20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Crowood Wargaming Guides

- Sprache: Englisch

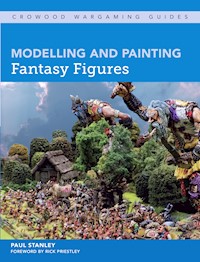

Aimed at modellers of all abilities, this lavishly illustrated book presents a step-by-step guide to figure painting and modelling using traditional techniques. From the multipart hard-plastic 28mm miniature to the metal and resin models common in all other scales, this book provides wargamers, collectors and gamers with a wealth of information to achieve the best results. It demonstrates a variety of modelling and painting techniques at different scales; it provides step-by-step guidance on building, converting and painting models; it covers working in plastic, resin and white metal; it explains dry brushing techniques, the three-colour method, multilayering and shading with washes and, finally, it considers basing techniques and maintaining the compatibility of miniatures between different gaming systems.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 257

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

MODELLING AND PAINTING

Science Fiction Miniatures

MODELLING AND PAINTING

Science Fiction Miniatures

PAUL STANLEY

FOREWORD BY RICK PRIESTLEY

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Paul Stanley 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 827 6

CONTENTS

Foreword

What an unexpected treat to discover that Paul Stanley has added a brand-new volume to the Crowood Wargaming Guide series – this time covering a wide range of science fiction and futuristic subjects. Gamers, collectors and painters who already possess Paul’s excellent first volume will rightly anticipate a book crammed with much practical information, enlightened by the experience of one of our premier painters and modelling experts. Well here it is – not only a wonderful resource of ideas and techniques, but beautifully photographed and illustrated to boot.

Despite the encroachment of technology upon our everyday lives, the fascinating hobbies of model making, painting and tabletop gaming continue to flourish as never before. When it comes to the kind of futuristic subjects presented in this volume our inspiration may come from movies or TV, or perhaps from the pages of a book – and let us be grateful that ‘paper technology’ has not yet been surpassed by video and the wonders of the internet.

Nonetheless, more than any other genre, ‘science fiction’ continues to evolve apace, its ever-changing vision reflecting our hopes and dreams, and sometimes our very darkest fears. Perhaps it is because the realm of science fiction remains uniquely the stuff of our imagination that it attracts our attention as it does: endeavours that have yielded some of the very best by way of model design, games of all kinds, painting, diorama building and terrain making.

It is curious to reflect that many of the materials now available to the aspiring modeller and painter were themselves the stuff of ‘science fiction’ not so many years ago. Some are improvements upon time-honoured materials such as paints and adhesives; others are recent developments such as weathering powders and pre-prepared washes and dips. All of these are considered and their various uses described and illustrated.

Modern paints and adhesives certainly make life easier for all of us, whatever our aim or level of skill. Developments in materials have inspired experienced modellers to invent new techniques, such as the Zenith Primer method of reproducing directional lighting effects. Another spur to our efforts comes from the quality and availability of modern commercial model kits, whether plastic, metal or resin, exhibiting a level of detail and finesse of finish far surpassing those offered for sale in times not far past. What better time could there be to re-consider the methods and techniques of our hobby in a fresh light?

This volume comprises an up-to-date guide to the world of science fiction collecting, painting and modelling, and will no doubt find its way onto the bookshelves of both aspiring artists and experienced brush-smiths alike. It is a book that is crammed with ideas as well as a great deal of practical information. Basics like assembly and preparation are covered in a clear, no-nonsense way, whilst more advanced concepts such as converting and sculpting detail are described and illustrated with clear photographs. Machines of all kinds loom large in the science fiction genre and receive their proper due here too, with a whole chapter devoted to assembling and converting vehicles, and another to painting both vehicles and armoured men and machines. For diorama builders and those who want to take their modelling a step further, advanced detailing and weathering are considered too.

All this, illustrated in the most generous and beautiful manner, gives us a book that is a treat to look at; and who cannot but be inspired by the sight of such gorgeous and expert modelling, carefully selected and professionally photographed? Anyone seeking to put together a collection for gaming purposes will find all the practical advice they could hope for. Artists and modellers looking to expand their skills will discover new ideas that will enable them to meet whatever challenges they have set themselves.

Whatever our aspirations we are surely lucky indeed to have such a dedicated and thorough exponent of miniature artistry to guide us.

Rick Priestley

Preface and Acknowledgements

Having completed my first book for Crowood, Modelling and Painting Fantasy Figures, I now have the privilege of presenting my second, Modelling and Painting Science Fiction Miniatures, which in many respects can be considered a companion to the first. Indeed, for many wargamers of my generation the two genres are inseparable, having grown up with an obligatory collection of miniatures that not only included models for Fantasy RPGs (Role Playing Games) but SF (Science Fiction) role playing also.

Although other wargaming rules were in existence at the time, playing SF or fantasy tabletop wargames in the early 1980s meant my friends and I were initially using rules with a focus that was predominantly on role-playing. These included ‘Advanced Dungeons and Dragons’ by E. Gary Gygax (AD&D), which satisfied our desire to indulge in fantasy, and two SF RPGs: ‘Traveller’, published in 1977 by Games Designer’s Workshop, and ‘Spacefarers’, published in 1981 by a similarly named but unrelated company called Games Workshop Ltd.

The latter of these two companies would, unbeknown to us at the time, go on to become a household name and was, at the time, responsible for introducing my generation to a smorgasbord of games and miniatures in both the fantasy and SF genres. The miniatures that we collected and painted were produced to accompany games such as ‘Battlecars’, ‘Doctor Who’, ‘Judge Dread’ and ‘Paranoia’ until the emergence of ‘Warhammer 40,000 Rogue Trader’ in 1987 – a game that evolved into ‘Warhammer 40K’ or WH40K as we know it today. Little did we realize what would transpire, as we saved up our pocket money for the release in 1985 of a handful of unassuming, limited edition, SF models by Citadel Miniatures. Models such as LE01 Space Orc, LE02 Imperial Space Marine and LE06 Space Santa were the three that I was proud to own – and in fact still do, all these years later.

A Cthulhu adventure game typical of those played in the 1980s by the young author, where models of non-player characters were painted black to maintain a sense of mystery.

The author enjoying an SF skirmish game with Rick Priestley, writer of many wargaming rules including Warhammer 40K and The Gates of Antares.

The early to mid-1980s were exciting times in which to be involved with the hobby. The arrival of a chunky 25mm Space Orc and an Imperial Space Marine festooned with a level of detail not previously seen on SF miniatures suddenly gave me a reason, and a need, to paint wires, push-buttons, tactical scopes and scanner screens in vibrant and fluorescent colours. Not only that, but the dark world of ‘Call of Cthulhu’, an RPG released in 1981, forced me and others to explore how we might paint our miniatures in order to get the most enjoyment from a game. Whilst for Warhammer we competed with one another to create brightly coloured armies, depicting different SF races in vibrant hues, for games such as ‘AD&D’ or ‘Cthulhu’ we found that beautifully painted models were a distinct hinderance. When wargaming, colourful miniatures convey a great deal of useful information about the race, skills and capability of an adversary. In some respects this can be advantageous as it serves to intimidate an opponent. Equally in WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) wargames it clears up any ambiguity. If the model is holding a scatter gun then it is fighting with a scatter gun. In RPG adventures, however, we soon discovered that lavishly painted models, accurately depicting a creature from a Monster Manual, diminished our enjoyment of the game as they gave away too much information or caused arguments about whether or not using an unrelated model constituted a rule book infraction. This would in turn undermine any attempt on the part of the DM (Dungeon Master) to create suspense or keep the players guessing as to what foe they were actually facing. Nothing ruined an RPG more quickly than an experienced player shouting out the identity of a creature before the DM had placed the model on the board. This issue would force us, as both gamers and modellers, to innovate and, as with all miniature painters and wargamers the world over, we have been innovating ever since.

Writing this book has again given me the opportunity to revisit my youth and connect once more with the enthusiasm for miniature modelling that defined that period in my life. It has also provided me, as someone who is more used to spending their time sculpting miniatures, with a rare opportunity to paint them instead. I hope that you will enjoy reading about the concepts, techniques and tips contained within these pages as much as I have enjoyed writing about them. As we enter a new era in production materials, painting techniques and games design, may we never stop innovating.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Once again I am indebted to Rick Priestley for his generous contribution to this book, not only in writing the Foreword but in the advice he has kindly provided and also in allowing me to photograph models from his personal collection, some of which are included in this volume. A huge thank you also to the Ansell family, Bryan, Diane and Marcus (Wargames Foundry) and Maria (Warmonger Miniatures) for all their support and for allowing access to Bryan’s personal miniatures collection, which includes many wonderful and memorable examples that I remember from my childhood. Thanks also to Paul Sawyer (Warlord Games), Ed Pugh (Reaper Miniatures), Andy Lyon (Ainsty Castings), Maciej Liwanowski (Kromlech), Victoria Lamb (Victoria Miniatures), Rob (Mantic Games), Kev Stillyards (Bridge Miniatures), Karl Pemberton (Crooked Dice Studios), Hudson Adams (Wargames Atlantic), John Fielding (Vanguard Miniatures), Jon Tuffley (Ground Zero Games), Ian Marsh (Eureka Miniatures), Darrell Henson (LCA – Lasercut Architects), Wendy Cooper and Antony Spencer (West Wind Productions), Nick Eyre (North Star Miniatures), Rob Alderman (formerly of Hysterical Games), Anthony Meekings (Debris of War), Andrew Taylor (Antediluvian Miniatures), Martin and Diane (Warbases), Fireforge Games, Secret Weapon Miniatures, Spiral Arm Studios and Sarissa-Precision Ltd.

Kind thanks go out to Steve Dean for allowing me to include more examples of his work in this second book and for supplying those particular photographs.

Thanks also to my friend John (Big John) Robson, who gave me his late father’s unfinished 1/48 scale Mercantic by Billing Boats, which has become the eye-catching rusted hulk of a 28mm wreck that regularly features on the gaming table.

And finally, big thanks to Nathan Long and all the guys at Mighty Lancer Games for their help and hospitality, and for allowing me to use photographs of their establishment within this book.

Introduction

PEER INTO THE world of science fiction (SF) wargaming and modelling, and you will find a place seemingly dominated by one company and one game, Games Workshop and ‘Warhammer 40K’ (WH40K). Look a little more closely, however, and what you see is a thriving community of modellers, gamers and manufacturers, involved in, and gaining enjoyment from, a myriad of different games and modelling activities within the genre. A selection of these boutique models is featured in the pages of this book. Whether you love the organization or hate it, what cannot be denied is that the industry in general, and the gaming community as a whole, owes a debt of gratitude to Games Workshop and the early pioneers who helped create and grow the company during those formative years. In particular, to pioneers such as Steve Jackson, Ian Livingstone and Bryan Ansell, whose vision and creative drive took a company that was producing wooden board games such as ‘backgammon’ and ‘nine-men’s-morris’ in 1975, and turned it into the global phenomenon we know today. Having once imported wargames and role-playing games, the company they created became a developer, publisher and producer of games and miniatures in its own right. Other pioneers such as Rick Priestley who, together with Bryan Ansell and Richard Halliwell, created the ‘Warhammer Fantasy Battle’ game for Games Workshop in 1983, to be followed, before the decade was out, by Rick’s SF rules, realized with the release of ‘Warhammer 40,000 Rogue Trader’ in 1987.

Described by its creator as a fantasy game set in the far future, WH40K would go on to shape not just the way in which SF wargames were played but the manner in which the entire gaming genre is perceived. From humble beginnings that arguably started with the release in 1985 of a handful of limited-edition miniatures, would emerge a game that now has a worldwide market and a global following. Among the 25mm scale LE01 Space Orc, LE06 Space Santa and LE09 Space Skeleton, all sculpted by Bob Naismith for Citadel Miniatures, was the LE02 Imperial Space Marine, the very first Space Marine ever owned by many of the author’s generation. This white metal model of a man in power armour, his face hidden behind the pointed visor of a helmet that clearly drew inspiration from those worn by knights of old, was the embodiment of the fantasy warrior in a futuristic age. To all intents and purposes a Space Marine was, and still remains, a machine-gun wielding, medieval knight in high-tech power armour. The design, execution and overall appearance of Space Marine models has been extremely successful, so much so that in 2016 the thirtieth anniversary of the original model (LE02) was celebrated with the release of a modern-day interpretation. So distinctive is the appearance of this particular Space Marine that it would become known as a style in its own right. When subsequent variations in helmet design resulted in models more reminiscent of the Star Wars Storm Troopers, those models that retained the original pointed helmet became affectionately known as ‘Beakies’ or ‘Beaky Marines’ and they are very much sought after to this day.

At the same time that WH40K was emerging, Games Workshop was also offering a wide range of other SF RPGs and combat-related board games, including ‘Paranoia’, ‘Judge Dredd’, ‘Golden Heroes’, ‘Chainsaw Warriors’, ‘Battlecars’, ‘Doctor Who’ and ‘Call of Cthulhu’ to add to a list in which ‘Spacefarers’ and ‘Traveller’ were already well established. ‘Traveller’, produced by Games Designer’s Workshop Inc in America, was a 15mm scale SF RPG imported into the UK by Games Workshop and for which Citadel Miniature supplied a range of figures.

Another game worthy of note was ‘BattleTech’, launched by FASA Corporation in 1984. Featuring towering robots that were based loosely on Japanese animation imagery, borrowed under a licensing agreement, these huge anthropomorphic androids battled one another in a futuristic but feudalistic dark-age setting. The popularity of this game (and the miniatures produced for it by Ral Partha) did not go unnoticed by Games Workshop, who not only imported and distributed but also produced many miniatures to accompany other games by FASA. These included the ‘Star Trek’ and ‘Doctor Who’ RPGs. In an attempt to capitalize on the popularity of ‘BattleTech’, Games Workshop went on to create ‘Epic 40,000’, which was a 6mm scale interpretation of their successful WH40K universe in which wargamers could field immense machines such as Titans and mega tanks. Within the space of less than a decade the three distinct miniature scales that would dominate SF wargaming and modelling for years to come had emerged.

In 2001 Games Workshop released ‘Inquisitor’, which used 54mm scale miniatures. Written by Gav Thorpe and described as a narrative wargame, according to its creator it differed from other tabletop wargames in that the main aim was to use the miniatures and rules to create a story on the tabletop. In reality most players simply enjoyed the extra level of detail involved in recording wounds at this scale, together with the additional depth provided by a game that enabled fighting from upper levels and rooftops, as they shot each other to pieces in ways not possible in conventional tabletop wargaming. In this respect the author was no exception. It could therefore be argued that by 2001 Games Workshop had created a repertoire of SF games and miniature ranges that competed directly with successful games from rival manufactures and would go on to influence future offerings developed by smaller, more boutique manufacturers.

With WH40K as their most successful title, other spin-off rulesets that served as extensions to the 40K universe were sold by Games Workshop under the ‘Specialist Games’ umbrella. In addition to the 6mm ‘Epic 40k’ and the 54mm ‘Inquisitor’ games already mentioned, the umbrella also included: ‘Necromunda’ (released in 1995), a 28mm scale futuristic game of gang warfare; ‘Gorkamorka’ (released in 1997) a skirmish game involving Mad Max-style vehicles driven by Orks; and ‘Battlefleet Gothic’ (released in 1999), a wargame in which fleets of interstellar warships fight one another. To some extent the latter of these was a natural progression, following on from the days when Games Workshop distributed FASA’s ‘Star Trek’ RPG and ‘Star Cruiser’, which was an extension to the very popular ‘Traveller’ SF RPG by Games Designer’s Workshop. Both of these games had their own ranges of space vessels manufactured at the time by Citadel Miniatures.

The internet may have changed the way we shop forever but nothing beats the rewarding feeling of being able to walk into your local store and see the models before you buy them. The author makes his choice … and pays his money.

Local gaming stores can provide great opportunities to meet fellow hobbyists, learn new games and share hints and tips on modelling and painting SF miniatures.

Having acknowledged the significant influence that Games Workshop and Citadel Miniatures have undoubtedly had on shaping SF gaming and modelling, and the dominant force that is WH40K, they are not the be-all and end-all of the industry, nor every gamer’s or modeller’s preferred choice. The list of SF tabletop games is extensive and since the early 1980s many have come and gone whilst new ones continue to emerge on an almost monthly basis, particularly in a new era of kickstarters and crowd funding. Additionally, the internet has changed the way we buy our games and miniatures almost beyond recognition, opening up manufacturers and suppliers quite literally to an entire world of new customers.

Popular computer games such as ‘DOOM’, graphic novels such as 2000AD and successful TV shows such as The Walking Dead have all been successfully turned into board games. Each comes with its own range of 28mm miniatures that can be painted and used on the wargaming table. Brand new SF mass-combat and squad-level games in the shape of ‘Warpath’ from Mantic Games or ‘Beyond the Gates of Antares’ from Warlord Games – the latter written by the creator of WH40K, Rick Priestley – all serve to provide the modeller with far more choice now than ever before. In the face of such diversity, many gaming stores not only sell these games but also provide areas in which they can be played and, in some cases, provide tables for customers so that they can build and paint their models in-store while in the company of friends and fellow enthusiasts.

Scratch-built planets and asteroids provide the setting for these battling spaceships, which are produced by both Vanguard Miniatures (left) and Ground Zero Games (right).

This book aims to explore the fundamental aspects of SF modelling across the board, not just with regard to the effects that can be achieved as modelling materials and techniques evolve, but also in respect of the models being produced for any particular game. What can be realized when modelling at the tiny 6mm scales of Epic and BattleTech, for example, is very different from the final outcome achieved in the popular 28mm scale of most miniature games or the even larger 54mm scale. The informative step-by-step guides will offer hints and tips to help modellers achieve eye-catching results in all of the popular SF scales, using contemporary models from a wide range of manufactures active in today’s SF hobby.

The processes covered within the pages of this book do not need to be followed to the letter or adhered to regimentally. They are intended as a starting point from which experienced modellers and novices alike can adapt and enhance each technique to suit their own personal needs and tastes. The watchword is enjoyment. Above all be confident, be creative and have fun with your miniature modelling.

1

Tools, Equipment and Modelling Materials

WHEN DEDICATED HOBBYISTS choose to share photographs of their painting desks online, so that we are lucky enough to see the products and materials that they use, the sight of each workspace crammed full of so many different paints, brushes and tools can be extremely inspiring, if not rather daunting. It is easy to forget, however, that amassing a comprehensive collection of tools and paints, more often than not, takes a considerable length of time. Purchasing equipment and materials as and when required, on a project-by-project basis, is a sensible way to spread the cost, particularly as those who are new to the hobby may be without any tools or paints when they decide to take the plunge. In this case a simple starter paint set may prove a worthwhile investment and may also be the most affordable way to begin modelling. Many of these sets contain all the colours that are needed to paint a particular range of miniatures, while some even include a small selection of models to paint. These paint sets allow the modeller to dive straight in without the initial burden of a substantial outlay in costs. With a miniature or two, a handful of paints, a couple of brushes, a craft knife, the right glue and a few additional household items including kitchen roll, an old plate and a mug of water, modelling can begin in earnest. It is worth pointing out, however, that for all the convenience and value-for-money offered by these starter sets, the limited range of colours tailored to one paint scheme, style of uniform or camouflage pattern can make it difficult to mix any additional colours that might be needed.

A typical painting desk and a familiar sight to many of today’s dedicated hobbyists. This one belongs to the author.

Conventional wisdom suggests that purchasing a primary palette of red, blue and yellow, together with black, white, silver and gold, gives the modeller the capacity to mix almost any colour that might be needed across a multitude of different painting projects. This thinking is based on what is commonly taught at school, and conventional colour theory is explained in my previous book, Painting and Modelling Fantasy Figures (Crowood). The more astute modellers among us have, however, come to realize that the conventional colour theory that we are all taught at school is basically a lie. Rather than relying on red, blue and yellow pigments which, when mixed, often result in muddy colours, miniature painters are now gravitating towards the colour palette used in the printing industry. When choosing paints, they are selecting cyan, magenta, yellow and black – collectively known as CMYK – and from those they find that they can mix many of the more vibrant colours.

CMYK VERSUS CONVENTIONAL COLOUR THEORY

Whether flawed or not, an understanding of colour theory is one thing that most miniature painters will find useful, and for those hobbyists seeking to mix their own paint colours it is essential. Whilst an in-depth study into colour theory and the colour wheel lies beyond the scope of this book, a brief explanation is provided here. Those modellers wishing to explore the topic further, and examine the arguments for and against the primary palette versus CMYK, will find ample material on the internet and YouTube to satisfy their curiosity and further fuel the debate.

The principles of colour theory are well known and widely used, but the wisdom of conventional thinking is now being questioned.

Many painters are now choosing to use the CMYK palette in addition to the primary colours of the colour theory popularly taught in schools.

Traditionally we are all taught at school that the three primary colour pigments are red, yellow and blue, and that by mixing these three pigments, in various combinations and proportions, it is possible to create any other colour within the visible spectrum. Well, yes and no. A primary colour is defined as a colour that cannot be mixed by using any other colour, yet red pigment is made by mixing yellow and magenta, hence the debate. A secondary colour is one that is obtained by mixing any two primary colours in equal amounts and so the argument exists that red is therefore a secondary colour. Again we are taught in school that secondary colours are orange (from red and yellow), green (from yellow and blue) and purple (from blue and red), and that tertiary colours are in turn created by mixing secondary colours with one of their constituent primary colours. In practice, when these colours are blended together on the palette, they frequently produce pigments that appear dull or muddy, and thus the folly of conventional wisdom is exposed.

If we take a quick look at any inkjet printer, of the kind commonly found in the home, we see that they print using four pigments. These are not the primary colours of red, yellow and blue but are instead cyan, magenta, yellow and black, or CMYK. These are the four pigments used by the printing industry when printing in full colour. Why then, if red, yellow and blue are primary colours that cannot be made by mixing any other colour, do we not put these colours into our inkjet printers?

If we look at both the conventional primary colours and the CMYK colours we find that yellow is clearly a colour we cannot make by mixing any other colours. If we mix yellow with magenta we get red, so red cannot be a true primary colour. If we want to make cyan we find this is another colour we cannot make, but mixing cyan, magenta and a little black gives us a dark blue so blue cannot be a primary colour either. Finally we are taught that mixing blue with yellow gives us green, but how many of us discover to our cost that when we do this with acrylics, the result is always a dirty olive green? A truly vibrant green can only be achieved by mixing yellow with cyan. Without getting distracted by arguments concerning what the true primary colours are, or our perception of reflected colour versus colour projected from a light source, and a myriad other issues, it is clear that any basic colour palette should include cyan, magenta, yellow and black in addition to red, dark or navy blue and a vibrant green, not to mention white, silver and gold. At least that way, if we are mixing our own paints, we can be sure of some success with the final outcome.

Many of today’s comprehensive paint sets have significantly reduced the need to mix paints, if not negating it altogether. Understanding the relationship between colours remains something of great value, though. Colours that oppose one another on the colour wheel are known as complementary colours. These complementary pairs include red and green, yellow and purple, and blue and orange. When used in combination, paint schemes comprising of complementary colours can produce an extremely powerful visual impact. Using colours that appear next to one another on the colour wheel such as purple and blue, blue and green, green and yellow, yellow and orange, and so on will, on the other hand, give results that are harmonized.

Taking a pair of complementary colours and adding white to one and black to the other will produce a discord colour, so for example red and green becomes either pink (red plus white) and dark green (green plus black) or burgundy (red plus black) and pale green (green plus white). Once we have mastered these basic behaviours, we are free to create colour schemes to fulfil almost any need imaginable.

As a final word on mixing metallics, adding black to silver will produce dark shades of steel, adding a little red to gold will produce brass and adding a small amount of black to that will, in turn, produce a dark copper shade. With that in mind we can now turn to the other tools that will be required, starting with brushes.

BRUSHES

It is easy to forget that brushes are consumable items and that over time they will wear out. Some painting tasks can be extremely punishing on brushes, while others require only a light and delicate touch, so buying the right brush for the job is critical. Owning a range of brushes in different shapes and sizes is essential.

A good selection of brushes will be required, from small ones for detailing tiny areas through to large ones for dry brushing, applying washes and painting big models.

Detailing Brushes

Whilst it is possible to economize by using cheap or old brushes for many of the basic painting tasks, when it comes to detailing miniatures, only the best will do. If nothing else, investing in a small number of high-quality detailing brushes, with sable bristles, will help to produce superior results when painting models. Although sable brushes do cost more than their synthetic counterparts, they will last far longer if good care is taken of them. In this respect the cheaper alternatives really are a false economy.