8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

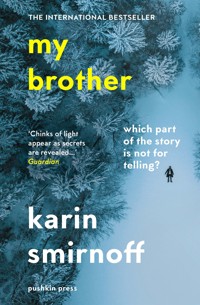

STEEPED IN DARKNESS, COMPLICITY AND FORGIVENESS, THIS BESTSELLING SCANDI NOIR IS FOR FANS OF LITERARY FICTION SUCH AS MY ABSOLUTE DARLING, A LITTLE LIFE AND THE DISCOMFORT OF EVENING A MAJOR BESTSELLEROPTIONED FOR TV BY THE PRODUCERS OF THE BRIDGESHORTLISTED FOR THE PRESTIGIOUS AUGUST PRIZETRANSLATED INTO ELEVEN LANGUAGES 'Well worth the read' GUARDIAN 'Bleak and beautiful rural noir' CRIMEREADS 'Perfect for fans of Scandi-noir dramas' CULTUREFLY ____________ Jana Kippo has returned to Smalånger to see her twin brother, Bror, still living in the small family farmhouse in the remote north of Sweden. Within the isolated community, secrets and lies have grown silently, undisturbed for years. Following the discovery of a young woman's body in the long grass behind the sawmill, the siblings, hooked by a childhood steeped in darkness, need to break free. But the truth cannot be found in other people's stories. The question is - can it be found anywhere? A literary noir of phenomenal power about the magnetic attraction of the wrong person, the brutality visited upon one human to another - and a rural community that stood by and did nothing ____________ FURTHER PRAISE FOR MY BROTHER 'Possesses the same melodramatic power as Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels' ETC 'A media sensation. . . remarkable' GP 'Brutal, colourful, carnal. . . Impossible to put down' Expressen 'A rare story-telling talent' Aftonbladet ____________ READERS LOVE MY BROTHER 'A powerful story, brilliantly translated' 'Rural and epic in landscape, deep and heart-breaking in loss, and truth' 'If you enjoyed The Discomfort of Evenings by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, I think you will enjoy this too!'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

3

my brother

karin smirnoff

Translated from the Swedish by Anna Paterson

pushkin press

5

far awa from the warld

Far awa in the ill pairt

Lost in the warld

I play my melodium

for the pyne in my saul

The bellow is broke

Broke is my soul

Far doun in th’ill pairt

Lost in the warld

—Helmer Grundström

6

CONTENTS

ONE

Iwent to see my brother. Took the bus along the efour down the coast and jumped off at the stop for the village. Then I set out to walk.

It snowed heavily. The road was disappearing under the drifts. Snowflakes tumbled into the low tops of my boots and my ankles froze as they did in childhood.

I would have thumbed a lift but no cars came. My brother’s house was a couple of kilometres away up a slope.

I sang songs by everttaube to distract myself. Our parents loved everttaube and then they died.

The wind slashed my coat. The top button was missing and snow was melting against my neck. I should’ve got there by now. The snow made the landscape anonymous. Had I even passed eskilbrännström’s yet. I speeded up. For as long as the ship stays afloat. Then Who said just you would be born.

A bundle forced itself forward through the snow fog. A huddled human shape straining against the wind. At first I couldn’t see if it was a man or a woman.

The wind swerved. The snowflakes were handsized. For a few seconds the figure wasn’t there but then the wind blew its hardest and in the eye of the storm I saw who it was.

It was no one I knew.

Some weather he said when he had come close and I nodded. He wanted to know where I was off to and I said kippofarm. 8

Then you must’ve taken the wrong turning at the crossroads he said through his scarf. You should’ve turned right. I’ll come with you he said.

I could only make out his nose and eyes between the scarf and the woolly cap. Tried to catch his eye but he kept looking ahead.

We turned even though the compass inside me still pointed the opposite way.

He offered me his gloves. It was a long time since I’d shared somebody’s gloves. I couldn’t get my head round having gone the wrong way. We turned and walked back. Facing the wind and bending over like children lost on the high fells.

He lived nearby and his name was john.

I’m jana I said. I’m going to visit my brother.

And your brother’s name is bror he said. I know who you are.

Where were you going I screamed to be heard above the wind. It was gaining strength.

Nowhere he screamed back. I just like the wild weather.

He pointed towards a track where faint footsteps were still showing in the snow. I live along there, not far. Let’s go to my house and warm up. Then you can start out again when the blizzard has died down.

I hesitated because I didn’t recognise him but I ought to have. Besides, I knew that the track led to eskilbrännström’s house.

Do you live in the deserted house I asked and he nodded.

I didn’t know one could live there. With your family or do you live alone.

It’s the kind of place where one can only live alone he said.

The wind was still whipping snow against my neck. My face had lost all sensation long ago. I followed him. 9

He kindled the fire in the stove and found a pink woollen blanket to spread over me where I sat on the kitchen sofa in my longjohns and top while my clothes were drying over a chair.

It’s from the ume valley asylum he said. When the loonies were moved out all the stuff was sold at auction.

There was something familiar about the room and I thought that maybe I had been there before. The kitchen was worn in a quiet, gentle way. Apart from the sofa there was an ancient folding table a few handmade västerbotten chairs a tall dresser and a ticking clock though it showed the wrong time.

So it seemed he lived there. Probably slept in the tall old pullout bed that I was sitting on with my legs dangling because my feet didn’t reach the floor.

Do you live in the kitchen I asked as I cupped my hands around the hot mug he handed me.

Yes mostly he replied. In the winter anyway. In the summer I sleep in the attic or in the bestroom.

That bestroom now I wondered and held on to a distant memory. Does it have a painted ceiling. He nodded slurping his coffee from a saucer with a lump of sugar between his teeth like old people do.

I saw the bestroom in my mind as it had been. A pair of yellow rubber boots on a black chest. A chest that wouldn’t open. And how I finally had set to work with a flattened iron bar I had found plunged into the ground as a border marker. I shoved the bar in between the lid and body of the chest and heaved until the lock snapped.

Twentyfive years later I couldn’t remember what was in that chest. Perhaps nothing more than stale air.

He asked do you know who my brother adam was. 10

I didn’t know.

We were playing in the hayloft he said. Vaulting off roofbeams and landing in the hay. Adam was the elder by a few years and always dared more than I did. It didn’t help however much I tried to push back at my fear.

Earlier that day he had stolen some cigarettes and asked if I wanted to try one. I didn’t want to come across like a baby so I reached out for one of his nofilter glens and stuck it in the corner of my mouth while my brother lit a match. We didn’t realise that I might choke on the smoke have a fit of coughing and drop my nofilterfag into the hay. Finding a lit cigarette in a haystack is in principle as hard as finding a needle.

The newmown hay might well have smothered the flame if we had left it alone but the more we kept rooting around the more oxygen got in and suddenly fires flared up around us.

I hurled myself down to the floor of the byre and ran out into the sunshine and the air with thick smoke trailing behind me. I ran across the yard and up towards the farmhouse to get help but turned back when I discovered adam wasn’t behind me.

I shouted his name. Through a narrow gap between the fire and the smoke I saw his arm hanging down over the edge of the hayloft.

The man fell silent and pulled himself together. Busied himself at the sink. Caught coffee grains on a kitchen cloth and tugged at his big black mane of wavy hair to get it out of the way. Looked at me and explained.

The most likely thing is that the smoke got to him. I moved the ladder and held my breath and climbed up to him as quickly as I could. Managed to grab hold of his arm and tried to haul him down but he was heavy and I wasn’t strong enough. 11

That’s how it happened. I wasn’t strong enough to rescue my brother. Wasn’t even aware that my hair was on fire. Only how smooth the skin was on adam’s already dead arm.

It was his boots you saw on the chest if you wondered.

Such a sad tale. Still he could have been lying.

I felt drowsy from the warmth from the stove and the hot coffee. I should’ve got dressed and carried on walking up the hill to my brother but my body felt listless and resisted going back out into the blizzard. I pulled my legs up and tried to work out what that smell was. It wasn’t nasty. I imagined some foreign places might smell like it. A foostie smell my mother would have said and perhaps it was just old dirt I was sniffing for like a dog on the trail. But however much I sniffed I couldn’t identify it.

You sleep here if you like he said. I can bed down on the floor or sleep on a chair. It was a pullout bed. I usually find it distasteful to be physically close to people I don’t know but offered to share it with him. It would be a tight fit.

He blew out the lamp. It was only then it struck me that the house had no electricity. A rare kind of silence filled the shadowy kitchen as the wind snow and cold fought on the other side of the singleglazed windows.

It wasn’t easy to sleep. Hours passed while we listened to each other’s breathing. I was nearest the room and one of my legs was resting on the hard edge of the bed. He was pressed against the back of the sofa. I sensed his body against mine even though we barely touched. And when he breathed out I breathed in his breaths as if we were stuck underwater sharing an oxygen cylinder.

My leg slid back down into the bed. His arm couldn’t hold out any longer and fell back into an easier place. When my hand slipped into his relaxed fist my mind found peace. 12

It was light when I woke and the room’s mood had changed from last night. The windows were framed by sunbleached curtains. Wear and tear had left small rips in the weave. On the window sills, crowds of potted geraniums were almost about to come out of their winterdoze.

John was already up and about. He had put new logs on the fire and added a couple of heaped spoonfuls to the coffee dregs from last night.

I watched him from my horizontal position. An orange lumberjack sweater was doing things at the worktop by the sink. When the sweater turned towards me I saw his face in daylight for the first time and couldn’t resist the impulse to look away.

Don’t worry he said I’m used to it.

He laid the table with coffee cups soft flatbread butter and västerbotten cheese. Looked at me smiling a little and hoped I had slept well. Settled down with his saucer and sugarlump.

What happened afterwards I asked. I mean after your brother died.

This time my gaze lingered to observe the burnt skin that stretched across one half of his face and covered it with ridges like furrows on a sandbank when the water has drained away.

After adam’s death everything changed. We used to be no different from other smallholders scraping a poor living from work on the land. Dad would take forestry jobs in the winter and go fishing in the summer. When dad was away adam was in charge. Not mum. Her usual place was a stool next to the workbench. She ate what was left on our plates. It wasn’t that she saw herself as a menial. She did what seemed right to her.

For a while he sat in silence with his eyes fixed on the memory. 13

Dad blamed me for adam’s death. Insisted I could have saved my brother. Because I had a harelip and was hard of hearing I was sent away to a school in örebro where they were supposed to be able to cure both cleft lips and deafness.

How old were you I asked for chronology’s sake.

Ten, almost eleven.

I dressed. Pulled my trousers over the longjohns. My socks and boots had dried. It was still snowing but only lightly. The sun was fighting to get out from behind the massed clouds. It might be a nice day.

A soft light fell on his face. I wanted to touch the burnt skin so that later I could shape the clay to look like it but thought the gesture might be misunderstood.

May I look in the bestroom before I go.

Feel free.

The room looked just as I remembered it. The ceiling was decorated in faded rustic patterns and the timber walls were splatter painted.

Even the chest was still there but not the boots.

The biggest difference was the set of large oil paintings. The canvases had simply been stapled onto the walls. Paintings like stage sets. Fire smoke faces grass sea body parts rubber boots and hands all so skilfully painted the effect was photographic.

Are these yours I asked and he nodded. I paint now and then.

Have you shown them to anyone but no he hadn’t I was the first to see them.

You can paint I told him stunned by what I saw. It affected me so much I had to move on. As I backed out of the room the canvases formed the background to john in the foreground with his damaged face and large head of black hair. 14

I didn’t see only the paintings I saw myself my brother my parents. And there mum came running. Screamed you must do something. Save him. Excited cattle were bellowing.

The horse was neighing kill kill.

John raised his hand meaning bye see you. I did the same. And when I had closed the door behind me I ran until there was no more oxygen to keep me running.

TWO

We were drinking whisky in bror’s kitchen. Or, not really. Bror drank whisky and I drank tea. He had lit a fire on the hearth. I did my best not to see the dirt and disorder. We were born just a few minutes apart and are alike in many ways. Especially in how we look. We are thin and gingery, with straggly unpigmented hair. We are so bleakly unremarkable that nobody used to remember either of us as somebody. Only as the twins.

Has something happened that made you come here he asked.

Nothing special I said my mind on the paintings in the bestroom. I had nothing to do over easter that’s all.

It had grown late. We went for a walk with the elkhound. By now the sky was clear and starry once more. The mutt tugged us along at a brisk pace. The thermometer had dropped to minus twelve and the snow was creaking underfoot. Past göranbäckström’s there were no more streetlamps but the light of the snow and the stars was enough.

We talked about what had happened here. Who had died. Who had fallen ill. About hunting ptarmigans in the hills and about a neighbour’s bitch that had been successfully mated. The kind of things you talk about in villages like smalånger. We did not touch on why emelie had left him or why our childhood home was decaying.

For a second night I slept in a pullout bed. Too tired to undress, I used my coat as a blanket and fell asleep instantly. 16

In the morning I put on rubber gloves, filled a bucket with soapy water and systematically worked my way through room after room. That afternoon, there was a pile of rubbish bags on the steps. Bags full of beer cans pizza cartons dead potted plants newspapers food long past its best empty dog food cans bottles of spirits broken ornaments cracked picture frames and a whole lot of women’s clothes slashed to ribbons.

Everyone is good at something or so the saying goes. It pleased me to see the veined wood of the soapy boards and the glowing lime paint of the wooden cladding. It pleased me when boiling hot water dissolved grease vomit and other substances that had settled into a hard crust over tiling and workbench in fridges and the large larder. It even pleased me to see the washing spin as the machine sloshed months maybe years of dirt from sheets curtains mats clothes and in the end to hang all these things up in the drying cupboard. Cleaning was my way of dealing with my brother’s anguish as well as my own. A bit like playing tetris. The pieces fell into place and other thoughts I might have attempted were kept at bay.

Bror sat on the kitchen sofa, eyeing me indifferently. He kept swigging bottled beer. When one bottle was empty he got another one from the larder. Maybe I was too late.

I heard you slept over at eskilbrännström’s he said.

You mean at john’s I countered hoping he would say more but he just shut his taciturn mouth tight and carried on staring out into the dangerous infinity.

I sat down next to him. Took the bottle from him and drank a mouthful of the tepid beer.

Do you know john I asked.

Sure everybody knows him bror replied. 17

I don’t I said.

He hasn’t been living there for all that long bror said.

Could be I said and then reconnected with reality. You have no food in the house. We must go shopping.

He leaned against me and if I hadn’t known my brother so well I might have thought he was crying.

He smelled badly of grief and sweat. I put my arm around him and stroked his hair as I had done in the past. It will be all right I said. It will be all right.

THREE

Ireversed the jeep out of the garage and tied the rubbish bags onto the trailer. Bror was taking his time.

At last he opened the door to let the cat out. It looked around then slunk down to hide under the veranda.

After the cat bror came out with the hood of his jacket pulled down over his head. He looked around then slipped into the passenger seat. Pushed frantically at all the buttons to start the heater.

His skin was pale grey. Even his freckles had faded. His hair was unkempt and greasy. He pulled strands back behind his ears over and over again.

It was slippery after the snowfall and the car lurched a bit going downhill. At the side road to eskilbrännström’s I slowed down to a crawl to look for tracks in the snow. The private road was innocently smooth.

You know nothing about john said bror. He isn’t a bad man but you know nothing whatever about him.

No I don’t and he knows nothing about me I said. Well nothing except that I murdered my father but I guess everyone knows that.

Yes said my brother everyone knows that. Though he didn’t die.

People stared at us as usual. Stopped short and scrutinised the diptych facing them until they realised they were ogling and went back to checking prices and bestbeforedates. It was hardly bigger than a village shop, a small ica grocer’s. We always called 19the family that managed it the icanders even though it wasn’t their proper name.

The icanders were mum dad and sons. They had been working here for as long as I could remember. By now the youngest son was maybe sixty but he looked the same as always except his hair had thinned. Seeing us enter the shop made him genuinely happy. He knew not to expect returners or newly moved in people. At best some impoverished refugee on a temporary placement. Which was probably why they had never bothered to refurbish or extend the shop. Foodstuffs were still stacked on tall shelves along the walls.

I manoeuvred the trolley trying to think a few days ahead followed by bror who smelled badly and seemed to be in a trance until he suddenly spotted icander senior and stopped at the shelf of tinned food.

Two tins of artichokes please bror said and got a sidelong glance in return.

The artichokes were on the top shelf. Covered in dust like tins stockpiled for an emergency.

The shopkeeper moved the steps along and climbed up. Standing below we could see the treads bending under his body. Mricander wasn’t simply fat. He was huge. His rump shook like a jelly. Sweat poured down his cheeks. Breath wheezed in and out of his massive chest.

Fuck’s sake I whispered you didn’t have to do that.

There was a mean grin on bror’s face when the man came down and handed over the tins.

Here you are he said. Hope they are as tasty as last time.

We put the goods on the counter. Mrsicander said the name of each item out loud when she entered it into the till. Coffee 20yes. Soap yes. Twelve lemonades yes. Tampons yes. Oranges yes. Otex ear drops yes.

She once worked in a pharmacy down south said bror. So what I said but he didn’t answer. He was focused on glaring at a blanklooking guy who wouldn’t take his eyes off us.

No wonder shopping puts me off bror muttered as he packed the stuff we had bought into cloth shopping bags mother had sewn by hand.

Admittedly I was sometimes amused to see people pay attention to me for just existing. Even though we came from different eggs we mostly behaved just the way people expect from twins. Read each other’s thoughts and spoke in unison.

So what’s the delicious dish you are going to cook with the artichokes I asked when we were back in the car.

His answer was to make a face.

Look seriously I said. Why torment him with your tins. He hasn’t harmed you has he.

And what do you know he replied. Nothing that’s why I ask.

Bror was staring through the window at something. Get over it he said in the end.

I swung into the service station to fill up and buy tobacco.

Are you back home again asked the till girl though I had no memory of having met her before.

You see I heard you slept over at dad’s. Lucky you didn’t get lost in the blizzard she said without looking at me.

Just one of those things I replied. And you are his daughter I asked just to be polite but she was already busy with another customer.

Finn had stopped his johndeere at the diesel pump. Returning to the village was like being back inside the truman show. Everything 21revolved in the same cycle. People moved from place to place at exactly the same time. Reality was looped like an infinity sign. As were the routines of finn and his tractor.

Cool colour I said as I passed and he startled as if I had intruded on his meditations.

Our jana he said now that wasn’t yesterday. His face had softened when he recognised me. He took a step or two towards me as if wanting to hug me but stopped in his tracks and pushed his hands into overall pockets. Malicious gossip had it he was daft but finn was just a bit of a loner. He kept himself to himself.

I bought it last year he said. You can have a go driving it if you like or just come along for a nice run. I’m going over to olofsson’s to clear out the tank he added and nodded at the gully sucker coupled to the tractor.

Not today I said. But another day would suit me fine.

So you’re staying here for a while.

We’ll see I said and walked over to the car worrying that bror wouldn’t keep upright for much longer. He was propped up against the car door and smoking. I put my arm round his back and talked him into his seat. We’ve got to get to the dump in time too I said.

You mean the recycling centre said bror as he opened the window a crack and lit another cigarette. Yes whatever.

It’s been moved bror told me. Nowadays it’s tucked away next to the sewage treatment plant. Open Mondays and Thursdays seven to twelve. When the week has an even number.

And uneven weeks.

Closed he said.

So we set out homewards instead. 22

Remember shooting dump rats with air rifles I said to lighten the atmosphere.

Yeah that was great he replied. Until you happened to shoot rogergran in the leg. Who did I said. Not me. Wasn’t that you.

You me you me who cares he said. One of us anyway.

Sure I said. The cowberrygirls gave us a lift home. Roger sat next to you. He was crying and his calf was bleeding. He cried all the way back.

Roger always has been a crybaby bror said.

Once back home we helped each other put away the things we had bought in the food store part of the cellar. It seemed I still thought of the kippofarm as home.

It was messy even down there in the cold dark space where only food and overwintering geraniums had a life. He had come down for more than just fetching onions and potatoes. On the floor stood an ashtray full of fagends and empty beer cans were scattered here and there. It was freezing.

What do you get up to down here I asked.

Try to feel things he said. Sometimes it seems nothing is for real. Then I come down here and sit on the floor and get cold. Well try to feel that I’m cold.

My brother had keeled over and needed help to right himself. I was pretty certain that he kept going on cigarettes and alcohol and didn’t touch food. He was emaciated like a pauper.

Together we gathered the rubbish into the ica bag and then clambered up the steep steps.

It suddenly occurred to me that I hadn’t given henrik a thought. There had been no room for him. I decided to stay for a little longer than planned and went off to reinstate myself in my old girlhood bedroom. Bror leaned against the doorframe watching 23as I made the bed with clean sheets and put an extra blanket on top. The pink woollen blanket was the same type as at john’s. They must have gone to the same auction.

On the walls okej magazine covers with sexy popstars mingled with childish drawings and pictures that had been hung in my room because they had to hang somewhere. Even my childish ornaments were still in place. Keyrings shells fool’s gold and stones from the seashore placed on embroidered runners that my mother enjoyed making in such quantities they had to be stored in boxes kept in the coldattic.

You can say what you like about her but she was ace at embroidery bror said.

He shifted from where he stood to settle at the foot of the bed. You didn’t come when she fell ill he said. She asked for you and I phoned you. You could have come.

I replied with what I had said when he phoned which was that I never wanted to see her again. Neither alive nor dead.

The wind had grown stronger now and made the walls creak but the room was nice and warm as if it had never stood empty and cold.

It never did bror told me. She stubbornly kept your room warm in case you’d come home again. I thought it was unnecessary but didn’t have the heart to tell her how it was.

How what was I wondered. We pushed our thin strands of hair back behind our ears.

Why did we say mother instead of mummy mum mumsie or possibly siri. I vaguely remembered it had started with a norwegian tv soap but after all these years it’s impossible to call her anything else. It followed that dad became father on the rare occasions we mentioned him at all. 24

Bror got up and asked if I wanted something to eat or drink. Then went down to his room.

I undressed. Crawled under the shiny red padded quilt and wanted to think about the night in the pullout bed at eskilbrännström’s but instead I thought about mother and that she had never turned off the radiator. Now I was back in my warm girl’s room and meanwhile our mother was lying confined in her carehome bed after a stroke. Maybe sometime I said to myself and turned on my mobile. The lists of calls and messages were both empty.

That jana might phone of course. Or send a text. But what could she say. Hi for instance. Or maybe hi good to meet up thanks for yesterday great paintings hope we meet again.

On the other hand, jana might decide to do nothing of the sort. Especially since she didn’t have his number.

At breakfast the house was still silent and the door to bror’s bedroom stayed closed even though I busied myself with putting food on the table and brewing coffee. I turned up the volume on the weather forecast monotone. It was going to be a nice day. The wind had died down. The dripping roof was a hint of spring.

I found an anorak in the cupboard under the stairs. Then a pair of mother’s handknitted gloves and better still a pair of reindeerskin boots that more or less fitted me. I considered borrowing bror’s tegsnäs crosscountry skis. They were leaning against the veranda rail. The snow was still deep and walking would be tiresome.

The key to the gun cupboard hung on its usual hook. Mostly out of curiosity I unlocked it. Obviously my brother’s fascination with weapons had not cooled. I examined the guns one by one. Weighed them in my hand and touched them. Tested the rifle sights and could not resist a newlooking .22.

I took it with me outside placed the rifle on my shoulder and 25aimed at a fieldfare. My hands were a little shaky but the stock felt just right and so did the weight of the gun.

Crow is the only thing you can hunt for now. Bror was standing on the veranda.

He kept shifting from one leg to the other. His eyes wouldn’t quite open to the early spring sunshine. There were puffs of stale booze on his breath.

Though there are hardly any crows left either. Not in the forest anyway.

It’s a good gun is it new I asked and he nodded. I thought you liked wooden stocks better.

He shrugged. Shoot us a black grouse.

Despite the thaw the skis rode the snow quite easily. I skied downhill towards a car track through the forest that was cleared in the winter for the holiday homers and where the wild birds liked pecking in the gravel scattered by the snowplough. On my back the rifle felt light. The sun warmed my face. My mind was bright and wideopen to the trees and the flying creatures mostly ravens that were moving among them.

After a couple of kilometres I reached the track so I stopped and listened to the forest.

The trees were snapping with joy that the cold was easing up at last. Sheets of snow tumbled from the branches and thumped to the ground. This was the forest of my childhood. Kippoforest stroked my back with its needlerough arms.

Father had taught us how to hunt. We would walk along with the crew until we were old enough to apply for licences. Then we could join the team.

I ought to have shot the old bastard rather than ramming a hayfork into him. It would have made for a clean death instead of him 26living on as if nothing had happened. By now I could barely remember how it had happened or at times I just couldn’t. Some memories grow inaccessible. It was like putting one picture next to another with most of them perfectly focused. That one shows him beating up mother that one shows him beating up bror. Then a totally blank picture. Not white but with a glossy sheen like brassopolished metal.

A bird rose suddenly. Bigger than a raven. An alarmed black grouse cock. Cautiously I put a cartridge into the barrel and moved slowly towards a branch at a height that I could rest the gun on.

I had the bird in my sight. Lowered the weapon so that the crosshairs was a little below his chest and squeezed the trigger. Observed the bird’s last seconds of life until it stilled and crashed into the snow.

The long skis kept getting caught in small contorta pines. The bird had landed at most fifty metres away from me but I was still unsure where exactly it was. Taking my skis off and clomping through the snow was not an option. I would sink through the soft crust. All I could do was carry on in the most likely direction and hope the sun would not set too fast in case it took time. I was sweating under the anorak. My heels were rubbing against the sagging socks in my boots. But I had to make sure the grouse was not wounded.

Was this really the right direction I wondered. Another black grouse flew up only a few metres away from me but I didn’t shoot it. It was a hen. A sad thought invaded my predator’s mind. The female bird was looking for her partner or she would never have watched from a perch so close to me.

Then I found the dead cock lying under a solitary fir among all the pines.

I picked it up. A fine specimen of almost four kilograms. I held it to me like a sleeping baby. Its body was still warm.

FOUR

Easter eve. We cooked. Stood next to each other communing in the language of the silent. Chopped veg for a burbot soup. Bror kept topping up his glass of wine. He was becoming steadily more drunk but so far with discretion.

I was plucking and drawing the black grouse. I skinned the body and put it away in the freezer all the time sickened by the smell of the gut as half-digested pine needles oozed into the sink and by myself for being a common poacher.

Are black grouse like swans I asked bror but he only shook his head.

Hand me the garlic he said. And the thyme. Seems life in the city has made you a bit of a wimp. Besides it’s a myth that swans pair off for life. They cheat on each other and get divorced. All birds do. The females pull new males to make sure of goodlooking babies. The male drops in at the next door nest box on the offchance.

We were the same height. We had the same stringy hair and we kept pulling at it and pushing strands back behind our ears. Our pale reddish skin was freckled. It’s a pity that we rarely smiled because our teeth were straight and strong. I wondered what we were like inside. If we still were as similar.

Are you staying here for a long time he said and lifted his glass as if to toast something. How do you mean long I said. I mean are you going to live here. 28

We stood together in silence. I asked myself what the right and wrong answers might be and if there were any rights or wrongs.

Well now I said defensively I don’t know. I hadn’t told him about my job or about henrik. And he had asked no questions not until now.

There’s a job going in the homecare service he said. Because maria went and died he said. Went and went, I don’t know.

What’s that supposed to mean.

Nothing he replied and hid behind the noise of vegetables sizzling in the hot saucepan.

We ate in silence. It was not an unpleasant silence because I could hear him thinking. He thought about how he had missed me and that he wanted me to live here. We had laid a table in the bestroom. Put one of mother’s embroidered tablecloths on the empire style table and lit the candles in the chandelier.

When he had finished eating bror lit a cigarette and blew a few smoke rings.

Later we started talking. We talked about everything except what was wrecking us.

In the small hours the next morning my dead laptop stood on the table alongside the wine bottles and the small fragile coffee cups and the brandy glasses.

I applied for the post as a homecarer in smalångerparish and clicked send.

They would have to be desperate to employ someone who emailed a rough job application at zeroonefortyfive hours in the night between easter eve and easter day I said brushing crumbs into my hand.

Cheers to the homecare service and cheers to jesus in his cave waiting for the resurrection bror said. 29

Cheers to us and churchofjesuschristoflatterdaysaints I replied and staggered upstairs to face the world championship team of nineteenseventyfour. I wasn’t even born in nineteenseventyfour. But I had bought the poster in a flea market and stuck it up with drawing pins. I read the names of the players as if praying.

There was one more thing I had to do tonight.

I keyed in onehundredandeighteen to inquiries and asked to be connected to johnbrännström in smalånger.

He didn’t sound at all surprised. Thank you for everything I burbled. Thank you too. How are things between you and your brother are they all right.

So I told him sensing how tired I was. My back was aching after the skiing and all the important things I had wanted to say to him vanished.

Can we meet again I asked.

Yes.

That was it. I fell asleep but in my mind he had wrapped himself around my bony body. Next I was running in the sewage tunnel soon the water was reaching my waist and I knew there was something I should’ve remembered but couldn’t.

FIVE

It was morning. And then the morning grew late. Then midday. It was afternoon before I sat up on the edge of my bed and stared redeyed at the pale yellow wallpaper. Slowly the night before caught up with me. I had applied for a job and phoned john. I was becoming ensnared in a finelymeshed childhood net and the more it seemed I would stay in the village the more my tapeworm gnawed on the gutfat.

A hangover took over from the anguish. All the footballers georgåbyericson ralfedström ronniehellström staffantapper ovekindvall and their teammates stared down on me. They saw a miserable busted creature sitting on her childhood bed with a string of dribble at the corner of her mouth. The creature fell asleep again and woke when the light was fading into evening.

I made coffee and knocked on bror’s door. Silence in there no snoring and even no sound of breathing when I pressed my ear to the door.

I tidied away the supper leftovers and then cleaned inside some of the cupboards to pass the time. A mantra of tidy clean tidy clean tidy clean tidy clean rang in my head until it cleared enough to make eskilbrännström’s seem possible.

I settled the dog and borrowed the jeep. It wasn’t far. Just downhill through the crossing and turn right into the track.

The yard looked deserted. The house was dark but he might 31be painting or sleeping. I couldn’t remember if we had set a time to meet.

He didn’t open the door. It was locked. People around here rarely locked the door. If they did for some reason the key was hung on a nail near the door or else they left it in the lock. But there was no nail and no key and the door stayed locked.

I stood outside a door listening for signs of life for the second time that day.

The farm had been built on a low ridge with the forest at its back and with the bakehouse and byre at an angle to the house. A tractor had snowcleared the yard all the way to the outbuildings.

I almost slipped as I crossed the yard to the byre. It looked well cared for. No sign of burnt haystacks and children killed by smoke. I turned the wooden bar that held the door shut and stepped straight into the byre smells of my childhood. Cow stalls and chains on welded rings. The remembered calf stalls strewn with straw as my inner eye could still see them. Bull calves just a few days old separated from their mothers and condemned to slaughter. I heard them calling out to the cow. The cow replying from a bit away. I put my hand inside so the calves could suck on my fingers. And then he came. Father in farming overalls his belly pulling at the buttons. Black heavyboots and his broad back that always seemed to say the calves must go.

Get on with it. Settle the beasts.

My eyes adjusted to the failing daylight. The milking parlour the barn sanctuary that should always be clinically clean had large spiders’ webs spreading over the walls and dirt blown in from outside formed drifts on the floor.

The white coat dangling from a nail had turned grey with age. 32

A worn sweater with frayed cuffs lay forgotten across the back of a chair. The milk cans were lined up. Hung on the wall nearby the milking machine with its sucking teat cups that were put on the udders. If the cows had to wait for too long they complained in chorus.

I felt tugging inside my own breasts. I imagined the anxiety of having to stand there, tethered and waiting for release from the backed up milk by a hungover farmer who vented his bad temper on the animals.

We had an understanding the animals and I. How often I had whispered into their silky ears that they should kick him to death. Just as they had whispered to me. There’s a hayfork with sharpened tips.

I saw john before he saw me.

He fumbled forward in the dusk. Stumbled on something and swore. I slipped out from the shadows. We were close in the narrow milking parlour and I picked up something about the scent of his body. When I sniffed all I got was his skin. Not dry shit smell of cowpats that had never been cleared out. He pulled me closer. Our anoraks rustled against each other. My hands found a way in under his jacket. Quickly searched his body. My fingertips took snaps to keep as memoryimages. His tense arms shoulder neck the uneven skin over his temples and my fingers twisted into his hair.

He lifted me up. My legs hooked around his hips. His harelipscarred mouth against mine and our tongues swirled in chaos. His eye glowed in the dark because outside the day had become night and the stars must be glowing too.

Everything was craggy and hard and rough even his tongue but from the bulk of his body tenderness flowed into mine turning me into a newborn calf with a ravenous muzzle. Did it hurt 33did he hold me too tightly could I draw breath. He wouldn’t let me go and I didn’t want to be freed. When the inescapable cold caught up with us we walked back to the house. The moon had risen. It followed us across the icy yard.