9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

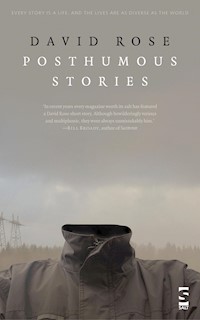

David Rose's debut novel Vault won high praise upon its publication in 2011. Now, Salt is pleased to present Rose's long-awaited collection of short stories – a series of captivating tales that showcase his exceptional talent as a writer. Rose has always been best-known as a master of the short story, and his work has featured in several magazines and anthologies. Posthumous Stories, written over the past twenty-five years, turns a sharply-focussed lens on an extraordinary range of lives: from a road crew installing speed humps, a divorced man living rough, and a childless children's entertainer, to the son of a famous artist, the dedicatee of a violin concerto, and an honorary member of the Beatles. Also included here are 'Private View', the author's first published story in Literary Review and 'Tragos', a mesmerising tale based on the Raoul Moat case. The wonder of this collection lies in its elegance; Rose's prose, described by the Guardian as "sinewy and spare" is astounding; perfectly crafted. His stories unfurl with an uncanny ability to fix themselves in the memory – crisp, succinct and finely wrought. These are vignettes of remarkable potency; subtle, tantalising and unexpected, which will stay with you long after the last page is turned.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Posthumous Stories

David Rose’s debut novel Vault won high praise upon its publication in 2011. Now, Salt is pleased to present Rose’s long-awaited collection of short stories – a series of captivating tales that showcase his exceptional talent as a writer.

Rose has always been best-known as a master of the short story, and his work has featured in several magazines and anthologies. Posthumous Stories, written over the past twenty-five years, turns a sharply-focussed lens on an extraordinary range of lives: from a road crew installing speed humps, a divorced man living rough, and a childless children’s entertainer, to the son of a famous artist, the dedicatee of a violin concerto, and an honorary member of the Beatles. Also included here are ‘Private View’, the author’s first published story in Literary Review and ‘Tragos’, a mesmerising tale based on the Raoul Moat case.

The wonder of this collection lies in its elegance; Rose’s prose, described by the Guardian as “sinewy and spare” is astounding; perfectly crafted. His stories unfurl with an uncanny ability to fix themselves in the memory – crisp, succinct and finely wrought. These are vignettes of remarkable potency; subtle, tantalising and unexpected, which will stay with you long after the last page is turned.

Praise for David Rose

‘In recent years every magazine worth its salt has featured a David Rose short story. Although bewilderingly various and multiphonic they were always unmistakably him . . . Now comes Vault, a strange, spare tale of army snipers, nuclear espionage and competition cycling. The Tour de France features but this is closer to Flann O’Brien or Alfred Jarry than Lance Armstrong, with its shifting narrators continually mutinying against their creator – Rose, God or themselves. Although it has the drive of a Len Deighton thriller it also contrives to be simultaneously playful and tragic, giddily comic and heartbreakingly sad, making one suspect that there are no limits to what this writer may do.’ —Bill Broady, author of The Swimmer (Flamingo, 2000)

Posthumous Stories

David Rose was born in 1949, living outside West London, between Windsor and Richmond. He spent his working life in the Post Office. His debut story was published in The Literary Review, and since then he has been widely published by small presses in the UK and Canada. He was joint owner and Fiction Editor of Main Street Journal.

Also by David Rose

Vault (Salt, 2011)

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © David Rose, 2013

The right of David Rose to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2013

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 1 84471 983 9 electronic

This collection is dedicated to the editors of literary magazines everywhere – the unsung heroes of the literary world – and to one hero in particular: Nick Royle.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Afterword

Posthumous Stories

Dedication

A Nice Bucket

Private View

Flora

The Fall

The Fifth Beatle

Viyborg

Clean

Rectilinear

In Evening Soft Light

Shuffle

Lector

Tragos

Zimmerman

Home

The Castle

Acknowledgements

‘Dedication’ © 2013 by David Rose, originally published in Beat the Dust (online)

‘A Nice Bucket’ © 2001 by David Rose, originally published in Stripe (Black Bile Press)

‘Private View’ © 1989 by David Rose, originally published in Literary Review January 1989

‘Flora’ © 2010 by David Rose, originally published in London Magazine April/May 2010

‘The Fall’ © 2013 by David Rose, original to this collection

‘The Fifth Beatle’ © 2002 by David Rose, originally published in The Rue Bella #8

‘Viyborg – A Novel’ © 2009 by David Rose, originally published in The Warwick Review June 2009

‘Clean’ © 1998 by David Rose, originally published in Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing (Quartet) ed Nicholas Royle

‘Rectilinear’ © 2013 by David Rose, originally published in Terrain (online)

‘In Evening Soft Light’ © 2002 by David Rose, originally published in The Rue Bella #9

‘Shuffle’ © 2010 by David Rose, originally published in The Loose Canon #2

‘Lector’ © 2008 by David Rose, originally published in Brace (Comma Press) ed Jim Hinks

‘Tragos’ © 2012 by David Rose, originally published in Bicycle Review (online)

‘Zimmerman’ © 1997 by David Rose, originally published in Iron #81/82

‘Home’ © 2004 by David Rose, originally published in Zembla #4

‘The Castle’ © 2013 by David Rose, original to this collection

The author wishes to thank the editors of the magazines and anthologies in which stories first appeared.

Afterword

A note on the composition of ‘The Castle’ and ‘The Fall’ might be in order.

Astute readers may find that the opening sentence/s of each of my chapters of ‘The Castle’ seem familiar. They are in fact taken from Kafka’s novel of the same name. That was deliberate, and this is why:

Walking round Windsor and past the Castle, while casting round for a subject for a first attempt at a novel, I had the idea of basing it on the fire, and subsequent restoration which was then nearing completion. I would, I thought, call it simply The Castle.

That would obviously prompt comparisons with Kafka, though. Why not, then, since I was in need of a plot, or at least a plot generator, turn that to my advantage? Why not useOuLiPianprocedures and structure my castle on Kafka’s, build mine on his foundations?

The procedure was simple. Predetermined sentences from Kafka would be the opening sentences of mine, providing me with a scaffold at least. Thus taking the corresponding sentence of each chapter of Kafka, e.g. the fifth sentence of chapter five, would give me the opening sentence of my chapter five. No cheating. Except once, or rather twice: the first two sentences of Kafka I used together, then the second two. There are therefore no chapters 2 or 4 in my Castle. But no further cheating.

This strict adherence led to an uncanny discovery. One of Kafka’s sentences referred to the character ‘Brunswick’; very well, I would, when the time came, invent a similar character, my own Brunswick. No need: I discovered in researching the fire that one tower alone suffered such extensive damage as to be irreparable. It was the Brunswick Tower. Fate or the writing gods seemed to approve my project.

Whether readers will also is for them to say.

I should add that the editor is fully absolved of any solecism resulting from the composition methods and style.

‘The Fall’ was written in the late 1990s. I point this out not only to explain seeming anachronisms (e.g. reference to Railtrack) but also to pre-empt accusations of plagiarism of the recent scaling of the Shard by Greenpeace activists – an exploit I greatly admired.

‘The Fall’ was also composed using a rudimentary OuLiPian constraint, a constraint I have since used on a greater scale: a series of puns, the second meaning of which propels the plot of the following chapter, e.g. ‘rift’, ‘glib’, and of course the title, with its autumnal shades and echoes of Camus. The structural technique was entirely for my benefit, and intentionally concealed; spotting it adds little, I suspect, to the reader’s meagre enjoyment of the story.

Posthumous Stories

Dedication

. . . in 1938 but not discovered until after his death in 1953. It was first performed in 1954 at the Edinburgh Festival, and was later taken into the repertoire of many leading violinists. The work was dedicated, cryptically, ‘to Stevie’, whose parents, it transpired, had befriended him soon after his arrival in England, and in whose house he spent much of his time until the War.

For this centenary concert, we have tracked down, and have in the studio, the dedicatee, who will give us a more personal view of this once controversial work.

Before we discuss the work in detail, a general question: how did it feel to have had such a work dedicated to you?

– Not an easy question. I suppose that . . . one would have to say, at the risk of sounding ungrateful, that . . . as far as one was aware of it, it rather blighted one’s life. Such a lot to live up to.

– Was it ever performed in his lifetime, informally perhaps?

– Only by himself, twice. He refused to play any of it until it was finished. Then he played it to me, at least the solo part, in the guest room, with me perched on the bed, candlewick tickling, trying to look receptive. Then a proper performance at a little get-together of my parents’, my mother playing the piano reduction.

– You never attempted to play it yourself?

– Me? Good heavens, my dear, I don’t play. I’m entirely unmusical. That was the joke, you see. Born tone-deaf. Broke my parents’ hearts, but there it was.

– Did he ever discuss the work with you?

– Not technically. I wouldn’t have understood, would I? And I was only eight or so at the time. But I would sometimes be aware of him watching me romping with the dog, something of that sort, and he’d say, I’ll put that in, Stevie. Always called me Stevie. No one else did. I must say I found being observed rather disconcerting.

– But in the long run, just the opposite?

– Oh, why didn’t I say that?

– The work is a rhapsodic two-movement work, very similar to the Bartók first violin concerto, which was also a posthumously performed work, and dedicated to Steffi Geyer. The similarities are, in fact, uncanny. Did he use the Bartók as a model?

– I couldn’t say. Bartók was one of the names that kept bobbing around above my head in those days. I think he admired Bartók, but as to conscious influence . . .

– One of the stylistic, indeed structural, features of the work is a continually arrested development, a feature peculiar in that period, to this work. Did he give any indication of compositional difficulty at the time? He was normally a fluent composer.

– I do remember him once saying to me – it was a very hot August day, I’d been swimming in the river, he’d sat on the bank and I’d flopped down beside him, puffed out and dripping, and he was whistling a little tune, and he stopped and looked down at me and said, If I develop this theme any further, Stevie, I’ll be arrested. And he laughed.

– Could that have been the Austrian ländler in the second movement, bearing in mind that this was in 1938, just after the Anschluss . . .

– It could have been. I didn’t pay much attention at the . . .

– That ländler becomes in fact the main theme of the coda, drawing all the other fragmentary themes into it until they finally build into the closing eleven-note chord . . .

– And he was right. Because eventually, of course, he was arrested, wasn’t he?

– He was interned, certainly, at the outbreak of the War, the duration of which he spent on the Isle of Wight, I understand?

– He would have seen it as being arrested. So did we.

– Your family?

– My friends. At school. I was taunted with it. Fritz–lover, that sort of thing.

– Was that the beginning of the blight you talked about?

– A foretaste, I suppose. They were . . . lonely years. But . . . one recovers, presses on.

– Could you say a little more of how it affected you later? You weren’t flattered by it?

– At the time I didn’t realise how famous he was. And the work itself, let alone the dedication, simply wasn’t known. When it was, later, I suppose, yes, one would have to own up to a certain pride. By that time I was working in music publishing, the only musical activity I was remotely fitted for – the typewriter being the only instrument I ever mastered – and I had the contacts, of course. And yes, it did rather enhance one’s standing, quite usefully.

– Did you publish his work?

– No, he had always been with Schott. But, as I say, it proved useful. At a cost.

– ?

– Assumptions were made, perhaps, or so I felt, although I was maybe oversensitive. And it brought back the feeling . . . of having let people down. Disappointed people. My parents first, then him. I remembered the relief I had felt when no more was heard of the work after its performance.

– His performance?

– Yes. And when it suddenly popped up after the accident . . .

– His suicide?

– Yes, somehow one felt . . . implicated. One felt . . . silly, of course – a bond, like that between murderer and victim.

– But that was fifteen years later. And the War in between. Did he remain in touch during the War?

– I don’t suppose communication was allowed.

– But he renewed contact after the War?

– There were visits. But it wasn’t the same. He wasn’t the same. There was a strain, a tension.

– When it was first performed publicly, what did you think of it? Was it substantially as you remembered it?

– Well, I hadn’t remembered, not really. I recognised bits of the solo part. But the orchestration makes so much difference, so much more colour, more power. It seemed more . . . wistful than I recollected. Yet strangely also more . . . sinister, I think I would have to say. And shocking, the ending . . .

– The notorious eleven-note chord – notorious at the time, this being before the later Mahler symphonies were known here. Maybe we could discuss it a little. As I said earlier, fragmentary themes and motifs are drawn into the main theme until they coalesce in an eleven-note chord in the orchestra, the full twelve-note chord being completed by the solo violin’s B natural, or as the Germans refer to it, H. The chord is held, then the orchestra dies away, leaving the violin’s B exposed, becoming fortissimo, at which point the orchestra repeats its chord, only to fade again, leaving the violin’s still fortissimo B, which then falls to B flat before the violin too dies into silence. Was this as shocking as you had remembered it?

– I had only remembered the crash of the last chord and my mother’s curses at trying to play it. The lone note I didn’t recall, or its repetition.

– He added that later?

– I think, probably . . .

– B – B flat, in German notation, H – B. His initials. Clearly a self–reference. Commentators have noted the defiance in that, in the finale as a whole. But whether it was a defiance of his German-Viennese past, or a defiant reacceptance of it – he’d used the serial method earlier in his career – is not clear. Can you shed light on that?

– I can only say that I had the impression later, after the War, that he had felt doubly betrayed. He had made great efforts to become English – wore tweed suits, mainly secondhand, some of them my father’s, always carried an umbrella, took to saying ‘bloody’ a lot because he thought that very English, and very funny, incidentally.

– It’s very noticeable that all his wartime and post-war works, all unperformed in his lifetime, were again to German texts or had German titles – the Five Children’s Songs of Brecht, the Heine Lieder, the orchestral Kinderszenen. And again the preoccupation with children, which runs through his work from 1935 onwards, his arrival in England.

– True. He spoke to me once of his Rupert Lieder, I remember.

– Rückert Lieder?

– No. He had an idea for setting the Rupert Bear strip cartoons as a sung ballet. He’d been entranced by the annuals. I had a check scarf at the time – he bought it for me, I now remember – but whether the scarf or the idea came first I don’t know. I remember him playing me the ‘Rupert theme’.

– Did he ever complete them?

– I heard nothing more of them. And soon after, he started work on the Lewis Carroll songs.

– Why the preoccupation with childhood, do you suppose?

– I really couldn’t . . . I can’t say . . . I remember him, though, sitting at my mother’s piano, picking out tunes which he would then play again backwards, and he’d say to me, If only we could turn the clock back, Stevie. Curiously, I learned, much later from my father – we were arguing about Freud, my father was an admirer – of an idea he, Hans, Uncle Hans, had had for a revised version – this was some time after the War – for his Freud oratorio . . .

– The early expressionist settings from Studies in Hysteria, the ‘Freudetraüme’?

– Yes, which was to have some of the vocal parts performed on a tape recording, so they could be played backwards. He maintained that Freud always got things back to front, so it would be putting him to rights . . .

– Fascinating. But unfortunately time doesn’t reverse itself even for the BBC, and my earphone is telling me that the orchestra is now assembled on the platform, the conductor is about to enter – yes he’s mounting the rostrum. So, we are about to hear now the Violin Concerto, opus posthumous, by Hans Bahr, played in this centenary concert by the acclaimed young Swiss violinist . . .

Mother’s soft chords but on woodwind now dark now the violin should yes long hushed trill now the octave leaps upward up up with the lark Stevie already working in the summerhouse no sleep for the wicked coffee with figs ordered specially toast no butter honey only while I ruled the paper stave pen dipped ink over my knees into the garden whistling forgetting me birdsong jotted in his notebook England a nest of songbirds, Stevie asking me names birds flowers but I couldn’t blade of couch grass between his fingers hollowed his hands blowing a trill there now on the oboe but too soft raucous should be raucous now mock-jaunty motif Molto giocoso, Muriel, molto giocoso bassoon’s sad clowning bent over on his hands head between his knees hat on his bottom Everything topsy turvy, Stevie, isn’t that your English expression? but I couldn’t laugh couldn’t respond climbed once the apple tree pulling me up holding his cheek trunk rough safe but snare rattling tympani quiet now quickening alla marcia all the instruments joining remember here low piano arpeggio yes now on trombones a raspberry Don’t grow up, Stevie.

second movement again trill but faltering fading again again fading slow dance waltz but soft backwards forwards swing hung from the pine needles soft to fall on catching pushing hands on my waist catching and pushing and up up to the blue between higher Not too high, Stevie, you’ll fall like Icarus but still higher high in the treble More treble, Muriel treble betrayal