Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

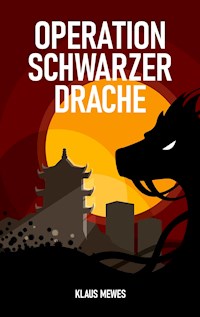

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

COVID-19. For months, the coronavirus has been holding the world in a death grip. By now, it's dawning on people that nothing will ever be the same. It's the liberal societies of the West that are feeling the merciless impact the most. Besides the immense, spiraling costs, they must also cope with the reality that their freedom-orientated societal models are beginning to unravel because of this disaster. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the West is faltering. The West as a colossus with feet of clay- that’s what’s impelling the men around Chinese intelligence agent Yue Fei. Author Klaus Mewes has written a gripping thriller, a sophisticated mixture weaving together geostrategy, the history of the virus pandemic, and the research behind it. Klaus also expertly uses China’s breathtaking development and eventful history over the past thirty years to infuse his story with realism. The author sheds light on the - fictitious, to be sure - events leading up to the outbreak of the pandemic. Meanwhile, a young woman physician, Shenmi, lives through the 1989 events that occurred on Tiananmen Square. Traumatized, she withdraws emotionally. That is, until the death of a boy during the 1997 H5N1 flu epidemic changes her life yet again, and she resolves to dedicate herself to researching viruses - specifically, coronaviruses. Yue Fei, however, the cunning intelligence agent, is playing his own game. Failing in his hunt for dissidents and professionally exiled as a consequence, he contemplates revenge and the opportunity to rehabilitate himself in the eyes of his superiors. One day, by random chance, he stumbles across an old acquaintance - whereupon he hatches a plan that will change the world. Now begins a breathless race against time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 510

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To reach the river’s font, one must swim against the current.

Confucius

Contents

Forcing the Relations to Dance I

Incident

On the Golden River

White Lotus

Charade at the Fragrant Harbor

Snail Mail

Purple-Red Death

African Nights

Forcing the Relations to Dance II

Lucy the Icebreaker

Retribution

Good Luck Charm

On the Scent

Sparks Flying at the Powder Keg

The Egg of the Black Dragon

Forcing the Relations to Dance III

Now or Never

Epilogue

Forcing the Relations to Dance I

The black luxury car, a Hongqi L9, drove slowly past the saluting guards. The man sitting in the rear seat didn’t return the salutes. His expressionless eyes seemed to be directed at something indeterminate in the distance.

The first two characters on the license plate indicated that the vehicle belonged to the CMC, the Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China. The subsequent digits, 02019, stood for the glittering future that would soon be dawning. Very soon.

The driver drew up to a stop in front of the main gate of the massive building on Fuxing Street, which resembled an oversized Chinese temple. A soldier opened the car door and stood stiffly at attention as the passenger, a dignified man perhaps in his mid- or late sixties, stepped out. He was wearing an elegant Brioni suit, Navy Cuts by John Lobb, and eyeglasses with narrow, delicate frames—all in all, a gentleman with a distinctly intellectual bearing. As the man vanished into the gray building with a buoyant step, his driver struggled to keep up. After all, the large pilot’s suitcase he was lugging was quite heavy.

In the long corridors, neither the man nor his driver even glanced at the saluting soldiers in acknowledgement. Nobody dared detain the two men, and they soon reached the lower level in the central part of the building, despite its numerous x-ray scanners, for everyone in this building knew the man. It wasn’t necessary—and for that matter, it probably wouldn’t be exactly auspicious for a soldier’s career—to demand their papers in the manner actually required by the strict regulations.

Using a heavily guarded elevator, both men finally reached the hermetically sealed sector of the building. A retina scanner released a door and admitted them into the room, which had been fortified against a potential nuclear attack. Secured against bugging and wiretapping, this room was the command center of the People’s Liberation Army’s headquarters, an underground maze of corridors that linked hundreds of rooms with one another.

Finally, the man opened the door to one of these rooms and entered. All talking immediately died down; the men who had gathered in this room rose to their feet and bowed their heads in silence.

They stood there for a brief time until the man finally spoke to them: “Comrades. You all know me.”

“Of course we know you, Vice President Wang,” resounded their voices to him in an echo, as though coming from a single mouth.

Of course they knew him—Wang was the Vice President of the Zhong Chan Er Bu, the military secret service arm of the People’s Liberation Army. In this capacity, he had direct access to the Party’s innermost circle of power, the Politburo, whose eyes and ears he was—and thus one of the Middle Kingdom’s most powerful movers and shakers.

The rest of those present, who numbered perhaps twenty-five, were the heads of the department for covert operations. A sworn group comprised of the most experienced men in government service, men whose capabilities didn’t lag one bit behind those of their CIA counterparts.

Sitting a bit apart from this group was an athletically built man in his early fifties, who seemed a bit like a foreign body—he appeared to be a civilian. In any event, he wasn’t wearing a uniform, and nothing about his bearing conformed to the usual standard prevailing in this building. To the others, he came across just a soupçon too nonchalant, almost a bit undisciplined. The way the man was chewing on a pencil, with his elbows resting on the table and his eyes half-closed, made him seem more like a detached onlooker rather than someone sitting directly opposite one of China’s most powerful shadow men.

While the others waited, expecting that Wang might reprimand the stranger, Wang himself merely continued talking. “Naturally, you’re all asking yourselves why I’ve ordered you to this meeting, and you have a right to know. However, it’s a bit complicated, so I’ve got to tell a somewhat lengthy story in order to explicate the reason for today’s gathering. I assume that each of you is familiar with the legend of Heilong, the Black Dragon.”

The men in the room looked at each other inquiringly; obviously, they knew the legend of the Black Dragon. In the Middle Kingdom—in contrast to, say, Europe—dragons generally carried positive associations. In China, since time immemorial, dragons hadn’t been demonic, murderous beings but rather deities that even today were still worshipped in many of China’s rural areas. People expected dragons to ensure good harvests, plentiful rain, and good health, or simply protection from all manner of evils.

For thousands of years, powerful Long Wang, dragon kings like Ao Guang, had been spoken of with great reverence, lest one incur their displeasure. Ever since, dragons and humans lived in harmonious equilibrium; humanity paid the dragons tribute in the form of reverent respect, and in exchange, the dragons vouchsafed humans aid and protection. There were also evil dragons, of course, the most dreaded of which was Heilong, the Black Dragon.

“The Black Dragon has been wreaking havoc since the dawn of time. In the Ancient Kingdom, the people believed that, more than anything else, it was he who bore responsibility for floods, storms, and other natural disasters. That’s why no dragon was dreaded more than he—the destroyer of everything built by the hand of man. On the other hand, the legend also holds that the mother of Confucius, our most honored Master, gave of herself to the Black Dragon in human form and then gave birth to Confucius himself, one of our greatest thinkers. Accordingly, Confucius would then be the son of the Black Dragon, from which it would follow that the Heilong, too, has not only a cruel side, but also a very wise one.”

Wang paused and looked around the room. The men looked him expectantly—where could the vice president be going with this?

“Are any of you familiar with the theory of the Black Swan?” Wang now demanded to know.

The men glanced at each other, uncomprehending. What the hell was the vice president trying to tell them with these animal stories?!

“No?” He continued, unperturbed. “Then let me help you along a little; in ancient Rome, there was a satirist named Juvenal. In one of his writings that has come down to us, he holds forth about the loyalty of wives as follows: A loyal wife, according to Juvenal, is a rara avis—a rare bird, nigroque simillima cygno, resembling a black swan. Now all of you must realize that at that time in Europe, unlike here, swans were unknown, so the import of this sentence is rather unflattering to wives.”

Stifled laughter followed his comments.

“It involves a ‘Black Swan,’” Wang went on, “meaning that it’s a metaphor describing something that actually ought not exist. Something which, though indeed extremely improbable, is nevertheless possible theoretically. This metaphor was first used in 2001, the Year of the Snake, by a Lebanese stock-exchange trader and financial mathematician named Taleb. He was describing events which, put simply, arise suddenly, and above all, unpredictably, changing the course of things.

“To sum up: We’ve got two mythical creatures, a dragon and a swan. Both are black; both stand for mighty events that change the course of things. While the swan has the sole quality of unpredictability, the dragon is at once both cruel and wise. And—this is decisive—while the swan stands only for the event as such, it is the dragon that unleashes it. The dragon brings about the event, and the swan is the result of the dragon’s actions. So, the degree of the Black Swan’s power depends upon the Black Dragon’s will and power. Are you all following me?”

He looked into the men’s clueless faces. No, they couldn’t follow his train of thought. It wasn’t clear to any of them, even in the most rudimentary way, where the vice president was going with all this—except to the man in the back, who was now stretching comfortably. Wang smiled enigmatically.

“I’ll return to that later. By then, I’m sure you’ll understand. For now, let’s come to another topic. Our future.”

The men relaxed. This was something they had heard a hundred times already—the future, the Great Resurrection of the Chinese Nation, which had commenced long ago, under the Great Chairman Mao Zedong, and would now be brought to fruition by President Xi. In numerous speeches over recent years, the country’s leading politicians had sworn fealty to this goal, and the Eminent Leader Xi himself had laid down a timetable for it. The first phase, running through 2020, was almost complete. During this period, the country was supposed to increase its industrial manufacturing capacities and, particularly in the realm of digitalization, catch up with the West. In the second phase, lasting through 2025, the overall quality of every manufacturing sector was supposed to be fully developed, with energy consumption and pollutant emissions reaching the levels of the developed economies.

The longer-term objective was for China to be positioned among the middle-ranking industrial powers by 2035, and by 2049—the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic—the Middle Kingdom was supposed to be the world’s top industrial nation. These goals represented the Party cadres’ ambitious timetable for displacing the United States as the world’s leading industrial nation.

Wang, however, to his listeners’ surprise, continued with something unexpected: “Our future, dear Comrades, began five thousand years ago. In the West, this era is called the Bronze Age. While people in the regions that have been setting the pace for the world were only beginning to build civilizations in this epoch—and while at best the Sphinx and the pyramids at Giza attest to an advanced civilization there, the Yellow Kaiser, Huangdi, was founding our advanced civilization. In our kingdom, advanced civilization was already coming into existence under him and under the other four ancient emperors who succeeded him. They had calendars, schools, a written language, musical compositions, and astronomy. Besides that, Kaiser Yao invented the game ‘Go’ that we all know and love.” Wang smiled briefly.

“Generally, we consider this epoch to be the Golden Era. Although everything there merges together, things could not remain static, even then. Consequently, the empire was struck by several disastrous floods on a gigantic scale. Hundreds of thousands lost their lives, and the few remaining survivors hardly possessed anything more than the clothes on their backs. People believed that Heilong, the Black Dragon, bore responsibility for this.

“The hero, Yu the Great, confronted him and managed to tame the floods by building dams, the remains of which we can admire even today. In gratitude, the last of the ancient emperors, Shun, appointed Yu to be his successor. Yu was the founder of our first dynasty, the Xia Dynasty, which today is considered the cradle of ancient China.” The men in the room listened, enthralled—where was the vice president going with all this?

“Under Yu, the Golden Era continued, but after his death, Heilong avenged himself against the people. Yu’s descendants fought vicious battles to determine who would succeed him, and eventually the empire disintegrated. Jie, the last Xia Emperor, was so vicious that the people eventually overthrew him—even today, we regard his name as synonymous with cruelty and viciousness.”

Wang paused momentarily, dabbing a few beads of sweat from his forehead with a small silk kerchief. “Now, why did the First Empire disintegrate even though it was hundreds of years ahead of the rest of the world in many areas? Because of poor leadership and divided leaders.

“Such, Comrades, is the First Teaching that the Great Chairman, and all who have succeeded him, down to our Eminent Leader Xi in the present day, have concluded from our history: Absolute unity is the indispensable prerequisite—not only for China to take its rightful place in the world, but also to maintain its ground for all time.”

He glanced around the room. “I presume that you were expecting something besides a history lesson. Well, you won’t be disappointed, but as I’ve already said, I need to go on a bit longer …

“Nor were the three dynasties that followed in the early period of the kingdom granted a lasting existence. The cause? Besides internal strife, other nations were also constantly mounting attacks that ravaged larger and larger parts of the kingdom. Today, you can still see one fruitless attempt to prevent that: the Great Wall.

“Twenty-two hundred years ago, out of the ruins of the Qin Dynasty, there emerged the Han Dynasty. During its four-hundred-year rule, the Middle Kingdom rose, for the first time, to become a global trading partner. Both culture and economy flourished again, and even trade was conducted with the other great world power of that time—ancient Rome. But due to division among the princes, even the great Han Dynasty disintegrated, ushering in the interregnum of the Three Empires and a further period of internal strife. More decay and weakness followed. Empires formed and battled one another, ruling houses came and went, and China always foundered, mostly by its own hand, due to its disunity.

“Eventually, the Tang Dynasty emerged about fourteen hundred years ago, and with it, our forefathers were granted another three hundred years of prosperity. And yet again, it became manifest that the Middle Kingdom—once united and pacified—was culturally and economically superior to every other empire extant in the world at that time. One illustrative example: even then, we were capable of manufacturing steel—whereas the Europeans ‘invented’ this process just a hundred and fifty years ago.

“Of course, you all know that this empire, too, perished due to our forefathers’ disunity. What followed were several attempts, more or less successful, to unite the sub-empires that grew out of it, until everything collapsed under the incessant Mongol onslaught; had the empire been united and strong, perhaps it could have withstood the Mongolian attack.

“The foreigners’ attempt to obtain a lasting dominion over our territory in the form of the Yuan Dynasty miscarried, not least due to the resistance of the Red Turbans. After the Mongols were largely driven out, the Ming emperor established a new Chinese dynasty that determined China’s fate for roughly the next three hundred years. Now, if you examine the period extending from the time of the Three Emperors, all the way down to the end of the Ming Dynasty—around a thousand years—it becomes clear that our ancestors, despite their internal fragmentation, were vastly superior to all other peoples of the world. It was during this period that we invented paper, porcelain, gunpowder, and the printing press. In the fields of mathematics, astronomy, physics, and chemistry—why, even meteorology, we were vastly superior to everybody else. And finally, nobody could hold a candle to us in agriculture, which, of course, was vitally important at the time.

“The Ming epoch also witnessed the dawn of China as a first-class seafaring nation. You’re all familiar with the accomplishments of Grand Admiral Zheng He, whom we revere, with good reason, as the father of our navy—which is still the world’s second largest. One wonders what we could have achieved if only we had been united! But the time was not yet ripe, so we had to keep waiting to take our rightful place in the world.

“The Ming emperors, however, grew intoxicated by their power and ever more disconnected from the real world, and they neglected to take care of the people. The peasants went hungry, leading to the revolt that swept away the last Ming emperor, Chongzhen. Another reason for the revolt’s success was that the traitor, Wu Sangui, opened the Great Wall to let in the Manchu’s foreign armies, thus furnishing them the opportunity to overrun the already strife-torn empire.

“Such, Comrades, is the Second Teaching that the Great Chairman, and all who have succeeded him, down to our Eminent Leader Xi in the present day, have concluded from our history: Control the power of the people. The amassed power of the people, Comrades, can sweep aside any ruler at any time. That’s why the people’s power must be confined—channeled, controlled, manipulated, and, as the case may be, limited—in a timely manner.”

Wang briefly paused again and drank a sip of tea. In the meantime, his listeners had switched from a state of cluelessness to one of encroaching despair upon being reminded that regardless of how many times China had ascended to greatness, it inevitably fell again. Every man among them knew the Great Nation’s history, which had been drilled into them through hundreds of classroom hours at school and at both the military and Party academies. What, then, was compelling Wang to recount something they already knew?

After all, the order to attend this meeting had required the highest level of secrecy—yet what they were hearing was hardly a secret. Then again, all of them also knew about Wang’s legendary reputation as a master of the shadows. The man was reputed to possess razor-sharp intelligence, blindingly fast perceptive faculties, and brilliant analytical powers. He excelled at making decisions and had no scruples about using every means at his disposal that served his objectives. He was also so loyal to the Party leadership that the cadres relied upon him blindly. To put it another way: Vice President Wang was ideally suited to head the intelligence service, and to the men in the room, certainly, it would have been utterly inadvisable to betray any signs of encroaching fatigue.

“Comrades,” Wang began again. “Have just a bit more patience with me; I see you’re all growing a bit disheartened.” The menacing undertone caused his listeners to stiffen their stance, and they immediately drew themselves to attention. Wang smiled grimly. “So, where was I? Oh yes—the Manchu. As you know, they established the last imperial dynasty of the Qing, which is generally deemed one of the most successful, also because it brought forth, in part, breathtaking cultural and economic achievements. Under the Ming, our country attained its greatest extent in terms of surface area, and due to the favorable conditions, the peoples within its borders multiplied so rapidly that even two hundred years ago, the empire’s population constituted 36% of all humans living on the planet. At that time, the empire was generating around 33% of the entire world’s economic output—about as much as in all Europe at that time. You can imagine, Comrades, that such a wealthy country will engender envy.

“While China, conditioned by its self-fixation, which had proved its worth over thousands of years, paid no attention to the rest of the world except for peaceful trade, other countries, especially those in Europe, were beginning to conquer the world by sword and fire. They were no longer satisfied merely with peaceful trade. Instead, they began to divvy up both the old world and the new, seizing possession of both. And naturally, China, due to both its wealth and its weakness, was an ideal prize.

“It sounds paradoxical, but once again, China’s economic strength was what precipitated its downfall. The Europeans—above all, their most powerful country at the time, Great Britain—wanted more and more Chinese goods, so imports of Chinese products like tea, porcelain, and silk, rose sharply. Conversely, however, China imported hardly anything at all from Europe. That discrepancy led to a ballooning trade deficit on the English side, to which Britain no longer wanted to acquiesce. After the Emperor refused Britain’s inferior textiles, the British hit upon the idea of selling the Chinese the opium that was increasingly being cultivated in Benghal.

“In China, opium had been popular for centuries, albeit forbidden, which the British well knew. Since Britain didn’t want to openly oppose the prohibition, a move that would jeopardize their legal trade with China, they had Chinese smugglers do their dirty work. In a very short time, they managed to smuggle so much British opium into the country that China was positively flooded with the stuff. That had three grave consequences: First off, almost half the Chinese population become addicted and apathetic. Then, in an astonishingly brief span of time, public morals degenerated, and large portions of the population became destitute. And finally, the Chinese currency collapsed because the financial system could not cope with the outflow of the large quantities of silver necessary to pay for the narcotics. In this way, the people rapidly became more and more impoverished.

“So now, when the Emperor responded and attempted to use force to halt the unchecked activities of the British in his country, the so-called Opium Wars resulted, the ignominious course of which I would rather not recite at this juncture. However, it ought to be etched in the brain of every Chinese person that what followed was the consequence arising from China’s weakness vis-à-vis the impudence of foreign powers.

“Such, Comrades, is the Third Teaching that the Great Chairman, and all who have succeeded him, down to our Eminent Leader Xi in the present day, have concluded from history: Under no circumstances may foreign powers ever again acquire influence in China. Never!

“The consequences of the so-called Opium Wars were devastating, and even today, they cause the face of every Chinese to redden with anger. The empire was compelled by military force to continue importing enormous quantities of opium, leading to a runaway pauperization of our people. Having lost the wars, the Chinese had to enter into commensurate ‘treaties’ with the victors. Treaties in which these victorious powers secured themselves permanent prerogatives in strategically significant military bases on Chinese territory. Europeans continued to attempt meddling in Chinese political affairs for their own advantage—much to China’s detriment. Here, I’ll cite Xianggang—called ‘Hong Kong’ by the British extortionists—and then you’ll immediately realize what an arduous, humiliating process it has been for us to reclaim our rights as we have revoked these so-called treaties, step by step.

“Due to the impoverishment of the people and the increasing hopelessness and corruption in the administration of public affairs—above all, the rampant corruption—the final upshot came in the form of the bloodiest civil war in all of human history, the Taiping Rebellion. It cost twenty to thirty million people their lives. This civil war, which ushered in the ongoing death throes of China all the way until 1949, was, if nothing else, also exploited by foreign powers to further weaken China and to divide the country and its economy among themselves. The saddest chapter of this story is not merely that many of our ancestors emigrated when they saw no future for themselves in their own country, but that they were also often sold as coolies and demeaned.

“Yet this harrowing chapter also had its positive side; today, about fifty to sixty million Chinese live abroad and can be found in almost every country around the world. Many are the descendants of these one-time coolies. Through our diplomatic representatives, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the entire work of the United Front, we remain in close contact with these people—and we’re using these contacts to convey our message to the world in a sustained manner.

“But patience, Comrades, as we still haven’t reached the topic for which you’ve all been assembled here. During the so-called Opium Wars, the government kept losing more and more spheres of authority to the foreign powers. So, it was forced to cede customs inspections and authority over trade. Because this caused the government to lose revenue, it had to take out loans from foreign banks, deepening its dependency upon foreign powers.

“As a result, the once-proud Middle Kingdom descended to little better than the status of a European and Japanese colony. The Japanese, meanwhile, just like the Russians, also wanted to grab a slice of the pie for themselves. In the first Sino-Japanese war, just over a hundred and twenty years ago, our fleet was ultimately destroyed, and Japan began to annex territories of the empire.

“Eventually, the aggressors partitioned the empire among themselves into various spheres of influence, where they even proceeded to station troops. Our demise had thus reached such a magnitude that opposing forces among the people finally began stirring. An early uprising against the invaders was led by the ‘Movement of Associations for Justice and Harmony’—known in the West as the ‘Boxer Rebellion.’

“True, this uprising was viciously crushed by the long-nosed devils, but as a result, the flames of revolution were kindled in the people. And their rage was increasingly directed at the decadent rulers of the Qing Dynasty, which had acquiesced to the foreigners’ machinations.

“From our Great Chairman, it has come down to us that as a young man he cut off his traditional queue, as an outward symbol of his rejection of the imperial house. That was the period in which the Qing Dynasty met its inglorious end, ushering in the time of the Great Chaos, when various Chinese warlords—particularly those warring with Japan at first, but later against one another—battled for dominion over the Middle Kingdom.

“Even the conclusion of the First World War didn’t end this inglorious state of affairs, but rather strengthened the position of the Japanese, who ever more brutally attempted to turn China into their own colony. Eventually, they proclaimed the puppet state Manchukuo and actually installed Puyi, the last of the Qing emperors, as the nominal governor.

“Indeed, by declaring war on the Central Powers in World War I, China had sought to benefit from the goodwill of the Entente, in order to secure their protection against Japan. But the one hundred and forty thousand Chinese dispatched to the European theater of war had been sent in vain; after the war, the ungrateful victors gave the Japanese a free hand.

“So once more, China found itself in a state of internal strife and beset by outside powers that were exploiting this condition. Yet as the German philosopher Friedrich Hölderlin once remarked: ‘But where danger lies, the saving power waxes too.’ Almost a hundred years ago, three years after the end of the First World War—right in the middle of the seemingly endless frenzy of the descent—the Communist Party was founded in Shanghai. Then it took yet another twenty-eight years before our Party was able to bring almost all of mainland China under its control. Twenty-eight years of utter war and chaos had turned what had once been the world’s wealthiest, most powerful country into a poorhouse.

“In 1949, the rise of China to the Middle Kingdom began anew; an empire that was to stand head and shoulders above all others. Because that is our rightful place.”

Once again, Wang briefly paused, but only to cast a determined glance into the faces of his listeners. As he continued speaking, the men noticed how his intonation and facial expression changed. The businesslike gentleman’s features were now taking on something fanatical, even imploring. Speaking here was someone who was steeped, at the most fundamental level of his being, in the sense of being on a mission; someone for whom any and every means to attain his goal was justified.

“And now, seventy years later, we stand in the shoes of our forefathers. In these past seventy years, we have traveled far on the path back to the zenith, but as before, there are obstacles before us, and it now behooves us to clear the path before us. We have come into a thousand-year-old inheritance, a great promise, a mission. And we have been ordained by history to be the decisive generation that fulfills this mission. And for this mission, it is we, in this room, who shall be poised at the tip of the spear.”

With these words, Wang left the podium and sat down among the others. A hush fell over the room.

Incident

People stood on the street, jammed uncomfortably close together. All day long, the throngs, the smog, and the heat had exacted their tribute in the form of fainting cases. Yet the mood was good, even exuberant. For weeks, the masses of people on the streets had been feverishly awaiting this day. More than ever, the city resembled an anthill, additionally populated by Western camera teams, who were transmitting images around the globe in real time.

Today was the day—the guest of state was due to arrive.

The woman had now been standing for over five hours on Chang’an Street, near the Great Hall of the People. She knew that the convoy with the guest of state would drive past. She often felt like she was about to pass out, but she had come to see him, to catch a fleeting glimpse of the man who, more than anybody else, represented the hope of change for her and all the other people assembled today.

Two years ago, she had graduated from the medical school of the renowned University of Wuhan at the top of her class, and now she was working at the university hospital there. Naturally, she had been allowed to attend the university in the first place only because her family’s steadfast loyalty to the Party was widely known. But during her years at the university, she had also come into contact with other thoughts—those of Western philosophers from both antiquity and modernity. She and her friends had spent long nights debating freedom and democracy, and they had asked themselves how their own country’s social and political system might be changed so that there would be less dirigisme, less servitude, and—above all—less nepotism and corruption.

And then, in the motherland of the dictatorship of the proletariat, of all places, something had changed decisively—a new man had taken power, a man who had recognized that things could no longer continue this way. A man who was obviously serious about reform. Initially, she had taken note of the new Soviet government with a shrug, but then she had followed it with greater and greater interest as the new, comparatively youthful head of government attempted to break up his country’s encrusted structures. It registered with her that a similar trend was also emerging in other countries within his empire’s orbit.

The debates and discussions with her friends had grown bolder and more passionate. And these exchanges didn’t cease after she graduated. A previously unknown euphoric mood, hesitant at first and then ever more overpowering, had gripped the country’s youth. It finally leaped out of the university into other domains. Could reform be possible? Might it even be within their grasp? Freedom! Freedom—in our country too?! The past year had already witnessed large, scattered demonstrations in Hefei, Shanghai, and other university cities. Wuhan, too, had seen individual rallies, which initially she had merely watched, but then, out of absolute conviction, eventually joined. The government had shown restraint in exercising its power, and this forbearance encouraged both her and the others to embark upon even more intense political commitment. General Secretary Hu Yaobang, in particular, had shown them a great deal of understanding. Too much so, for at the beginning of the year, the patriarch Deng had forced him to resign. And now, just three years later, Hu was dead.

Still, it had been too late. The thirst for freedom could no longer be stopped by the Party, for young people from all across the country had assembled at Tiananmen Square a month ago to mourn Hu’s death and to make strident calls for freedom. And now she stood here, on the dusty street with all the others, to catch a glimpse of Mikhail Gorbachev. To see, for at least a brief moment, the man who had unleashed the hope for freedom.

Suddenly the crowd stirred. The convoy transporting the guest of state approached. A large man next to the young woman rudely shoved her aside, but then had second thoughts and offered to lift her onto his broad shoulders. A box seat! The motorcycles were already buzzing past. Yes, Mikhail Gorbachev waved to her and smiled. She felt as though he wanted to stop, maybe to shake her hand, but the car’s driver stubbornly stared ahead, and the convoy promptly disappeared in a cloud of dust. Had he really smiled at her? What a strange encounter! In the car, the powerful man with the distinctive birthmark, and on the shoulders of a stranger, Shenmi, a diminutive, dainty woman in the crowd. Here fate had, in the wink of an eye, brought together two people destined—each in their own way—to change the world. And although Mikhail Gorbachev was already effecting changes, her time had not yet come.

Later, as she lay in her aunt’s guest bed, staring at the ceiling, she knew she would once again go to Tiananmen Square the following morning. She would go there for as long as it took for the winds of change to blow across China too.

The next morning, her aunt, the sister of her deceased mother, looked at the young woman quizzically. “Well? Did you see him?” she asked excitedly.

“Yes, he even waved and smiled at me! Auntie, I wish that we had someone like Chairman Gorbachev in our government. Instead, we have that shrimp Deng, who’s trying to use money to subdue our drive for freedom! Special economic zones! Economic openness! Money! Consumerism! What a bunch of crap. What about real freedom for us? Democracy and self-determination?! And when is this unspeakable corruption that’s eating our country alive going to stop?”

Enraged, the young woman clenched her fists. Her aunt looked at her pityingly. “Oh, child. Democracy … That’s something for people in America. For a country like China, with so many people, it’s impossible—it would lead to nothing but chaos, and truth be told, in our history we’ve really had more than enough of that. I do understand that a lot of things here seem too rigid and strict to you and your generation. But also, you weren’t around to experience the confusion before our People’s Republic was founded. The adversity and the many, many deaths. Even afterwards, it was still very difficult for the Great Chairman to defend our nation against both foreign and domestic enemies and to alleviate the misery that was everywhere to be seen. I’ve seen so many people die in my lifetime. But that’s past now, and we have the Party and our leaders to thank for it.”

“Yes,” Shenmi replied defiantly. “But that was long ago. We’re living in the present, not in the past. And the future lies before us. We can’t just stand still, stuck where we are now. No, Auntie, the moment has come. We’ve got to open a new chapter, and we—the people gathering at Tiananmen Square every day—we’re going to be the ones with the guts to take the first step!”

As she spoke, she jumped up, planted a quick kiss on her aunt’s lined face, and disappeared out the door. Looking through the small, dusty window, her aunt watched her receding figure for a long time. New worry lines joined the existing ones. She had promised her sister she would look out for Shenmi carefully. Yet now, with every passing day, her aunt felt less and less certain of being able to keep this promise. What kind of crazy times were these?! And in crazy times, death always appeared on the horizon—that much she had learned in her long life.

Upon reaching the enormous square, Shenmi had a feeling similar to one just a few days earlier. Even more people had assembled there now. The square was black with the throng. She thrust her way purposefully towards the hunger strikers congregated around Chai Ling, who was actually a student majoring in psychology. But here, Chai Ling was a spokeswoman for the peaceful protest; she had called the hunger strike to pressure the Party leadership to enter into a dialogue at long last.

Upon seeing Shenmi, Chai Ling smiled wanly. It was obvious that besides hunger, the heat had already taken quite a lot out of her. A worried Shenmi first checked Chai Ling’s pulse and blood pressure, then said sternly, “This is starting to go too far. You’ve also got to consider that you have another job here besides starving to death! What are we going to do if you’re sidelined, and maybe the other two?!” Shenmi was referring to Wang Dan and Wuer Kaixi, who, together with Chai Ling, had been elected as leaders by the protesting students over the past few days.

Wang Dan, lying on a cot within earshot, grinned and said, “Well, you just go to Deng and put in a good word for us!”

“That isn’t funny,” she replied.

“You know perfectly well that we have the perfect opportunity now because Gorbachev is finally there. There are so many journalists here from all over the world; the whole world is watching us, and our Party leaders dare not move against us. Now we just have to keep a clear head so that everything stays on track.” Wang Dan’s grin broadened as he added triumphantly, “So what do you think, Shenmi? Do you think we’re stupid? A couple of officials were here today. They invited us to debate with Li Peng on television the day after tomorrow! They’re caving, and we’re going to be there to win! The hunger strike is just to prevent them from changing their minds again. And now, please hand over our breakfast!”

Shenmi was speechless; she had actually pulled it off, the Party was ready to engage in talks! In recent days, she had increasingly dreaded the possibility of the fronts massively radicalizing due to the loss of face that the students had inflicted on the government by occupying Tiananmen Square. And now, just the opposite seemed to be the case. Feeling relieved, she administered the glucose infusions to them both.

Tiananmen Square is the world’s seventh largest, measuring 880 by 500 meters; at 440,000 square meters, it is bigger than fifty-five soccer fields. The square can accommodate around a million people, and its holding capacity was exhausted during the strike. More and more people kept streaming onto the square, and not just students. In some places, famous rock stars like Cui Jian or He Jong appeared, and at one spot, art students from Beijing were exhibiting a Chinese version of the Statue of Liberty. More and more ordinary citizens from Beijing and from across the entire country were declaring their solidarity with the demonstrators, and an almost exuberant mood was prevailing over the square. The atmosphere was more reminiscent of an open-air concert than a trial of strength between a government and its people.

In the Pink House, Shenmi watched the televised debate. Pink House was a barracks, actually painted pink, that served Tsingtao beer and hence enjoyed much popularity among backpacking tourists from all around the world. It also featured a television set, in front of which people had now excitedly gathered. Shenmi hadn’t seen Wang Dan or Wuer Kaixi for two days and was outraged about their weakened condition, caused by the hunger strike. She was even more outraged, however, at how the debate was unfolding. Obviously, both student leaders were quite consciously ignoring the polite honorifics customarily expected in China to be shown towards one’s elders or socially high-ranking people. Thus, the talks began with enmity. Demands were made, which the government’s representatives deftly attempted to dodge. The students reciprocated these evasions by making new demands. In the end, the debate tapered off fruitlessly.

Her mood gloomy, Shenmi walked home to her aunt’s house. Something was wrong. She no longer at all felt the students would prevail. Quite the contrary: The student leaders, weakened by the hunger strike and a bit too smugly certain of victory, had merely unleashed juvenile provocations towards the politicians, who had meanwhile continued evading deftly. To her it seemed as though the latter had long since been making decisions behind the scenes. Drastic decisions, in fact. Li Peng and the others had acted like boxers who lull their opponents into a false sense of security, only to deliver the knockout blow out of nowhere. The two hunger strikers’ behavior had disgusted her—so much so that she determined to stay away from the square for the next few days.

It quickly became apparent that her misgivings had been correct: The guest of state, who had been adroitly shielded from the protestors, had scarcely made his departure when Deng imposed martial law over the city. The long-sought meeting with the government had never taken place. Police were now swarming everywhere, and, increasingly, soldiers, while the vast majority of the international press was leaving. The few international journalists who did remain had their credentials abruptly withdrawn. Deng’s minions simply pulled the plug, and to the world, China once again became the black screen that it had been before the protests.

When Shenmi finally returned to Tiananmen Square a few days later, something had changed: The peaceful, even exuberant mood had yielded to one of fearful tension. The protest leaders were now trying to bolster themselves and the others with inflammatory, increasingly radical speeches. Police officers were once again tussling with civilians after the latter had attempted to reach the square. In some of the square’s access roads, barricades had already been erected; in other streets, squads of army soldiers stood guard, unarmed for the time being but busily entrenching themselves.

Meanwhile, an unspeakable stench was hovering over the square, since the masses of people camping there for weeks had lacked any sanitation facilities. Garbage piles had also reached critical levels. Growing louder among the protesters were some voices making the case for retreat in light of the looming escalation. However, these were being stridently shouted down by the radical groups.

“Don’t go, Shenmi,” her aunt had implored her. “Something bad is in the air. I promised your mother that I would watch out for you. Do you want me to break my word? Please don’t go, I’m begging you!”

“But Auntie, I mustn’t leave the others in the lurch! I promise you I’ll be careful!”

As Shenmi stepped into the street, she stood briefly, taking in the warm, early spring air. The noises of the city and its millions of inhabitants appeared so alien to her for a brief moment.

Was this what she wanted? She had gone to medical school to help people—sick people. And now, again, she found herself among those who actually believed they would be able to grab a moving wheel by the spokes, and it was a gigantic wheel indeed. Who were they, these people who believed from their deepest convictions that they would be able to bend this menacing government colossus to their own will? Only for a moment did she let herself despair, even give up hope. Just a moment, and yet, in her heart, there burned an unending feeling of being lost.

She shook herself roughly and resolved to travel by subway, for her aunt’s sake. In recent days, the streets had increasingly been teeming with the sinister types whom a young woman traveling alone did not want to encounter.

But she quickly realized, however, that such figures were hanging around in the subway too. An unkempt sort with greasy hair approached her from the throng just a bit too quickly. At the back of her neck, he could sense his breath, stinking of garlic. How casually his hand was groping her buttocks! She countered him with a filthy look, which, unfortunately, served only to further embolden the stranger to move closer. Shenmi had to stifle a sudden feeling of nausea; she pushed the man away from her.

“Slut!” he hissed at her, making gestures intended to show her that no Chinese man would take that sort of rebuff from a woman.

Shortly before the train reached Gongzhufen station, Shenmi had had enough. She resolved to get off. While still on the stairway, she heard the commotion on the street above. People were screaming and raving, and she could hear muffled rumbling. As she left the subway entrance, what she saw took her breath away. Hundreds of people were entrenched behind burning dumpsters and buses that had been placed across the street, completely blocking it. Everywhere, stones had been stacked in little piles. In some of the faces, Shenmi saw fear; in others, rage, as well as disbelief. But all of them kept glancing, terrified, in the direction whence the muffled rumbling was coming, like some unnamed threat.

At first, the rumbling had been hardly audible, but now it had swelled to an ear-splitting crescendo, drowning out every other sound, even the screams of fear now emanating from the crowd. The tanks had finally reached the barricade.

Shenmi gasped. These were Army tanks—forces that were supposed to protect her the country! And now they were standing here. Menacing and armed to the teeth, they had targeted their weapons systems at the very people they were actually charged with protecting! Then a stone flew out of the crowd and bounced off the steel hatch of the lead tank. Thud! Then another, and another. Soon, a veritable hail of stones rained down upon the tanks, but their armored plating effortlessly deflected the hopeless attack as though it were merely heavy rainfall.

Then the unimaginable happened: The twenty-millimeter machine guns on the lead tank swung up and opened fire on the demonstrators. Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat! Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat! The devil’s own staccato. Right next to Shenmi, a young man slumped over; another, about to throw a stone, saw his arm get shredded to pieces. The corpses were joined by more and more, falling grotesquely in sync with the machine-gun fire. Panic erupted as the lead tank resumed its course and simply plowed through one of the buses that had been positioned across the street, leaving a gigantic gap.

As though trapped in a nightmare, Shenmi watched as the tank treads spat out body parts. The tank stopped; the hatch opened, and two soldiers climbed out. Evidently, they believed that the people had been intimidated by this brutal procedure—a major mistake. An enraged mob charged at the soldiers, surrounded them, and finally stomped them into a pulp before their comrades could rush to their aid. Now more and more soldiers were jumping out of their tanks, opening fire and mowing down anything still moving while they slowly advanced, forcing the crowd to flee in every direction.

Rigid with fear and terror, Shenmi squeezed herself into the doorway of a house as the soldiers drew closer and closer. She desperately attempted to regain control of herself and feverishly sought an escape route. Escape was now impossible; the approaching soldiers had already advanced too far. But if she stayed put, she would surely be discovered, and it didn’t look like anyone was taking prisoners.

Suddenly, the door behind her opened a narrow crack, and an arm pulled her into a dim house entrance. In the semi-darkness, she was able to make out the silhouettes of a woman and a couple of children. The woman pressed her index finger to her lips and looked at Shenmi imploringly. Outside, heavy boots were drawing near, paused, and then someone began banging and shaking the door. A dog growled menacingly; soldiers were barking orders. After a small eternity, the sound of the steps faded away into the night, and the tanks’ droning grew quieter. For a long time, Shenmi dared not budge, and she strained her ears, listening in the darkness. Shots—many shots—were crackling through the city. Here and there, the deep humming of heavy weaponry and the droning of explosions could also be heard. On top of that, intimidating voices bellowed from loudspeakers, and throughout it all, the groaning of the injured sounded beyond the protective door.

Finally, Shenmi couldn’t hold out any longer. She opened the door to risk a glimpse through the narrow crack to see the street. The barricade was still burning; the enormous hole in the burned-out bus stared at her. Crushed human beings lined the streets—people whose bodies had been ravaged by tank treads with the unmistakable message: “This is what those who dare oppose us can expect.”

Cautiously, Shenmi stepped into the street and looked around in every direction. The soldiers had continued advancing in the direction of Tiananmen Square. She slipped the rest of the way out the door, threw the woman another grateful glance, and crept carefully along the walls of the houses.

Suddenly, she heard soft whimpering. A small foot, moving slightly, was jutting out from under a torn-off car fender. “Hello? Can you hear me? Are you still alive? Are you all right?” she whispered.

Another whimper came by way of reply. Shenmi tried to lift the fender, but it had gotten wedged under the remains of a shattered barricade. Using all her strength, she tried again and again to free the tiny person trapped under the metal, but she simply wasn’t strong enough. Then, suddenly, next to her, stood the woman who had rescued her. Together, they succeeded in lifting the fender and pulling the child out from underneath it—a little boy, perhaps ten years of age. Shenmi saw the large wound in his belly, along with the blood and entrails spilling from it, all of which he was desperately pressing with his little hands.

She knew that he was done for, and wordlessly she took him in her arms. In thrall to some kind of maternal impulse, she protectively laid his little body in her lap as he despairingly watched her with large, terror-filled eyes. And while she sat there and tried to provide a bit of comfort to the delicate, dying body in the throes of its difficult transition, she realized that she would never again be the woman she had been only yesterday.

The woman with the children was long gone when Shenmi could finally think again. She had to get out of here. Now. Who knew what else might happen in this 21st century Asian replay of Hitler’s Night of the Long Knives?1 The regime was avenging itself on students for the loss of face it had suffered.

Shenmi gingerly laid the little boy on the hood of a ruined car. She hoped his parents were still alive—then they would find him tomorrow and would be able to give him a proper Chinese burial, at least. She had to somehow make her way back to her aunt’s house; all she could do was hope that she wouldn’t be stymied by the roadblocks that the army had now erected everywhere.

From the city center, the battle noises were still audible, though their intensity was steadily diminishing as the military broke the back of the resistance. Cautiously, she worked her way westward. The streets were eerily empty and dark. Here and there, the black shadow of a cat flitted by. Only the roadblocks were brightly lighted, and Shenmi could see soldiers waiting, machine guns at the ready, for unwitting protesters on the run. But she wasn’t going to give them any opportunity to catch her. She was quite familiar with Beijing, and she knew how to reach the city’s periphery by avoiding the major thoroughfares, using the narrow side streets and byways instead.

Unfortunately, Shenmi had failed to reckon with the troop commanders who had been deployed to augment the Regular Army units. For they had cast a tight net of agents over the city—agents whose sole task was to conduct surveillance of precisely these small byways and to neutralize any insurrectionists chancing to flee. Suddenly, just as Shenmi had started to fancy herself safe, she was brutally thrust against the wall of a building. She felt something made of steel pressing against her temple.

“ID!” The voice was rough, brooking no backtalk. The man standing behind her had put her in a brutal armlock, and Shenmi groaned in pain.

“It’s in my right pants pocket,” she gasped. The army revolver came away from her temple and disappeared into the man’s jacket pocket, then his hand slipped into her pants and pulled out her ID card.

“Li Shenmi,” he read aloud. “Physician from Wuhan. What are you doing here at this hour?”

Shenmi tried to keep her composure: “Is it forbidden for me to stretch my legs a little?”

Wrong answer—the soldier’s armlock became so hard that she was afraid he was going to break her arm.

“I asked you what you’re doing here. And don’t try to con me. I was following you. I know that you’re coming from the city center, and I know that you’re with the people who put up the barricades!”

Shenmi was seized with fear, a deep, nameless fear. She had seen what these people were capable of doing. And here she was alone with this man, who was already inflicting more pain than she had ever experienced.

“N-no,” she whimpered. “I just happened to be there—all I wanted to do was to help the injured!”

The man let go of her arm, grabbed her long hair, and yanked her head back. Now she could see his eyes, which were drilling menacingly into hers.

“You probably think you can pull this shit on me because you’re cute, right?” He sized her up; Shenmi could glean something sinister in his eyes. Suddenly, he seemed to be possessed of an idea. “Come along!” He dragged her by the hair into a doorway. “Get undressed!” She couldn’t believe her ears. “Get undressed!” The man wouldn’t put up with any arguments, especially since he was now backing up his order with an army revolver.

She looked at him beseechingly. “Please, don’t do this. I didn’t do anything …”

“I said, get undressed!” Using the palm of his hand, he struck her across the face. Mechanically, she began to unbutton her blouse. “What’s taking so goddamned long? Faster!” She felt numb as she finally stood there before him, naked. It was so humiliating. “Turn around!” She heard him open his pants and kept hoping that the whole thing was just some dreadful nightmare. Then he grabbed her and penetrated her. It was agonizing. His panting was the last thing she heard before everything around her sank into a black fog.

When she awoke, she found herself lying naked in a pool of urine, in the same doorway where she had been raped. The agent had disappeared. She was bleeding, although she didn’t feel any pain, probably due to shock. She hunted for her clothes, dressed herself on autopilot, and shuffled off. In the meantime, the noises issuing from the city center had fallen silent.

Undetected, she made it back to her aunt’s house and knocked. As the old lady opened up, Shenmi collapsed.

Later that day, the old aunt sat on the edge of her niece’s bed, a worried look on her face. Shenmi was staring at the ceiling. Please, she thought. Please, no reproaches, no questions. I don’t want to talk now. The aunt, who had already been through so much in her long life, seemed to divine her niece’s thoughts. The old lady’s wrinkled hand, with its rheumatic fingers, gently stroked Shenmi’s forehead. “It’s like back when the Red Guards came,” she said softly. “My dear child, the main thing is that you’re alive. Time will heal everything else.”

Shenmi wanted to appear grateful to her aunt, but she couldn’t summon up the necessary strength. Instead, she turned away and lapsed into uncontrollable sobbing. The protective façade fell away to reveal the deeply degraded, distraught woman underneath. She too, in some way—this was now becoming clear to her—had died the previous night.

Later, she tried for hours to wash away the memory of the night before and the brutal rape. People had often called her pretty, but she now regarded this attribute as a curse. “I no longer want to be pretty in a world so hideous. I no longer want to be a woman in a world where womanhood is defiled!” She took a large pair of scissors and cut off her long hair.

In the closet, she found among her deceased uncle’s clothing an old pair of black pants and a cotton shirt that was much too big for her. Her aunt was taken aback when she saw Shenmi in this getup. “You look like a man! Why did you cut off your lovely hair?”

“What has my pretty face gotten me, Auntie? Now I look like a man, and nobody’s going to harass or attack me out there.” She turned on her heel and regarded her reflection in the mirror. “Doesn’t look so bad, young man,” she said to herself, and she felt her old spirits coming back. “Tomorrow I’m going to Tiananmen Square as a man, and I’m going to have a look and find out what’s happened to my friends,” she said defiantly.

Her aunt grew pale, but she knew that any protesting would be pointless. Even as a child, Shenmi had been notorious among the entire family for her stubbornness. Once she had gotten it into her mind to do something, she saw it through. Persistence, toughness, resilience, and an ungovernable strength of will had always been the governing virtues in her life. Meanwhile, everyone in the family also knew that trying to talk her out of something was an exercise in futility. The old lady recalled how Shenmi, at the age of five, had once run away from home to visit her in Beijing. The girl had simply hidden herself away in the luggage compartment of a bus and traveled to the capital city as a stowaway. Meanwhile, her parents had upended the entire neighborhood in Wuhan searching for her.

Now the aunt looked resignedly at her niece. “Child, don’t go breaking your mother’s heart. Or mine.”

But Shenmi was already busy developing a plan for her excursion. She would camouflage herself as a man harmlessly going about his grocery shopping. She readied two plastic bags filled with groceries and set off on her bicycle the next morning.

The major thoroughfares were almost devoid of automobiles, but a lot of people were out and about on bicycles. Her bike, a model known as a “flying dove”—though its weight hardly did justice to the name—nonetheless served its purpose. It brought her to the city center, and as she drew near, she could now see the ravages of the previous night. Destroyed cars that had been hastily shoved back stood on the sides of the streets, bullet holes riddled innumerable building façades, and the streets were dotted with drying pools of brownish blood. Shenmi trembled. The sentries at the roadblocks were suspiciously observing the civilians pedaling by. Eventually, the streets became so impassable from the ruts left by the tank treads that she ditched the bike and continued on foot.

At one of the roadblocks, a sentry waved her over. “You there! Come here! What have you got in your bags?” He threw a searching glance inside. “Good. Pass. But everything’s closed up there. The entire area around Tiananmen Square is completely cordoned off.” Shenmi nodded overhastily and quickly got away.

Indeed, it was. After a short time, she wasn’t able to go any farther. Shenmi pondered what to do and then turned into a broad street that eventually leads to Chang’an Jie, from where she hoped to catch at least a glimpse of the large square. Up ahead was a pedestrian crossing, but suddenly she heard that rumble, both familiar and terrifying in equal measure—about fifteen tanks were slowly approaching from Tiananmen Square. They were driving in a row, as though in a military parade. Otherwise, the broad street was empty—no cars, no bicycles, not a soul to be seen. Shenmi stood at the side of the street, utterly alone, watching the tanks roll towards her.

She thought of the little boy, with the life going out of his eyes, and at that moment, any fear she might have had vanished. Someone’s got to stop them, someone’s got to stop this insanity