Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

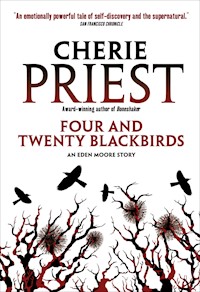

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

When a devastating storm swells the Tennessee River to dam-breaking levels, panic rises. With then gushing waters came a tide of animated corpses: twenty-nine victims of a long-ago slaughter are patrolling the banks, dragging the living down to a muddy grave. No one remembers how they died, and no one knows what they want. Now reluctant medium Eden Moore must dredge up secrets about a long-buried crime that continues to be covered up, before the zombie army can add hundreds more to their ghastly ranks.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 497

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Cherie Priest and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1. Water, Water Everywhere

2. Our Lord and Savior

3. The White Lady

4. After Avery

5. Revitalized

6. The Landing

7. Unwilling Family

8. Vandals are We All

9. Accusations

10. Dead on Market Street

11. Seeing and Knowing

12. The River Walk

13. The Gauntlet

14. Help Me

15. Meet Me

16. The Archives

17. Picture Show at the Paper Plant

18. How should I Put This?

19. Drop by Drop

20. In the End

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

ALSO BY CHERIE PRIEST AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

CHESHIRE RED REPORTS

Bloodshot

Hellbent

EDEN MOORE

Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Wings to the Kingdom

NOT FLESH NOR FEATHERSPrint edition ISBN: 9780857687746E-book edition ISBN: 9780857687890

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: October 20121 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2© 2007, 2012 by Cherie Priest. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this novel are either fictitious or are used fictitiously.

This edition published by arrangement with Tor Books, an imprint of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers.Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

WWW.TITANBOOKS.COM

THIS ONE’S FOR MY HUSBAND, ARIC—BECAUSE THE FLAMING ZOMBIES WERE HIS IDEA

1

WATER, WATER EVERYWHERE

The Tennessee River has swollen again, and nothing stops it. Not the locks or the dams. Not the TVA. I know that it was different once—that Chattanooga was a crossroads, alive and healthy; a place of promise and opportunity. But like all things left wet for too long, it warps. It rots. And now it would drown us all to keep us.

The great gorge fills, and the city sinks behind me.

* * *

In 1973 when the river last rose like this, my aunt Louise was fourteen years old and my mother Leslie was eleven. They lived on the north shore of the city, but this was back before the neighborhoods were renovated into quirky suburbia. There was no sprawling green park or blue-topped carousel with vintage-look horses.

On the very spot where the lion fountains spit water streams in the summer, there once was a closed-up armory. Like all things utilitarian and military, it was gray and smooth with no hint of ornamentation. It was a work building—a barn for the army’s cast-off supplies, surrounded by a chain-link fence.

Lu said she never saw anyone come in or out of the place, and so far as the neighborhood kids knew, it was deserted—and therefore a target. This is a story I had to drag out of her throat, word by word.

She’s never liked to talk about my mother.

* * *

By the time the girls reached the armory, it had stopped raining and the river lapped up against the rocky bank at the bottom of the short hill. The chain-link fence was twisted open in more than one place, and any of those holes was big enough to fit a teenaged girl through.

It was a neighborhood game: who could get inside fastest, who could find the coolest souvenir. Who could stay inside the longest without getting scared.

“It’s empty,” Lu assured her little sister. “There’s nothing in there but a bunch of old equipment, and most of it’s covered up. I don’t know why you’re so keen to get inside.”

“Because you and Shelly went without me last week.” Leslie sulked, peeling the fence back and holding it tight. “That’s why.”

Lu ducked underneath and took Leslie’s hand to bring her through the hole. “If I’d known you’d make such a stink about it, I’d’ve brought you sooner. Now’s not a good time. It could start raining again any minute, and things are flooding up.”

“It’s got to be now, while Momma’s asleep. You were the dummy who got caught. If you hadn’t got caught, we could go on Sunday.”

“We could still go on Sunday if you really want.” Leslie sniffed. “Can not. You’re grounded.”

“Only so long as she knows where I’m at.” Lu pointed up at a broken window. “That’s the best way in. There’s—” She cut herself off. A fat raindrop splashed down onto her cheek. “Jeez. Hurry up. It’s starting again.”

Though the girls looked much alike, Lu was the older, taller, and stronger of the pair. Her hair was knotted into black braids and her jeans were ratty around the knees, showing brown skin and scabs where she’d fallen one time too many. She put her shoulder against a sopping wet crate and shoved it hard. It inched its way to a spot beneath the window. “Hang on, it’s high. I’ll get another one so you can step up.”

“No, I got it.” Leslie hoisted herself onto the crate and poked at the broken bits of glass. She glanced down at her cut-off shorts and wished they reached farther down her legs.

“Don’t touch those. Look. Someone reached inside and unlocked it.” Lu pushed the frame and it scraped against the sill. “Hurry up and get inside. Aw, shit.”

“That’s a quarter for the swears jar.”

“Not unless Momma hears me, it’s not. Get in, and get your look around. We’ve got to be fast.”

“Why?”

“Look at the river.”

Leslie glanced over her shoulder, out to the south and to the bridges. “Wow. I’ve never seen it like that before. It’s right at the edge of the building. Usually it stays down by the rocks.”

“Yeah, it does. This is way too high, and I think it’s getting higher. Look at that boat over there. It used to be tied down at the dock. Look where it is now.”

“Whoa.”

Lu shoved at her sister’s bottom. “Go on. For real.”

“I’m going. What are you, scared?”

“Not of anything inside, no. But I don’t like the look of that water. It shouldn’t be so high.” Even as she spoke, gray waves knocked themselves against the south end of the old armory. They beat a slapdash time there, creeping up along the cinderblock walls.

Leslie’s legs popped over the windowsill and she dropped herself down onto something below. “What’s this?” Her voice echoed loud against the high, corrugated metal ceiling.

“I don’t know. Something to step on. Climb on down, if you’re going to. It’s raining again out here, and I’m getting soaked. And the river… I don’t like the look of it. It’s too full. And…”

“And what?”

Lu murmured the rest. “And I don’t think it’s supposed to be that color.”

“What?”

“It’s always sort of gray and blue. Maybe it’s just the clouds or something.” Lu slung her leg past the broken glass and climbed inside to stand beside Leslie. Together they were perched atop another set of boxes, or possibly a large piece of machinery—it was something covered with a khaki-colored canvas that was thick like a tent.

Leslie stamped her feet. “It feels solid.”

“It is solid. Look at all the footprints on this thing. We do this all the time. Come on down then, if you’re coming. Let’s get this over with. The river’s rising, and Momma won’t sleep forever.”

“Shelly will cover for us.”

“She’ll try.” Lu hopped down to the cement floor and brushed her hands off on her jeans. “But there’s no telling if it’ll work or not. I’m grounded, remember?”

“Forever and a day. Do you think she meant it?” Leslie stepped down beside her, and copied Lu’s hand-wiping gesture. Lu shrugged. “Probably. But that don’t mean she can make it stick. Well, this is it. You happy now?”

“Yeah,” she breathed. “I guess. It’s dark in here. Did you bring a light?”

“No. It’s still daytime. We don’t need a light. Your eyes’ll get used to it. Come on. I’ll walk you through and then we’ll leave and you won’t make a big stink about it anymore. Deal?”

“The whole thing. I want to see everything you got to see with Shelly.”

“Fine, yeah. The whole thing. But we’re going to do it fast.”

By then the rain was not so much falling as plummeting. Louder and louder it came down, and Leslie was right—it was dark inside, despite the afternoon hour. Within the disused armory, all the space was filled with veiled gear and shrouded military tackle. From floor to ceiling the ghostly monsters stood still and silent, lumpy and lame.

“What’s underneath the sheets?” Leslie wanted to know, but Lu didn’t know and nobody else did either.

“Stuff. Army stuff. Big machines and trucks. Boxes of junk. Most of those sheets are tied down, and it’s too hard to pull them up.”

“What? I can’t hear you.”

The rain was too much, the echo was too hearty. Water poured onto the old metal roof as if the river had overturned to empty itself. It drove so steady that the sound fuzzed out to a harsh white noise.

“Hurry up,” Lu said, ignoring Leslie’s request to repeat herself.

“We’re going to have to ride our bikes home in this, aren’t we?”

“It’s only getting worse. This is stupid. Les, this is stupid.”

“Not getting scared, are you?”

Lu looked back up at the window, and down at the floor.

“Les, the water’s coming in. We’ve got to go.”

“Shit,” the younger girl whistled, lifting her sneaker up and splashing it back down.

“Quarter for the swears jar.”

“Not if Momma doesn’t hear it, right?”

They stared back and forth at each other, and held their breath while the sky dropped down outside. “Les. Let’s go. It’s not letting up. It’s just getting worse.”

“Can’t get much worse.”

Lu took Leslie’s wrist and tugged her back towards the window. Leslie’s token resistance was feeble. “We can’t ride in this weather. Maybe if we wait it’ll let up,” she protested, but the water was climbing up her ankles, and the fight was leaving her.

The older girl reached the makeshift exit first and scaled the now-soaked tarp with a couple of well-placed footholds. She used her arm to shield her eyes from the blowing rain that gushed through the broken window.

Leslie prattled on below. “We’re going to have to run for it. We’ll have to walk the bikes and we’re going to get wet in the rain.”

“Jesus, Les,” Lu said. “We’re going to have to swim for it.”

“What? Don’t say that. It’s just rain.”

“No, it’s not just rain.”

“It is rain—I’m standing in it right now!”

“No, Les. It’s the river.”

More water squeezed through the cracks beneath the doors, and the tide crawled up past nervous ankles, past the hems of jeans, up along skinny shins. “Lu? Lu, I don’t like this. Lu?”

“I don’t like it either. Get out of that water. Get up here, now. Come on. You’ll catch cold.” She sent down one hand and Leslie grabbed it, pulling herself up.

“Let me see out the window.”

“No. It’s just water, but it’s coming up fast and I bet we don’t have bikes anymore anyway. They probably washed away by now.”

“You’re just trying to scare me,” Leslie accused, but she didn’t push past Lu to look outside. She reached down to her feet and squished her shoes to let out some of the water. She twisted the bottom of her jeans and wrung out more. “It’s getting cold in here. And the water—where’s it all coming from, Lu?”

“What? Be quiet, I’m trying to think.”

“Lu, look at the floor. Lu, look at the floor.”

“I’m looking! I see it, okay? I see how the water’s coming up.” A loud creak popped through the hideous white noise of the hammering rain.

Leslie jumped and scrambled higher, to stand just below her sister. “What was that?”

“How should I know? Stop it, you’re panicking. Don’t panic. It’s just water. It’s just water.”

“It’s a lot of water.”

“But we’re on top of all this stuff. We’re real high up. It won’t reach us. When it stops raining, it’ll all run back down to the river, that’s what it’ll do. It can’t rain forever. Maybe we’ll even find our bikes. Maybe Momma won’t kill us.”

“You’re going to be grounded until you’re dead.”

“Get on up here.”

Leslie squeaked with alarm, and pointed back at the ground. “It’s still getting higher!”

“Well it’s not going to get as high as the roof or anything. There’s—there’s an attic, Shelly said. She went up there with a boy once, but don’t tell her I told you about it.”

“Which boy?”

“I don’t know. One of ’em. Just, come on. We can climb across these, over to the other side—I think that’s it, that’s the attic door in the ceiling, see it?” They were both getting drenched, standing beside the open window. Lu took Leslie’s face in her hand and directed it to a handle above them, across the armory space.

“I see it. Yeah. We can make that, can’t we?”

“We can make it.” But the water was rising still, filling up the spaces between the cloaked machines. A foot at a time it crawled the walls, so fast that if Lu picked a spot on the wall to stare at, she could count to ten and watch it disappear. At the window the rain was finding easy entry, and the river was waiting its turn.

“This is bad, isn’t it?” Leslie fretted. She stood close to her sister and shivered.

“It’s not that bad. Here. Stretch your legs, you can make that next stack—see? Just crawl and be careful. You won’t fall. You go first. I’ll help you.”

“You go first.”

“All right. We’ll do it that way, then.” Lu reached out one long arm and snagged the tightly fitted tarp on the next pile of junk over. By shifting her weight she closed the distance and grabbed a handful of canvas, using it to haul herself over. She extended her hand back to Leslie. “Here—come on. I’ll pull you.”

Leslie nodded and held out her hand. She let her sister heave her across, and when she arrived on the new spot, she clung to the heap and dug her fingers into its bulk. “Only one more, right?”

“Just one more. Then we’ll be right under the attic, and I’ll pull the door down so we can go up inside. It’ll be drier there. We’ll be safe for a long time. Long enough for the rain to stop and the water to go down, anyhow.”

“Okay. Okay. Don’t let go of my hand.”

“I’ve got to for a second. The next one’s closer, see?” Lu only leaned to reach the second stack of covered military detritus. She could span the gap between them if she stretched her legs apart, so she made herself a bridge and let the smaller girl scramble across her body. “Now give me your hand again.”

She didn’t need to ask twice. Leslie thrust her fingers into Lu’s. “I’m getting scared.”

“That’s okay. This is kind of scary. But don’t freak out on me. Freaking out only makes it worse.” Lu reached for the metal latch above her head and gave it a good yank. The ceiling held, and groaned.

“You’ll have to—Les, put your arms around my waist. Pick your feet up, yeah. Like that. I’m not heavy enough. Pick up your feet. There, that’s it.” Combined, their weight pulled against the springs and coils above, and the hatch reluctantly slumped down with a jerky flop. A ladder on a set of rollers followed it. Lu grabbed the bottom rung and pulled.

“It’s dirty up there.”

“It’s dirty and wet down here. Go on. I’ll hold the door down, you go up the steps.”

“You go first.”

“I can’t. You’re not heavy enough to hold the door down. Just go. I’m right behind you.”

“You better not be fooling me.”

“I’m not fooling you.” Lu’s arms shook as she held the door low enough for Leslie to scale. Beneath them, the water soaked its way up the veiled machines, rising foot by frightening foot. By Lu’s estimation, if they’d stayed on the floor it would have been up to her little sister’s waist; but she also knew that on the other side of the window, more water waited. The whole river was knocking, asking to come inside—and it had shown up quick on the doorstep. She’d sworn the flood wouldn’t make it to the armory’s old roof, but she wasn’t as sure as she pretended.

Later she would learn that a dam somewhere up river had failed, and that’s why the water had come so high, so fast. And later, it was easy to say that if she’d only known, she never would have brought her sister out to explore.

But back then, as the afternoon grew late and the sky went dark and the Tennessee River oozed up out of its bed, Lu could only work with the decisions she’d already made. She pushed at Leslie’s feet, then scurried up after her.

With the weight of the girls removed, the door clapped itself shut into the floor behind them.

“It’s dark up here,” Leslie whispered, because big, dark places made her think of church.

“You said it was dark down there.”

“Well, it’s even darker up here.”

“You’ll get used to it.”

The attic was as dirty as Leslie had declared, and darker than Lu was willing to admit. Rain noise was louder there too, since nothing but the thin metal roof separated the girls from the sky. Lu peeled off her sweater and wrapped it around Leslie, who was wetter and colder, or so it seemed. “Don’t touch the pink stuff in the floor,” she said, pointing to the half-finished floors. “It’ll make you itch, or that’s what Shelly said. It’s insulation. Walk on the boards in between them, if you can.”

“Okay.” On shaky legs Leslie did as she was told, struggling to stand astride the beams that would hold her. “This sucks. We can balance up here above the itchy pink stuff, or balance down there above the water.”

Lu lifted her voice to be heard above the battering rain. “The pink stuff is warm, at least, and it won’t drown you if you sit in it too long. So I’ll take the pink stuff, if it’s all the same to you. Let’s go back there—the floor’s more covered. Less pink stuff to worry about.”

Together they tiptoed across the wood planks and dodged curtains of cobwebs, Leslie going first with Lu’s hands on her shoulders. If either of them had been any taller, they would’ve had to crouch. But as it was, both of them could lift their hands and brace themselves on the underside of the roof.

Leslie coughed and wiped at her face. “It smells gross up here.”

Down by one of Lu’s feet, curled in a pink, fluffy bed, the remains of a rat lay decomposing. “It’s just… old stuff. Old places. They smell like this, after a while. Don’t worry about it. Keep going.”

When they reached the back corner they sat down, curling their arms and legs until they folded around themselves, and around each other. “I’m cold,” Leslie complained, but Lu knew she was mostly just afraid and didn’t want to say so.

“Yeah, it’s chilly in here. But you’ll warm up as you dry off.”

Down came the rain and washed out all the other sounds except for the occasional cracking, creaking complaint of the old armory. But the armory was built to last. It would not fall, it would only fill.

Night settled in early because of the weather, and the rain kept coming.

Antsy and damp, the girls huddled close without speaking much. Once it was dark there was no sense in speaking. There was no reason to talk about heading home; the only real question was when to start shouting for help. The time hadn’t come quite yet—there was a balance that must be tipped. Their fear of their mother had to be outweighed by their fear of being trapped, and for a long time the fear of their mother won out.

Lu also thought that if they stayed missing long enough, there might be a chance that parental relief would be great enough to overrule parental retribution. Her hopes weren’t high, but she was running low on hope as the night dragged on, so she clung to what she could get.

Lulled by the violent downpour and its insistent beat on the metal roof, eventually the sisters dozed.

But they awoke with a jolt and grasped at each other’s arms.

“What was that noise?” Leslie demanded, though she knew her sister didn’t know any better than she did.

The noise sounded again and they were both awake enough to hear it clearly. It was something hard and knocking. Something dense and thick, with deliberate intent.

“Somebody’s there?” Lu guessed. “I don’t know. It sounds like…” She hesitated, listening hard.

There, again. Another blow. This one made their bottoms jump.

Leslie breathed faster. “Somebody’s right underneath us. I think.”

“Not somebody? Maybe something floating.” Lu knew as soon as she said it that she shouldn’t have.

“What? You think the water’s got that high?” There was the panic again. “Floating up so high that it hits against the ceiling underneath us? You don’t really think—”

Lu thought of the river outside the window, and how it boiled at the walls of the armory. She believed yes, that the water could get that high; and she figured that yes, something must be floating up to the ceiling in the hollow space below. But to say so meant that her sister must know it too; and though she was not such a nervous little sister as little sisters went, ten or twelve feet of water underfoot might be enough to send anybody into a fit.

But there wasn’t much point in denying it. The banging continued faster, or maybe only in more places. Maybe it came from more than one—crate? Machine? At least that’s what it sounded like to the girls, who crushed their bodies against each other, trying to be small, and trying to be blind.

Lu said she didn’t really want to know. Leslie didn’t either, and that was why she let Lu cover her eyes with a sleeve, even though there wasn’t anything to see.

There was plenty to hear, from every direction all at once.

“What is that?” Leslie groaned again, her head buried in the crook of her sister’s neck. It did not occur to either of them to call out for help. Whatever was bungling and bumping its way along the ceiling was not friendly, and it was not helpful.

“Shhh—” Lu told her, and she rocked her back and forth.

Pound, pound, pound went the noise until it was louder than the rain had ever gotten, though less rhythmic.

“Oh shit, Lu. You know what they are.”

“Be quiet.”

“They’re hands, aren’t they?

Listen, do you hear them? Listen, Lu. They’re hands. But they ain’t alive anymore.”

“Shush up. Stop talking.”

Leslie lifted her head and narrowed her eyes. “I can hear them. Can’t you? Don’t you hear what they’re trying to say?”

“No, and you can’t either. Hush it, would you?” Lu tried to force her sister’s head back down but Leslie wouldn’t let it go.

“But that door is really heavy, ain’t it? They won’t be able to pull it down, I don’t think. Not unless the water gets higher, and, listen, it’s stopped raining.”

She was right. The sudden quiet threw into sharp relief the dull staccato beneath the floor where they sat.

“Be quiet, Les. For Jesus’ sake, shut up. You want them to hear you?”

“Who cares?” she said, and the eerie, knowing glare she gave to Lu made her stomach knot and sink. “Can’t you tell? They already know we’re here.”

* * *

But the door was heavy, and it held. And by the time the first hint of dawn came creeping down the Tennessee River gorge, the water was retreating its way back to the river’s bed. Though they wouldn’t open the attic door, the girls shouted out to police when they heard the sirens, and when the man with a megaphone called to them from a small, flat boat.

They were home by breakfast, but all of their mother’s worry didn’t keep the pair of them from being grounded indefinitely.

And late at night, while her little sister slept, Lu listened for the hammering of the searching hands. She never heard it again, but Leslie dreamed of it for weeks—whispering frantic prayers into her pillow between twilight and dawn.

Tell the burned-up man it was all a mistake. Tell him it was all a mistake.

2

OUR LORD AND SAVIOR

Christ Adams has a typo on his social security card. I’ve seen it, because he likes to flash it around, in case anyone disbelieves him—and a lot of people do. He’s the most entertaining liar in town.

He slipped another cigarette out of the pack and pushed a lock of Day-Glo orange hair out of his face while he sucked the thing alight. We were sitting together down by the river, on the cement curbs that pass for seating along Ross’s Landing. The pier’s polished metal architecture gleamed in the sharp winter sun, but Christ wouldn’t go near it. He wouldn’t get any closer than the bank, where the terraced steps offered a fine view of the river.

“I’m taking a chance coming this close. We both are. And so are those idiots over there, pushing strollers and fishing. I’d rather scoop my eyes out with a grapefruit spoon than sit so close to the water.”

“It’s a nice day to walk around down there,” I sort of argued. “It’s only a little chilly.”

“It isn’t chilly for January.”

“It’s chilly for me.”

“Whatever, Eden.” He chewed the filter end of his cigarette until it fit the yellowed groove between his teeth. He shook his head and pulled his jacket tighter around his shoulders. Christ was about my height, maybe five foot ten, but I probably outweighed him by twenty or thirty pounds. He had that lean, starved look to him that comes from lots of physical activity and not enough nutrition. His was a body built by nicotine, Waffle House, and artificial sweetener.

“Where’s your skateboard?” I asked, only because I’d never before seen him without it.

He shrugged and twitched, as if the question annoyed him. “Busted. Same night as Pat went missing. I told you that part.”

“No. You haven’t told me anything yet. Since when is Pat missing?”

“Since the same night my board got busted. Besides, if I had it, the cops would’ve thrown me out as soon as we sat down. Some bullshit about defacing the steps. But it’s not our boards that tear up the steps. I don’t care what they say.”

I stretched out and crossed my feet, leaning back and pulling my sunglasses down off the top of my head. “There’s not much arguing about the graffiti, though.”

“That’s just protest. Freedom of speech. If the cops at the landing would leave us alone—”

“Then you’d find some other place to make trouble. Look, man—not today. Just say your piece and let me move along. I’ve made nice. I put down my paper and left my window seat because you had to have a word. Well, have it.”

“All right. You want the fifty-cent version? Here it is: you’d be a goddamn madwoman to move into those apartments over there.” Christ pointed across the river to the north shore, where a low-cut skyline was developing beside the river.

“What the hell? First Lu, now you. What’s wrong with them? They’re beautiful, they’re almost finished, and I’ve already put down my deposit, thank you very much. I’m moving in on the first of next month.”

He cocked his head and took a long drag. “Lu—that’s your aunt? Hell, if I were her I’d be damned happy to have you out of the house at long last.”

“She and Dave have been hinting hard for a couple of years now, nudging me towards getting my own place. But now that I’ve finally taken them up on it, all they do is argue with me about the location.”

“What’s their problem with it?”

“Lu says it’s too close to the river—that when the river floods it’ll be a muddy mess down there. But hell, the whole city clusters up against the river, or at least all the good stuff. You’d have to go all the way back to the ridges to get away from it, and that’s probably a couple of miles. Anyway, that’s what TVA is for, isn’t it? To keep the river where it’s supposed to be? And I’ll get renter’s insurance. I’ll be fine.”

He waved the cigarette at me with one hand and buttoned his jacket shut with the other. “She’s right. It’s too close to the river. I’d be worried about that too, if I were you.”

“Why? What’s so scary about the river?”

With a deep breath and a pensive squint, he answered, “It’s like being afraid of the dark, I think. I mean, you’re not really afraid of the dark—you’re afraid of the things in the dark. That’s what being afraid of the river is like. That’s what I’m trying to say.”

I whacked him with my sunglasses. “So you’re afraid of driftwood and fish, pretty much?”

“The fish in this river? Hell, yeah, they scare me. Haven’t you seen the signs?”

“I’ve seen them.” I nodded. They’re posted at regular intervals along the banks, warning people who fish there not to eat more than one of their catch a week because of the pollution levels.

He dropped his voice and crawled to a crouch in order to bring his face closer to mine. “You know it’s not the fish, Eden. You know it isn’t, as sure as I do. You’ve got to know it too.”

“Jesus, Christ. Settle down.” I pushed him back to a seated position and withdrew, trying to re-establish some personal space. He’s not a scary guy, not really—not for someone thirty years old who still wears anarchy symbols stitched to his clothes. But I’d never seen him quite so agitated. “What’s going on out here that’s got you so wound up?”

“It’s not on the news—not yet—but it will be, soon. The wrong people have been going missing, so no, it’s not on the news yet. But one of these days, one way or another, the right people are going to disappear. And then those fascist media overlords will stand up and take notice.”

“Backtrack for me, please. What are we talking about?”

“People are dying, Eden. Down by the river. Something is taking them, one at a time, here and there. Two skater kids last week. A couple of bums this week. So far, it’s just nobodies like me. But the things in the river are getting bolder, or stronger. They’re coming out earlier and earlier, not just in the middle of the night anymore.”

“All right, I’ll bite—‘they’ who?”

He picked at his shoe, the one held together with duct tape. “Don’t know. If you see them, it’s too late. But they come up out of the water, I know that much. And don’t let the cops tell you that their stupid little community service campaigns are what’s keeping the kids off the landing. That’s bullshit. They’re staying away because their friends are dying.”

“Man, maybe they’re just… leaving. People leave here in droves. Hell, you’ve left more times than I can count. Where was it last time, California?”

“San Francisco. But I came back. These guys won’t be back. And it doesn’t matter. Not yet. Nobody important enough has been taken for the city to stand up and wonder what’s going on.”

His pack of cigarettes slid off his knee and I picked it up, tapping one loose and feeding it to him as if it might calm him down. He lit it off the edge of the one that was nearly smoked down to nothing and gulped down a chest full of tobacco, but it didn’t soothe him any.

“It won’t be me, either,” he grumbled, tweaking his lips around the Camel. “Even if they get me, it won’t be my mangled corpse that raises the alarm. Nobody cares if I go. It’ll have to be someone else.”

“Okay, I think that’s just about all the cryptic I’ve got patience for today, and I’m already full-up on crazy.” I stood and dusted off the seat of my jeans.

He reached out to grab my arm. I thought I ducked fast enough, but he caught my wrist. “Don’t move in there. People are dying, Eden. Not people you’d know, but one of these days a body’s going to float up that no one can zip into a bag and forget.”

“Let go of me, Christ, for real. I don’t know what you’re trying to do here—”

He did as I told him, and put his hands on his head as if it hurt him. “I don’t either. I just wanted to tell you, and see if you got it. I wanted to see if you understood, but I guess you don’t, or you don’t care.”

“Don’t be like that.”

“Fuck you,” he said, but I didn’t hear any real malice in it. He only sounded tired. “Maybe it’ll be you they pull out of the water. Maybe you’ll be the one who makes it an issue. Everybody knows who you are.”

I picked up my bag and the to-go cup of coffee I’d brought from Greyfriar’s. “Don’t remind me.”

“You’re famous. You’re famous,” he chanted in an annoying sing-song. “You’re famous, you bitch. You can wear all the thrift store shirts you can buy, but you’re not like us. Go find somewhere else to hang out if you’re not going to notice.”

I turned away.

It was just Christ. He pulled tantrums like that all the time, like a giant overgrown kid. If he couldn’t get the attention he wanted, then any attention would do. “Switch to decaf, Christ. Come back when you want to talk like a civilized grown-up.”

“Is that all you’ve got? Hey—” He stopped short, like he’d thought of something important. He scrambled up to me and held out his hands. “Hey, okay—try this, then. You know that homeless guy, everyone called him Catfood Dude because he smelled like cat food?”

I thought about it for a second, then nodded. “Hangs around at the food court at the mall, and at the bus stop by the ChooChoo. Always wears that jumpsuit, even in the dead of summer.”

“You won’t be seeing him anymore. He’s gone now, and I don’t mean he hopped a Greyhound for Atlanta. He’s dead. Taken, like the rest of them.”

“I saw him just the other day, in front of the pizza place by Greyfriar’s—on that bench where he always is. I don’t believe for a second that he’s really gone anywhere. Tell me something useful, or let me go. I’ve got things to do today other than hang around and listen to you spinning yarn.”

“He went down by the river, walking last night. One of my boys saw him there, and heard some commotion. Heard some splashing. And this morning? Freddie found that cap that he wears, washed up by the fountains at the bridge. There was blood on it.”

“Oh good grief, there’s no way for you to know that any of that’s true. It washed up? With blood still on it? I don’t buy that for a second.”

“There was hair stuck in it too—and gray shit that looked like fish meat, but was probably brains!”

“And… I think we’re done here.” Next he’d tell me about a still-beating heart found at the bottom of the wading pool at the aquarium fountain next door. I didn’t believe him because I had no reason to. He’d say anything at all if it’d lift your eyebrows.

“Benny’s wrong about you,” he shouted behind me. “You’re not cool. You’re just another self-centered, trust-fund hippie-tart from the mountain!”

I glanced over my shoulder. “Write that one into your next slam poem. It’s not bad.”

He dropped his outdoor voice immediately. “Hey thanks, I will. And if you see Jamie, tell him I’m looking for him.”

“I’ll do that,” I promised.

I climbed up the grassy hill past the stairs and stepped into the street. You can’t get mad at Christ, because that means he wins. You can only beat him by absorbing it all and telling him he’s doing a good job. That’s how deep his insecurity goes—all the way to the bottom. The worst thing you can do to throw him off is to pay him a compliment.

That afternoon was the second time he’d tried to sit me down and tell me something, but there’s only so much rope you can give him before he tries to hang you with it.

I’d learned—partly from experience, and partly from our mutual pal Benny Scott—that it was best to treat him like a kid who refuses to eat. Leave him alone. When he gets hungry enough, he’ll eat. If Christ wasn’t full of it and he really had something to tell me, he’d get around to it eventually, and if I waited him out long enough he’d strip away all the crazy stuff first.

This was just build-up. Foreplay. Or, as I was coming to think of it—time wasting.

True, I hadn’t seen Pat skating around lately and I hadn’t seen Catfood Dude since the day before last, but that wasn’t so unusual. The skater crowd is nomadic and fluid at best, transient at worst. Every now and again someone will vanish for a year or two, and no one will notice until he shows back up again with stories about having moved to New Jersey. Or Boston. Or Atlanta. Or wherever.

In the wake of those who leave, an elaborate mythos might rise up. Stories leak out like fairy tales, as if every place else is some weird, faraway fantasy land. Some of them are kidnapped, some begin flash-in-the-pan music careers, some turn to crime. Some of them go on to have great adventures, a few of which might even be true.

But the point is, they always come back. They all do, whether they want to or not.

3

THE WHITE LADY

I walked towards the coffeehouse but changed my mind halfway there and went back to my car instead. The Death Nugget was parked on the street in front of a fast-food Mexican chain. I climbed inside and checked my cell phone, which I’d left in the glove box.

No surprises there. Harry, my old friend and partner in crime, had called, but I knew what that was about, so I didn’t check the voicemail right away. He’d be in town next week, and if all went according to plan, he’d have my half-brother Malachi with him. This was possibly one of my dumber plans, but now that I had put it into motion I was a little anxious about how it was all going to go down—which was the real reason I didn’t check the voicemail. I didn’t want to deal with it.

It’s been almost three years since I first met Harry, and a bit less than that since I came to know Malachi as someone other than “that guy who tries to kill me every ten years or so.” It would take ages to explain how I’ve come to terms with such bizarreness, but it’s worked itself out to a balance.

The question was, would my beloved aunt and uncle see it that way? Could they get past the fact that he had tried to kill me and get used to the idea that we were trying to be friends?

I doubted it, but in the interest of growing up, moving out, and becoming a proper adult before my twenties were completely behind me, it was time for me to let them know what was going on. I was still working out the finer details of how I was going to break it to them, but that was half the fun of procrastinating and denial.

Unfortunately, this would be an especially tough sell when they were already pissed at me about the apartment. What I really didn’t understand—and couldn’t figure out—was what everyone thought was so wrong with the North Shore Apartments. I’d been inside them, and I could say firsthand that they were fabulous.

They weren’t very big, but that meant they were surprisingly affordable for such prime real estate. And they were gorgeous, with high ceilings, bright white walls, lots of windows and a neat little bar area off the kitchen. Best of all, they were just over the river and down the hill from UTC, where I’d freshly re-enrolled. Come summer, I would begin my quest to finish at least one of my incomplete college degrees.

The apartments were down the street from Coolidge Park, with its lion fountains and its big carousel. They weren’t far from the mountain, and they weren’t in the ghetto. And on a nice day, I could walk to class if I wanted to. What’s not to like?

Of course, none of these selling points had made a dent in Lu’s displeasure. She wouldn’t say why, other than that she thought the location was horrible and that I should move up farther away from the river. Even Dave was surprised by her reaction, so I didn’t feel quite so crazy. He agreed that they seemed ideal, and when he sided with me, it only made Lu more flustered.

I’d ended up leaving the house and heading downtown just to get away from the whole situation. Maybe Dave could talk some sense into her, or at least drag some sense out of her. I couldn’t imagine what had made her so crazy when I mentioned the north shore. You would’ve thought I’d told her I was bringing Malachi over for dinner.

The thought made my head hurt, but it was hard to get away from. The big meeting was only a few days away. I still hadn’t decided whether or not to surprise them outright or warn them beforehand. I was leaning towards an advance warning, for Malachi’s personal safety.

But it didn’t have to be a lot of advance notice, I didn’t think. It could be put for off a little while yet.

My phone began to ring again, and upon checking the display I answered it.

“You coming?” Nick Alders asked, without offering any introductory pleasantries.

“I’ll be there in a few minutes.”

“You’re late already.”

“I got sidetracked,” I said, starting my car and pulling into traffic. “I’m on my way now, so don’t get fussy. This probably won’t work anyway, so I hope you aren’t hanging your entire journalistic career on it.”

The reporter didn’t sound too concerned. “It’s just a filler piece, but it might make a good one.”

“It would’ve been better around Halloween, don’t you think?”

“Yeah, well. The Read House wasn’t having problems back around Halloween. You’ve said it before yourself—the dead don’t give a shit about the calendar or the clock.”

“They certainly don’t seem to,” I agreed. “I wonder what’s got the Lady in White’s panties in a bunch.”

“It would be nice if you could shed some light on the subject. Soon. Because I haven’t got all day. Which is why I said three o’clock, and not three thirty.”

“Knock it off, Nick. I’m practically there already. If you’re really pressed for time, you ought to pick another day to do this. There aren’t any guarantees, and it may take more than a minute.”

“I know, I know. Just get here soon. I’m up on the mezzanine level. Waiting.”

I hung up on him.

He was an impatient bastard, but I tried to keep in mind that he worked with very strict deadlines for a living. He’d moved here from up north—from a Midwestern NBC affiliate to our local Tennessee one. There were rumors that naughty conduct had prompted him to seek professional asylum in Chattanooga, but it was hard to prove and I didn’t really care, so I hadn’t asked.

I first met Nick a year ago, when Old Green Eyes had wandered off from his post at the Chickamauga battlefield. Nick was both a help and a hindrance down there in Georgia, but in the end he worked out to be more useful than useless, so I chatted with him when I saw him around town.

This wasn’t to say we were friends or anything.

I’d agreed to meet him that afternoon because he wanted some unofficial assistance with a story. Mostly I was curious, partly I was bored, and partly I wanted to be distracted from my upcoming family meeting.

Besides, it was the Lady in White. Granted, that’s not the most original name for a ghost, but this one was almost as famous as Old Green Eyes, the quiet, elusive battlefield ghoul.

To tell the truth, I’d very much doubted that she existed at all—at least until recently. Stories about the mysterious lady sounded entirely too made-up. According to local lore, she wandered the second and third floors of the historic hotel, crying piteously and vanishing spookily. There were thousands like her, woven into the history of old buildings across the globe. Often she’s a spurned bride, a widow, or a scorned lover. Usually she’s upset about a man.

I’d long suspected it was a tourist thing, something contrived to lure in curious travelers.

But then I saw it happening, the same thing that always happens when a nervous rumor becomes a real fear: people began leaving. First the housekeeping staff refused to clean a certain room. Then they avoided an entire wing, then an entire floor.

Soon the repair people began refusing to fix the strange damage in that first tainted room. A light fixture here, a curtain rod there. A busted marble-top vanity. A hole in the wall. It didn’t matter if they got fixed, anyway: other acts of vandalism would soon undo the careful repairs.

Before long, the people who were paying to rent the room began leaving, too—in the middle of the night, without pausing to seek a refund. Sometimes without collecting their belongings, or without being fully dressed. They left without looking back.

Though it would seem that at least one traveler had made a phone call to the front desk after taking his leave. He wasn’t a superstitious man, or so he told the concierge. He wasn’t an overly imaginative man either, but there was something awful in that room and he thought they should speak with a priest.

Instead, the hotel management simply quit allowing visitors to stay in room 236.

But the awfulness spread—from the room, to the hall, to the floor.

To the whole building. And then to the media.

To Nick.

I parked down at the end of the block, across the street from the Read House hotel. It’s a ten-story brick affair, built in the 1920s to replace an earlier structure that burned. Part of this one burned too, years ago, but it’s been rebuilt and joined by a parking garage. But I didn’t have any cash on me except for a handful of change, so I fed the meter rather than keep my car close.

Inside, the hotel is made of mirrors and brass, with shiny marble floors for my heels to click against. The ceilings are high and the carpets are patterned with a baroque kind of lushness that wouldn’t look right anyplace at all except in the corridors of a fancy old hotel.

In short, a ghost was all it needed to become a perfect cliché of vintage southern hospitality.

I’d made Nick promise not to bring a camera crew, and I was pleased to see he’d behaved himself. This wasn’t an exposé. It was just an investigation—an attempt to see if I could give him anything to work with. Nick wanted a name, or a motive, or an excuse. He wanted a historical figure to hang this ghost story on, so he’d have something to take to the network in a tidy, three-minute package.

I met him up on the mezzanine, where he was lounging on one of the big pseudo-Victorian couches. A bright chandelier loomed above him, bathing the area in sparkling brightness.

He grinned at me and rose, opening his arms in a gesture that encompassed the entire floor. “What do you think? Spooky, or what?”

I smiled back at him, because I didn’t really have a choice. His TV face is contagious when he turns it on and lights it up. “Or what, at the moment. It’s tough to get a good chill going before suppertime.”

“That’s no way to get into the spirit of things,” he cheerily fussed. With one hand he lifted a satchel off the couch and slung it over his shoulder. I was happy to see that he wasn’t in “about to go live” mode. His hair wasn’t sprayed into immobility, he hadn’t bothered with a suit, and, to my astonishment, the man was wearing jeans. I would’ve sworn he didn’t own any.

“I have to say, I think this is a good look for you. Less…” I looked for a word, and found it. “Smarmy.”

“You think? Damn. I should’ve worn a suit. I didn’t mean to put you at ease or anything.”

“Then consider your day a failure and brief me already. What’s the story? Or, should I say, what’s the scoop?”

“There’s no scoop, yet—not past what you already know. Weird shit keeps happening, and the hotel’s new owners are freaking out. The long and short of it is that room 236 would prefer to remain unoccupied.” He pulled a digital voice recorder out of his pocket and held it out to me. “We need one of these, right? Isn’t this what you used when you worked with Dana Marshall?”

I shrugged. “Can’t hurt. Might help. Probably won’t be necessary. And what do you mean ‘new owners’? I thought this place was family-owned or something.”

He cocked an elbow towards a bit of repair scaffolding at the end of the hall. A major chain logo was emblazoned on the side. “It’s been bought out. Back in November. That’s why all this renovating is underway—they’re going to revamp the place and set up a storefront down on the first floor. They’ve already gotten the Starbucks open and ready for business.”

“I know, it’s revolting. And right down the street from Greyfriar’s, too.”

“Hey, I like Starbucks.”

“Philistine.” I glanced around and noticed, for the first time, that there were corners marked off with construction signs, and an elevator door with an “Out of Service” notice across it. “I don’t know. Maybe the old place needs a facelift. Maybe the previous owners couldn’t afford it.”

“Maybe. But I bet you a five-dollar espresso beverage that that’s not the reason they sold the place.”

“You’re thinking they couldn’t handle the ghost.”

“Precisely. Half their night staff has walked out and the other half demanded hearty raises for hazard pay. According to the day manager, the big chains had been circling like sharks for a while anyway, making offers, courting the family—hoping to pick the place up. It’s on the historic registry now, and with a little spit and polish, the big boys could turn this into a five-star affair.”

I guessed the rest. “And when the owners changed their minds about keeping it in the family, it didn’t take any time at all to find a corporate sucker with deep pockets to take it off their hands. Have you talked to the old owners?”

“I tried. They weren’t feeling very forthcoming.”

“That figures.” We stood there for a minute, looking and listening around. Seeing and hearing nothing. “This is just a fact-finding mission, right?” I asked, noting the room number nearest me and assuming we must be close to the troublesome quarters.

“Sure,” he agreed, tapping his fingers at the recorder I was still holding. “But wouldn’t it be nice if we found some spooky facts and got them on tape? Wouldn’t that make for a marvelous addition to the story?”

“You don’t really think they’d let you run it, do you? They’d get letters, I’m sure. We can’t have our local affiliates promoting the occult, inviting the presence of Satan and all that jazz.”

“You can’t be serious.”

I smiled while I fiddled with the recorder. “Oh yeah, that’s right. You’re not from around here, are you?”

“No, thank God. But Chattanooga residential temperament is neither here nor there. If this turns out well enough, I can always take a stab at going to the network. I’ll just label it a human interest piece and see who bites.”

“Or ‘post-human interest,’ as the case may be.” The recorder he’d handed me was an expensive model with plastic wrap still clinging to it. I picked off the leftover packaging and flipped it on. “Just so you know, this might not get you anywhere. It might not turn up anything at all. Even if the room is haunted, ghosts don’t always feel very talkative.”

“Why else would they act up, though, if they didn’t want to communicate?”

“Any number of reasons. From what you’ve given me so far, I think maybe this one wants to be left alone. Maybe the remodeling is making her crazy. The dead are like cats, in my experience. They don’t like change. You start messing with their familiar surroundings and they get antsy.”

“But this one started acting up before the buyout and the construction.”

“Maybe I’m wrong then. I don’t know.”

He pointed down one of the wide corridors and jutted his chin towards a door. “That’s it. Room 236. Go take a stab at finding out. Uh—is there anything I need to do? Should I come with you? Stay out here?”

“Stay out here. I probably won’t be long. If there’s something in there and it wants to talk, great. If not, you’re out of luck.”

“Try to get me a name, or something I can check out on the Internet, or through genealogy records. Maybe we’ll turn up a grisly murder.”

“Yeah, wouldn’t that be great?” I said, but he didn’t seem to get that I was joking.

“Hell yes it would. If she bleeds, she leads. Even if she bled out a hundred years ago. People eat this stuff up.”

“Your selfless pursuit of justice does you credit.”

“They’re going to give me a Nobel any day now, I can feel it. But I’d settle for a Pulitzer.”

“I bet you would.” I checked that the digital recorder was on, and then I took the card key.

“Feel free to chat into the mic yourself. Share your impressions of the room, the things you see. The stuff you hear. By all means sound a little panicky if you want. People dig panic.”

I slipped the card key into the slot lock and a green light appeared, letting me know that it was open. “Sure. And while I’m at it, I’ll slip into something flimsy and investigate a strange sound in the basement. Would that work for you?”

“Like a charm.”

“Stay put,” I told him. “I’ll be back out in a few minutes. Keep quiet, and don’t knock or anything.”

“What if you need help?”

“I don’t see that happening. Shut up and wait.”

I slipped inside and let the door slide close behind me with a hydraulic click. Within the room it was fairly dark, but afternoon sun oozed around the edges of the thick tapestry curtains.

I went to the window and found the long white rod and pulled it to the right, drawing the curtains and their thick shade liner aside.

Thick puffs of dust accompanied the swishing of the curtains, and when the daylight poured in I saw that yes, it had been a while since the place was cleaned. With two fingers I swiped a shiny trail in the finish of the nightstand.

The bed was covered with a floral print spread, laid out in shades of green, maroon, and cream. A sturdy, cherry-stained headboard was fastened to the wall, and a large armoire held a television. I didn’t see a remote control. There was a coffeemaker, though, and an empty ice bucket beside the vanity sink.

“Hello?” I asked the room. “Anybody here?”

I don’t go in for too much formality, because in my experience it doesn’t help much. More often than not, the trigger is something simpler—something obscure and important that you’d never think about in a million years, anyway. You may as well wing it.

I tried a mental rundown of all the things a maid might disturb.

I pictured a big cart, laden with towels and shampoo samples. I imagined a vacuum. Dust rags. When would it begin? What would rouse the Lady in White?

“Anybody?” The red light on the recorder shined an electric thumbs-up that said all was well and ready. “Can anyone hear me? Would anyone like to come out and talk? Or is the staff here completely bananas?”

I muttered that last part.

A tiny electric shock zapped my hand, and I dropped the recorder. I shook my hand to chase the prickling sensation away, and bent over to retrieve Nick’s little toy.

Then the television sparked too, over on my left. It gave a half-hearted spit of electricity, sending a bright line across the center of the screen. Then the screen went dark again, except for the square reflection of the big open window.

I saw a pattern there, on the screen. It was illuminated by the slanting sun.

I left the recorder where I’d dropped it and approached the TV. I knelt before it and angled my head to best see the dusty residue in full relief.

“Now we’re talking,” I breathed. “You are here, aren’t you? You can come out if you want. I’m not afraid of you. I’ll listen if you’ve got something you’d like to say. I’m good at passing messages around.”

Pressed into the dust on the screen was a flattened imprint. “Is this you?” I asked, sneaking my fingertip up along the gray glass. “Is this your face? Did you put this here?”

Very clearly I saw it, and the closer I looked the more details became apparent. A cheek was pushed into the set, with an open mouth, and a closed eye. Along the edges of the eye I spied faint feathering, where lashes had brushed themselves against the dirty monitor.

The face was hard to read, since I could see only the half impression. It might have been angry, or sad. Or frightened.

A quick tickle of movement caught my eye. Something flickered through the window’s reflection, but it moved too fast to watch, to register what it was. It might have been an arm, or a sleeve. Something that waves, or directs, or hits.

But when I looked away from the screen there was nothing there in the gold patch of light beside the bed.

No matter how hard I squinted I couldn’t make anything out of it, not any proper shape or message. Only… if I used my imagination, I might have said that there was a place in the beam where the dust didn’t swirl or float. There may have been a blank spot, where the air was clear. If I thought about it. If I was looking for something to see.