Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

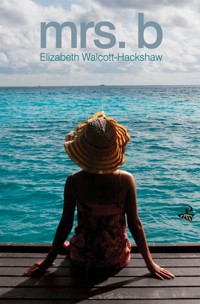

This novel, loosely inspired by Flaubert's Madame Bovary, focuses on the life of an upper middle class family in modern day Trinidad. The island, independent since 1962, still struggles with its multiethnic and multicultural complexities, and is fraught with corruption and violence. The heroine, Mrs. B (Marie Elena Butcher), is fast approaching 50. In her mid-life she is forced to admit that neither Ruthie, her daughter, nor her marriage to Charles Butcher, has met her expectations of being both a mother and a wife. Haunted by an affair with her husband's best friend, above all Mrs. B knows that she has disappointed herself. Much like Flaubert's heroine, Mrs. B's life is based on longing for what can never be realized and by an inability to adapt to the pressures of her own bourgeois society. Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw is a Senior Lecturer in French and Francophone Literatures, The University of the West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago. She has published various academic titles and her first collection of short stories was published in 2007. This book is also available as a eBook. Buy it from Amazon here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 344

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ELIZABETH WALCOTT-HACKSHAW

MRS. B

A NOVEL

ALSO BY ELIZABETH WALCOTT-HACKSHAW

Fiction

Four Taxis Facing North

Edited

With Nicole Roberts, Nicole and Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw, Border Crossings: A Trilingual Anthology of Caribbean Women Writers.

With Martin Munro, Echoes of the Haitian Revolution: 1804-2004.

With Martin Munro, Reinterpreting the Haitian Revolution and its Cultural Aftershocks (1804-2004).

First published in Great Britain in 2014Peepal Tree Press Ltd17 King’s AvenueLeeds LS6 1QSEngland

© 2014 Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw

ISBN13 (Kindle): 9781845232900ISBN13 (EPUB): 9781845232894ISBN13 (Print): 9781845232313

All rights reservedNo part of this publication may bereproduced or transmitted in any formwithout permission

The poem quoted on page 34 is “Love after Love” by Derek Walcott from Sea Grapes (1976)

CONTENTS

PART ONE

Chapter One: Arrivals, Trinidad, June 2009

Chapter Two: Home Sweet Home

Chapter Three: Bad Behaviour

Chapter Four: Mornings

Chapter Five: News

Chapter Six: Fine Wine

Chapter Seven: Trophies

PART TWO

Chapter One: Ants, Trinidad January 2010

Chapter Two: Poolside

Chapter Three: Mendacity

Chapter Four: Translations

Chapter Five: Gifts

Chapter Six: Crimes

PART THREE

Chapter One: Housekeeping

Chapter Two: Contagion

Chapter Three: Honour Thy Father and Mother

Chapter Four: Down-the-Islands

Chapter Five: Sunday

Chapter Six: Departures, Trinidad July 2010

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONEARRIVALS – TRINIDAD JUNE 2009

On the day that Ruthie returned home, six people were killed in the beautiful Valencia Valley. A popular pigtail vendor was amongst the six. According to police reports, Mr. Phillip Michael Beharry, 54, was shot in front of his barbecue pit at 6 pm on the evening of June 19th, Labour Day. It was alleged that the shooting was an act of revenge since Mr. Beharry had apparently been involved in an altercation with a young man the previous evening at “The Den”, a bar opposite Beharry’s pigtail outlet. The young man allegedly returned the following evening and shot Beharry three times in the head and once in the stomach. On arrival at the Southern Presbyterian Community Hospital, Mr. Phillip Michael Beharry, popular barbecued pigtail owner, was pronounced dead.

*

Charles had read the article on Beharry earlier that morning. The seven o’clock radio news was giving the story a longer life than most murders on the island, but it had nothing to do with Beharry himself; Beharry was murder number 360, doubling the murder toll on the same date from the previous year. 360 murdered in six months; this was an island record. Beharry’s biography even took up more time than the slight mention given to Uriah Buzz Butler and his famous protest march on June 19th 1937. Charles’s father had been a great fan of Butler and had spoken to his young son of Butler’s courage. Charles remembered little of what his father had said to him but he’d liked the name “Buzz Butler”.

Charles was still trying to get the football score. He had missed the sports report, and now it was only the weather forecast for the following day. He almost knew it by heart: “…waves up to two metres in open water, one point five in sheltered areas…” The only numbers that mattered was the result of the USA – Brazil match at the Confederations Cup in South Africa, on which he’d had a bet with his good buddy, Chow. Charles was about to complain to his wife that he was tired of the toll number on the front page of every newspaper every morning, as though there was nothing else happening in the damn country, or around the world, but he said nothing and consoled himself with the idea of finding the score on the FIFA website later that evening, or maybe sneaking a call to Chow at the airport. He didn’t dare to take his eyes off the road for even a second (the carnage on the roads competed with the murder toll) but he managed to glance across at his wife at a red traffic light. She looked far away, her thoughts no doubt with their daughter who was flying in that evening.

“We’ll be late,” she said, breaking away from the trance.

“We have time; the flight doesn’t get in until eight.”

“I was thinking about her name. She’s always hated her name. ‘Why did you call me Ruth? It’s such an ugly name.’ Remember she used to say that all the time in primary school, in high school as well. I can’t remember why we chose Ruth instead of something prettier, like Nicole or even Nina. Marie Claire Nicole Butcher. But then we still had to deal with your hatchet of a name. Isn’t that right, Mr. Butcher?” Mrs. B tried to force a smile but Charles knew she wasn’t joking. It was why she was known as Mrs. B and never Mrs. Butcher, and she was the one who’d insisted on Ruth, a name she had found in a novel she was reading at the time. Charles knew better than to say any of this, not now, not tonight, and luckily she didn’t demand an answer or talk again until they reached the airport car park at 7:30 pm.

“Remember not to say anything about Boston,” she said after closing the car door in the parking lot.

“What would I say, Elena?”

She didn’t reply, just kept walking a step or two ahead of her husband, quick short steps, high heels click click on the paved ground, her black dress swishing slightly, enhancing her neat figure and small waist. Charles wanted to tell her that she looked lovely, that she should relax, that everything would be okay with Ruthie. April was April. This was June; it was over now; she was coming home, she was better. But he just followed his wife mutely, trying to tuck his shirt into khaki trousers that were too tight.

The night before they had dinner with friends who toasted Ruthie’s return. No one mentioned what had happened during the spring break, though they all knew at least part of the story – the part about the nervous breakdown. They congratulated Mrs. B on having such a brilliant daughter, graduating summa cum laude no less. They reminded Mrs. B of the fabulous party she’d had for Ruthie after the Open Scholarship award was announced. On that evening everything shone, except Ruthie herself, who never wanted the attention. Mrs. B had invited fifty guests to the party on the verandah of their sprawling five-acre home in the valley: waiters, waitresses, champagne, samosas, smoked salmon, dim sum, shrimp, sushi. The front lawn was lit with tall bamboo torches; heliconias, tall red gingers and blood-red anthuriums filled huge clay pots on the verandah. Everything seemed perfect and even the two mosaic dolphins at the bottom of the pool seemed to smile with pride. Mrs. B, elegant and gracious, greeted each guest warmly, as though they were the most important person to enter her home. This was four years ago. So much had happened since then.

Ruthie had a few friends there. She didn’t surround herself with a troupe like her mother, didn’t like too many people around her. Though she was not a head-turner like her mother, Ruthie’s face could pull you in the more you looked, but she seldom smiled and usually had a serious look, as though she was resisting her prettiness. When people complimented her light brown eyes that seemed to sparkle against her olive skin, she barely acknowledged the compliment. Ruthie was not impolite, always said “Uncle this” or “Auntie that”, but she was not what her Martinican aunts would call souriante. Ruthie just looked as though she didn’t see the point of the perpetual grin that most of her mother’s friends always wore, like their lipstick. Ruthie did well in school, she had a good memory, one that could help her pass exams, help her cram – that was her true talent – so she won the end of term prizes, moved up easily from one standard to the other, crossed from one’s Dean’s list to another, but always without passion or pride. She knew she was bright but she certainly wasn’t the genius her mother claimed she was; all the light shining on her made Ruthie want to disappear. Mainly she felt like a fraud.

*

On that Labour Day evening, Ruthie was barely showing, but her face betrayed the anxiety she was trying to hide. From the plane, across the tarmac, into the cold building, feeling nauseous, she made her way through the long immigration lines (no stopping at duty free for gifts); picked up her baggage; lined up (nothing to declare) to emerge from the no man’s land between Custom’s officer and country, between what she left behind and what she brought home.

She walked out from the stale, air-conditioned, suitcase-smelling room into the thick hot island air to face the exhaust fumes of idling car engines. No more the broad Bostonian “paark the caar in Haarvard yaard”, but Trinidadian sing-song, up and down intonations; a “Taxi Miss” here, a “Taxi Miss” there, a crowd bunched together looking wary and hopeful, as each new traveller emerged from those magic doors, to face whatever it meant to be home.

Ruthie later claimed she had no idea that she had smuggled a baby (smuggled was the word she used) through the Customs, but Mrs. B couldn’t believe that her daughter didn’t know. She could not bring herself to say her daughter was a liar, but was unable to stop herself thinking that more trouble had arrived with her daughter, and that soon all her friends would know. Later, Mrs. B confided in confidence to her dear friends Jackie and Kathy, who passed on the news until everyone knew, but pretended that they didn’t. When Ruthie really started to show, no one was surprised, although they all pretended that they were.

*

Mrs. B nudged her way to the front of the crowd at the exit doors. She wanted to see what condition Ruthie was in. Charles had not accompanied her to Boston two months before; his excuse was the business. Charles’ cowardice no longer surprised her; she’d had to deal with many stressful, sad, even tragic incidents throughout their marriage without him, although this time it did seem strange since he seldom hid behind the excuse of business when it involved Ruthie.

April would go down as one of the worst months in Mrs. B’s life, cruel in every way. Boston was still very cold and Ruthie’s attitude towards her even colder. Ruthie was distant, like a stranger; she barely spoke to anyone in the psychiatric clinic. The day Mrs. B arrived in Boston she visited Ruthie’s roommate, Alice, who gave her the entire story. Alice had found Ruthie on the floor of their bathroom at four o’clock in the afternoon. Alice, short, stocky, effusive, Jewish, insisted on describing the unnatural position of Ruthie’s body which had made her think that Ruthie was dead. The vomit had streaks of blood in it, a thin watery string flowed out of Ruthie’s mouth, and the floor was slimy, the empty bottles of pills right there. She had puked in Ruthie’s vomit before she called the concierge, who called the security guard for the building. Mrs. B did not want any more details, but Alice seemed to need the repetition, for she described this scene several times during Mrs. B’s stay in Boston.

Mrs. B tried hard to erase the image of her daughter on the bathroom floor, with the horrible mess everywhere and felt irritated, embarrassed and ashamed that it was her daughter who had collapsed in front of everyone. She felt even more ashamed for feeling ashamed. Still, she was grateful to this chatty friend who had saved her daughter from God knows what. “Thank you, Alice,” Mrs. B said, and had Alice been Caribbean and not American, Mrs. B would have hugged her there and then, but instead she took Alice’s hand and held it in her own.

*

As she left the safety of the airport, Ruthie suddenly wanted to vomit. Her stomach was churning around a mixture of guilt, anger and embarrassment. Then it hit her worse than anything she had been through in recent months – and God knows she had been through a lot – it hit her like a slap from an old boyfriend, or a fall on hard ice: she still had feelings for the Professor, still felt something for le loup – the code name used by her dear friend Eddy.

Eddy was one of the few American friends she had made and cared about during her time in Boston; from the first time they spoke in an English Literature class, she trusted him instinctively – which surprised her because trust did not come to her naturally. When she found out that Eddy was gay she loved him even more; there would be no pressure. Eddy had helped her pack up in the last few days, getting her ready to leave Boston, getting her ready to leave le loup behind. Now, just when Ruthie thought she had finally escaped, the old feelings re-emerged, threatening to spoil the composure she had managed for her return home.

But now, here – the reunion with her parents imminent – she had to pull herself together. She could not re-enter this life looking as sick as she felt; she took deep breaths, hoping to suppress the desire to vomit the horrible, tasteless curry she’d had on the plane. She moved towards her parents without really seeing them. She thought she saw her father’s full head of greying hair towering over most of the people, then suddenly he disappeared and she sensed that her mother was close by because she smelled her oppressive perfume, the one she had always worn since Ruthie could remember. Then her mother appeared, trim as ever, black wrap dress, shiny dark brown hair cut just above the shoulders, deep wine lipstick on her light macadamia-coloured skin (all the women on her mother’s side had this colour, except Ruthie herself who was darker) moistened with her Lancôme, not a blemish, still looking lovely, even in her late forties.

“Sweetie, let me take that,” she said, kissing both of Ruthie’s cheeks, relieving Ruthie of her carry-on bag before she had a chance to respond, looking carefully at her daughter’s face for any signs of mental instability.

“Taxi, Miss?” An Indian taxi driver hovered, repeating the question.

“No, no, thank you, we have a car.” Mrs. B replied curtly. Where the hell was Charles? “How was the trip? Your father must have spotted you and gone to bring the car around. I never understand how he just disappears like that without saying a word…”

Her mother continued to talk, complaining about her father’s disappearing acts; Ruthie didn’t really focus on what she was saying. She was used to her mother’s nervous chatter; it was always her way of dealing with uncomfortable situations, and this was obviously one. Ruthie’s nausea had passed for the moment, but it was replaced by a lightheaded feeling, even a lightness of being, allowing her to float above the entire scene; she looked down on an amazing aerial view of the airport, the people, the cars and the highway leading into the lights of Port-of-Spain. She could even see the Stollmeyer’s Castle facing the Queen’s Park Savannah, the Queen’s Royal College, the Archbishop’s residence, but then she fell and landed right back on the pavement at the airport in front of her mother, suddenly very aware that she had left Boston and her Professor.

*

Mrs. B, who’d had to cultivate her elegance, studying her mother Simone’s style very closely, simply did not understand how someone blessed with a long slim torso, ballerina legs, and such a graceful neck simply refused to acknowledge or take advantage of her good fortune. What a waste of a waist was all Mrs. B could think of as she examined her daughter’s travelling attire. Ruthie looked so careless in the way she presented herself to the world – the untidiness of her adopted American lifestyle, the horrible hemp bag; that messy American-ness had become part of her look and it irritated Mrs. B. She didn’t see herself as old fashioned, she’d had to accept the notion of being middle-aged, but what was wrong with wanting to present oneself in the best way possible. “Elegance,” her mother Simone would say, “is the best defence.” Mrs. B was well aware of how little elegance mattered to Charles, but she still strove for it and now she had to admit that for Ruthie, like her father, it didn’t matter.

*

Seeing Ruthie again and remembering all that she had been through in April took Mrs. B back to another sad time in her life, of another arrival coupled with a departure. It was when Mrs. B was a young girl of eight going on nine, when she was called Marie Elena Roumain. In those days she played a game with God. It came to be called the Ceiling Game. The game started soon after she moved into her Aunt Claire’s three-bedroom bungalow, in an area where all the houses looked the same – a box with a grey galvanized roof, a low white front wall, neatly potted plants that lined a short, narrow driveway that led to a narrower door into a small kitchen, just off the garage. Aunt Claire’s small garden was no different from the others, except for the two swans and the white ceramic mother duck with four white ducklings that she had carefully placed just below the grotto that housed Mary, Joseph, baby Jesus, two oxen and three wise men. Marie Elena’s mother, her Aunt Claire’s one and only sister, Simone, used to say: “Clarita sweetie, I love you to death but I swear to God I think you may actually have the worst taste in the world.” Then she would laugh, because from birth Simone had been given a powerful yet playful laugh; it gave her a free pass to speak her mind, saying exactly what she felt, when she felt it, seldom caring or even noticing who she slashed along the way. At the time, Marie Elena, the young Mrs. B, had not yet felt her mother’s sting, but she had sensed that Aunt Claire avoided her sister as much as possible.

Her parents left the eight-year-old Marie Elena at Aunt Claire’s house for two years. There were visits during those two years, and vacations when Elena would spend a month here with her father, Michael, or there with Simone. Sometimes Elena travelled to big cities like London or New York or other islands like Grenada, Jamaica, St Thomas or Barbuda; sometimes she spent weeks in a fancy hotel, and hours on planes being sent from the father to the mother, parcelled over from one air hostess to another. But after all those trips here, there and everywhere, Marie Elena would end up in the house on Hibiscus Drive with Auntie Claire.

Under her bed in an old shoe box where she was supposed to keep her white shoes for Sunday mass, Marie Elena put her mementos from her travels: postcards of couples lying on Grand Anse beach in Grenada; palm trees and sunsets in St Lucia; tiny shells from Martinique; a dime and a quarter snatched from a saucer; a pound note pressed in her palm by a stranger; a miniature Statue of Liberty, a tiny bright red double-decker bus, museum tickets, and the cap of the Coca Cola bottle from the day she shared a gigantic hot dog and two Cokes with her mother, sitting on a bench in Central Park. Marie Elena tried to collect memories as well, but these faded fast. So, from an early age, the future Mrs. B learned to hide what she treasured most.

There were times when Elena got very angry, berated her little self for what she should have remembered. In the days and months after her parents left her at Auntie Claire’s, she often tried to recall the details of the morning they brought her to the house on Hibiscus Drive. Sometimes she saw her mother dressed up, laughing her strange, crazy, powerful laugh; sometimes she thought she saw her mother shed a tear; sometimes she saw her father in a dark suit trying his best not to look at her as he put down boxes of books, dolls and clothes in the tiny bedroom; sometimes she thought she saw her father smile. She thought she remembered her aunt standing like a thin, tall statue, barely breathing, holding her hand. When her parents drove away Elena remembered thinking that this would be the saddest part of her life, but she soon learned that life had many more days like this to offer.

In those days Marie Elena dreamed night and day of owning a city that was both island and metropolis, a big-city city like the ones she had visited with her parents. In these reveries she wasn’t just owner of the city, keeper of the keys, lady at the gate, she, Elena, was the city. Powerful enough to change a building and become a building herself, she could also become a hurricane, a landslide, topple people from buildings with an earthquake, kill an entire village with a tidal wave. She drew a world filled with countries called ELENA on the pages of old copy books. There were ELENA cities with towering skyscrapers, ELENA villages with houses floating on rivers, ELENA oceans with fleets of ships – places drawn over sums and spelling tests. Sometimes she would glue old newspaper cuttings over the drawings, stick on beads or pieces of old cloth. Other times she would take leaves from the bougainvillea and flowers from the hibiscus and glue them into her world. Inspired by the Alice in Wonderland pop-up book her mother had given her, Elena tried to make her world like Alice’s and for a while she was quite proud of what she had created. But even as God of her own world, with the power to build and destroy houses and families at will, her powers seemed to disappear when it came to her parents, so eventually Elena moved on to other things.

One of these was a promising friendship with God and his family. In church she had heard that everyone had a friend in Jesus, so Elena saw no reason why she and God, Jesus’s father, couldn’t be friends, and if Jesus was God and God was Jesus and the Father was the Son and the Holy Spirit, she really didn’t see a problem, the more the merrier. At eight years old, Elena got along very well with the Trinity, especially when they played games like the Ceiling Game. The rules were quite simple. If Elena managed to touch the ceiling in the hallway three times in a row, God or Jesus would have to grant her three wishes since three seemed to be their favourite number. Her strategy was usually to run as fast as she could, often without shoes (which she thought would make her lighter) stretch her arms above her head, and launch herself into the air, hoping that the tips of her fingers would graze the ceiling.

The ceiling wasn’t that high but she had yet to grow into the long, slender body she would inherit from Michael and Simone. She often succeeded in touching the ceiling twice in a row, but never quite made three times, at least this is what she remembered. Sometimes Aunt Claire would catch her at this game and in her quiet, gentle way would say that Elena should not run in the hallway since she could have a bad fall. Most of the time, Claire left Elena to her own devices. At that age, the young Mrs. B pretended to be as good as any other eight year old girl; she did her homework, made her bed, had good table manners, always said please, thank you, good morning and you’re welcome, went to piano lessons, did not fidget during Sunday morning Mass and always sat like a young lady. There was little for Aunt Claire to complain about.

Apart from the short vacations with her father or her mother, Elena lived in the house on Hibiscus Drive. Two years passed before she left her aunt to live mainly with her mother and occasionally with her father. By then, she had already fallen out in a big way with God, Jesus and the whole entourage. They with all their supreme powers, apparently could not protect her from a witch at school called Veronica and her young sorcière assistant, Monica, from a music teacher and from another creature whom Elena always kept nameless since he was nothing less than the devil on earth. With no God listening to her and monsters everywhere, her cities fell apart, and her powers began to fade like the old curtains in her Aunt Claire’s drawing room. Great expectations began to drip, drip, drip like the leaking tap at the back of her Aunt Claire’s house and she blamed everyone, but mostly her old friend God for all the leakage.

*

Aunt Claire was tall and thin, with the same macadamia-coloured skin as her sister. She was not glamorous, not as startlingly beautiful as Simone. If you ignored her slightly slanted, ink-coloured eyes, or the wideness of her smile, you might even think her pleasantly plain. It was true that she did not have the best taste when it came to what she wore or the furniture in her home; everything was functional, practical, neat and clean. She had lived alone for some years before her niece arrived, so perhaps she did not realize (or perhaps no longer cared) how plain she looked and how unadorned and simple her life had become. Everything had a place and there was a place for everything. She had folded and stacked her past carefully, leaving just a few spaces to slot in the future; her days were measured by ritual and routine: her morning ablutions, her prayers, her daily walk, her voluntary work at the church, her teaching and always her reading in the evening. It was this routine that made her sister Simone say that Elena would be a gift, a blessing to “poor, lonely Claire”, that her existence would suddenly have purpose and meaning. Simone was tempted to think “old maid”, but she resisted; Claire at thirty-three was only two years her senior.

Truth be told, Claire did not want to take care of Elena. She had no desire to raise a child – those painful feelings had long passed. But she was never as powerful as Simone, even though she was the elder; and though she thought she had shown outward signs of protest, Simone pretended not to notice. Simone drew her older sister in with all her charms, hypnotizing her with her sorrows, dangling the precious spirits of their dead parents and even speaking for them. “Wouldn’t they have wanted their granddaughter to have a peaceful place during these stormy times,” and then promising that Elena would only be there for a couple of months, not the two years that she had probably intended all along. It was not that Claire was weak with everyone; she had stood up to seemingly greater forces than her sister, but for reasons that she did not understand, Simone had managed to manipulate her ever since she could speak. Simone knew this and knew that Claire knew she knew this. The rules of the game had never changed.

*

During the day Claire was known simply as “Miss” to her third standard class at the Princess Margaret Primary School, conveniently located within walking distance from 623 Hibiscus Drive, where she had moved two years before Elena’s arrival. Claire had tried her best to find complete contentment in her teaching, trying to live for those little brown, third-standard faces that looked to their “Miss” for all the answers, but she had to admit that it was not enough and at times tremendously tedious. She would have preferred to spend her day in the room she called her library. A librarian was what she had dreamed of becoming – she had never wanted to be a teacher, but without the necessary qualifications she had been forced to settle for the job of “Miss”. As a librarian there would be fewer questions, definitely less noise and no more Miss. There would be no need to make small talk with the other teachers; she imagined all librarians sought the same solitude. She could barely control her ecstasy when she imagined herself surrounded by shelves and shelves of books; there was something she found on the second floor of the Port of Spain Public Library that she could not find even in church. But there was also the guilt that she felt at the thought of reading her favourite poems with Mary, Jesus and all the saints looking over her shoulder, and she had never missed Sunday Mass even though there were days when the early morning rain made her feel like lying in bed with Baudelaire. To others, Claire’s love of reading did not seem to go beyond the obvious – a romantic to the core, it allowed her to escape to another world, to be transported from an ordinary life to something better. It gave her the simple pleasure of being lost, of never noticing time passing because, more than anything, Claire wanted time to pass. She believed all the clichés about wounds being healed by the balm of time. Sometimes, though, Claire read in a way that others were less likely to deduce; sometimes what she felt could only be described as a frisson: discovering new words or following the patterns that the sentences made, seeing beauty in simplicity, complexity in that beauty, perfection in all its forms and shapes – page after page. Claire loved it all – no, it was more than love – it was pure adoration. There was another gratifying aspect to her reading; it was the only advantage, although slight, that she had over Simone, who had never been much of a reader.

As a child, Claire, like her father (another great reader, and the one who taught her, more than any teacher, how to read), read all the time, though her family was not sure that it was the best thing for someone as homely looking as Claire to fill her mind with false hopes and the Cinderella expectations that these books might give. Her old aunts feared that Claire would further lessen her chances of finding a good husband if her vocabulary continued to expand at such a quick pace. No man wanted a wife who seemed more intelligent than he. The old aunts lived in a perpetual state of anxiety about poor Claire’s future. It didn’t help when two Fathers of the parish came to the house one afternoon to have tea with the Roumain family that Claire was seen holding a Koran, (taken from her father’s library). Needless to say, the priests noticed, mentioned it to the old aunts, who in turn encouraged Claire’s father to be a little more vigilant about his daughter’s choice of reading material.

Indeed, the old aunts strongly urged Claire’s parents to censor her selection of books. Until then, Claire had been allowed to browse the shelves and select at will novels, poetry, plays, books on horticulture, agriculture, bird-watching, fishing and the history of the British Empire. Her parents had already removed unsuitable texts like the Kama Sutra, the Marquis de Sade and the banned poems of Baudelaire. After the Koran incident and the old aunts’ insidious nagging, a battle for righteousness, though not the war, was won. For a while it was salvation over education.

As a young girl, Claire also read to hide behind a book, shying away from questions, requests and social gatherings. Unlike Simone, who shone like a jewel in a crowd, Claire wanted to disappear. In those days Claire’s books were her only shields, though she learned that they could not protect her from the disappointment of a missed party because her family did not know the parents of the little girl or boy she liked, and they certainly could not protect her from the pain that an aunt or an uncle inflicted so casually with a cruel word or careless remark.

In her study, Claire arranged her books the way she wished she could have arranged her past life – carefully, thoughtfully, even with kindness, making sure that those with similar ideas, religious beliefs or experiences were grouped together; some kind of correspondence had to take place on her shelves. So instead of putting Madame Bovary with all the other 19th century French novels she had collected during her year in Paris, she thought that Emma should be next to Anna Karenina. With so much pain to share, the two women could comfort each other. Verlaine and Rimbaud, having endured such violent quarrels, could never be next to each other, so she put Rimbaud next to Ronsard, and Verlaine next to Watteau, a painter he admired. Baudelaire stayed away from Hugo and was placed next to another great, Shakespeare. Even if the two men were from different times Claire felt that they shared dark loves and battles of the soul.

But there was more; while reading shielded her from the outside, familiarity with her books guided her into other places. What Claire loved most was that she knew what to expect, she knew the plots by heart; there were no surprises. Claire could drop in and out, just like Alice in Wonderland; she could assume different roles at different parts of different books; she could become the heroine in one chapter or a less important character in another. It was ridiculous how many times she had reread Madame Bovary; just holding that book could take her into the back of the carriage with Leon or into the woods with Rodolphe. She knew what the kiss did to Emma. Claire could almost feel it, and once she actually held the page close to her lips that were parted ever so slightly, just the way she imagined Emma’s had been with Rodolphe that afternoon. Claire knew Emma better than any other character because in her own life she had met her own Leon and several Rodolphes.

What no-one knew about Claire’s reading was that the more times she read a book, the more emboldened she was to take liberties with the writer’s decisions; sometimes she would scribble passages in her notebook that changed the plots or parts of the story. She would have allowed Emma to be consoled by a kind priest, not the uncaring one in the book, but a new, charming character, who when Emma went into the church that day seeking guidance or some sort of solace, would seduce Emma back into the church with his intelligence, heightened sensibility and overpowering good looks.

Claire knew that the family was not happy that she lived alone, but it was the only way she could survive the brutalities committed against her so early on. She knew this aloneness made her seem a little odd, and even she wondered if living in these fantasies was a sign of some abnormality, but was she hurting anyone? And did anyone really care what she did with her time? So she enjoyed her invisibility more and more and kept these imaginings to herself. Everyone had secrets, even Simone.

So imagine Elena’s surprise the day she walked into Aunt Claire’s study for the first time. The small room was filled with books on every wall save one where there was a sofa, a lamp and two votives on a side table. The room had a strange smell; a mixture of hot chocolate, vetiver, vanilla and something else. It was a male smell.

CHAPTER TWOHOME SWEET HOME

Mrs. B had spent a lot of time, energy and money refurbishing the guest room for Ruthie’s arrival. She wanted Ruthie to have more space, more privacy and the guest room downstairs had a private bathroom. She knew that Ruthie didn’t like their new home in a gated community, the San Pedro Villas. In fact neither Mrs. B nor Charles had really become used to it; there were too many neighbours, too much gossip. They had never wanted to leave their five-acre home in the valley. Mrs. B still missed the white egrets on the lawn in the morning, the parrots flying home to the bamboo trees in the evening and their mini estate of oranges, grapefruits, avocados, mangoes and lime trees. In their last years in the valley, Mrs. B and her longtime gardener, Sammy, had grown a healthy kitchen garden of basil, thyme, rosemary and mint just off the kitchen porch. Only the herb garden had been transplanted, but now clay pots held the plants and the roots were no longer in the earth.

Their house in the valley had a verandah built to imitate the old colonial style; it wrapped around most of the ground floor and allowed an easy flow onto the soft Bermuda grass. Before Charles and Mrs. B built the house she had wanted to buy one of the older colonial estate homes, like the ones her family owned when she was a child, but Charles said this was impractical since restoring the homes she liked would have cost as much as constructing a new one. But she had managed, with Charles and their architect, to build a home with all the nostalgic details of her childhood: high wooden ceilings, tall doors, and wooden latticework along the edges of the roof.

During her first few months in San Pedro she had enjoyed the company of her neighbours – many of whom they knew from high school days – and the ability to see her close friends, who all lived nearby. But after a while she began to miss the things she had taken for granted in her old home; here in San Pedro the constant need to meet, greet and give daily updates on anything and everything began to irritate. A face seemed to appear the moment she stepped out of her townhouse door, or out of her car, or even when she sought some peace in her small backyard garden. In San Pedro, the custom of phoning before a visit seemed unnecessary especially since the neighbour lived only minutes away; walking in to someone’s front door and simply calling out “Hello” was the norm. After four years Mrs. B had grown tired of the place; she longed for the simple pleasure of walking to the edge of her old property and sitting on her favourite bench under the sprawling samaan tree just above the path that led down to the river.

Originally San Pedro seemed the best option: good location in the west, excellent neighbourhood, mall and grocery minutes away, with a view of the sea. Each unit had three bedrooms, three bathrooms and a powder room, a living area to the back that opened onto a small but thoughtfully landscaped garden with neat beds of ginger lilies, alamandas, and exotic ground cover. There were some tall, carefully pruned ficus and a few weeping willows at the edge of the compound. Separating side A from side B of the compound were nine royal palms that gave it an air of grandeur. It was the palms that had drawn Mrs. B and Charles to San Pedro.

But she couldn’t help making comparisons with the valley. On mornings in San Pedro, young twenty-something housewives left their babies with housekeepers who arrived in droves at the crack of dawn as their young employers went to work or the gym in their shiny new cars. In the afternoons Mrs. B would see the mothers once again, walking their little cherubs in fancy carriages around the compound. The fathers would come home in the evening, suited and tired. The sight of the young families affected Mrs. B with envy, nostalgia and an indescribable numbness. Besides the young couples, there were many like Mrs. B and Charles, a group of forty-somethings to fifty-somethings who had left much larger properties partly for the convenience but primarily for the security. San Pedro boasted the best guarded gated community in the west; whether this was true or not, it didn’t hurt that the family of one of the young Lebanese couples living there owned the security firm that guarded the compound. At night, guards patrolled with pit bulls; they were without them during the day, but always carried concealed weapons. Curled barbed wire atop the compound walls bordering the main street mostly deterred bandits from jumping over, though the previous Carnival season, two crackheads, or pipers, hazarded a jump, only to be welcomed by pit bulls, guns, batons and cricket bats.