2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BookRix

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

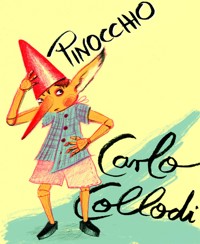

Pinocchio is a novel for children by Italian author Carlo Collodi, written in Florence. It is about the mischievous adventures of Pinocchio (pronounced in Italian), an animated marionette; and his father, a poor woodcarver named Geppetto. Pinocchio is a puppet made from a piece of wood that curiously could talk even before being carved. A wooden-head he starts and a wooden-head he stays - until after years of misadventures caused by his laziness and failure to keep promises he finally learns to care about his family - and then he becomes a real boy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Pinocchio

BookRix GmbH & Co. KG81371 MunichPinocchio

By Carlo Collodi

CHAPTER 1

How it happened that Mastro Cherry, carpenter, found a piece of wood that wept and laughed like a child.

Centuries ago there lived—

"A king!" my little readers will say immediately.

No, children, you are mistaken. Once upon a time there was a piece of wood. It was not an expensive piece of wood. Far from it. Just a common block of firewood, one of those thick, solid logs that are put on the fire in winter to make cold rooms cozy and warm.

I do not know how this really happened, yet the fact remains that one fine day this piece of wood found itself in the shop of an old carpenter. His real name was Mastro Antonio, but everyone called him Mastro Cherry, for the tip of his nose was so round and red and shiny that it looked like a ripe cherry.

As soon as he saw that piece of wood, Mastro Cherry was filled with joy. Rubbing his hands together happily, he mumbled half to himself:

"This has come in the nick of time. I shall use it to make the leg of a table."

He grasped the hatchet quickly to peel off the bark and shape the wood. But as he was about to give it the first blow, he stood still with arm uplifted, for he had heard a wee, little voice say in a beseeching tone: "Please be careful! Do not hit me so hard!"

What a look of surprise shone on Mastro Cherry's face! His funny face became still funnier.

He turned frightened eyes about the room to find out where that wee, little voice had come from and he saw no one! He looked under the bench—no one! He peeped inside the closet—no one! He searched among the shavings—no one! He opened the door to look up and down the street—and still no one!

"Oh, I see!" he then said, laughing and scratching his Wig. "It can easily be seen that I only thought I heard the tiny voice say the words! Well, well—to work once more."

He struck a most solemn blow upon the piece of wood.

"Oh, oh! You hurt!" cried the same far-away little voice.

Mastro Cherry grew dumb, his eyes popped out of his head, his mouth opened wide, and his tongue hung down on his chin.

As soon as he regained the use of his senses, he said, trembling and stuttering from fright:

"Where did that voice come from, when there is no one around? Might it be that this piece of wood has learned to weep and cry like a child? I can hardly believe it. Here it is—a piece of common firewood, good only to burn in the stove, the same as any other. Yet—might someone be hidden in it? If so, the worse for him. I'll fix him!"

With these words, he grabbed the log with both hands and started to knock it about unmercifully. He threw it to the floor, against the walls of the room, and even up to the ceiling.

He listened for the tiny voice to moan and cry. He waited two minutes—nothing; five minutes—nothing; ten minutes—nothing.

"Oh, I see," he said, trying bravely to laugh and ruffling up his wig with his hand. "It can easily be seen I only imagined I heard the tiny voice! Well, well—to work once more!"

The poor fellow was scared half to death, so he tried to sing a gay song in order to gain courage.

He set aside the hatchet and picked up the plane to make the wood smooth and even, but as he drew it to and fro, he heard the same tiny voice. This time it giggled as it spoke:

"Stop it! Oh, stop it! Ha, ha, ha! You tickle my stomach."

This time poor Mastro Cherry fell as if shot. When he opened his eyes, he found himself sitting on the floor.

CHAPTER 2

Mastro Cherry gives the piece of wood to his friend Geppetto, who takes it to make himself a Marionette that will dance, fence, and turn somersaults.

In that very instant, a loud knock sounded on the door. "Come in," said the carpenter, not having an atom of strength left with which to stand up.

At the words, the door opened and a dapper little old man came in. His name was Geppetto, but to the boys of the neighborhood he was Polendina,* on account of the wig he always wore which was just the color of yellow corn.

* Cornmeal mush

Geppetto had a very bad temper. Woe to the one who called him Polendina! He became as wild as a beast and no one could soothe him.

"Good day, Mastro Antonio," said Geppetto. "What are you doing on the floor?"

"I am teaching the ants their A B C's."

"Good luck to you!"

"What brought you here, friend Geppetto?"

"My legs. And it may flatter you to know, Mastro Antonio, that I have come to you to beg for a favor."

"Here I am, at your service," answered the carpenter, raising himself on to his knees.

"This morning a fine idea came to me."

"Let's hear it."

"I thought of making myself a beautiful wooden Marionette. It must be wonderful, one that will be able to dance, fence, and turn somersaults. With it I intend to go around the world, to earn my crust of bread and cup of wine. What do you think of it?"

"Bravo, Polendina!" cried the same tiny voice which came from no one knew where.

On hearing himself called Polendina, Mastro Geppetto turned the color of a red pepper and, facing the carpenter, said to him angrily:

"Why do you insult me?"

"Who is insulting you?"

"You called me Polendina."

"I did not."

"I suppose you think I did! Yet I KNOW it was you."

"No!"

"Yes!"

"No!"

"Yes!"

And growing angrier each moment, they went from words to blows, and finally began to scratch and bite and slap each other.

When the fight was over, Mastro Antonio had Geppetto's yellow wig in his hands and Geppetto found the carpenter's curly wig in his mouth.

"Give me back my wig!" shouted Mastro Antonio in a surly voice.

"You return mine and we'll be friends."

The two little old men, each with his own wig back on his own head, shook hands and swore to be good friends for the rest of their lives.

"Well then, Mastro Geppetto," said the carpenter, to show he bore him no ill will, "what is it you want?"

"I want a piece of wood to make a Marionette. Will you give it to me?"

Mastro Antonio, very glad indeed, went immediately to his bench to get the piece of wood which had frightened him so much. But as he was about to give it to his friend, with a violent jerk it slipped out of his hands and hit against poor Geppetto's thin legs.

"Ah! Is this the gentle way, Mastro Antonio, in which you make your gifts? You have made me almost lame!"

"I swear to you I did not do it!"

"It was I, of course!"

"It's the fault of this piece of wood."

"You're right; but remember you were the one to throw it at my legs."

"I did not throw it!"

"Liar!"

"Geppetto, do not insult me or I shall call you Polendina."

"Idiot."

"Polendina!"

"Donkey!"

"Polendina!"

"Ugly monkey!"

"Polendina!"

On hearing himself called Polendina for the third time, Geppetto lost his head with rage and threw himself upon the carpenter. Then and there they gave each other a sound thrashing.

CHAPTER 3

As soon as he gets home, Geppetto fashions the Marionette and calls it Pinocchio. The first pranks of the Marionette.

Little as Geppetto's house was, it was neat and comfortable. It was a small room on the ground floor, with a tiny window under the stairway. The furniture could not have been much simpler: a very old chair, a rickety old bed, and a tumble-down table. A fireplace full of burning logs was painted on the wall opposite the door. Over the fire, there was painted a pot full of something which kept boiling happily away and sending up clouds of what looked like real steam.

As soon as he reached home, Geppetto took his tools and began to cut and shape the wood into a Marionette.

"What shall I call him?" he said to himself. "I think I'll call him PINOCCHIO. This name will make his fortune. I knew a whole family of Pinocchi once—Pinocchio the father, Pinocchia the mother, and Pinocchi the children—and they were all lucky. The richest of them begged for his living."

After choosing the name for his Marionette, Geppetto set seriously to work to make the hair, the forehead, the eyes. Fancy his surprise when he noticed that these eyes moved and then stared fixedly at him. Geppetto, seeing this, felt insulted and said in a grieved tone:

"Ugly wooden eyes, why do you stare so?"

There was no answer.

After the eyes, Geppetto made the nose, which began to stretch as soon as finished. It stretched and stretched and stretched till it became so long, it seemed endless.

Poor Geppetto kept cutting it and cutting it, but the more he cut, the longer grew that impertinent nose. In despair he let it alone.

Next he made the mouth.

No sooner was it finished than it began to laugh and poke fun at him.

"Stop laughing!" said Geppetto angrily; but he might as well have spoken to the wall.

"Stop laughing, I say!" he roared in a voice of thunder.

The mouth stopped laughing, but it stuck out a long tongue.

Not wishing to start an argument, Geppetto made believe he saw nothing and went on with his work. After the mouth, he made the chin, then the neck, the shoulders, the stomach, the arms, and the hands.

As he was about to put the last touches on the finger tips, Geppetto felt his wig being pulled off. He glanced up and what did he see? His yellow wig was in the Marionette's hand. "Pinocchio, give me my wig!"

But instead of giving it back, Pinocchio put it on his own head, which was half swallowed up in it.

At that unexpected trick, Geppetto became very sad and downcast, more so than he had ever been before.

"Pinocchio, you wicked boy!" he cried out. "You are not yet finished, and you start out by being impudent to your poor old father. Very bad, my son, very bad!"

And he wiped away a tear.

The legs and feet still had to be made. As soon as they were done, Geppetto felt a sharp kick on the tip of his nose.

"I deserve it!" he said to himself. "I should have thought of this before I made him. Now it's too late!"

He took hold of the Marionette under the arms and put him on the floor to teach him to walk.

Pinocchio's legs were so stiff that he could not move them, and Geppetto held his hand and showed him how to put out one foot after the other.

When his legs were limbered up, Pinocchio started walking by himself and ran all around the room. He came to the open door, and with one leap he was out into the street. Away he flew!

Poor Geppetto ran after him but was unable to catch him, for Pinocchio ran in leaps and bounds, his two wooden feet, as they beat on the stones of the street, making as much noise as twenty peasants in wooden shoes.

"Catch him! Catch him!" Geppetto kept shouting. But the people in the street, seeing a wooden Marionette running like the wind, stood still to stare and to laugh until they cried.

At last, by sheer luck, a Carabineer* happened along, who, hearing all that noise, thought that it might be a runaway colt, and stood bravely in the middle of the street, with legs wide apart, firmly resolved to stop it and prevent any trouble.

* A military policeman

Pinocchio saw the Carabineer from afar and tried his best to escape between the legs of the big fellow, but without success.

The Carabineer grabbed him by the nose (it was an extremely long one and seemed made on purpose for that very thing) and returned him to Mastro Geppetto.

The little old man wanted to pull Pinocchio's ears. Think how he felt when, upon searching for them, he discovered that he had forgotten to make them!

All he could do was to seize Pinocchio by the back of the neck and take him home. As he was doing so, he shook him two or three times and said to him angrily:

"We're going home now. When we get home, then we'll settle this matter!"

Pinocchio, on hearing this, threw himself on the ground and refused to take another step. One person after another gathered around the two.

Some said one thing, some another.

"Poor Marionette," called out a man. "I am not surprised he doesn't want to go home. Geppetto, no doubt, will beat him unmercifully, he is so mean and cruel!"

"Geppetto looks like a good man," added another, "but with boys he's a real tyrant. If we leave that poor Marionette in his hands he may tear him to pieces!"

They said so much that, finally, the Carabineer ended matters by setting Pinocchio at liberty and dragging Geppetto to prison. The poor old fellow did not know how to defend himself, but wept and wailed like a child and said between his sobs:

"Ungrateful boy! To think I tried so hard to make you a well-behaved Marionette! I deserve it, however! I should have given the matter more thought."

CHAPTER 4

The story of Pinocchio and the Talking Cricket, in which one sees that bad children do not like to be corrected by those who know more than they do.

Very little time did it take to get poor old Geppetto to prison. In the meantime that rascal, Pinocchio, free now from the clutches of the Carabineer, was running wildly across fields and meadows, taking one short cut after another toward home. In his wild flight, he leaped over brambles and bushes, and across brooks and ponds, as if he were a goat or a hare chased by hounds.

On reaching home, he found the house door half open. He slipped into the room, locked the door, and threw himself on the floor, happy at his escape.

But his happiness lasted only a short time, for just then he heard someone saying:

"Cri-cri-cri!"

"Who is calling me?" asked Pinocchio, greatly frightened.

"I am!"

Pinocchio turned and saw a large cricket crawling slowly up the wall.

"Tell me, Cricket, who are you?"

"I am the Talking Cricket and I have been living in this room for more than one hundred years."

"Today, however, this room is mine," said the Marionette, "and if you wish to do me a favor, get out now, and don't turn around even once."

"I refuse to leave this spot," answered the Cricket, "until I have told you a great truth."

"Tell it, then, and hurry."

"Woe to boys who refuse to obey their parents and run away from home! They will never be happy in this world, and when they are older they will be very sorry for it."

"Sing on, Cricket mine, as you please. What I know is, that tomorrow, at dawn, I leave this place forever. If I stay here the same thing will happen to me which happens to all other boys and girls. They are sent to school, and whether they want to or not, they must study. As for me, let me tell you, I hate to study! It's much more fun, I think, to chase after butterflies, climb trees, and steal birds' nests."

"Poor little silly! Don't you know that if you go on like that, you will grow into a perfect donkey and that you'll be the laughingstock of everyone?"

"Keep still, you ugly Cricket!" cried Pinocchio.

But the Cricket, who was a wise old philosopher, instead of being offended at Pinocchio's impudence, continued in the same tone:

"If you do not like going to school, why don't you at least learn a trade, so that you can earn an honest living?"

"Shall I tell you something?" asked Pinocchio, who was beginning to lose patience. "Of all the trades in the world, there is only one that really suits me."

"And what can that be?"

"That of eating, drinking, sleeping, playing, and wandering around from morning till night."

"Let me tell you, for your own good, Pinocchio," said the Talking Cricket in his calm voice, "that those who follow that trade always end up in the hospital or in prison."

"Careful, ugly Cricket! If you make me angry, you'll be sorry!"

"Poor Pinocchio, I am sorry for you."

"Why?"

"Because you are a Marionette and, what is much worse, you have a wooden head."

At these last words, Pinocchio jumped up in a fury, took a hammer from the bench, and threw it with all his strength at the Talking Cricket.

Perhaps he did not think he would strike it. But, sad to relate, my dear children, he did hit the Cricket, straight on its head.