes, I suppose so,” he muttered, and lit a cigarette.

“Denys Fisher are negotiating for a board game, I hear,” Alec went on, oblivious to Edward’s mood. “And…” He lifted his briefcase out from under the table and flicked back the catches with a flourish. “…there’s something here which will put a smile on your face, or I’m a monkey’s uncle.”

He pulled out a sheet of paper and pushed it across the table. “Floggit and Leggit has been nominated for Best TV Programme at the Film and Television Arts Awards, and you and John are both nominated for Best Actor.”

Edward grunted and glanced down at the letter. He supposed it was gratifying to be recognised by one’s peers, even if it was for this populist rubbish and not for something a little more highbrow. And he wasn’t sure how both he and John could be up for Best Actor. Surely there could only be one leading man on the show? Still, if there had to be another actor from the show honoured, he was glad it was John.

In truth, he and Le Breton had become good friends since the real-life drama of the previous year’s filming. Almost being murdered by the same lunatic harpy had a real bonding effect on people.

“Well, that is terribly kind of the Film and TV chaps, I must say. One doesn’t go looking for awards, of course, but if other people feel they’re deserved, well…” His voice trailed off with what he hoped was an appropriate degree of modesty, but then he remembered his earlier complaint. “Though a few offers of paying work would be better still,” he concluded, waving for a waitress to top up his coffee.

“Perhaps I can help you there too, Edward,” Alec positively beamed. “Mary, my secretary, took a phone call from young Jimmy Rae yesterday. I forgot all about it when the SAFTA letter arrived this morning, but it seems he knows I’m your agent and he was trying to get in touch with you about a bit of work. Theatre, he said. A month in Bolton over Christmas, and the possibility of a tour of Europe in the spring.”

Edward frowned. “Not pantomime, I hope. I know lots of actors do it at this time of year, but I draw the line at false bosoms.”

“No, it’s the legitimate stuff, according to Mary. Shakespeare and whatnot.” He handed Edward a scrap of paper. “She took his number and said you’d give him a call back to discuss it.”

“In which case, perhaps I will. It might be nice to go back on the boards for a bit. A pleasant change from this TV tomfoolery. Jimmy didn’t say what the specific role was?”

“Doesn’t look like it. But if it’s a month, that’s perfect timing for the SAFTA thing. The award ceremony is in February, so it’s likely to fall between your two runs, assuming that Mary picked Jimmy up right about the European tour.”

Edward leaned back to let the girl pour his coffee, then nabbed the final French Fancy. He bit into its yellow icing with a good deal more enthusiasm than he’d shown to the previous one. It had been years since he’d been abroad, and Christmas on the continent had a nice ring to it. Much more the sort of career he should be having, he thought to himself.

He did hope that Jimmy wasn’t acting the goat, though. In the eighteen months or so they’d been working together on Floggit and Leggit the young actor had shown himself to be talented on screen but prone to practical jokes and tomfoolery off.

Alec was chuntering on about some other client of his, but Edward had stopped listening. A sudden chill had descended on him, a sensation which reminded him strongly of a time when he’d rashly claimed to be able to ride a bicycle to get a part on a TV show. As soon as the words had come out of his mouth at the audition he’d regretted them; he could no more ride a bicycle than he could fly a plane, and that fact was bound to come out sooner or later.

Now he felt the same sick feeling in his stomach when he considered the casual way he’d said it’d be good to get back on the boards. True, unlike bicycling, he’d genuinely spent many years in rep, and had no fears of returning to live theatre per se. But Shakespeare? Had he spent too long in television, where he was able to have another go if anything went wrong, to tackle the world’s greatest playwright in front of a live audience? Was he kidding himself? Would this – as when he’d mounted the bike and immediately fallen over in an ungainly heap – end up as a humiliating disaster? Might it not be better to admit that possibility right now, back out while he still could, and stick with what he knew?

He looked down at the slip of paper Alec had given him and pushed it around the table in front of him with one finger. Then, decision made, he picked it up and slipped into his jacket. If he refused this opportunity, he might as well admit he was nothing but a TV hack now and be done with it.

He’d telephone Jimmy as soon as he got home then make arrangements for digs in Bolton.

2

Bolton, Lancashire, November, 1971

Edward was sure that the distance from their digs to the Bolton Playhouse was too far to walk, even if he wanted to – which he didn’t – and he was damned if he was paying for a taxi every morning and evening. Which made it all the more galling that theatres – unlike television companies – were unwilling to supply motor cars for the use of their cast.

He poured himself a fresh cup of tea and wondered, not for the first time, whether this entire expedition hadn’t been a grave mistake.

The telephone call with Jimmy had been something of a mixed bag, for a start. On the one hand, Alec Gent-Browning had been right; Jimmy had as good as offered him a job in the play he was rehearsing at the Playhouse. On the other, it appeared the director only wanted Edward as part of a duo with John.

“The director’s alright for an old geezer,” Jimmy had said on the phone. “But he don’t really give a monkey’s about the art. It’s all about the moolah with him, know what I mean?”

Truth be told, Edward wasn’t sure that he did. “He’s more interested in the box office takings than the performance?” he hazarded, and was pleased to have it confirmed this was indeed the case.

“Exactly! And that’s why he wants you and John. Add in me, and he can claim he’s got half the cast of Floggit doing Shakespeare. It’ll drag in the punters, he says.”

“Is that a prerequisite?” Edward had asked coldly, and, to his surprise, Jimmy hadn’t asked what the word meant.

“I reckon it is, Eddie,” he’d said. Eddie again, Edward grimaced inwardly. “But don’t get me wrong; Fagan’s no mug. You know how rep usually works – a right royal mix-up of fresh-faced drama-school virgins and drunken old hacks putting on one show at night while they rehearse another during the day, and a new play on every week. It’s a good way to learn your craft, I suppose, but it’s a bloody killer if you’re not used to it. I wouldn’t have put your name forward if there wasn’t a bit more to this than that.

“Nah, this is much more of a quality undertaking, it really is. Shakespeare only, for one thing. Proper rehearsal time, then a couple of weeks of King Lear and the same again of Hamlet. The rest of the cast are regulars, some of them have been with the Playhouse for years, but they’re all pretty decent. Fagan knows what sells, though, and he thinks for this that’s you and John and me on all the posters!” Jimmy coughed. “He actually wanted Joe Riley and Don Roberts and the rest, but they’re either already booked up or putting their feet up between series.”

“That’s probably wise. Neither of them are in what I’d call the first flush of youth. I must admit I feared for Donald’s life when he was hanging off that clock face last year.”

Jimmy’s laugh from the other end of the line had been long and loud. “Yeah, maybe it’s for the best they miss this one,” he said. “A month in the provinces might carry them off.”

“And there’s a European run afterwards, I think my agent mentioned?”

“So they’re saying! Amsterdam for a fortnight in the New Year, or maybe it’s February. Or March. Anyway, after Christmas.”

It had been as bad as speaking to John, Edward thought, remembering Jimmy’s vagueness with dates – just as the man himself appeared in the door of the dining room and waved across to him.

* * *

They had arrived at Mrs Galloway’s Home for Working Thespians (as it was advertised in The Stage magazine), the previous day on a bright, if cold, winter afternoon. After dropping their luggage in their respective rooms, they had decided to take a quick stroll around the neighbourhood before the chilly northern sun set.

It had been more than enough to cement Edward’s opinion that walking in the area was akin to strolling through London at the height of the Blitz.

As he settled himself into a seat in Mrs Galloway’s dining room the following morning, he elaborated on this point to John.

“Did you see the crowd of ruffians standing about outside that pub last night? And the way that dog bared its teeth at me. Not the dog’s fault, of course – a poor master will always lead to a poor dog – but I’d a good mind to take a stick to the brute who was supposed to be holding it. He looked more of a slathering beast than his animal.” He shook his head in remembered indignation, and spooned marmalade onto his toast. “We really should have asked the theatre to send a car to pick us up on our first day.” He sliced a sausage in half and dipped it into the pool of ketchup at the side of his plate. “I mean, God knows how much a taxi would cost, but it won’t be cheap, that’s for sure.” He chewed disconsolately and stared through the net curtains at the grey skies and steady, apparently unceasing, rainfall outside. “And even if we wanted to walk – which I don’t – it’s hardly the weather for it.”

“No,” John agreed, pushing his own half-finished breakfast to one side and lighting a cigarette. “It is pretty grim out there, isn’t it?”

“Sorry to intrude,” a loud voice cut in from somewhere behind Edward.

He turned and observed a fat man in an ill-fitting jacket at the next table.

“Brian Harvey at your service,” said the man. “I travel in brushes. Staying here for the night before I move on to Preston. But I couldn’t help overhearing. Am I right in thinking you gents will be making your way to the Playhouse after you’ve finished Mrs Galloway’s fine breakfast?”

Edward nodded carefully, wondering if the man had recognised them, and whether he would shortly be addressed as Eddie.

It seemed not.

“Because, if you are,” the man went on, “there’s a bus stop at the end of the street, and the bus from there goes all the way to the Playhouse, or near enough. You could get that and save yourself a fair bit of brass.”

A bus? The thought hadn’t occurred to Edward – who knew when he’d last been on a bus? – but, actually, why not? He looked across at John, whose face had creased in thought. Probably too working class for him, Edward thought with mean-spirited glee. A bus had been good enough to take his father to the factory every day, and it might be nice to follow in his footsteps. What was acting but a job of work after all?

He made a questioning sort of sound in John’s direction, and tilted his head to one side, inviting a response.

“Oh sorry, did you want the rest of this, Edward?” John asked, poking his plate across the table towards Edward. “Do help yourself, my dear chap. I’ve had enough, but you’re quite right – it does seem a shame to let good food go to waste.”

“I was simply wondering how you felt about getting the bus to the theatre,” Edward responded stiffly.

“Why not?” John laughed. “It’s been about twenty years since I was on a real bus, as opposed to one driven by Cliff Richard. It’ll be a lark!”

“You’ll need to get your skates on, mind,” the red-faced diner warned. “They only come once an hour and the next one’s due in twenty minutes.”

John dabbed his mouth with his napkin and rose to his feet, grinding out his cigarette in the ashtray as he did so. Edward made to follow his example, then, glancing at John’s abandoned plate, paused halfway out his chair and sat back down. John was right about good food. If there was one thing that the War – and the terrible news from Biafra – had taught everyone, it was not to waste food. He speared the pair of sausages on John’s plate and transferred them to his own.

Twenty minutes was plenty of time to polish these off, and still make the bus on time.

* * *

The bus was only half-full, but everyone on the downstairs deck appeared to be a middle-aged woman with a face like a heap of folded old dishcloths and a shopping bag on her knee. The noise of gossiping Lancashire voices was overpowering. Without a word, Edward followed John upstairs.

The bus pulled away from the stop as he was halfway up the stairs, causing him to fall backwards with a sudden jerk. Only a frantic grab for the railing prevented him from tumbling all the way back to the lower deck, and, even so, he banged the base of his spine painfully against the metal wall of the stairwell.

John, who had already stridden to the top of the stairs, looked back down and offered his hand, but Edward shrugged it off and pushed past him, then headed for the smoking area to the rear. Only when he had a Craven A lit did he speak to his friend.

“He did that on purpose, you know,” he moaned, rubbing the small of his back. “They must know they’ve not left enough time for people to get all the way to the top of the stairs, but they shoot off like Evel Knievel, nonetheless. I’ve a good mind to write to the company.”

John stretched his long legs out under the seat in front and said nothing. Edward couldn’t see his face as he turned away to look out the window, but he was sure he heard the sound of suppressed laughter.

“And don’t think I can’t see you laughing,” he snapped.

He was tempted to take further offence, but one of them had to be the bigger man, and given Le Breton’s childish sense of humour, it would need to be him. Even if he was, quite literally, the injured party.

“This should be an interesting morning,” he said in a conciliatory tone. “I’m very keen to discover what role I’ll be playing, for a start.” He coughed. “Obviously, one doesn’t like to be presumptuous, but, at the same time… well, they’ve not invited us all the way up to Bolton to play second spear-shaker from the left, have they?”

Secretly, he harboured the hope that Mickey Fagan would have the nerve to cast against type and offer him the part of Lear himself. But, realistically, he’d been in the acting game long enough to know the public was about as likely to accept a five-foot-five, bald King Lear as it was to accept a female one. Still, there was no reason one of the other meatier parts in the play – Gloucester, say, or Kent – couldn’t be on the less lanky side. So long as it wasn’t the bloody Fool.

John was still saying nothing; in fact, he’d yet to turn away from the window. It couldn’t be the view he was admiring – all that could be made out through the incessant rain were rows of identical boxy houses with, now and then, a brief flash of colour as a sad local park, with a single swing perched on top of a grass-free expanse of dirt, shot past. And he surely couldn’t be sulking. In fact, now he considered it, they’d barely exchanged a word since they’d left Mrs Galloway’s house.

“John?” he said, prodding him in the side. “I was just saying, it’ll be interesting to find out what parts they have in mind for us.”

“Actually, I already know,” John said, finally turning away from the window. “I’m playing the King.” His voice was flat and emotionless as he made this unexpected revelation, and Edward was surprised to see that, rather than the simpering half-smile which was as near as John ever came to a triumphant smirk, his face was creased with worry.

So worried did he look, in fact, that Edward even forgot to ask how John knew about the casting, nor did he immediately remember to be annoyed that he’d predictably been overlooked for the part of Lear.

“What on Earth’s wrong?” he asked.

In reply, John pulled a sheet of folded, off-white paper from his jacket pocket and handed it over. It was a telegram, apparently from John’s agent – Edward recognised the name of a well-known agency in London – which contained only two sentences.

KING LEAR CONFIRMED. STOP. DID YOU KNOW YOU ARE REPLACING NATE THOMPSON IN ROLE? STOP.

There was nothing else, and Edward handed it back with a shrug.

“Nate Thompson, Edward,” John said, tapping the name on the telegram. When Edward continued to look blank, he went on, “Sir Nathaniel Thompson. That’s who we – I – am replacing in this damned show.”

Well, that was slightly clearer. Edward knew Sir Nathaniel Thompson, of course. Or knew of him, at least. A few years older than he and John, Thompson was an actor of a different stripe altogether, Edward was not ashamed to admit. A giant of a man, both physically and professionally, Thompson was a contemporary of John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson, and cut from the same cloth. Decorated for outstanding but still secret heroics in the War, he’d played all the great Shakespearean roles by the time he was thirty, had been knighted by forty, and had three marriages and a string of very public affairs behind him by the time he marked his half-century. If John was stepping into shoes vacated by the great Sir Nathaniel, no wonder he looked so glum.

Still, it was hardly a cause for wailing and lamentation. “In some ways, that’s quite a compliment, really, when you think about it,” he offered, in what he felt was a commendably good-natured and encouraging tone. “Obviously, Fagan thinks you capable of filling the gap left by Sir Nathaniel. Unless it’s just because you’re tall enough to fit the costumes, of course,” he added, with a smile (he was only human, after all).

John was plainly unconvinced. He grimaced and shoved the telegram back into his jacket pocket. “I’m afraid you’re missing the point, Edward,” he said mournfully. “Not your fault, though. The thing is, that telegram was waiting for me after breakfast and, while you were upstairs changing your shoes, I telephoned London for more information.” He sighed, but not in his usual way, as though he wished to communicate he was too fatigued to cut the top off his own egg. Instead, it was a sound which seemed to come from the depths of his soul, a long, heavy breath of anxiety and concern which crumpled his face like a discarded paper bag. “Thompson was sacked, you see. Kicked out of the company for continual drunkenness and for missing multiple rehearsals.”

“And? I have to say, knight of the realm or not, his feet wouldn’t have touched the ground if I’d been running things either.”

“Yes, but this is the third time he’s been sacked for the same reason and, every other time, he’s gone on a spree for a day or two, then come back to the theatre, suitably chastened, and been given his job back.”

“Ah, and you’re concerned he’ll turn up in a day or two and expect the same treatment? Well, I wouldn’t worry. We’ve signed contracts, everything is done and dusted, and, even if he does come to Fagan, cap in hand, he’ll have no choice but to send him packing.”

“I’m sure you’re right, Edward,” John said, no happier than before. “But there’s bound to be a scene. And I do so hate scenes.”

That was hardly news to Edward. Over the previous eighteen months he’d watched his friend avoid confrontation with an almost religious zeal. He had accepted every script change and directorial idiocy without complaint, and gone out of his way to ensure that any potential source of conflict was nipped in the bud before it had a chance to flower. In fact, Edward had remarked to Bobby McMahon, the main writer on Floggit, that if Madge Kenyon, the mad killer they’d caught the previous year, hadn’t banged him on the head with her gun, John would probably have let her shoot him, just to avoid any unpleasant social awkwardness.

“And there’s more to it than that. It could all turn extremely difficult.” John twisted in his seat, a look on his face which Edward would have described as anguished if he’d thought the other man capable of so violent an emotion. “We were friends once upon a time, you see. Well, not friends really, more acquaintances who frequented the same pubs and knew the same people.”

Which sounded very like a definition of friendship to Edward, but he realised it wouldn’t do to say so, and so he remained silent as John rabbited on.

“It was a long time ago. Before the War, almost. We lost touch after that.” He frowned. “But even so, it’s going to be terribly difficult if he turns up tomorrow, looking for his job back, and he finds me already with my feet under the table.”

“You think he might cut up rough? Come at you with his fists flying?” Edward was enjoying John’s very obvious discomfiture, he couldn’t deny it. It was so out of character.

“Well, no, not that sort of thing.” John paused in thought, then grimaced. “Though he did have quite a temper back then, now I come to think on it. And he is built on fairly industrial lines. He’s got a good four inches on me, and a couple of stones too, I shouldn’t wonder.”

Now he fell silent, concentration writ large on his long face. Edward considered whether to enquire further, but John turned away, clearly wishing to be left alone with his thoughts.

Edward lit another cigarette, and left him to it, passing the time by counting the stops to the Playhouse, and hoping they didn’t miss it through the filthy bus windows.

3

Seen from the street on which Edward and John stood, the Bolton Playhouse had an air of defiant but elderly grandeur. Rising three storeys high from the square which it dominated, the chipped paint of its frontage was creamy grey in colour, with three separate entrances spaced along the length of the stuccoed facade. A central stone balcony served as a heavy line beneath several tall windows, which allowed plenty of light to fall into the theatre. Solid, if crumbling, Victorian brickwork was decorated with classically inspired columns, cornices and little half-circle windows, which John had a feeling were called architraves (unless that was what they called bishops in the ancient church; he’d been less than attentive in Religious Studies at school, he had to admit). It faced onto a cobbled square, currently empty save for a heavyset man in a donkey jacket who moved away as soon as he realised John was looking at him.

He thought the theatre looked marvellous, for all that each individual element of the building appeared in need of repair of one sort or other.

“The place is falling to bits,” Edward complained at his elbow, glaring at the theatre as though it personally offended him. “This is one of the oldest rep theatres in the country, you know,” he went on, the affront plain on his face. “Yet the local council have allowed it to fall into this sorry state.” He shook his head. “Sometimes I despair, I really do.”

“I rather like it,” John replied equitably. “It looks lived in. And apparently, there’s quite a decent restaurant inside.”

“Is there really?” Edward brightened a little and wandered across to peer at the glass-covered noticeboard at the side of the main entrance. “No sign of a menu that I can see, but that’s probably all to the good. Keeps the riff-raff out, for one thing.” He frowned suddenly and leaned closer to a stone structure at one side, next to a revolving door marked Box Office. An empty noticeboard was bolted to its side. “That’s odd, wouldn’t you say? You can see where there was a poster here…” he tapped the glass, indicating a drawing pin which still held a scrap of paper to the cork board behind it, “…but it’s been taken down.”

Still frowning, he scurried round John and stepped back into the square, the better to examine the front of the main building.

“And look there, at the marquee,” he said, indicating the gigantic poster which was emblazoned across the front of the building, just above the central balcony. “It says King Lear clearly enough, but someone’s painted over the cast list.”

John looked up as requested. Sure enough, a rectangle of white paint covered the lower third of the poster, obscuring the area which would usually have contained the names of the more prominent, or at least most well-known, of the cast. He thought he could make out the top half of the word “Starring” above the level of the paint, but nothing more.

“Obviously the sign they had would have had Nate Thompson’s name on it, Edward. They could hardly keep advertising him if he’s not going to be in it.”

The thought plunged him back into the depression which the sight of the Playhouse had momentarily lifted. What would he say to the man if he turned up at the theatre? He’d been rehearsing opening lines, picturing whole conversations, since he’d spoken to his agent, but still he had no idea how to handle matters if it became necessary.

Edward, however, was still focusing on the defaced marquee.

“Jimmy definitely said that this man Fagan intended to boost sales on the grounds of our involvement. How can he hope to do that if he’s not even advertising our presence? He’s had plenty of time to put up a new banner.” He eyed the building with distaste. “I knew I would come to regret doing this. Corners being cut, evidently.”

He hefted his umbrella and pointed towards the central doors of the main building. “Shall we head inside and find someone to speak to?”

John could see no reason not to, and – shrugging off his sense of impending doom – he trotted up the steps and through the door into the theatre. Edward’s complaints notwithstanding, it wasn’t in his own nature to brood for long. Besides, there was nothing quite like the first day on a new job in a new town.

* * *

The air of faded opulence John had noted from the street continued inside the theatre. Great swatches of purple and white paint covered the walls from floor to high ceiling, but the briefest moment of closer inspection picked out cracks which zigzagged across the plasterwork like forks of lightning. The thick carpet looked from a distance as though it had been expensive once but, like the paint, it had seen better – far earlier – days. Even the gold paint of the banisters which ran down the side of the auditorium was chipped. There was an air of… tiredness was the best word he could come up with… all around. Nothing was fresh, and the very air smacked of old triumphs long forgotten.

“It’s like something from a second-rate Roman orgy,” Edward grumbled at his side, clearly determined not to be jolted from his irritation. “Delusions of grandeur, I call it.”

John smiled as the image popped into his head of the portly Edward swaddled in a Roman toga, his little bald head topped with a laurel wreath, directing the participants at an orgy on how to conduct themselves correctly, and lecturing the younger people there on how much better orgies had been when he was a boy. Perhaps he should suggest they do something like that as a dream sequence on Floggit. The thought amused him no end until he realised Edward was staring at him and tapping his foot in irritation.

“You would think someone would be here to greet us,” he said.

Now he came to think about it, it was surprising there was nobody in the foyer to meet them. Actually, there was nobody around at all. The box office was obviously closed, but they were to meet the rest of the cast on the stage, and he’d rather expected someone to be at the entrance to look after them and show them the way.

Edward cast him one of his long-suffering looks and muttered that he would see if he could find anyone. “Just stay here, and I’ll rustle up an ASM or something. But I must say, it’s not the most promising start.”

He pushed his way through a set of double doors and disappeared into the theatre. John watched him go and returned to imagining him as Nero, playing a fiddle while the Groat Street Market burned.

He really would need to have a word with Bobby about that when they got back to Floggit. He’d always rather fancied playing Caesar and, if Donald Roberts wasn’t born to play the bumbling Claudius, then nobody was. He was still matching up Roman Emperors to Floggit cast members (Jimmy Rae as Caligula, perhaps, or would the elderly Scottish Joe Riley be funnier?) when Edward reappeared through the double doors and beckoned towards him.

“Fagan and the rest of the company are waiting for us on the stage, apparently,” he said. “According to the stagehand I spoke to, everyone was here half an hour ago.” He tutted and glared around the foyer as though looking for someone to blame for the mix-up. “I did explain that we’d not been told about that, but he didn’t seem bothered.” He dropped his voice and leaned towards John, holding the door open with his foot. “I popped my head around the door but, so far as I could see, everyone was reading their newspaper and drinking cups of tea, so I don’t think we’ve missed anything important.”

He turned on his heel and pushed the door fully open. “It’s just through here,” he said over his shoulder, letting the door swing shut behind him in his haste to be no later than they already were.

John, still mentally picturing Edward in a toga, followed at a more sedate pace. Plenty of time for being punctual tomorrow – first impressions counted, and he wouldn’t want people to get the wrong idea. The last thing he wanted in a new place was for people to think of him as an industrious sort. That wouldn’t do at all.

4

In person, Mickey Fagan was nothing like Jimmy Rae had described him. Jimmy had called him a wide boy when describing his plans for the show, and his desire to bring as many Floggit cast members together as he could had undoubtedly lent weight to that description, but, in the flesh, he was far from the skinny, flashy tearaway that Edward had expected.

Instead, he was a portly, red-faced man of middle years, with heavy bags under his eyes. What hair he had was parted an inch above his left ear, and combed across in an unconvincing and ill-advised attempt to cover a wide expanse of otherwise bald scalp. Still, he smiled with what appeared to be genuine pleasure when Edward and John entered the auditorium from the lobby.

Fagan was standing on the stage, at the centre of a small group of people. As he made his way down through the stalls, Edward recognised Jimmy, who waved and shouted a greeting, but most of the other faces which turned in his direction were strangers to him. He thought perhaps he recognised one older lady, but her name remained elusively out of reach.

“And here come two instantly recognisable fellows!” Fagan announced grandly as Edward followed John up the stairs to the stage. “Before I introduce our motley crew, I’m sure we’d all like to welcome Edward and John to the team.” He started to clap in a slow, exaggerated manner and, a little reluctantly it seemed to Edward, the others followed suit. The effect was more pitiful than welcoming, he thought. He’d half a mind to say something.

But it wouldn’t do to appear churlish; he knew how insular established rep companies could be. Besides, first impressions were important, and they would be working together for some time, after all. “Good morning, everyone,” he said. “I think I can speak for John when I say how delighted we both are to be here, in this glorious old lady of the theatre.”

He realised that, as he’d been speaking, he’d been looking across at the older actress he’d thought he’d recognised, still subconsciously trying to bring her name to mind. She grunted loudly as he finished and glared indignantly back at him. He did hope he hadn’t been misheard. “The Bolton Playhouse, I mean, of course, not any of our more… eh… experienced colleagues,” he added quickly. But, if anything, the clarification seemed to annoy the old woman even more.

“Since you appear to be directing your words to me, Mr Lowe,” she said, her eyes narrowed and cold, “I may as well be the first to introduce myself. Alice Robertson. I play Goneril, and most of the minor female roles.” She smiled and held out a hand in John’s direction. “Pleased to meet you, Mr Le Breton,” she said, in what Edward felt was a very pointed manner.

“Oh, do call me John, please,” John simpered. It was the only word for the way he billed and cooed over the outstretched hand. “And the pleasure is all mine. My mother and father took me to see your Ophelia at the Old Vic in 1915. I shall never forget how wonderful you were in the role. You never do forget your first time seeing a truly great Hamlet, do you?”

The old lady positively beamed at John. “How kind of you to say so. And how lovely of you to remember one of my former glories!” She gestured towards the stalls with a wave of her hand. “Though those days lie in my distant past, I fear.”

“Not at all, my dear,” John began, and would no doubt have gone on to further flights of flattery had Fagan not interrupted him.

“And having met our Goneril, let me introduce our Cordelia.” From behind Alice Robertson, a figure which Edward had assumed was an under-sized boy stepped forward. “Judy Faith,” Fagan went on, “meet Edward Lowe and John Le Breton.”

Judy Faith was petite and blonde, with wide brown eyes and hair cut in what Edward would have called a short back and sides. She was wearing jeans with an enormously wide cuff and a T-shirt with a peace sign embroidered on it. Any wonder he’d thought her a boy. She giggled and wiggled her fingers in Edward and John’s direction. “Pleased to make your acquaintance, guys,” she said, and giggled again.

Edward wondered what he’d let himself in for. Alice Robertson was plainly too old to be playing Goneril, even if she was the eldest of Lear’s three daughters, and this chit of a girl, while at least the right age for Cordelia, appeared to be an actual child.

“How do you do?” he said carefully, considering how best to enquire about her experience – and her age.

But John once again took it upon himself to be ostentatiously charming. “How delightful to meet you, Judy,” he said, smiling and waving his cigarette in a languid half-circle. “I must say you’re frightfully young to be playing such an important part. You must either be precociously talented, or the world’s most youthful-looking twenty-five-year-old.”

He chuckled, and the girl laughed. “I’m twenty-one, you cheeky bugger!” she said.

“Judy was a hostess on Ready Steady Go! when she was fifteen, and then she did some work for Mary Quant,” Jimmy Rae interjected. “She was voted one of the faces of 1971.”

Edward knew that Ready Steady Go! was a music show of some kind, but the name Mary Quant rang no immediate bells. Perhaps she was one of the new female TV producers? There were a lot more of them nowadays, and it was difficult to keep up with them all.

He nodded in Jimmy’s direction as though he knew exactly who she was – it didn’t do to look ignorant of the movers and shakers, as he’d heard the new wave of TV types described the other day – but any further discussion of Judy Faith and her career was cut off in any case, as Mickey Fagan called forward another figure from the crowd around him.

“And the last but definitely not least of Lear’s children. Our Regan, Monica Gray.”

He thought he’d recognised the name when he’d seen it in the cast list, but when Monica Gray walked towards him and shook his hand in what Edward thought was rather a masculine manner, he wasn’t sure if they’d ever met after all. Tall for her sex, she towered a good three or four inches over him, so that he risked a crick in his neck as he peered up at her. Her features, even allowing for being seen at such an unflattering angle, were cold and hard, with small, flinty eyes set in a face which appeared to be made entirely of thin skin and sharp bone. Her mouth was equally small and currently pursed tight. She was wearing black flared slacks and a white shirt, open at the collar, which added to Edward’s sense that this was not the most feminine of women. Judy Faith had seemed like a boy purely because of her hairstyle and clothes, but Monica Gray exuded an unfeminine strength. He could well imagine her running a servant through with a sword, as Regan did in the play.

When she spoke, though, he realised that not only did he know her, but he had also worked with her before. Where her physical appearance bordered on the manly, her voice was soft and delicate, and he was put in mind of something John had said when describing a woman he’d heard singing in one of his seedy jazz clubs. A voice like honey pouredover sugar, he’d said, and it fitted Monica Gray perfectly. He knew it at once, and could even – unusually for him – recall exactly where from.

“1963,” he said. “An episode of The Avengers. You were playing a Chinese assassin, and I was the politician you’d been hired to kill. You crushed me between two giant playing cards in the first act!” he complained, but with a smile, in case she thought he was being serious.

She returned the smile, and the action immediately softened her face. “I-Ching cards, actually,” she said.

“You were very striking, even under all that awful yellow make-up,” replied Edward gallantly. “I could hardly have forgotten you.” He took a step back, in order to see her better, and was struck by just how much a smile changed her face. Where at first he’d thought her features hard and cold, now they seemed warm and friendly. Her eyes twinkled and her fine cheekbones framed her face perfectly.

“And I’m her husband,” a harsh voice said from somewhere behind her, as a hand appeared on each of her shoulders and manoeuvred her to one side. The speaker emerged from behind her. He was a broad-shouldered man, taller than Monica, with an extravagant moustache which spread bushily from the usual place on his top lip all the way to his earlobes. Overcompensating for something, Edward thought maliciously. “Her agent, too. Michael Gray at your service, Mr Lowe,” the other man said, pressing a rectangular business card into his hand.

Edward glanced down at it. Michael Gray – Theatrical Agent it said, in a font so florid as to be almost unreadable. He tucked it into his jacket pocket and shook the man’s hand. “Pleased to meet you,” he said.

It appeared that the remainder of the crowd gathered on the stage were of minimal importance; at least, Mickey Fagan chose not to introduce them individually. “And you know Jimmy Rae, of course,” he said. “He’ll be playing Edmund.”

Jimmy gave a mock salute and grinned broadly. “At your service as usual, Eddie.”

“Edward,” Edward muttered irritably, but he suspected nobody heard him.

Instead, while John did his usual hail fellow, well met act with the Grays, Mickey Fagan stepped back into the light and clapped his hands together. “But, of course, I’m forgetting one other terribly important member of the company. Peter Glancy, who you may remember from a certain well-known detective series in the early years of ITV, is at the dentist this morning, but he’ll be back in time for rehearsals, never fear!”

Edward did vaguely remember him, or the series at least, though for the life of him he couldn’t remember what it was called. A man’s name, he thought, something like Fabian of the Yard, but not that. He had the faintest memory of a stocky man with broad shoulders and Brylcreemed hair, and a lot of scenes shot at night with the Thames in the background, but he doubted he could have picked its star out of a lineup, even if everyone else was a midget. Such is the fleeting nature of fame, he thought smugly, then felt bad for thinking it.

“I was in an episode of that, you know,” John exclaimed, with delight. “I don’t think I had any scenes with Peter, but dear Pat Troughton was in it, and we ended up drunk as lords in the Flamingo Club that night, watching Sarah Vaughan singing.” He sighed, and said more quietly, apparently for Edward’s ears only, “I was supposed to be taking Sally for dinner after filming that day, but Pat convinced me to go for a quick one before I met her, and one thing led to another… No wonder she eventually got fed up of me.”

His voice tailed off into an unhappy silence. Edward had heard John speak about his ex-wife Sally several times, but only when they were particularly deep in their cups. Drunk or sober, though, the memory of their married life always left his friend melancholy. Before John could descend further into misery, Edward clapped his hands together in imitation of Fagan a minute earlier. “It’s lovely to meet you all,” he said loudly and, he hoped, convincingly. “And it sounds as though there are some old friends in the cast, which is always a bonus.” He smiled. “John and I can’t wait to start working with you all, so if someone could point me to the nearest kettle, I’ll make us all a cup of tea and we can kick things off!” Forced jollity never came easily to him, and he felt sure everyone would spot his lack of sincerity, but, if they did, they said nothing; they just joined in and amplified his clap into a round of applause with what he chose to view as genuine enthusiasm.

There was no doubting Mickey Fagan’s enthusiasm, at least.

“Well bloody said! Let’s get to it!” he cried with a flourish of his hands. “First night is on Sunday coming, so we’ve only got a week to get Edward and John up to speed.” He looked at his watch. “Let’s meet back up here in forty-five minutes and we can start blocking out some scenes.”

The various actors and actresses moved off in small groups, one or two of them casting a glance in the direction of the newcomers. Fagan put an arm around Edward’s shoulders and guided him towards the back of the stage, where John had already gravitated to speak to a young woman he didn’t recognise. He did his best not to stiffen too obviously at Fagan’s heavy touch – it did seem quite a liberty to be manhandling him on such a short acquaintance – and maintained his smile, which was starting to make his face ache, until Fagan introduced him to the young woman.

“We won’t be starting rehearsals in earnest until ten thirty, but, in the meantime, I thought you might like to meet the most important person in the whole theatre,” the red-faced man said with another flourish. “Edward Lowe, meet Alison Jago, my assistant stage manager, without whose constant efforts we’d have ground to a halt a long time ago!”

Up close, Alison Jago seemed more girl than woman. Like Judy, her blue jeans were widely flared out at the bottom and decorated with hand-stitched flowers and butterflies, while her T-shirt had the image of a banana printed on it. Edward doubted she could be more than nineteen or twenty, but she held out her hand confidently enough, and her grip was solid. Besides, he knew that ASM was a good entry point into the theatre for students and the like, so they tended to be on the younger side.

“How do you do?” she said, with a warm smile. She was actually quite striking-looking, Edward decided, with skin the colour of milky coffee, and black hair cut into a sort of pageboy style. Her large, round eyes were brown and blinked slowly as she spoke. She wore no make-up, he was pleased to note.

“Jago? Any relation to Robert Jago, the playwright?”

“My father.”

“I’ve never worked with him, but I saw his A Stitch in Crime at the Lyceum, oh, ten years ago, it must have been.” Edward turned around. “Do you know him, John?”

John shook his head. “I know of him, of course. He’s at the BBC now, isn’t he? But, no, I’ve never worked with him.”

“Neither have I,” Alison said, a little too quickly. “But John was just telling me that you and he first worked together not long after the War.” She laughed, exposing small, very white teeth. “That’s before I was even born!”

“Alison was kind enough to say that we didn’t look old enough,” John murmured, evidently pleased by the flattery. Though, had he even recognised it was flattery, Edward wondered?

“Well neither of you do,” the girl replied with every sign of sincerity. “Just remember that if you need to know anything about this place – anything at all – come and see me. If I can help, I will.”

John gave her a grin. “I believe Edward suggested the first thing we needed was a cup of tea. Perhaps you could lead us to the nearest kitchen and tell us a little more about yourself, and about the Playhouse.”

With what was almost a bow, he gestured off stage and then, as Alison Jago started down the stairs, followed in her wake. Edward, with a shrug, told Fagan they would be back shortly, and trotted after the pair of them.

5

John hadn’t thought about Sally for months, but all it took was mentioning the time he’d stood her up for dinner for her face to dominate his thinking for a time.

He thought back to what had been a gloriously sunny afternoon in 1936, one of a run of the scorchingly hot summers that were more common before the War. It was shirt-sleeve weather, even in those days when failure to wear a jacket was as good as an admission of criminal intent. Shirt-sleeves and bottles of beer weather, beneath a sun that burned the grass yellow and brown, and made the air shimmer in the heat. Shirt-sleeves, bottles of beer, and a bloody great shed to be shifted from one side of the garden to the other.

It wasn’t even his shed. Fred was the name of his shed-owning pal, a one-armed ex-soldier he’d met at the bar of some dance or other. He lived in the upper flat of a four-in-a-block terrace – one of the Homes Fit for Heroes that Lloyd George had promised to the men who’d left bits of themselves in France during the Great War.

“Give me a hand, there’s a good chap,” Fred had said the night before, holding out his stump and laughing fit to burst. “I seem to have mislaid mine.”

“Of course,” John had replied, joining in the laughter. “Happy to help.”