Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

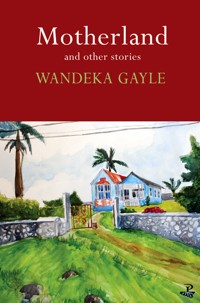

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Wandeka Gayle's mostly young black women protagonists win our hearts as risk-taking, adventurous explorers of the white world, away from home, which at some point has been Jamaica. They include Roxanne who starts work in a care home in London, who strikes up a rapport with a depressed old man who used to be a writer; Ayo who heads to college in Louisiana, and fights off the internalised voice of her godly, tambourine-beating aunt to begin an affair with an engaging, slightly older white man; there's Sophia who comes to work in Georgia, who struggles to know whether her inability to engage more deeply with other people is really about racism or, rather, a more personally embedded reluctance. What characterises these women is a readiness to encounter, an attempt to get to grips with the oddities and strangeness of the white world, and like Ayo to engage with it, whilst being pretty sure that Forrest "could never understand her world". They take risks and are sometimes forced to pay for their courage. Other characters have to confront situations of their own making, like Angela returning from the USA for her mother's funeral, trying to find some point of contact with the now almost grown children she abandoned, or Melba who, after her husband dies, must confront the silence she has permitted in their marriage. The situations that Wandeka Gayle writes about are in the main the stuff of everyday life, but she writes with such an empathy, grace and acute psychological understanding that one cannot but engage with her characters. There's an easy democracy of inwardness with them, too; she is as much at home with the ill-educated, apparently ambitionless and illiterate, as with a sophisticated lecturer like Michel meeting up with an old flame at a literary conference.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WANDEKA GAYLE

MOTHERLAND

AND OTHER STORIES

First published in Great Britain in 2020

This ebook edition published in 2021

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

© 2021 Wandeka Gayle

ISBN 9781845234799 (Print)

ISBN 9781845234804 (Epub)

ISBN 9781845234812 (Mobi)

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It took a lot of support for me to create these stories about my beloved Caribbean people at home and abroad, drawn from memory, imagination and longing. The stories were written over several years and were first compiled in part as an element of my dissertation while I completed doctoral studies at the University of Lafayette in Louisiana in the Spring of 2018. I am eternally grateful for the guidance and support of acclaimed writer, John McNally, who chaired the committee and whom I still consider a mentor, and for the support of committee members Joanna Davis McElligatt, who inspired me to keep going when I often felt too different and isolated as a black Caribbean immigrant in a predominantly white institution, and Maria Seger for her infectious enthusiasm and encouragement through the process.

I would like to thank my family for their continued support, to my parents, Wezley Snr. and Sandra, for instilling a strong reading culture in their children from a very young age and for demonstrating the importance of stories; and to my siblings, Shawnette, Wezyann, Sanya and Wezley Jr. who have enriched my life and who inadvertently offered me material for stories through our very colourful conversations over the years.

To all my friends who became first readers of my work, especially Nikeisha Davis Jackson and Jason Knight, who continue to give me moral support.

To the black American, African and Caribbean fiction writers of Kimbilio Fiction and the Callaloo Creative Writer’s Workshop who provided a safe haven, love, and vigorous critique of my work during our summer fellowships in the hills of New Mexico and the halls of Oxford University, where some of this work was conceived and produced.

Thank you to my second-form English teacher, Amos Thompson, who told me I would one day write a book, even before my thirteen-year-old mind could fully embrace that fact, and to all my writing professors who helped me to cultivate my love of words.

I must also acknowledge the literary journals and magazines where some of the stories found their first home:

My deepest appreciation to:

Transition Magazine, who published “The Blackout” in Fall 2020 in Issue 129; Prairie Schooner, who published “Walker Woman” in the Summer of 2020; Blood Orange Review, who published a version of “The Wish” in Spring 2020; Kweli Journal, for publishing “Prodigal” in Fall 2019, and for nominating it for the O. Henry Prize Stories 2020; Pleiades, for publishing a version of “Help Wanted” in Summer 2019, and for nominating it for a Pushcart Prize; midnight & indigo, for publishing “Finding Joy” in their inaugural issue in Winter 2018; Interviewing The Caribbean, for publishing “Cecile” in Winter 2018; Moko, A Journal of Caribbean Art and Letters, for publishing “Birdie” in November 2018; Aaduna, for publishing a version of “Reunion” (formerly “The Encounter”) in Summer 2017; Susumba, for publishing “Melba” in Summer 2016. Thank you to Jeremy Poynting and team for giving them all a home.

Most of all, thank you to the divine muse, the ancestors, both literary and spiritual, and the preservers of the ancient, oral tradition whose folktales continue to inspire my work.

Thank you to all those who have said an encouraging word or found joy and meaning from my stories.

CONTENTS

Motherland

Finding Joy

The Wish

Walker Woman

Help Wanted

Court Room 5

Melba

The Blackout

Birdie

Reunion

Prodigal

Cecile

Dedication

This is dedicated to all my black Caribbean women at home and abroad,whose stories the world often ignores.

I see you.

MOTHERLAND

Roxanne ran her hand over her tunic and looked down at her sturdy, white flats. She gazed out at the fog that hung like an omen over the street. She frowned at her reflection in the window. The damp made her short curls puffy and she had lost a few pounds, so her collarbone jutted out against the starkness of her uniform.

When she first arrived in London, she’d felt a surge of purpose and something akin to happiness. Maybe the towering old buildings, the tube and the double-decker red buses made her feel she’d moved on from Red Ground. She hadn’t minded the perpetual cloudiness at first and the constant drinking of tea was comforting, even if there wasn’t a sprig of fever grass or cerasee bush like her granny used to make.

“You have to have steel in you blood if you going over there,” her father had said. “Is not like out here at all, at all.”

“Don’t frighten the child, Merlin,” her granny had said.

“Well, some people think foreign is nice. Who feels it knows it.”

He had gone to England in the fifties as a teenager, to what he still referred to as the motherland. He’d returned to Jamaica in the seventies, disillusioned. She had been born ten years after his return, when his resentment had crystallized into bitter rhetoric.

Would he be turning in his grave if he knew she had followed his footsteps? This was her life. Besides, he had hardly been around, leaving her with her grandparents after Roxanne’s mother died. It was them she missed the most, but there was no going back; there was no one to go back to.

Six months before, she had looked down at her grandfather’s face in the casket. How proper and polished he’d looked, hands crossed reverently across his chest. She had smiled to think how he would have laughed himself silly to see himself dressed in a crisp white shirt and a black, pinstriped suit.

Papa Jenkins had never worn a suit, even when he’d been forced to attend the Presbyterian church at the top of the hill – twice in the thirty-five years he had lived in Red Ground with the eternal red stain of the yam hills; there was no sense in washing it off when he was going back to dig some more the next day.

Papa’s sister, Yvette, had offered to take her back with her to London after the funeral and Roxanne had agreed. This was before she discovered she was more housekeeper than house guest – ironing, washing, cooking, and cleaning. Finding a job and a flat of her own became an obsession; after three months, she was able to slip away.

Now, she was beginning to see beyond the museums and the quaint little cafes and long for the red dirt and her granny’s cooking. She remembered that first morning at the care home when she popped her head in a room, looking for the office, and saw some staff members holding down an old man who vehemently refused to take his medicine. She learned later that he had refused to take it because the new nurse was Nigerian.

The Sunshine Nursing Home had near gothic stone walls and a general dreariness. Some days she looked down the gloomy corridors and expected to see shadowy figures flitting down them. It would be an awful place to come to die.

It was bad enough that she had to live above a middle-aged woman who stole the coins they needed to feed the electricity meter to buy her cigars, who insulted her at every turn.

“Do you practice voodoo or obeah in Jamaica?” Miss Carmen asked. “What about marijuana? I don’t think our landlady would like that one bit.”

The girls with whom she shared the upstairs rooms, American Fiona and Kenyan Asha, assured her she would get used to Miss Carmen but she never ceased to be amazed at the things that rolled out of the woman’s mouth without seeming rancour.

“Dear me, those Asians can’t speak to save their lives, but they do know how to make those darling little dumplings… Those Pakis are taking over our streets with their ramshackle little shops… I love children about age two. Don’t they look darling in their little jackets and mittens during winter, even the little dark ones?” And on and on…

“She better stop talking like that or one day, I go smack the dentures right out her head,” Roxanne told Fiona.

Fiona laughed. “I just need to do one more semester and I’m getting the hell out of this house.”

“You miss home too?” Roxanne asked.

Fiona smiled and turned grey eyes on her. They were stark in her brown face. She shrugged and slipped two giant hoops through her ear lobes.

“I mean. I shouldn’t say it like that. It’s not so bad with you here,” she said. “Besides, why stress when you can go dancing? Right? You coming?”

Roxanne shook her head and began to peel off her uniform.

*

The next few weeks seemed to bleed into each other at Sunnyside. Two beds became vacant after their owners succumbed to a heart attack and kidney failure respectively. A new resident now occupied Room 38.

He was heavy set and sombre. No one had come to visit him. He sat sullenly by the window in his narrow room all day.

“Big writer, once. Harold Smith. Could scarcely believe it when I saw his file. No one’s seen him in years,” Ethel said, adjusting the tray of food in her hands.

Ethel was round and pale, with bright blue eyes and red hair that escaped from a bun to curl wildly around her face. She regularly slipped Roxanne titbits of gossip, seeming to know more even than Mrs. Cunningham.

“Sad, ain’t it? Now they just drop ’im off here like a regular fellow.”

Two days later, Roxanne went in Room 38 with an armful of fresh linen.

“Mr. Smith, I have to change the sheets.”

He remained motionless in his chair.

“They said you have to get your dinner in the dining hall from now on.”

She quickly stripped the sheets, then walked closer to look at him. His pale blue eyes seemed unfocused. Her pulse quickened. She had seen it done before, but had never had to check to see if someone had expired. She took a deep breath, gulped and began to reach out two fingers to his neck. Then, he blinked. She jumped and quickly ran back to the bed to put on the new white sheets.

As Roxanne fluffed the pillow, she noted the solitary picture on the night table of a cherub-pink face framed with wild curls.

“Is your granddaughter that?”

He didn’t turn around.

“She’s cute.”

Roxanne balled up the dirty linen and began to head for the door.

“Are you from the Caribbean?” he said, turning his head slightly.

“Y-Yes.” Roxanne started at the sound of his raspy voice.

“I remember the islands,” he said simply, and turned back to the window. Roxanne waited, but that was all he said, so she crept from the room.

*

“He used to write crime stories,” Ethel said through a mouthful of bread and jam.

Roxanne sat nursing her coffee in the staff lounge. “So, what happened?”

“Don’t know, love,” she said, “except that he stopped writing mysteries and started to write other stories that nobody could understand.”

Roxanne downed the last of the coffee.

“Not one person comes to see him,” Ethel said. “He just sits there. His son dropped him off that first time. They didn’t say a word to each other.”

Ethel got up and poured more tea into her mug.

“That’s sad,” Roxanne said quietly.

“Don’t get too involved, lovey. First rule.”

“I hope you plan to rejoin the workforce before noon.”

They turned to find Madelaine Cunningham in the doorway. Although she was smiling, she was a formidable figure, standing there with sharp brown eyes magnified behind square-framed lenses.

Ethel shoved the last of the bread in her mouth and pushed back her chair. “C’mon, dear, before the dragon lady begins to spew fire.”

“I heard that,” Mrs. Cunningham said from halfway down the hall.

Roxanne hurried behind Ethel’s waddling form.

*

“What’s that you reading?”

Roxanne looked up to find Asha in the doorway, still wearing the apron from the restaurant down the street.

“Just something I got from the library. What’s up?” She put aside the book, The Other Side of Life by Harold Smith and sat up.

“You wouldn’t believe what I saw downstairs.” Asha sat on the bed beside Roxanne, grinning.

“What?”

“Miss Carmen’s got a man in the kitchen,” Asha threw back her head, clapping her hands as she laughed. “You should have seen her face when I walked in. I think I interrupted something.”

Roxanne chuckled. “I can’t believe I didn’t hear anything.”

“They were standing close like they were kissing. When I walk in, she pushes him away like a schoolgirl in the boy’s bathroom.”

“No wonder I’ve not had to hear her stories, recently,” Roxanne said, shaking her head.

“That’s not the shocking thing.”

“They were naked?”

Asha laughed again, patting her dark skin with the apron.

“He’s Indian.”

“Miss Carmen?”

“I know. Shocking!”

“Stranger things have happened.”

Roxanne was still shaking her head as Asha walked back to her room.

She lay back and picked up the book again. Ethel’s warning about not getting involved had only piqued her interest more and she’d headed to the public library to find out all she could about Harold Smith. There was precious little, only that he was born in Brixton, educated at Oxford, had one child in a brief marriage to a seamstress, Mavis Thornton, enjoyed some acclaim with the Inspector Radcliffe series, but became a recluse in 1982 after the poor public reception of his more serious fiction. She’d never cared much for crime thrillers, so had panned the twenty-four Radcliffe books for his last novel about an old man’s solitary journey across the Atlantic Ocean. She had begun reading it on the train, but found it a difficult read with its dense paragraphs and difficult vocabulary. Yet, the thought of him sitting slouched by the window buoyed her.

She pulled the red bookmark from chapter five, then was suddenly doused in darkness. She heard a bump in the next room and Asha’s angry mutterings in Swahili. She guessed they were very bad words.

A finger of light travelled into Roxanne’s room and Asha was standing there in bra and shorts, shining a pen flashlight.

“She forgot to feed the meter?” Roxanne asked.

“I swear, one of these days – ” Asha began.

“Sorry, loves.” The singsong voice echoed up the stairs. “I’ll take care of it.”

Asha shone the penlight on the posters behind Roxanne.

“Where’s that?”

“It’s Blue Lagoon in Portland,” Roxanne said. “I can’t believe all the places I haven’t been in my own country.”

“I know what you mean,” Asha said. “When I went home last year, I travelled all over Nairobi because I had never left my village before coming here.”

The lights came back on.

“That was quick,” Roxanne said, picking up the book again.

“No doubt thanks to our Indian friend,” Asha said, heading back to her room.

*

When Roxanne had a free moment before the end of her shift, she poked her head into Smith’s room. He was bent over his bed.

“Mr. Smith, are you okay?”

He looked up toward the door but not directly at her.

“I… I…” How to begin? She struggled to get out the words. Having read his novel, she now saw him as someone with great intelligence and feeling. In the end, she’d been won over by the story and the main character’s sheer gumption out there on the lonely seas.

“My grandfather used to work on a boat when he was young,” she offered.

He looked away and climbed into bed. She began to walk away, then stopped.

“I used to love those trips to Old Harbour Bay too,” she said. “Have you ever been to Jamaica?”

He looked up again and smiled slightly. From his picture on the dust jacket he must have been handsome once. Now, his face was a map of ridges and ravines, his bushy eyebrows and whiskers like muddy grey rushes.

“I went to Cuba once and to Trinidad,” he rasped.

Roxanne smiled.

“Papa Jenkins always told us he would sail to Cuba before he died.”

She brought the volume from behind her back.

“I tried to buy it, but they said it was out of print,” she apologized. “I never thought I’d like a book about a stubborn old man and his dream to see the world.”

He looked at the book. Then, he cocked his head and regarded her thoughtfully. “Do you think you could walk with me out to those willows outside? I figured that since I’ve seen them so much from this window, I should see them up close. My eyes don’t work as well as they used to.”

Roxanne took his left hand and he hobbled along with his right hand on his walker.

“So did he?” he said when they were outside.

“Who?”

“This Papa Jenkins.”

“No. He died this year in his home in Red Ground.”

“That’s a pity,” he said, “but it’s just as well. A man can go mad if he finds that achieving his dream is not at all what he expected.”

*

“That’s the third time this week you stayed overtime, Roxanne,” Ethel said, pulling on her jacket. “You know Cunningham will keel over before she pays you one extra cent, right?”

Roxanne put the towels on the top shelf of the closet and closed the door.

“I’m not doing it for the money, Ethel. I think I’m helping him.”

Ethel was shaking her head. “Take it from me, love, it’s always best to have some distance.”

“Why d’you say that?” Roxanne asked. “I mean, nobody ever comes see him. What’s the harm in that?”

Ethel put her large purse over her shoulder and regarded Roxanne for a moment.

“You seem determined to find out for yourself, dearie. Well, see you tomorrow. Don’t let Cunningham get used to seeing you leave late. You’ll never get back to your original time.”

Ethel could really be annoying. Why was she going on like this? Her words ate away at the sense of usefulness Roxanne had nurtured over the past two weeks. She had enjoyed her little chats with Harold. It gave her a good feeling to see him open up.

“You have a curious sense of humour,” he said when she’d found a topless page three girl from a 1978 newspaper in the main hall. She said she’d been tempted to post it on the bulletin board with a “Have You Seen My Owner” tag, just to see who would claim it when no one was around.

He had harrumphed in a way that she now realized wasn’t annoyance but wry amusement.

“I guarantee by eight o’clock, someone will have taken it. I think is Lester own from Room 40,” Roxanne offered. “He’s been known to strip naked and wait for one of the female assistants to find him like that and then ask if she want ‘sugar’.”

“So, you think we are dead already, so why bother? You know it could very well be someone’s wife here.”

“I suppose so. The mystery of the page three girl,” Roxanne had said, chuckling.

Their conversations had been like that, light and focused on his opinions of other residents and Roxanne’s recollections of digging yam hills with Papa Jenkins.

One day, she brought in the third volume of the Inspector Radcliffe series and put it on the chair by his bed.

“I told you not to bring those in here,” he grumbled.

“Don’t you miss writing?” she asked.

“That was another time. I don’t have much use for stories these days.”

Roxanne sat down and flipped through the library copy. “Well, I can tell you now that I don’t like who-done-its but this… this was… clever.”

Harold had been harrumphing and Roxanne felt that this time it was in annoyance, but she decided to press on.

“You sound like my old school master,” he said.

“Harold, why don’t you want to talk about this adorable little girl in the photograph?”

Harold closed his eyes and fell silent.

“Okay then, Harold. I’ll see you tomorrow. You should try to mingle with the others in the rec room. You’re not a prisoner, you know. Stanley down the hall plays chess and he’s always tryin’ to show off.”

“Call me ‘Harry’,” he said.

Roxanne smiled.

“Ok, Harry, I’ll see you.” She looked back at him. He appeared to be dozing.

As she closed the door, she glimpsed him open his eyes, reach for the photograph, and stroke the little face with a weathered hand.

*

Back in the apartment, pandemonium had broken out. Miss Carmen was sweeping up what sounded like broken glass in the kitchen, and Fiona was trying to get a curious brown stain out of a chair cushion.

“She was trying to make something for her Raj,” Fiona whispered.

“Oh?” Roxanne was already heading for the staircase.

“Then, he called and said he was going back to his wife.”

Roxanne stopped and looked back. She never thought she would actually feel anything but irritation for the woman. Now, she felt a faint prick of pity.

She continued up the stairs.

“Wait! We’re going on a trip to Oxford this weekend. You want to tag along?”

“I was going to bring Harry some gizzada.”

“Huh?”

“It’s a pastry we make in Jamaica – a dough shell shaped like a starfish, well, a starfish with several legs, with a coconut centre –”

“Harry? You mean the old guy at the nursing home you keep talking about? I thought you weren’t working this weekend.”

“I’m not. I just want to show him something my granny taught me to make. We were talking about it the other day.”

“You really hang around that place too much, Roxie. You need to meet some people your own age. Where’s the secret lover?” Fiona laughed.

“Why you think I need a man? All man do is get you in trouble.” Roxanne laughed, realising how easily her grandmother’s words had fallen from her mouth.

“Saturday. Eight o’clock. Meet me downstairs,” Fiona said, smiling.

*

How had she let herself be talked into this? The last time she’d been with Fiona and her group was on the tour of Leadenhall Market where scenes from Harry Potter had been filmed. This time, Fiona had brought along a fellow senior she was seeing, Barnaby Collingsworth the third. Asha had been inveigled into tagging along, too, and on the hourlong journey to Oxford she wondered to Roxanne why Fiona had insisted they come. It was so clearly Fiona and Barnaby’s outing.

They didn’t even get to sit together. Roxanne watched the twosome chattering at the front of the bus. Why hadn’t she just made those gizzadas and taken them to Harold? Barnaby had been pleasant enough, and she couldn’t say she disapproved of how Fiona’s face lit up as the two chatted.

Now, she stood squinting at the little map she’d gotten from a bookstore, her cellphone long dead from all the web surfing on the bus.

Perhaps she should retrace her steps. Oxford had not been what she expected, save the old gothic buildings. Along almost every street, modern shops were squeezed in between them. She had been delighted to find a market that sold saltfish, scotch-bonnet pepper sauce, dried sorrel and tins of ackee imported from Jamaica. It was the crush of tourists she had not expected. Every second person she asked how to get back to the main street would brandish their own little map.

She’d better not stray too far in case the others came back for her. She was at the Canterbury Gate entrance of Christ Church. She would check out the picture gallery nearby while she waited.

Since she’d come, she had not ventured much outside London. She did not have what her father said were the wandering feet of her mother. But then she hardly knew her mother, had only one clear memory of her.

She remembered eating stewed jimbilines and running out into the rain with her, squishing water through galoshes while her father predicted they would both get ringworm and end up at the public hospital. Roxanne would close her eyes and see the jimbilines, brown and sticky and her mother’s wide beautiful mouth, laughing and laughing.

Then she was gone, succumbed to pneumonia. Just like that. Roxanne was carted off to his parents’ farm in Red Ground. She’d been sure then, at five, that she was to blame, that this frolic in the rain had killed her mother, not knowing about her mother’s weak immune system.

As Roxanne entered the little gallery, a woman took her bag and the two-pound coin payment.

“No cameras. No touching, please,” the woman said in what Roxanne now recognized as a Geordie accent.

Why did the women in these paintings look so stolid and sickly, whether wrapped in bundles of fabric or exposing milky round bodies? They were nothing like the market women back home in Liguanea, big brown women in colourful batiks, mouths bright and bellowing.

“Beautiful, isn’t it?”

Roxanne turned to see a tall white man standing beside her.

Roxanne looked back at the painting of three figures, two women and a monk-like figure, the women both reaching to touch a baby.

“The Marriage of St. Catherine – said to be painted by Paolo Vernese in the sixteenth century,” the man said, cleaning his glasses on his shirt.

“Is okay, I suppose.” Roxanne looked at the women again, noting the same pallid, sombre look.

“Tough critic,” the man said, laughing lightly.

Roxanne glanced back at him, noting the way the glasses highlighted his intense grey stare.

“Are you a tour guide?”

“Oh no. I teach over at Pembroke College. I just like coming here sometimes.”

She looked at him, sceptical; he looked no older than she was – twenty-five.

“Where are you from?”

She sighed inwardly. The question so often led to some stranger’s declaration that he or she had visited her country. She did not care to know another foreigner had seen parts of her country she had not.

“Jamaica,” she said walking over to the other painting. The man followed.

“I thought so,” he said. “I always liked that accent. As an undergrad, I went there to St. Ann to study ferns.”

Roxanne smiled despite herself. Such a claim she had never heard before, but she pretended to look intently at the portrait of a woman staring in alarm out of the frame. Both she and the painted woman seeming to share the same unease, but she had paid her two pounds and intended to see every piece in this maze-like little gallery.

Finally, when he nodded at her and walked to the next room, Roxanne let out a little breath she hadn’t realized she was holding.

She had better check for Fiona and the others. She collected her bag and came out of the gallery and looked around the courtyard to see if she could spot them. She wished she had written down their numbers instead of storing them in her useless phone, then at least she could find a payphone or a bistro willing to let her use the phone.

She sat on a bench near the gate before looking across and catching the eye of the man she had seen earlier. He was smoking a cigarette and Roxanne groaned when he dropped the butt, crushed it under his heel and came over. She reached into her bag and pulled out the next volume of the Inspector Radcliffe books she’d begun reading that morning.

“Hi again,” he said.

“Hi,” she said, just glancing at him.

“I’m Jeremy,” he said, holding out a hand.

“Roxanne,” she said, shaking his hand briefly and beginning to read her book.

“Oh, ‘Roxanne’, like that song by The Police?” He sat down beside her.

“The Police?” Roxanne turned over a page she had not read. She would give Fiona and the others half an hour and then she would take a bus back to London without them.

“You know, the song ‘Roxanne’,” he said, breaking into a few bars of the song: “Roxanne, you don’t have to put on the red light. Those days are over. You don’t have to sell your body to the nigh –”

“So, Roxanne is a whore?” she interrupted, pleased he’d gone so red. She laughed as he fumbled an apology.

“You like Harold Smith?” he asked, breaking the silence.

“What?”

He was pointing at the book.

“Oh… yes.”

“Haven’t seen those in ages. Met him once.”

Roxanne looked up.

“You have?”

“Yes. As a kid, at a book signing in the eighties. I remember thinking he was mean-looking for someone whose books always made me laugh.”

Roxanne closed the book, debating whether she should say she knew him.

The man took off his glasses and ran a hand through his hair. There was something interesting about his profile she had to admit.

“Sad what happened to his daughter-in-law and granddaughter,” he said.

“What’s that?” Roxanne asked, the book forgotten in her lap.

“I remember seeing something in one of the papers,” he said. “It was a little story. I only remember it because I thought it a shame they stuck it right next to the obituaries when he was such a big deal before.”

Roxanne wished he would just get on with telling her what she had been trying to prise out of Harold for the past few weeks.

“Said it was his fault. Some said he’d been sloshed out of his mind before he got behind the wheel,” Jeremy said. “The little girl died instantly when he slammed into a tree, just five yards from his house. The daughter-in-law died in the ambulance.”

“How long ago was this?”

“Eight, ten months ago,” Jeremy said. “Such a shame. The little girl was only four.”

Roxanne looked back at the book, studying the black and white photo of the younger Harold Smith.

“I’ve met him,” she said. “I can’t imagine how – ”

“You have? Recently?” Jeremy asked.