Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

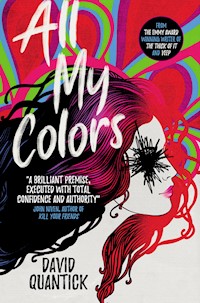

"David Quantick is one of the best kept secrets in the world of writing. He's smart, funny and unique. You should let yourself in on the secret." – Neil Gaiman It is March 1979 in DeKalb Illinois. Todd Milstead is a wannabe writer, a serial adulterer, and a jerk, only tolerated by his friends because he throws the best parties with the best booze. During one particular party, Todd is showing off his perfect recall, quoting poetry and literature word for word plucked from his eidetic memory. When he begins quoting from a book no one else seems to know, a novel called All My Colors, Todd is incredulous. He can quote it from cover to cover and yet it doesn't seem to exist. With a looming divorce and mounting financial worries, Todd finally tries to write a novel, with the vague idea of making money from his talent. The only problem is he can't write. But the book – All My Colors – is there in his head. Todd makes a decision: he will "write" this book that nobody but him can remember. After all, if nobody's heard of it, how can he get into trouble? As the dire consequences of his actions come home to both Todd and his long-suffering friends, it becomes clear that there is a high – and painful – price to pay for his crime. "A morality tale, a comedy, a horror story rolled into one. All My Colors has it all." – The Sun "Really rich, funny, unsettling and just very alive. A brilliant premise executed with total confidence and authority." – John Niven, author of Kill Your Friends

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 347

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by David Quantick and available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One

One

Two

Three

Four

Part Two

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Epilogue

About the Author

Also by David Quantick and available from Titan Books

Night Train

(April 2020)

TITAN BOOKS

All My ColorsPrint edition ISBN: 9781785658570E-book edition ISBN: 9781785658587

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UPwww.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 201910 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2019 David Quantick

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Fub

PARTONE

ONE

It was a Saturday night in March of 1979 in DeKalb, Illinois, and Todd Milstead was being an asshole. Not that Todd Milstead wasn’t being an asshole every night of the week, but this particular night he was giving free rein to his inner dickhead. All the pointers had been in place from the off: there was booze, there were other writers present (although “writers” was pushing it), and Todd’s wife Janis had made the dinner and taken the coats, so Todd reckoned everyone there was on his turf as well as his dime (although Janis’ money from her late dad—who also gave them the house—had paid for the dinner).

So, Saturday night at the Milsteads’. Janis, in her best dress and her hair done nicely because even when there was no point, Janis made the effort. And Todd, looking like a youngish Peter Fonda, with a strong manly chin and twinkling masculine eyes and hair just the daring side of long, smoking a lot of cigarettes—he’d wanted a pipe, but Janis kept laughing whenever Todd affected a stout briar and if there was one thing Todd couldn’t abide, it was being laughed at—and holding a big tumbler of Scotch, because he liked the feel of the heavy square glass and because Scotch was a real drink.

And that was Saturday night at the Milsteads’; Janis bringing in the bowls and the plates and Todd holding forth. On Kissinger, on Farrah Fawcett-Majors, on Superman, on Carter, and on books. Always on books. The men who called themselves writers and met at Todd’s on a Saturday night were a mixed bunch in the way the people crammed into an elevator that is plunging ten floors into a basement are a mixed bunch. They had one thing ostensibly in common—the writing, the being trapped in a falling elevator—but what they really had in common was that they were a totally disparate bunch of losers all screaming, “Get me out of this elevator!” And nobody was listening. Especially not Todd. Todd never listened. Somebody—Joe Hines, one of the people trapped in Todd’s elevator—once said that the only way you could get Todd to listen would be if you taught a mirror to talk, and even then, Todd’s reflection wouldn’t be able to get a word in because Todd would be lecturing it on the best way to be a reflection.

Not that Joe ever said this to Todd. Nobody ever said anything to Todd. As another one of the gang, Mike Firenti, said, you went to Todd’s for the booze and food and not the monologue, but the monologue was the price of admission. None of Todd’s friends, if friends was the word, had enough money to indulge in blowouts of their own.

Joe’s normal experience of a Saturday night was two beers in front of the TV and a desultory jack-off, while Mike’s was slightly better in that he could go to his sister’s and drink his brother-in-law’s beer while his brother-in-law talked about ice hockey, a game Mike didn’t even know existed until his sister got engaged. Billy Cairns was worse off. Billy had nearly been something in the 1960s: he’d had some stories printed in a science-fiction magazine, and he’d started a novel, but then the mag went bust and the novel got lost somehow and Billy started drinking. Billy spent his nights in front of the TV staring at reruns of Star Trek and sometimes his breath smelled of cat food. Saturday night at Todd’s was better than Saturday night not at Todd’s. There was food, and booze, and Janis, who looked great in a mail order catalogue dress, and sometimes there was even, when Todd was feeling indulgent or had just passed out from booze, conversation.

And sometimes there was Sara Hotchkiss. Sara Hotchkiss was married to Terry Hotchkiss. Terry managed a supermarket outside town, and the times he attended Todd’s parties his contributions were minimal. This was because Terry liked to talk about the supermarket to the exclusion of all else, and on occasion had been known to get heated about marrows. For this reason and others, Sara generally arranged for Terry to drop her off outside the Milsteads’ house and collect her later, an arrangement which suited nearly everyone. (Sara didn’t come to Todd’s gatherings every week, because Terry liked her to entertain his suppliers when they came over for dinner and because she had a feeling that Janis didn’t like her. She’d be at the Milsteads’, and Janis would pass her the dip, and she’d look at Janis and know that Janis knew, and feel contempt for Janis for not smashing her face into the dip, and contempt for herself for not smashing her own face into the dip. But Janis never said anything and Sara never said anything and it was pretty good dip.)

So, it was a Saturday night in March of 1979 in DeKalb, Illinois, and ‘Heart Of Glass’ by Blondie was number one in America, and Terry Hotchkiss was entertaining clients, so it was just Joe, Mike, and Billy Cairns, and Janis. And Todd Milstead, who was being an asshole.

“Bullshit!” Todd shouted. “Bullshit!”

Janis moved his glass to a side table. Todd reached down and picked it up again. “That is such bullshit!” he said before swigging the whiskey down in one sloppy gulp. He put the glass down, making a visible dent in the table.

“All I said,” protested Joe Hines, “was that Mailer’s day is over.”

“Over?” mocked Todd, whose knowledge of Norman Mailer was overshadowed by his fondness for any aggressive writer who liked boxing and his own penis. “Mailer’s never had his day. His day hasn’t even begun!”

“It’s been years since Mailer wrote anything decent,” said Mike. “That piece in America magazine…”

Todd Milstead actually sneered. It was a real Victorian sneer, the kind that went best with a pair of carelessly twisted mustachios. Todd’s sneer said, I am going to demolish you for that opinion. It also said, because for once I know what I’m talking about.

“Norman Mailer has been an American institution for so long that he’s starting to come over like another kind of American institution,” said Todd with his head tilted back and his eyes half shut.

“Oh shit, he’s quoting. I love it when he does this,” said Joe, omitting the second part of his thought, which was: “to someone else.”

“Said institution being the electric chair,” intoned Todd, “into which some of us would rather be strapped than endure another line of Mailer’s unfortunately deathless prose…”

He stopped. “Is that the piece you mean?”

“I guess so,” said Mike. “But that’s not the part I mean. I was referring to the quote from Mailer himself where he says—”

“Writing books is the nearest men come to childbirth—that quote?” said Todd. “I am the embodiment of the American novel—that quote? Tell me which one you mean. Because,” and Todd tapped his forehead, “I got ’em all in here.”

Janis, returning to collect some cigarette-butt-filled plates, made a mental note. If Todd was starting to boast about his powers of memory, that meant the evening was either going to wind down or get nasty. Not that the two were connected—although Todd Milstead’s tendency to use his eidetic memory as a weapon could be a fight starter—but when Todd started boasting, he also started getting personal. She removed the more fragile glasses from the room.

“I can’t remember ’em all like you can,” said Mike.

“Yeah, Todd,” said Joe. “You have to give us mere mortals some leeway here.”

Todd, like all egoists, was incapable of extracting irony from anything that resembled praise. He got up and nodded.

“Time for a piss,” he said. “Mailer!” he added scornfully, and left the room.

There was some silence. The three men drank their decent whiskey.

“You know,” said Billy. “This morning I saw the strangest thing.”

The others waited. It was a bad idea to interrupt Billy’s stories, because it only made them longer and because he was so good at doing it himself.

“Or was it Tuesday?” said Billy.

“Jesus, Billy,” muttered Mike. “What are they putting in cat food these days?”

“Anyway,” said Billy, “I was in the store when this woman comes in. About thirty, thirty-five, kind of attractive though, blonde hair, and she says to Jimmy, he owns the store, nice man, sometimes lets me use the bathroom…”

“Billy,” said Joe, a warning note in his voice as Todd returned, his pants spotted with piss.

“Okay,” Billy said. “She says to Jimmy, I’d like to buy a hacksaw. How big, says Jimmy, and the woman says, I don’t know, just big enough to get this off. And she holds up her finger. Third finger, left hand, the wedding ring finger.”

“What?” said Joe. “She wanted to cut off her wedding ring?”

Todd came back in and sat down with a thud.

“No,” said Billy. “That’s what Jimmy said. But there’s no ring there. She says, I want to cut off the finger. In case I’m ever stupid enough to get married again. No ring finger, she says, no ring. No ring, no wedding.”

“I don’t believe it,” said Mike.

“I was there,” said Billy. “Jimmy told her he couldn’t be of assistance, but it happened. I was there.”

“Billy,” Todd suddenly said. “Billy, tell the truth.”

“I was there,” Billy protested. He cast an involuntary glance at his whiskey. “I was there,” he repeated.

Joe and Mike looked uncomfortable. It wasn’t nice to be baited, but baiting Billy… there were unspoken rules about that. Nothing personal was one rule. And it looked like Todd was about to break it.

“’Fess up now, Billy,” said Todd. He said it gently and that was worse.

“I was there,” Billy repeated. “Jimmy was behind the counter and the woman came in and I was at the counter too and it happened.” He was close to tears now. “You can ask Jimmy if you like.”

He stopped. For a moment, there was doubt on his face, the look of a man who fears that nothing he says can be corroborated.

“I don’t need to ask Jimmy,” said Todd. “I just need to open a book.”

He sat back and looked at Joe and Mike. They didn’t respond.

“Oh, come on!” he said. “The woman who goes into a store and asks for a hacksaw to cut off her ring finger?”

“That’s what Billy said,” Joe said cautiously.

“She wants to cut off her ring finger to make sure she won’t get married again?” said Todd. “None of that sounds familiar to you?”

“No,” said Mike.

“Nor me,” Joe said. Billy said nothing. He was biting his lip.

“It’s fucking famous!” shouted Todd. “It’s the opening scene! The first paragraph!”

He looked at their blank faces. Janis came in from the kitchen, as she always did when the real shouting started.

“Oh my God,” Todd said shrilly. “None of you knows what I’m talking about, do you? You haven’t the foggiest fucking idea.”

“We should continue this another time,” said Joe, who felt he’d had enough. It was difficult listening to Todd like this when you had some idea what he was talking about. This was worse, because it was incomprehensible as well as unpleasant. “Mike, can you give Billy a ride, you’re nearest.”

Todd stood up. He tilted his head back.

“Hesitantly, the store clerk repeated to the woman what he thought he’d heard her say. ‘You want to buy a handsaw so you can cut off your ring finger?’ he said. ‘That’s right,’ said the woman, and what scared the clerk was how calm she sounded. ‘I can’t do that, ma’am,’ said the clerk and, because he was a fair man, he added, ‘And what’s more, I’m going to telephone to all the other stores around here to alert them concerning your attempted purchase.’”

Todd ceased reciting. He looked at the blank faces staring back at him.

“Jesus,” he said. “You call yourselves writers.”

He turned to Janis.

“You know it, don’t you?”

Janis, startled to be asked her opinion, stammered out a no.

“Right. Okay. Not one of you has read, or heard of, All My Colors.”

“All my what?” said Mike, emboldened by the room’s general ignorance.

Todd turned to him. “All My Colors, Mike. All My Colors. By Jake Turner.”

More blank looks.

“Oh, don’t tell me you haven’t heard of Jake fucking Turner,” said Todd, his voice a weird mixture of sarcasm, contempt, and genuine bewilderment. “I mean, Joe, Mike, sure, your knowledge of literary history is woeful, but Billy…”

Billy looked up, fearfully.

“Jake Turner, Billy. He was a Kerouac junkie just like you, am I right?”

“I don’t know of him,” said Billy.

“Christ,” said Todd. “Jake Turner!”

He addressed the room.

“All My Colors, Whitney Press, 1966. It was in the New York Times top ten list for two years. And not one of you has heard of it.”

Todd sighed. He’d done enough for art and literature for one evening. And he was tired. Tired of being the smartest guy in the room. Tired of being surrounded by the ignorant.

“Get out,” he said, waving a dismissive hand.

Janis hurried everyone to the door, and no one lingered.

* * *

“You think I was too hard on them?” said Todd as he brushed his teeth at the bathroom mirror.

Janis was trying to unzip her own dress because if Todd did it, he’d break it.

“You’re always too hard on them,” she said. Todd heard it as praise.

“Maybe,” he said. “But tonight, goddammit, that was classic. I mean, I expect you not to know it —you’re all magazines and coffee table books—”

Janis, who always had a three-deep pile of library books by her bed, said nothing.

“But those guys… No wonder everything they write turns out shit.”

Janis managed to slip out of the dress without tearing it.

“How’s your book coming on?” she asked mildly.

Todd, immune to even the strongest sarcasm, frowned. It was a frown designed to invite sympathy and, even though it never achieved its purpose, Todd retained the habit.

“Oh, Jesus, it’s hard,” he said. “Sometimes the words flow like a tidal wave, and sometimes it’s like God turned the stopcock off at the wall.”

In fact, he thought to himself as Janis carefully replaced the catalog dress on its hanger, most times it’s like that.

“I’m going to sleep in the spare room tonight,” said Janis. “Early start tomorrow.”

Todd nodded absently, unaware that Janis was trying to spare herself a night of him snoring, shouting in his sleep and whacking her in the face with a flailing arm. In fact, he was barely aware that Janis had left the bathroom.

Not for the first time, Todd Milstead was thinking about a book.

* * *

Janis woke up. A thumping noise was coming from downstairs. A repetitive, low thumping noise, like someone banging shot glasses onto a wooden table or—and for a moment an almost hopeful vision filled her mind—like someone repeatedly shoving her husband’s face against a door. She got up, found a long and heavy flashlight under the bed, and, putting on a dressing-gown, went downstairs.

The door to Todd’s study was open (he called it a study, but as all he ever did was read Penthouse in it, Janis thought of it as his jerk-off room) and the light was on. Janis approached it, trying not to be scared. As she did so, she could hear swearing.

“Motherfucker!”

It was Todd. She relaxed from the relief, but now she found that she was angry. He knew she was up early the next day. And here he was, up in the middle of the night, making an awful racket. Janis was very tired and suddenly it all seemed too much.

She went into the jerk-off room. Todd was standing by his bookcase. The house was full of bookcases, but this was Todd’s special bookcase, where he kept the Good Stuff. Todd even called it the Good Stuff, like it was fine liquor and all Janis’s dumb paperbacks (he never used the word in front of Janis, but then he didn’t have to: she knew) were rotgut. Rotbrain, she found herself thinking as she stood in Todd’s study, watching Todd attack his own bookcase. Now she could see the cause of the noise that had woken her: Todd was pulling books out and throwing them at the desk—thud! thud!—like a maniac.

“What are you doing?” she said.

Todd whirled around. “You startled me,” he said accusingly.

“You woke me,” she countered. “Todd, it’s two in the morning.”

“Now we’re a clock,” said Todd, which Janis thought made little sense. “I know what time it is, Janis.”

“Go back to bed,” she said. “You’ve got—”

Janis couldn’t for the life of her think what it was that Todd had to do the next morning. Pull his pud until lunch, no doubt.

“Stuff,” she said. “Todd, it’s too late for this.” “What do you mean, it’s too late?” he slurred, and Janis realized that Todd had started drinking again after she’d gone to bed. She was very tired. Bone tired and brain tired.

“Todd, I asked you once already,” she said. “What are you doing?”

Todd thudded a few more books at the desk. Janis saw a second edition Bellow crease and fall to the carpet.

“I’m looking for that fucking book,” he said.

“What—” said Janis. Then she realized. “That book.”

“Yeah, that book,” said Todd. “I figured it out. You jerks.”

He sniffed. Oh great, Janis thought, he found some coke. Cocaine was hard to find in their small town, but Todd could be quite determined when it came to himself and his needs, as he was now proving.

“What do you mean, you figured it out?” Janis sat down. She would rather have lain down, but the floor was stiff with literature.

“You all got together,” said Todd. “One of you had an idea, to torment old Todd. Pretend you never heard of All My Colors or Jake Turner. So, you got Billy to tell that story—although knowing Billy, the poor ass probably thinks it really did happen—for bait, and then you all pretended you didn’t know the book. Messing with my mind.”

“I have never heard of that book,” said Janis. “Honestly, Todd. Now please stop and go to bed. You’re—you’re tipsy, and somehow you think this thing is real. It’s not real, Todd.” Like talking to a child who was having a tantrum, she thought.

“If it’s not real,” said Todd, staggering past a Herman Melville, “then how come I remember it?”

And, before she could stop him, he tilted his head back (did he need to do this to remember things, Janis wondered, or was it another affectation) and began to recite:

“At first, she thought she must be the luckiest woman alive, but as time went by, Helen came to realize that she was anything but that. Luck, the good kind anyway, was a commodity she was desperately in need of but forbidden, like a patient in hospital refused the one drug that might cure her.”

Todd looked at Janis, his lips flecked with spit (or cocaine, she thought).

“Did I make that up, Janis?” he said. “Did I just make all that up?”

Janis looked at Todd. Suddenly, out of nowhere, a crossroads in her life was looming up. She wasn’t sure if she was at the crossroads yet, but she could see it. It didn’t look like a threatening crossroads either, the kind with a gallows at the roadside and the devil next to it. It looked like a promising sort of crossroads. But she wasn’t there yet.

Not quite.

“No, you didn’t make that up,” Janis said. “Because it was quite good.”

Todd glowered at her.

“Not great, I grant you. But it was quite good.”

Todd’s eyes seemed to glow. His face certainly did, fire engine cherry red. He took a step forward. He raised his hand.

Janis also took a step forward. She took Todd’s hand.

“I want you to stop acting like a jerk,” she said. “I want you to be my husband, and be an adult. And—”

She let go Todd’s hand and it fell to his waist.

“—I want you to stop screwing Sara Hotchkiss.”

Before Todd could reply, Janis had walked out of the room. She didn’t sleep long that night—it was nearly three now—but she slept well.

* * *

Sunday was a quiet day at the Milsteads’. Janis cleared up the mess in the living room and was going to leave the dirty glasses and crockery for Todd when she realized he’d be so hungover that he’d probably smash everything to pieces. So, she compromised: she cleaned up everything but Todd’s study. If he wanted to wade ankle-deep in the great American novel, that was up to him.

After she’d cleared up, she went to visit a gallery with a friend, and came home about four to find that Todd had shut himself in his study and was—by the sound of it—making notes on his new book. She knew when he was making notes because he would spend hours getting everything just right—finding the perfect pencil, sharpening it, getting out his yellow legal pad, aligning everything so it was parallel to the sides of the desk—and then do jack shit until dinnertime.

* * *

The evening passed without incident. Janis and Todd watched TV in uncompanionable silence. Every so often, Todd would look at her with a puzzled expression as though he had something important to ask her, like where do baby rabbits come from or how do I get red wine stains out of a white carpet, but then his face would go blank and he’d stare at the TV again.

Next morning Janis was out bright and early to buy groceries. Todd was up neither bright nor early but he too had somewhere to go. After a light breakfast of cornflakes and toast (he had never got around to discovering how eggs worked), he drove into town in his old Volvo. In a perfect world, Todd would have owned a Porsche but that wasn’t going to be happening any time soon, and beside he liked the Volvo because it was Scandinavian like Ibsen or something, and it looked like the kind of a car a writer would drive.

Todd rarely made trips into town. Janis ran all the errands and did the shopping, and Todd met Sara in motels out by the highway. Sometimes Todd might have a night with the gang in a local bar, but money for booze came from Janis (her dead old dad still holding the purse strings) and bartenders didn’t like it when Todd started shouting. But today was special; today was writerly. Todd was going to the local bookstore.

Legolas Books was small, cramped, and unpopular, but Todd liked it. Timothy, the owner of Legolas, was a former hippy who’d taken advantage of premature baldness and myopia to remodel himself as an archetypal bookstore-owner, complete with bald head, gold-rimmed glasses and the benevolent look of a man who has lived his life among books rather than taking too much acid. His devotion to the wholesale faking-up of whatever a bookstore should be—shelves in disorder to create the impression of too many books, cups of awful coffee to encourage chats, unnecessary step ladders and a framed, hand-written copy of the Desiderata— had extended to his own attire of moleskin waistcoat and collarless shirt. Anywhere else, Timothy would have been roughed up and thrown into a storm drain, but here in his book-lined kingdom, he could be himself with impunity.

Timothy’s attitude to literature appealed to Todd, who had himself been faking a life in books for some years. Todd was particularly drawn to Timothy because the shine-pated bookseller had decided for some reason that Todd was a real writer, in the same way that Timothy was a real bookman. They could stand for hours, Todd and Timothy, on either side of Timothy’s counter, discussing books and their contents until finally interrupted by an angry cough from some idiot who wanted to actually buy a book. Timothy didn’t mind at all: he knew that Todd was as likely to write a great novel as he was to piss diamonds, but Todd was part of the bookstore’s color. “See that fellow, browsing among the Hemingways?” he’d say to a tourist who’d come in to buy a map, “Local author. We’re kind of proud of him.” And the tourist would feel ashamed at not being more artistic, and buy something expensive by a dead guy.

Today as usual Timothy was behind the counter, or rather beside it, sitting on a high stool, nose in a book, ready to peer over his glasses at any approaching customers. When the shop bell rang as Todd entered, Timothy closed the book without marking his place—it was, being the first book he’d picked up, an empty notebook with an attractive marbled cover and as such had no actual words in it—and greeted Todd.

“Good morning, scribe,” he said. “How fares the struggle?”

Even Todd would normally have had difficulty responding to this without headbutting Timothy, but today he was hardly listening.

“Got a specific request for you today,” he said.

“Well,” said Timothy, “like it says in the men’s room—‘We aim to please. You aim too, please.’”

He beamed at his salty sally. Todd just looked at him. What the fuck was the old prick on about?

“I need a copy of All My Colors,” he said.

Timothy looked confused.

“I don’t think I recollect that one,” he said. “Is it new?”

“Oh, not you as well,” replied Todd. “Has my wife been down here, is that it?”

“Your wife?” said Timothy. “No, haven’t seen Janis since your last birthday. She came in and bought that facsimile copy of Tropic of Capricorn for you.”

“You sure?” said Todd, a hint of menace in his voice.

“Yes, I’m sure,” Timothy said, more firmly. He might be an old fraud, but he was also a nasty heartless old fraud and Todd didn’t exactly scare him. “Now what was the name of that book again?”

Todd backed down. “Sorry, Timothy, I’m having a weird time lately.”

Timothy was about to tell Todd that the times they were a-changing when he realized that this was a heap of bullshit too far, even for him. Instead he said, “Just tell me the name, author and publisher and let’s see if we can track that bugger down for you.”

* * *

A few minutes later, having searched the FICTION shelves, both hardback and paperback, Todd and Timothy were in the stockroom. A bare bulb shone above them and Timothy was consulting his ledgers.

“Nothing,” he said. “Not the book you wanted nor anything by this Jake Turner.”

Todd grabbed the ledger from him. Timothy took it back.

“I know my own stock,” he said. “And I know books. If you weren’t so darned fervent, Todd, I’d be so bold as to say that there ain’t no such book.”

But I’ve seen it, Todd wanted to say. I recall the cover—it’s a woman’s head, and she’s looking out of the cover, and her hair is like a hydra’s. No, he corrected himself. It’s a rainbow. It’s all her colors. Kind of literal, but it works. Todd found himself remembering more lines from the book. Dialogue. Plot. Even chapter titles. He said none of this to Timothy. He didn’t want the Mayor of fucking Hobbiton telling people that Todd Milstead was losing his mind.

“Okay, Timothy,” he said finally. “I guess I got it mixed up with some other book.”

“I guess you did at that,” said Timothy. “I’ll keep an eye out for it, Todd, and anything else by this Turner fellow, and call you if something turns up.”

Somehow Todd knew that nothing was going to turn up, just as he knew that there would be no copy of All My Colors or any other books by Jake Turner at the local library, or the main library in the city, or the new giant bookstore out of town, or anywhere in the world. But he also knew that All My Colors was real, that he’d seen it, he’d read it, he’d owned it, for Christ’s sake. He couldn’t understand how two entirely different things could be true, but they were, and there was nothing he could do about it.

“See you ’round, Todd,” said Timothy as Todd headed out the door. He picked up his empty but beautifully bound book. Stupid fucker’s finally gone crazy, he thought to himself as he flicked through its blank pages.

* * *

If Timothy could have seen Todd forty-five minutes later, he would not have changed his opinion. Todd was sitting in the driver’s seat of the Volvo, both hands clamped onto the wheel, and he was talking to himself. He had been talking to himself since he’d got into the car half an hour ago and he showed no signs of stopping.

“Chapter Two,” Todd was now intoning, “A Sunrise and a Sunset.”

His eyes were focused on the car’s immobile windshield wipers, but they weren’t seeing anything.

“Helen woke that morning with a feeling she could not explain,” Todd told the windshield wipers. “She could not tell if she had ever felt like that before, but as she could no longer remember feelings or anything that wasn’t part of her daily routine, this was not surprising…”

He stopped. A woman, passing in front of the car with her child in a shopping cart, was staring at him. Todd looked at himself in the rearview mirror and saw what the woman saw: a staring-eyed maniac, holding the wheel of a car that wasn’t moving, and talking to himself without stopping. Todd stared back until she moved on, saying something to the child. Then he addressed the mirror.

“What the fuck,” he asked, “is in me?”

* * *

What the fuck is in me? It was a question Todd couldn’t stop asking himself all the way home. The answer was simple. It was a book, called All My Colors, by a man called Jake Turner, only the man didn’t exist, and nor did the book. He was going to go through all his encyclopedias of literature and dictionaries of biography and copies of The Writer’s Gazette and if necessary the Yellow Pages, but he already knew what he would find. Nothing. There was no such writer as Jake Turner, and there was no such book as All My Colors.

So what the fuck is in me?

* * *

Todd got home, threw the keys in the wooden bowl by the door—once he’d dreamed of beautiful undergraduates and even the occasional professor’s wife doing the same, at swinging parties where everyone drank Todd’s whiskey and laughed at his jokes and Todd always went home with the most beautiful wife, but Todd never got a professor’s job because he’d never been published, and wasn’t that a loaded word. But anyway, it was a nice bowl—and went into the kitchen to find something to drink. As he opened the fridge, the phone began to ring.

Todd picked up the extension. Maybe it was Timothy, ringing to apologize and offer him a compensatory copy of—

“Todd, this is Sara.”

“Oh, Sara. This isn’t a great time.”

“It never is, unless you’re drunk and I’m naked.”

“Sara, can I call you from my study?”

“No, you can’t. Todd, I just had Janis on the phone.”

“What did she want, a recipe?” Todd almost laughed at his own witticism, then remembered the conversation he’d had with Janis the night before.

“No,” said Sara, “she wanted to tell me to stay away from you. I told her I didn’t know what she was talking about—”

“Good,” said Todd, who had located a carton of V8 but was now thinking of trading up to a beer.

“—but she knew I did, so that was a waste of breath. So, I just let her talk.”

“I bet that was fun.”

“Actually, it was interesting.”

“Janis?”

“What she said. I thought she was going to give me both barrels, and she started out that way, like she was about to scream at me and call me a whore, but then she just went calm.”

“‘Went calm’?” asked Todd.

“Yes,” said Sara. “She went calm. Her voice changed and then she said:

* * *

“I’m not going to warn you off or any nonsense like that. I’m just going to ask you to do me one favor.”

“What?” said Sara, anticipating a Go fuck yourself. Maybe not that: Janis never swore. Go screw yourself, then.

“I don’t see why I should be the one who has to do all the work. I want you to call the house and tell Todd I’m leaving him.”

“You want me to—”

“Yes,” said Janis. “I figure you owe me that at least. Can you do that, Sara? It’s not much to ask after what you did. Call Todd up and tell him I’m leaving.”

“I can do that.”

“Great. Oh, and Sara? When you’ve done that—”

“Yes?”

“Go fuck yourself.”

* * *

“Janis said that?” Todd repeated, amazed. “Janis told you to go fuck yourself?”

“She did,” Sara replied. “But I think she mostly wanted me to convey to you the fact that she is leaving you.”

“Because of us? You and me?”

“No, Todd,” said Sara. “Because of you.” And she rang off.

* * *

Todd sat in front of the TV with a beer. There was nothing on TV but afternoon soaps and even Todd couldn’t make a case for afternoon soaps having stories or characters that any writer could learn from (although one episode of As The World Turns contained more ideas, plot and character development than all of Todd’s unpublished work to date). So Todd sat there, suckling at his beer like a baby, waiting for someone to do something.

Todd liked to tell the gang that there were two kinds of people in the world, those who do and those who don’t. Todd was a do-er and they were don’t-ers. The fact that Joe was a high school teacher, the fact that Mike had two jobs because his mother was in an expensive nursing home, and the fact that Billy was the only one of the gang who’d ever had anything published—these things were irrelevant. There were do-ers and don’t-ers, and Todd was a do-er.

If pressed, and it was his booze so he was never pressed, Todd would have found it hard to produce any examples of doing. Janis cooked and cleaned and dealt with bills and maintenance. Todd had some intermittent income from—yes—teaching writing at the community college, but that had tailed off lately as Todd had a habit of giving outlandishly good grades to the girl students, while simultaneously putting down any talented young males (in this respect, and this respect only, Todd was an early proponent of positive discrimination).

Generally, however, Todd Milstead was not an active man. He had designed his life to be this way, as it gave him more time for writing. The only problem was that Todd very rarely did any writing. He would get up, shower, breakfast, and go into his study. He would organize all his writing materials and sometimes even tidy his collection of authorly items: the framed and signed photograph of John Steinbeck (Todd had bought it at auction and it was signed To Beverley but hey, it was authorly), the quill-and-ink brass paperweight that Janis had thought was cute and bought for him, the inspirational Bob Dylan quote he’d typed out himself and taped to the wall—these were all the tokens of his author-ness, what Todd (but only to himself, which was wise) sometimes liked to call “the handmaidens of brilliance.”

But once this was done, the straightening and the tidying, that was it. Nothing happened. Todd could sit there for hours, waiting for the Muse to strike. But if she was striking, it felt to Todd like she was doing so for few er hours and more pay. Todd waited and waited. He took down books and scoured them for inspiration. He quoted his favorite lines to himself. Sometimes phrases came into his head, and he would start writing them down and expanding them into paragraphs until he realized that he was just transcribing passages that he remembered (he remembered them perfectly, but that wasn’t really the point). And he’d pull the paper out of the machine and screw it up into a ball and throw the ball into the corner with the others, and then he’d pull out a copy of Playboy.

And that would be it until lunchtime, when he’d wander into the kitchen, look at whatever Janis had left him to heat up, and then phone for a pizza because he didn’t cook. Todd was a man who’d always rather someone else did it for him, and now he was waiting for Janis to come home and tell him how his marriage was going to end.

* * *

Janis came home toward the end of Todd’s second beer, which was just as well. If she’d come home during the third beer, conversation—rational conversation, anyway—would have been risky. Todd tended to get angry after beer in the afternoon.

Janis saw the two beers and decided to keep it short.

“Did she call?” she asked.

Todd thought about pretending he didn’t know who Janis meant. Then he thought again, and said, “Yes,” as briskly as he could.

“Good,” said Janis. “Then you know where we stand.”

“I suppose so,” Todd replied. He had no idea in fact where either of them stood, but he was going to let Janis do this for him, and so he kept his answers short.

“This house belongs to me, you know that,” Janis said. “You’re at fault in this situation, I guess you know that too.”

Todd said nothing.

“Any lawyer will tell you that you’ve got no chance of turning this around in your favor, so I wouldn’t waste your breath or your money.”

“We’ll see,” said Todd, and wondered why he’d said it.

“Fine, and good luck with that,” said Janis. “Now. I want you out of here, for reasons already stated. You can have six weeks to get your stuff together and get moved out of here. After that, I’ll pitch it.”

Todd turned around at that.

“Six weeks is plenty of time, Todd,” Janis said.

“Okay,” said Todd.

If Janis was disappointed at Todd’s lack of response, she didn’t register it. Instead she turned and left the room.

“You fucking cow,” Todd whispered to his beer.

* * *

Todd’s response to his wife’s advice was to ignore it. The very next day he went to see Pete Fenton, the man he called his lawyer. Pete wasn’t really Todd’s lawyer, but a few years back he’d advised Todd on a contract Todd had been offered by a vanity publishing company (he’d told Todd it was a piece of crap, but Todd signed it anyway, and then the company went bust), and Todd had been impressed by his frankness and his low rates.

Pete wasn’t pleased to see Todd, who he remembered without fondness, but he’d had an appointment make a late cancellation and it was a shame to waste the slot, so here they were, Pete telling Todd how it was, and Todd not being very happy with how it was.

“She’s got me by the balls,” Todd said.

“Others might see it differently,” said Pete. “Your wife’s character appears to be spotless. The sole difficulty a judge would have with her testimony is staying awake during a description of Janis’s day. Whereas you—”

Pete’s large hands spread.

“You’re a heavy drinker, you have affairs, you contribute nothing to the marriage… it’s a tough one. Even forty years ago, when a husband could do pretty much what he liked, you’d have had trouble fighting this one.”

Todd said, “But it’s a no-fault divorce, right? I don’t mean there is no fault, I admit my failings… I mean, if she’s not going to take me to court, then it’s a fifty-fifty split. Isn’t it?”

Pete almost laughed. “A fifty-fifty split of what? Janis owns the property outright and pretty much everything else. Your half, if you can call it that, is whatever you can get in the back of a van.”

“So you’re saying I don’t have much of a chance?” “I’m saying you have no chance at all, Mr. Milstead. The only way you could fight this is if you had a great deal of money.”

Pete looked at Todd. He knew the answer to his question already but what the hell, he was going to get some enjoyment out of this.

“Do you have a great deal of money, Mr. Milstead?”

Todd’s defeated headshake almost made Pete Fenton feel sorry for him.

* * *