Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IMM Lifestyle Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

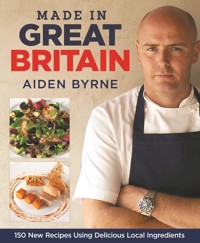

Rising star Aiden Byrne shares his passion for great British cooking. The youngest chef ever to win a Michelin star, Aiden is now head chef at the grill in London's prestigious Dorchester hotel. There are 150 recipes divided into four chapters: Vegetables, Fish, Meat and Desserts. Ranging from beautifully simple dishes to the more fabulous creations, all the recipes showcase Aiden's talent for creating perfectly judged dishes using the best that Britain has to offer, from Scallops with Garlic and Lime Puree to Veal Cutlets with Broad Beans and Girolle Mushrooms and Warm Chestnut Cake with Chocolate Sorbet. As well as the recipes, Aiden writes authoritatively on a number of food issues and the book includes black and white photographs of Aiden visiting suppliers, sourcing ingredients and at work in the kitchen. More than just a recipe book, Made in Great Britain is a celebration of British food as well as a fascinating look at the motivation, passion and attitude of an emerging talent.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MADE IN GREAT BRITAIN

Aiden Byrne

CONTENTS

Foreword by Tom Aikens

Introduction

Vegetables

Fish

Meat

Desserts

Index

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD BY TOM AIKENS

Where do I start? Aiden and I have known each other for well over ten years now, working together for about four of those. We’ve been through a lot together and have had some great times – Aiden is one of the closest friends I have as a chef. We have shared and talked about everything to do with food and it is this understanding of and passion for food that has brought us together. It has shaped his life and made him the great chef that he is today.

It all started when Aiden came to work with me at Pied à Terre back in 1996. I will admit that at that time I was a very, very demanding chef that worked all my staff extremely hard. I would stop at nothing to get the best from them and worked them harder than I really should have. But Aiden just kept on going and never stopped or wilted under the extreme pressure of working beside me. He was my number two and he just would not stop till the job was done the exact way that I had asked and wanted from him – with never a word of complaint. He would come with me to Covent Garden vegetable market at 3.30am, then we would go straight into work for 6am, pack everything away and then do a full day’s work till 1am. We were working six days a week then – myself, Aiden and three other chefs in the kitchen for almost nine months. It was unbelievable that we ran that kitchen with just four or five chefs. This is where he helped me keep the two stars at Pied à Terre and without him there I realise that this could and would have been an impossibility. I am truly indebted to Aiden and what he did with me back then.

He came to work with me again as my head chef at Tom Aikens for a further two years and here I really pushed him to his limits. He knew what I wanted and what we had to do; I could not have asked any more from a person. When I think back I was the luckiest man alive to have Aiden with me, and I don’t think he has realised – even today – how much I value all that he did. The pressure I put him under and the stress of the work never fazed him, tough scouser that he is. The man would never buckle, but just get stuck in and push on. He understood the reasons why we did these crazy hours and why we worked so hard. We both share an old-fashioned belief that with hard work and determination anything is possible. To have someone like him as your right-hand man is priceless. He worked without question and with total dedication.

Running a kitchen is about forming relationships with your team and fellow workers, but especially with your number two. It can be very difficult trying to combine a working relationship with a friendship as you have to keep the balance between serious work and light-hearted kitchen banter. I know that there were times when I demanded too much from Aiden but he never complained. He was always the first one in and the last one out.

You may all wonder what drives us crazy chefs to work the hours we do but with Aiden it genuinely is a passion for excellence. I believe this makes him stand out from a lot of other chefs. Working under huge amounts of pressure gives you standards, procedures, schooling, dedication and understanding. I relied on Aiden more than anyone else. Every place you go to work you take something with you, be it the way the chef works, the style of food or the way the kitchen is run. Eventually you find your way, your style and your food. With the understanding of all this you will make your mark and Aiden has certainly done this. It makes me very proud to see how far he has come and to see him challenging himself and his team in such a positive way. We can all take the easy routes in life and we can all follow other people but to be a leader and to stand on your own two feet takes a huge amount of effort and hard work.

Aiden has come full circle in his career and he now has chefs looking up to him and coming to work in his kitchen because of him, his food, his style, his personality and his own drive and dedication. I will never forget the times we have had and shared together. There were great times and hard times but it was the way we worked together, the way he made it all worthwhile and how he motivated my staff that I thank him for. I have a lot of great memories and sometimes I do get nostalgic for the old days when we did service together and could practically read each others minds. I miss that and if ever the opportunity came along again for us to work together then I would jump at the chance. There has never been anyone else like him, but I will always have his friendship and that’s invaluable.

INTRODUCTION

British food has for a long time had a pretty bad press, unfairly, in my opinion. But it does, in fact, have an extremely rich and varied history that stretches right back to Roman times. And there is so much fantastic produce that is available to us in Britain. True, British food and cooking has had its low points but many people today are beginning to rediscover good food and recognise that it is at its most tasty and healthy when fresh and in season. In towns and cities across Britain, farmers’ markets, selling produce grown or made locally, have become increasingly popular. What’s great about these markets is that you can talk to the producer while he or she wraps up your purchases. All this has been accompanied by a rekindled interest in cooking and a backward glance at old family favourites.

In this book I have attempted to show you how the best British ingredients can still be combined to create an outstanding British cuisine that rivals the best in the world. British cuisine has really come a long way in the last few years but in London the change has been remarkable. London has long been a dynamic centre of food fashion and there are now hundreds of fantastic restaurants – many of them serving world-class food.

Today, there is no reason why good British cooking can’t be the rule, rather than the exception – and not just in London’s fashionable restaurants. I’d like to see great British food in restaurants right across the country – and more importantly, in people’s homes and kitchens.

Today’s British food scene

When I was a young chef, things were very different as far as produce was concerned. It arrived at the door, we opened the packaging and did what we needed to do to it: seasoned, marinated, cooked it and made it look pretty on the plate – at least that was my understanding. The main priority was to make the customers smile, leave happy and tell their friends. Then the restaurant would stay busy and I’d keep my job.

Now, almost 15 years on, things have changed dramatically. I have, I hope, a little more knowledge and a lot more respect; respect for the clientele, respect for my staff and most importantly respect for the produce.

If I were to have written this book ten years ago, it would have been destined for the professional chef, but now, that is not the case. Times have changed. Cookery books like this have replaced designer magazines and autobiographies as a coffee table staple. As a chef that is an amazing change to witness and be a part of.

Actually, ten years ago I would not be able to write this book unless I had three Michelin stars and a chain of restaurants to my name. People are now looking for more variety, are keen to try new ideas. They want to push their culinary boundaries – not just by what they eat in restaurants but in their homes. Knowledge and information are key and that information is in demand more and more.

The work that has taken place to change the stigma of British food is slowly paying off. We are well on our way to being respected around the world. Back when I started out, top restaurants were the only ones championing traceability of produce, and as time has gone on this approach has filtered down to gastro pubs, farmers’ markets and even the big supermarkets.

Fantastic produce is now available to everyone. You just need to invest time in shopping around. We can all be a little lazy and just accept what is placed on the supermarket shelf irrespective of what is in season, what is local, what is British. Perhaps our supermarkets don’t want their customers to think seasonally, because they believe seasonality is not profitable?

Luckily for chefs – and those of you who cook for pleasure at home – we have farmers’ markets, family-run butchers, fishmongers, cheese shops and an endless list of specialist suppliers to choose from.

There are still plenty of small producers in this country dedicated to the art of cultivating the very best varieties of seasonal, British produce. These fruits, cheeses, meats, and vegetables have not been genetically improved for the sake of shelf life, nor inoculated for long-distance travel. Food bought in this way represents only a small handful of all that we buy. We must all continue to make an effort to change and as long as we keep chipping away there is still hope. Perhaps one day one supermarket will dare to be different and find a way to sell seasonal British produce and still make the huge profit their share-holders demand. Let’s hope so.

The making of a chef

I always knew that cooking at this level was going to be hard, but never this hard. Once I started cooking everybody told me I was mad. Why do you work so many hours for such little money? Why do you put up with all the abuse? I didn’t have the answers because I didn’t understand it myself. Still to this date I don’t recall the day when it went from obsession and adrenalin to actually being my career, something that was going to provide for my family and make me feel important and worthy of something.

I feel extremely lucky that when I was just 14 years old I found my vocation, my passion, my life. I owe a lot of my determination to my dear cousin and friend Alan Feeney. I suppose he was like my big brother, he chose catering in school and I copied him and that was it, there was no turning back.

At catering school, I got a real taste of what was going on in the outside world. At weekends and public holidays I used to travel to Wilmslow in Cheshire and work for free in a hotel called Stanneylands. Iain Donald was the executive chef. He both frightened and excited me. He was mad. He spoke fluent French in a very strong Scottish accent and grown men were obeying every order that he shouted. The service ran like clockwork. It was here that I thought, ‘This is where I want be’. Fifteen years on and my brother Louis, who is also a chef, now works for Iain Donald.

So college finished and off I went to the big smoke. I hated every minute of my first short visit and vowed never to go back. I didn’t learn a thing; it took the wind out of my sails. I hated my job and my world was shattered.

I came home and headed to the Chester Grosvenor hotel. I heard it had a Michelin star; the Arkle restaurant was impossible to get into, so I worked for free until a position became available. Here I started to learn how to respect ingredients, how to cook vegetables properly, how to be organised and efficient.

I stayed here for 18 months and learned as much as I could until I heard of another Michelin starred restaurant not too far away, called Pool Court Restaurant in Otley (West Yorkshire). Here I learned how to taste; the senior chefs would ask me to taste their food to see if it was seasoned properly – I now insist all my chefs continuously taste what they are cooking. It was here that I met my best friend Roger Hickman. We went through everything together: the head chef used to make us cry on a daily basis. I guess that was his way of getting the best out of people, by filling them with fear, but it’s a tactic I disagreed with then and one I disagree with now. A pat on the back or a ‘well done lad’ will stay with someone that young and naive for a very long time. I remember him whispering in my ear ‘I was better than you when I was 20’, but I was to have the last laugh.

The way I treat my staff now is very important to me, mainly because of the way I was treated for all those years. My chefs work four days on and three days off. Of course they put in a full week’s work for the four days but at least they can experience a life outside the kitchen. They receive credit where credit is due and a detailed explanation when they have made a mistake.

After Pool Court I packed my bags and off I went again on my travels, avoiding London like the plague. I ended up in Norwich, in a small family restaurant called Adlard’s. To say I was wet behind the ears is an understatement. I didn’t understand why mousses were splitting, why my anglaise was lumpy. I had never cooked a piece of meat before. With what little money I had, I bought cookery books by Harold McGee, Raymond Blanc and Marco Pierre White. These are what spurred me on and I loved it. I had my own little domain.

I think other than David, the chef/proprietor, I was the only one who had worked in a Michelin starred restaurant. David was trying to bring up two very young children at the time, and when he was not in the kitchen the standards plummeted. One day I told him he needed to employ a sous chef; he gave me the responsibility and I ran with it. I went into work on Monday mornings and came out on Sunday mornings. I had no life, no friends, and no money. I put into practice what I had learnt from previous Michelin starred restaurants and studied my cookery books.

After about nine months, David received a phone call from a journalist friend to say congratulations, ‘for what?’ said David. ‘For getting your lost Michelin star back’. Ours was the first restaurant in the country to have done this at the time. And I was the head chef! I didn’t really understand the importance of this until I went to the Michelin dinner at the Savoy hotel.

I had to wear a dinner suit; I had never even worn a suit before let alone a dinner suit. It got even more bizarre for me when I arrived for dinner. Standing in front of me were John Burton Race, Raymond Blanc and Brian Turner to name but a few. My chin was on the floor. I kept pinching myself, ‘can this be true?’ All my idols, the authors of all these books, all in one room and I’m here receiving a Michelin star for Adlard’s.

I stayed with David Adlard for 5 years, but I needed to learn more, so I bit the bullet and went back to London. But I am eternally grateful to David for giving me that first opportunity.

I set up camp next with Richard Neat who was the head chef of Pied à Terre in London, which had two Michelin stars. The kitchen was a dungeon, literally. It was a million miles away from my safe little domain in Norwich, everyone wanted to be the best, no matter what it took. I lasted six months and committed the ultimate cardinal sin. I bolted.

Then Tom Aikens took over as head chef and I was encouraged to come back. Never have I met one person who has so much drive and ambition. Tom, without a shadow of doubt, has been the biggest influence on my career. We have stayed strong friends through thick and thin. It is difficult to say how I feel about Tom; he still makes me nervous but at the same time I couldn’t imagine my life if Tom hadn’t come into it.

Soon it was time to move on again, and after five years in Dublin at The Commons restaurant (where I picked up another Michelin star), I was called by Tom Aikens to return to his eponymous restaurant as his head chef. Even though I was now 30 years old, with a wealth of experience behind me and two separate Michelin star awards, I can honestly say that this was the hardest period of my career. Tom pushed me to the limits but I always saw the value in what he was doing. I knew that by going back I was taking one step back to jump two steps forward.

My arrival at The Dorchester in London in 2006 as head chef was an enormous privilege and I achieved so much with the help and support of an immensely talented and dedicated team of chefs. The facilities were incredible and enabled me to grow, distil and concentrate my ideas further as a chef.

In 2009 I had an amazing opportunity to take the next big step and become the chef/proprietor of The Church Green in Lymm, Cheshire. I could see it was a pub with masses of potential but it was turning out the kind of pub food that no-one should have to eat – freezer-to-microwave meals and greasy chips with everything. It was a big task but the main priority was getting the business up and running. The kitchen has had a complete refit, I’ve established a kitchen garden and obviously created some fantastic new dishes for both the pub food menu and the fine dining menu. The food is still British but simpler than the Dorchester fare and the focus, as ever, is on locally sourced, seasonal produce. I still insist of the best quality ingredients, whether I’m cooking Fish and Chips or Roasted Sea Bass with Crab, Basil Gnocchi and Tomato Confit.

Cooking at home

I consider myself extremely lucky because not only is cooking my passion but it is also my job – it’s what I get to do every day. Running a professional kitchen means that I have access to some of the best ingredients this country has to offer. It’s a privilege to work with some of my regular suppliers and I know that it is easy for me to source the best seasonal produce around. I also have a team of chefs on hand, as well as all the equipment a professional kitchen has to offer.

I do realise that you won’t have all this at your fingertips but this doesn’t mean that these recipes can’t be attempted by any domestic cook with a love of good food and a willingness to experiment. The recipes in this book are by no means set in stone and although I have included them in all their glory, there is no reason why you shouldn’t adapt, add or remove elements as you wish. The recipes should be used as a guideline and it is down to the individual to use their own taste buds and initiative when making a dish. When seasoning dishes the aim is to let the main ingredient shine through, with other flavours coming through and complementing it. Seasonings such as salt, pepper, sugar and lemon juice are as useful and necessary as a good set of knives and a good cook will learn how to use them to best effect.

This dish is a great summer starter. A gazpacho is meant to have some acidity, but you also need to taste the earthiness of the beetroot, which is why the recipe includes some raw beetroot. However, you also want to taste the natural sweetness of the beetroot, which is why some of the beetroot is baked. The idea is to have the perfect balance of acidity with sweetness and saltiness coming through.

Chilled Beetroot Gazpacho with Vodka Jelly and Avocado Sorbet

SERVES 4

2 kg fresh beetroot

2 large golden beetroot

1 vanilla pod

50 ml olive oil

300 ml fresh apple juice

500 ml beetroot juice

125 ml sherry vinegar

juice of 2 lemons

2 whole avocados

100 g caster sugar, plus extra for seasoning

juice and rind of 2 limes

juice of 1 lemon

2 leaves gelatine, softened

200 ml Belvedere vodka

salt

fresh coriander, to garnish

WRAP HALF THE BEETROOT and the golden beetroot in foil, place on a tray lined with rock salt and cooked in a preheated oven at 160°C/ 310°F/gas 2½ for 1–1½ hours. Leave them to sweat in the foil for 10 minutes – this will make them easier to peel. Peel the golden beetroot and use a small cutter (1.5 cm in diameter) to cut four pieces of beetroot. Peel the other cooked beetroot, cut four more pieces and chop the rest up into small pieces. Scrape the seeds from the vanilla pod and mix with the olive oil. Store the beetroot fondants in this oil.

PEEL THE REMAINING raw beetroot, chop the flesh into small pieces and place them in a blender with the cooked beetroot, the apple juice and the beetroot juice. Blend until smooth, then pass the liquid through a fine sieve by tapping the sieve; don’t try to push the pulp through the sieve, because you only want the juice. Put the liquid in a bowl over a bowl of iced water.

SEASON THE SOUP WITH SALT, gradually adding more and more until it tastes right. Then add the sherry vinegar, which will almost accentuate the salt. Then add some sugar, which should balance both the flavours. Pass again through a fine sieve and refrigerate. You will probably need to test the seasoning again once the gazpacho is fully chilled.

PEEL THE AVOCADOS and use the same cutter to cut four shapes out. Coat in lemon juice and set aside. Add the sugar to 100 ml water and bring to a boil. Blend the rest of the avocado in the blender and add the syrup. Pass through a fine sieve and add the lime juice and rind and the lemon juice. Transfer to an ice cream machine and churn until frozen.

HEAT A COUPLE of tablespoons of water in a small saucepan, add the gelatine and a small amount of the vodka and leave the gelatine to dissolve slowly. Remove the pan from the heat and add the remaining vodka. Pass the jelly through a fine sieve into a small container and set in the refrigerator for a couple of hours. It will go cloudy; do not worry.

TO SERVE, recheck the seasoning of the soup and pour it into four chilled bowls. Add the fondants, spoon in some vodka jelly and avocado sorbet and garnish with a few coriander leaves.

This is a perfect winter soup that I think is a lot easier to make than the classic French onion soup. I like to serve it with veal shin ravioli or a crisp crouton spread with some chicken liver and foie gras parfait. Remember: the younger the onions, the sweeter the soup.

White Onion and Parmesan Soup

SERVES 4

3 kg new season white onions

3 large sprigs of thyme

25 g butter

2 litres boiling white chicken stock (see page 199)

200 ml double cream

50 g very finely grated Parmesan

juice of 1 lemon

PEEL AND SLICE the onions as finely as possible, ideally using a mandolin. (The thinner you slice the onions, the quicker they will cook and the fresher the soup will taste.)

IN A WARM, covered pan slowly sweat the onions and thyme in the butter for 20–30 minutes until the onions are transparent and very soft. If you cook them too quickly they will not taste as sweet as they could, and if you cook them too slowly they will taste stewed. The idea of sweating is to cook them as quickly as possible to retain the freshness. So keep tasting every 5 minutes or so. Add the boiling chicken stock, bring back to the boil and add the cream. Return to the boil again and then blend in a blender.

WHILE THE SOUP is in the blender add the Parmesan. Be careful when you reheat the soup because the cheese tends to catch on the bottom of the pan. I add the Parmesan as if I’m adding salt, literally using it as a seasoning. Also be careful about adding salt to the soup because Parmesan is often very salty.

PASS THE SOUP through a fine sieve, then chill immediately to retain the freshness. If like, add a dash of lemon juice to finish the soup. Reheat gently to serve.

This is a perfect recipe for Christmas, which also works as a sauce for pheasant, turkey or even a firm piece of fish, such as turbot or Dover sole. The foie gras ravioli are simply for garnish – pan-fried ceps also work well. I like the soup as it is because it’s so moreish. Fresh chestnuts are definitely best. You can use precooked vacuum-packed ones, but they tend to be a bit sweet, so reduce the amount of Madeira to counterbalance the sweetness.

Chestnut Soup with Foie Gras Ravioli

SERVES 4

RAVIOLI

120 g raw foie gras, diced

10 ml sherry vinegar

2 tablespoons shallot confit (see page 210)

2 tablespoons finely shredded flat leaf parsley

75 g chicken mousse (see page 214)

100 g fresh pasta (see page 208)

SOUP

150 g fresh or vacuum-packed chestnuts

75 g shallots (peeled and sliced)

3 sprigs of thyme

25 g unsalted butter

75 ml white wine vinegar

100 ml Madeira

600 ml hot white chicken stock (see page 199)

200 ml double cream

salt

FIRST MAKE THE RAVIOLI. Season the diced foie gras with salt and fry in a hot pan until golden brown. Transfer to a plate, drizzle over the sherry vinegar over and put in the refrigerator until chilled. Mix together the diced foie gras, the shallot confit, the parsley and the chicken mousse and leave in the refrigerator for a couple of hours until it is firm. Put a large pan of boiling water with a dash of olive oil on the stove and have a bowl of iced water ready and a slotted spoon.

FEED THE FRESH PASTA through a pasta machine a couple of times on each setting, gently pulling the pasta as it goes through the machine. Take the machine down to the very finest setting and feed the pasta through at least three more times. Dust your work surface with flour, cut the sheet in half and brush half with some water. Spoon the mixture onto the wet sheet and then lay the dry sheet on top. Use a pastry cutter to cut out 4 ravioli and seal with your fingertips, making sure that all the air is forced out. Cook the ravioli for just a couple of minutes. Remove from the pan with a slotted spoon and plunge into the bowl of iced water. Drain, then drizzle with a little olive oil and refrigerate.

MAKE THE SOUP. Peel the chestnuts by piercing the dark husk. Run the point of a small knife along one side, then simply peel back the husk. An easy way to remove this is to dip the chestnuts, one at a time, into boiling water and then scrape it off while the chestnut is still warm. Slice the chestnuts as finely as possible.

IN A WARM COVERED pan sweat the shallots and thyme in the butter until the shallots are soft and transparent; do not let them colour. Season with salt, add the sliced chestnuts and cook, covered, for a further 5 minutes over a low heat; again, do not let them colour. Add the white wine vinegar, increase the heat and reduce until almost dry. Add the Madeira, reduce until dry then add the boiling stock. Bring the mixture back to the boil, then add the cream. Return the mixture to the boil, remove the thyme and then blend in a blender. Pass through a fine sieve and into a bowl over iced water to chill. Check the seasoning.

REHEAT THE SOUP and pour it into four soup bowls. Reheat the ravioli in a pan of boiling water and drop them into the soup.

The two main ingredients in this soup are in season at exactly at the same time. It is an old Spanish classic, Ajo Blanco, which can be served hot or cold. Fresh almonds can be difficult to source, even when they are in season during the summer months (July to October). When they are available I like to make the most of them. The apple jelly gives a good acidic undertone, but you could, if you like, garnish the soup with white grapes.

Chilled New Season Garlic and Almond Soup with Granny Smith Jelly

SERVES 4

2 kg new-season green almonds

2 kg new-season wet garlic

1 litre full-fat milk

100 ml single cream

50 ml sherry vinegar

100 ml dry sherry

150 ml Greek yogurt (optional)

sorrel or oxalis leaves, to garnish

salt

APPLE JELLY

7 granny smith apples

juice of 1 lemon

2 gelatine leaves, softened

100 g caster sugar

TO SHELL THE ALMONDS you will need a small tack hammer, a wooden chopping board and a steady hand. It’s best to use a tack hammer because you don’t want to crush the almonds, just crack the shell. This may take a bit of getting used to, but it’s worth being patient. As soon as you have shelled the almonds, blanch them in boiling salted water for about 10 seconds and plunge them immediately into iced water. This makes it easier to peel away the brown skin, leaving you with a bright white almond. If you can’t find fresh almonds toast 150 g flaked almonds just long enough to release the oils and flavour. Drop them into the cream to infuse with a drop or two of almond extract or oil.

PEEL THE GARLIC. This will be easier than peeling normal, aged garlic because the skin will almost fall away. Put the garlic in a saucepan and cover with one-quarter of the milk. Bring to the boil, simmer for 5 minutes and then drain the milk away. Cover with another quarter of the milk and repeat the process until all the milk has gone. Once cooked, the garlic should be so soft that you can almost squash the cloves between your fingertips.

PUT THE GARLIC, almonds and cream in a saucepan. (If you are using almond-flavoured cream drain away the almonds and cover the garlic with the cream.) Heat and simmer for 5 minutes, stirring until smooth.

PASS THE MIXTURE through your finest sieve and chill immediately over a bowl of iced water. If you are going to serve the soup cold, wait until it’s chilled before you season. If you are going too serve it hot, season it before chilling. Season with salt, sherry vinegar and dry sherry. The sherry vinegar and the dry sherry will cut through the richness and give the soup a really fresh taste. If you are serving it cold it will benefit from a little Greek yogurt being mixed in just before you serve.

MAKE THE APPLE JELLY. Peel six of the apples and keep the skins separate. Juice the apples in a vegetable juicer and transfer the liquid to a saucepan. Bring the juice to the boil, remove from the heat immediately and pass through a muslin cloth or very fine sieve. You will have a clear apple juice. While the juice is still hot put it in a blender with the reserved apple peel and blend until the juice is bright green. Add a squeeze of lemon juice, the gelatine and the sugar. Strain again into a bowl set above iced water. When the jelly begins to set slightly transfer it to the refrigerator for at least 2 hours. Finely shred the remaining apple.

TO SERVE, pour the soup into bowls (chilled if the soup is cold) and spoon some jelly in the centre. Garnish with shredded apple, sorrel leaves or, as here, oxalis leaves, which have a similar flavour to Granny Smith apples.

GROWING BABY SALADS IN WILTSHIRE

I firmly believe that vegetables, herbs and fruits are a cook’s greatest asset. Any cook who thinks vegetables are the least interesting part of a meal, a bore to prepare, and a mere garnish to meat or fish, is totally missing the point. As far as I’m concerned, vegetables are a staple, central to a dish, the real deal. A lot of my dishes are based around fruits or vegetables – meat, fish or dairy is quite often an afterthought, something to fill the dish out.

Today there really are no excuses for not using organically grown fruit and vegetables. I could almost guarantee that if you were to have your vegetables delivered each week by one of the many box schemes working hard to change the way we think about organic produce, you would spend the same amount of money as you would do filling your stainless steel trolley on a Saturday afternoon. Plus, it would make you think a little more about what you cook, and you would discover new flavours and combinations.

Food miles (how far your carrot, potato or apple flew, aided by fossil fuel, in order to sit on your plate) is a big issue for enviromentalists. I try to buy British produce when it’s in season but when I have to I choose imported produce from a source I know is benefiting the people growing it. Britain could be much more self-sufficient and not import out-of-season produce from far flung places – but only if the supermarkets were prepared to pay a fair price for them. Also, if Britain’s farmers grew a greater variety of crops, they would live less under the threat of abandonment by supermarket buyers.

Greengrocers are fast disappearing from the British high street. They find it too much of a struggle to compete on price with the supermarkets. If you have a greengrocer near you – support it! They buy their produce straight from the traditional wholesale market, who buy straight from the grower. This simple supply chain means you can buy vegetables that were picked the previous afternoon, and you will taste the freshness. Again it’s a question of pester power; ask your greengrocer to sell the vegetables and fruit at the time of year you want them and when they are at their best.

However, it is not all doom and gloom as smaller chains of supermarkets build long-term relationships with farmers. Some support watercress growers in the South, and rhubarb growers in Yorkshire. Others encourage farmers to grow specialist vegetables such as wild mushrooms, violet pearl aubergines and spiny artichokes. I would love to see fields of artichokes growing in Yorkshire and sweet peppers in Devon’s greenhouses.

A true ambassador to the cause is someone who has been a great friend of mine for almost ten years, Richard Vine from R.V. Salads based in Wiltshire. He is the maestro of all things very small. Richard’s passion is now centred fully on growing micro salads after a career as a livestock producer and organic vegetable producer. He now runs a highly successful operation supplying England’s best restaurants with ingredients that simply were not available seven or eight years ago.