Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

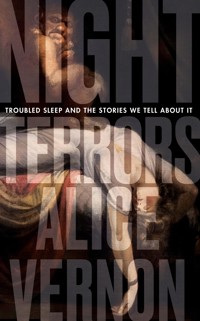

** AS READ ON BBC RADIO 4 BOOK OF THE WEEK IN DECEMBER 2022 ** 'Curious, lively, humble, utterly genuine ... a remarkable debut.' SUNDAY TIMES Alice Vernon often wakes up to find strangers in her bedroom. Ever since she was a child, her nights have been haunted by nightmares of a figure from her adolescence, sinister hallucinations and episodes of sleepwalking. These are known as 'parasomnias' - and they're surprisingly common. Now a lecturer in Creative Writing, Vernon set out to understand the history, science and culture of these strange and haunting experiences. Night Terrors, her startling and vivid debut, examines the history of our relationship with bad dreams: how we've tried to make sense of and treat them, from some decidedly odd 'cures' like magical 'mare-stones', to research on how video games might help people rewrite their dreams. Along the way she explores the Salem Witch Trials and sleep paralysis, Victorian ghost stories, and soldiers' experiences of PTSD. By directly confronting her own strange and frightening nights for the first time, Vernon encourages us to think about the way troubled sleep has impacted our imaginations. Night Terrors aims to shine a light on the darkest parts of our sleeping lives, and to reassure sufferers from bad dreams that they are not alone.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 366

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Alice Vernon is Lecturer in Creative Writing at Aberystwyth University, where she teaches students the fundamentals of storytelling. Her research focuses on representations of sleep in science and culture. This is her first book.vi

Contents

ix

‘Tonight, I shall strive hard to sleep naturally.’

Bram Stoker, Dracula (1897)

‘If we pay no attention to sleep, we thereby admit that a third of our lives are unworthy of investigation.’

Marie de Manacéïne, Sleep: Its Physiology, Pathology, Hygiene, and Psychology (1897)

x

Chapter 1

Introduction

In the early hours of New Year’s Day, 2018, I woke up to find a stranger standing by my bed. Despite the darkness, I could see them clearly. It was a woman, and she was looking down at me. She was middle-aged, had brown, curly hair, and wore a white blouse that seemed to cast a pale glow around her.

Terrified, I sat up and shuffled away until my back hit the wall, never breaking eye contact with her for a moment. She was between me and my closed bedroom door, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to get past her if I tried to run away. But as the seconds passed, my thoughts began to slow down.

This had happened before, I reminded myself. I had seen things, things that weren’t really there, on and around my bed. Spiders, usually, but occasionally something bigger. People looming down at me or peering from the corner of the room. They would flash before my eyes for a brief moment and then disappear.

This woman wasn’t disappearing, though.

I blinked hard, and she stayed where she was. Something was wrong. I started to panic; this wasn’t like the other times, 2with the spiders or shadowy figures. It was real. I could see the faint floral pattern on her shirt. For all that she looked harmless, like anyone you might pass on the street, I knew that she was dangerous. Behind her glare was a sinister feeling. She was going to hurt me. My heart was beating painfully fast; I wanted to run but I was trapped in the corner of my room, unable to escape. I reached across and fumbled for my bedside lamp.

Soft light melted away the dark. The woman was gone.

My shoulders dropped and I let my feet slide away from me, although I could still hear the muffled throb of my pulse in my ears. With shaking hands, I picked up the water bottle next to the lamp and took a sip.

I had gone back to my parents’ house for the Christmas period, and I listened out for any sound of them stirring in the room across the hallway. My door was shut and I didn’t think I cried out, but I could never be sure. I decided I wouldn’t mention it in the morning.

As I started to relax, I thought about what I had seen. I tried to rationalise it and dissect it; I always feel like a bit of an idiot when I see things in the night that aren’t really there, so it helps to be analytical rather than mortified. Staying up to see in the New Year, drinking alcohol late at night, the frantic piano-playing of Jools Holland as the clock neared midnight: it had all combined to make me hallucinate something far worse than normal. That was the explanation. Nevertheless, when I finally turned out the light half an hour later, I kept seeing the woman in my mind’s eye. I drifted back to sleep, feeling uneasy. Haunted. I hoped I wouldn’t see her again.

3Falling asleep is often easy for me. I have nights when it’s difficult to switch off, when I’ve got something important to do in the morning or I’m still churning over the events of a chaotic day, but I rarely suffer with prolonged periods of sleeplessness. I wish this was as miraculous as it sounds, but it isn’t. I don’t sleep soundly; I sleep strangely.

Ever since I was a child, my nights have been populated by monsters, aliens, and the shadow of another me who acted without my knowledge. When I was young, I used to sleepwalk around the house or refuse to go to bed at all for fear of the nightmares that tormented me. Then, as a teenager, my sleep suddenly descended into a much more peculiar realm. Since then, I regularly wake up in the middle of the night in pure terror, having experienced a ghostly assault.

Nightmares, night terrors, lucid dreams, sleep paralysis, somnambulism and hypnopompic hallucinations are some of the phenomena known as ‘parasomnias’. Even the name evokes images of ghosts and monsters, crumbling towers and overgrown graveyards. These strange states of sleep have a profound and timeless effect on our imagination, shaping art, literature and scientific investigations, and provoking paranoia of witches and, more recently, extra-terrestrial encounters. Parasomnias, even in their most bizarre and frightening forms, are more common than we might think. Recent surveys estimate that around 70% of the population will experience a parasomnia at least once in their life, with the most common forms being sleeptalking and nightmares.1,2 The problem, however, is that a combination of not remembering what we’ve done in our sleep, and fearing the stigma of admitting to hallucinations, violent behaviour or erotic dreams may mean that survey results are much lower than the 4real prevalence. When I talk to others about my sleep, I find that sometimes people will confess that they’ve experienced something similar – they just didn’t know it was ‘a thing’. In this book, we will investigate tales of sleep disorders through history, not only to see parasomnias mythologised and fictionalised, but in order to help us to talk and to listen to stories about our own troubled sleep.

I’ve always had the propensity to experience parasomnias, but it was only when I was a teenager that they took on new forms and a new significance. Since then, the occasional sleepwalk or bad dream has developed into something a lot more sinister.

When I was fifteen, a new teacher started at my secondary school. She was young – fresh out of university – and full of enthusiasm and bright ideas. But she took an immediate, unhealthy interest in me that slowly festered into something manipulative and claustrophobic. And now she haunts my sleep.

I only knew her for three years, but it took me a lot longer to shake off the anxiety and mistrust her behaviour caused. It was nothing scandalous or explicit, but it has done lasting damage. As far as I know, she was never questioned by other staff in the school. I don’t blame any of the other adults around me at the time; in the beginning, even I didn’t think things were problematic. But I suppose it was that sheltered naivety that made me a prime target in the first place. Nevertheless, I eventually began a slow and painful process of recovery. And while, mostly, I don’t think about her at all during the day, in my sleep she continues to terrify me. She is the unseen figure chasing me in dreams, the 5shadow that floats in the corner of my room, and the vivid, firm hand that grasps my neck when I’m paralysed. In this book I call her Meredith, after mara – the old term for sleep paralysis. It seems fitting.

It was my last year at that school, after which I went elsewhere to do my A-Levels. At that age, I was getting restless – I wanted to move on to bigger challenges. There were some subjects that I found particularly frustrating; English was one of them. I knew that there was so much to read and learn, but we were spending term after term picking apart the adjectives and nouns in a fake county-council planning application. Some teachers took pity, slipping me old copies of The Guardian or recommending books and films. When Meredith arrived and quickly started doing the same, I didn’t think anything of it. But I now see the difference: the culture section of a crumpled newspaper had no strings attached, but Meredith’s offerings were a tangled web of secret messages and the promise of a long, uncomfortable conversation after school.

I unfortunately had English as my last lesson twice a week, and she knew that I had a ten-minute window before the bus left without me. Once I missed the bus, I’d have to wait an hour for my parents to finish work and come to collect me. Maybe it was a coincidence, but fairly early in the term she rearranged the tables and assigned me the furthest seat from the exit. With me at the back of the queue to leave the room, she could lean across the blue door frame or stop me while she slowly rummaged in her Cath Kidston bag for a new book or film that was ‘a bit mature, but I think you can handle it’. From over her shoulder, I’d watch the corridor beyond bustle with pupils, then eerily empty out. I was alone with her, again.6

She laid bare her insecurities in that classroom, then told me how terrible the world was in an attempt to make me feel the same way. Everyone in the staff room judged her, she said. Her friends always betrayed her in the end. She often mentioned that she ‘did these things’ because I reminded her of herself. ‘It’s scary, sometimes,’ she told me. Scary for whom? I liked books, that was all, but I liked lots of other things that she didn’t: astronomy, chess, X-Men comics, angry-girl bands. I don’t think we were very similar at all, but she had a set fantasy in her mind which she projected onto me. When she found differences between us, she’d do something about it. For example, I had a long fringe that I’d do up in a quiff made rock-solid with hairspray – my friends and I had a game to see how many pencils I could hold in it. One day she came in with the same hairstyle, so I stopped doing it. Science made her nervous, she said; she pretended to throw up if I talked about a meteor shower or a newly discovered dinosaur, so I stopped talking about it. She often told me her life was overwhelming; she seemed glad when I started to feel overwhelmed myself. She wrote down a local therapist’s number and gave it to me – now we were the same.

What I remember most about Meredith is the feeling of being smothered. Physically, she would stand incredibly close to me, but I felt emotionally trapped too. She made it clear to me – her teenage pupil she had known for a month – that she was vulnerable, and any distress, any betrayal, would seriously hurt her. When I have sleep paralysis, I feel an extreme version of this claustrophobia; I’m crushed under the intense stare of Meredith, under her hands and her sharp nails, under the weight of her own emotional problems that I don’t want to exacerbate. 7I become a timid teenager again, pinned through my stomach like a little beetle to a display board, unable to escape.

Most of my strange nights involve the memory of her in some way, which makes me think that my sleep disorders are a direct result of this time in my life. But, as I’ll show in the following chapters, it’s a little more complicated than that. It’s not just for anonymity that I refer to her as Meredith; what I’m left with now is something that is quite different to who she really is. I’ve come to realise, as an adult and a teacher myself, that she was clearly in mental distress. It doesn’t excuse how she treated me, but I think I do feel some sort of pity. However, what terrorises my sleep is nothing short of monstrous. It’s a vicious cycle: every time I see Meredith, either in my dreams or as a hallucination, she becomes more frightening. The memory of that will then produce something worse, and so on. Although she represents my anxiety in a general way – if I’m worried about work, deadlines or family matters, I’ll have a nightmare about Meredith – at their root, the nightmares are still also about her. It doesn’t matter how my parasomnias twist her, a handful of incidents laid the foundations for years of troubled sleep.

The memory of the first time I saw Meredith appears in my nightmares quite often. It was the first day of term, and I was walking across a courtyard to get to a lesson. On the other side was a teacher, a young woman I hadn’t seen before. I glanced at her out of harmless curiosity, as dozens of pupils must have already done, but the look she gave me was deliberate, intense, almost rehearsed. And I remember thinking: ‘Who is that, and why is she staring at me?’

Just for a moment, I was unsettled. In hindsight, so much of the chaos that would follow was foreshadowed in those few 8seconds before I walked past her. Our initial encounter felt significant when it happened, but looking back adds an almost melodramatic weight to it. This is the image that repeats most often in my sleep: Meredith, standing still, silently looking at me. What she says in those looks can change – sometimes her eyes seem to plead with me, other times they are charged with ferocity. Sometimes she does more than stare at me, sitting on my chest and strangling me or dragging me down my mattress by my ankles.

I’m still not sure what Meredith wanted from me. I’m not sure she really knew, either. I think she was insecure in the choices she had made and saw in me a way to vicariously relive her adolescence. Or she felt lonely, isolated and misunderstood and wanted someone else to feel the way she felt about the world. But what followed that intense encounter by the drama studio was a long period of emotional and psychological manipulation that I now re-encounter in my sleep.

The history of our understanding of sleep disorders is fascinating and twisting, advancing in some areas and retreating into fear and confusion in others. Dreams are perhaps the most interrogated, interpreted and misunderstood phenomena of sleep. For over a thousand years, they have been fictionalised, dissected, glorified and demonised in an endless cycle of romanticism and rational analysis.

It’s often thought that our understanding of dreams and sleep-related phenomena moved in a uniform manner from divine inspiration or Satanic influence in the medieval era to 9a wholly neurological process in the present day, but it’s much more complicated than that. Even today, with our knowledge of sleep stages, rapid eye movement (REM) and brain waves, there are people who consider their dreams to be of cosmic origin, or their sleep paralysis episodes as visitations from angels or aliens.

Even in antiquity, when the gods of Greek and Roman religion were a fundamental part of everyday life, stories about dreams and sleep were varied. Macrobius, a fifth-century Roman philosopher, broke sleep into five categories: prophetic vision (visio), nightmare (insomnium), ghostly apparition (phantasma), enigmatic dream (somnium), and the oracular dream (oraculum).3 There is particular emphasis here on the dream as a portent.

It isn’t true to say that everyone believed that dreams were a gift from the gods, but there were numerous ideas regarding a relationship between dreams and divine influence. In ancient Greece, for example, the god of medicine, Asclepius, was believed to have a keen interest in dreams. The process known as ‘incubation’ in this era involved a sick or injured person visiting a shrine to Asclepius and sleeping there. During the night, Asclepius was supposed to either cure the person’s ailment or show them a dream which instructed them on the best cure or treatment.4 The ‘epiphany’ dream was rather commonly reported at this time, too. Epiphanies were dreams that were thought to be a visitation from a god, but this could be very widely interpreted – sometimes the gods didn’t actually appear as themselves, but their presence would be known by the message they gave. The philosopher Pliny, for example, wrote that when a man was afflicted by rabies, a god told his mother the cure in a dream. The authenticity of these dreams was said to be shown through an ‘apport’, some sort of physical object or sign such as a letter 10that symbolised the visiting god and would be left behind in the sleeper’s bed. The tale of Bellerophon is a classic example. Bellerophon, a hero of Greek mythology famous for slaying the monstrous Chimera, slept at the temple of Athena in order to receive her wisdom. In his dream, Athena presented him with a golden bridle, which remained next to him when he woke up.

The vast majority of epiphanies recorded were experienced by those in positions of power – important figures whom the gods would feasibly pick out to relay a message. The messages themselves ranged from the epic to the rather trivial: from advising strategies in an upcoming war and warning of another’s betrayal, to requesting that a statue of them be moved from one location to another. On many occasions, it is likely that members of the ruling class professed to receiving an epiphany dream to justify any drastic or strange decisions or to explain victories in battle – the gods were on their side and wanted them to win.

In Reginald Scot’s 1584 treatise, The Discoverie of Witchcraft, he describes the phenomenon of sleep paralysis in a wholly corporeal, rather than supernatural, manner. He calls it a ‘bodilie disease’ which extends ‘unto the trouble of the mind’ – not a symptom of a witch’s curse.5 Scot was somewhat correct, although his explanation uses the theory of ‘humours’ – substances which were produced by the body and caused certain symptoms and conditions if they were deemed to be ‘imbalanced’. Nevertheless, over one hundred years later, numerous people were killed as witches in Salem, Massachusetts; some of the damning testimonies that describe the victims as witches involve accounts of what sounds very much like sleep paralysis.

Sleep has always been associated with the bodily condition and the supernatural, the physical and the divine. Our 11understanding of sleep and its phenomena has been, and continues to be, tangled with these two threads. I want to know what’s happening in my brain and my body when I lucid dream or endure sleep paralysis. But at the same time, for me, sleep is like a return to the imaginative suspicion of childhood and the fear of encounters with strange ghosts and monsters. Even now, when we know so much about the sleeping brain, all the data and explanations can’t numb the absolute horror of feeling a phantom hand gripping your ankle.

I was afraid of the dark as a child, brought on by an early instance of weird sleep. I was a fairly robust kid, always curious and building things and trying to make people laugh, and I was only really afraid of spiders. Dinosaurs were my absolute favourite thing (they still are), and I used to spend hours poring over gruesome illustrations in my dinosaur books. I had a very special holographic keyring which showed a velociraptor, muzzle dripping with blood, that plunged in and out of its prey’s carcass when I tilted my hand. But then I started to have bad dreams, and they made me rather fearful and timid, dreading when night would arrive.

A few instances stand out in my memory, but the first was a series of recurring dreams featuring a tin man. I grew up fairly close to a small and very pretty Welsh town called Llangollen, which used to have a Doctor Who museum. My parents, who grew up watching the show, would sometimes take us there. The earliest memories I have of that place are ones of confusion, dark rooms and flashing lights, strange voices coming out of tall, sinister robots. I don’t think I quite understood what Doctor Who 12was, so this wasn’t the nicest experience. But what I remember most is the occasion when a man dressed up as a Cyberman was walking up and down the river path by the museum. I find this hilarious now, but at the time I was less thrilled to be placed in the Cyberman’s arms by my enthusiastic, science-fiction-loving parents.

Then came the tin man dreams. In these, I was always being pursued by a cold, tall robot and I could never get away fast enough. Sometimes I would be in our local town with Mum, outside Woolworths, and she would be swept away in a crowd of people. I’d lose my grip on her hand, and then I would find that my legs wouldn’t work; I was trying to run, but I couldn’t.

The worst thing about these dreams was the noise the tin man made. It wasn’t so much his actual appearance that scared me, but the heavy whum-whum of his metal boots coming closer and closer. He’d nearly be upon me, and then I would wake up, but for some horrible reason I could still hear the dull thud of his footsteps. I’d press my face into my pillow, clutch Doggy (a pink cuddly dog I quite literally loved to death – by the time I gave him up he was a rather macabre, one-eyed head with the back seam of his body hanging like a spinal cord) and listen as the footsteps seemed to retreat into the distance.

I now understand that this was my own heartbeat, pumping frantically in fear of the nightmare and calming down in the minutes after I woke up. I think I tried to explain this noise to my parents, but at that age I was unable to describe it in a way that made sense. To me, it was real – I was really hearing the tin man leaving my bedroom after tormenting me.

My final tin man dream took place in the playground of my primary school. The yard circled the school, and I spent many 13a breaktime running around it in games of tag and hide-and-seek. In this dream, I was doing just that, but with pure terror in place of fun. Wherever I ran, whichever favourite hiding spot I retreated to, the tin man soon followed me.

I clambered up the steps near the back door, wondering if I could somehow scale the wall and run home. But the tin man was suddenly there, in front of me now instead of behind me. This was it; he was finally going to get me.

He stopped. We looked at each other.

Slowly, his hands moved up towards his head. He lifted off his helmet. Underneath was a middle-aged man’s face, brown hair thinning back from his temples. I had never seen him before, but I knew that this was the man who had always been under the metal suit. He didn’t say anything, he didn’t even change his neutral facial expression, but somehow my fear vanished.

I woke up, and I never dreamed about the tin man again.

When we talk about a dream, we repackage it into a form that makes for a good story – we trim it down, remove any extraneous detail, embellish the moments of tension. The same applies to our episodes of sleepwalking or sleeptalking, or how witnesses report our strange behaviour back to us. This book, then, investigates how the darker parts of our sleep have gripped our imaginations across time and culture. From the dreams of antiquity to twenty-first-century experiments into the brainwaves of a sleepwalking human, we have sought to represent the elusive and subjective experiences of sleep in art, writing, and charted graphs.14

Our dreams can tell us things about ourselves, especially if we’re stressed or anxious about something. But sleep takes on a new significance in fiction; it becomes its own setting, a plot device with a plethora of uses. To show us how an upsetting event has affected the heroine in a film, we’ll see her bolt up, gasping, in bed (I only occasionally do this, and I doubt it makes me look as attractively troubled as in the movies). If a character is guilty of something, they might sleepwalk or unknowingly natter incriminating information. On the other hand, troubled sleep might be presented as supernatural; ghosts and goblins haunt bedrooms, and vampires paralyse their victims during their nightly attack. But, as we’ll see, these works of pure imagination aren’t always easily distinguishable from real anecdotes; both share a sense of blurring between what is real and what is perceived. Throughout this book, we will examine the various ways parasomnias have been depicted: in fiction from prose to video games, in court papers, private diaries, sensational news articles, experiments, and in personal accounts shared with friends, doctors, and psychiatrists. We’ll discover how sleep and dreams have been described, misrepresented, even hidden away as shameful secrets, and we’ll think about how we might be encouraged to tell our own stories of troubled sleep.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) demonstrates a spectrum of representations of disordered sleep in fiction, so it’s a good place to start our investigation. It has stuck with me since I read it as a teenager, but it was only while I was researching insomnia and sleep in fiction for my PhD that I realised why I liked it so much. 15Dracula isn’t just an infamous vampire: he is every parasomnia combined in the figure of a folkloric monster.

The book begins with the journal of Jonathan Harker, a solicitor on a business trip to Romania. His client is Count Dracula, and he stays as a guest at the mysterious man’s castle while he helps to arrange the purchase of a house in London. Soon, however, he learns that Dracula is a blood-sucking monster and, while the Count prepares himself for a journey of his own, manages to escape despite his weak and terrified condition.

Among its many readings, Dracula can be interpreted as a novel about the anxiety of intrusions. This is quite literal when Dracula crashes onto the shore of Whitby in the ill-fated Demeter, immediately making his uncanny appearance known in the form of a strange, large dog leaping from the wreckage. Soon, though, he begins to invade the sleep of guests holidaying at a nearby home – particularly two young women, Mina Murray (Jonathan’s fiancée) and Lucy Westenra.

As the book progresses, Mina becomes increasingly obsessed with sleep. She writes about the arrival and quality of sleep in many of her journal entries. It is sparked from observing her friend, Lucy, sleepwalking along Whitby’s cliffs. From this point in the text, Mina is consumed by her preoccupation with documenting her own sleep and the sleep of others. She is agitated and restless, worried about Lucy and the still-absent Jonathan. Sometimes Mina’s sleep comes easily and is dreamless, but more often it eludes her. Lucy, meanwhile, suddenly sickens with a mysterious illness. Their friend, Dr John Seward, enlists the help of his teacher, Abraham Van Helsing, to try to uncover the cause of her rapidly declining health. After Lucy’s death from unexplained blood loss, Van Helsing proves that a vampire 16moves among them, and has added Lucy to his ranks. She is swiftly dispatched, and the rest of the group, now including Jonathan, set their sights on Dracula. This is where the book seems to become particularly preoccupied with sleep. For Mina, Lucy’s night-time walk is understood to be the pivotal moment when her friend crossed a threshold into Dracula’s realm. As with sleepers through the ages, Mina experiences the vulnerability of unconsciousness – that her sleep might also be intruded upon by the monsters of folklore.

When Mina then begins to be visited by Dracula, she exhibits signs of nearly every parasomniac condition. The first example appears to be a kind of sleep paralysis, in which Mina is overcome by a ‘leaden lethargy’ that ‘seemed to chain [her] limbs’.6 Following the episode, she writes that she will ‘strive hard to sleep naturally’, illustrating her need for healthy sleep and identifying the episode as akin to Lucy’s somnambulism. After she is attacked by the Count, her sleep is documented by others. In Jonathan Harker’s journal a few nights later, he describes being woken up by Mina ‘who was sitting up with a startled look on her face’, and she exclaims that there is someone in the corridor. Upon being told that there is no one there but Quincey Morris on guard duty, Mina sighs and easily slips back into sleep. This half-awake, hallucinatory conviction of a dreadful presence bears all the traits of night terrors. The following morning, Mina demands to be hypnotised by Dr Van Helsing. The description of this scene seems to parallel hypnotism with troubled sleep; during the session, she mimics the childlike obedience observed during Lucy’s episode of sleepwalking, and when she awakens from her trance-like state she asks, ‘Have I been talking in my sleep?’ As we’ll see in Chapter 2, a form of 17hypnotism in the Victorian era was often aligned with sleepwalking, and Stoker seems to be demonstrating this idea here.

Mina’s symptoms of parasomnia seem to worsen in stages. Through sleep paralysis, she loses control of her limbs; through night terrors she appears to hallucinate frightening images; and finally, under hypnosis, she loses all autonomy and falls into the same state of somnambulism as Lucy.

Sleep is a transitional space between wakefulness and an unconscious abyss, between life and death. Parasomnias, particularly when episodes are not remembered, can be a liminal state in which the body moves and exhibits personality and emotion, but the waking, rational self is effectively ‘dead’. Vampirism in Dracula, then, is a physical existence between life and death and between wakefulness and sleep. Dracula has now become a stereotypical figure of the undead, but for Mina he is a symbol of trauma and of guilt. In the book he is a kind of synecdoche for troubled and unnatural sleep. Moreover, she considers sleep as an external force that comes to her – in much the same way as she is visited by the Count – rather than recognising it as a bodily function originating within herself.

The very idea for Dracula is said to have come to Stoker in a nightmare. When I read it now, it is less about Dracula’s blood lust and desire to colonise the world with the undead, and more about a kind of contagious parasomnia. Nightmares lead to lucid dreams, from which hypnopompic hallucinations, sleep paralysis and somnambulism might develop.

Ghost stories, particularly during the nineteenth-century boom in the genre, feature plenty of incidents that blur the line between sleep and the otherworldly. They often focus on the bedroom as the scene of a haunting, and it’s usually an 18unfamiliar setting for the protagonist – a hotel, or as a guest in a creepy mansion. Again and again, these stories feature spooky manifestations witnessed by protagonists on the edge of sleep. In Edward Bulwer Lytton’s ‘The Haunted and the Haunters’ (1859), the narrator wakes to ‘two eyes looking down at me from [a] height’ and finds himself ‘weighed down by an irresistible force’.7 This is what we now know as sleep paralysis, a sense of immense pressure often accompanied by a frightening hallucination of a malevolent figure.

The terrifying climax from M.R. James’s ghost story ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’ (1904) presents a bed as the site of abject horror. The protagonist, Parkins, is on a holiday, and while walking along a beach he finds a whistle half-buried in the sand dune. Naturally, he blows it. Later, back in his twin room at the hotel, something odd begins to happen to the spare bed: it looks as though it has been slept in. The following night, the true haunting occurs. Parkins wakes in the night to find the sheet in the other bed moving, then rising, and assuming the outline of a figure. In the moonlight, Parkins sees that the sheet has ‘a horrible, an intensely horrible, face of crumpled linen’.8 A literal ghost in a bedsheet. As with many of these stories, the protagonist is introduced to us as a staunch sceptic of all things supernatural, but his experiences convince him of an afterlife. This is the hold strange sleep has over us: it can make us believe in ghosts, even though the only ghosts we see are the ones we create.

Beds are places of rest, safety, security, but only if your sleep is peaceful. For insomniacs, the bed is a cruel tormentor; for those of us with parasomnias, the bed is a haunted crypt.

19When I was a PhD student, I experienced sleep paralysis for the first time. It brought the memory of Meredith back in a way that gave me terrible anxiety for a few months. In fact, for a while, it felt as though I had gone right back to being fifteen again. I couldn’t think about anything else but Meredith, such was the horrifying clarity with which she had reappeared in my sleep. About halfway through my thesis, I realised that my interest in sleep wasn’t so much about insomnia, which I’ve never really had, but in the weird dreams and hallucinations that I’ve experienced all my life. I think I had always wanted to write about sleep, but when I was drawing up my PhD proposal, I wasn’t quite ready to look so closely at my own situation. Towards the end, it was all I wanted to do. And so I started to think about this book.

While we’ll be looking at modern diagnoses and treatments, this book won’t offer suggestions of cures for these sleep disorders. Instead, it is primarily interested in examining the effect of parasomnias on society and how these phenomena have been interpreted and misinterpreted in the past. From witches to aliens to sleepwalking murderers, we will explore how representations of sleep disorders have developed, and how we learned to separate sleep from the supernatural. By examining these stories, and looking inwards to our own experiences, perhaps we’ll get to know our sleep better.

The book’s journey begins with the first parasomnia I ever experienced: sleepwalking. Also known as somnambulism, it is a common parasomnia, and can range from the sleeper making small movements to committing elaborate crimes. This opening chapter will look at some of the curious examples of sleepwalking in history and culture, from young women whose nightly 20walks became a source of entertainment, to people who committed murder in their sleep.

I then move to a darker part of my sleep. One of the first ways Meredith irreversibly changed my sleep was in the form of hallucinations, when I started seeing spiders in my bed. When I opened my eyes, one would be scuttling next to my pillow, or aiming for my forehead as it descended from the ceiling. After a brief moment of panic, I would realise that I had been hallucinating. These dream-like images onto the waking mind are known as hypnopompic hallucinations, and they’re vivid enough to be easily mistaken for something real. Chapter 3 will discuss examples of hypnopompic hallucinations, focusing particularly on their influence on Victorian ghost stories.

I often see things that aren’t really there, but sometimes I feel them, too. I wake up with my body heavy and rigid, and a sense that something, someone, has their hands around my neck or is dragging me down my mattress by my ankles. Sleep paralysis was once interpreted as being ‘ridden’ by the incubus or succubus, a shadowy, impish figure that sought to squeeze the life out of its helpless victim. It led to suspicions of witchcraft, demonic possession, and ghostly visitations. In the next chapter, we will look at the history of our interpretations of sleep paralysis, and the ways in which its control over our bodies and minds has emerged in fiction and art.

Night terrors, on the other hand, often lack the lucidity and sense of being awake that are characteristic of hypnopompic hallucinations and sleep paralysis. Known as pavor nocturnus, this parasomnia is frequently seen in children, but can also affect adults. The sleeper is suddenly seized by a fear so strong that they often scream or hurt themselves and others in a frantic 21attempt to flee the object of their distress. Chapter 5 explores the scientific and cultural depictions of the condition, and brings it to life through the experiences of sufferers like my cousin.

Chapter 6 will explore our unrelenting fascination with dreams and nightmares. Sigmund Freud emphasised our need to understand this nightly phenomenon in The Interpretation of Dreams (1901), but many earlier, and now largely forgotten, texts provided the foundations for his theories. This chapter will celebrate some of the pre-Freudian pioneers of dream research, looking at how their ideas predicted some of our most recent sleep discoveries. As well as providing endless scientific and psychological mysteries, dreams can also be a valuable source of creativity. Robert Louis Stevenson, for example, relied on his dream adventures to provide inspiration for his stories.

I have always been a vivid dreamer. Dreams are colourful, tactile, immersive dramas that cling to me like a dazzling cape for the duration of my day. If the dream was happy or exciting, I can feel it warming my general mood. If the dream was distressing, it becomes an almost physical weight on my shoulders, and if I was hurt in any way I can often sense a dull prickling at the location of the dream-injury. My childhood nightmares terrified me beyond any other experience in my life, to the point where I couldn’t sleep in my own bedroom. For me, dreams aren’t just the debris of a good night’s sleep. They deeply affect me. I write them down, analyse them like a painting or a poem, chew them over at the back of my mind. If my dreams suddenly became shallow and dull, I would feel as though I had lost an important piece of myself. Good or bad, they are still an essential part of my life.

But when I was entangled with Meredith as a teenager, my dreams opened up like an old gate in an overgrown garden. 22Over and over again, I dreamt of the corridor leading up to her blue door, and of being in her classroom. Then, one night, I realised the truth of the situation: I wasn’t cringing under Meredith’s intense stare, but asleep in my bed. I became awake within a dream. This phenomenon, known as lucid dreaming, has been written about for centuries but because it is a rare and fantastical experience, until recently it was kept on the fringes of sleep research. It has been discussed with scepticism; prior to modern experiments proving its occurrence, the only evidence for lucid dreaming was the personal testimony of those who had experienced it. The work of Stephen LaBerge in the 1980s, its representation in films such as Satoshi Kon’s Paprika (2006) and Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010), and recent successes in inducing the state, have contributed to its prevalence in modern psychology. Chapter 7 will explore the wonderful and bizarre phenomenon of lucid dreaming, revealing historical examples and modern research, as well as discussing how it can be used for therapeutic and creative purposes.

Night-time, for me, is a source of both fear and familiarity. I used to dread its arrival when I was a young child; the way the house seemed to hold its breath and bedrooms became menacing, shadowy spaces. It felt oppressive, as though I was being watched by monsters I couldn’t see myself. As I got older, my relationship with the night changed, and I discovered that it could be soothing as often as it was scary. It stopped being a writhing, shapeless terror and became something warm and familiar like a big, brave dog curling itself around me.23

It’s for this reason that, at least at this point in my life, I yearn for the dark evenings of autumn and winter. I like some aspects of summer; the flowers, the interesting bugs, the way a cold beer becomes extra satisfying. But the hot, inescapable sunshine and the starless, navy-blue nights of west-coast Wales make me feel as though I’m in a place where I don’t really belong, like a tropical fish in an aquarium.

Just before the coronavirus lockdown in early 2020, I went to the Science Museum in London for the first time. I think my inner child resurfaced that day, and I remembered how cool science – especially space – could be. And in the long, troubled summer that followed, the memory of this trip was one of the things that sustained me when I felt particularly low. In the autumn, as the nights started to get longer and darker, I bought myself a pair of astronomy binoculars. This might sound a bit sad, but the first time I took them outside and looked up, I nearly started crying.

Throughout the winter, I went out to look at the stars whenever the sky was clear enough. I would wrap up warmly, fumbling in my thick gloves, and step outside onto the dark little terrace with my comically giant binoculars. With the lenses pressed up into my eyes, it felt like I was somewhere else. I was in this safe, enclosed, quiet little world with Jupiter and Saturn and the Pleiades. I could hear the waves sloshing against the promenade in the distance, the sound of seagulls and other animals nestling down, and those cosy clangs of pots and pans as people made dinner in the houses behind me.

This is how I like my nights to play out. After a little while stargazing, I go back up to my flat. I switch on the small, warm lights and lamps I have dotted around, and I make a cup of 24camomile tea. I started drinking this when I was younger, on holiday and so desperately bored in my hotel room that I sampled all the teas in the caddy just for something to do. Camomile tea smells like the sweepings from a hamster’s cage, but somehow I acquired a taste for it and now I drink it almost every evening. I’m also a big fan of classic Hollywood movies – the more melodramatic and fabulously costumed the better – so I might watch something before heading to bed. Then I usually read a few pages from a non-fiction book. Lastly, I do a bit of meditation. Nothing fancy, and only for a few minutes; it’s just a way of calming down my breath and my muscles if I’ve gone to bed feeling tense about something. It helps me let go of the day.

And then, I melt into bed, into the darkness.

I have a habit from my childhood of imagining some sort of story as I drift off; they used to be stories in which I was a glamorous hero with every single superpower combined, but in adulthood it’s become more of a boring visualisation exercise. I fantasise about planting seeds in a garden, or wandering alone around the Natural History Museum, or revisiting scenes in a film I recently watched to try to figure out what on earth was going on. After a few minutes of this, my thoughts become syrupy-slow. I try to focus on the image of my hands tying string around a tomato seedling, but then I forget what I was doing, what I was thinking about just a second ago.

It may or may not be related to my parasomnia bingo card, but sometimes I experience an odd sensation just before I fall asleep. It is so subjective, possibly more so than my other sleep phenomena, that it’s quite difficult to describe. I have a sense of where ‘I’ am in my body – I’m the twittering little voice behind my eyes, floating in some abstract space in my skull. But I know 25where that is, like being able to navigate the living room in thick darkness – you know where you are in relation to the rest of the room and furniture. When this sensation happens, I have the most peculiar distortion of my position in the world. It feels as though ‘I’ have shrunk inside my body; I’m no longer in a living room but in a vast football stadium that keeps growing and growing. My eyelids feel as though they’re miles away. Sometimes it affects different parts of my body or the space I can sense around me – my head might suddenly feel massive, or the bed shrinks to the size of a box of matches. It stops as soon as I open my eyes.