Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

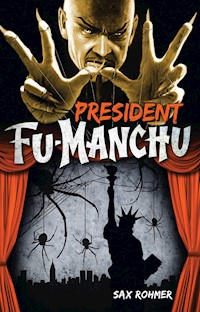

Washington, 1936—on the eve of War, the United States holds a crucial election. The candidate who takes office will grasp the reins of power, while the world teeters on the brink. The fate of mankind will rest with man who controls the White House. "A sterling example of the classic adventure story, full of excitement and intrigue. Fu-Manchu is up there with Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, and Zorro."—Charles Ardai, award-winning novelist and founder of Hard Case Crime THE INVISIBLE PRESIDENT Aided by federal agent Mark Hepburn, Sir Denis Nayland Smith must discover the link between Fu-Manchu and the disappearance of a leading American candidate. Should they fail, the Devil Doctor will move yet another step closer toward his dream of global domination

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 438

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for President Fu-Manchu

Also by Sax Rohmer

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One: The Abbot of Holy Thorn

Chapter Two: A Chinese Head

Chapter Three: Above the Blizzard

Chapter Four: Mrs. Adair

Chapter Five: The Special Train

Chapter Six: At Weaver’s Farm

Chapter Seven: Sleepless Underworld

Chapter Eight: The Black Hat

Chapter Nine: The Seven-Eyed Goddess

Chapter Ten: James Richet

Chapter Eleven: Red Spots

Chapter Twelve: Number 81

Chapter Thirteen: Tangled Clues

Chapter Fourteen: The Scarlet Brides

Chapter Fifteen: The Scarlet Brides (Concluded)

Chapter Sixteen: “Bluebeard”

Chapter Seventeen: The Abbot’s Move

Chapter Eighteen: Mrs. Adair Reappears

Chapter Nineteen: The Chinese Catacombs

Chapter Twenty: The Chinese Catacombs (Concluded)

Chapter Twenty-One: Carnegie Hall

Chapter Twenty-Two: Moya Adair’s Secret

Chapter Twenty-Three: Fu-Manchu’s Water-Gate

Chapter Twenty-Four: Siege of Chinatown

Chapter Twenty-Five: Siege of Chinatown (Concluded)

Chapter Twenty-Six: The Silver Box

Chapter Twenty-Seven: The Stratton Building

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Paul Salvaletti

Chapter Twenty-Nine: A Green Mirage

Chapter Thirty: Plan of Attack

Chapter Thirty-One: Professor Morgenstahl

Chapter Thirty-Two: Below Wu King’s

Chapter Thirty-Three: The Balcony

Chapter Thirty-Four: “The Seven”

Chapter Thirty-Five: The League of Good Americans

Chapter Thirty-Six: The Human Equation

Chapter Thirty-Seven: The Great Physician

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Westward

Chapter Thirty-Nine: The Voice from the Tower

Chapter Forty: “Thunder of Waters”

Appreciating Dr. Fu-Manchu by Leslie S. Klinger

Introduction to “The Blue Monkey” by William Patrick Maynard

Free Sample of The Blue Monkey by Sax Rohmer

“Insidious fun from out of the past. Evil as always, Fu-Manchu reviles as well as thrills us.”

Joe R. Lansdale, recipient of the Horror Writers Association Lifetime Achievement Award

“Without Fu-Manchu we wouldn’t have Dr. No, Doctor Doom or Dr. Evil. Sax Rohmer created the first truly great evil mastermind. Devious, inventive, complex, and fascinating. These novels inspired a century of great thrillers!”

Jonathan Maberry, New York Times bestselling author of Assassin’s Code and Patient Zero

“The true king of the pulp mystery is Sax Rohmer—and the shining ruby in his crown is without a doubt his Fu-Manchu stories.”

James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of The Devil Colony

“Fu-Manchu remains the definitive diabolical mastermind of the 20th century. Though the arch-villain is ‘the Yellow Peril incarnate,’ Rohmer shows an interest in other cultures and allows his protagonist a complex set of motivations and a code of honor which often make him seem a better man than his Western antagonists. At their best, these books are very superior pulp fiction… at their worst, they’re still gruesomely readable.”

Kim Newman, award-winning author of Anno Dracula

“Sax Rohmer is one of the great thriller writers of all time! Rohmer created in Fu-Manchu the model for the super-villains of James Bond, and his hero Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie are worthy stand-ins for Holmes and Watson… though Fu-Manchu makes Professor Moriarty seem an under-achiever.”

Max Allan Collins, New York Times bestselling author of The Road to Perdition

“I grew up reading Sax Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu novels, in cheap paperback editions with appropriately lurid covers. They completely entranced me with their vision of a world constantly simmering with intrigue and wildly overheated ambitions. Even without all the exotic detail supplied by Rohmer’s imagination, I knew full well that world wasn’t the same as the one I lived in… For that alone, I’m grateful for all the hours I spent chasing around with Nayland Smith and his stalwart associates, though really my heart was always on their intimidating opponent’s side.”

K. W. Jeter, acclaimed author of Infernal Devices

“A sterling example of the classic adventure story, full of excitement and intrigue. Fu-Manchu is up there with Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, and Zorro—or more precisely with Professor Moriarty, Captain Nemo, Darth Vader, and Lex Luthor—in the imaginations of generations of readers and moviegoers.”

Charles Ardai, award-winning novelist and founder of Hard Case Crime

“I love Fu-Manchu, the way you can only love the really GREAT villains. Though I read these books years ago he is still with me, living somewhere deep down in my guts, between Professor Moriarty and Dracula, plotting some wonderfully hideous revenge against an unsuspecting mankind.”

Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy

“Fu-Manchu is one of the great villains in pop culture history, insidious and brilliant. Discover him if you dare!”

Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling co-author of Baltimore: The Plague Ships

“Exquisitely detailed… [Sax Rohmer] is a colorful storyteller. It was quite easy to be reading away and suddenly realize that I’d been reading for an hour or more without even noticing. It’s like being taken back to the cold and fog of London streets.”

Entertainment Affairs

“Acknowledged classics of pulp fiction… the bottom line is Fu-Manchu, despite all the huffing and puffing about sinister Oriental wiles and so on, always comes off as the coolest, baddest dude on the block.”

Comic Book Resources

“Undeniably entertaining and fun to read… It’s pure pulp entertainment—awesome, and hilarious and wrong. Read it.”

Shadowlocked

“The perfect read to get your adrenalin going and root for the good guys to conquer a menace that is almost supremely evil. This is a wild ride read and I recommend it highly.”

Vic’s Media Room

THE COMPLETE FU-MANCHU SERIESBY SAX ROHMER

Available now from Titan Books:

THE MYSTERY OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE RETURN OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE HAND OF FU-MANCHU

DAUGHTER OF FU-MANCHU

THE MASK OF FU-MANCHU

THE BRIDE OF FU-MANCHU

THE TRAIL OF FU-MANCHU

Coming soon from Titan Books:

THE DRUMS OF FU-MANCHU

THE ISLAND OF FU-MANCHU

THE SHADOW OF FU-MANCHU

RE-ENTER FU-MANCHU

EMPEROR FU-MANCHU

THE WRATH OF FU-MANCHU

PRESIDENT FU-MANCHUPrint edition ISBN: 9780857686107E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686763

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First published as a novel in the UK by William Collins & Co. Ltd, 1936First published as a novel in the US by Doubleday, Doran, 1936

First Titan Books edition: March 201410 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2014 The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

Frontispiece illustration by C. C. Beall, first appearing in Collier’s Weekly, March 7 1936. Special thanks to Dr. Lawrence Knapp for the illustrations as they appeared on “The Page of Fu-Manchu,” http://www.njedge.net/~knapp/FuFrames.htm

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

The Invisible President

CHAPTER ONE

THE ABBOT OF HOLY THORN

Three cars drew up, the leading car abreast of a great bronze door bearing a design representing the beautiful agonized face of the Savior, a crown of thorns crushed down upon His brow. A man jumped out and ran to this door. Ten men alighted behind him. The wind howled around the tall tower and a carpet of snow was beginning to form upon the ground. Four guards, appearing as if by magic out of white shadows, lined up before the door.

“Stayton!” came sharply. “Stand aside.”

One of the guards stepped forward—peered. A tall, slightly built man who had been in the leading car was the speaker. He had a mass of black, untidy hair, and his face, though that of one not yet west of thirty, was grim and square-jawed. He was immediately recognized.

“All right, Captain.”

The man addressed as captain turned to the party and issued rapid orders in a low tone. The leader, muffled up in a leather, fur-collared topcoat, his face indistinguishable beneath the brim of a soft felt hat already dusted with snow, rang a bell beside the bronze door.

It opened so suddenly that one might have supposed the opener to have been waiting inside for this purpose; a short, elegant young man, almost feminine in the nicety of his attire.

The new arrival stepped in and quickly shut out the storm, closing the bronze door behind him. In a little lobby communicating with a large square room equipped as an up-to-date office, but at this late hour deserted, he stood staring at the person who had admitted him.

A churchlike lamp, hung from a bracket on the wall, now cast its golden light upon the face of the man wearing the leather coat. He had removed his hat, revealing a head of crisp, graying hair. His features were angular to the point of gauntness, and his eyes had the penetrating quality of armored steel, while his complexion seemed strangely out of keeping with the climate, being sun-baked to a sort of coffee color.

“Are you James Richet?” he snapped.

The elegant young man inclined his glossy head.

“At your service.”

“Lead me to Abbot Donegal. I am expected.”

Richet perceptibly hesitated; whereupon, plunging his hand with an irritable, nervous movement into some pocket beneath the leather topcoat, the visitor produced a card and handed it to Richet. One glance he gave at it, bowed again in a manner that was almost Oriental and indicated the open gate of an elevator.

A few moments later:

“Federal Agent 56,” Richet announced in his silky tones.

The visitor entered a softly lighted study, the view from its windows indicating that it was situated at the very top of the tall tower. From a chair beside a book-laden desk the sole occupant of the room—who had apparently been staring out at the wintry prospect far below—stood up, turned. Mr. Richet, making his queer bow, retired and closed the door.

Federal Agent 56 unceremoniously cast his wet topcoat upon the floor, dropping his hat on top of it. He was now revealed as a tall, lean man, dressed in a tweed suit which had seen long service. He advanced with outstretched hand to meet the occupant of the study—a slightly built priest, with the keen, ascetic features sometimes met with in men from the south of Ireland and thick, graying hair; a man normally actuated by a healthy sense of humor, but tonight with an oddly haunted expression in his clear eyes.

“Thank God, Father, I see you well.”

“Thank God, indeed.” He glanced at the card which Richet had laid upon his desk even as he grasped the extended hand. “I am naturally prepared for interference with my work, but this thing…”

The newcomer, still holding the priest’s hand, stared fixedly, searchingly, into his eyes.

“You don’t know it all,” he said rapidly.

“This imprisonment—”

“A necessity, believe me. I have covered seven hundred miles by air since you broke off in the middle of your radio address this evening.”

He turned abruptly and began to pace up and down that book-lined room with its sacred pictures and ornaments, these seeming strangely at variance with the large and orderly office below. Pulling a very charred briar pipe from the pocket of his tweed jacket he began to load it from a pouch at least as venerable as the pipe. The Abbot Donegal dropped back into his chair, running his fingers through his hair, and:

“There is one favor I would ask,” he said, “before we proceed any further. It is difficult to talk to an anonymous man.”

He stared down at the card upon his desk. This card bore the printed words:

FEDERAL AGENT 56

but across the bottom right-hand corner was the signature of the President of the United States.

Federal Agent 56 smiled, a quick, revealing smile which lifted a burden of years from the man.

“I agree,” he snapped in his rapid, staccato fashion. “Smith is a not uncommon name. Suppose we say Smith.”

The rising blizzard began to howl round the tower as though many wailing demons clamored for admittance. A veil of snow swept across uncurtained windows, dimming distant lights. Dom Patrick Donegal lighted a cigarette; his hands were not entirely steady.

“If you know what really happened to me tonight, Mr. Smith,” he said, his rich, orator’s voice lowered almost to a murmur, “for heaven’s sake tell me. I have been deluged with telephone messages and telegrams, but in accordance with your instructions—or” (he glanced at the restlessly promenading figure) “should I say orders—I have answered none of them.”

Smith, pipe alight, paused, staring down at the priest.

“You were brought straight back after your collapse?”

“I was. They would have taken me home, but mysterious instructions from Washington resulted in my being brought here. I came to my senses in the small bedroom which adjoins this study.”

“Your last memory being?”

“Of standing before the microphone, my notes in my hand.”

“Quite,” said Smith, beginning to walk up and down again. “Your words, as I recollect them, were: ‘But if the Constitution is to be preserved, if even a hollow shell of Liberty is to remain to us, there is one evil in this country which must be eradicated, torn up by its evil roots, utterly destroyed…’ Then came silence, a confusion of voices, and an announcement that you had been seized with sudden illness. Does your memory, Father, go as far as these words?”

“Not quite,” the priest answered wearily, resting his head upon his hand and making a palpable effort to concentrate. “I began to lose my grip of the situation some time earlier in the address. I experienced most singular sensations. I could not co-ordinate my ideas, and the studio in which I was speaking alternately contracted and enlarged. At one moment the ceiling appeared to become black and to be descending upon me. At another, I thought that I stood in the base of an immeasurably lofty tower.” His voice grew in power as he spoke, his Irish brogue became more pronounced. “Following these dreadful sensations came an overpowering numbness of mind and body. I remember no more.”

“Who attended you?” snapped Smith.

“My own physician, Dr. Reilly.”

“No one but Dr. Reilly, your secretary, Mr. Richet, and I suppose the driver of the car in which you returned, came up here?”

“No one, Mr. Smith. Such, I am given to understand, were the explicit and authoritative orders given a few minutes after the occurrence.”

Smith stopped on the other side of the desk, staring down at the abbot.

“Your manuscript has not been recovered?” he asked slowly.

“I regret to say, no. Definitely, it was left behind in the studio.”

“On the contrary,” snapped Smith angrily, “definitely it was not! The place has been searched from wall to wall by those who know their business. No, Father Abbot, your manuscript is not there. I must know what it contained—and from what source this missing information came to you.”

The ever-rising wind in its fury shook the Tower of the Holy Thorn, shrieking angrily round that lofty room in which two men faced a problem destined in its outcome to affect the whole nation. The priest, a rapid, heavy smoker, lighted another cigarette.

“I cannot make it out,” he said—and now a natural habit of authority began to assert itself in his voice—“I cannot make out why you attach such importance to my notes for this speech, nor why my sudden illness, naturally disturbing to myself, should result in this sensational Federal action. Really, my friend”—he leaned back in his chair, staring up at the tanned, eager face of his visitor—“in effect, I am a prisoner here. This, I may say, is intolerable. I await your explanation, Mr. Smith.”

Smith bent forward, resting nervous brown hands on the priest’s desk and staring intently into those upturned, observant eyes.

“What was the nature of the warning you were about to give to the nation?” he demanded. “What is this evil growth which must be uprooted and destroyed?”

These words produced a marked change in the bearing of the Abbot Donegal. They seemed to bring recognition of something he would willingly have forgotten. Again he ran his fingers through his hair, now almost distractedly.

“God help me,” he said in a very low voice, “I don’t know!”

He suddenly stood up; his glance was wild.

“I cannot remember. My mind is a complete blank upon this subject—upon everything relating to it. I think some lesion must have occurred in my brain. Dr. Reilly, although reticent, holds, I believe, the same opinion.”

“Nothing of the kind,” snapped Smith; “but that manuscript has to be found! There’s life or death in it.”

He ceased speaking abruptly and seemed to be listening to the voice of the storm. Then, ignoring the priest, he suddenly sprang across the room and threw the door wide open.

Mr. Richet stood bowing on the threshold.

CHAPTER TWO

A CHINESE HEAD

In an apartment having a curiously pointed ceiling (one might have imagined it to be situated in the crest of a minaret) a strange figure was seated at a long, narrow table. Light, amber light, came through four near-Gothic windows set so high that only a giant could have looked out of them. The man, whose age might have been anything from sixty to seventy—he had a luxurious growth of snow-white hair—was heavily built, wearing a dilapidated woolen dressing-gown; and his long sensitive fingers were nicotine-stained, since he continuously smoked Egyptian cigarettes. An open tin of these stood near his hand, and he lighted one from the stump of another—smoking, smoking, incessantly smoking. Upon the table before him were seven telephones, one or other of them almost always in action. When two purred into life simultaneously, the smoker would place one to his right ear, the other to his left. He never replied to incoming messages, nor did he make notes.

In the brief intervals he pursued what one might have supposed to be his real calling. Upon a large wooden pedestal was set a block of modeling clay, and beside the pedestal lay implements of the modeler’s art. This singular old man, the amazing frontal development of his splendid skull indicating great mathematical powers, worked patiently upon a life-sized head of an imposing but sinister Chinaman.

In one of those rare intervals he was working delicately upon the high, imperious nose of the clay head, when a muffled bell sounded and the amber light disappeared from the four Gothic windows, plunging the room into complete darkness.

For a moment there was no sound; the tip of a burning cigarette glowed in the darkness. Then a voice spoke, an unforgettable voice, by which gutturals were oddly stressed but every word was given its precise syllabic value.

“Have you a later report,” said this voice, “from Base 8?”

The man at the long table replied, speaking with German intonations.

“The man known as Federal Agent 56 arrived at broadcasting station twenty minutes after midnight. Police still searching there. Report just to hand from Number 38 states that this agent, accompanied by Captain Mark Hepburn, U.S. Army Medical Corps, assigned to Detached Officers List, and a party of nine men arrived Tower of the Holy Thorn at twelve thirty-two, relieving federals already on duty. Agent 56 last reported in conference with Abbot Donegal. The whole area closely covered. No further news in this report.”

“The Number responsible for the manuscript?”

“Has not yet reported.”

“The last report from Numbers covering Weaver’s Farm?”

“Received at 11.07. Dr. Orwin Prescott is still in retirement there. No change has been made in his plans regarding the debate at Carnegie Hall. This report from Number 35.”

The muffled bell rang. Amber light appeared again in the windows; and the sculptor returned lovingly to his task of modeling a Chinaman’s head.

CHAPTER THREE

ABOVE THE BLIZZARD

In Dom Patrick Donegal’s study at the top of the Tower of the Holy Thorn, James Richet faced Federal Officer 56. Some of his silky suavity seemed to have, deserted him.

“I quite understand your—unexpected—appearance, Mr. Richet,” said Smith, staring coldly at the secretary. “You have greatly assisted us. Let me check what you have told me. You believe (the abbot unfortunately having no memory of the episode) that certain material for the latter part of his address was provided early on Saturday morning during a private interview in this room between the Father and Dr. Orwin Prescott?”

“I believe so, although I was not actually present.”

There was something furtive in Richet’s manner; a nervous tremor in his voice.

“Dr. Prescott, as a candidate for the Presidency, no doubt had political reasons for not divulging these facts himself.” Smith turned to Abbot Donegal. “It has always been your custom, Father, to prepare your sermons and speeches in this room, the material being looked up by Mr. Richet?”

“That is so.”

“The situation becomes plainer.” He turned to Richet. “I think we may assume,” he went on, “that the latter part of the address, the part which was never delivered, was in Dom Patrick’s own handwriting. You yourself, I understand, typed out the earlier pages.”

“I did. I have shown you a duplicate.”

“Quite,” snapped Smith; “the final paragraph ends with the words ‘torn up by its evil roots, utterly destroyed.’”

“There was no more. The abbot informed me that he intended to finish the notes later. In fact, he did so. For when I accompanied him to the broadcasting station he said that his notes were complete.”

“And after his—seizure?”

“I returned almost immediately to the studio. But the manuscript was not on the desk.”

“Thank you. That is perfectly clear. We need detain you no longer.”

The secretary, whose forehead glistened with nervous perspiration, went out, closing the door silently behind him. Abbot Donegal looked up almost pathetically at Smith.

“I never thought,” said he, “I should live to find myself so helpless. Can you imagine that I remember nothing whatever of Dr. Prescott’s calling upon me? Except for that vague, awful moment when I faced the microphone and realized that my mental powers were deserting me, I have no recollection of anything that happened for some forty-eight hours before! Yet it seems that Prescott was here and that he gave me vital information. What can it have been? Great heavens”—he stood up, agitatedly—“what can it have been? Do you really believe that I am a victim, not of a failure in my health, but of an attempt to suppress this information?”

“Not an attempt, Father,” snapped Smith, “a success! You are lucky to be alive!”

“But who can have done this thing, and how did he do it?”

“The first question I can answer; the second I might answer if I could recover the missing manuscript. Probably it’s destroyed. We have a thousand-to-one chance. We are indebted to a phone call, which fortunately came through direct to you, for knowledge of Dr. Prescott’s whereabouts.”

“Why do you say ‘which fortunately came through’? You surely have no doubts about Richet?”

“How long with you,” snapped Smith.

“Nearly a year.”

“Nationality?”

“American.”

“I mean pedigree.”

“That I cannot tell you.”

“There’s color somewhere. I can’t place its exact shade. But one thing is clear: Dr. Prescott is in great danger. So are you.”

The abbot arrested Smith’s restless promenade, laying a hand upon his shoulder.

“There is only one other candidate in the running for dictatorship, Mr. Smith—Harvey Bragg. Yet I find it hard to believe that he… You are not accusing Harvey Bragg?”

“Harvey Bragg!” Smith laughed shortly. “Popularly known as Bluebeard, I believe? My dear Dom Patrick, Harvey Bragg is a small pawn in a big game.”

“Yet—he may be President, or Dictator.”

Smith turned, staring in his piercing way into the priest’s eyes.

“He almost certainly will be Dictator!”

Only the mad howling of the blizzard disturbed a silence which fell upon those words—“He almost certainly will be Dictator.”

Then the priest whose burning rhetoric, like that of Peter the Hermit, had roused a nation, found voice; he spoke in very low tones:

“Why do you say he certainly will be Dictator?”

“I said almost certainly. His war-cry ‘America for every man—every man for America’ is flashing like a fiery cross through the country. Do you realize that in office Harvey Bragg has made remarkable promises?”

“He has carried them out! He controls enormous funds.”

“He does! Have you any suspicion, Father, of the source of those funds?”

For one fleeting moment a haunted look came into the abbot’s eyes. A furtive memory had presented itself, only to elude him.

“None,” he replied wearily; “but his following today is greater than mine. Just as a priest and with no personal pretensions, I have tried—God knows I have tried—to keep the people sane and clean. Machinery has made men mad. As machines reach nearer and nearer to the province of miracles, as Science mounts higher and higher—so Man sinks lower and lower. On the day that Machinery reaches up to the stars, Man, spiritually, will have sunk back to the primeval jungle.”

He dropped into his chair.

Smith, resting a lean, nervous hand upon the desk, leaned across it, staring into the speaker’s face.

“Harvey Bragg is a true product of his age,” he said tensely—“and he is backed by one man! I have followed this man from Europe to Asia, from Asia to South America, from South to North. The resources of three European Powers and of the United States have been employed to head that man off. But he is here! In the political disruption of this country he sees his supreme opportunity.”

“His name, Mr. Smith?”

“In your own interests, Father, I suggest it might be better that you don’t know—yet.”

Abbot Donegal challenged the steely eyes, read sincerity there, and nodded.

“I accept your suggestion, Mr. Smith. In the Church we are trained to recognize tacit understandings. You are not a private investigator instructed by the President, nor is Mr. Smith your proper title. But I think we understand one another… And you tell me that this man, whoever he may be, is backing Harvey Bragg?”

“I have only one thing to tell you: Stay up here at the top of your tower until you hear from me!”

“Remain a prisoner?”

Patrick Donegal stood up, suddenly aggressive, truculent.

“A prisoner, yes. I speak, Father, with respect and authority.”

“You may speak, Mr. Smith, with the authority of Congress, of the President in person, but my first duty is to God; my second to the State. I take the eight o’clock Mass in the morning.”

For a moment their glances met and challenged; then:

“There may be times, Father, when you have a duty even higher than this,” said Smith crisply.

“You cannot induce me, my friend, to close my eyes to a plain obligation. I do not doubt your sincerity. I have never met a man more honest or more capable. I cannot doubt my own danger. But in this matter I have made my choice.”

For a moment longer Federal Agent 56 stared at the priest, his lean face very grim. Then, suddenly stooping, he picked up his leather topcoat and his hat from the floor and shot out his hand.

“Good night, Father Abbot,” he snapped. “Don’t ring. I should like to walk down; although that will take some time. Since you refuse my advice, I leave you in good hands.”

“In the hands of God, Mr. Smith, as we all are.”

* * *

Outside on the street, beyond the great bronze door with its figure of the thorn-tortured head, King Blizzard held high revel. Snow was spat into the suffering face when the door was opened, as though powers of evil ruled that night, pouring contumely, contempt, upon the gentle Teacher. Captain Mark Hepburn, U.S.M.C., was standing there. He had one glimpse of the olive face of James Richet, who ushered the visitor out, heard his silky “Good night, Mr. Smith”; then the bronze door was closed, and the wind shrieked in mocking laughter around the Tower of the Holy Thorn.

Dimly through the spate of snow watchful men might be seen.

“Listen, Hepburn,” snapped Smith, “get this address: Weaver’s Farm, Winton, Connecticut. Phone that Dr. Orwin Prescott is not to step outside for one moment until I arrive. Arrange that we get there—fast. Have the place protected. Flying hopeless tonight. Special train to Cleveland. Side anything in our way. Have a plane standing by. Advise the pilot to look up emergency landings within easy radius of Weaver’s Farm. If blizzard continues, arrange for special to run through to Buffalo. Advise Buffalo.”

“Leave it to me.”

“Cover the man James Richet. I want hourly reports sent to headquarters. This priest’s life is valuable. See that he’s protected day and night. Have this place covered from now on. Grab anybody—anybody—that comes out tonight.”

“And where are you going, Chief?”

“I am going to glance over Dom Patrick’s home quarters. Meet me at the station…”

CHAPTER FOUR

MRS. ADAIR

Mark Hepburn drove back through a rising blizzard. The powers of his newly accredited chief, known to him simply as “Federal Agent 56,” were peculiarly impressive.

Arrangements—“by order of Federal Agent 56”—had been made without a hitch. These had included sidetracking the Twentieth Century Limited and the dispatch of an army plane from Dayton to meet the special train.

Dimly he realized that issues greater than the fate of the Presidency were involved. This strange, imperious man, with his irritable, snappy manner, did not come under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Justice; he was not even an American citizen. Yet he was highly empowered by the government. In some way the thing was international. Also, Hepburn liked and respected Federal Agent 56.

And the affection of Mark Hepburn was a thing hard to win. Three generations of Quaker ancestors form a stiff background; and not even a poetic strain which Mark had inherited from a half-Celtic mother could enable him to forget it. His only rebellion—a slender volume of verse in university days, “Green Lilies”—he had lived to repent. Medicine had called him (he was by nature a healer); then army work, with its promise of fresh fields; and now, the Secret Service, where in this crisis he knew he could be of use.

For in the bitter campaign to secure control of the country there had been more than one case of poisoning; and toxicology was Mark Hepburn’s special province. Furthermore, his military experience made him valuable.

Around the Tower of the Holy Thorn the blizzard wrapped itself like a shroud. Only the windows at the very top showed any light. The tortured bronze door remained closed.

Stayton stepped forward out of the white mist as Hepburn sprang from his car.

“Anything to report, Stayton? I have only ten minutes.”

“Not a soul has come out, Captain, and there doesn’t seem to be anybody about in the neighborhood.”

“Good enough. You will be relieved at daylight. Make your own arrangements.”

Hepburn moved off into the storm.

Something in the wild howling of the wind, some message reached him perhaps from those lighted windows at the top of the tower, seemed to be prompting his subconscious mind. He had done his job beyond reproach. Nevertheless, all was not well.

One foot on the running board of the car, he paused staring up to where that high light glimmered through snow. He turned back and walked in the direction of the tower. Almost immediately he was challenged by a watchful agent, was recognized, and passed on. He found himself beside a wall of the building remote from the bronze door. Here there was no exit and he went unchallenged. He stood still, staring about him, his fur coat-collar turned up about his ears, the wind frolicking with his untidy wet black hair.

A slight sound came, only just audible above the shrieking of the blizzard, the opening of a window… He crouched close against the wall.

“All clear. Good luck…”

James Richet!

Then someone dropped, falling lightly in the snow almost beside him. The window closed. Hepburn reached out a long, sinewy arm, grabbed and held his captive… and found himself looking down into the most beautiful eyes he had ever seen!

His prisoner was a girl, little above medium height, but slender, so that she appeared much taller. She was muffled up in a mink coat as a protection against that fierce wind; a Basque beret was crushed down upon curls which reminded him of polished mahogany. A leather satchel hung from one wrist, and she was so terrified that Hepburn could feel her heart beating as he held her in his bear-like grip.

He realized that he was staring dumbly into these uplifted deep-blue eyes, that he was wondering if he had ever seen such long, curling lashes… when duty, duty—that slogan of Quaker ancestors—called to him sharply. He slightly relaxed his hold, but offered no chance of escape.

“I see,” he said, and his dry, rather toneless voice revealed no emotion whatever. “This is interesting. Who are you and where are you going?”

His tones were coldly remorseless. His arm was like a band of steel. Rebellion died and fear grew in the captive. Now she was trembling. But he was forced to admire her courage, for when she replied she looked at him unflinchingly.

“My name is Adair—Mrs. Adair—and I belong to the staff of the Abbot Donegal. I have been working late, and although I know that there’s some absurd order for no one to leave, I simply must go. It’s ridiculous, and I won’t submit to it. I insist upon being allowed to go home.”

“Where is your home?”

“That can be no possible business of yours!” flared the prisoner, her eyes now flashing furiously. “If you like, call the abbot. He will vouch for what I say.”

Mark Hepburn’s square chin protruded from the upturned collar of his coat; his deep-set eyes never faltered in their regard.

“That can come later if necessary,” he said; “but first—”

“But first, I shall freeze to death,” said the girl indignantly.

“But first, what have you got in that satchel?”

“Private papers of Abbot Donegal’s. I am working on them at home.”

“In that case, give them to me.”

“I won’t! You have no right whatever to interfere with me. I have asked you to get in touch with the abbot.”

Without relaxing his grip on his prisoner, Hepburn suddenly snatched the satchel, pulling the loop down over her little gloved hand and thrusting the satchel under his arm.

“I don’t want to be harsh,” he said, “but my job at the moment is more important than yours. This will be returned to you in an hour or less. Lieutenant Johnson will drive you home.”

He began to lead her towards the spot where he knew the Secret Service cars were parked. He had determined to raise a minor hell with the said Lieutenant Johnson for omitting to post a man at this point, for as chief of staff to Federal Agent 56 he was personally responsible. He was by no means sure of himself. The girl embraced by his arm was the first really disturbing element which had ever crashed into his Puritan life; she was too lovely to be real: the teaching of long-ago ancestors prompted that she was an instrument of the devil.

Reluctantly she submitted; for ten, twelve, fifteen paces. Then suddenly resisted, dragging at his arm.

“Please, please, for God’s sake, listen to me!”

He pulled up. They were alone in that blinding blizzard, although ten or twelve men were posted at points around the Tower of the Holy Thorn. A freak of the storm cast an awning of snow from the lighted windows down to the spot upon which they stood, and in that dim reflected light Mark Hepburn saw the bewitching face uplifted to him.

She was smiling; this Mrs. Adair who belonged to Abbot Donegal’s staff; a tremulous, pathetic smile, a smile which in happier hours had been one of exquisite but surely innocent coquetry. Now it told of bravely hidden tears.

Despite all this stoicism, Mark Hepburn’s heart pulsed more rapidly. Some men, he thought, many, maybe, had worshiped those lips, dreamed of that beckoning smile… perhaps lost everything for it.

This woman was a revelation; to Mark Hepburn, a discovery. He was suspicious of the Irish. For this reason he had never wholly believed in the sincerity of Patrick Donegal. And Mrs. Adair was enveloped in that mystical halo which haunts yet protects the Celts. He did not believe in this mysticism, but he was not immune from its insidious charm. He hated hurting her; he found himself thinking of her as a beautiful, helpless moth torn by the wind from some green dell where fairies still hid in the bushes and the four-leaved shamrock grew.

He felt suddenly glad about, and not ashamed of, “Green Lilies.” Mrs. Adair, for one magical moment, had enabled him to recapture that long-lost mood. It was very odd, out there in the blizzard, with his racial distrust of pretty women and of all that belonged to Rome…

It was this last thought—Rome—that steadied him. Here was some black plot against the Constitution…

“I don’t ask you, I entreat you to give me my papers and let me go my own way. I promise, faithfully, if you will tell me where to find you, that I will see you tomorrow and explain anything you want to know.”

Hepburn did not look at her. His Quaker ancestors rallied around him. He squared his grim jaw.

“Lieutenant Johnson will drive you home,” he said coldly, “and will bring you your satchel immediately I am satisfied that its contents are what you say they are.”

* * *

In the amber-lighted room, where the man with that wonderful mathematical brow sat at work upon the bust of a sinister Chinaman, one of the seven telephones buzzed. He laid down the modeling tool with which he had been working and took up the instrument. He listened.

“This is Number 12,” said a woman’s voice, “speaking from Base 8. In accordance with orders I managed to escape from the Tower of the Holy Thorn. Unfortunately I was captured by a federal agent—name unknown—at the moment that I reached the ground. I was taken under escort of a Lieutenant Johnson towards an address which I invented at random. A Z-car was covering me. Heavy snow gave me a chance. I managed to spring out and get to the Z-car. I regret that the federal agent secured the satchel containing the manuscript. There’s nothing more to report. Standing by here awaiting orders.”

The sculptor replaced the receiver and resumed his task. Twice again he was interrupted, listening to a report from California and to another from New York. He made no notes. He never replied. He merely went on with his seemingly endless task; for he was eternally smearing out the work which he had done, now an ear, now a curve of the brow, and patiently remodeling.

A bell rang, the light went out, and in the darkness that unforgettable, guttural voice spoke:

“Give me the latest report of Harvey Bragg’s reception at the Hollywood Bowl.”

“Last report received,” the Teutonic voice replied, and a cigarette glowed in the darkness, “one hour and seventeen minutes ago. Pacific Coast time: twelve minutes after ten. Audience of twenty thousand people, as earlier reported. Harvey Bragg’s slogan, ‘America for every man—every man for America’ was received without enthusiasm. His assurance, hitherto substantiated, that any reputable citizen who is destitute has only to apply to his office to secure immediate employment, went well. Report of end of speech not yet to hand. No other news from Hollywood Bowl. Report sent in by Number 49.”

A moment of silence followed, silence so complete that the crackling of burning tobacco in an Egyptian cigarette might have been heard.

“The report of Number 12,” said the guttural voice, “is overdue.”

“I received a report from Number 12—” he glanced at an electric clock upon the table—“at 2.05 a.m.”

Whereupon, word for word, this man of phenomenal memory repeated the message received from Base 8 exactly as it had been delivered.

A dim bell rang and the room became lighted again. The sculptor picked up a modeling tool.

CHAPTER FIVE

THE SPECIAL TRAIN

The special train bored its way through mists of snow.

“They won’t attempt to wreck us, Hepburn!” Federal Officer 56 smiled grimly and tapped the satchel which had belonged to Mrs. Adair. “This is our safeguard. But there may be an attempt of some other kind.”

In the solitary car Smith sat facing Hepburn. Seven of the party which had taken command of the Tower of the Holy Thorn were distributed in chairs about them. Some smoked and were silent; others talked; others again neither smoked nor talked, but glanced furtively in the direction of Captain Hepburn and his mysterious superior.

“You have done a first-class job, Hepburn” said Smith. “I tricked the man Richet (who is some kind of half-caste) into an admission that this”—he tapped the satchel—“was material supplied by Dr. Prescott.”

“I ordered Richet’s arrest before I left.”

“Good man.”

The train roared through the night and Smith leaned forward, resting his hand upon Hepburn’s shoulder.

“The enemy knows that Dr. Prescott has found out the truth! How Dr. Prescott found out we have got to learn. Clearly he is a brilliant man. I’m afraid, Hepburn—I am afraid—”

He gripped Hepburn’s shoulder and his grip was like that of a vise.

“You have read this thing… and the part which is in Father Donegal’s handwriting tells the story. How he was prevented from broadcasting that story I begin to suspect. Note this particularly, Hepburn: I observed that Dom Patrick, when looking over the typescript brought in by James Richet, moistened the tip of his thumb in turning over the pages. A habit. The point seems significant?”

“Not to me,” Hepburn confessed, staring rather haggardly at the speaker.

“Ah! think it over,” said Smith; then: “I know why you are downcast. You lost the woman—but you got what we were really looking for. Here’s the story of an outside organization aiming to secure control of the country. Don’t worry about Mrs. Adair; it’s only a question of time. We’ll get her.”

Mark Hepburn turned his head aside.

The contents of the satchel had proved to be the completed text of Abbot Donegal’s address, the last five pages in the Father’s untidy manuscript. But those last five pages revealed a plot which, if carried out, would place the United States under the domination of some shadowy being, unnamed, who apparently controlled inexhaustible supplies not only of capital but of men!

Following this revelation, his new chief, “Federal Officer 56,” had given him his entire confidence. He had suspected, but now he knew, that a world drama was being fought out in the United States. A simple soul at heart, he was temporarily dazzled by recognition of the fact that he had been appointed chief of staff in an international crisis to Sir Denis Nayland Smith, Ex-Commissioner of Scotland Yard, created a baronet for his services not only to the British Empire but to the world.

And in a moment of weakness he had let the woman go who might be a link, an irreplaceable link, between their task and this thing which aimed to place the United States under alien domination!

In that hour of disillusionment he felt a double traitor; for this man, Nayland Smith, was so dead straight…

An atmosphere of impending harm hovered over the party. Mark Hepburn was not alone in having seen the venomous blizzard spitting snow unto that bronze Face. Among the seven who accompanied them were members of the ancient faith upheld sturdily by the hand of Abbot Donegal; and these, particularly—touched, he told himself, by medieval superstition—doubted and wondered as they were blindly carried through the stormy night. They were ignorant of what underlay it all, and ignorance breeds fear. They knew that they were merely a bodyguard for Captain Hepburn and Federal Officer 56.

Suddenly, appallingly, brakes were applied, all but throwing the nine men out of their chairs. Nayland Smith came to his feet at a bound, clutching the side of the car.

“Hepburn!” he cried, “go forward with two men. This train can slow down but it must not stop!”

Mark Hepburn ran forward along the car, touching two of the seven on their shoulders as he passed. They followed him out. A flare spluttered through snowy mist, clearly visible from the off-side windows.

“Switch off the lights!” The order came in a high-pitched, irritable voice.

A trainman appeared and the car was plunged in darkness.

A second flare broke through the veil of snow. Federal Officer 56 was crouching by a window looking out, and now:

“Do you see!” he cried, and grabbed the arm of a man who was peering out beside him. “Do you see!”

As the train regained momentum, presumably under the urge of Hepburn, a group of men armed with machine-guns became clearly visible beside the tracks.

The special was whirling through the night again when Hepburn came back. He was smiling his slow smile. Federal Agent 56 turned and stood up.

“This train won’t stop,” said Hepburn, “until we make Cleveland.”

CHAPTER SIX

AT WEAVER’S FARM

“What’s this?” muttered Nayland Smith hoarsely. The car was pulled up. They were in sight of the woods skirting Weaver’s Farm. Night had fallen, and although the violence of the storm had abated there was a great eerie darkness over the snow-covered landscape.

Parties of men carrying torches and hurricane lanterns moved like shadows through the trees!

Smith sprang out on to a faintly discernible track, Mark Hepburn close behind him. They began to run towards the woods, and presently a man who peered about among the silvered bushes turned.

“What has happened?” Smith demanded breathlessly.

The man, whose bearing suggested military training, hesitated, holding a hurricane lamp aloft and staring hard at the speaker. But something in Smith’s authoritative manner brought a change of expression.

“We are federal agents,” said Mark Hepburn. “What’s going on here?”

“Dr. Orwin Prescott has disappeared!”

Nayland Smith clutched Hepburn’s shoulder: Mark could feel how his fingers quivered.

“My God, Hepburn,” he whispered, “we are too late!”

Clenching his fists, he turned and began to race back to the car. Mark Hepburn exchanged a few words with the man to whom they had spoken and then doubled after Nayland Smith.

They had been compelled by the violence of the blizzard to proceed by rail to Buffalo; the military plane had been forced down by heavy snow twenty miles from the landing place selected. At Buffalo they had had further bad news from Lieutenant Johnson.

Crowning the daring getaway of Mrs. Adair, James Richet, whose arrest had been ordered by Mark Hepburn, had vanished…

And now they were plowing a way along the drive which led up to Weaver’s Farm, a white frame house with green shutters, sitting far back from the road! A survival of Colonial New England, it had stood there, outpost of the white man’s progress in days when the red man still hunted the woods and lakes, trading beads for venison and maple sugar. Successive generations had modernized it so that today it was a twentieth-century home equipped from cellar to garret with every possible domestic convenience.

The door was wide open; and in the vestibule, with its old prints and atmosphere of culture, a tall, singularly thin man stood on the mat talking to a little white-haired old lady. He held a very wide-brimmed hat in his hand and constantly stamped snow from his boots. His face was gloomily officious. Members of the domestic staff might dimly be seen peering down from an upper landing. Unrest, fear, reigned in this normally peaceful household.

The white-haired lady started nervously as Mark Hepburn stepped forward.

“I am Captain Hepburn,” he said. “I think you are expecting me. Is this Miss Lakin?”

“I am glad you are here, Captain Hepburn,” said the little lady, with a frightened smile. She held out a small, plump, but delicate hand. “I am Elsie Frayne, Sarah Lakin’s friend and companion.”

“I am afraid,” Hepburn replied, “we come too late. This is Federal Officer Smith. We have met with every kind of obstacle on our way.”

“Miss Frayne,” rapped Smith in his staccato fashion, “I must put a call through immediately. Where is the telephone?”

Miss Frayne, suddenly quite at ease with these strange invaders out of the night, smiled wanly.

“I regret to say, Mr. Smith, that our telephone was cut off some hours ago.”

“Ah!” murmured Smith, and began tugging at the lobe of his left ear, a habit which Hepburn had come to recognize as evidence of intense concentration. “That explains a lot.” He stared about him, his disturbing glance finally focusing upon the face of the thin man.

“Who are you?” he snapped abruptly.

“I’m Deputy Sheriff Black,” was the prompt but gloomy answer. “I have had orders to protect Weaver’s Farm.”

“I know it. They were my orders—and a pretty mess you’ve made of it.”

The local officer bristled indignantly. He resented the irritable peremptory manners of this “G” man; in fact Deputy Sheriff Black had never been in favor of Federal interference with county matters.

“A man can only do his duty, Mr. Smith,” he answered angrily, “and I have done mine. Dr. Prescott slipped out some time after dusk this evening. Nobody saw him go. Nobody knows why he went or where he went. I may add that although I may be responsible, there are federal men on this job as well, and not one of them knows any more than I know.”

“Where is Miss Lakin?”

“Out with a search party down at the lake.”

“Sarah has such courage,” murmured Miss Frayne. “I wouldn’t go outside the house tonight for anything in the world.”

Mark Hepburn turned to her.

“Is there any indication,” he asked, “that Dr. Prescott went that way?”

“Mr. Walsh, a federal agent who arrived here two hours ago, discovered tracks leading in the direction of the lake.”

“John Walsh is our man,” said Hepburn, turning to Smith. “Do you want to make any inquiries here, or shall we head for the lake?”

Nayland Smith was staring abstractedly at Miss Frayne, and now:

“At what time, exactly,” he asked, “was your telephone disconnected?”

“At five minutes after three,” Deputy Sheriff Black’s somber tones interpolated. “There are men at work now trying to trace the break.”

“Who last saw Dr. Prescott?”

“Sarah,” Miss Frayne replied—“that is, so far as we know.”

“Where was he and what was he doing?”

“He was in the library writing letters.”

“Were these letters posted?”

“No, Mr. Smith, they are still on the desk.”

“Was it dark at this time?”

“Yes. Dr. Prescott—he is Miss Lakin’s cousin, you know—had lighted the reading lamp, so Sarah told me.”

“It was alight when I arrived,” growled Deputy Sheriff Black.

“When did you arrive?” Smith asked.

“Twenty minutes after it was suspected Dr. Prescott had left the house.”

“Where were you prior to that time?”

“Out in the road. I had been taking reports from the men on duty.”

“Has anyone touched those letters since they were written?”

“No one, Mr. Smith,” the gentle voice of Miss Frayne replied.

Nayland Smith turned to Deputy Sheriff Black.

“See that no one enters the library,” he snapped, “until I return. I want to look over the room in which Dr. Prescott slept.”

Deputy Sheriff Black nodded tersely and crossed the vestibule.