9,55 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Fiction

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

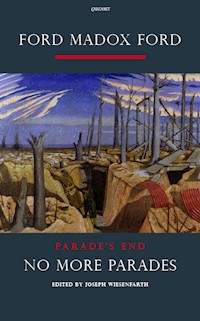

No more Hope, no more Glory, no more parades for you and me any more. 'Nor for the country . . . Nor for the world, I dare say . . .', says Christopher Tietjens to a war-damaged fellow officer, under fire on the Western Front.No More Parades continuesParade's End from Tietjens' return to the Front in 1917. Ford's searing account of the war is unforgettable: supplies are inadequate, orders confused; men die among the 'endless muddles; endless follies'. Death replaces love; Tietjens' betrayal by his wife Sylvia mirrors the violence and dishonour of the war. No More Parades includes: the first reliable text, based on the hand-corrected typescript and first editions; a major critical introduction by Joseph Wiesenfarth, Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and author of Ford Madox Ford and the Regiment of Women; an account of the novel's composition and reception; annotations and a glossary explaining historical references, military terms, literary and topical allusions; a full textual apparatus including transcriptions of significant deletions and revisions; a bibliography of further reading.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

FORD MADOX FORD

Parade’s EndVOLUME II

No More ParadesA Novel

Edited by Joseph Wiesenfarth

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

List of Short Titles

List of Military Terms and Abbreviations

Introduction

A Note on this Edition of Parade’s End

A Note on the Text of No More Parades and the History of its Composition

NO MORE PARADES: A NOVEL

Textual Notes

Select Bibliography

About the Author

Also by Ford Madox Ford from Carcanet Press

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This edition of the second novel of Parade’s End is indebted to the unstinting care given both to it and to me by the editors of the other volumes of the tetralogy. Max Saunders (editor of SomeDo Not …) and I have been discussing Ford Madox Ford, from near and afar, since we met in the mid-1980s at what is now the Carl A. Kroch Library of Cornell University. He was then at work on his definitive biography of Ford and I on Ford’s friendship, personal and literary, with James Joyce. We have discussed and argued amiably over every aspect of this new critical edition of Parade’s End generally, and of No More Parades particularly. His constant attention to the latter’s textual annotation and its informational notes have kept us in almost daily contact as it reached completion. His contribution to it has been such that his name could easily stand next to mine on its title page.

Sara Haslam (editor of A Man Could Stand Up –) has directed my attention as editor of Ford’s England and the English (Carcanet, 2003) to social matters, to passages in others of Ford’s books than this one, and to textual niceties that escaped my eye. Paul Skinner (editor of Last Post) has given particular attention to the two longest chapters of No More Parades (the second chapters of Parts II and III), noting textual nuances that I missed and, as the editor of Ford’s No Enemy (Carcanet, 2002), pointing me to military matters that improved my strategy and tactics in editing this volume. To put it in a sentence, there might have been an edition of No More Parades without my three colleagues’ help, but there would not have been this edition of it without their help.

Finally, on the personal side, Max Saunders, Sara Haslam and Paul Skinner have literally been my eyes through weeks given to cataract surgery and my support through the sudden death of my brother – Charles J. Wiesenfarth, a meticulous craftsman with a love of precision in work and words – for whom there are no more parades but to whom this edition of Ford’s novel is dedicated.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Dust-jacket from the first US edition of No More Parades (A. & C. Boni, 1925)xvi

Ford (on the right) with fellow officers of the Welch regiment. Courtesy of the Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, New Yorkxxiii

Leaf from the original typescript of No More Parades. From the Hemingway Collection, the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Columbia Point, Boston, Massachusettsxlii

LIST OF SHORT TITLES

LIST OF MILITARY TERMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

128s: See A.F.B.

A.C.I.: Army Council Instructions: the Army Council had command of the Army, and issued Orders and Instructions; the latter were more concerned with organisation, training, and logistics.

Ack emma: phonetic alphabet for a.m. (ante meridiem)

A.C.P.: Army Command Pay

Adjutant: officer whose business is to assist the superior officers by receiving and communicating orders, conducting correspondence, and the like (OED 2 Mil.).

A.F.B.: Army Form followed by B and a number; thus A.F.B. 128. These were called ‘attestation papers’ and certified the identity of a soldier, who was always to carry a copy. A duplicate copy was kept on file.

A.P.M.: Assistant Provost Marshal; one who assists a Provost Marshal, who is the head of military police in a camp or in a unit on active service and charged with the preservation of order.

A.S.C.: Army Service Corps

Bandy chair: not a chair but a seat formed by two people linking hands, crossed at the wrist; Cockney slang for a Banbury chair according to A Penguin Dictionary of Historical Slang.

Batman: attendant or orderly who performs a variety of tasks for the officer to whom he is assigned.

B.E.F.: British Expeditionary Force, i.e. the British army sent to France.

Casual battalion: battalion that troops pass through on their way from one station to another; a military entity that facilitates such movements of troops.

C.B.D.: Cavalry Base Depot

C.C.S.: Casualty Clearing Station

Clasp: military decoration: a bar or slip of silver fixed transversely upon the ribbon from which a medal is suspended (e.g. D.S.O with clasp); the medal being given for the whole campaign, the clasps bear the names of those significant operations in it at which the wearer was present (OED 6.).

Colour-sergeant (also colour-serjeant): army sergeant whose special duty is to attend the regimental colours (a flag, ensign, or standard of a regiment) in the field (OED).

D.C.M.: District Court-Martial

Draft: group of soldiers drawn from a larger body of men for a specific strategic or tactical purpose.

D.S.O.: Distinguished Service Order; military decoration awarded for exceptional service during combat in time of war.

Fatigues: the extra-professional duties of a soldier (OED 3.a.)

Flea-bag: a soldier’s sleeping bag (OED flea 6.a.)

Garrison: body of soldiers stationed in a fortress or other place for purposes of defence, etc. (OED 4.†a.)

G.C.B.: Grand Commander of the Bath

G.M.P.: Garrison Military Police

G.O.C.I.C.: General Officer Commanding-in-Chief

G.S.: General Service

G.S.O.: General Staff Officer

H.E.: high explosive

H.Q.: headquarters

I.B.D.: Infantry Base Depot

Indent: to make a requisition on or upon a person for a thing (OED v.5.intr.)

K.C.M.G.: Knight Commander of St Michael and St George

Kitchener battalion: named for General Herbert Horatio Kitchener who, as Secretary of State for War during H. H. Asquith’s term as Prime Minister, recruited an all-volunteer force called the New Army by way of a poster picturing him saying, in effect, Kitchener ‘wants YOU / JOIN YOUR COUNTRY’S ARMY!’ This New Army had no limitations on its deployment and hence, it was hoped, would provide overwhelming power against German forces.

L. of C.: lines of communication

M.C.: Military Cross; decoration awarded to men of any rank – though, at first, captain or below – who showed exemplary gallantry during battle.

Mess: each of the several parties into which a regiment or ship’s company is systematically divided, the members of each party taking their meals together (OED 4.b.).

Militia battalion: army unit composed of ordinary citizens called up for duty as auxiliary forces rather than one composed of professional soldiers.

Mills bomb: type of hand grenade, serrated on the outside to form shrapnel on explosion, invented by Sir William Mills, 1856–1932 (OED).

M.O.: Medical Officer

N.C.O.: Non-Commissioned Officer; enlisted member of the armed forces, including the ranks of sergeant and corporal, who is a link between commissioned officers and the ordinary soldier.

No Man’s Land: space between hostile trenches that neither warring side owned but where many on both sides died trying to capture the trench opposite.

O.C.: Officer Commanding

Parade: assembling or mustering of troops for inspection or display; especially a muster of troops that takes place regularly at set hours, or at extraordinary times to hear orders read, as a preparation for a march, or any other special purpose (OED 2.a.).

P.B.: permanent base

Pip emma: phonetic alphabet for p.m. (post meridiem)

P.M.: Provost Marshal. See A.P.M.

Quarter: short form for Quartermaster, whose duty it is to provide quarters for soldiers, to lay out a camp, and to provide ammunition, rations, and supplies of various kinds.

R.A.S.C.: Royal Army Service Corps; perhaps an anachronism since the R.A.S.C. was not formed until 1918.

R.E.B.D.: Royal Engineers Base Depot

Red Caps: nickname for Garrison Military Police, who have a scarlet flash on their caps.

R.G.A.: Royal Garrison Artillery

R.S.M.: Regimental Sergeant Major

R.T.O.: Railway Transport Officer

Soldier’s Small Book: AB-50 (Army Book-50) was a 32-page book that each soldier was required to carry for purposes of identification and notation, e.g., for making out a will.

V.A.D.: Volunteer Aid Detachment

W.A.A.C.: Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps, established in 1917; duties included cooking, catering, storekeeping, clerical work, maintaining motor vehicles, and a variety of other such non-combat tasks.

Warrant officer: one appointed by an official certificate who is intermediate in rank between the commissioned and non-commissioned officers (OED).

INTRODUCTION

Just as every human face differs, if just by the hair’s breadth turn of a nostril, from every other human face, so every human life differs if only by a little dimple on the stream of it.1

All Rouen is divided into three parts in No More Parades. Part I belongs to Christopher Tietjens; Part II to Sylvia Tietjens; and Part III to General Lord Edward Campion. The first part finds Tietjens at work; the second finds Sylvia at play; and the third finds Campion sitting in judgment on them both. The subject of all three parts is sex and death, madness and parade.2

The three-part structure of No More Parades, the second novel of the Parade’s End tetralogy, shows Ford’s debt to Joseph Conrad, who died on 3 August 1924. In that very month, Ford set to work on Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance,3 which he finished on 5 October 1924. He began writing No More Parades on 31 October 1924. The influence of the biography on the novel is obvious. Ford makes clear in his metafictional memoir of Conrad the individual strengths they each brought to their collaboration on three novels: The Inheritors (1901), Romance (1903), and The Nature of a Crime (1909/1924).4 ‘The writer’, Ford says of himself, ‘probably knew more about words, but Conrad had certainly an infinitely greater hold over the architectonics of the novel, over the way a story should be built up so that its interest progresses and grows up to the last word.’5 And as the typescript of No More Parades shows, it took Ford a long time to get to a satisfying last word – so long a time that it had to wait for the proofs to appear.6

In the broad discussion of the methods he and Conrad agreed upon in writing novels, Ford insists that their strategy was ‘Above All To Make You See’, which is the title of the third part of Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance. And one tactic to put a reader on the spot of the action is to tell the story in conversations. The genius of these, as he and Conrad agreed, was ‘that no speech of one character should ever answer the speech that goes before it’.7 This is so because as one person speaks, the other invariably preoccupies himself with his own thoughts on a subject unrelated to the one under discussion. For instance, although General Campion needs to pass judgment on Tietjens, he puts himself at one remove from him by sending Colonel Levin to speak for him, being too taken up with running an army to do so himself. When Levin speaks to Tietjens on matters related to Sylvia, Tietjens is offended and becomes preoccupied with the proper way to tell the colonel that he is an ‘ass’ without getting himself court-martialled. Thus we have many conversations that move along the action of the novel at the same time as developing nuances in the characters conversing, as we see their thoughts and feelings to be completely at odds with the matter at hand. The cogency of the three-part architectonic structure of No More Parades, and the marital and sexual problems whose constant discussion interferes with the various military problems of the moment, remind us that there was less than a month between Ford’s finishing Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance and his beginning to write No More Parades. The integration between the methodology outlined at length in the one book and the rendering of plot and incident in the other was not lost on the reviewers of No More Parades. Though they may not have made an explicit connection between the two books, they saw brilliance in Ford’s vividly rendering – in his making us see – his subject. And the reviewers’ enthusiasm for the novel helped produce sales that exceeded its predecessor, Some Do Not ….8 Indeed, for many readers No More Parades became their introduction to the tetralogy as a whole.

What Ford was able to do with this overall structure by dramatising the thoughts and feelings of the three main characters and those attached to or dependent upon them – with their ‘interminable worry, frustration, and degeneracy’9 – is give us ‘the first mature, unbiased statement of a clear and comprehensive vision of the World War’.10 He produced ‘a novel of great distinction’,11 a novel that is ‘an amazingly good, an heroic book’12 and ‘far and away the finest novel of the year’.13 Louis Bromfield went further – and also further back – calling it ‘As great as anything produced in English during the past 25 years’.14 ‘As an intellectual feat, the book has few peers’, said Time magazine, adding that ‘consummate art has converted a mountain of material into a story taut as a humming wire, though the spiritual current conducted has terrific voltage’.15 Like these, most reviews of No More Parades were appreciative and laudatory. Indeed, one described it as ‘probably the most highly praised novel of the year’.16 Ford was seen as giving ‘an amazing impression of war’, and ‘those first hundred pages easily surpass in truth, brilliance and subtlety everything else that has yet been written in English about the physical circumstances and moral atmosphere of the war’.17 ‘Mr. Ford has carried the traditional technique of the novel to a point not remote from absolute perfection.’18 ‘It is an astonishing method, and astonishingly effective.’19 ‘Only one writer, James Joyce, knows as much about the technique of writing English as Ford or is able to write perfectly in as many different manners.’ Consequently, ‘there is writing in this book to make the judicious weep – with envy’.20 ‘This is the work of a genius’; therefore, ‘when most war books are forgotten “No More Parades” will survive’21 because it is ‘vivid and brilliant, and startlingly outspoken […] a superlatively fine thing […] written […] with a strength which compels one’s admiration’.22 Combined with Some Do Not …, its predecessor, No More Parades is ‘already an achievement of the order of Marcel Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past”’.23

Ford does not give us Combray as Proust did or Swann’s falling in and out of love with Odette. He gives us Tietjens’ complex social and emotional attachments, first introduced in Some Do Not …, in snatches of memory that set his love for Valentine Wannop against Sylvia Tietjens’ hatred of him, ironically for saving her reputation from ruin. A midnight ride with Valentine contrasts vividly with Sylvia’s beating a bulldog to death because it reminds her of Tietjens. As Combray disappears for Swann, London disappears for Tietjens, with death replacing love on the frozen fields of war. And what better place for every kind and variety of language than an army, with its Welsh subalterns discussing their cows and their wives, a Scots officer gone mad with the noise of war and his wife’s infidelity, Tietjens’ attempting to set down his relations with his wife as a military communiqué, and later, in A Man Could Stand Up –, his composing a proposal to Valentine Wannop for her to live with him in the style of a military order.24 Then there is the overwhelming variety of military abbreviations and acronyms that give the impression of schoolboys learning their A-B-Cs, contrasted with a healthy degree of profanity among the troops that in turn squares off against officers skirmishing with each other as one writes a sonnet in English and the other translates it into Latin. And, of course, there is the expected smattering of French and German spiced with an unexpected dollop of Lancashire to confuse the minds and imaginations of even well-educated men.

This extraordinarily well-received novel opens with Captain Christopher Tietjens, ably helped by Sergeant-Major Cowley, trying to move a draft of 2,994 Canadian troops up the line from the Rouen base camp to the trenches. His efforts are blocked by having orders given and then countermanded; by having inadequate supplies for these troops from a quartermaster who profits by holding them back; by a French railway strike meant to prevent the withdrawal of British troops from the front; and by the interference of the British Garrison Police, who constantly harass the Canadian volunteers whom they wilfully take for conscripts. In addition, Campion has assigned to Tietjens’ staff the shell-shocked and intermittently mad, though highly decorated, Captain McKechnie,25 a classical scholar and proud of it. He has just returned from divorce-leave without getting a divorce. All this while Tietjens’ hut is being shelled by the Germans, whose shrapnel kills O Nine Morgan. He bleeds to death in Tietjens’ arms – Morgan, a Welsh soldier whom Tietjenshas denied leave to settle matters with his unfaithful wife in Pontardulais because he would have been beaten to death by her lover, Red Evans Williams, a prize-fighter. Morgan’s marital troubles as well as McKechnie’s trigger Tietjens’ brooding on his own as he recalls his ‘excruciatingly unfaithful’ wife. She is out and about making trouble for him, after spending some time in a convent, where he ‘imagined Sylvia, coiled up on a convent bed…. Hating … Her certainly glorious hair all round her…. Hating … Slowly and coldly … Like the head of a snake when you examined it….’ The result is that military work that urgently needs to be carried out is interfered with by forces both personal and impersonal. There is sex and death, madness and mayhem constantly to contend with. It is all ‘intense dejection: endless muddles: endless follies: endless villainies’. There are, at the moment, for Tietjens, no more parades.

Nothing that happens here was in any way foreign to Ford. He had enlisted in the army at the age of forty-one in July 1915 and was assigned to the Welch Regiment (Special Reserve) as a second lieutenant. He was sent to Rouen, attached to the 9th battalion,26 and then stationed with ‘battalion transport, near Bécourt Wood, just behind the front line near Albert’, in late July of 1916, during the Battle of the Somme. There he was blown up by a German shell, lost his memory for three weeks, and could not remember his name for the better part of two days. In hospital he saw a soldier die ‘very hard, blood pouring thro’ [his] bandages’. Ford himself, like McKechnie, suffered debilitating shell-shock, which lasted long after he was discharged in January 1919, if H. G. Wells is to be believed: ‘The pre-war F.M.H. was tortuous but understandable, the post-war F.M.H. was incurably crazy.’27 Ford was nonetheless sent to the Ypres Salient in late August 1916, where, among other things, he did not get on with his Commanding Officer. But he was unable to obtain a transfer to a staff job, working with an intelligence unit, because his German ancestry was deemed an obstacle to such a position. Consequently, he was on the scene of the two bloodiest actions of the Great War.

Ford (on the right) with fellow officers of the Welch regiment. Courtesy of the Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

Prior to his enlistment, Ford had separated from his wife, Elsie Martindale, and had been living with Violet Hunt. She proved to be, in part, an adequate model for Sylvia, being as sexually ravenous towards him as she was antagonistic, writing in her diary for 21 August 1917, ‘I hit him & then took him to bed.’28 If Violet did not visit Ford at the Front, she made herself present there by sending her novel, Their Lives, for him to write a preface, which he did under the pseudonym ‘Miles Ignotus’.29 In the last novel of the tetralogy, Last Post, Sylvia does in fact invade Tietjens’ and Valentine’s country house in an attempt to disrupt their union.30 In addition, while living with Stella Bowen and writing No More Parades, Ford had an affair with Jean Rhys, who dramatised it in her particularly vindictive novel Quartet.31 Put briefly, Ford knew enough of sex and death, madness and mayhem to give us the three different parts of No More Parades with the authenticity of life itself. What Sylvia and Campion do, then, can surprise no one who is aware of Ford’s pre-war life, of his service in the British Expeditionary Force in France and Belgium, and of his complicated love affairs after his demobilisation in January 1919.

Sylvia Tietjens appears on the scene in Part II of No More Parades. She comes to France without passport and papers, convinced that the war is a schoolboys’ game played in order to seduce and rape women. Her supposed purpose is to have Christopher sign a document, which in fact requires no signature, that gives her the legal right to live at Groby, his estate, and makes their son Michael successor to it. But the real purpose of her extraordinary adventure is to seduce the husband whom she has not slept with for five years: ‘By God, if that beast does not give in to me tonight he never shall see Michael again.’ But Tietjens’ interest in Sylvia evaporated entirely with her disappearance into a convent of Premonstratensian nuns near Birkenhead. His mind and heart have now settled on Valentine Wannop, who had agreed to be his lover at the end of Some Do Not … although he has never even kissed her. Sylvia nevertheless contrives to get Tietjens to her bedroom at the same time that a former lover and an aspiring seducer appear there, only to have Tietjens forcibly eject them, which brings about his arrest.

This leaves matters in the hands of General Campion in Part III. He has to determine whether Tietjens is guilty of manhandling superior officers without cause and whether he is also guilty of a handful of other accusations that have been made against him as the action of the novel unfolds. Not insignificantly, in the three days that the novel covers, Parts I and II are set in the dead of night and deal with troop movements and shellings as well as with seduction and rape. Part III is set in the morning light; it deals with clarification and inspection. Having satisfied himself of the baselessness of charges against Tietjens, Campion puts Tietjens’ cook-houses on parade: ‘a mustering of troops for inspection and display’.32 In an epiphanic moment, Tietjens sees the pomp and circumstance of this parade as a funeral.

All of which is to say that both Mars and Eros make demands on Christopher Tietjens in No More Parades. The army requires him to feed, shelter, and transport a draft of Canadian troops. His wife requires him to settle their marital and family affairs. The problems that beset him in attending to these matters are so many that he is unable to get to bed for two nights running and fears for his sanity. ‘The martial and the marital: sex and violence’ threaten his body and mind.33 At his weakest moment Tietjens is forced to deal with the importunities of the God of War and the God of Love together, when his godfather, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief Lord Edward Campion, questions him about his marriage and announces his promotion to a post that entails ‘certain death’. This deadly posting as second-in-command of Colonel Partridge’s regiment in the 6th battalion of General Perry, commanding the 16th section, comes about because Tietjens has made his life an insoluble riddle to Campion: Tietjens cannot join the general’s staff because that would smack of nepotism; he cannot join the 9th French Army because a confidential report, prepared by Sylvia’s former lover, Colonel Drake, accuses him of being a French spy; he cannot be sent to the 19th Division of the Fourth Army because Lord Beichan, a meddling newspaper mogul, has placed Second-Lieutenant Hotchkiss in charge of hardening horses for combat. Tietjens despises both men and their works: ‘In their hearts these people are crass cowards walking in darkness.’34 But he cannot stay where he is, doing the splendid job he is doing, because he has physically attacked General O’Hara of the Garrison Police, throwing him out of Sylvia’s bedroom at three in the morning. Campion tells Tietjens that ‘all the extraordinary rows you’ve got into … block me everywhere’. And because Tietjens, no more than Campion, cannot find a way away from death, the general’s order becomes Tietjens’ riddle: How can one be ‘promoted’ to ‘certain death’? It reminds us of the question Sergeant-Major Cowley poses twice in the novel: ‘“Do you know the only time the King must salute a private soldier and the private takes no notice? … When ’e’s dead….”’

Tietjens falls victim to Campion’s riddle of promotion to death because he has not solved a riddle of his own: ‘For it’s insoluble. It’s the whole problem of the relations of the sexes.’35 This problem is personalised for Tietjens in his inability to determine ‘the paternity of his child’: to determine whether he or Drake is the father of Sylvia’s son, Michael. Moreover, no one in the novel has solved the problem of ‘the relations of the sexes’, but Tietjens is the one who pays the price for their failure because, presumably, in being a Christ-bearer (a Christopher) he must fulfil the words spoken about Jesus: ‘They used to say: “He saved others, himself he could not save.”’ Sylvia, who speaks these words, enumerates the ‘others’ whom Tietjens has saved: ‘“He helped virtuous Scotch students, and broken-down gentry…. And women taken in adultery….”’ Sylvia alludes to Tietjens’ saving of Vincent Macmaster, Mrs Wannop, and Edith Ethel Duchemin in Some Do Not …. And No More Parades shows him continuing such activities. He saves the Canadian volunteers arrested by O’Hara’s military police; he saves Cowley from loneliness by celebrating his promotion to lieutenant with him; he saves Colonel Levin’s betrothal party from disaster by promising ‘the disagreeable duchess’ at Lady Sachse’s, bargain-priced coal for her hot houses; he saves Sylvia from ignominy by refusing Campion’s offer of a court-martial to clear his own name by soiling his wife’s reputation. Campion sums up Tietjens’ abilities clearly when he praises him: ‘“He’s got a positive genius for getting all sort of things out of the most beastly muddles…. Why he’s even been useful to me.”’ The other side of it is that Tietjens has got a ‘“positive genius for getting into the most disgusting messes”’. To Campion ‘“Christopher is a regular Dreyfus.”’ Sylvia makes a similar claim. She tells Cowley of Tietjens that ‘“They used to call him Old Sol at school…. But there’s one question of Solomon’s he could not answer…. the one about the way of a man with … Oh, a Maid! Ask him what happened before the dawn ninety-six – no ninety-eight days ago….”’ Ninety-eight days previously at dawn Christopher had heard Sylvia direct a taxi driver to Paddington Station, where she was to take the train to Birkenhead and enter a convent.

The word Paddington echoes through No More Parades. It is the keynote of Tietjens’ freedom. He interprets it as Sylvia’s giving him leave to love Valentine Wannop. But Sylvia has changed her mind and is on the scene again; consequently, Paddington becomes Tietjens’ riddle. What does it mean?

But he had noticed the word Paddington…. Ninety-eight days before…. She had counted every day since…. She had got that much information…. She had said Paddington outside the house at dawn and he had taken it as a farewell. He had … He had imagined himself free to do what he liked with the girl…. Well, he wasn’t…. That was why he was white about the gills….

Tietjens sees that Sylvia has contrived to make a scene ‘before the Tommies of his own unit…. It was a game. What game? … What then was the game? He could not believe that she could be capable of vulgarity except with a purpose.’ Her game is his seduction. But as Tietjens tells Campion, Sylvia has been too artful in her attempt: she has pulled one shower-bath string too many and given him a deadly dousing. Playing bedroom games with Major Perowne and General O’Hara sends her husband ‘up the line’ and out of her reach. Paddington proves a fatal word. It forces him to save her, but himself he cannot save.

Failure to solve the riddle entails ‘certain death’ because of Tietjens’ bad health. If he is not killed in the line, his lungs – ‘all charred up and gone’36 – are certain to give way, and even if they don’t he suspects that his mind will. So No More Parades is a death-haunted novel. It begins with a death and ends with a funeral. O Nine Morgan is hit by shrapnel and dies in Tietjens’ hut; in fact, in his arms, bleeding his life away on Tietjens’ best tunic. Tietjens is obsessed by O Nine Morgan’s death throughout the novel. It recurs to him so insistently that he fears that he has a ‘complex’; indeed, he fears for the balance of his mind. And Morgan’s death spreads out beyond itself to encompass the deaths of many others when, in a lyrical passage, Tietjens meditates on the spectacle of loss:

at the thought of the man as he was alive and of him now, dead, an immense blackness descended all over Tietjens. He said to himself: I am very tired. Yet he was not ashamed…. It was the blackness that descends on you when you think of your dead…. It comes, at any time, over the brightness of sunlight, in the grey of evening, in the grey of the dawn, at mess, on parade; it comes at the thought of one man or at the thought of half a battalion that you have seen, stretched out, under sheeting, the noses making little pimples; or not stretched out, lying face downwards, half buried. Or at the thought of dead that you have never seen dead at all…. Suddenly the light goes out…. In this case it was because of one fellow, a dirty enough man, not even very willing, not in the least endearing, certainly contemplating desertion…. But your dead … yours … your own. As if joined to your own identity by a black cord….37

What Tietjens experiences here is what moved Ford to write that ‘every human life differs if only by a little dimple on the stream of it’ and moved him further to quote Ecclesiasticus in the epigraph of the novel:38 ‘For two things my heart is grieved: A man of war that suffereth from poverty and men of intelligence that are counted as refuse.’ The ‘man of war’ here is Captain Tietjens himself, who is impoverished by his wife Sylvia: ‘she had drawn all the balance of his banking account except for a shilling’. And as one of the ‘men of intelligence’ mentioned by Sirach, he is counted as refuse by his commanding officer, General Campion: ‘he is unsound. He’s too brilliant.’ At the same time that they treat him as they do, Tietjens values a man of intelligence in McKechnie, mad as at times he may be, and men of war in Sergeant-Major Cowley and the 2,994 soldiers whom he has under his command. Indeed, the entire novel is a complex dramatisation of its epigraph. And insofar as Tietjens is treated as refuse, he becomes nothing more than what Ford termed ‘the stuff to fill graveyards’.39

Moreover, insofar as Tietjens’ ‘certain death’ is foreseen in his posting to the line, the last parade in the book is appropriately a funeral; indeed, his funeral. The Tory gentleman, the Anglican saint, must now perish at the front. That persona must die and be buried if Tietjens is to rise again. He cannot come back as an eighteenth-century landholder but must come back as a twentieth-century working man. That, however, strikes Tietjens as reprehensible. ‘Reprehensible! … He snorted! If you don’t obey the rules of your club you get hoofed out, and that’s that!’40 To be reprehensible is to cast off an outmoded code of conduct and to take command of one’s self and live. Reprehensible is the saving word. What Paddington is to No More Parades, Reprehensible is to A Man Could Stand Up –. The former is death-dealing; the latter is life-giving. ‘He was going to write to Valentine Wannop: “Hold yourself at my disposal. Please. Signed …” Reprehensible!’41 But before he can do that there must first be a death of a kind and a funeral of a kind. These begin with the inspection of the cook-houses in which Campion is described as a godhead, Sergeant-Cook Case as his high priest, and the cook-houses themselves as a cathedral. There is an insistence in the novel that soon there will be no more parades at all, civilian or military. This last parade, Tietjens’ burlesque funeral, follows upon Campion’s rejection of Tietjens’ insistence that a gentleman must keep up the parade of his wife’s honour, even if she is a sadistic whore, by not divorcing her: ‘“no man that one could speak to would ever think of divorcing any woman”’. Campion dismisses out of hand this parade as rubbish: ‘“then there had better be no more parades…. Why don’t you divorce?”’ Campion sees that Tietjens’ parade of Sylvia’s honour has contributed to his inability to solve the riddles that cost him his life.

But, in fact, Tietjens, as A Man Could Stand Up – will show us, does not die; but he does go directly to hell in No More Parades:

Es ist nicht zu ertragen; es ist das dasz uns verloren hat … words in German, of utter despair, meaning: It is unbearable: it is that that has ruined us…. The mud! … He had heard those words, standing amidst volcano craters of mud, among ravines, monstrosities of slime, cliffs and distances, all of slime […] and the slime moved […] The moving slime was German deserters…. You could not see them: the leader of them—an officer!—had his glasses so thick with mud that you could not see the colour of his eyes, and his half-dozen decorations were like the beginnings of swallows’ nests, his beard like stalactites…. Of the other men you could only see the eyes—extraordinarily vivid: mostly blue like the sky! […] In advanced pockets of mud, in dreadful solitude amongst those ravines … suspended in eternity, at the last day of the world. And it had horribly shocked him to hear again the German language a rather soft voice, a little suety, like an obscene whisper…. the voice obviously of the damned; hell could hold nothing curious for those poor beasts…. His French guide had said sardonically: On dirait l’Inferno de Dante!

This infernal vision of what Tietjens is to go to contrasts radically with the supernal vision of what he has come from.

Tietjens had walked in the sunlight down the lines, past the hut with the evergreen climbing rose, in the sunlight, thinking in an interval, good-humouredly about his official religion: about the Almighty as, on a colossal scale, the great English Landowner, benevolently awful, a colossal duke who never left his study and was thus invisible, but knowing all about the estate down to the last hind at the home farm and the last oak; Christ, an almost too benevolent Land-Steward, son of the Owner, knowing all about the estate down to the last child at the porter’s lodge, apt to be got round by the more detrimental tenants; the Third Person of the Trinity, the spirit of the estate, the Game as it were, as distinct from the players of the game; the atmosphere of the estate, that of the interior of Winchester Cathedral just after a Handel anthem has been finished, a perpetual Sunday, with, probably, a little cricket for the young men. Like Yorkshire of a Saturday afternoon; if you looked down on the whole broad county you would not see a single village green without its white flannels. That was why Yorkshire always leads the averages…. Probably by the time you got to heaven you would be so worn out by work on this planet that you would accept the English Sunday, for ever, with extreme relief!

Heaven and hell: the country estate and the battlefield: the cricket pitch and the trenches. Heaven is gone and hell is here. The contradiction inherent in the heaven of the one – especially since country estates have fallen into the hands of the Macmasters and the Beichans and will fall into the hands of the De Bray Papes in Last Post – has bred the hell of the other. Now there is only one more parade to attend. That is the inspection of the cook-houses when the godhead – ‘Major-General Lord Edward Campion, V.C., K.C.M.G., tantivy tum, tum, etcetera’42 – descends to officiate at Tietjens’ funeral:

The general tapped with the heel of his crop on the locker-panel labelled PEPPER: the top, right-hand locker-panel. He said to the tubular, global-eyed white figure beside it: ‘Open that, will you, my man? …’

To Tietjens this was like the sudden bursting out of the regimental quick-step, as after a funeral with military honours the band and drums march away, back to barracks.

After his funeral Tietjens is transported to the trenches for burial, and A Man Could Stand Up – begins. And he is buried there in mud by an exploding shell, but rises from it to take command of himself and his battalion and become admirably … reprehensible: ‘Reprehensible! He said. For God’s sake let us be reprehensible! And have done with it!’43 Once that choice is made, clearly, for Christopher Tietjens, there are no more parades.

1 Ford Madox Ford, ‘Epilogue’, in Ford Madox Ford, War Prose, ed. Max Saunders (Manchester: Carcanet, 1999), 63.

2 Madness and parade were discussed at length by Ambrose Gordon in The Invisible Tent: The War Novels of Ford Madox Ford (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1964), 100–18.

3 Ford Madox Ford, Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance (London: Duckworth, 1924).

4 See Joseph Wiesenfarth, ‘Ford’s Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance as Metafiction: Or, How Conrad Became an Elizabethan Poet’, Renascence, 53.1 (2000), 43–60, for the way that Ford wrote his memoir as a novel about writing Romance with Conrad.

5Joseph Conrad 169.

6 This is clearly an inference on my part because we do not have the proofs. But Ford crossed out the last word (indeed, crossed out the last seven lines) of the novel in his typescript. Consequently he had to add the last two sentences in the proofs.

7Joseph Conrad 188.

8 Although David Dow Harvey, Ford Madox Ford 1873–1939: A Bibliography of Works and Criticism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1962), records only one printing in England by Duckworth in 1925, there were five printings by A. & C. Boni in the United States in 1925–6 and an additional printing by Grosset & Dunop, ‘by arrangement with A. & C. Boni’ (n.d. but probably 1927).

9 Edward A. Weeks, Atlantic, CXXXVII (May 1926), 16; review of No More Parades excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 363, #500.

10 John W. Crawford, New York Times (8 Nov. 1925), 9; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 361, #485.

11 Unsigned review, The Independent, CXV (5 Dec. 1925), 650; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 361, #488.

12 P.J.M. Manchester Guardian (9 Oct. 1925), 9; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 359, #478.

13 Isabel Paterson, New York Herald Tribune (22 Nov. 1925), 3–4; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 361, #486.

14 Bromfield, quoted in Time magazine (22 Feb. 1926). Not in Harvey’s Bibliography. See http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,721682-1,00.html, accessed 4 February 2007.

15Time magazine (22 Feb. 1926).

16 Mary Colum, Saturday Review of Literature, II (30 Jan. 1926), 523; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 362, #494.

17 Unsigned review, The Observer (11 Oct. 1925), 4; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 360, #481.

18 Lloyd Morris, ‘Skimming the Cream from Six Months’ Fiction’, New York Times Book Review (6 Dec. 1925), 2; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 361, #490.

19 Gerald Gould, Daily News (28 Sept. 1925), 4; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 358, #472.

20 Burton Rascoe, ‘Contemporary Reminiscences’, Arts and Decoration, XXIV (Feb. 1926), 57; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 362, #495.

21 H. C. Harwood, The Outlook, LVI (3 Oct. 1925), 230; cited in Harvey, Bibliography 359, #477.

22 Ralph Strauss, Bystander, LXXXVII (14 Oct. 1925), 168; cited in Harvey, Bibliography 360, #482.

23 John W. Crawford, New York Times (8 Nov. 1925), 9; excerpted in Harvey, Bibliography 361, #495.

24 ‘Well, then, he ought to write her a letter. He ought to say: “This is to tell you that I propose to live with you as soon as this show is over. You will be prepared immediately on cessation of active hostilities to put yourself at my disposal: please. Signed, ‘Xtopher Tietjens, Acting O.C. 9th Glams’.”’ A Man Could Stand Up – II.vi.

25 The character of McKechnie is undoubtedly drawn from that of another Scotsman whom Ford encountered at Red Cross Hospital II in Rouen and whom he describes in ‘I Revisit the Riviera’: ‘Diagonally opposite me was a Black Watch second lieutenant—about twenty, wild-eyed, black-haired. A shell-shock case. He talked with the vainglory and madness of the Highland chieftain that he was, continuously all day. Towards ten at night he would pretend to sleep’ (War Prose 64).

26 Saunders, Introduction, War Prose 3.

27 Max Saunders, Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life, 2 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), II, 2, 3, 31.

28 Robert and Marie Secor, The Return of the Good Soldier: Ford Madox Ford and Violet Hunt’s 1917 Diary, English Literary Studies No. 30 (Victoria, BC: University of Victoria, 1983), 73.

29 On Ford and Hunt’s love (and hate) affair, see Joseph Wiesenfarth, Ford Madox Ford and the Regiment of Women: Violet Hunt, Jean Rhys, Stella Bowen, Janice Biala (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), 30–60.

30 Violet Hunt invaded Ford’s and Stella Bowen’s country house in Bedham in the autumn of 1920 when Stella was pregnant with her daughter Julie. Hunt also hired some locals to send reports to her about Ford and Bowen’s life together. Her intrusion on them there clearly inspired Sylvia’s intrusion on Tietjens in Rouen and on Tietjens and Valentine in Last Post. See Saunders, Dual Life II 101–2, 249–50; Wiesenfarth, Regiment 59–60.

31 On the Ford–Rhys affair, see Wiesenfarth, Regiment 61–89.

32 Parade (OED 2.a.)

33 Saunders, Introduction, War Prose 19.

34 ‘Preparedness’, in War Prose 72.

35 Ford was not proficient at solving this riddle either. He was said to have been involved romantically with eighteen women and, perhaps, with eleven of them sexually. See Wiesenfarth, Regiment 97.

36 Ford’s words in a letter of 19 December 1916 to Joseph Conrad about his own lungs in Letters of Ford Madox Ford, ed. Richard M. Ludwig (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965), 79; the ampersand in the original quotation has here been changed to ‘and’.

37 Ford wrote about his own experience of mass death in ‘Arms and the Mind/War and the Mind’, saying: ‘And there is no emotion so terrific and so overwhelming as the feeling that comes over you when your own men are dead. It is a feeling of anger … an anger … a deep anger! It shakes you like a force that is beyond all other forces in the world: unimaginable, irresistible….’ (War Prose 41).

38 Ford attributes the epigraph to Proverbs (his title page reads ‘Prov. II vii’ after the quotation), but the quotation is from the Book of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) 26:28, which is ‘modelled in great part on Proverbs’ according to Alexander A. Di Lella, O.F.M. in Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds, The Oxford Guide to the Bible (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 697.

39Thus to Revisit (London: Chapman & Hall, 1921), 203.

40A Man Could Stand Up – II.vi.

41A Man Could Stand Up – II.vi.

42A Man Could Stand Up – III.i.

43A Man Could Stand Up – II.vi.

A NOTE ON THIS EDITION OF PARADE’S END

This edition takes as its copy-text the British first editions of the four novels. It is not a critical edition of the manuscripts, nor is it a variorum edition comparing the different editions exhaustively. The available manuscripts and other pre-publication materials have been studied and taken into account, and have informed any emendations, all of which are recorded in the textual notes.

The British first editions were the first publication of the complete texts for at least the first three volumes. The case of Last Post is more complicated, and is discussed by Paul Skinner in that volume; but in short, if the British edition was not the first published, the US edition was so close in date as to make them effectively simultaneous (especially in terms of Ford’s involvement), so there is no case for not using the British text there too, whereas there are strong reasons in favour of using it for the sake of consistency (with the publisher’s practices, and habits of British as opposed to American usage).

Complete manuscripts have survived for all four volumes. That for Some Do Not … is an autograph, the other three are typescripts. All four have autograph corrections and revisions in Ford’s hand, as well as deletions (which there is no reason to believe are not also authorial). The typescripts also have typed corrections and revisions. As Ford inscribed two of them to say the typing was his own, there is no reason to think these typed second thoughts were not also his. The manuscripts also all have various forms of compositor’s mark-up, confirming what Ford inscribed on the last two, that the UK editions were set from them.

Our edition is primarily intended for general readers and students of Ford. Recording every minor change from manuscript to first book edition would be of interest to only a small number of textual scholars, who would need to consult the original manuscripts themselves. However, many of the revisions and deletions are highly illuminating about Ford’s method of composition, and the changes of conception of the novels. While we have normally followed his decisions in our text, we have annotated the changes we judge to be significant (and of course such selection implies editorial judgement) in the textual notes.

There is only a limited amount of other pre-publication material, perhaps as a result of Duckworth & Co. suffering fires in 1929 and 1950, and being bombed in 1942. There are some pages of an episode originally intended as the ending of Some Do Not … but later recast for No More Parades, and some pages omitted from Last Post. Unlike the other volumes, Last Post also underwent widespread revisions differentiating the first UK and US editions. Corrected proofs of the first chapter only of Some Do Not … were discovered in a batch of materials from Ford’s transatlantic review. An uncorrected proof copy of A Man Could Stand Up – has also been studied. There are comparably patchy examples of previous partial publication of two of the volumes. Part I of Some Do Not … was serialised in the transatlantic review, of which at most only the first four and a half chapters preceded the Duckworth edition. More significant is the part of the first chapter of No More Parades which appeared in the Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers in 1925, with surprising differences from the book versions. All of this material has been studied closely, and informs our editing of the Duckworth texts. But – not least because of its fragmentary nature – it didn’t warrant variorum treatment.

The only comparable editing of Ford’s work as we have prepared this edition has been Martin Stannard’s admirable Norton edition of The Good Soldier. Stannard took the interesting decision to use the text of the British first edition, but emend the punctuation throughout to follow that of the manuscript. He makes a convincing case for the punctuation being an editorial imposition, and that even if Ford tacitly assented to it (assuming he had a choice), it alters the nature of his manuscript. A similar argument could be made about Parade’s End too. Ford’s punctuation is certainly distinctive: much lighter than in the published versions, and with an eccentrically variable number of suspension dots (between three and eight). However, there seem to us four major reasons for retaining the Duckworth punctuation in the case of Parade’s End:

1) The paucity of pre-publication material. The existence of an autograph manuscript for Some Do Not … as opposed to typescripts for the other three raises the question of whether there might not have existed a typescript for Some Do Not … or autographs for the others. Ford inscribed the typescripts of A Man Could Stand Up – and Last Post to say the typing was his own (though there is some evidence of dictation in both). The typescript of No More Parades has a label attached saying ‘M.S. The property of / F. M. Ford’; although there is nothing that says the typing is his own, the typing errors make it unlikely that it was the work of a professional typist, and we have no reason to believe Ford didn’t also type this novel. So we assume for these three volumes that the punctuation in the typescripts was his (and not imposed by another typist), and, including his autograph corrections, would represent his final thoughts before receiving the proofs. However, without full surviving corrected proofs of any volume it is impossible to be certain which of the numerous changes were or were not authorial. (Janice Biala told Arthur Mizener that ‘Ford did his real revisions on the proofs – and only the publishers have those. The page proofs in Julies’ [sic] and my possession are the English ones – no American publisher had those that I know of.’44 However, no page proofs for any of the four novels are among her or Ford’s daughter Julia Loewe’s papers now at Cornell, nor does the Biala estate hold any.)

2) Ford was an older, more experienced author in 1924–8 than in 1915. Though arguably he would have known even before the war how his editors were likely to regularise his punctuation, and had already published with John Lane, the first publisher of The Good Soldier, nevertheless by 1924 he certainly knew Duckworth’s house style (Duckworth had published another novel, The Marsden Case, the previous year). More tellingly, perhaps, Ford’s cordial relations with Duckworth would surely have made it possible to voice any concern, which his correspondence does not record his having done.

3) On the evidence of the errors that remained uncorrected in the first editions, the single chapter proofs for Some Do Not …, and Ford’s comments in his letters on the speed at which he had to correct proofs, he does not appear to have been very thorough in his proofreading. Janice Biala commented apropos Parade’s End:

At the least, he was more concerned with style than with punctuation.

4) Such questions may be revisited should further pre-publication material be discovered. In the meantime, we took the decision to retain the first edition text as our copy-text, rather than conflate manuscript and published texts, on the grounds that this was the form in which the novels went through several impressions and editions in the UK and the US during Ford’s lifetime, and in which they were read by his contemporaries and (bar some minor changes) have continued to be read until now.

The emendations this edition has made to the copy-text fall into two categories:

1) The majority of cases are errors that were not corrected at proof stage. With compositors’ errors the manuscripts provide the authority for the emendations, sometimes also supported by previous publication where available. We have corrected any of Ford’s rare spelling and punctuation errors which were replicated in the UK text (the UK and US editors didn’t always spot the same errors). We have also very occasionally emended factual and historical details where we are confident that the error is not part of the texture of the fiction. All such emendations of the UK text, whether substantive or accidental, are noted in the textual endnotes.

2) The other cases are where the manuscript and copy-text vary; where there is no self-evident error, but the editors judge the manuscript better reflects authorial intention. Such judgements are of course debatable. We have only made such emendations to the UK text when they are supported by evidence from the partial pre-publications (as in the case of expletives); or when they make better sense in context; or (in a very small number of cases) when the change between manuscript and UK loses a degree of specificity Ford elsewhere is careful to attain. Otherwise, where a manuscript reading differs from the published version, we have recorded it (if significant), but not restored it, on the grounds that Ford at least tacitly assented to the change in proof, and may indeed have made it himself – a possibility that can’t be ruled out in the absence of the evidence of corrected proofs.

Our edition differs from previous ones in four main respects. First, it offers a thoroughly edited text of the series for the first time, one more reliable than any published previously. The location of one of the manuscripts, that of No More Parades, was unknown to Ford’s bibliographer David Harvey. It was brought to the attention of Joseph Wiesenfarth (who edits it for this edition) among Hemingway’s papers in the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library (Columbia Point, Boston, Massachusetts). Its rediscovery finally made a critical edition of the entire tetralogy possible. Besides the corrections and emendations described above, the editors have made the decision to restore the expletivesthat are frequent in the typescript of No More Parades, set at the Front, but which were replaced with dashes in the UK and US book editions. While this decision may be a controversial one, we believe it is justified by the previous publication of part of No More Parades in Paris, in which Ford determined that the expletives should stand as accurately representing the way that soldiers talk. In A Man Could Stand Up – the expletives are censored with dashes in the TS, which, while it may suggest Ford’s internalising of the publisher’s decisions from one volume to the next, may also reflect the officers’ self-censorship, so there they have been allowed to stand.46

Second, it presents each novel separately. They were published separately, and reprinted separately, during Ford’s lifetime. The volumes had been increasingly successful. He planned an omnibus edition, and in 1930 proposed the title Parade’s End for it (though possibly without the apostrophe).47 But the Depression intervened and prevented this sensible strategy for consolidating his reputation. After Ford’s death, and another world war, Penguin reissued the four novels as separate paperbacks.

The first omnibus edition was produced in 1950 by Knopf. This edition, based on the US first editions, has been reprinted exactly in almost all subsequent omnibus editions (by Vintage, Penguin, and Carcanet; the exception is the new Everyman edition, for which the text was reset, but again using the US edition texts). Thus the tetralogy is familiar to the majority of its readers, on both sides of the Atlantic, through texts based on the US editions. There were two exceptions in the 1960s. When Graham Greene edited the Bodley Head Ford Madox Ford in 1963, he included Some Do Not … as volume 3, and No More Parades and A Man Could Stand Up – together as volume 4, choosing to exclude Last Post. This text is thus not only incomplete but also varies extensively from the first editions. Some of the variants are simply errors. Others are clearly editorial attempts to clarify obscurities or to ‘correct’ usage, sometimes to emend corruptions in the first edition, but clearly without knowledge of the manuscript. While it is an intriguing possibility that some of the emendations may have been Greene’s, they are distractions from what Ford actually wrote. Arthur Mizener edited Parade’s End