Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

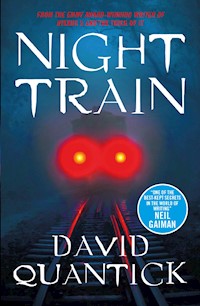

"David Quantick is one of the best kept secrets in the world of writing. He's smart, funny and unique. You should let yourself in on the secret." – Neil Gaiman From Emmy-award winning author David Quantick, Night Train is a science-fiction horror story like no other. A woman wakes up, frightened and alone - with no idea where she is. She's in a room but it's shaking and jumping like it's alive. Stumbling through a door, she realizes she is in a train carriage. A carriage full of the dead. This is the Night Train. A bizarre ride on a terrifying locomotive, heading somewhere into the endless night. How did the woman get here? Who is she? And who are the dead? As she struggles to reach the front of the train, through strange and horrifying creatures with stranger stories, each step takes her closer to finding out the train's hideous secret. Next stop: unknown.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 329

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for Night Train

Praise for the Author

Also by David Quantick

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Acknowledgments

PRAISE FOR NIGHT TRAIN

“I hadn’t planned to read all of Night Train in one sitting, but I found myself doing just that. David Quantick’s novel sets up a vast mystery and barrels deliriously toward a conclusion you’ll never see coming like, I don’t know, some kind of railed vehicle that operates in the dark.”

DAVID WONG

“If you’re looking for an escapist, absorbing, full-throttle read, then you need to hop aboard Night Train immediately. Snowpiercer on acid, it’s weird, intriguing, wickedly funny, and wholly entertaining. I loved it and didn’t want the journey to end.”

SARAH LOTZ

“A dark, nightmarish journey into a brand new sort of Twilight Zone, David Quantick’s Night Train is breathless, frantic, and creepy as hell. You’ll never see the twists coming.”

CHRISTOPHER GOLDEN

“Starting a trip on the Night Train is like waking up in a scary game with no rules. I enjoyed trying to work out the parameters of this strange new world with Garland and exploring its ever-more-surreal carriages. When we finally start to discover where we are, we realise there’s no going back. Night Train is pacy, amusing, and gory, and an entertaining companion on a dark journey.”

LOUIS GREENBERG

PRAISE FOR THE AUTHOR

“David Quantick has a medical condition whereby he literally cannot be unfunny.”

CAITLIN MORAN

“David Quantick is one of the best-kept secrets in the world of writing.”

NEIL GAIMAN

“If you choose to only live in one alternative reality make sure it’s the one in which you read Sparks by David Quantick.”

BEN AARONOVITCH

“Unfolds like The Da Vinci Code, only with a sense of humour and better grammar.”

THE INDEPENDENT

“Ingenious, likeable, funny and entertaining.”

THE SPECTATOR

Also by David Quantick

and available from Titan Books

All My Colors

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Night Train

Print edition ISBN: 9781785658594

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785658600

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: August 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2020 David Quantick

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Simon

“All aboard the night train!”

ONE

Night. Blackness, anyway. Darkness. No light. Nothing. Just night.

Then a thundering crash. A deafening noise, too much to bear. A huge, smashing shock to the ears.

Everything shaking. Walls, roof, floor.

Still no light.

She managed to move, somehow, and tried to stand. At once she was slammed back into the ground. She tried again, but it was as if the floor had its own gravity. This time at least she was thrown across the room. She hit the wall, which means she found the wall. Now she could figure out the borders of her confinement.

Feeling her way along the wall, as she stumbled to her feet and was thrown down again, she marked the perimeter of the room she found herself in. It was big, at least twice as wide as her length, taller than her – the shaking of the room so violent that she didn’t even think about reaching for the ceiling, let alone trying to touch it – and, as she was beginning to find out, much, much longer.

She made her way along the wall in pitch blackness. Her eyes adjusted to the dark, but as there was nothing but dark, she still could not see anything. For a moment she touched her eyes to make sure she still had eyes: it was a horrible, lurching moment, but right then anything was possible.

She found a fingerhold in the wall. The darkness was total, and the noise around her still a random crunching, roaring thunder, as if an ocean were pouring into every room of a house, so she used her remaining senses instead.

The wall she was touching was not cold. She felt along it with a finger. A snag, like a splinter. It might have been wood.

She inhaled. The air was metallic, oily, but there were other smells, more animal.

She decided to take stock of her situation. There were too many thoughts to process, so she started with the basics.

Where is this?

What is it?

How did I get here?

How do I get out?

Another question came into her mind. Even though it was her question, it both surprised and frightened her.

Who am I?

Remembering things is easy, she thought, you either remember them or you don’t. Nevertheless, she tried to remember, strained as though her memory was a physical thing like a muscle that she could make work. Nothing came. She could only remember the last few minutes. If she tried to rewind her memory back any further than that, she hit a wall.

Nothing doing, she thought, and decided to concentrate on some other basic questions. Where is this? seemed like a good place to start. She began to concentrate on her surroundings, which was far from easy, as her surroundings did not make it easy to concentrate, might even actually have been designed to make concentration impossible. All this needs is a death metal band playing in the background and it would be perfect, she thought, and then wondered how it was she knew what a death metal band was yet could not remember her own name.

Maybe whoever I am just really likes death metal, she thought and, to her surprise, actually laughed. The laugh was immediately swallowed up in the hammering noise of the pitch-black room, which was now shaking like a skyscraper at the peak of an earthquake. She lost her grip and slid across the floor, slamming into the wall on the other side.

She decided to give up on standing up, and instead began to crawl across the floor, sticking close to what felt like planks beneath her body. This was a slow but effective means of movement, and she was able to crawl forwards further than she was thrown backwards.

The noise, and the blackness, continued. Whatever was causing them did not care, or probably even know, that she was there.

She made her way towards she didn’t know what, almost flush with the floor now, using the weight of her limbs and the roughness of her hands to try and grip the floor. Once she was thrown backwards half the length of the room, and once she even slammed sideways into the wall again, but she was making some kind of progress.

And then, after what seemed like hours, her finger touched the wall at the front of the room. She slipped her fingernails into the cracks between the planks, the nearest she had to a handhold, and raised herself onto her knees. She waited for a moment in case the room threw her back across its floor, and then slowly got to her feet. She began to move sideways crab-fashion across the width of the wall.

If this is a room, she told herself, it’s got a door. Every room has a door.

She didn’t actually know if she believed this, but it was a good premise to act on. After a minute or two, she found something on the wall. A raised piece of wood. She felt up and down and confirmed that the wood was vertical. Hardly daring to hope, she reached out to grip the almost-flush post. She had just managed to get a weak grip on what she presumed was a door frame when, with a gigantic crashing sound like a truck being dropped from the top of a building, the room shook and convulsed and she was thrown several metres back again.

I’m getting angry now, she thought, and was pleased to discover that whoever she may be, she clearly wasn’t the kind of person who gave up easily. Slowly she crept her way back to the front of the room. With great care she got to her feet, and once more felt for the door frame. This time she managed to stand and was even able to reach up on tiptoe and find the top of the frame. Her hands moved hopefully across the wood in the middle of the frame and then – yes! she thought – there was, incredibly, what felt like a handle in the middle of the door.

She held onto the handle for a minute or two, more for reassurance than anything else. And then, when she felt that the room wasn’t going to once more throw her back, she closed her eyes (why? I can’t see anything) and turned the handle.

At once she was blinded. A yellow light filled her eyes and rendered them useless. When the blindness faded, she saw that she was in a doorway. She stepped forward, and her foot met cold air. The room was not connected to anything, but led out to –

Another door. A door shaking like this one in its frame and suspended over something moving.

She looked down. In the glow of the yellow light, which she now saw was a lamp hanging from the wall in front of her, all she could see below her were metal rails. The rails seemed to be moving at an incredible speed, but of course she knew it wasn’t the rails that were moving but her.

A train, she thought. I’m on a train.

She stood there for a few moments, her body crucified in the door frame, swaying in the gap between what she now saw were two carriages. Behind her, blackness. Ahead of her, she had no idea. She was about to reach out for what she hoped was another door into the next carriage when the train lurched, bucked and nearly threw her down (onto the rails, she thought).

She steadied herself, then something slid abruptly towards her and jarred her heel. Still holding the frame with one hand, she lowered herself, reached down to pick up the object and lifted it up. In the yellow lamplight it was clear what the object was: a set of manacles, its chain broken in half. Unconsciously she felt her wrist, and for the first time noticed that the skin was broken.

Suddenly horrified, she dropped the manacles. They fell onto the tracks and were gone in seconds. She was filled with a powerful desire to get away from there and nearly stumbled as she stepped over the gap between the two carriages.

There was a metal handle on the second door and she was forced to hold onto it to avoid falling. She pulled it back, and the door swung open, almost pushing her over. She slammed it shut, thought for a moment and then, holding her breath, opened the door again. As it swung out, she reached round with her free hand and found a handle on the other side. In one sudden move she slid herself around the door and, as it slammed shut again, rolled onto the floor.

She lay there for a moment, her heart thundering as though it too were part of the train. This carriage was warmer than the first, and quieter too. Compared to what must have been her prison, it was like a womb. Reluctantly, she opened her eyes and got to her feet.

She was in an ordinary train carriage. There were windows, but they only reflected the lights of the carriage. A thin strip of carpet ran the length of the carriage, and on each side of it seats, with tables. Every seat was occupied. Men and women, on their own, or in pairs, and sometimes even three or four. And every single one of them was dead.

She walked up and down the carriage, not touching anyone, looking carefully for signs of life. There weren’t any. None of the fifteen dead people – she did a head count – was moving, breathing or showing any indication that they were anything but dead. Without disturbing the corpses, she could not see if they died violent deaths or even (it occurred to her) if they were dead when they were put in the carriage. There were no wounds, no cuts, no signs of disease or even distress. Just fifteen dead people, slumped in their seats like commuters asleep on an early morning train to work.

The fifteen dead were an unremarkable lot. They wore unremarkable clothes in an unremarkable variety of styles. A young man in a cheap work suit, his tie loosened at the neck. A middle-aged woman in a thick woollen coat, scarf laid neatly in her lap. An old couple, his head on her shoulder, her face turned to the window. A big fat man with a shaven head in a sleeveless T-shirt, prostrate over a table, his huge hands like fleshy books spread flat on either side of his facedown pink skull as though he were praying to some pagan idol. A soldier in combat uniform, kitbag occupying the seat next to his. Two teenage girls in floral tops, mouths open, eyes shut, their mobile phones still close to them.

She moved the soldier’s kitbag to the floor and sat down next to his body. She remained there for a while, not quite listening, not quite seeing, just letting the situation flow into her. The train continued to bluster its way through the dark. This made her think. She leant over the soldier’s body and, making a tunnel with her cupped hand, peered out of the window.

It was hard to see anything with the reflection in the glass from the brightly lit carriage, but after a while she was able to distinguish the inside from the outside. Not that there was much to see. Most of the external world was in darkness. She thought she could see smoke, far off, and perhaps light, but with no idea of where she was – high up, in the country, or even a tunnel – it was impossible to gauge. And then she saw, with a start, something explode into brightness. She stared through the glass as a faraway object – or a small one close by – erupted into flame and sparks and smoke, like a volcano going off, or (this thought is less agreeable) a bomb. The explosion, if that was what it had been, was entirely silent.

From further away to her right there was a second explosion, and then a third. Suddenly the whole landscape was lit up by explosions. It must be a bombing attack, she thought. But now she considered it, the explosions did not look like bombs going off. They seemed to be coming up from the ground, not down from the sky. Like furnaces all triggered to go off at once.

Then, as quickly as they had burst into existence, the explosions stopped, and she was left in a silent carriage with fifteen dead people.

She felt the soldier’s kitbag at her feet. Suddenly inspired, she hoisted it up and spilt its contents over the table. A half-drunk bottle of water, a pair of underpants, a T-shirt and a balled-up pair of socks. Trousers, a jersey, two pairs of training shoes. A washbag, containing a toothbrush, a razor (she nearly sliced her fingertip before she saw it) and a tube of facewash.

And crumpled up in balls inside the training shoes, a newspaper. She pushed it all off the table except for the newspaper, unfolded it and flattened it down on the table. She tried to read it, but none of the words made any sense. Not because they were written in a different alphabet, or even a different language, but because she could not make the component parts of the words link up. The letters just floated there, refusing to join up. It was like being a victim of a mental disorder that refused to let the brain assemble eyes and ears and a mouth to form a recognisable face.

After a few seconds looking at the letters on the printed page actually began to hurt, and she had to close her eyes.

She opened them again and looked at the dead soldier beside her.

“This isn’t normal,” she told him, and her voice almost squawked from lack of use. “Someone’s done this to me.”

She picked up the newspaper again and – not looking at the letters – started to tear through the words and around the images, the photographs and maps and even cartoons in the paper.

I’m not done yet, she thought, as she discarded the printed words and smoothed out her cache of torn-out images. She had no idea what to do with these pictures and photographs, but there is, she believed, no such thing as useless information. She folded the small squares of paper and was about to put them in her pocket when she stopped, and for the first time looked at what she was actually wearing.

It was a green jumpsuit, the same colour as the dead soldier’s uniform, except that where the soldier’s clothing was rough and cheaply made, the jumpsuit was woven from a more expensive cloth and was well tailored. Clearly whoever made these clothes was working to a sliding scale of equality.

The jumpsuit had breast pockets and blank epaulettes, and a blouse underneath of a similar, but softer fabric. There were long zip pockets – empty, she checked quickly – and on her feet she was wearing functional but comfortable boots (monkey boots, she knew they were called).

Above one of the pockets was a thin green script with lettering on it. Looking down on it gave her a headache, so she had to stop, but naturally she could not help wondering what it said. It might be my name, she thought. Someone’s name, anyway.

She put the tiny pile of photos in one of her pockets and, after a moment’s thought, decided she was thirsty.

“Excuse me,” she said to the dead soldier and unscrewed the top of his water bottle. She sniffed it, decided that whatever killed him probably wasn’t in the water, and took a swig. It tasted fine, if a little bit stale.

“Thanks,” she said and just managed to stop herself offering him a swig. She put the lid back on, stood up and looked around the carriage at her fifteen dead companions.

“Sorry to do this,” she said, and began to loot their corpses.

* * *

The fifteen dead gave up few surprises. None of them had any wallets or purses, and there were no identifying labels in their coats or shirts (she considered looking in their underwear but decided against it). There were no photographs in their belongings: in fact, very few of them had any belongings. She found no small items, either: no keys, no coins, no sweet wrappers, nothing that could be called a clue. For train travellers, they were surprisingly lacking in train tickets.

The only personal possessions she found, oddly, were phones, and even then the only people who had them were the two teenage girls, their mobiles placed carefully in their laps like precious dolls. The phones themselves, despite being fully charged, were no use to her. There was nothing in or on them, no call records or applications. They were not receiving a signal of any kind and even the photo folders contained nothing but generic background swashes. As an experiment, she pressed “call” on each phone and tried a couple of random numbers, and got nothing but silence. Still, she pocketed the phones (and a charger she found in the soldier’s kitbag, which she checked and found compatible) because, while they might have been nothing, they were all she had.

Not really knowing why, she rearranged the fifteen dead as she found them, finally putting the kitbag next to the body of the young soldier. She was about to decide on her next move when she heard a click.

She turned, a second late, to see the compartment door ahead of her open and something hurtle at her, a massive forward-moving blur. Before she could see what it might be, it was on her. A blow to the head and she was on the ground. Something was keeping her down. Sprawled on her back, eyes closed from the pain, she held her arms in front of her face to prevent more blows.

None came. She opened her eyes, and saw that her attacker was – she could not say. It looked, and felt, like a giant torso was on top of her. Then she became aware that the torso had a head, quite a few metres up from where she was lying. Two arms and two legs framed the torso, each arm with a clenched fist at the end.

The head was shouting at her now from its massive mouth, and at first the shouting was so loud she could not make out what the head was saying.

“I can’t hear you!” she shouted back, which struck her as an absurd thing to say to a head shouting at you from a few metres away.

“Who are you?” shouted the head.

She was about to reply when a fit of laughter struck her. The head stopped shouting and the fists dropped as she laughed uncontrollably. Finally she managed to stop and, wiping her eyes, said to the enormous figure sitting on top of her:

“I don’t know! I don’t know!”

And this set her off again.

* * *

The torso got to its feet and, without asking, pulled her up. Now she saw that the man who’d attacked her was not quite as big as she’d thought, just very tall and very thin.

He pushed her, not roughly, into a seat and looked down at her. His face was creased by a bony ridge where his eyebrows should be, and his nose was squat between two large brown eyes. His head was bald and his big pink ears looked like someone had stuck two gigantic slices of bacon to the sides of his head.

This thought set her off giggling again. The giant leaned in and studied her.

“Who are you?” he said.

“Please don’t start that again,” she replied, and managed to control herself. She looked him in the eye. If she didn’t think of the bacon ears, she was all right.

She said to the giant, “I don’t know who I am. Who are you?”

The giant frowned at this. He pointed at his chest, and she saw that he was wearing the same green uniform as her, just more generously made. He pointed at the strip of writing over his pocket.

She shook her head.

“I can’t read that,” she said.

“BANKS,” said the giant, making the words big in his mouth. “I am BANKS.”

Banks pointed to the strip on her jacket.

“And you are garland.”

She looked down at the writing. Now, bizarrely, she could read the letters without pain. Looking at them now even upside-down, she saw that the giant was right. Her name, if the words were to be believed, was Garland.

She shrugged.

“I’m Garland, then,” she said. “Hello.”

“Banks,” said the giant, and extended his enormous hand.

She looked at it for a second, then took it.

“Pleased to meet you, Banks,” she said.

Then Banks winced and suddenly grabbed his arm.

She looked at his sleeve; it was bloody. Without asking, she grabbed the fabric and began to roll the sleeve up. Banks said nothing as she peeled the stiff fabric back. Underneath the cloth, the massive arm was reddish brown with dried blood.

“Wait here,” she said. She had seen a door with an image of two stick figures on it. She went to it, and it was unlocked. Inside there was a toilet, a washbasin and some thick tissues. She turned on the tap and hot water flowed out: soaking as many tissues as she could find, she took them back to Banks.

“This may hurt,” Garland told Banks.

“Everything hurts,” said Banks as she began to wipe the blood from his arm. He looked to one side throughout the cleaning process.

Garland got through six or seven tissues before the arm – hairless, like a wax dummy’s – was free of blood. There was a deep cut, healing but still raw.

“How did this happen?” she asked Banks.

Banks looked at her and smiled.

“I don’t know,” he said.

He looked round, and took in the fifteen dead.

“This is a bad room,” he said. “I know a good room.”

She was about to ask him what he meant when he smiled. It was a smile full of teeth, and they were extraordinary teeth. For a moment she thought that no two of them were alike: there were gold teeth, silver teeth, big teeth, broken teeth and even, she was sure, a glass tooth. She wanted to ask Banks about the glass tooth but decided that it could wait.

“Are you hungry?” asked Banks.

Garland nodded. She was very, very hungry.

“Come on, then,” said Banks, and almost dragged her out of the seat.

He strode up to the connecting door. Garland hesitated.

“Come on,” he repeated.

“I don’t know what’s through there,” she said.

“I do,” he said. “I live there. Been living there since – since I got there. It’s a good room. Got food.”

“Food is always good,” Garland admitted. Later she would regret this remark.

Banks pushed open the door between the two carriages and held it for her, a gigantic gentleman.

“Wait,” she said. She went back down the carriage and, stopping in front of each of the fifteen dead, closed their eyes for them.

She walked back to Banks.

“I don’t know what else I can do.”

“Nothing anyone can do,” he shrugged, and stood back to let her pass into the next carriage.

The next carriage was the buffet car.

“Of course,” said Garland. “Where else would food be on a train?”

It was quite a nice buffet car. There was even a table with four fixed chairs beneath it. There was a counter, and a coffee maker, and a refrigerated display cabinet, which was empty. Garland felt her stomach tremble, as if with disappointment.

“I thought you said there was food here,” she said, slightly sullenly.

“There’s food,” said Banks. He reached up and opened a door in an overhead compartment above the counter, and then pulled down a plastic crate, which he set down with a thud on the table. Inside the crate were about twenty small tin cans, each fitted with a large ring pull.

Garland picked one up. The label had no writing on it, just a drawing of a large green circle.

“Apple,” said Banks. He picked up another can, this one with a purple circle on it.

“Plum,” he said. The next can had a yellow circle on the label.

“Banana?” asked Garland.

Banks shook his head.

“Cheese,” he said. He pulled the ring and showed the inside of the can to Garland. It appeared to be a solid, rubbery piece of cheese that had somehow been got into the can.

“Is all the food in cans?” she asked.

Banks looked away. “No,” he said.

“What is it? What’s wrong?”

Banks opened a door below the refrigerated cabinet. Cold steam billowed out from a small freezer compartment. Garland went over and stuck her hand in. She pulled out a cold package, vacuum-sealed and opaque.

“Have you got a knife?” she asked Banks.

“Don’t!” he said. There was fear in his voice.

Garland rubbed the outside of the packet with her finger. Then she dropped the packet and stepped back in alarm.

Inside the packet, set into a flat piece of flesh, was an eye.

“I told you,” said Banks, as he picked up the packet and dropped it back into the freezer compartment.

“What the hell is that?” she said.

“Same as it says on the packet,” Banks said. “Eye.”

“Is it a medical specimen?” she said, disbelieving. “Is it – food?”

Banks shrugged. “Buffet car,” he said. “Must be food for someone, if not something.”

“Jesus,” said Garland, and sat down. “Is there anything to drink here?”

Banks shook his head. “Don’t know,” he said.

“Shame, I could do with a drink,” said Garland (do I drink? she thought) and got up on a chair. She reached into the compartment and pulled out another crate. It slammed onto the table.

“Same as the first,” Banks said. “They’re all the same. Apple, plum, cheese, other food. You want drink –” and he indicated the counter, “– look under there.”

Under the counter was a metal box. Someone, she presumed Banks, had prised it open. Inside were a few small cardboard cartons with tiny straws taped to them. These also were decorated with green circles and purple circles (but not, Garland was relieved to notice, yellow circles). There were one or two small cans of what Garland guessed was soda. And there were several tiny bottles, each labelled with a word. Garland couldn’t read the words without her head hurting, but she recognised the colours of the liquids inside the bottles.

“Thank goodness,” she said, and unscrewed the top of the first bottle. She drank the contents down in one sudden gulp.

“Good?” asked Banks.

A puzzled look appeared on Garland’s face, which was then replaced by anger.

“The fuckers,” she said, slowly.

“What’s wrong?” Banks said as Garland snapped open a second bottle and downed it.

“I can just about cope with not being able to read,” she said slowly and with fury in her voice. “But this is an outrage.”

She opened a third miniature. This time she spat out the contents.

“Is it unpleasant?” Banks asked.

“Unpleasant?” she said. “If it was that, at least I’d be getting something from it. This – this is nothing.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“That’s because you don’t drink. This stuff – there’s nothing to it. There’s nothing in it. Nothing I can taste, anyway. The one thing in this stupid place that I could really do with right now and it doesn’t work.”

She grabbed a handful of bottles and threw them at the wall.

“It doesn’t work!” she shouted.

Banks looked at Garland as she hunched her shoulders and began to cry.

“I think you have a drinking problem,” he said.

* * *

Garland tidied up the mess as Banks put together a colourful meal from the tins. There was a microwave oven behind the counter and he made them bowls of cold plum with hot apple sauce, followed by slices of tinned cheese. It was a surprisingly pleasant and warming meal, and Garland felt better immediately she had eaten it.

“Thank you,” she said to Banks. “I’m sorry about earlier.”

“This is a strange life,” said Banks. “It’s OK to react to things.”

“Let me wash up,” she said, and took the bowls from him.

There was a bathroom, and when she had washed the dishes in the sink, she used the toilet, which seemed to be amply stocked with toilet paper, at least for a train bathroom.

“Time to get cleaned up a little,” she said, and ran some hot water to wash her face. It was only then that she noticed the difference between the bathrooms. This one had a mirror over the sink.

Garland looked in the mirror. She saw a young woman with light-coloured hair and greenish-brown eyes. The eyes looked tired and frightened.

“So you’re Garland,” she said to her reflection. “Nice to meet you.”

Let’s hope so, her reflection beamed right back at her.

“Yeah,” Garland said, “I know exactly what you mean, Garland. Now let’s go.”

* * *

When she got back, Banks was sitting at the table.

“You look a lot better,” he told her.

“Thanks,” she said.

“Before,” he went on, “you looked horrible. Dirty and awful. But now you look OK.”

“Great,” she said. “You look amazing, too. Now shall we get on?”

Banks looked surprised. “Get on what?”

“What, you just want to sit in here eating canned cheese all the time?”

“I have been doing that so far,” said Banks. “Hasn’t done me any harm.”

“Well, something has done me harm,” Garland said, “and I would like to find out what it is, and why it is doing it.”

“OK,” said Banks. “I’ll give you some cans.”

She looked at him.

“You’re not coming with me?”

Banks shook his head.

“I like it here,” he said. “I’ve got light, heat… I’ve got cans.”

“All the basics,” she said. She looked at Banks. He was sitting in a semi-foetal position, his arms clutching his knees. For a giant, he looked very frail.

“You’re frightened,” she said, and regretted it instantly. Banks looked angry.

“I know I am,” he said. “Because this is a frightening place.”

“But you can’t stay here,” she said.

“Of course I can,” he said.

“What about when the cans run out?”

“There’s always…” Banks nodded at the refrigerated drawer.

“You can’t –”

“How do you know?” Banks was getting agitated. “How do you know what I can’t do? Or what I can? Because I don’t know, so how can you?”

He put his face between his knees and, to her surprise, began to heave his huge shoulders back and forth.

She was about to ask Banks if he was being sick when a thought came into her mind:

He’s crying. That’s what he’s doing. He’s crying because he’s very upset.

Garland went over to Banks and sat next to him. She wasn’t sure if she should touch him or not, so she slid her arm through the crook of his enormous long leg and held his calf. It felt, even to her, like an odd thing to do, but she couldn’t think of anything else and, besides, it seemed to calm Banks, whose heaving subsided like the receding aftershocks of a small earthquake.

“Where are we?” he said. “What’s happening? Why don’t I know anything?”

Garland let out a sigh.

“I’ve said it before and I’m sure I’ll say it again,” Garland replied. “I don’t know.”

Banks wiped his face and she realised she had been right, and he had been crying.

“When I was… somewhere else, I don’t know,” he said, “I read, or I was told, that not knowing anything was a good thing. Like children don’t know anything, and that makes them better than us, because we know things, bad things.”

He gazed at her. His eyes were deep and wet from the crying.

“‘Suffer the little children to come to me’,” he said. “Only suffer doesn’t mean suffer.”

Garland looked around. She thought of the eye in the freezer drawer.

“What does it mean, then?” she said, and got up.

* * *

Banks watched as Garland collected a few supplies.

“Where are you going?” he said.

“That way,” she said.

“You don’t know what’s up there,” he said.

“No, but I know what’s back there,” she replied. “Dead people and darkness.”

“Could be the same the other way too.”

“I know that. But I’m not sitting here for the rest of my life.”

Banks looked at her.

“I’m not a coward, you know,” he said.

“I didn’t say that.”

“It’s just – I know where I am here. I know what’s going on. If I go with you –”

“Sure. I get it.”

Suddenly the lights went out. Banks shouted in alarm. Garland dropped down beside him.

“Don’t move!” she hissed and grabbed his arm.

She had no idea why she had told him not to move, but she remained there in the dark and stayed silent.

After a while, Banks whispered, “Are we waiting for something to happen?”

“I don’t know,” she admitted.

“Then can we –” Banks began, when a screeching noise filled the air, like an entire wall of metal being torn in half. Garland felt Banks curl up beside her, and she wanted to do the same but something inside her would not let her move. Instead she remained half crouched as the screeching got louder and louder.

The darkness inside the compartment was total, but outside she could see tiny lights, miniature stars exploding in the gloom of the night. The stars burst and vanished like bubbles made of light, illuminating for a second or two and then disappearing back into the darkness.

As the noise got louder, Garland saw that the lights seemed to be getting bigger, or nearer, she wasn’t sure which. Now the noise was so loud that Banks was also screaming, whether in distress or physical pain she couldn’t say. The lights were flashing pools of colour: whatever they were made by was all around now, wave after wave of exploding splashes of illumination that reminded Garland, crazily, more of jellyfish than stars.

She barely had time to marvel that she could remember what a jellyfish was when, with a firework’s fizz, one of the lights exploded right outside the window. Banks screamed and clenched himself into a tight mass as ball of light after ball of light slammed against the windows. The screeching now was a high-pitched intolerable whine as the balls of light increased in size and frequency, until soon the carriage was drenched in a constant unceasing barrage of light and sound. Garland closed her eyes and tried to block her ears, but still the noise and light got in. She could feel Banks shaking next to her, and she was about to risk her own sight and hearing and put her arms round him when, as abruptly as it had started, everything stopped.

* * *

They sat for a while, not moving, not sure if it was going to start again. The carriage lights came back on, accompanied by the faint hum of the refrigerated cabinet. Whatever it was, thought Garland, must have generated a field that stopped the power to the carriage.

Slowly, Banks stopped shaking.

“Are you OK?” she asked him.

“I’m coming with you,” he said.

* * *

Banks insisted on returning to the dead compartment. He returned with the soldier’s kitbag, which he filled with cans.

“You need to kick that habit,” Garland said.

Banks shook his head

“Cans are everything,” he replied, and hoisted the kitbag over his shoulder.

Garland looked around to see if there was anything else worth taking. She found a drawer in the counter which contained some paper clips, a few pens and a small pad of paper covered in figures.

“Looks like this was a real train at some point,” she said. “These must be price calculations.”

“Interesting,” said Banks. “What’s that?”

Garland looked down. Something had rolled out from the back of the drawer. It was a keyring. On it were a couple of small keys and a miniature torch. She flicked the switch.

“It works,” she said, and put it in her pocket.

* * *

Banks led the way to the end of the carriage. Garland looked at the door. “Onwards, I guess,” she said.

Banks gripped the door handle.

“Ready to leave home?” she said.

“No,” said Banks, and opened the door.

* * *

As they stepped into the next carriage, they were met by a gust of cold air. Banks and Garland moved forward with difficulty, because the windows of the carriage had been either removed or stove in, and a freezing wind buffeted them from either side.