Made in America, Sold in the Nam E-Book

9,43 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Reflections of History

- Sprache: Englisch

Hope and Healing For All Who Have Been Touched by War

For Viet Nam Vets: an opportunity to verify their experiences against experiences of others leading to validation and perhaps even an airing of their suspicions and fears about themselves. No matter how long it has been, healing is possible.

For Families of the KIA: peace and understanding about the experiences of their loved one and if they have letters from their loved ones, perhaps a way to fill in what could never be spoken.

For Adult Children and Spouses of Vets: empathy for their war experience, in spite of whether or not there has been communication about how it really went down.

For Vets of Recent Conflicts: a shortcut to understanding the overall experience of war and how one copes with its indelible marks. Discover the commonality of those who have endured their time as warriors.

For Society and Generations to come:

Learn what really happens during a modern military conflict. A plea for wisdom in how we deal with other peoples on Earth. A chance to break the cycle of doing the same things and hoping for magically different outcomes.

"That there is conflict and confusion over how we are to view the Viet Nam War and how we are to feel about those who sacrificed for this effort, makes this book all the more important. These pieces give the average person insight into what really happened to those that served and what they thought that they were trying to accomplish. There is some personal truth, buried emotion, and a few heroes in their own right."

--Tami Brady, TCM Reviews

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 605

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Ähnliche

MADE IN AMERICA, SOLD IN THE 'NAM:

A Continuing Legacy of Pain

Second Edition

Ed. by Rick Ritter and Paul Richards

Book #2 in the Reflections of History Series

Modern History Press

An Imprint of Loving Healing Press

Made in America, Sold in the Nam: A Continuing Legacy of Pain, 2nd Edition.

Book number two of the Reflections in History Series

Second Edition by Modern History Press, September 2007Copyright © 2007 by Rick Ritter and the Estate of Paul Wappenstein, Jr.

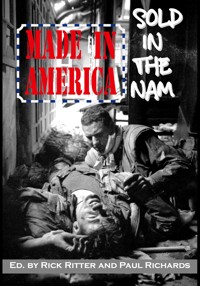

Cover photo © 1968, 2006 Stars and Stripes. Used with permission from the Stars and Stripes, a DOD publication.

No part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Made in America, sold in the Nam : a continuing legacy of pain / ed. by Rick Ritter and Paul Richards. – 2nd ed.

p. cm. – (Reflections of history series; v. #2)

Originally published: compiled and edited by Paul Richards. Fort Wayne, IN : DMZ Pub., 1984.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-932690-24-8 (casebound laminate : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-932690-24-7 (casebound laminate : alk. paper)

1. Vietnam War, 1961-1975–Literary collections. 2. Vietnam War, 1961-1975–Psychological aspects. 3. Veterans' writings, American. 4. Vietnam War, 1961-1975–United States. I. Ritter, Rick, 1948- II. Richards, Paul, 1944-1984.PS509.V53M33 2007810.8'0358–dc22

2006030125

Distributed by: Baker & Taylor, Ingram Book Group

Modern History Press is an imprint of Loving Healing Press 5145 Pontiac Trail Ann Arbor, MI 48105 USA

http://www.LovingHealing.com [email protected]

Fax +1 734 663 6861

M o d e r n H i s t o r y P r e s s

Dedicated to all the childrenwho will be warriors of peacerather than of death and maiming.

Proceeds from a portion of the sale of this book willbe donated to the foodbank of theLincolnshire Church of the Brethren, Ft. Wayne, Indiana

Reflections of History SeriesFromModern History Press

This series provides a venue for contemporary authors who have lived through significant times in history to reflect on the impact of events and lessons they learned from them.

1. My Tour in Hell: A Marine's Battle with Combat Trauma by David W. Powell

2. Made in America, Sold in the ‘Nam: A Continuing Legacy of Pain (2nd Edition), Ed. by Rick Ritter and Paul Richards

3. F.N.G: A Novel by Donald Bodey

“Those who cannot remember the pastare condemned to repeat it.”George Santayana in Life of Reason (1905)

Modern History Press is an Imprint of Loving Healing Press.

Soldiers… in Their Own Words:

Uncut and Uncensored

“While in the Nam, a change began to occur that would continue for years afterward. I began to see how I'd been lied to, how the indoctrination had been a veiled attempt to charge us up to do the impossible for the ungrateful.”

—Charley Knepple (1948-1997), US Army veteran

“Combat burdens every warrior with guilt, anger and fears. The Viet Nam combat veteran is burdened also with the guilt, anger and fears of America. Sometimes he has been charged with crimes. Other times he has simply been ignored as a symbol of embarrassment. Very seldom has he been welcomed, honored and embraced. A warrior so burdened can never escape the battlefield.”

—Chaplain Cephas D. Williamson, VA Med Center, Ft. Wayne, IN

“My mind was like a blank tape on a tape recorder, with a low or underlying hum of death and destruction as the rewinding of the tape. I had no time out there to rationalize or wonder, or just scream from fear. If I would have rebelled against the war, any time in Viet Nam, any more than I did, the career officer would surely have done me in, one way or another.”

—Nick Rizzo (1948-), US Army veteran.

“The ground troops in Nam were given the type of training that made them killers. They were taught to react to certain types of stimuli in a physically aggressive manner. What seems to unnerve the people of this land is that the same Nam vet is fully capable of using those same destructive skills against the general population.”

—Rick Ritter, MSW, USMC veteran.

“The soldier is a non-person, an alien, a thing expected to function, while everything around him is strange and lacking in meaning. His view of his surroundings is startlingly expressed in the phrases ‘The Nam’ and ‘The World’; Viet Nam is, in his perception and experience, someplace removed from the real world.”

—Stephen Howard, M.D. US Army surgeon veteran

“Rape does not need any elaborate political or socio-economic motivation beyond a simple and general disregard for the bodily integrity of women, plain and simple. The very intensity of maleness that the military demand can only be seen as the beginnings of the power addiction that ultimately leads to female subjugation—rape.”

— A Woman (non-veteran)

“Torture, rape, and murder: ‘Access and opportunity’ are only two of the prerequisites. There has been a lot of rape in wars; I keep thinking what it would have been like to be Vietnamese. They never sold their sisters.”

—A Viet Nam Veteran (male)

“On Sunday, the last day of the exhibit, during the reading of the additional 110 names for the wall, I saw a dear friend of mine crying… I too started to sob. He had a right to weep, all the rows of names on this ‘WALL OF LOVE’ and now more to add. God please make us remember what happened so it is not forgotten and this horrible waste of precious human life will not happen again.”

—Karin A. Hancuff, bereaved relative of a veteran

“The Wall is a sphinx that will endlessly pose its riddle to those who seek power and will, let us pray, devour those who cannot answer or who answer poorly. It is a sear upon the monumental landscape of our capital; like all scars, it is at once evidence of a wound's healing and a reminder of its hurt.”

—Rev. Michael Scrogin

“It was a moment in time when you realize: this is it, this is the end, I am only 20 years of age and my life has been cut short. Our lives depended on God, on a platoon of protective troops, and luck. We had no weapons, but our bare hands and our courage to protect ourselves if the worst happened. And believe me, at that time you thought of only the worst.”

—A Nurse veteran

“I felt that the country was embarrassed by me, that the government had used and then flushed me, that my classmates condemned me, and that my family and few acquaintances were unable to understand why I didn't act normal.”

—Rev. Timothy Calhoun Sims (1949-2002)

“Survival is the reality of all war. Battlefields have no flags, only the bodies dead and wounded. High ideals have no meaning against the terror of ambush. In the final and most practical analysis, all wars are fought for the possession of dirt. Soldiers do not fight to defend god and country, but to save themselves and as many of their friends as possible.”

—Roger Melton

“The first few years in the Marine Corps were filled with a sense of confidence that bordered on arrogance. By the time I got out, there was nothing inside. Not even coldness. Leaves had more sense of direction than I did.”

—Paul Richard Wappenstein, Jr. (1944-1984)

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

About the Cover

Introduction

Memoriam

Quick Facts: Vietnam Veterans and Stress

Chapter 1 – The Molting Dream by D.L. Grigar

Chapter 2 – Poems (I)

Alone by Jim Venable

Gentle Person, Thy Concert is There by T.K.

The Junkyard by Paul Wappenstein

Old Myths by W.D. Ehrhart

Front Street by Frank Higgins

Chapter 3 – Nothing Left to Give: A Journal of Viet Nam 1969-70 by Charley Knepple

Chapter 4 – Poems (II)

Number 7 by Doug Rawlings

For Lack of A Name by Paul Wappenstein

Back Home

Memory Bomb by R. Joseph Ellis

Lorine by Larry McFadden

SSN-587 by Larry McFadden

Ask Me Not What by T.K.

With Blazing Speed the Darkness Came by T.K.

Chapter 5 – Yes Sir, Yes Sir, Three Bags Full by Don Bodey

Chapter 6 – Poems (III)

G.I. Man in Viet Nam by Sarah Bess Geibel

Rice Will Grow Again by Frank A. Cross, Jr.

Hush, hush by T.K.

Forgotten Warriors by Lonna Kimmel

Hung in Despair by Rick Ritter

Chapter 7 – The Vietnam File by Paul Wappenstein

Chapter 8 – A Personal Reflection on the War in Vietnam by Timothy Calhoun Sims

Chapter 9 – America's Uriah: The Vietnam Combat Veteran by C.D. Williamson

Chapter 10 – Masculinity and the Vietnam Vet (1982)

Bringing War Home: Vets Who Batter by Rick Ritter, MSW

An Average American

Men's Voices by Rick Ritter and Bobbie Depew

Common Problems of Veterans and Women Partners

So You're Not Sure… by Terry Springer

Chapter 11 – Wives, Children, and Other Survivors

A Message to Evergreens by Everett McKeeman

Who am I?

What Was It All For? By Connie M-W

From the Daughter of a Vet

Women's Voices by Rick Ritter and Bobbie Depew

Chapter 12 – They Never Got Used to War: Women Who Served in Vietnam

Women at War by Carol Tannehill

One Woman's Experience in Vietnam

Chapter 13 – The Vietnam Warrior: His Experience and Implications for Psychotherapy, by Stephen Howard, MD

Chapter 14 – Ideals, Death, Betrayal Are Central to PTSD Theme by Roger Melton

Chapter 15 – The War Without Mercy by Nick Rizzo

Chapter 16 – From Dakto to Detroit: Death of a Troubled Hero

Chapter 17 – Viet Nam Veterans Memorial

The Healing Wall by Karin A. Hancuff

Symbol of the Valley of the Shadow by Michael Scrogin

Chapter 18 – Viet Nam Redux: The Year of the Cock, by Nick Rizzo

Chapter 19 – Poems (IV)

All I Have by S.J.

Founding Convention Poem

Appendix A – Filmed About the Nam

Appendix B – Viet Nam in the First Half of the 20th Century

Appendix C – Vietnam Veterans Journey to Recognition by Ed Gallagher, PhD

About the Editors

Glossary

Index

Acknowledgments

An anthology such as this owes everything to its contributors. Some we can thank personally and others we can only acknowledge in spirit. Alphabetically, the contributing authors include: Don Bodey, Frank A. Cross, Jr., Bobbie Depew, R. Joseph Ellis, W.D. Ehrhart, Ed Gallagher, PhD, Sarah Elizabeth Geibel, Dennis L. Grigar, Frank Higgins, Stephen Howard MD, Lonna Kimmel, Charley Knepple, Steve Mason, Larry McFadden, Everett McKeeman, Roger Melton, Tyler Mills, Jon Nordmeyer, Doug Rawlings, Rick Ritter, Nick Rizzo, Michael Scrogin, Rev. Timothy Calhoun Sims, Terry Springer, Steve Stewart, Carol Tannehill, Jim Venable, Paul Richard Wappenstein, Jr., Candia M. Williams, PsyD., Chaplain Cephas D. Williamson, Birgit Wolz, PhD. Some additional contributors wish to remain anonymous and their works are identified only by sets of initials, but we are no less thankful for their contributions.

Several organizations helped provide reprint rights for several new articles and we wish to thank in particular the Ft. Wayne News-Sentinel, Lucy Webster (The Center for War/Peace Studies), The Christian Century, Esther Diley (Lutheran Church in America), the American Journal of Psychotherapy, and the New York Times Agency.

Bob Rich, PhD helped proof much of the new material and bring its level of quality up to meet the level of the 1st Edition text. Publisher Victor R. Volkman performed the typesetting, additional copy layout, and cover design.

A very special thank-you to the Estate of Paul Richard Wappenstein, Jr. (a.k.a. “Paul Richards”) for graciously allowing us to rekindle the flame that he ignited so many years ago.

About the Cover

Cover photo used with permission from the Stars and Stripes, a DOD publication. © 1968, 2006 Stars and Stripes. This photo of a Marine wounded at the battle of Hue was taken by John Olson. Our heartfelt thanks go to the staff at Stars and Stripes for all their help.

Introduction

One statement that has stood out since the end of the Viet Nam war is, “Viet Nam veterans don't seem to want to talk about what it was like.” Quite the contrary. Most veterans of Southeast Asia do want to talk about their experiences. Unfortunately, the majority of Americans have not wanted to listen. Most of the people in the nation spent their time trying to turn a deaf ear to the veterans, trying to forget that our country had ever been involved in such a dirty little war. There has never been anything glorious about war, including the one in Viet Nam. Wars are not made of heroes. They are not a movie in which the good guy always wins. Wars are made up of young men and women staring at the sky with vacant eyes, their life blood mixing with so much mud and slime. Wars are the broken dreams of men and women of peace. They are families being awakened in the middle of the night only to hear their young warrior is dead in some far away place with a name so strange no one can pronounce it. War is a quadriplegic amputee who has also suffered such severe brain damage that the government warehouses him in some nursing home in Midtown, USA. It is the sound of deep sobbing tearing away at some teenage girl who sees her father's name on a wall of the dead. It is the empty desire for one more hello.

The one difference between Viet Nam and all of the other wars fought by this country had nothing to do with the individual fears and courage of the men and women who fought those wars. The difference was in those who did not fight the wars. They welcomed the victors of WW II back with parades and open arms. Those who fought in Viet Nam were spit upon. They were treated as second class citizens, or, in Harrison Salisbury's words, the “new nigger.” Much of that treatment was prompted by slick Hollywood productions… productions whose only purpose were to make money. Too bad it was at the expense of men and women who wanted to do no more than what their country had asked of them. Television news also bore some of the responsibility. Viet Nam had become kind of a super soap opera, the main feature of the night. American opinion was formed against the Viet Nam veteran.

This book represents an effort by local Viet Nam veterans to speak out, to tell their side of the story. It is comprised of short stories, essays and poetry. It is the feelings of men and women who put their lives on the line, people who are, once again, trying to speak out.

Like any book, key people are involved. Two of those people are Steve Stewart and Rick Ritter. Without those two, this book would never have become a reality. Their faith and energy represent what is best about those who struggle with the problems of Viet Nam veterans today.

PAUL RICHARDS1984

In Memoriam

It was but a few months after the release of Made in America Sold in the Nam in 1984 that Paul met his untimely death. As it has been with so many over the decades of my practice many vets have survived many different “hells” only to succumb to strange and sometimes even bizarre endings in this life. I vividly remember the call from the sheriff's dispatch to be with Paul's daughter for the remaining hours during the night he died. Paul had been hit by a car while changing a flat tire in the fog early in the morning.

I'm certain I don't have the chronology correct at this point in time, but I recall the drive to his house in the early morning. His other family was farther away than could provide immediate support at that time. Thoughts and memories ran through my mind during the quiet time his daughter and I had before the dawn. It took a little while for this twist on reality to really sink in to our awareness. The many details that were looked after in the preparation for the funeral and the subsequent wake sometimes just delay this reality.

Foremost was the painful realization that Paul had survived two tours in Nam with the Marine Corps and yet still had met this early demise. Perhaps the saddest recurring theme in my 25 plus years as a therapist for vets is that many vets and their families would get closer to healing and pulling their lives back together and then the veteran's life would be ended by some strange twist of fate. It's most eerie when it happens during the first real calm point in many decades. Though of course it is a bittersweet ending…

If memory serves, Billy Joel's song “Goodnight Saigon” (from The Nylon Curtain) was a theme for many of us leaving the cemetery that day. It was a moment that struck home the pain of losing another of our brothers.

We release this second edition of Made in America, Sold in the Nam with gratitude for the permission of Lisa, one of Paul's surviving children. This new and expanded edition, about four times as large as the original, is not only a tribute to the untimely nature of Paul's demise, but also a true continuation of the primary theme of the book: the journaling of my former clients from the Vet Center during the 1980s (with a few supplements). I have continued to work with veterans from other conflicts and wars, including soldiers from other countries and former enemies as well. As such, it is clear to me that regardless rhetoric or spin, the human costs of war continue to mount in an alarming measure. We remain seemingly unable to communicate or live with our fellow travelers in this life.

Therefore, it is incumbent on us all to carry on with what we have and do the best we can to not forget—it is indeed a task that is unforgiving at times, but so very rewarding in so many other ways.

Hopefully, I have done an adequate job in editing this work anew in the eyes of Paul, Charlie, Linda, Rudy, Russ, Tommie, John, Mark, Billy, Skeet, and many others.

Rick Ritter

August 25, 2006

Quick Facts: Viet Nam Veterans and Stress

Excerpt from the Executive Summary of the major findings from the Center for Policy Research (NY) on Viet Nam era veterans1. This study was conducted under contract with the Veterans Administration and involved a sample of 1,440 men (veterans plus nonveterans).

Approximately two-thirds of all veterans worked full-time for the entirety of the time they were enrolled in educational training, in spite of the fact that the majority of veterans were full-time students.When background differences between veterans and nonveterans are statistically controlled, veterans still show some residual disadvantage in educational and occupational attainment, especially in the case of Viet Nam veterans. This leads us to conclude that military duty in Viet Nam had a negative effect upon post-military achievement. Duty elsewhere also has a statistically significant but substantially smaller impact on educational attainment.For most Viet Nam veterans, particularly those involved in heavy combat, the combat experience and the fact of survival were the most important things that happened to them during the time they spent in Viet Nam.Exposure to combat increased feelings of alienation.The main types of readjustment problems described by combat veterans are related to the trauma of combat, loss of support offered by the military milieu, lack of interest in normal activities, explosive anger, confusion, loss of confidence, recurrent memories of war in the form of nightmares.The incidence of medical problems during and immediately after military service increases with combat exposure.Although the majority of Viet Nam veterans do not believe the war had a long term negative effect on their personal development, it is clear that the impact of combat and exposure to death was profound. While the end result, such as becoming mature might be positive, many men acknowledge that pain and distress was associated with the process.Most Viet Nam veterans, especially those involved in heavy combat feel that their experiences in Viet Nam affected them profoundly.Combat veterans also report significantly more stress symptoms during the year prior to the interview. But this effect is confined mainly to veterans who served between 1968 and 1974. For this group the effect is large.Viet Nam combat veterans report more anger and hostility than their peers.The likelihood of being arrested after service was the same for men “not arrested before service” as those who “had a pre-service arrest.”In the “after-service” period, heavy combat veterans have a higher arrest rate than any group.Blacks and Latinos were more stressed than whites. Relatively speaking, simply being in Viet Nam was as stressful for blacks as being in combat was for whites.Almost 70% of black veterans who were in heavy combat are stressed today; 40% of black Viet Nam veterans are currently stressed.Men from the most stable families are likely to develop stress reaction involved in heavy combat. Men from average families are likely to develop stress reactions after exposure to even low amounts of combat. Men from the least stable families may develop stress reactions simply in response to daily life stressors. Exposure to combat does not greatly affect their level of stress reaction.Based on a case-by-case review, Viet Nam veterans differ markedly in the extent to which they have “worked through” war experiences.Most Viet Nam veterans deal with war by avoiding troubling issues, blaming the unease they feel on others, or by resigning themselves to self-pity or self-blame. Those who assume responsibility for the implications of their experiences, although a minority, set an example worth communicating to others.Reaching out to assist Viet Nam veterans may be more difficult than is often assumed. Those who are most likely to respond to offers of help frequently have problems that are more severe than many counselors and therapists may be prepared to handle. Those might be readily aided, the great majority of Viet Nam veterans with unresolved war experiences, are much less likely to accept the role of counselee or patient.

It is important for veterans to come to grips with war experiences. Programs undertaken to encourage and assist veterans in working through their experiences will not duplicate the impact of the incentives provided for higher education under the GI Bill. Working through is not an intellectual procedure and policy makers should not assume that the current GI Bill or the existing structure of higher education with its emphasis on vocational and intellectual skills will address veterans' needs for personal development.

The soldiers who carried the brunt of the battle have become the veterans who, more than most of their fellow citizens, feel the urgency of finding meaning in the sacrifices of the war years.

MARCH 1969: A week's worth of mild rain and warm winds has just about eliminated any traces of winter, but all around us tight groups of people huddle together. Perhaps they're sharing the secrets and promises that strengthen the bonds of family—I can't tell, and won't find out this time around. Mom stands nearby, torn between my nervous tension and Dad's outright impatience to have it over with. We're in Alma, Michigan, standing on the sidewalk by a squat cinder block building that houses my draft board, waiting for the busses.

When they finally arrive, twenty minutes late, Dad assumes it's time to go, so he walks up to me and pushes out his hand. I offer mine and am awed by the differences between us. He grabs me in his enormous clutch and shakes me as if to test the feel of a wrench. I don't like it but he won't let go; he's got something to say, something just for me.

“Well, good luck, and I hope they make a man out of you.” His eyes bore into me, wanting to make sure I get the point. I get it alright, and it hurts. When I turn away from him to kiss Mom goodbye there are tears in my eyes. They leave soon after, but the busses don't go for another forty minutes, so already I'm on the outside looking in.

Eighteen hours later, in a cold and crummy barracks at Ft. Knox, Kentucky, a soldier stands inches away from my face screaming at me to cut my moustache RIGHT NOW! Tired and disoriented, I start to move from instinct, and luckily move in the right direction. RUN is the command, so I run, certain now of where and what I am. It's the one-sided handshake again, and I'm on the ass end. Nothing has changed.

• • • • •

NOVEMBER 1969: Hand carrying orders for Viet Nam, I check into a camp someplace in Maryland for Combat Orientation. For the next eight days the United States Army is going to convert me from a humble clerk typist into a jungle savvied warrior. I believe from the outset that this will be a large crock of shit, and I'm right.

We get up early every day and go through the motions of warming up our bodies. If it's raining (and it was for five out of the eight days) we stay indoors and do jumping jacks in front of our bunks. Some of the older fellas with three or more stripes on their arms seem disinterested by the warm-up sessions, more often than not they skip this part to go take a dump or clean up. I've noticed a lot of bars on this base, and the bedcheck at night is basically nonexistent, for obvious reasons.

By the end of the second day I've borrowed an E-6's shirt and am digging the nightlife in a lively club a few blocks away from our barracks. He's been through one tour already, and is taking the Orientation again just for the hell of it. A career man, he tells me that combat duty is a piece of cake compared to the spit and polish garbage of Europe or the States. He goes on to assure me that my coke bottle glasses will keep me out of the boondocks, so what's to worry? We have a few more beers and I leave, feeling no pain.

Outside a cold November fog shrouds the night, creating an ideal backdrop for one of the most bizarre scenes I've ever witnessed. From nowhere a bugle call pierces the silence around me, and seconds later the barracks to my front left erupts with activity.

From both stories of the building, men scramble out into the muddy street and form two perfect lines. They are dressed to the max: white belts and gloves, shiny parade helmets, jackets and pants with lots of red decorations, boots glistening with the familiar spit shine I've never perfected. This is a showboat outfit, and from the intense precision of their lineup I gather there's a show about to begin. Easing back into the cover of fog I watch and wait.

Long minutes pass, I light a cigarette and wonder if this is a waste of time. Those dudes are classy though, not a whisper, cough, or movement from anyone. A vision flashes through my mind—I once owned a set of plastic soldiers and used to line them up in formation then leave them somewhere to go off and be a kid again. Except for little puffs of hot breath, these guys could be that set of plastic soldiers, left behind and waiting for the commander to come back. A barracks door slams behind them, and suddenly the Man appears.

Wearing the standard military green uniform, I would never have guessed that he was the reason behind this show, but it's immediately obvious that God comes in many disguises. From the second he is in view of this formation every head turns to watch his movements. It's like he has forty strings tied from his body to their heads, 'cause no matter where he is, their eyes are on him. With the memory of basic training still painfully fresh, I realize that these guys are in a whole lot of trouble.

He paces the length of his formation but never looks at any of the men. When he finally talks his voice sounds tired, not the crack-your-ass bark of a basic training D.I., but there's enough poison in his words to make my ass pucker.

“You have disappointed me again, and now you're gonna pay. After this little exercise tonight I intend to let you settle the problem that's ruining your chances to be officers in the United States Army. At oh-seven hundred hours tomorrow morning some of you will report to my office for reassignment. I don't care what you look like when you get there, I don't care if you have to be carried there, but the problem IS going to be solved tonight. At oh-eight hundred hours there'll be a full dress inspection, and anyone who fails to make the grade will also be reassigned. Begin!”

The front line does a left face and moves with inhuman precision until there is only one line facing the man. Without a word they all turn face right, then the lead man double times it up to the front of their barracks, lays down on and starts to crawl around the building. Another man is right behind him, and in less than a minute the whole formation has formed a human snake wallowing in the cold slime.

I don't like watching people suffer so I try to slide by the Man and get to my bunk, but he spots me and asks for a light. I've got one, but hate like hell to share it with him.

“You here for the orientation?” he wants to know. I say I am and he laughs. “Just think, you might have one of these turds for your C.O.”

On the last day of our training program we are taken out for a “combat simulation,” complete with full backpacks and empty M14 rifles. Loaded into the back of an open truck, we travel to a scrawny wooded area and are told to pile out and patrol the place. Less than halfway into the patrol we get ambushed. Moving around like cattle we bang into each other, dive for the same cover and fall on our weapons. I trip over no fewer than four personnel mines and am shot repeatedly by the enemy.

Riding back in the truck we smoke cigarettes and bitch about having to clean up the rifles before receiving our diplomas in combat training. I look around me and see a lot of men covered with red powder. The red powder came from those personnel mines that explode like party favors under our feet. It seems to me that if the redness were blood from our bodies then no one would be laughing, and I don't think I'm ready for the war.

• • • • •

JANUARY 1970: Viet Nam smells like a garbage dump, has too many rows of barbed wire, and the Army doesn't seem to know what the hell it's doing. I arrive in country at an enormous airfield, am flown to an unnamed place and dumped in front of a corrugated metal building. No one is there to meet me, and my name isn't on anybody's roster. The men who have landed with me leave in jeeps or trucks, but I can't go with them because my name isn't on the list. When the last jeep starts its engine, I panic and jump in. The soldier laughs, says he'll take me to his camp and see if the C.O. can find a spare bunk for the night. I don't give a damn if I have to lay on the floor, just don't leave alone.

The C.O. says it's no problem; I can stay until my orders are straightened out, go find an empty bunk and relax. I find an empty bunk, lay down, but can't begin to relax. When we drove through a little village to get here I saw a lot of Vietnamese people, and they looked at us with hungry eyes. I saw tiny houses made out of coke cans that had been cut open, flattened out and somehow put together to form walls. I saw miles of barbed wire and soldiers patrolling the perimeter of this camp with vicious police dogs by their sides. This is a dangerous place, and I can't relax.

The night is dark and thick and still. It's hot, there's a rat hole in the latrine, and the mosquitoes are out in force. I'm out of cigarettes but there's no place to get any. I lay on a mattress that smells like piss in a roomful of empty bunks and sweat from heat and the fear of being killed in my sleep. Hours later I'm jarred awake by an explosion that shakes the earth. With no weapon, no orders and no friends, I crawl under my bunk and eat dust. There's lots of shouting and some machine gun fire, but it doesn't last long. I need to relieve my bladder so bad it makes me shiver, but I wait another minute or two before making the charge.

Hungry for news and some nicotine I leave the barracks to snoop around. Someone spots me not wearing a helmet or flak jacket and chews on my ass, but I bum a smoke anyway and he catches the scent of a “newbie.”

“How long you been in country, dude?”

“About five hours. I don't like it.”

“No shit Sherlock. Are you stationed here?”

“I don't know, I don't think so, but I really don't know.”

“Well if you don't know then chances are you're not. It ain't likely they'd put ya here without a rifle or a helmet for Christ's sake! You better get back to your hooch 'fore the brass spots ya.”

“What happened just now? Were we attacked?”

“Sorta,” he drawls, enjoying my anxiety. “That was a rocket, knocked out a bunker, hit it dead center. Some guys musta been in there tokin' up, they're dead, but we don't know how many yet. I'm s'posed to be over there now hunting for body parts. You get yer ass back in the barracks and put a coupla mattresses on the top bunk. Mattresses help stop the shrapnel. Here,” he throws me his pack of smokes, “you look like you're gonna need these tonight.”

I do what he tells me, then sit in bed and smoke the rest of the cigarettes. There aren't enough of them to get me into daylight hours, but I'm not very tired anyway, so I listen to the night around me and kill mosquitoes. I think about men dying in a bunker while smoking dope, and wonder how long it will be before I get to taste the famed Nam weed. I've heard that it's some of the world's best and if tonight is any indication of the year ahead then I think I'd rather die stoned than straight .

• • • • •

After two days of waiting I am taken along in a heavily armed convoy to Saigon for reassignment. This is a no nonsense trip that reminds me of all the opportunities I had to skip across the border and go Canadian. It's hot and muggy, but I've been ordered to wear a helmet and flak jacket or pay the consequences. Beyond and behind us are jeeps with 50 caliber machine guns mounted in the backs, there are helicopters overhead and men with rifles and grenade launchers in every vehicle. Nobody's laughing at anything or anyone, the real war is all around us, and I still don't have a weapon.

We roll past man made craters in the earth, buildings that are sandbagged so heavily you can't tell what they're hiding. Twisted, charred heaps of vehicles that have been pushed off the road. The whole damn trip I never see a stretch of road that isn't barricaded on either side by barbed wire, and I wonder where the hell I'd run to if we were hit.

Saigon is one of the filthiest and most exotic cities in the world. Gigantic pagodas stand beside modern ten story buildings, the traffic patterns are impossible to decipher, and there are literally thousands of people riding around on tiny motorcycles, bicycles, and dinky little vans. American and Vietnamese troops are everywhere, so is barbed wire and the smell of rotting garbage. We leave the convoy and proceed to an old hotel in the heart of the city. Right beside the hotel is a garbage dump, and if my stomach weren't empty I'd barf at the smell of that monstrous shit pile.

The hotel walls sweat, the lobby carpeting is moldy, and there are lizards skittering around on the walls. I'm given a room number, told not to leave the building, and left to my own devices. The room has nine foot ceilings and a paddle fan that doesn't work. The windows are open but I'm not overlooking the garbage dump, thank God! Instead, I'm overlooking the street, and it never stops being busy. At night I hear women scream, gunfire, sirens and outraged cries of men beating men. There are Reader's Digest magazines from the early Sixties lying around, and eventually I read a dozen of them. Time has no significance, I eat, shower, read pulp or watch the workings of an alien world from my fourth story window, and sleep. It seems like I should be taking lessons in the Vietnamese language or learning more about the culture or any damn thing, but I wait, another object left to rot in the relentless heat.

Five days of smelling and hearing the cesspool of Saigon makes my orders for assignment seem like a message from heaven. I don't give a damn where I go as long as I can call the pieces of ground I'm standing on my space. The days of being nowhere and nothing to anyone have already gnawed a hole in my soul—I need a spot to stand on and defend. That spot is called Nha Trang, and I'm told it's a beautiful coastal city with a fairly secure military base.

• • • • •

FEBRUARY 1970: Camp McDermitt is both clean and fairly secure, but I don't know anything about Nha Trang because it's off limits. The South China Sea is close enough to hear and smell, and there's a beach where we can swim on off days. I share a small hooch with some dude from the motorpool who drinks too much but likes Big Ten college sports, so we get along alright. I've been issued an M14 plus flak jacket and helmet, but they won't let me sight my rifle in. That bothers me, but I don't tell them about it because they wouldn't give a damn anyway. The order that prevails is don't make waves and you won't be noticed. I've been assigned to Headquarters as their clerk typist and go-fer, am now receiving mail from home, and feel as though I'm gonna be OK.

We've had four rocket attacks in four weeks, the largest one being a seven round barrage that kills three men in another company and destroys two bunkers. Rumor has it direct hits are few and far between, but the piercing shriek that gives us a second's worth of warning never fails to wrench my guts. With mountain ranges on three sides of our camp it's impossible to control or prepare for these random attacks, so I learn to live with one ear tuned to the skies.

The night hours are deceptively quiet and peaceful. There are a lot of hooches with big Japanese stereos, but everyone has headphones and usually keeps the noise down. I wonder how someone with headphones can tell when there's an attack, but don't bother asking, it's live and let live around here, no doubt I'll figure it out later. What I'm most anxious to figure out is where the dope comes from. I can smell it, can hear the results of it in laughter that fades when I step outdoors to look at the night sky, but nobody's offered to initiate me yet, so I listen and wait and hope for acceptance.

Six days a week a couple hundred Vietnamese pass through the front guard post of the camp and become barracks, kitchen, and bar help. Our barracks is maintained by two tiny women, one so old and grizzled I wonder how she keeps moving, the other a pretty young flirt with a taste for American possessions. At the cost of forty dollars per month per man they make bunks, sweep floors, do our laundry and even shine our boots. By Vietnamese standards of living these women are high paid and extremely privileged personnel. I try and try to get them to teach me Vietnamese and tell me about their homes but they won't do it, they say Americans come and go so often there's no reason to waste time learning anything. I think it ridiculous that I can't speak the native tongue or at least understand it enough to ask for simple directions. How the hell can we be good allies if we can't understand each other?

One night Don pops his head into our hooch and tells me it's time to go out for a drive. I follow him to a covered pickup truck and jump in the back, excited by the prospect of sinning. We move a short distance, head out of the camp and into an area that can't be more than three hundred yards off the base. The truck drives behind a small hut then stops to unload about ten of us. I follow the crowd through a wrought iron gate that opens into an enclosed garden setting, and we are met by a group of women. Some of the women giggle and point to familiar faces, others hide beneath wide, cone-shaped straw hats, indifferent to the next pairing. An older woman appears to greet us formally, then collects five dollars per man and disappears as quietly as she came. It's open season now, but I'm new to the meat market game so I hang back and watch.

Though I don't say so it's not a woman I want, it's a taste of the weed. In a minute or two there's no one standing in the garden anymore except for me, and I wonder how I can get what I'm after. Mama-san comes back and spots me, so she walks over and asks me if I'd rather have a boy instead of a woman. Shocked and embarrassed I shake my head no, so she barks out a command and a woman in a cone hat appears. Taking my hand, she leads me through the garden and into a tiny room. One candle on a small table illuminates a cot, a chair and four dirty gray walls. No pictures, no mat on the dirt floor, no incense to disguise the smell of stale semen and sweat, this is a working class shelter, and my name is Joe.

I don't want this, I don't want it at all, so I light a cigarette and remain standing. She sits down on the narrow cot, takes off her hat and looks up at me, waiting. I can't tell her age, but from the calluses on her palm I guess she's used to farming, so I try to talk about farming. I ask her about the rice but she doesn't speak much American, so that goes nowhere in a hurry. She wants me to sit down beside her so I do, then let her take my arm and put it around her waist. She puts her hand on my leg, strokes my thigh a couple of times then waits for me to respond. I'm waiting too, waiting for an emotion I can't seem to remember.

I touch her hair, looking for a place to start. She sort of leans over my shoulder, perhaps grateful for some tenderness, but when I try to kiss her she turns her head away, so we're lost again, lost and desperately divided. She won't let it go though, pulling me down to lie beside her on the cot, determined to get through the act, or at least go through the motions. Despite a sense of helpless confusion I'm warmed by the length of another body near mine. Moving quickly, she lifts her feet up and separates my legs, then rubs my crotch with enough pressure to achieve the desired effect. Before I can respond though she stands up, turns her back to me and starts to undress.

Following suite, I get my boots off by the time she's undressed and hidden beneath a sheet. I didn't even notice a sheet on the bed, but seeing her peek over the thin pale cloth stimulates my hands to activity. Moments later we're lying side by side. She's slipped one hand around my waist and is urging me over, but I want to touch her first, to feel the length of smooth brown skin under my hands. I'm hard now, and it's starting to feel like something familiar, but my hand moves across her stomach and freezes in shock. Ripping the sheet back I look at her, look long and hard, and see that she is well into pregnancy.

It's wrong, it's all so fucking wrong I don't want anything to do with her, but when I jump up and grab my pants she grabs them too and tries to pull me back into bed. She cries out, still pulling on my pants, and before I can yank them out of her hands, Mamasan pulls the blanket door to one side and asks me if anything is wrong.

I'm naked and so goddamn vulnerable I don't know what to do. Without waiting for an answer, Mamasan snaps a line of abuse at the woman in the bed that sends her shuddering back under the covers. She shakes her head no no no, huddling in terror against Mamasan's attack, and suddenly I'm saying that everything's just fine, go away and leave us in peace. I rip the blanket out of her hand and slap it shut, but I'm shaking so bad I can hardly light a cigarette.

Sitting on the edge of the bed I offer her a puff, and she accepts it. We smoke in peace, then she puts her hand on my shoulder to pull me down and I fall. Lying beside her, I wonder what her husband thinks about her second job, but there's no use in asking because we don't speak the same language. She wants me to roll over and move with her, but I know it won't work. Whether or not it works doesn't matter though, she's insistent that we go through the motions, and when I lay on her, she finds enough skin to breach the sacred hollow.

I'm too heavy, she pushes me off her stomach, but I'm supposed to keep moving too, so I pull myself up and make our crotches rub. We rub for awhile, two damp sticks of wood having a dull go at the process of making fire, then I sigh and get up to put my pants on. In very broken English she asks me for three dollars. The five dollars I gave Mamasan was for the room, not the pleasure of this woman's company. Without looking to see what I've got I pull out a handful of bills and place them on the bed. She grabs them and starts counting the money, but I turn away and don't look at her again. Scrambling to get dressed, I finally leave the room to go outside and put my boots on. It's hot and still and the air is cramped with humidity, but at least I can see the stars and hope that somewhere something is going right for someone.

Later that night, a long time after taking the longest cold shower of my life, I lay in my bed and feel like scum.

• • • • •

MARCH 29th, 1970 – EASTER SUNDAY: Just another workday by military standards, the C.O. issues orders that any man who wants to may be excused for an hour to go to church services. I thought about it but there's no fan and some asshole vandalized the air conditioner for parts. I don't bother to ask myself if anything is sacred anymore, and I don't go to the Sunday service either.

Around eleven o'clock there's a high piercing scream in the air and I hit the deck crawling. Apparently everyone around me does the same 'cause the ensuing shrapnel that tears through our West wall misses flesh. Three more drop around us in rapid succession, none of them as close as the first but still in our company area. There are shouts and the sound of boots scrambling over gravel, so I grab my flak jacket, helmet and the company radio and dash outside to the command bunker. Two of the five posts respond, we've taken a hit across the road, no sign of casualties yet, but where the hell are posts 1, 3, and 4?

More rounds drop in, another one smashes into the buildings across the road but I'm in contact with 1 through 3 now so at least we've got eyes to see. Number 2 says it's an affirmative on the hits in our buildings, but he doesn't see… yes he does, a man has walked out into the driveway, away from cover of the buildings. He looks wobbly, better send someone out there quick to pull his ass back.

I tell the First Sergeant we've got a wanderer, maybe shell shocked, and Top wants to know if I'll go out and get him. I hand Top the radio and start running. It's only about thirty yards away but before I'm half way there someone's already with him. Why the hell don't they go for cover?

Another round slams down about fifty yards to my left side, close enough to shower my low crawling ass with gravel, near enough to send me back towards the command bunker. We wait then for about five minutes but it's over, the damage is done. With everyone still on red alert, I hustle across the road to get an official word on our wanderer. The official word is that he's full of tiny shrapnel holes and no longer breathing. An ambulance hits the scene with sirens screaming but we hardly notice them, caught by the aura of fresh death. The ambulance is gone in less than a minute, and there's nothing else to do but go back to Headquarters and report a K.I.A.

I don't remember very much about the rest of Easter Sunday. Throughout the Christian world this is one of the most sacred holidays, a time to celebrate rejuvenation and the hopes of eternal redemption. Apparently nobody told Charlie Cong that this day is a good one to lay all weapons down and rest in peace 'cause he threw enough shit at us to take one away.

The Mess Hall's outdone themselves in preparing a fine Easter dinner but half the company don't even show up to eat. Men trickle in and out of H.Q. to pick up the news and it's plain to see that a haunted mood prevails. Late in the afternoon a well liked E-6 drops by, sits down and bums a smoke off me. I know he doesn't usually smoke so he must be in to talk awhile. Turns out he was the last one to see our man alive and well. Minutes before the rocket attack he'd stopped in to see if everything was OK and the dude told him he'd just received orders to leave country.

I listen but don't talk, not sure if I can keep from breaking down. As a teenager I shot two deer for food and still remember the brutality of my act against such beautiful animals. Hearing Bob talk about a man dying with two weeks left in county reminds me of those deer. Even with holes in their bodies they still ran for the woods, giving their blood to the snow in the hopes of reaching cover. From the depths of my heart comes a terrifying question: In the act of dying did that man leave his building with thoughts of walking home?

ALONE

The womb behind, the cord cut;Lying in a basket… alone.Small child, parents cannot understand,Though they reach out… alone.Thru the learning years, not grasping those around,Reaches adolescence… alone.Facing puberty, deepened feelings and new drives;Questions afraid of the asking… alone.Military years, prime of youth;Cannot fit into their molds… alone.Sees the beauty of life, the gifts of God,Feels no lust for the world's ways… alone.Longing for a family, fails in marriage,Frustration, caring locked deep in the soul is not freed… alone.Cries out, agonizes in the hurt,Revels in the pleasures of life so many miss… alone.The truth, communication lies in the music;Wailing of blues, driving riffs of rock, classical serenity… alone.If only someone knew, is there no way of finding;Deepest feelings of love cannot be shared alone.

JIM VENABLE

August 31, 1981

GENTLE PERSON, THY CONCERT IS THERE

Gentle person thy concert is there Who took your brothers life?Music was made by men who know How best to write the notesA shot, a shell a burst and sound Whistle the song of deathThe chorus is sung by men who never Could carry a tune beforeConductors appear to lead the parade But only from afarLest they be touched with the notes of the song That they themselves have wrote.

T.K.

THE JUNKYARD

I remember a child only six years old not really helpless just hungry and bold.

We drove by the junkyardHe took out his tin cup dipped it in swill drank from it quickly as if it could kill

We came to a stop in our traveling jeep he hollered from behind us “Hey G.I. anything for me to keep?”

He had no parents they had been killed his value for life was deeply instilled.

I tossed off some C-rations said, “this surely will beat anything so far you might have had to eat.”

He looked at me kindly then said, “cam on ong. for my brothers and sisters I will take this on home. “

We drove down the road when out loud I had said “war is worse for the living than ever could be for the dead.”

PAUL WAPPENSTEIN

OLD MYTHS

Citations, medals, warrants of promotion:

All the things I ever earned I framedAnd tacked up in an attic roomI used to use for studying.

That was several years ago;Before the nightmare eyes had fully set,Before events began to showHow deeply they were etched.

Now the room is cluttered with old clothesAnd broken toys and boxes.I don't go up there anymore;I've lived the myth,and seen the horror of the lie.

Yet even now, sometimes I findFaint traces of an older pride.

I guess old myths die hard.

W. D. EHRHART

FRONT STREET

His distrust of trees came in the warhe said, every night watching.looking them over before bedding down.Birds deceived by searchlightsperked up, sang songsin dust covered branches.

Couldn't walk in the openor under treesbecause of snipers, andeven now refuses the sidewalkthat busy elms have madeinto a tunnel on Front Street,refuses except when walkinghis four year old daughterto the far corner and back,returning always with a blotof wetness on his pantsand the squealings of a child –her hand held too tight too tight daddy.

FRANK HIGGINS

“I will never romanticize war,War is hell.”

Readjustment Blues

Every vet thinks that once they get off that Freedom Bird that they can start living where they left off. So many things change while you're gone; friends move away, get married, and are busy holding down jobs, and the same goes for family. The first thing a Vet feels is separation and isolation.

Home had been my anchor. During those eleven plus months while I was 10,000 miles away, the world seemed sometimes unreal. The only contact was through unsatisfying letters, which could only hint at the changes taking place there. The military's programmed de-personalization had unleashed so unreal of a state of mind in me that I could not detect the changes in my identity. Identity, or lack of it, was only part of the problem.

The Vet vows that once home, he will never think of the Nam again, but the first newscast you see with footage of Nam grunts will take you right back. And when the radio played The Doors, Eric Clapton, Johnny Winter (etc. ad infinitum) I could practically feel the lumps of the sandbag bunker. All those lonely nights on the bunker listening to the radio was conditioning, and I could not get away from the stimuli.

Some fears creep in, ambush, and harass you. When lightning hit a flagpole one night, I responded by dressing myself and running out of the room completely confused about what had happened. Was I merely animal instinct? In a later incident, I was attending night school while there was some demolition going on nearby. With the first explosions, I wanted to tear myself out of my seat and run outside. I don't know how, but I resisted. I was gripping the desk with white knuckles and feeling very anxious and uncomfortable. When I looked up, I realized that the professor and several students were looking at me. I let it pass without comment. How could I explain, and how could they understand?

At the end of the first year back home, I had not gone a day without thinking about Viet Nam. I wasn't concerned about this except that I also talked about Nam a lot and sometimes people would say, “Well, that's over now.” But when I was there I wanted to be home, and when I got home I sometimes wanted to be there.

Another year passed and I was involved in getting married and finishing school, but I still thought about the Nam a lot and talked about it less. This journal is the first time I have been willing to express some of the feelings I have held inside since my return from Nam.

About that time, the news was filled with Viet Nam as the NVA took over Quang Tri province and headed south. Eventually, Saigon fell. I knew it was coming, but I was shocked—stunned—by the pictures of that last helicopter lifting off the American embassy building. News photos had shown Russian-built tanks on the road through QTCB.