17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: anna ruggieri

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

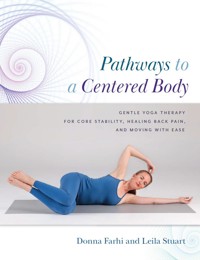

Pathwaysto a Centered Body

GENTLE YOGA THERAPY FOR CORE STABILITY, HEALING BACK PAIN, AND MOVING WITH EASE

Donna Farhi and Leila Stuart

Illustrations by Sonya Rooney

PATHWAYS TO A CENTERED BODY: Gentle Yoga Therapy for Core Stability, Healing Back Pain, and Moving with Ease. Copyright © 2017 by Donna Farhi and Leila Stuart.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information, address Embodied Wisdom Publishers Ltd, 140 Ashworth Bush Road, RD 7 Rangiora 7477, New Zealand.

www.embodiedwisdom.pub

Illustrations by Sonya Rooney, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Photographs by Murray Irwin, Mannering & Associates Ltd, Christchurch, New Zealand

Cover and Text Design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

www.gopated2inc.com

Printed in China.

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN978-0-473-39540-7

Title Pathways to a Centered Body: Gentle Yoga Therapy for Core Stability, Healing Back Pain, and Moving with Ease.

Authors Donna Farhi and Leila Stuart

Format Epub

Publication Date 05/2017

Disclaimer

The information provided in this book is not intended as a substitute for the medical advice of physicians or other qualified health professionals. This book is not intended to diagnose or treat any medical condition, but rather to describe one approach to healthy movement function. The reader is advised to regularly consult a physician in health matters, particularly for diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition and before undertaking the practices in this book. The publisher and authors are not liable for any injuries, damages, or negative consequences allegedly arising from reading or using information in this book.

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1:Introduction

The Core and the Psoas

Six-Step Protocol

1. Find It

2. Soften and Hydrate It

3. Release and Lengthen It

4. Balance It

5. Strengthen It

6. Move from It

A Broader Definition of Core Stability: A Koshic Perspective

1. Physical Body (Annamaya Kosha)

2. Energetic Body (Pranamaya Kosha)

3. Body of Feeling and Emotion (Manamaya Kosha)

4. Body of Thought (Vijyanamaya Kosha)

5. Body of Liberation (Anandamaya Kosha)

Body Weather Reading: The Importance of Baseline Perception

SIDE BAR: How to Use This Book

CHAPTER 2:The Anatomy of the Psoas

Multiple Functions of the Psoas

SIDE BAR: Helpful Anatomical Terms

SIDE BAR: Psoas as Filet Mignon

The Iliopsoas Complex

SIDE BAR: Finding a Neutral Pelvic Position

Movement Function of the Psoas

SIDE BAR: Red Flags

Cohesion and Core Initiation of Movement

SIDE BAR: Body Stories: Standing up Straight for the First Time

Spinal Stability and Upright Posture

The Psoas and Sacroiliac Stability

Fascia and the Psoas

The Psoas and Breathing

The Psoas and Heart Health

The Psoas and the Nervous System

SIDE BAR: The Psoas, Vagal Tone, and Heart Rate Variability

The Psoas, Healthy Organs, and Lymphatic Function

Energetic Anatomy of the Psoas

Summary

CHAPTER 3: Foundation Practices

Integrating Breath and Core Engagement

Abdominal Breathing

Diaphragmatic Breathing

Breath Restriction

INQUIRY:Activating Diaphragmatic Breathing

Powerful Breath (Ujjayi Pranayama)

Practices

Constructive Rest Position

SIDE BAR: Body Stories: Embodying Emotions

Variations of Constructive Rest Position

Variation A—Psoas Awareness with Muscle Release Ball

Variation B—Hyperlordosis (Increased Lumbar Curvature)

Variation C—Pelvic, Sacroiliac, and Lower Back Instability

Variation D—Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

INQUIRIES

Finding Your Psoas

Locating the Attachments

Breathing Into the Psoas Muscles

Accessing the Psoas with Diaphragmatic Breathing

Tracing the Psoas with Hip Flexion

SIDE BAR: Body Stories: Learning To Be Gentle

Restoration

No Pain Is Your Gain

CHAPTER 4:Soften and Hydrate

The Importance of Warming Up

INQUIRIES

Regular Walking

Pulsing the Psoas

SIDE BAR: Body Stories: The World of Walking

Practices

Hydrating the Psoas and Spinal Muscles

Prone Half-Butterfly with Muscle Release Ball

Prone Half-Butterfly with Hip Slides

Upward Puppy Spirals

Downward Facing Corpse Pose (Adho Mukha Savasana)

Practice Summary

CHAPTER 5:Release and Lengthen

How Did It Get So Tight?

SIDE BAR: Too Tight, Too Loose

Practices

Lengthening the Psoas

Variation A—Lengthening the Psoas

Variation B—Lengthening the Psoas with Pelvis Lifted

Variation C—Lengthening the Psoas with a Partner

Half Bow (Ardha Dhanurasana) with Isometric Release

Half Bow (Ardha Dhanurasana) Variation with a Towel

High Lunge at the Wall (or with a Chair)

Releasing the Psoas on a Bolster

Thunderbolt Variation with a Partner

Cobra Pose (Bhujangasana)

Variation A—Cobra Pose with Blankets

Variation B—Cobra Pose with One Bent Knee

Variation C—Cobra Pose with a Bolster

Therapeutic Psoas Release

Therapeutic Psoas Release Variation with Weight

Practice Summary

CHAPTER 6:Balance

Working toward Symmetry

INQUIRIES

Assessing Body Balance

Standing Body Scan

Supine Body Scan

Assessing Your Psoas

Practices

Spinal Release on the Chair

Variation A—Symmetrical Traction

Variation B—Asymmetrical Traction

Balancing Quadratus Lumborum

Asymmetrical Corpse Pose (Savasana)

Practice Summary

CHAPTER 7:Strength: Activating the Core Cylinder of Support

Conscious Activation of the Psoas Muscles

INQUIRIES

Activating Your Psoas

Psoas Coiling

Putting It All Together

Tracing the Cylinder of Support

The Thoracic Diaphragm

Transverse Abdominis

INQUIRIES

Activating Your Transverse Abdominis

Posterior Inferior Serratus—The Secret Helper

Activating Your Posterior Inferior Serratus and Friends

Multifidus

Activating Your Multifidus

The Pelvic Floor

Activating Your Pelvic Floor

Switching on the Core Cylinder of Support

The Figure-8 Loop—Engaging the Core through Dynamic Imagery

The Figure-8 Loop Mantra

Yield Supports Push Supports Reach

SIDE BAR: Using Sound and Breathing to Increase Core Awareness

Practices

Core Toning with Block

Reclining Bound Angle (Supta Baddha Konasana)

The Drawbridge

Variation A with a Belt

Variation B with Knees Drawn

Variation C with Leg Extension

Heel and Toe Touches

Heel Touches

Toe Touches

Bridge Pose (Setu Bandhasana)

Variation A—Low Bridge Pose

Variation B—Dynamic Bridge Pose

Variation C—High Bridge Pose

Drawing Circles

Time to Relax

The Great Rejuvenator (Viparita Karani)

Practice Summary

CHAPTER 8:Containment: How to Safely Open Your Hips

Stability and Mobility

Creating Healthy Hip Mobility

INQUIRY:The Pelvic Reset: Aligning and Stabilizing Your Pelvis

Abduction (Pressing Outward)

Adduction (Pressing Inward)

Alternating Abduction and Adduction

Finish the Sequence

Practices

Mobilizing the Hips: Supine Big Toe Pose (Supta Padangusthasana)

Variation A with Hip Flexion

Variation B with Hip Turned Outward

Variation C with Hip Turned Inward

Variation D at the Wall

Variation E with a Belt

Completion

Practice Summary

Lifelong Strength and Mobility

CHAPTER 9:Practicing Yoga with Core Awareness

Integration and Transformation

SIDE BAR: Emotional Transformation

INQUIRIES

Engaging Your Psoas

Engaging Your Psoas during Forward Bending

The Yoga Postures

Practices

Simple Warrior Pose I (Virabhadrasana I)

Horseman’s Pose (Utkatasana)

Warrior Pose II (Virabhadrasana II)

Warrior I Flow Sequence (Virabhadrasana I Vinyasana)

Half Reclining Hero’s Pose (Ardha Supta Virasana)

Variation A with Leg Extended

Variation B with One Leg Bent

Variation C with Knee to Chest

Gateway Pose (Parighasana)

Downward Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Savasana)

Sage Pose (Bharadvajasana)

Corpse Pose (Savasana)

Practice Summary

Practice Sequence A: Building Strength

Practice Sequence B: Core Yoga Basics

Practice Sequence C: Building Flexibility

Practice Sequence D: Office Workers’ Spinal Recovery

Practice Sequence E: The Decompression Series

Practice Sequence F: Balancing Scoliosis

Practice Sequence G: Sacroiliac Discomfort and Sciatica

Practice Sequence H: Weekend Warrior Repair Kit

Practice Sequence I: Relieving Low Back Pain

Chapter Notes

CHAPTER1

Introduction

IN RECENT TIMES, core fitness has become a catch phrase for a multitude of physical fitness regimens geared toward firming and strengthening the core muscles of the body. With increasingly sedentary lifestyles and the accompanying epidemic of obesity that has followed, core fitness has become almost synonymous with losing weight and regaining a trim, flat, and defined waistline. For some of us, improving core strength and stability offers the promise of alleviation of back pain, allowing us to move through the day with less discomfort or to resume activities, such as running or playing golf. For athletes, dancers, and practitioners of Yoga, having a strong core may translate into having more refined control of the body and the ability to do breathtakingly virtuosic movements. But what do we really mean when we talk about having a strong core? Why is it important to center the pelvis and to have stability in the core muscles of the body? And what muscles are we actually referring to when we speak of the core?

As practitioners and teachers of Yoga with more than five decades of combined experience, we have observed this trend and believe many of the approaches to core fitness, and the movement disciplines catering to its pursuit, often have limited efficacy because they neglect to address the deeper foundation muscles that form the scaffolding for a truly centered pelvis and upright spine. Furthermore, when these deeper core muscles are weak, tight, or unbalanced, strengthening the more superficial muscles of the body may serve only to mask and even accentuate the preexisting body imbalance. The “abs of steel” that have become so much a part of our cultural obsession with the body beautiful actually can contribute to ongoing back pain, shallow breathing, and movement dysfunction. On the other end of the spectrum, we also have seen a worldwide epidemic of hypermobile Yoga practitioners who complain of chronic discomfort and reoccurring injuries. Most of these injuries are the result of the pursuit of extreme flexibility without building a foundation of strong and stable musculature.

THE CORE AND THE PSOAS

This book distinguishes between primary core muscles and secondary core muscles (more about these later). The primary core muscle we’ll be exploring is the psoas muscle (pronounced so-az with a silent p), or more correctly, the iliopsoas muscle complex (Illustration 1). Defined as a “deep” abdominal muscle, the psoas lies in the back or posterior of the abdominal wall and cannot be readily palpated.1 The structure of the psoas is exceedingly complex, and some of the finest anatomists, clinicians, and somatic practitioners have differing views about the movement function of the psoas. These three factors—that is, its deeply buried position, difficulty in palpation, and controversy over its function—go a long way toward explaining why the psoas often is omitted from discussions about core stability and why it has been given so little mention in movement practices and, indeed, in many clinical and therapeutic modalities.

Because of its unique central position and function, the psoas has a multidimensional influence on our experience of stability, strength, ease, and coordination. From their origin in the back of the body, the left and right psoas muscles are anchored to the lumbar spine. The muscles swoop diagonally forward to the front of the pelvis and then make a backward detour to attach to the inside of the thigh bones. Given their distinct angles of pull on the spinal column, pelvis, and hip bones, the psoas are a key determinant of the position of the pelvis and have a profound effect on the functional stability of the body. For this reason, we believe balancing this muscle should precede strengthening of the secondary core muscles. Once the psoas is acting as the primary initiator of core movement, the other secondary core muscles contract in concert to achieve optimal strength and function.

Dr. Janet Travell, coauthor of the classic trigger point manual Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction calls the psoas “the hidden prankster” because of its deeply concealed and difficult-to-access location, and its ability to cause pain that is commonly attributed to other dysfunctions.2 A more apt term might be “hidden treasure” because when patiently released and balanced through awareness and gentle exercises, the psoas can facilitate profound healing and relief from a multitude of discomforts and conditions.

As teachers who have worked with hundreds of Yoga students from all walks of life, it has been our experience that when the psoas does its job in centering the pelvis and stabilizing the lumbar spine, it minimizes the effort of more external muscles. When the psoas is functioning optimally, the pelvis and lumbar spine will be in a neutral position and stabilized from deep within, creating an experience of effortless verticality that is expressed in graceful integrated posture and movement. This physical centeredness can liberate energetic resources and promote a harmonious flow of energy and breath in the body (known as prana within the Yoga tradition or qi or chi in martial arts traditions). Creating core balance also may help you to feel more emotionally secure and able to meet previously overwhelming situations with robustness and resilience. Knowing how to hold your ground may correlate to a powerful psychodynamic stability and imperturbability that gives skillfulness to your speech and action. However we quantify the meaning of core, being centered in the present moment can help us to live from our deepest values and to focus on what ultimately matters.

As Yoga teachers, we are well aware that functionally integrated movement can never be reduced to one muscle. Rather, full movement capacity is the net result of the individual parts of the body working together in a synergistic relationship. So let us be clear at the beginning: we don’t see a competent psoas muscle as a somatic panacea for all that ails you. That would be too simplistic. But we do believe its role in providing an easeful experience in the body has been little understood, and when the psoas is given even a modicum of attention, the results are often quite remarkable. We also believe that many of the methods for releasing the psoas are unnecessarily painful and can contribute to this deep muscle becoming even more contracted. We have seen students with conditions such as chronic lower back pain and unrelenting sciatica, as well as those with long-standing sacroiliac discomfort, feel immediate relief from simple exercises that can be practiced in as few as 5–10 minutes. When you consider that most of the exercises in this book require little more than an inexpensive Muscle Release Ball and a few blankets, that’s a small investment for a big result.3 The accessibility of these techniques can be especially significant for dancers, Yoga practitioners, athletes, and others who may not be able to afford regular bodywork and therefore are highly motivated to manage their own self-care. Many of our students have been surprised to discover that it is possible to correct longstanding conditions, such as hyperlordosis (an accentuation of the lumbar curve), with exercises and supported releases that, when practiced correctly, are without exception pain free.

SIX-STEP PROTOCOL

To fully benefit from this work, we have developed a step-by-step protocol that will build both your cognitive and experiential understanding of the psoas as well as how to access its support. The six steps in this journey are as follows:

1. Find It: It’s difficult to change any part of the body if you don’t know where it is, what it looks like, and how it functions. The field of experiential anatomy (as opposed to purely theoretical study) uses visual imagery of anatomical structure combined with awareness through movement to give a felt experience of body structure. We’ll begin this process by learning about the anatomy of the iliopsoas complex followed by some simple techniques for tracing and locating the muscle. This information is in Chapters Two and Three.

2. Soften and Hydrate It: We believe that stretching any muscle before it has been warmed, softened, and hydrated can contribute to further defensive binding and potential injury of muscle tissue. Unfortunately, many Yoga methodologies do not include sufficient conditioning movements and proceed immediately to static postures that pull on the muscles. Consider how moistened pastry dough can be rolled paper thin, whereas dry crumbly dough cracks and crumbles even with the slightest pressure, and you get the idea. We’ll introduce you to some effective techniques that use pulsing and oscillatory movement to generate circulation of fluid through muscle, fascia, and organ tissue. This information is in Chapter Four.

3. Release and Lengthen It: Incorporating the support of full diaphragmatic breathing, we learn to release and lengthen muscles as a dynamic process of uncoiling followed by slight retraction. Gentle stretching and releasing can further hydrate muscle and fascial tissue. In this section, you’ll learn a veritable treasure trove of both active and passive release positions and techniques for gently and painlessly releasing the psoas muscles. This information is in Chapter Five.

4. Balance It: When significant asymmetries exist between the right and left sides of the body, it makes sense to address these imbalances before strengthening work, otherwise you risk the possibility of simply reinforcing your existing imbalance. Many of the techniques shown in this section can be helpful for those with spinal scoliosis (lateral curvature of the spine) and for one-sided spinal discomfort. This information is in Chapter Six.

5. Strengthen It: This section will teach you to consciously activate the psoas. We will introduce you to the secondary core muscles and explain why coactivation of these muscles is such an important component of spinal health and optimal movement function. Then, the secondary core muscles can work synergistically with the psoas to support dynamic movement. This information is in Chapter Seven.

6. Move from It: This section offers you some suggestions for how to heighten awareness of psoas integration while practicing Yoga postures. Although our emphasis is on Yoga, many of these postures are practiced by athletes, dancers, and somatic practitioners in modified forms. We have also included a special section on how to safely mobilize your hip joints without compromising sacroiliac stability. You’ll find this information in Chapter Eight. Sustaining good posture and movement alignment in all everyday activities reduces the allostatic loading (otherwise known as “wear and tear”) on other body structures, such as knees, hips, and spine, promoting lifelong healthy joints, ligaments, and tendons. This information is in Chapter Nine.

A BROADER DEFINITION OF CORE STABILITY: A KOSHIC PERSPECTIVE

Before we begin learning about the anatomy of the psoas, this introduction would be sorely lacking without at least some mention of the broader definition of core stability. While the subject of this book is primarily the physical dimension of core stability, we recognize the core as a multifaceted experience of self that is centered in the present. From a Yogic viewpoint, the visible physical body is only one dimension of our total embodiment. When we watch an airplane take off, we see the obvious external structure of the plane that is essentially an aluminum cylinder. Yet we’re equally aware that what we can see (the visible plane) is not what gets the plane off the ground. The complex hidden wiring of electrical and computer systems, the engine and jet fuel, and the decisions of the pilot make the plane airborne yet are largely invisible to us. Similarly, our physical structure contains muscles, bones, connective tissue, internal organs, and body fluids, but a larger intelligence orchestrates these raw elements. In the Yogic tradition, we recognize that these invisible elements that operate on the level of the energetic, emotional, mental, and spiritual planes are all interwoven. What Yogis have known for centuries is now being scientifically backed by the discovery that our mind and emotions have a profound effect on our physical body. Conversely, the state of our physical body and health can have both positive and negative consequences on our mental and emotional state, as well as our ability to function in the world.

Although a thorough discussion is outside the scope of this book, we have outlined the geographic mapping of the body from a Yogic perspective and how core stability may be interpreted through this lens. In the Yogic paradigm, the body consists of different sheaths or koshas, which range from the gross experience of our physical structure, such as our muscles and bones, to subtler dimensions of embodiment, such as the flow of breath or a persistent pattern of thought or negative self-belief. Although you can’t measure your thoughts and emotions with calipers, you know how deeply unsettling it can be to move through the day literally “off-balance” because your clear thinking has been eclipsed by a strong emotion such as anger or fear. Similarly, having a mental habit of always “being ahead of yourself” can have you sitting on the edge of your seat, pelvis tipped forward in anticipation of the next moment. The following koshas listed below may give you a broader perspective of what it means to find and sustain a sense of your true center.

1. Physical Body (Annamaya Kosha)

Structural Core Stability is defined as the ability to center your body in a clear relationship to ground, gravity, and space. Bringing awareness to the core structures of the body can assist in the synergistic activation of both primary and secondary core muscles. Your body is then able to organize itself around a fluidly stable and responsive core. This supports you in your ability to transfer and direct force from the feet and legs up into the pelvis and through the spine into space and to mediate the force of gravity coming down through your body with minimal stress through your structure. The practices and inquiries in this book can help you to build structural core stability. Working with your physical body can become a doorway to deeper aspects of your self.

2. Energetic Body (Pranamaya Kosha)

Energetic Core Stability is defined as having a steady, reliable supply of energy to support daily activity. This is not the agitated energy that arises from stimulants such as sugar, caffeine, or alcohol, but a calm vibrant energy that is the result of a well-nourished body and the ability to settle into your center. Eastern traditions call this energetic center the hara or tan dien and both finding and learning to move from this potent center is a lifelong process.4 In Western science, we refer to this center of intelligence as the “abdominal brain” or enteric nervous system, known colloquially as our “gut instinct.”5,6,7 The enteric nervous system of the gut constitutes an independent brain that is in an ongoing communication with the rest of the body.

In the Yogic tradition, the energetic body is understood as prana or life force, the mysterious animating force that orchestrates all the self-regulatory functions of the body, such as the movement of the blood, digestion of food, and elimination of waste. Prana underlies the support for the microcirculation of oxygen and nutrients at a cellular level and is expressed in full-body breathing through the movements of external respiration. These different roads all lead to the same destination: a deep navel center acting as a “Grand Central Station,” coordinating impulses as they move in to and out of a firm center to each of the six limbs (the head, tail, two arms, and two legs). When energetic centeredness is mastered, even the smallest gesture appears to be orchestrated from the vital center, as can be witnessed in the movement of any great athlete, dancer, or martial artist. Although not all of us can become masters, anyone willing to invest a little time and energy can attain better posture and more grace in their movement.

The psoas muscles are the primary physical scaffolding supporting the energetic center. When you establish a stable structure with the help of the psoas, prana can circulate freely throughout your body. Movement that is initiated from your core is more efficient and requires less energy, which leaves more energy for you to enjoy your life.

3. Body of Feeling and Emotion (Manamaya Kosha)

Emotional Core Stability is defined as acquiring the ability to feel a broad range of emotions without losing a sense of a stable unchanging center. Cultivating emotional stability involves learning to welcome, meet, and greet your feelings and emotions through a neutral witnessing process that neither suppresses emotions nor inappropriately vents or expresses these emotions in a way that causes harm to others. Through this process, you learn to view your feelings and emotions as messengers offering valuable information about your experience, without eclipsing an awareness of the unchanging Self. Far from creating a cold-hearted detachment, being able to disidentify with emotions allows you to register your experience in high resolution without shutting down or becoming overwhelmed. This can increase your ability to remain centered and present for others who may be in the throes of their own strong emotional experience.

The psoas can be viewed as a repository of the instinctual emotions of the abdominal brain. Working tenderly with the psoas can sometimes unleash these emotions, but at the same time, it can provide access to the strength and innate wisdom necessary for the healing journey toward emotional wholeness.

4. Body of Thought (Vijyanamaya Kosha)

Mental Core Stability is the ability to establish and sustain the practice of pratyahara. Pratyahara is a Sanskrit term that refers to the restoration of the senses to their fullest function, whereby you begin to notice the unchanging ground from which experience arises. To be truly centered is to have a simultaneous awareness of both the changing patterns of your mind and the unchanging ground of consciousness. Balancing your mental process includes identifying and compassionately looking at the tendencies, habits, and programming that consistently draw you out of your core and prevent the emergence of your deep inner wisdom. Such presence of mind allows you to respond to each situation perfectly and appropriately.

The psoas can register the mental programming and metaphors with which we live, often resulting in excessive muscular tension. For example, if you live with a belief system that no one can be trusted, your vigilance will be embodied as tension in the psoas and other muscles of your body. When the psoas is hydrated and balanced, it can be used as a reliable physical tool to tap into the stillness that underlies and contains all thoughts, feelings, and emotions. It may help to establish a sense of being seated in your Self, accessing and relying on your authentic power and wisdom.

5. Body of Liberation (Anandamaya Kosha)

Spiritual Core Stability is about having a connection to your core purpose or dharma and truthfully maintaining a faithful allegiance to your unique life path. When you live with a sense of connectedness and intimacy with the world and others, ultimately there is no center and no periphery, no you or me, only an indivisible oneness. Working with the psoas can help you to have a felt sense of connectedness within yourself that can overflow into your relationships in the outer world. The physical stability that results from balancing the psoas can even result in feelings of greater connectedness.

One of the most tangible and immediate ways to begin the process of centering yourself is through and in the body. Because each kosha is inextricably linked to all the others, centering the physical body is one of the simplest and most immediate ways of balancing the other koshas. The psoas can function as a “touchstone” for accessing and balancing all the koshas.

Ultimately, it does not matter which door you choose to walk through while in the process of developing a better sense of center, but we encourage you to return again and again to your body as a reference point. Then, as you explore the many experiential inquiries and exercises in this book, take a little time to notice whether the structural work you have done has evoked any change in how you feel energetically, emotionally, mentally, and even spiritually. We call this observational process “body weather reading,” and we encourage you to use this practice not only during and after you complete an exercise in this book, but also frequently throughout your busy day. Learning to recognize when you’ve moved away from center is the first step in finding your way back.

BODY WEATHER READING: THE IMPORTANCE OF BASELINE PERCEPTION

If you’ve ever gone for a walk in a large botanical park, you will be familiar with the maps posted at the entranceways with red arrows declaring “you are here.” Because unless you know the point from which you are starting, it’s impossible to navigate to where you want to go. Similarly, by doing a little body weather reading at the beginning of each practice session and noting how you are feeling, you then will be able to appreciate any changes that occur as a result of your practice. This process can be especially important when you are trying to ascertain which practices are most helpful in ameliorating discomfort and healing injuries. Before you begin a practice session, take a little time (walking, standing, sitting, or lying down) to check in with your self. Using the koshas can be a handy framework for structuring your observations:

■ How do you feel in your physical structure? Note any areas of tension or discomfort.

■ What kind of energy level do you have today? Is your breath rhythmic?

■ Are you aware of any particular feelings or emotions that are visiting today? If so, can you identify the nature of these visitors?

■ Were your spirits high or low this morning? Reflect back to when you woke up.

After you practice an inquiry or exercise, take a few minutes to reflect again: has there been any physical change? If so, can you define it? If you began your session feeling depleted and fatigued, have your energy levels improved? If you began the session feeling anxious and unsettled, do you now feel more grounded? When you come up to standing at the end of each session and begin to move about your day, has your practice made a qualitative difference to the way you are operating in the world? It is through this careful observation and inquiry that you can come to know how to center yourself and to sustain that centeredness even as you step out into the world.

How to Use This Book

To understand the rationale of many of the exercises and inquiries in this book it will be helpful to read the next chapter on the anatomy of the psoas. If, however, you feel intimidated by the subject of anatomy, there’s no harm in skipping this chapter and moving directly to the practices in the chapters that follow. Or, if you want to glean the most important anatomical points, you can read the Key Concepts summarized at the end of each section. Just looking at the pictures or reading the key concepts can offer valuable insights. Once you’ve experienced some of the benefits of the practices, you may become curious about why the exercises are so effective and feel encouraged to take a peek at the anatomy.

If you have an existing Yoga practice, Pilates routine, or other fitness regimen, consider adding one or two exercises to your routine. Take some time to trial those exercises, which will make it easier to discern whether a specific exercise is of benefit to you. Once you become familiar with those practices, explore a new one. Feel free to pick and choose those practices that feel relevant to your goals, but note that our protocol has a logical progression and the exercises have been sequenced accordingly. Eventually, you will develop a repertoire of practices that you can use to meet your personal needs—whether to release a tight back, open your body after sitting at your desk, or strengthen your core to prepare for a challenging athletic event.

ILLUSTRATION 1: Iliopsoas Complex

CHAPTER2

The Anatomy of the Psoas

WE WANT TO tempt you to dive wholeheartedly into this chapter on the anatomy of the psoas by first revealing some of the amazing functions of this muscle. The effort that you put into studying the anatomy (or structure) and the kinesiology (the movement function) of this phenomenal muscle will give you a strong foundation to fully appreciate the broad-ranging capacities of the psoas. Understanding this anatomy also will give you crucial insights into the way the exercises offered in this book will work to release, balance, or strengthen the core body.

MULTIPLE FUNCTIONS OF THE PSOAS

The psoas carries out myriad functions and is truly a Yogic muscle as it serves to unify the body into a cohesive whole (Illustration 1).

The psoas creates a bridge by linking the following (Illustration 2):

■ The upper body to the lower body

■ The core to the periphery

■ The back body to the front body

■ The axial skeleton (spine and pelvis) to the appendicular skeleton (legs and arms)1

The psoas also has multiple functions:

■ Central body support

■ Lumbar stabilizer

■ Regional muscular support for stabilizing the sacroiliac joint2

■ Core initiator of movement

■ Medium for effortless hip flexion and walking

The psoas can have a profound influence on the following:

■ Full diaphragmatic breathing

■ Healthy organ function

■ Balancing the nervous system

■ Psychological stability and resiliency

ILLUSTRATION 2

Helpful Anatomical Terms

Anterior refers to a structure in front of another structure in the body.

Posterior refers to a structure in back of another structure in the body.

Superior refers to a structure closer to the head than another structure in the body.

Inferior refers to a structure closer to the feet than another structure in the body.

Medial refers to a structure closer to the midline than another structure in the body.

Lateral refers to a structure farther away from the midline than another structure in the body.

Unilateral refers to a structure, action, or aspect that occurs on one side of the body only.

Bilateral refers to a structure, action, or aspect that occurs on both sides of the body simultaneously.

Flexion in the spine refers to bending forward. In other joints or body parts, it refers to two body parts moving closer together and decreasing the angle between them (e.g., in elbow flexion the forearm and upper arm come closer together).

Extension in the spine refers to bending backward and in other joints or body parts refers to two body parts moving away from each other and increasing the angle between them (e.g., in elbow extension the forearm and upper arm move further apart).

Lateral Flexion refers to bending a body part to the side.

Rotation refers to twisting or pivoting a part of the body.

Neutral Spinal Curves occur when the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar curves are balanced over a stable pelvis so that the spinal vertebrae have maximum space between them. A neutral lumbar curve is optimal in both standing alignment and functional movement to efficiently transfer force from the spine to the pelvis and legs.

Fascia traditionally is defined as the connective tissue primarily composed of collagen that forms sheaths or bands beneath the skin to attach, stabilize, enclose, and separate muscles and other internal organs. This definition currently is being broadened by findings in scientific and research circles to suggest that “all the collagenous-based soft tissues in the body, including the cells that create and maintain that network of extra-cellular matrix” come under the designation of fascia.3 It may be helpful to imagine the fascia as a three-dimensional web connecting the entire body. A snag or thickening of fibers in one area of the web can have far-reaching consequences throughout the whole fabric of the body.

Ideokinesis is a form of somatic education that first came to prominence in the 1930s, using anatomically based, creative visual imagery to evoke conscious and refined neuromuscular coordination. “Ideo” means idea and “kinesis” refers to movement.

Intervertebral Disks are positioned between the vertebrae of the spine and consist of a tough outer layer called the annulus fibrosus and a soft jelly-like center called the nucleus pulposus. The intervertebral disks act as spacers and shock absorbers: loading weight compresses the disks, and when released, they regain their original shape. Chronic stress caused by overloading the spine, poor posture, or dysfunctional movement patterns (especially repetitive forward, backward, and twisting motions) can weaken the annulus and compromise the central position of the nucleus. In extreme cases, this can lead to disk herniation, whereby the annulus is completely ruptured and the gel of the nucleus leaks out. This can put pressure on the surrounding nerves and can cause severe pain. The malleable disks also contribute to spinal movement and maintenance of the spinal curves. Imagine how little our spine would move without the ability of the disks to stretch and compress.

Somatic refers to practices and approaches to embodiment that invite sensing, feeling, and acting from one’s own sensory awareness. Thomas Hanna, Ph.D. (1928–1990) coined the word “somatics” in 1976 to name the approaches to mind–body integration where the body is experienced from within. “Soma” is a Greek word for the living body.

Psoas as Filet Mignon

To get a fuller appreciation of the sheer heft of the psoas muscles, the next time you are at the supermarket, pick up an entire filet mignon. Although humans certainly are not as large as cattle, seeing the size and feeling the weight of this muscle may give you a better sense of the substantial bulk of your own psoas muscles. Cut in cross-section, the many muscle bundles of the psoas are clearly delineated by the white envelopes of fascia.

THE ILIOPSOAS COMPLEX

Although the three muscles in what is commonly referred to as the iliopsoas complex (psoas major, psoas minor, and iliacus) often are grouped together, each muscle has an individual identity and function. The Latin word psoa means “muscle of the loins” and in cattle is the tender filet mignon cut. In the upright human, the psoas muscle functions as a support structure, and as we’ll soon see, it probably is not very tender in most people.

The largest muscle of the iliopsoas complex, the psoas major is approximately 41 centimeters long (16 inches) and is a thick triangular-shaped muscle that connects the spine to the legs. The psoas major is divided into two parts. The superficial portion arises from the sides of the 12th thoracic and the 1st–5th lumbar vertebrae, as well as the 1st–4th intervertebral disks. The deep portion arises from the transverse processes of the 1st–5th lumbar vertebrae (Illustration 3).

The psoas major journeys from its origin on the spine diagonally forward and laterally over the pubic bone and then dives backward to attach to the inside of the femur by a shared tendinous insertion with the iliacus (Illustration 1). Mechanically, this spatial arrangement allows the psoas to function as a pulley system that significantly increases the strength of the psoas.

ILLUSTRATION 3: Psoas Major Origins to Insertion

The psoas minor is present in less than 50 percent of individuals. It connects the spine to the pelvis and may have been more relevant to four-legged creatures, which may explain the gradual evolutionary disappearance of this muscle in two-legged humans (Illustration 4).4

When present, it arises from the 12th thoracic and 1st lumbar vertebrae and attaches to the rim of the pubic bone via a long, thin tendon. The psoas minor helps to maintain the horizontal alignment of the pelvis. Contraction of the psoas minor can contribute to posterior rotation of the pelvis (as when you tuck the tailbone under) and lumbar flexion (a flattening of the lumbar curve).

ILLUSTRATION 4: Psoas Minor