Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Practical introduction to the fascinating world of growing and caring for orchids. Guide to the care and cultivation of 40 orchid species and types. Covers all of the major orchid families. Advice on all aspects of cultivation, from getting started to repotting, dividing, growing from seed, and dealing with pests and diseases. How to choose the right orchid for any climate condition and establish a collection. Everything readers need to know to enter their orchids in competition.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 249

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

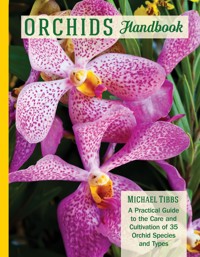

ORCHIDS Handbook

ORCHIDSHandbook

A Practical Guide to the Care and Cultivation of 40 Popular Orchid Species

MICHAEL TIBBS

Paphiopedilum gratrixium, an easy-growing, vigorous, widely cultivated species from Vietnam and Laos.

Orchids Handbook

CompanionHouse Books™ is an imprint of Fox Chapel Publishers International Ltd.

Project Team

Vice President–Content: Christopher Reggio

Editor: Anthony Regolino

Design: David Fisk

Index: Elizabeth Walker

Copyright © 2018 by IMM Lifestyle Books

Orchids Handbook (978-1-62008-305-5) is a second edition of Orchids (978-1-84773-882-0). Revisions include new photographs and updated text.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Fox Chapel Publishers, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

ISBN 978-1-62008-305-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tibbs, Mike, author.

Title: Orchids handbook / Michael Tibbs.

Description: Mount Joy, PA : CompanionHouse Books, [2018] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018032938 (print) | LCCN 2018037289 (ebook) | ISBN 9781620083062 | ISBN 9781620083055 (softcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Orchid culture. | Orchids.

Classification: LCC SB409 (ebook) | LCC SB409 .T582 2018 (print) | DDC 635.9/3472--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018032938

This book has been published with the intent to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter within. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the author, and publisher expressly disclaim any responsibility for any errors, omissions, or adverse effects arising from the use or application of the information contained herein.

Fox Chapel Publishing

Fox Chapel Publishers International Ltd.

903 Square Street

7 Danefield Road, Selsey (Chichester)

Mount Joy, PA 17552

West Sussex PO20 9DA, U.K.

www.facebook.com/companionhousebooks

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Printed and bound in China

20 19 18 172 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Miniature Vanda hybrids and Encyclia tampensis grow happily side by side in a tropical garden environment

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Part One

UNDERSTANDING ORCHIDS

CHAPTER ONE:

AN INTRODUCTION TO ORCHIDS

Structure of the Plant

Growth Habits

Habitat

An Orchid’s Life Cycle

Scent and Color

Mimicry

CHAPTER TWO:

CARING FOR ORCHIDS

Buying Orchids

Choosing an Orchid

Developing Orchids for the Market

Establishing a Collection

Creating the Correct Growing Environment Indoors

Moving Orchids Outdoors

Care and Maintenance Overview

Pests and Diseases

Providing a Controlled Environment for Your Orchids

The Greenhouse

CHAPTER THREE:

CULTIVATION

Repotting an Odontoglossum

“Potting On” a Young Plant

Choosing the Correct Compost

Propagation

Dividing a Cymbidium Plant

Rooting Back Bulbs

Taking Stem (Cane) Cuttings

Removing a Keiki

Seed Propagation

Flasking

Tissue Culture Propagation

CHAPTER FOUR:

SHOWING YOUR ORCHIDS

Award Systems

Orchid Classification

Registration of New Orchid Hybrids

Part Two

ORCHID HYBRIDS

A Note on Orchid Classification

CHAPTER FIVE:

COOL-CLIMATE ORCHIDS

Cymbidium

Odontoglossum Alliance

Disa Uniflora and Its Hybrids

Pleione

Terrestrial Orchids(Cypripedium; Oriental Calanthe; Bletilla; Epipactis)

Zygopetalum

Dendrobium(Cool-Growing Species; Intermediate-Growing Species; Warmer-Growing Species)

Masdevallia(Draculas)

Brassia

Coelogyne

CHAPTER SIX:

ORCHIDS FOR INTERMEDIATE CLIMATES

Oncidiums and Their Intergeneric Hybrids(Tolumnias)

Warm-Tolerant Cymbidiums

Miltonias and Miltoniopsis

Paphiopedilum(Maudiae Group; Cochlopetalum Group; Multiflorals; Brachypetalums; Green-Leaf Species; Parvisepalums)

Lycaste and Anguloa

Bulbophyllum and Cirrhopetalum

CHAPTER SEVEN:

WARM-CLIMATE ORCHIDS

Phalaenopsis (Moth Orchid)

Phragmipedium(Shorter-Petaled Group; Long-Petaled Group; Miniature Green-Flowered; Phragmipedium schlimii)

The Cattleya Alliance(Intergeneric Hybrid Partners)

Catasetum

Vanda and Ascocenda(Basket Culture; Cultivating Miniature Species)

Angraecum and Aerangis

Calanthe

Dendrochilum

Ansellia

Vanilla

FURTHER INFORMATION

GLOSSARY

CITES

CONTACTS

INDEX

PHOTO CREDITS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Oncidium sphacelatum establish into huge specimens and create quite a spectacle when in full bloom.

FOREWORD

Growing orchids has never been more popular. It is truly an international pastime but, strangely, growing orchids is still considered by many to be difficult and expensive. Nothing could be further from the truth. Modern propagation methods—often growing orchids in the laboratory from seed or multiplying the growing tip of a choice orchid in a nutrient medium (meristemming) that encourages the growth of many small plants—has brought tropical orchids within the price range of many people throughout the world. While some orchids are truly difficult to grow, with very exacting demands for their culture, most orchids that can be purchased in nurseries, supermarkets, and florists are easy to grow providing that the instructions on the label are followed. Furthermore, orchids are such good value. Many flower for extended periods—six months’ continuous flowering from a moth orchid is not uncommon.

Orchids are rewarding subjects for both the amateur and for the serious grower. Whether you grow them on the kitchen windowsill, bathroom, garden, or greenhouse, there are orchids that will suit your purpose. Growers often specialize early on—many stay with a particular group of orchids, such as slipper orchids or Masdevallias, while others adopt a more catholic approach and fill their greenhouse with a kaleidoscope of color. With increasing experience, a grower can graduate from the easy moth, jewel, or slipper orchids to the more demanding Dracula, Odontoglossum, or terrestrial orchids. There will be something in the family to satisfy everyone’s taste. If you like large, showy flowers, try Cattleya or Laelia; if you like miniature orchids, then Pleurothallis or Bulbophyllum might suit you better. If you lack a greenhouse, there are plenty of orchids that thrive outdoors and will brighten your garden throughout the spring and summer months.

There are also orchids to suit everyone’s pocket: orchid prices have never been so low. In the 19th century, orchid growing was a rich man’s hobby—now you can now feel just like a Victorian millionaire on a mere fraction of the outlay!

Mike Tibbs, the author of this guide book to growing orchids, is one of the most widely travelled and experienced orchid specialists. Few orchid growers have his breadth of experience, achieved during his career on four continents. He has managed one of the best-known orchid collections in Britain, has worked in both Japan and the USA with major breeders, and has run his own nurseries in South Africa. This book reflects his wealth of knowledge of orchids, from cultivation techniques to plant breeding and showing. In this book he provides a simple, straightforward, and well-illustrated guide to orchids and their cultivation, one that will no doubt increase the number of people taking up orchid-growing as a deeply satisfying and rewarding pastime.

Dr. Phillip Cribb

Honorary Research Fellow at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Rhyncolaelia glauca growing in a tropical garden in Florida.

Part One

UNDERSTANDING ORCHIDS

Renanthera Paloma Picasso 'Flame' (Akihito x storiei).

CHAPTER ONE:

AN INTRODUCTION TO ORCHIDS

Angraecum sesqipedale—endemic to Madagascar, this orchid is often referred to as the Star of Bethlehem or Darwin's orchid.

The Orchidaecae are one of the largest families in the plant kingdom, consisting of over 25,000 documented species, some 800 subspecies, and, at recent count, around 110,000 registered hybrids. Most species occur in the subtropical and tropical regions of Asia, South America, and Central America, but this diverse and adaptable family of flowering plants is found all around the globe, except for the polar regions and most arid deserts. Certain orchids live high in the rainforest canopy clinging to the branches of a host tree, some grow on the forest floor, while others have adapted to living in rock crevices or in decaying organic matter.

While climate change and human interference in natural habitats are contributing to the decline and, in some cases, extinction of certain orchid species, exploration in the depths of the rain forests and previously unexplored parts of Asia and South America are revealing exciting new discoveries. Furthermore, new hybrids are being produced all the time.

Orchid flowers come in a wide array of shapes, sizes, colors, and fragrances, that often challenge easy identification. Among the smallest are the pinhead-sized flowers of the miniature moss orchid (Bulbophyllum globuliforme), while the tiger orchid (Grammatophyllum speciosum), the largest orchid plant in the world, produces between 60–100 single flowers up to 6 in. (15 cm) across on stems up to 6.5–10 ft. (2–3 m) long. Flowers may be blousy and frilly or long and slender, and are produced as a single stately bloom or in a neat row atop an arching stalk. They can be delicately striped, boldly spotted, or lightly dappled, sometimes in magnificently intricate patterns. Colors range from pearly whites, pale green, pink, and yellow to rich shades of magenta, orange, or blue. The deepest red shades are sometimes mistaken for black, but there is no true black orchid.

The flowers emit scents that range from delicately sweet to sharply spicy, musty to putrid. The flowers of Encyclia fragrans produce a strong honey-vanilla fragrance; Paphiopedilum malipoense emits a strong fragrance that can be described as rich raspberry. Less alluring is Bulbophyllum graveolens, which smells like rotting meat.

The leaves, too, vary in size, shape, and markings. Some species, such as the jewel orchid (Ludisia discolor), are prized more for their spectacular foliage than their flowers. Others, such as Microcoelia exilis, have no leaves at all and are intriguing for their tangle of flowering stems and visible roots.

THE CLASSIFICATION OF ORCHIDS

Scientific plant names are subject to rules laid down in the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN), administered by the International Association for Plant Taxonomy (IAPT), and subject to revision every five years.

Unlike most plants, which are described using just the genus and species, many orchids are hybrids and need a hybrid name. So, in addition to being governed by the ICBN regulations, which apply only to plants found in the wild, orchids are also subject to the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants developed for man-made hybrids. The codes were developed to ensure that no two orchids ever have the same name; all orchid names are governed by these codes. Before a new species can be accepted, a scientific name must be described in the prescribed way in Latin and a type specimen cited. The type specimen is usually the first introduction and is often pressed for herbarium collections. To be accepted, the name must be published in a distributed journal, book, or some other recognized publication.

When describing an orchid, the species or genus is followed by a unique name, usually given by the describing botanist. This may represent a characteristic of the flower or plant, its location, or the name of the founder, and is written in Latinized form, even when derived from another language (for example, Cymbidium Cherry Blossom).

The first part of the scientific label is the generic name or genus, i.e. Paphiopedilum (generic names all start with a capital letter). The second part is the specific scientific adjective or epithet that identifies the species within its genus. When a generic name is repeated in a sentence or list it is abbreviated to just the initial capital letter, followed by a period (e.g., Paphiopedilum insigne, P. rothschildianum). Specific epithets, like insigne, are always written in lower case. The first two parts of the name are often followed by a third, frequently abbreviated, that represents the name of the botanist who first described the species.

Botanical classification is done according to a hierarchical system. This means that each higher rank, such as an order or family (see diagram below), includes a number of subordinate groups that share certain characteristics. A family, for example, consists of one or more genera, each having more in common with one another than with the genera of other families. With genera it’s the same, but they comprise one or more related species.

STRUCTURE OF THE PLANT

Orchids are differentiated from other plants by three characteristics that make them unique: their flowers, reproductive parts, and roots.

The Flower

Orchid flowers are uniquely zygomorphic or bilaterally symmetrical: dividing each flower on the vertical plane, and the vertical plane only, will produce two identical halves (other flowers may be divided on any plane to produce two mirror images). The flowers of orchids come in many sizes, colors, textures, and shapes, from magnificently beautiful to curiously bizarre. Within this vast array, the flowers share a common structure—they are made up of three sepals and three petals arranged in a pinwheel or whorl shape, and a reproductive structure called the column.

FLOWER SHAPES: The flowers of different orchid species are easily distinguishable by their shapes. 1. Phalaenopsis; 2. Paphiopedilum; 3. Cattleya.

SEPALS AND PETALS

These form the outer and inner ring of the flower respectively. The sepals sometimes resemble petals in color and texture and are generally equal in size; in some species the uppermost (dorsal) sepal may be slightly larger and more prominent than the lower ones.

The two lower (lateral) sepals may appear fused in some species, but close examination will usually reveal their point of separation. Sepals are usually less flamboyant than petals, but in some species, such as Masdevallia, they have developed into the main attraction of the flower. One petal, most often positioned at the bottom of the flower, is modified into an ingeniously engineered and often spectacularly formed segment called the lip (labellum). Petals and lip are generally, but not always, larger than the sepals.

THE LIP

The lip can be trumpet-shaped, fringed, curved, elongated, or formed like a little pouch. It may be striped or speckled, vibrantly or softly hued. In many orchids the lip is the largest and most ornate feature of the flower, in others it is small and unremarkable. In some species, the lip is fixed and performs its function with decorative lures.

Its purpose is to act as a landing pad for prospective pollinators such as bees, luring them to the flower with extravagant shapes and coloring. To this end, it may appear as a single or multilobed structure, adorned with tufts of hair, bumps, or ridges. In other orchids the lip is engineered to play a more active role in effecting pollination, acting as a trap to prevent the pollinator from leaving the flower until it has collected or deposited pollen.

Many orchid species depend upon a specific pollinator for reproduction; some rely on flies, others on bees, gnats, moths, butterflies, or even hummingbirds. The lip is specifically designed to facilitate this selective pollination process. In many Bulbophyllums, for example, the lip forms a sensitive hinged swing that propels the visiting insect toward the pollen. In the genus Paphiopedilum, one of a group known as slipper orchids, the lip forms a slipper-like pouch that traps the insect until pollination is complete. Several orchid species store nectar in a tube or spur at the back of the lip where it can only be reached by a pollinator with a tongue or other proboscis suited to the length of the spur. Examples are Aerangis and Angraecum sesquipedale, the comet orchid, which possess a long nectar-filled spur. In most orchids, the lip is positioned at the bottom of the flower, a process known as resupination. In bud form the lip is positioned at the top. As the bud matures, it moves 180° and the lip moves to the bottom. A few species, like Encyclia cochleata, are non-resupinate, i.e. the lip remains at the top of the flower and performs its function in a different way, by trapping the pollinator underneath its hood.

THE REPRODUCTIVE PARTS: 1. Ovary; 2. Stigma; 3. Anther; 4. Column; 5. Bract.

The Column (Reproductive Parts)

Most conventional flowers contain both a male organ (the stamen, which contains pollen grains) and a female organ (the pistil, with a stigma that receives pollen grains), and are thus bisexual. Orchids are unique in that their male and female organs are fused into the waxy, tubular structure at the center of the flower called the column.

At the top of the column, pollen grains form golden yellow waxy masses called pollinia, contained in the anther cap. Depending upon the species, there may be between two and eight pollinia. These are attached to a sticky disk and held together by fine threads and protected by an anther-cap, located at the very tip of the column. The pollinia represent the male part of the flower.

Just back from the tip, on the underside of the column, is the stigma or stigmatic surface. Very sticky and highly receptive to pollen, the stigmatic surface represents the female part of the flower.

The male and female segments of the column are separated by a section of tissue, the rostellum, which forms a beak-like structure above the anther-cap. The rostellum prevents self-pollination of the flower and also secretes a glue-like liquid that helps to ensure pollen grains stick to visiting pollinators.

A few orchids, such as Catasetums, are single-sexed, with male and female flowers being produced from time to time, but these are exceptional.

This Phragmipedium flower clearly shows the hair-fringed staminode that protects the pollinia. The staminode acts as a target for prospective pollinators—as they try to land on it, they fall into the pouch below. When they emerge they carry pollen masses which can be deposited on the stigmatic surface of the next flower to be visited, thus fertilizing it.

The Roots

In the plant world, roots serve two basic functions: to anchor the plant in the ground and to absorb moisture and nutrients. This is true of orchids as well, but there are a few different distinguishing characteristics. Orchid roots are generally thicker and appear as individual strands as opposed to the fine, prolific mesh of roots found in most other plants. The fragile inner core of the root is protected by a thick spongy layer of grayish-white protective tissue called the velamen. The velamen is made up of air-filled pockets of dead cells, making the tissue highly absorbent. The outer layer is often covered in fine hair-like projections similar to the absorptive roots of other plants. Throughout an orchid’s life, new roots are produced as the old ones die off.

Microcoelia exilis—a leafless orchid that derives nutrition from decaying leaves, humidity, and rain.

UNDERGROUND ROOTS

The underground roots of terrestrial orchids (those that prefer a ground-level habitat) perform the conventional functions of anchoring and absorbing moisture and nutrients from the soil. These plants may have slender absorptive roots in addition to the thick velamen-covered ones. Some species also develop one or more underground tubers, the fleshy bulb-shaped growths that store moisture and nutrients for the plant during its dormant period, after which new growth appears from the tubers.

This well-rooted Cymbidium has adapted to being cultivated in a pot.

AERIAL ROOTS

Most orchids are epiphytic plants, which means they grow on trees or sometimes rocks. Thick, strong, aerial roots with super absorption capacity allow the plant to attach securely to a host tree and virtually “live on air.” Aerial roots have a green growing tip that is extremely fragile and indicates that the root is actively growing. Aerial roots may grow to several meters in length and are often flattened to provide a firmer grip on the host. An important point is that the aerial roots absorb all the required moisture and nutrients from the air. The host tree acts primarily as support base rather than food source.

Vanda Pachara Delight is a popular Vanda hybrid and can easily adapt to growing on palm trees in a tropical climate. Note its monopodial growth habit.

In certain orchid species that shed their leaves for part of the year or are entirely leafless, such as Chilochistra parishii and related species, the roots contain the chlorophyll required for photosynthesis, the process by which green plants use solar energy to convert water and carbon dioxide into nutrients.

In epiphytic orchids with a sympodial growth habit (see page 21), roots grow from the base of the pseudobulb and the connecting rhizome. In monopodial epiphytes (see page 22), the roots may grow at regular intervals along the stem, or only from the part of the stem just below the leaves.

Some roots take very interesting forms. For example, Ansellia produce side roots with a spiky appearance that grow straight up from the main root, around the base of the plant. Perhaps this unusual growth protects the plant, or helps to catch organic debris to provide additional nutrients for the plant. Whatever the purpose of this bizarre growth habit, it is a feature unique to orchids.

The elegantly striped leaves of Ludisia discolor, also known as the jewel orchid.

The Leaves

Orchid leaves are as diverse as their flowers—they may be cylindrical or broad, paper-thin or thick and succulent, minute or 3 ft. (1 m) or more in length.

Most leaves come in shades of green, blue, and gray, but a special group known as the jewel orchids produce leaves in shades of gray, green, red, or brown, marked with silver, bronze, and copper-toned patterns that are unique in the plant world. Other orchid species are completely leafless.

Leaves may grow in a fan shape from the base of the plant, or alternately up the plant stem at intervals ranging from a few to several centimeters. In many ways, the orchid leaf is the best reflection of a plant’s adaptation to its environment. For example, many species of Vanda grow in shaded environments and their broad, flat, or pinnate leaves are designed for maximum exposure to sunlight.

Brassavolas, which grow in the tropical regions of South and Central America, have fleshy pencil-shaped leaves (known as terete). Their form exposes minimal surface area to the harsh tropical sun and their fleshy substance holds moisture.

GROWTH HABITS

Within the bewildering complexity of forms presented by the orchid family, the growth habits of the plants may be generally classified into two distinct categories: sympodial growth and monopodial growth.

Sympodial Growth

Most orchids have what is called a sympodial form of growth. The main stem of the plant grows horizontally along the surface of support, with branches growing laterally from this main stem from where it produces its flowers. As flowers die the main stem produces new leads, and new growth sprouts from or next to the previous one.

Most sympodial orchids produce thick bulb-like stems called pseudobulbs, (from the Greek word pseudes meaning “false”), so named because they resemble flower bulbs which, in fact, they are not; true flower bulbs are a complete plant in a package. A tulip bulb, for example, contains a tulip in miniature, along with all the nutrients the plant requires to sprout, grow, and flower in the appropriate season.

FEATURES OF SYMPODIAL GROWTH: 1. Leaf; 2. Flower buds; 3. Sheath; 4. Pseudobulb; 5. Bract; 6. New growth.

Pseudobulbs, which store moisture and nutrients for the plant, grow along a fibrous part of the rootstock called the rhizome. In some species, such as Coelogyne or Bulbophyllum, where the pseudobulbs are produced at intervals of approximately 1½–2 in. (3–4 cm), the rhizome is visible. In other species, such as Cymbidiums, the rhizome acts as a very short thread, connecting pseudobulbs that appear to grow in bunches.

Pseudobulbs come in many sizes and shapes. Dendrobium pseudobulbs can be long and thin or short and squat and may grow up to 6 ft. (2 m) in length, whereas Cymbidium pseudobulbs are mostly egg-shaped and may grow from a few millimeters to over 6 in. (15 cm).

Leaves, flower stems, and flowers all develop out of the new growth from the pseudobulb. The new growth will appear from the bulb, fresh leaves will emerge, and a new bulb will form along the rhizome. After supporting the new growth, the existing pseudobulb, now nearly depleted, generally goes dormant and becomes what is called a back bulb. In this phase, the new growth will exploit the last energy resources stored in the back bulb until, when these are exhausted, the back bulb shrivels and dies.

A few sympodial orchids do not produce pseudobulbs. Many species of Paphiopedilum that grow in China, India, and Southeast Asia where moisture levels are high, grow stout shoots from the base of the plant. As the leaves and shoots die, new growth appears from the existing base. Their thick fleshy roots hold whatever moisture reserves they require.

Monopodial growth

In contrast to sympodial orchids that grow horizontally, monopodial orchids grow vertically, with some species reaching quite remarkable heights (many species of Vanda, for instance can grow to several meters tall). Flower stems emerge alternately along a main stem between the leaves. The leaves, which also grow alternately on either side of the stem, may be narrow or broad, widely spaced or compact.

Despite some rather dramatic variations in form, the primary growth feature of monopodial orchids is that new growth develops out of the old growth. New shoots can grow from the end bud of an old shoot, and leaves and flowers are then produced along the new stem.

FEATURES OF MONOPODIAL GROWTH

Monopodial orchids have no pseudobulbs, but tend to have succulent leaves in which they store nutrients and moisture.

HABITAT

Although a few orchid species survive in bogs, marshes, and similar damp conditions, orchids are primarily classified according to their preference for growing on trees, in the ground, on rocks, or on piles of organic decaying material. They are divided into three main groups: epiphytes, terrestrials, and lithophytes.

In certain circumstances there is crossover among the growing habits of these groups. An epiphytic orchid that falls from a tree may grow in the ground below if the conditions are suitable. Likewise, a terrestrial orchid growing near the base of a tree may grow on the trunk and adopt an epiphytic lifestyle. Either will grow on rocks if the opportunity arises and if there is sufficient moisture and nutrients to support growth.

Epiphytes

The word epiphyte is derived from the Greek terms epi (meaning on top, or above) and phyte (meaning plant). The vast majority of orchids are epiphytic. Most orchids grow in tropical and subtropical areas. They represent many of the most spectacular and widely cultivated orchid species.

Epiphytic orchids grow on host trees supported by the trunk and thick lower branches, or perched securely on small twigs in the very top of the canopy. Epiphytes cling to the host tree with very strong roots and take advantage of moisture and nourishing organic debris that may be caught in the crevices of the bark. Additional moisture and nutrients are absorbed from the humid tropical air (air movement is a key requirement for epiphytic orchids).

Chamaeangis odoratissima.

Although epiphytic orchids are not parasitic, the plants do fully exploit the variety of micro-climates offered by an aerial lifestyle. Orchids that prefer shade or moderate light grow on the trunk or lower branches of the tree, while species that crave direct light and ventilation position themselves at the top of their host. Some species select specific hosts for the type of support or shelter they offer and may even be found growing in a particular position, such as on just one side of the tree.

Satyrium coriifolium in its natural habitat after a fire in the Overberg, near Hermanus, South Africa, and its various color forms.

Terrestrials

Terra is the Latin word for earth, so it is logical that terrestrial orchids grow in the ground. In fact, this type of orchid has a remarkable ability to adapt to growing conditions that range from damp forest floors and boggy ravines to sandy dunes and semi-arid deserts.

The roots of these orchids produce tubers that may lie just below the soil surface or deep underground. They store nutrient-laden moisture and provide reserves for the plant during dry spells. Many terrestrial orchids are deciduous: flowers and leaves fade in winter and the plants become dormant underground. When the next growing season begins, new growth appears as a single leafy stem topped by one or more flowers. Terrestrials can grow as solitary individual plants or in impressive colonies, sometimes numbering in the hundreds.

Lithophytes

Generally found in tropical regions, lithophytes take their name from the Greek word for stone. These orchids grow on exposed rock, sometimes making their home on high outcrops. In the manner of epiphytes, their strong roots absorb moisture and nutrients from the air, with additional supplies found in rock crevices where moss and organic debris collect. These orchids often have fleshy leaves or succulent pseudobulbs that store moisture and allow the plant to tolerate prolonged dry spells.

AN ORCHID’S LIFE CYCLE

The life cycle of an orchid is much like that of any other plant: seed is produced and germinates; seedlings mature; the plants flower and then reproduce.

Pollination

The act of pollination sets in motion a chemical reaction that channels the plant’s resources into seed production. The wilting bloom of the flower is the first signal that this process has commenced. When pollination is completed, the sepals and petals begin to shrivel and die. Such a reaction is not at all uncommon among flowering plants, but orchids exhibit extraordinary differences in life cycle habits.

Within a species, the flowering time period may vary significantly after pollination. Equally, the duration of the complete cycle, from pollination to fertilization and the release of seed, may take anywhere from nine to 14 months, with a few exceptions.

Hawk moth (Sphingidae) pollinating a Platanthera. After pollination the seed pod will form. It can take between six weeks and 12 months for the seed to mature, depending on the type of orchid.

Seed Formation and Germination

Seeds form in a capsule behind the flower after pollination has taken place. A common feature among most orchid species is their prolific seed production. The average orchid seed capsule contains multitudes of seeds that appear as very fine, pale yellow dust. Depending on the species, it can take from a few weeks to almost a year for the seed to mature. (Disas take as little as six weeks, whereas Cymbidiums and Cattleyas need up to 12 months to mature.)

As most orchid species are epiphytic (see page 23