Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

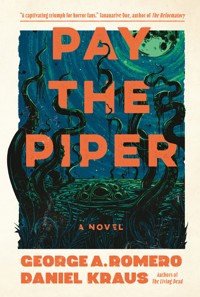

A terrifying tale of supernatural horror set in a cursed Louisiana bayou, from the minds of legendary director George Romero and bestselling author Daniel Kraus. In 2019, while sifting through University of Pittsburgh Library's System's George A. Romero Archival Collection, novelist Daniel Kraus turned up a surprise: a half-finished novel called Pay the Piper, a project few had ever heard of. In the years since, Kraus has worked with Romero's estate to bring this unfinished masterwork to light. Alligator Point, Louisiana, population 141: Young Renée Pontiac has heard stories of "the Piper"—a murderous swamp entity haunting the bayou—her entire life. But now the legend feels horrifically real: children are being taken and gruesomely slain. To resist, Pontiac and the town's desperate denizens will need to acknowledge the sins of their ancestors—the infamous slave traders, the Pirates Lafitte. If they don't . . . it's time to pay the piper.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Praise for George A. Romero and Daniel Kraus’s the Living Dead

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Coauthor Note

Hog Guzzle

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

Queen Cottonmouth

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

PRAISE FOR GEORGE A. ROMERO AND DANIEL KRAUS’S THE LIVING DEAD

“A horror landmark and a work of gory genius marked by all of Romero’s trademark wit, humanity, and merciless social observations. How lucky are we to have this final act of grand guignol from the man who made the dead walk?”

—Joe Hill

“Will play out on the inside of your skull long after you’ve finished it.”

—Clive Barker

“Panoramic and sweeping, a smorgasbord of the undead, a book that will give even the most ardent zombie lovers their fix.”

—New York Times

“The definitive account of the zombie apocalypse. It expands, clarifies, and concludes a tale more than fifty years in the telling, and does so with wit, style, and a deep sense of commitment.”

—Washington Post

“A zombie tale for the ages. This is a rare gem of a story, one that pays homage to its varied source material, while also standing on its own merits. A true gift to horror fans.”

—Library Journal (Starred review, a Top 10 Horror Novel of 2020)

“The last testament of the legendary filmmaker is a sprawling novel about the zombie apocalypse that dwarfs even his classic movie cycle. . . A spectacular horror epic laden with Romero’s signature shocks and censures of societal ills.”

—Kirkus

“Every zombie movie lives in the shadow of Romero, but he never got the budget to work at the scale he deserved. Fortunately, Daniel Kraus delivers the epic book of the dead that Romero began. That shadow just got a whole lot bigger.”

—Grady Hendrix, bestselling author of The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires

“If Night of the Living Dead was the first word in the dead rising field, The Living Dead is the last word. A monumental achievement.”

—Adam Nevill, author of The Ritual

“A posthumous zombie novel as urgent as Romero’s ’60s classics. . . . There are so many sympathetic protagonists that it’s impossible to predict who will survive and who will be eaten.”

—Los Angeles Times

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Pay the Piper

Print edition ISBN: 9781835412428

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835412534

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Text © 2024 New Romero Limited

Cover: Main image by Evangeline Gallagher © 2024 Union Square & Co., LLC

Originally published in 2024 in the United States by Sterling Publishing Co. Inc. under the title Pay The Piper.

This edition has been published by arrangement with Union Square & Co., LLC, a subsidiary of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 33 East 17TH Street, New York, NY, USA, 10003.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Suzanne Descrocher-Romero

COAUTHOR NOTE

For this novel’s portrayal of Cajun speech, I have taken my cue from Mike Tidwell’s Bayou Farewell: The Rich Life and Tragic Death of Louisiana’s Cajun Coast, in which he writes:

Clearly, to write all of the Cajun dialogue in this book . . . would exhaust the reader and prove, in the end, disrespectful to Cajuns. The true color and dignity of their speech would inevitably be lost in translation. Therefore I’ve chosen a more limited portrayal, faithfully omitting the th sound and including some of the altered grammar without laying things on too thick. This approach serves to consistently remind the reader that Cajuns do, in fact, sound different from most Americans without loading the pages down with an impenetrable soup of dialogue.

—Daniel Kraus

HOGGUZZLE

•OR•

KEEPING TRACK OFNASTy-SUGAR

1

Bob Fireman’s Wagon Wheel Carnival had rolled its calliope pennants to the outskirts of Alligator Point’s green inferno every January 8 since—well, no still-living Pointer could recall it not coming. The carny’s clockwork arrival honored an event even kids as small as Pontiac knew. Each year since starting school, she’d heard the same tale from her teacher, Miss Ward.

Under the cold, slithering daybreak fog of January 8, 1815—Miss Ward favored a flowery windup—fifteen thousand musket-wielding British soldiers stormed the only defense shielding New Orleans: an eight-hundred-yard mud barricade. We Yanks had one-third the manpower, a hastily sewn blanket of army regulars, free Blacks, frontier riflemen, Choctaw Indians, and swashbucklers under the Jolly Roger of the Pirates Lafitte. Yet the ragtag throng fell into mystical lockstep under Major General Andrew Jackson, who, in these parts, ran second in celebrity only to Jesus. Two hours later, the Brits paddled home, tails twixt legs. Their dead got pitched down a hole in the Chalmette Plantation battlefield, the only gaffe Jackson made. This was bayou country. The steamy soil said hell no to John Bulls, even dead ones, and pushed those rotting redcoats back into the sweltering sun.

According to Miss Ward, the Battle of New Orleans had been a national holiday, called simply “the Eighth,” for fifty fuck-damn years! (Miss Ward didn’t say fuck-damn, but Pontiac did, quiet, so only Billy May heard.) Somewhere, somehow, January 8 lost its prestige, but that didn’t surprise Pontiac. Things had a way of getting lost down here in the swamp. Louisianans, though, kept the date; folk down here loved their celebrations. Every backwater holler Pontiac tread, she heard the spongy land breathe life back into the vaunted dead.

Jackson: the susurration of sugarcane.

Lafitte: the algae hiss as gators skimmed.

No one held faster to January 8 than Bob Fireman, a fellow who didn’t exist but whose name gamboled across every food stand, sandwich board, and you-must-be-this-tall placard in the carnival. Bob Fireman’s Wagon Wheel Carnival wouldn’t arrive in Alligator Point proper until June 23—a different Louisiana holiday called St. John’s Day. The January 8 carny was a forty-minute walk north in the dry-land town of Dawes, which had itself a Piggly Wiggly, a Greyhound station, and lots of other modern conveniences.

That’s where Pontiac was headed, her nine-year-old, four-foot, fifty-five-pound body as agitated as a shaken soda can.

Daddy wouldn’t approve of her speed. “Run too fast at night, cher, and you be sayin bonsoir to the bottom of de quick,” he often warned in his baritone Cajun. That was the sober version. Half a bottle of Everclear into a blitz, his advice got less folksy: “Quicksand, fool!”

Tonight she had no intention of slowing. Besides, quicksand couldn’t snag her so long as she kept to the road. More likely she’d fall into one of the holes Daddy dug himself: Barataria Bay was pitted with his telltale pits, those fruitless attempts at finding the pirate booty Jean Lafitte supposedly hid almost two hundred years ago.

That’s why she’d swung by Doc’s Mercantile beforehand. She’d been saving for the Whiz-Bang fishing rod in the window but had no choice but to blow all she had on a $4.99 flashlight. How else to avoid all ten million of Daddy’s embarrassing holes? Up ahead she could see plenty of other Pointers on their way to Dawes. Like will-o’-the-wisps, their flashlights bobbed.

The fingers of Pontiac’s opposite hand sunk into the humid cover of a book Mr. Peff the librarian joshed was more’n half her size: The Complete Cthulhu Mythos Tales by H. P. Lovecraft.

Like most of the older books in the one-room library, somebody a long while back had carved an octopus symbol into it, this time inside the back cover. Old octopus symbols were all over Alligator Point. On mossed swamp rocks, old tree trunks, the sides of ancient shanties. Pontiac didn’t know why. When she asked Daddy, she didn’t get but an irritated shrug.

Daddy didn’t like not knowing stuff.

Pontiac didn’t either. That’s why she read all the fuck-damn time, to the exasperation of Billy May and the sullenness of Daddy, who glared at her books like they were better men, none of whom needed hooch before facing the day. Mr. Lovecraft, her current choice, designed sentences as serpentine as anything in the swamp. They had rippling scales, dripping fangs.

It lumbered slobberingly into sight, he wrote.

Armed with a book like this, nothing at Bob Fireman’s could spook Pontiac.

This 618-page tome was the only protection she had since her best friend, Billy May, had claimed he was too tired to come to the carny, when the truth was he was too chicken. Pontiac was rip-snorting mad. She and Billy May always went to Bob Fireman’s, on January 8 and June 23 both. Billy always said he could hear the carny’s trucks rumbling all the way from New Orleans.

A fib, naturally. But fibs aren’t quite lies. Fibs are truths stretched taffy-thin to make life more interesting. Bob Fireman’s Wagon Wheel Carnival was a cathedral built to the glory of fibbing. You couldn’t turn your head without bonking into the best fibs you ever saw.

THE WORLD’S SCARIEST RIDE—she doubted that!

$5 TO SEE INDIA’S BIGGEST RAT—try again, suckers!

YOU CAN’T ESCAPE THE MUTANT MAZE—you wanna bet?

That was the trickiest, stickiest part of fibs. Spit them often enough and they piled thick and crusted hard like wasp nests. Daddy said New Orleans was built on “fibs, lies, and fabrications,” the three pillars keeping the city from going glug-glug-glug into the quag. Down here your lungs breathed fibs right along with Bradford pear, Confederate jasmine, Creole mirepoix, and fresh beignets—and the bad stuff too, the flood mold, hot-trash crawfish shells, tourist-buggy horse shit, and Bourbon Street’s hobo funk of liquor, piss, and puke. What didn’t end up in a New Orleanian’s blood ended up filling every pothole in the Quarter—a bubbly black tarn of viscid vice.

Some Pointers called it “nasty-sugar.” It’d get you flying high, yes’m, but it’d gobble your insides too, sure as four dogs have four assholes.

Pontiac splashed through a moat of water spangles and ducked under a spruce-pine bend, and suddenly there was Bob Fireman’s Wagon Wheel. Carousel lights flashed like wet teeth and greasy treats exhaled like hot breath.

Right inside, waiting for her—and her alone—was the Chamber of Dragons. Pontiac’s pores oozed cane sugar. It hurt. She ran her fingertips over the octopus carving in her book and thought about turning tail like Billy May, heading back home.

If things did lumber at Bob Fireman’s, if things did slobber, it was inside the Chamber.

2

A sliver till midnight, Billy heard his name.

“Billy May? Billy May, you in dere?”

He’d been waiting for this call since school let out. On vine-swallowed Alligator Point, where it was hard to tell if your feet were planted in the dry or the damp, where air was water and the skeeters had learned to swim, it was dark enough while the sun was up. When the sun set, round four-thirty this time of year, all things under the Point’s green umbrellas went black.

It had gotten dark during Billy and Pontiac’s walk home. Two-and-a-quarter miles, a narrow dirt track forged by folk who walked, every day, in and out of the Point. There wasn’t no roads. The track dodged opaque pools of stinking sulfur that rose and fell with the Gulf of Mexico tides. There was no telling what was inside—what he and Pontiac had dubbed “hog guzzle,” after the dark slime of mud, grass, chicken shit, and dead vermin in Seth Durber’s hog sty.

Billy had wanted to confess to Pontiac what was spooking him. It was the thing kids whispered about, the thing that drank laughter like Kool-Aid, that chewed good feelings like bubblegum. He’d had a hunch, sure as hunger, or sickness, or needing to pee, that it was coming for him.

The Piper, some folk called it.

But the whole walk home, the Piper didn’t grab Billy’s ankle from inside the coco-yam or drop down from the Spanish moss. Maybe Pontiac’s loud, foul mouth kept it at bay. Getting home safe made Billy feel squat-percent better. That was another thing every kid knew: the Piper made you come to it.

“Billy May,” the voice called. “Don’t you hear me?”

The window sash was up. The skeeter screen was down. The voice needled through it at a child’s pitch. Billy couldn’t tell if he was awake or bad-dreaming. Also, there was the smell of lilacs. Mama didn’t plant no lilacs.

“I ain’t here!” Billy shouted.

Well, shit-balls, that was dumb. Billy cursed himself while the kid-voice chuckled.

Billy backpedaled. “I mean . . . I’m not allowed to come out. Not allowed to do nothin. It’s bedtime. Mama and Daddy’s right in here with me.”

“Dat so?”

“Yup.”

“Ask one of dem to come to de window, so dey can tell you I ain’t nuddin to be afraid of.”

“Who says I’m afraid?”

“Now, Billy May. Anybody wit’ half an ear can tell you afraid. Your little girlfriend could tell. Dat’s why she up and ditched you.”

The thing outside his window knew Pontiac? That scared Billy deep. Unpacking that fear from his chest was like pulling wet leaves from a rubbish bag.

“You go on talking,” Billy said. “I’m not waking up my folks.”

The voice sounded pained. “I’d hate if it got around dat Billy May sleeps in de same room as his folks.”

Lord, there were so many different kinds of fear.

“I don’t,” Billy insisted.

“So your ma and pa, dey not really right dere, are dey?”

The voice’s Cajun was peculiar. Most kids Billy’s age didn’t carry the accent thanks to TV, which flickered to life in these far-flung parts twenty years back.

The skeeter screen shivered. Maybe a breeze. Or maybe the voice was that close.

“Sound to me like you t’ink I’m somet’in bad. Let me ask you dis. How do I know who you are? I can’t see who I’m talkin to eidder!”

Billy lay silent. It was a good point.

“Well, come over here, then,” Billy said. “Look in the window.”

“Ah, my eyesight’s for shit. Can’t see one foot in front of my face.”

“Then how come you’re out at night?” Billy challenged. “Even harder to see in the dark.”

“My old man. Whupped me again. Booted me out. Now, look, I got me a pack of Pall Malls. Stole it out my old man’s Levi’s on de way out. Figured to offer you some.”

“Chuck?” Billy brightened. “Chucky Steve Beatty? That you?”

Now this was different! Billy had smoked Pall Malls three times with Chucky Steve Beatty. It was a good feeling. It was a tough feeling. He wouldn’t mind feeling tough again. Folk might call cigarettes and Big Gulps nasty-sugar, but they sure tasted fine.

Billy swung his legs from the bed. His shin sweat crystallized to ice.

“I’m coming to the window. That’s all.”

“Ain’t askin for nuddin more.”

Pall Malls and a friend, right when Billy needed one. He crossed the floor. Leaned his nose into the skeeter screen. Lilacs like crazy. He panted his hands on the sill, the wood so decayed it barely held the shape of an octopus, carved there long before Billy was even born.

3

Pontiac was her last name. If you called her by her first, she’d warn you that, if you did it a second time, she’d sock you, swear on her mama’s grave. Which she literally did. Each time Daddy survived a real bad bender, he dragged Pontiac to St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery #3 in the city, where he apologized to Janine Pontiac at a tomb so white it made Pontiac’s eyes sting. Daddy always gave Pontiac five minutes alone at the tomb, and damn right she used those minutes to swear. Why the shit did you give me such a punk-ass name, Mama?

Thankfully, most folk on the Point had lost their birth certificates to flood, fire, decay, or disinterest. Oysterman Gregg Bentley went by “Stale Cookies.” Mrs. Burroughs out by Lake Laurier went by “Salazar.” A teenager at the Texaco answered only to “A Walk on the Wild Side.” The Pointers who saw her standing in front of the Chamber of Dragons just said “Hey-hey, Pontiac,” to which she nodded, cool as a Coke.

No one pestered her about Daddy’s whereabouts either. First, they knew he somewhere drunk off his keister. Second, all bayou kids tended to wander. That’s why keeping track, most of all of one another, was a way of life on the Point. Least it used to be. Miss Ward said folk on the Point were in danger of forgetting the lesson of the Battle of New Orleans. We might be as ragtag as Jackson’s army, but in the end, we’re all kin, so we all got to keep track.

That’s why Pontiac carried a third item along with her flashlight and H. P. Lovecraft. Mama had given it to her before she went ahead and croaked from a belly full of cancer. “Keep track of your daddy,” she’d gasped. “Keep track of everything. You got to promise.”

Pontiac had no name for her black-and-white composition notebook besides her “log.” In her log, she logged stuff, like Mama said. Maps of the places she went (she used a hashtag symbol for quicksand) and notes on the things she noticed, like the suspicious blue flowers erupting from the bear-grass by the Deevers’ place, or how Salazar’s dog had been limping for two months now and nobody seemed to give a fuck-damn.

She also kept track of the dead. Not a whole lotta folk were left on Alligator Point. Still somebody managed to kick it every few months. Cancer, mostly. Lots of folk blamed it on the offshore rigs. Some toxic runoff, oil in the water, who knew? There was so much cancer on the Point, Pontiac figured if she snorkeled under the bogs with her flashlight, she’d find mounds of it, rubbery black blobs, quivering as it connived ways to crawl up folk’s drainpipes.

Made sense the carnival kept rolling down to the damp. Carnival, Miss Ward once said, came from carne vale, or “farewell to the flesh.”

In other words, cancer.

Pontiac slid her log out from the back of her jeans. It was warped from sweat and shaped like her lower back. A pencil gored from her gnawing dangled from a string taped to the cover. Taking notes made her feel nearly five feet tall and one hundred pounds powerful.

That’s the boost she needed to take on the Chamber of Dragons.

Three years now Pontiac and Billy May had stood slack-jawed in front of it, cinnamon king cakes forgotten as they listened for the sandpapering of the snakes inside. She’d show Billy May. She’d go in alone and take detailed notes in her log to prove she’d done it.

She walked up to the ticket-seller while scribbling down observations.

Bob Fireman’s carnies wore masks. Not the chicken-feather, sequin-glued, polyester bullshits of Decatur Street tourists either. These masks looked excavated from cobwebby old trunks. Real hair, red velvet hoods, curved balsa-wood beaks, crumbling cloth. The man hunched on the stool outside the Chamber of Dragons wore a lumpy red papier-mâché mask with black horns, hollow eyes, and a little round mouth.

“Five bucks,” the demon said from the white-circled hole.

“Shh,” Pontiac replied. “I’m writing.”

“What’s so important you got to write it?”

“Details.”

The Chamber’s steps were as old as time, and carved into the bottom one was another old octopus symbol.

The demon laughed. Papier-mâché flaked. His croquembouche jowls jiggled.

“Details you’re after? There be details a-plenty inside this truck, pumpkin.”

Pontiac scowled. “I’m nobody’s pumpkin.”

The demon’s red head tilted. His black eyes stared.

“Tell me your name so I might properly say it.”

Daddy had warned it, Miss Ward had warned it: don’t go advertising your name to strangers. Yet Pontiac’s name tickled her tongue like nasty-sugar. She longed to hear it aloud. Hell, she wouldn’t be happy till the whole world heard it.

“Do I know your papa?” the demon probed.

Pontiac doubted it. Most nights Daddy didn’t have the dexterity to get farther than the Pelican, the closest saloon. If this demon met Daddy drinking, he’d know right off Daddy was dying. Not from the kind of cancer that did in Mama, but the kind he nurtured like a pet.

“Or maybe it’s your mama I know,” the demon said.

Pontiac wondered if the demon had been tipped off by her skin color, precisely halfway between Daddy’s white and Mama’s Black. Bringing up her folks was wicked manners either way. Gerard and Janine were quicksand words, capable of drowning the courage Pontiac needed to go inside this truck.

“Pontiac’s the name,” she said in a burst. “And yours?”

“Don’t you know the point of this face-hider? Rich, poor, angel, devil—you wear a mask, you might be any one of them. I could tell you my name. But you’d be a fool to trust it.”

Skunk! She’d been swindled! Heat climbed her cheeks tight as trumpet creeper. She let it. Anger trumped fear any day.

“You going to let me in or not?”

The demon ripped off a ticket. “Guess I don’t know your folks after all. Pontiac, is it? That’s a fine automobile, anyway. I’ll give you a buck off.”

4

It wasn’t Chucky Steve Beatty. But it was a boy, and Billy May liked the looks of him. Mud-smudged cheek and chin. Hair cowlicked stiff. Bare feet clumped with mud large as cougar paws.

“Hey dere, William.”

The boy’s voice slid clarinet-smooth through the racket of frogs, grackles, herons.

“Hey,” Billy replied.

The boy smiled, white teeth gleaming in the jungle dim.

“You’re not wearing glasses,” Billy observed.

“Huh?”

“You said you can’t see good. Why don’t you got glasses?”

“Hell. Guy like me? I’d break ’em, two minutes flat.”

Billy fidgeted. “I don’t believe I know you.”

“You ain’t lookin careful den. I’m at school every day. Well, most days.”

“And you want to . . . share smokes? With me? At midnight?”

“Abraham’s shit. Midnight is de best time for sharin smokes! Ain’t nobody around to go scoldin on you. Not dat I can’t take a scoldin. I took a scoldin so bad once I was bleedin out my butt.”

Billy knew the panic of being outdone. He felt it all the time with Pontiac.

“I’ve been scolded,” he insisted. “A bunch.”

“Dat’s what us bayou boys is alive for, ain’t it?”

“I haven’t heard any other reason.” Billy smiled. “Remind me your name?”

The boy popped a cigarette from the pack, lit it with a Bic’s flick, and took a drag.

“Pierre. T’ough I don’t much care for dat name.”

“Pontiac doesn’t like her real name either.”

“We Cajun types love our masks. Names are masks too.”

Billy May was impressed. “You going to tell me what you go by?”

“Suppose I can’t be shown up by dis Pontiac girl. Mostly I go by de Piper.”

Riding Bob Fireman’s Wombat Scrambler with Pontiac last St. John’s Eve, Billy’s stomach had done a great big lurch right before it sprayed his po’boy lunch. His gut lurched like that now. Then a nice tingly feeling overtook it, like he was already smoking the cigs. Hearing the Piper introduce himself proper made meeting him not as bad as Billy had imagined. The dirty face, messy hair, muddy feet—this kid Pierre looked a lot like him.

Plus, how dangerous was a boy who couldn’t hardly see?

Pierre shook the pack of smokes. Billy never wanted one so bad. He toyed with the skeeter screen’s wayward wires.

“What do they call you the Piper for? You smoke a pipe longside them Pall Malls?”

Pierre grinned. “Pipes are for fancy-pants, which I definitely ain’t. Now rhubarb pie . . . I do enjoy a nice slice of rhubarb pie now and again.” He exhaled a long gray yarn of smoke. “Dat’s a clue, Billy May.”

“Rhubarb,” Billy repeated.

“No, pie, you dumb-dilly.”

“Oh. Pie.” Billy frowned, then lit up. “Miss Ward read us a story about the Pied Piper once. Led a bunch of mice off a cliff.”

“Dat’s de one I mean. But let me ask you dis. If dat ol’ Piper was leadin dem, how come he didn’t walk off de cliff too?”

“I . . . can’t figure it.”

“Because it’s a lie de size of Texas. Just like all dem stories about me.”

The thing in the swamp. Calling folk’s names. Dragging them under the quick. Gobbling their bones. It felt like it’d be downright rude to repeat such rude tales in front of Pierre.

“I ain’t heard no stories,” Billy lied.

“Den how come you won’t come out here?”

“I . . . just don’t want to.”

“First you weren’t allowed to, not you just don’t want to. Abraham’s shit!”

Pierre hurled his cigarette to the ground. Red sparks fanned like switchgrass. He turned and stomped off, and the lilac bouquet went with him. Panic hitched up Billy’s throat like vomit. If he was ever going to keep up with Pontiac, he had to start being braver.

Billy pulled up the skeeter screen, made himself small, rolled over the ancient octopus, and leapt into the weeds below. He got up and sprinted. The swamp was black, blue, and pink, and it curled around Pierre like a mama cat.

“Wait!”

When Pierre turned, he was grinning big, like he’d never doubted Billy was coming.

5

The Chamber of Dragons had nine exhibits, four down each side and one at the end, each illuminated by black lights screwed to the tin hoods of terrariums. Hoods that looked like they could be popped right off by any critter that got gumptious enough. It stank as bad as Daddy coming home from the Pelican: sweat, smoke, and sweet things, but cold and salty too. She didn’t want to smell it; she quit breathing and, right away, got dizzy.

Up front, the Komodo dragon, forked tongue flashing. Next, the Gila monster, as fancifully beaded as a Mardi Gras suit. After that, it got familiar. Baby gators: she’d seen them in the wild, fresh from their eggs, cute if not for their yellow-eyed madness. A thirteen-inch snapping turtle: Daddy once made soup from an eight-incher he caught using sparrow-bait.

Finally, snakes.

Pontiac’s fingertips found the log’s current page by the textures of her handwriting. If it wasn’t so dark, she could keep track, and that would help. Instead, all she could do was wait for another carnival-goer to enter and keep her company. It didn’t happen, and kept not happening. She couldn’t even hear the carnival anymore. She pictured a black hill of cancer flopping out of the marsh and absorbing the whole outfit.

Pontiac wanted to skedaddle.

André Saphir’s voice, calm as ever, slid through her skull.

Any little t’ing can be magic, catin.

Hellfire. If there was anyone Pontiac liked to impress, it was Saphir.

Pontiac stepped up to the first snake. Blacklight irradiated the peeling stickers: PYTHON. The snake was burly, tiger-spotted, twenty feet long, and burnin’ thunderwood. As it moved, its scales created the illusion of going backward, like hubcaps on a speeding car. Pontiac didn’t like it. It was a trick. Same kind the demon ticket-taker tried to pull.

RATTLER next, betraying all laws of physics, diamond-patterned body levitating while its larva-white tail shivered. After that, MAMBA, green as duckweed, lithe as an overlong finger, motionless but for its darting black tongue. After that, CORAL, loose as roadkill guts, its yellow, black, and red stripes bragging how it didn’t even need to hide. Finally, at the end of the truck, the snake Pontiac knew in her heart had been waiting.

Her fear, another scaled thing, broke from its jar and slithered up her throat.

Inside the final tank, sawdust and wood chips.

And something beneath.

It lumbered slobberingly into sight.

Cottonmouths were the bayou’s evilest critters and that was saying a lot. Their worst feature was their lying. Lying, not fibbing. They looked like harmless black snakes except for itty-bitty white marks between their eyes and jaws. Black snakes came at you slow, nothing but curious. Cottonmouths acted just the same. But a quarter of a second was all it took for one to lash out and plunge its fangs.

Here’s what happened next, according to Daddy. Pain like you never knew. Spurting blood. The bite swelling up like bread. Falling down clumsy. Throwing up. Gasping. Going numb. Turning yellow. A cottonmouth bite could end you in five minutes. If Pontiac ever got bit, her fate would hang on a coin toss. Eidder you got de stuff to survive it or you don’t, Daddy said, after which somebody would be obligated to dig a little-girl-sized grave.

The cottonmouth slid from the sawdust, flat head rising, golden eyes locked. Even absent of poison, Pontiac’s blood itched. She thought of Billy May, coward, and André Saphir, hero, and leaned closer. She was brave. The bravest. Her sweaty forehead squeaked against terrarium glass.

6

Most of Alligator Point was “damp”—at sea level or lower. Billy May skirted it, moving through the cool reeds of Chickapee Hollow, halfway to Guimbarde Beach, the site of the old baseball diamond. That’s where Pierre wanted to go. The boy was a born troublemaker, as bold as Pontiac. Even better than Pontiac, he seemed satisfied with himself. Billy didn’t think he’d ever met anyone who felt like that. Life fell on Pointers like a sled of bricks.

But Pierre needed Billy’s perfect eyes. Billy was proud to lead the way.

Unfortunately, Chickapee Hollow cut straight through the hog guzzle.

The dirt track was thin as a bicycle tire and, like anywhere else in the damp, subject to the surprise traps of Gerard Pontiac’s treasure-digging holes. Moist fronds reached out like churchgoers trying to shake hands. Billy pushed them aside only for them to rebound and spank his backside. Some fronds he ripped out only to sense, from the corners of his eyes, replacement fronds springing up.

If Pierre noticed his foibles, he didn’t say, and Billy was grateful. Twice Billy noticed old-ass octopus markings, one scraped into a cow-sized rock and one carved way too high on a water oak, but he didn’t want interrupt Pierre’s chatter. The boy, redolent with lilac now, handed a lit cigarette over Billy’s shoulder. Billy took a drag as fast as he could. It helped with his growing worry. What if Mama woke up and found Billy gone? Worse, what if Daddy did? They’d be mad—though not mad enough to wade through the hog guzzle, not at night.

Smoke curled inside Billy’s lungs, hot as a desert sidewinder. Pall Mall paper sizzled. That’s what he needed to do: burn away the fear, keep talking.

“If the Pied Piper story’s a lie,” Billy asked, “how come you use the name?”

“Assuming I don’t smoke a pipe, you mean.”

Billy laughed. Smoke ribboned past pearly mistletoe into the green-black universe.

“I figure we established that much,” Billy said, relishing the big word in the middle.

“You’re de one who got schooled my story. You tell me.”

Billy pictured Pontiac, scrambly fast except when weighed down with books. Billy thought reading was the pits. Even when the TV fritzed, messing with the rabbit ears was funner than staring at a page of letters. Listening to Miss Ward read, though, that was all right.

“Like I said,” Billy began, “first there was the mice.”

“Abraham’s shit! I’m sick of dem mice!”

“Why you yelling? You told me to tell the story!”

“Get to de part after dat. De part wit’ de children.”

“All right, so the Piper got rid of them mice for the townfolk but when he came to collect his fee, the townfolk said, ‘You didn’t do shit. Just went off playing your flute.’ Piper says, ‘Hey, them mice are gone, ain’t they?’ The townfolk say, ‘Yeah, but they ain’t gone because some stupid flute. We don’t owe you dirt.’ Piper says, ‘My flute music ain’t ordinary music. It’s got magic that makes who hears it follow along.’ The townfolk go, ‘Oh, yeah? If you got that kind of magic, why don’t you blow the flute on us?’ Piper says, ‘I could, but I ain’t going to. If you don’t pay up, I’m going to play my flute at your children. And they’re going to follow along. And they’re going to die, just like them mice.’”

“Rats,” Pierre said. “It was rats.”

Billy stopped and turned toward the boy.

The giant cypresses shivered.

Pierre was wobbling. Billy was surprised. Pierre seemed like the kind of boy who could tight-rope ten miles of fence. But Billy watched Pierre drift into prickly ironweed on one side of the trail before floundering into sticky dixie tick on the other. Billy reached out to steady him, but Pierre caught himself.

Must be his eyesight, Billy thought.

Problem was, Billy no longer saw Pierre’s eyes. Couldn’t see the kid’s face at all. All he could see was the red dot of a cigarette as the boy took a pull.

“It was rats the whole time?” Billy asked. “Why didn’t you say?”

“I will take the story from here,” Pierre replied.

His voice had changed. It was deeper, fussier, how Miss Ward tried to teach them to talk.

“The children followed the Piper’s music,” Pierre continued. “Every single child, right through the sooty, stinking old town, past its bounteous farmland and through valleys cupped inside imperial mountains. Only then, in sight of Earth’s full splendor, did the children walk themselves over a cliff. And all because folk did not pay the Piper.”

Night creature noises filled the silence. Until a delicate pattering joined it: rain, which didn’t make sense. It’d been blue skies all day, dry all night. Billy looked up and saw individual drops catch moonlight like tossed pennies.

Unless he was wrong, the rain only fell on top of the boys.

“I have been done wrong,” Pierre said. “Very wrong.”

Billy’s heart leapt to the pace of the hiccupping toads.

“Not by me, Pierre,” he insisted.

“What did I tell you about that name?”

The lilac scent, so soft and sweet, thickened with rich, gamy rot.

“Piper, I mean.” How stupid Billy had been to open his window to the Piper, to chase after the Piper. That must be how those mice—no, those rats, those children—met their fates. The Piper got them to lead themselves off the cliff.

The rain fell harder. Pierre, the Piper, whatever this thing was, looked up to the hard drops of rain and drank. Billy saw wet teeth, a worming tongue, the gloss of slurping lips.

“No, Billy. You didn’t do anything wrong. But your people did.”

7

The cottonmouth struck.

It did not get its name on accident. The white interior of its mouth had transfixed a millennium of victims. Pontiac, too, in the quarter-second before it bit.

The snake’s fangs clacked against the terrarium, squirting venom down the glass. Pontiac hurled herself backward and tripped. Toward the floor. The dark floor. The extremely dark floor. While she’d been caught in the cottonmouth’s white, the other beasts had escaped. Only now, too late, did she imagine hearing the crackle of splintering glass, the cymbal of tin lids tipped to the floor.

She was halfway fallen when she saw a thing a blacker than the black floor, coiled and waiting.

Odd thoughts in the last seconds before untold fangs bloated her with poison. Church bullshit: snakes in the Garden of Eden. Bayou bullshit: snakes spoken of like they were rainbows in the sky. New Orleans bullshit: the Great Serpent, Li Grand Zombi, skaters of land and water, travelers between realms. The scariest ride, the biggest rat, the mutant maze—she believed all fibs now, for everything had come out of hiding, no more lumbering, no more slobbering.

The coiled thing turned out to be a drain. She saw that when carny lights filled the truck through the open door. Fuck-damn, she thought, as adult hands hoisted her by the armpits and she scrabbled for her log, flashlight, and book. Things never turn out to be what you expect.

In this case, it was the demon dragging her ass, cackling, adding humiliation to the fright. But it wasn’t his bright-red mask burned into her vision. It was the cottonmouth at the instant of attack, so white, so white.

8

The boy-thing, once Pierre, now the Piper, stepped from the rainy shadows. Its pink flesh cracked to pieces. For a moment, its face looked like a dried-out salt flat. Then the shattered bits of boy-skin were sucked into the jelly of the thing’s real face—a dark, eyeless mass.

Hog guzzle, Billy thought as urine scalded his leg.

He was sad about dying. Real sad, real quick. He didn’t think about Mama or Daddy. He thought about Pontiac. Folk always said he and she were two sides of a silver dollar, one light, one dark. By dying he was letting Pontiac down. A silver dollar missing one of it sides wasn’t worth fifty cents. It was worth nothing.

The Piper raised a hand. A boy’s hand, until its fingernails started growing. Not into the pinlike stabbers you get from a testy cat. These were more like seal tusks, thick and yellow, so big they split the fingers like bursting hot dogs. After that, the whole hand tumbled into gristly meat.

Only the thumb stayed normal, and for a reason.

The tusk-fingers sunk holes into Billy’s chest. Billy watched it happen like it was part of the scary movie shown late nights on Channel 3. The thing’s human thumb secured a grip on Billy’s throbbing heart before tearing it free, leathery and spurting, and bringing it to the Piper’s mouth.

It did have a mouth. It was the last thing Billy May saw. The black jelly of its face split open. It was surprising enough to override the wires of pain jammed through Billy’s body. He marveled as the thing ate up his beating heart.

Its mouth, so white, so white.

9

Now and again, Pete Roosevelt was seen apart from Spuds Ulene, but rare were the times Spuds Ulene was seen apart from Pete Roosevelt. Pointers said they were “longside” each other, a word indicating more than togetherness: they were unified in purpose. When the longsiding began, there’d been jibes about queer goings-on. It didn’t last. People respected Pete as a professional, and were impressed by how Spuds, under the older man’s tutelage, had redirected his ill-omened life.

The duo was longside each other in the most common of ways on January 11, except when the backwater track grew too narrow, or pitted with Gerard Pontiac’s infamous pirate-gold holes, and Spuds dropped behind. How Spuds kept up at all was, to Pete, an enduring mystery. Spuds was what Cajuns called a peeshwank: five-foot-zero with the stride to match. Five-foot-two in racing boots, Spuds insisted. Spuds had, in fact, had a short career as a horse jockey. Didn’t like to talk about it much. All he got for three years jockeying was a poorly inserted prosthetic left knee. Pete could identify his limp a mile off, a weird wiggle-skip dance step that kept nearly all weight off his left leg.

Only Spuds’s stream of chatter assured Pete the deputy was keeping up. Pete often interjected a John Wayne quote from Big Jake: “‘You’re short on ears and long on mouth.’” Today, Pete didn’t blame the kid’s nerves. This weren’t a stolen toaster oven—yesterday’s big drama. This was serious business.

“Goll, Pete, you think we’re walking into something bad, don’t you?” Spuds was twenty-seven and evidenced but a smidge of the local accent. Pete was fifty-two and loved the yo-yo-ing Cajun, but having spent his first fifteen years in Texas, it weren’t his to borrow.

“I don’t know,” Pete replied. “You never know.”

“But it sure looks bad, don’t it?”

“Boys run off. Me and you collared our share.”

“Not nine-year-old boys we haven’t. Nine-year-old boys that ain’t shown up in three days. Even I know that’s bad, Pete. What do you figure happened?”

Pete sighed. He had a big chest, and the exhale shook a clump of pondspice.

“Got ill at his ma or pa—both worth gettin ill at, by my recollection. After that, J’connais pas. Hidin out with a buddy, I expect.”

“But his buddy was that girl Pontiac, iddn’t that so?”

“Yeah.”

“And you said you went by the Pontiac place this morning and Pontiac said she ain’t seen him, iddn’t that so?”

“It is.”

“And Pontiac’s not the type to go fibbing to the law, is she? Goll, every time I see that girl, she’s scribbling smart stuff in her little book. She’s the honestest girl you’re bound to meet in the damp, iddn’t that so?”

“That is so.”

Chinaberry leaves shushed against Spuds’s exasperated shrug.

“That only leaves a couple bad endings, Pete, don’t it?”

Sighing this deep in the swamp hurt. Each inhale raised dots of moisture on every bronchiole of the lungs. Hell, maybe Billy May did hightail it through the damp, right past Doc’s Mercantile and over the border into dry-land Dawes. Pete’s understanding was three Pointers had already signed the papers the Oil Man was hawking.

The Oil Man: the only name folk knew him by. Some kind of rep from the offshore oil rigs or coastal refineries. New Year’s Day, the Oil Man had started poking around the Point’s shanties, offering contracts for land that folk had owned since the eighteenth century. Pointers were proud, flagrantly in many cases, of the exciting pirate history behind their shanties. But rumor was the Oil Man’s offer was good. Which didn’t bode well for Alligator Point. Too many more takers and joints that mattered would start shutting down. The store. The school.

Maybe Billy May’s pa had signed. Maybe that’s what upset Billy.

Pete decided to see how well his deputy had gamed it out.

“I’m listenin, Spuds. Tell me those couple of bad endins you’re speculatin.”

“Gator,” Spuds said instantly. “Or bear. Or coyote.”

“Puppy-dogs,” Pete pshawed. “Unless you egg ’em on first.”

“How about a snake? Snakes aren’t puppy-dogs, are they, Pete?”

Points to Spuds, though Pete didn’t think a snake was the culprit. From what he recalled, Billy May weren’t the sort to stray off a trail, not without Pontiac doing the bushwhacking. If Billy had taken a couple snake fangs, his body would have been on a trail, swollen to adult size.

“Not buyin it,” Pete adjudged. “What’s your other bad endin?”

Spuds, still a kid himself, kicked the ground.

“You know what,” he murmured.

Pete did, and he knew why Spuds didn’t want to speak it aloud. The deputy had a paralyzing phobia of quicksand. Some childhood incident, Pete figured, having to do with the monstrous Pa Ulene. Pete wondered if quicksand was the real reason Spuds kept longside him. If Spuds blundered into the quick, he’d have old Pete to pull him out.

“Doggone it,” Pete said. “We ought to be there already.”

“We lost, Pete?” Spuds fretted. His natural cheap-newsprint color went paler.

Always a possibility in the damp, but right then Pete spied a chunk of termite-gnawed wood smothered in burry coastal sandbur. Pete knew tearing up such burrs was a no-no. It ripped them open and scattered more dastardly seed. Pete reached for his Colt .45 to nudge away the plant before remembering he’d had to surrender the sidearm back in ’93 when Bullock Parish went bust, the sheriff department with it.

Gently, he moved aside the sandbur with a pinkie.

Carved deep into the softened wood, barely visible now, was an octopus. Plus four words, three of them misspelled.

MAY’SPRIVUT! KEEP OWT!

“‘We all get off on the wrong trail once in a while,’” Pete said. A quote from The Big Trail, 1930, John Wayne’s first big starring role, a hell of a picture that only tanked because theaters refused to alter their screens for the new 70mm format. The Duke was the one who paid the price, relegated to a decade of Poverty Row flicks until he hit it big with Stagecoach.

John Wayne esoterica kept Pete cool when times got tense.

Spuds tapped the old sign. “Anytime I been to the Mays’ before, right about this spot here is where I got a shotgun pointed at my—”

“Hands to de sky, intruders!”

Pete ducked his big Stetson under a gnarled branch. William May Sr. stood on the gray shambles of his half-sunken porch sixty feet off, a rusty shotgun lodged to his overalled shoulder. Pete waved his hands and smiled as big as he could. One thing he knew about William May Sr. was he was blinder than a decapitated bat.

“Tirez-moi pas, William,” Pete said. “We ain’t intruders.”

“Gat-damn sneakin bandits,” William growled. “First you take my propane. Den you take my air mattress.”

“We ain’t done no such thing, William. This is Pete Roosevelt you’re confabbin with. I helped pull your pirogue off that mudbank two years back. I got with me Spuds Ulene. You know Spuds better’n you know me. Short fella? Funny way of walkin? He helped prop up the west side of your shanty not six months back.”

The shotgun didn’t lower.

“If dat’s you, Spuds, holler out de name I call my wife.”

Pete glanced at Spuds.

“Goll, Pete,” Spuds whispered. “I don’t remember.”

This was worrisome. But Pete took pains to never look worried. He formed a set of wrinkles high on his brow, just like the Duke. John Wayne’s signature expression came off like grim amusement, though in truth, Pete was speculating on how good a shot William May Sr. might be even with headless-bat vision.

“Think harder, Spuds,” Pete whispered. “You think sandburs are sticky, wait’ll you see our brains all over the damp.”

10

Pete Roosevelt and Spuds Ulene met four years prior. August 1, 1994, at Juicy Lucy’s, a grease-sheened twelve-seater burger joint that poured watered-down beer like a spring cloudburst, despite a liquor license that expired the same day that Squeaky Fromme tried to kill President Ford, as Lucy herself like to say. The old broad didn’t sweat it. No ATF hard-ass was gonna tramp this far south into the delta. The joint was damned to keep living, just like Lucy was damned to keep slow-murdering Pointers with the nastiest nasty-sugar around: booze.

Pete ate there a lot. He ate there a lot because he parked there a lot. He might have given his rickety Crown Vicky a nautical name—the Melbourne Queen—but that didn’t mean it could float. Road vehicles got no farther into the Point than the headland. Even four-wheelers were too wide for the trails. Some folk rode horses or mules. A few had airboats. Many had dinghies or canoes. Mostly folk walked, getting to know the terrain through the grip of their bare toes.

The Melbourne Queen was a tank soldered together in late-seventies Motown. A hundred creaks, groans, and pings. Dozens of dents furred with rust. What was left of its chrome accents pitted from gulf-water salt. Not once in all the years Pete had driven the thing had he gotten bodywork or painting done. He liked the idea of keeping the original crests emblazoned on the doors along with the foot-tall lettering: SHERRIF.

Pete had been allowed to keep the car after Bullock Parish went belly-up. Who else would drive the rattletrap?

He’d sheriffed the hell out of the Point for fifteen years. No one was going to forget that. Including Pete. He still thought of himself as holding the office of sheriff. So did the de facto leaders of the Point known as the Saloon Committee, an inebriated syndicate of elders who got liquored up every Tuesday at the Pelican. Most the Point’s forty-seven families stayed liquored up most nights. Well, forty-four since the Oil Man had started handing out contracts.

With the Saloon Committee’s blessing, Pointers kept Pete going. They chipped in for his groceries and gasoline. If Pete missed a cookout, somebody ferreted him a tinfoil-covered tray of the choicest bits. He could get a free cup of joe anywhere, and a free beer at any of his regular haunts—Juicy Lucy’s, Plum Peppers, or the Pelican, where he threw down with the best of them: Pink Zoot, Gully Jimson, Rawley Deevers, and Gerard Pontiac—the patron saint of all local drunkards.

So: Juicy Lucy’s, August 1, 1994. Pete climbed out of the Melbourne Queen, no badge, no .45, pulling on a windbreaker. Eleven years of sheriff weight had made it the only usable remnant of his old uniform—that and the Stetson. He lumbered inside with an inrush of humid air that fluttered several of the tiny, low-grade cotton Jolly Roger flags sold all over the bayou. Pirate’s Pride, the product was called.

Pete shot a hello finger at Lucy behind the bar and took a seat in the darkest booth. Didn’t feel much like socializing. He was having indigestion, and about to fight fire with fire with a grenade of greasy meat.

That’s when he spotted Spuds Ulene. He’d seen the kid before, doing what he was doing now: snorting food like he hadn’t eaten in days. The word kid weren’t real charitable, but Spuds was as small as a kid, with kid mannerisms to boot, scratching at pimples that needed left alone, chewing with mouth agape, slurping electric-yellow soda through a straw. He kept an arm curled around his grub as if a rival gorilla might try to nab it.

Four gorillas had, on cue, loped their way into Juicy Lucy’s, agitating the same little Jolly Rogers. Pete didn’t recognize them, which meant they were jobbers, edging into the swamp to transport equipment, repair a cistern, run a telephone line, something. They didn’t act like they knew one another well, yet had unified as members of a brotherhood. The Brotherhood of Good-Ol’ Normal, forever chartered to rain shit down on anyone they deemed Abnormal.

Pete threw beer after burger and watched the brotherhood’s razzing of Spuds. Pete knew the brotherhood would grow bored pretty quick. Unless Spuds Ulene stood up, planted his feet, and talked back to his tormentors. That shit might work in movies, but in real life, it got your ass kicked.

Because nothing ever went right on the Point, that’s exactly what Spuds did.

Spuds faced them. “The hell y’all over me for? I look funny or something?”

“Yeah,” said a man in an oil-stained Astros cap. “You look real funny.”

“I cleaned up before I came! Checked myself in the mirror! I look fine!”

The brotherhood’s radar wasn’t busted. This Spuds Ulene kid was slow.

Over the next four years, Pete would learn all about Spuds’s capacities—mental, emotional, physical, and, most of all, constitutional. The years Spuds spent as a jockey remained fuzzy as a baby possum, but Pete dug up Spuds’s birth certificate from Holy Charity at St. Beatrice Hospital, filled out by a Sister Parissima. Along with a birth name so heartbreakingly fancified Pete made himself forget it, the words mentally deficient had been added in the notes area.

Spuds’s ma had died from placental abruption. Spuds lived but had been damaged by a lack of umbilical air. His illiterate pa beat the daft boy for sixteen years before dragging him to the Army recruiting office in Dawes. During Spuds’s few weeks in the Army, his C.O. could find no use for him besides kitchen patrol, where Spuds earned his nickname. Far as Pete could tell, that was all Spuds came away with when he was discharged with a familiar curse on his record: mentally deficient.

Pete deduced the broad strokes at Juicy Lucy’s, where the calculus of fairness was changing fast.

“You thought you looked fine?” Astro continued. “Guess you didn’t see it then.”

“See what?” Spuds demanded.

“That shit all over you. That yellow shit.”

“You calling me yellow?”

“Naw. I’m just saying you got yellow shit all over you. This here yellow shit.”